Introduction

Investigations have shown that floods have immediate, short term and long term psychological effects in adults (Bei et al., 2013; Lamond et al., 2015; Paranjothy et al., 2011). Overall, flood-affected people show the greater frequency of all mental health problems in comparison to non-affected persons (Bei et al., 2013; Paranjothy et al., 2011). Nevertheless, studies have shown that personal income, depth of flooding, move out during reinstatement and alleviating actions are effective issues on the incidence and the prevalence of mental disorders such as stress, anxiety and depression in flood-affected people (Lamond et al., 2015). Since flood victims are often implausible, hopelessness, shocked, stressed and worried at the time of floods (Nasir et al., 2012). Becker et al. (2015) showed that trying to reach a destination is a chief element for aid others in the time of flooding. Thus, take of helping behaviors from volunteered individuals at time of floods is essential to assist the affected people for saving them and their properties. The purpose of this study is to investigate the differential role of social interest and empathy in individuals with and without helping behaviors towards others at the time of flooding in flood-affected áreas.

Prosocial behaviors such as helping and volunteering activities like spending time, money or energy to help others not only make the world better, but also make people feel psychologically better (Lauri, & Calleja, 2019; Li & Xie, 2017; Rini et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2003; Stukas et al., 2016). There is evidence that when individuals assist others, this can endorse some physical and mental benefits for both genders (Rini et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2009). Since self-reported helping behaviors may influence positively people well-being, it was more strongly related to life satisfaction where giving help considers a strong social norm (Oarga et al., 2015). Longitudinal and cross-cultural studies have shown that helping behaviors may produce the greater happiness (Lawton et al., 2020). Thereby, helping should be promoted by public health, education and policy practitioners as a kind of healthy lifestyle, particularly for the social subgroups and ethnic minorities (Yeung et al., 2017). Batson (1987) conceptualised that helping acts as examples of prosocial behaviors at last resulting to the welfare of others.

Altogether, the current theories hypothesised that moral judgment, moral elevation, moral identity and self-efficacy can explain the manifestation of prosocial behaviors in adults. These conceptual models predicted that real-world prosocial behaviors (e.g., helping and volunteering) may provoke moral emotions in individuals when their moral judgment is adequately developed (Ding et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2018). However, Batson (1998, 2010) conceptualised that when people helped others, their motivation was about their self-interest which he called this ‘Universal Egoism'. In a psychoanalytic perspective, Adler (1927) proposed that prosocial behavior equals to social interest. He suggested that this interest in the wellbeing of others and the need to collaborate with others is cultivated in people during childhood by their parents, teachers and significant others. Similarly, Adler (1927) believed that social interest is a tool by which individuals improve their selves and therefore aids them in their egoistic function. However, Weinstein and Ryan (2010) speculated that self-motivation and the voluntary action plays an important role not only in helping others but because the helper believes that this is a virtuous act in itself. Although the potential role of social interest on prosocial behaviors is predictable using the lens of moral judgment, moral elevation, moral identity and self-efficacy (Adler, 1927; Ding et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2018) there is a lack of evidence on how it may influence helping behaviors during natural disasters, particularly in floods.

Moreover, some studies have shown that helping behaviors are linked to empathic concern and an ethical perception of caring for others (Batson et al., 1987; Strelau, 2010; Wilhelm & Bekkers, 2010). Empathy can be considered as an orientation process that reflects a native capability to recognize and be sensitive to the emotive states of others, and it is linked with a motivation to care for their well-being (Decety, 2015). Batson (1991) speculated that such behaviors may be influenced by an individual experiencing another person's emotional state (i.e., empathy) or other-oriented concern (i.e., sympathy). Mehrabian (1997) suggested that emotional empathy is the indirect experience of a person who perceives what the other person feels. Mehrabian (2000) advocated that having empathy can influence healthy and adjusted personality functioning. So, it is a reflection of interactive favorableness and skillfulness. Some people tend to be more empathetic when dealing with others; they commonly have more feelings than others, while others tend to be less empathetic. Different concepts of empathy comprise caring, helping, communication, and interaction between people in an interchange (Davis, 1983; Greenson, 1960; Stotland, 1969; Rogers et al., 1994). Eisenberg and Sadovsky (2004) postulated that helping behaviors can be activated by internalized ethical values as well as by sympathy. They noted that both empathy and sympathy may constrain unkindness and cruelty toward others. From a biological perspective, empathy as a driver motivates some types of prosociality such as helping behaviors which these are part of the natural behavioural selection of many animals (Decety et al., 2016). Banfield and Dovidio (2012) showed that empathic concern may influence the rate of helping responses to natural disasters. Although the potential role of empathy on helping behaviors in natural disasters is rarely examined (Banfield & Dovidio, 2012), there is a dearth of evidence how it may influence helping behaviors in time of flooding.

According to conceptual models and the literature on social interest (Adler, 1927; Batson, 2010, 1998, 1987; Ding et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2018; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010) and empathy (Banfield & Dovidio, 2012; Batson et al., 1987; Decety, 2015; Strelau, 2010; Wilhelm & Bekkers, 2010), this study suggests that these constructs may influence helping behavior towards others in time of flooding. This study is essential on helping behaviors in natural disasters because it explores the potential role of these constructs in relation to helping others. Since there is a gap in evidence in these fields on helping behaviors, this study contributes to better recognize differences between helpers and non-helpers during flooding. The first hypothesis of this study is that helping people would have significantly higher score on social interest than non-helping people during floods. The second hypothesis of this study is that helping people would have significant higher scores on dimensions of empathy than non-helping individuals in time of flooding.

Method

Participants

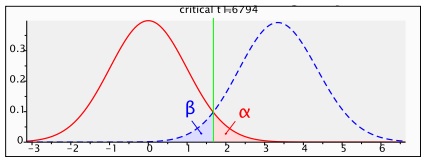

The sample included 180 helping and non-helping adults at the period of flooding (90 people with helping behaviors and 90 persons without helping behaviors) from Ahwaz, Shush, Shadegan, Susangerd, Rofayyeh and AbuHomezeh cities (15 individuals in helping group and 15 individuals in non-helping group from each city), Khuzestan province, Iran. Sample size calculation using G*Power 3.1.9.2 is computed with regard to a difference between two independent groups in this study (Figure 1). This sample size is suitable for comparison between two groups. The actual power analysis was .95 in this study.

All individuals were assigned using a purposive sampling procedure. After obtaining informed consent and the approval by the local IRB, the participants completed a demographic questionnaire and two questionnaires in Persian.

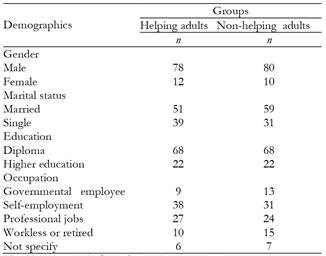

In the group with helping behaviors, the period of help ranged from 5-15 days (N = 34), 16-30 days (N = 47), and 31 -60 days (N = 9). But there were no differences between people who helped according to age in the variables of empathy and social interest. This study included 158 males and 22 females. Also, the distribution of gender was different by groups in this sample. The mean age for the groups with and without a history of helping behaviors were 27.22 (SD= 9.59) and 35.26 (12.04) respectively. The mean age of the total sample were 29.0 (SD= 11.58). Nevertheless, there was a significant age difference between two groups, t (178) =-4.94, p <.01; and non-helping group had higher mean age than helping group. Of the total sample; 100 and 80 individuals lived in rural and urban areas respectively. The level of education in this sample ranged from high school diploma (N = 128) to higher education (N = 52) degrees. Of the total sample, 70 were single and 110 individuals were married. The occupations in this sample involved governmental employee (N = 22), self-employment (N = 69), specialized and professional jobs (N = 51), and workless or retired (N = 25). Nonetheless, 13 individuals did not specify their occupation in the present study. Demographic characteristics for each group are shown in table 1. All participants were Arab ethnic and Muslim.

Instruments

The demographic form involved items on age, gender, the educational level, marital status, occupation, place of residence and the history of helping behaviors. Two questionnaires were applied: (1) the Social Interest Scale (SIS; Crandall, 1975), and (2) the Questionnaire Measure of Empathic Tendency (QMET; Mehrabian & Epestien, 1972).

The Social Interest Scale (SIS; Crandall, 1975). SIS requires individuals to make a number of choices between values that are either relevant or irrelevant to social interest. SIS was developed based on the Adlerian concept of social interest. This measure relates to personality characteristics as well as individual's interests in the welfare of others (Crandall, 1975). The SIS is intended to obtain scores that show either a high level or a low level social interest (i.e. positive or negative relation). According to Watkins (1994), a high score on SIS (positive relation) dimension, is analogous to personality traits including: altruism, volunteerism, and a sense of trustworthiness. On the other end, a low level of Social Interest (negative relation) is related to personality traits including: narcissistic tendencies and hostility. The scale involves the individual to answer by preference one of two response choices for each item that they would select and takes a values approach in looking at social interest (Crandall, 1975). In previous studies, the SIS has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Watkins, 1994). The psychometric properties of SIS have been confirmed in the Iranian population (Ghanbari, 2021; Yaghobi et al., 2016). The reliability of the SIS using Cronbach's alpha internal consistency in this study was .85.

The Questionnaire Measure of Empathic Tendency (QMET; Mehrabian & Epestien, 1972). The QMET is a 33-items unidimensional self-report measure of emotional empathy. The QMET was developed to evaluate emotional empathy, which was defined as indirect or vicarious emotional response to the perceived emotional experiences of others (Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972). Participants report the degree of their agreement or disagreement with each of its 33 items using a 9-point Likert scale (-4 = very strong disagreement to +4 = very strong agreement). The QMET consists of seven subscales: Susceptibility to emotional contagion (SEC; i.e. The people around me have a great influence on my moods), Appreciation of the feelings of unfamiliar and distant others (AFUDO; i.e. Lonely people are probably unfriendly), Extreme emotional responsiveness (ER; i.e. Sometimes the words of a love song can move me deeply), Tendency to be moved by others' positive emotional experiences (TMOPEE; i.e. I like to watch people open presents), Tendency to be moved by others' negative emotional experiences (TMONEE; i.e. Seeing people cry upsets me), Sympathetic tendency (ST; i.e. It is hard for me to see how some things upset people so much), and Willingness to be in contact with others who have problems (WBCOWP; i.e., I would rather be a social worker than work in a job training center). Mehrabian and Epestien (1972) showed that the QMET as a valid measure can differentiate aggression and helping behaviors of people in different social situations. They demonstrated that the QMET is highly reliable and it has good discriminant validity. Many studies supported the psychometric properties of the QMET in different cultures (Archer et al., 1981: Jennifer et al., 2008; Riggioet al., 1989). The validity and reliability of QMET have been verified in the Iranian population (Jahandoost et al., 2020; Manavipor et al., 2021). The reliability of the QMET subscales using Cronbach's alpha internal consistency in this study was .79, .87, .78, .82, .77, .83 and .85 for SEC, AFUDO, ER, TMOPEE, TMONEE, ST and TMONEE respectively. The overall reliability of the QMET using Cronbach's alpha internal consistency in this study was .86.

Procedure

For this ex post facto study on comparison of social interest and empathy in a group of adults with and without helping behaviors at the time of flooding, a purposive sampling method was used (Salkind, 2010). The sample size was considered appropriate for running statistical inferences and comparisons between individuals with or without a history of helping behaviors (Wilson et al., 2007). Initially, national authorities have identified floods in weather-forecasting institutions and crisis centres. Then, helping behaviors are specified with respect an individual non-paid and step forward aids for doing first disaster services and redeemable of flood-affected people at the time of overflowing. These assisting behaviors to flood-affected people include trying to reach them to a safe destination; redeemable their goods and livestock; deliver housing and nourishments for them; and freeing or helping them with removal of floods from homes. The inclusion measures for people in the helping group were (1) being an adult, (2) being a resident of rural and urban areas of Ahwaz, Shush, Shadegan, Susangerd, Rofayyeh and AbuHomezeh cities since over 5 years, (3) had no self-disclosed serious physical disease and mental disorders and this declared by local authorities, (4) have a substantial assisting actions for redeemable of flood-affected people and their possessions at the time of flooding which acknowledged by homegrown authorities and organizations (i.e., Red Crescent and Crisis Administration Staff) and (5) being fluent in the Persian language. Control group members had the same inclusion criteria, except for their non-non-helping behaviors for flood-affected individuals at the time of the floods. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and reviews board approval including respect for individuals, the right to make informed consent for participation in the study, and confidentiality of data for all persons in both groups. All participants, with or without a history of self-help behaviour, were volunteered to participate in the study. Nevertheless, the attendance of a history of helping behaviors in this sample has been acknowledged with respects to their personal archives by local authorities of disaster prevention.

Statistical analysis

IBM's SPSS 22 software was used for data analysis as part of this study. Pearson's correlations, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), and the t-test for independent groups were used in this study. Pearson's correlations coefficient was used to investigate the relationships between social interest and empathy in this study. MANCOVA is used to test whether there are significant differences between the groups in the covariates (i.e. age, gender, marital status, the level of education, and job) on social interest and empathy as dependent variables. The t-test was used to compare social interest and empathy as dependent variables and the helping and the non-helping group as within-subjects or independent variables.

Results

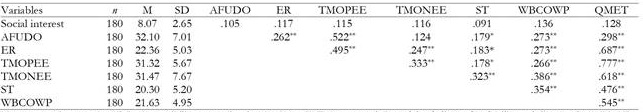

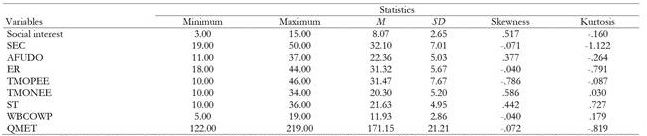

The results showed no incomplete responses and missing values for independent and dependent variables in this sample. The Stem-and-Leaf plot and normal q-q plot of social interest and empathy did not show linear associations between social interest and empathy and outlier data in both variables. In addition, there was no multicollinearity between social interest and empathy constructs in this sample (table 2). The assumptions of normality were satisfactory for the running of MANCOVA (table 3).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables.

Note: *p < .05,

**p < .01,

**SEC= Susceptibility to emotional contagion, AFUDO= Appreciation of the feelings of unfamiliar and distant others, ER= Extreme emotional responsiveness, TMOPEE= Tendency to be moved by others' positive emotional experiences, TMONEE= Tendency to be moved by others' negative emotional experiences, ST= Sympathetic tendency, WBCOWP= Willingness to be in contact with others who have problems, QMET= Questionnaire Measure of Empathic Tendency.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of Dependent Variables.

Note:SEC= Susceptibility to emotional contagion, AFUDO= Appreciation of the feelings of unfamiliar and distant others, ER= Extreme emotional responsiveness, TMOPEE= Tendency to be moved by others' positive emotional experiences, TMONEE= Tendency to be moved by others' negative emotional experiences, ST= Sympathetic tendency, WBCOWP= Willingness to be in contact with others who have problems, QMET= Questionnaire Measure of Empathic Tendency.

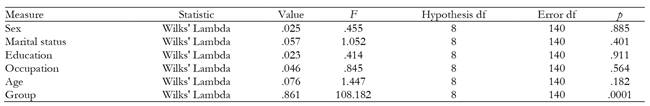

The Wilks' Lambda in MANCOVA demonstrated the role of group status in all dependent variables. However, this analysis rejected the moderating roles of age, gender, marital status, level of education, and occupation in all independent variables (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) for the Statistical Significance of the Independent Variables on the Dependent Variables.

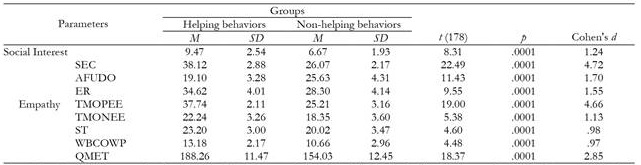

Table 5 shows mean scores and standard deviations for each group in all dependent variables. The results of the t-tests for independent samples indicated significant differences between individuals in helping and non-helping groups in social interest. Also, significant differences were found between individuals in helping and non-helping groups in SEC, AFUDO, ER, TMOPEE, TMONEE, ST, WBCOWP, and the total score of empathy in this study (table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of Social Interest and Empathy in Individuals with and without a History of Helping Behaviors at the Time of Flooding.

Note:SEC = Susceptibility to emotional contagion, AFUDO = Appreciation of the feelings of unfamiliar and distant others, ER = Extreme emotional responsiveness, TMOPEE = Tendency to be moved by others' positive emotional experiences, TMONEE = Tendency to be moved by others' negative emotional experiences, ST = Sympathetic tendency, WBCOWP = Willingness to be in contact with others who have problems, QMET = Questionnaire Measure of Empathic Tendency.

Discussion

With regard to the first hypothesis, individuals with helping behaviors have significantly higher performance in social interest than non-helping people during the flood. These results are in line with the earlier conceptualizations that purported the role of social interest on assisting behaviors to others (Adler, 1927; Batson, 1998, 2010; Ding et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2018; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010). Similarly, prior studies have shown that helping others have advantages for both helpers and the others (Lauri, & Calleja, 2019; Li & Xie, 2017; Rini et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2003; Stukas et al., 2016). Likewise, previous works (Batson, 1987; Lawton et al., 2020; Oarga et al., 2015; Rini et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2009; Yeung et al., 2017), this study revealed that social interest has a significant role on helping others at the time of floods. In reality, social interest can be considered as positive construct that has benefits for individuals and others at the time of natural disasters. Thus, individuals with higher social interest are often prepared to provide unpaid assistance to others during natural disasters. Since the highly social interested people typically are disposed to make key sacrifices toward others at the time of flooding. Altogether, this tendency for social interest and its potential role on helping behaviors may be influenced by socio-cultural context of the person also. Higher social interest may influence people to pursuit for personal mastery and accomplishment by helping others. As Ding et al. (2018), Patrick et al.(2018) and Adler (1927) noted already, this study suggests that moral judgment, moral elevation, moral identity, self-efficacy and social nature of human can explain the potential role of social interest in the amount of helping behaviors in adults. Social interest as a self-motivation positive construct may result in more helping behaviors as a process for personal growth (Batson, 1998, 2010; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010). In individual psychology (Adler, 1927), this study suggests that social interest works as compensation for personal faults during the past life, and as a humanistic behavior for getting the potential help from others in times of natural disaster. However, it seems that social interest is influenced by sociocultural and evolutionary contexts of people with helping behaviors because these functions are often related to the human survival and maintenance of social identity and belongings. In addition, social belonging and altruistic values as sociocultural factors in Khuzestan province had potential roles in demonstrating more social interest among people with helping behaviors at the time of floods. However, social interest and helping behaviors may influence by some social situations such as social modeling and persuasion due to mass media and observation of suffering in food-affected people.

Results from the second hypothesis showed that people in helping group had higher scores on the dimensions of SEC, AFUDO, ER, TMOPEE, TMONEE, ST, WBCOWP and the total score of empathy than individuals in the control group. However, individuals with non-helping history showed a significantly higher performance in AFUDO subscale in comparison to individuals with the history of helping behaviors. Therefore, non-helping individuals are not responsive and sensitive toward the feelings of unfamiliar and distant others, particularly in disasters like floods. These results have shown significant differences in the field of empathy dimensions between helping and non-helping groups at the time of inundating. These results are congruent with former conceptualizations about empathy and caring behaviors (Batson et al., 1987, 1991; Banfield & Dovidio, 2012; Davis, 1983; Eisenberg & Sadovsky, 2004; Greenson, 1960; Mehrabian, 2000, 1997; Rogers et al., 1994; Stotland, 1969; Strelau, 2010; Wilhelm & Bekkers, 2010). In agreement to these conceptual models, thus study indicated that helping persons had the higher empathic tendency in comparison with individuals without helping behaviors at the time of floods. As Decety (2016, 2015) noted already, this study suggesting that empathy as a natural orientation process may predispose some people for doing more helping behaviors. This finding is consistent to an earlier reach that affirmed the role of empathy in helping others at the time of disaster (Banfield & Dovidio, 2012). Overall, this finding displays the interconnection between empathy, caring and kindness about humanistic actions in natural disasters like foods.

According to empathy conceptualizations (Batson et al., 1987; Decety, 2015; Strelau, 2010; Wilhelm & Bekkers, 2010), empathy features may be related to mankind's evolutionary history or they learned moral performance from sociocultural contexts through acculturation from childhood to adulthood. Obviously, some sociocultural concepts like moral reasoning and behavior, ethnic cohesiveness, altruism, mass responsiveness to disasters, defensive mechanisms, personal growth, and life meaning may be useful to understand the possible role of empathy in helping behaviors at the time of floods. Really, local values such as humanity and emotional reflection, religious beliefs, mass media, and common destiny during a natural crisis can motivate people for empathy and helping behaviors at the time of floods. Overall, this study didn't show significant relationships between social interest and empathy in this sample. So, this study suggests that social interest and empathy are different constructs but both have a significant role in helping behaviors at the time of floods.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the role of social interest and empathy on helping behaviors and thus adds on to the existing knowledge on emergency aids during natural disasters such as floods. Natural disaster management organizations and institutions for volunteer groups in crisis may address to social interest and empathy constructs for selection of volunteers at the time of natural disasters like floods. Moreover, community-based mental health programs can use these findings for training purposes among young and adult populations for their readiness for volunteering at the time of natural disasters. However, this study has limitations since it has applied two self-reporting measures in helping and non-helping individuals at the time of flooding. Furthermore, this sample did not reflect the characteristics of helping individuals by gender, the educational level, and ethnicity of the Iranian population. In addition, the distribution of males and females was unequal across groups, and males had a higher proportion than females in this study. Finally, this is an ex post facto design, and did not show the cause-effect relationships between social interest, empathy and helping behaviors at the time of the floods. Additional investigations are critical to understanding the development of social and psychological foundations of social interest and empathy on helping behaviors with regard to gender and cultural differences among adults in natural disasters like floods.