Introduction

COVID-19 has spread worldwide and it has been one of the greatest challenges for societies and countries universally (Bitan et al., 2020). SARS-COV-2 virus has a high infection rate, and COVID-19 contributes to the overload of health care systems and governments (Ferrara & Albano, 2020; Worldometer, 2020). In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic was also associated with a relatively low level of knowledge about the disease, especially in its beginning, and with high uncertainty of its development over time and of its negative consequences on different fronts (e.g., a threat to health, job loss; Bambra et al., 2020; Carlucci et al., 2020; Nicola et al., 2020). Consequently, a sense of fear of the COVID-19 grew among the general population (Fofana et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020). This sense of fear is associated with the virus and the disease in itself (e.g., fear of being near people infected with COVID-19, of getting sick, and of dying), and of not having access to adequate healthcare in case of need due to the overload of healthcare services (Cawcutt et al., 2020; Ferrara & Albano, 2020; Lin, 2020; Okereke et al., 2021).

These concerns resulted in fear of the COVID-19 and are associated with a deterioration of pre-existing mental health conditions (Colizzi et al., 2020). Even in the absence of such conditions, negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and of social isolation on individuals’ mental health are to be expected (Bao et al., 2020; Ornell et al., 2020; Usher, Durkin, et al., 2020; Usher, Jackson, et al., 2020). Although fear may predict behavior changes in the short-term in the direction desired by governmental and health agencies - e.g., physical distancing (Harper et al., 2020) - previous literature has shown that long-term fear has limitative effects and hampers behavioral changes (Adolphs, 2013; Leventhal, 1970; Ropeik, 2004). In the long run, such fear might decrease individuals’ compliance with health behaviors and with (inter)national health agencies' recommendations (Centers for Disease Prevention and Control., 2019; Fofana et al., 2020). Additionally, fear seems also to be associated with the exacerbation of physical and psychological issues. For example, fear weakens the immune system, and is associated with cardiovascular diseases, fatigue, long-term memory impairment, mood swings, among others (Robinson et al., 2013; Roest et al., 2017; Rosenberg, 2017; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004). In recent studies about the effects of COVID-19-related fear, fear of COVID-19 was found to be associated with an increase in reported depression, anxiety, stress, social isolation, loneliness, sleep problems, and cognitive functioning impairment (Baker et al., 2016; Bitan et al., 2020; Bjursell, 2020; Fofana et al., 2020; Koçak et al., 2021; Pyszczynski et al., 2020). It is therefore paramount to monitor fear of COVID-19 over time, in order to study its association with health-related outcomes, health behaviors, and behavioral changes.

Ahorsu and colleagues (2020) have recently developed a measure to assess individuals’ fear of COVID-19: the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S). First, a panel of experts identified and analyzed the content of the items of 28 different measures of fear associated with different stimuli in different study populations. The panel of experts retained 17 items which were sent to a second panel of experts for a second round of content analysis. The 10 items retained after this second round of analysis were piloted on a sample of 46 individuals (Ahorsu et al., 2020), and the three items with low inter-item correlations (r < .06) were eliminated from the final seven-item scale. Exploratory factor analysis suggested a unidimensional reliable (Cronbach's alpha of .82) seven-item scale. The validity of the FCV-19S was furtherly inspected through the analysis of the correlations (positive and moderate) of the total score of this measure with measures of anxiety, depression, and perceived vulnerability to the disease (Ahorsu et al., 2020).

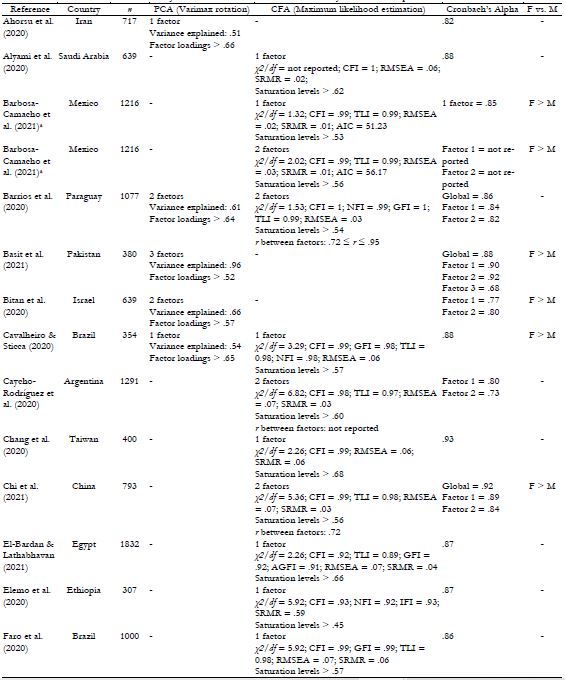

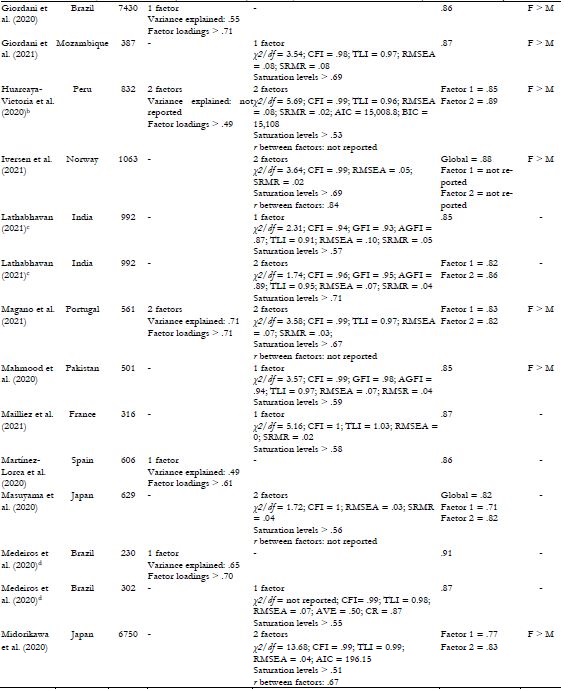

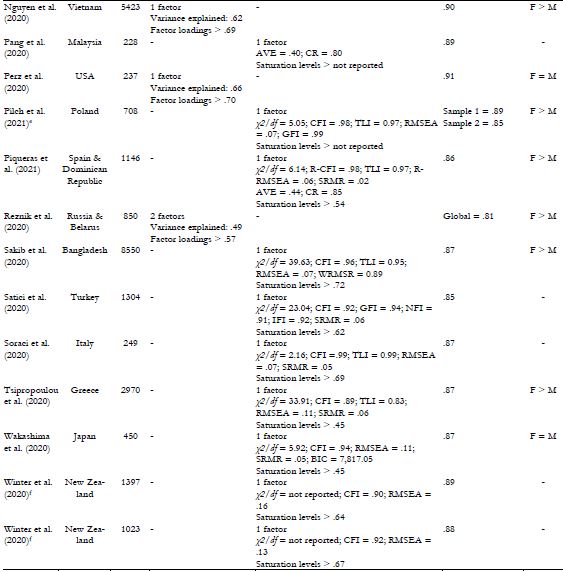

The FCV-19S has been translated, adapted, and validated in 32 countries (see Appendix 1), sometimes more than once, originating a total of 38 different translated versions of this measure (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Alyami et al., 2020; Barbosa-Camacho et al., 2021; Barrios et al., 2020; Bitan et al., 2020; Cavalheiro & Sticca, 2020; Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2020; Chi et al., 2021; El-Bardan & Lathabhavan, 2021; Elemo et al., 2020; Faro et al., 2020; Giordani et al., 2020, 2021; Huarcaya-Victoria et al., 2020; Iversen et al., 2021; Lathabhavan, 2021; Magano et al., 2021; Mahmood et al., 2020; Mailliez et al., 2021; Martínez-Lorca et al., 2020; Masuyama et al., 2020; Medeiros et al., 2021; Midorikawa et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2020; Perz et al., 2020; Pilch et al., 2021; Piqueras et al., 2021; Reznik et al., 2020; Sakib et al., 2020; Satici et al., 2020; Soraci et al., 2020; Tsipropoulou et al., 2020; Winter et al., 2020). The FCV-19S was found to sustain good reliability across several languages and cultures, but debate remains relative to this measure's factorial structure. The validation studies of the American (Perz et al., 2020), Bangladeshi (Sakib et al., 2020), Brazilian (Cavalheiro & Sticca, 2020; Faro et al., 2020; Giordani et al., 2020; Medeiros et al., 2021), Dominican (Piqueras et al., 2021), Egyptian (El-Bardan & Lathabhavan, 2021), Ethiopian (Elemo et al., 2020), French (Mailliez et al., 2021), Greek (Tsipropoulou et al., 2020), Italian (Soraci et al., 2020), Malaya (Pang et al., 2020), Mozambican (Giordani et al., 2021), New Zealand (Winter et al., 2020)), Polish (Pilch et al., 2021), Saudi Arabian (Alyami et al., 2020), Spanish (Martínez-Lorca et al., 2020; Piqueras et al., 2021), Taiwanese (Chang et al., 2020), Turkish (Satici et al., 2020), and Vietnamese (Nguyen et al., 2020) versions of the FCV-19S yielded a one-factor solution, similar to the one found for the original version of this measure. For the Argentinian (Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2020), Belarusian (Reznik et al., 2020), Chinese (Chi et al., 2021), Israeli (Bitan et al., 2020)), Norwegian (Iversen et al., 2021), Paraguayan (Barrios et al., 2020), Peruvian (Huarcaya-Victoria et al., 2020), and Russian versions (Reznik et al., 2020), however, a two-factor structure was found. Some validation studies of the FCV-19S within the same country originated mixed results regarding the factorial structure of the scale. For instance, Lathabhavan (2021) evaluated the one- and two-factor structures of the FCV-19S in a sample of 992 participants from India. This author concluded that both the one- and two-factor models showed good psychometric properties. The same scenario happened in a validation study with 1216 Mexican respondents, where both one- and two-factor models had adequate psychometric properties (Barbosa-Camacho et al., 2021). In Japan, three independent studies evaluated the psychometric properties of a Japanese version of the FCV-19S (Masuyama et al., 2020; Midorikawa et al., 2021; Wakashima et al., 2020). Wakashima and colleagues (2020) were able to replicate the one-factor solution of the original scale, while Masuyama and colleagues (2020) and Midorikawa and colleagues (2021) found a two-factor solution to be the better fit for their data. Finally, in Pakistan, one study found a one-factor structure for the FCV-19S (MMahmood et al., 2020), while another study found a three-factor structure (Basit et al., 2021).

A European Portuguese (i.e., Portuguese as spoken in Portugal) version of the FCV-19S has been studied by Magano and colleagues (2021). Though this version has shown good internal consistency in a convenience and snowball sample of adults from the Portuguese general population recruited between September and November of 2020 through the author's study social network website, the authors were not able to replicate the one-factor structure found by Ahorsu and colleagues (2020). The authors performed exploratory factorial analysis (n = 561), followed by confirmatory factorial analysis (n= 561) testing the measurement model found in the exploratory factor analysis. Their findings yielded and confirmed a two-factor solution for this version of the FCV-19S.

While translated and validated measures in different languages and cultures are necessary to enable the comparison of data from several subjects from different backgrounds - facilitating cross-cultural research and cross-country comparisons - valid cross-country/cultural and cross-group comparisons require at least a minimum form of measurement invariance, i.e. the extent to which the psychometric properties of a given questionnaire generalize across groups (Brown, 2006; Gregorich, 2006; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). The starting point for measurement invariance is configural invariance, i.e. the factor structure of a measure is the same in the different groups (Gregorich, 2006; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Although a measure's factor structure alone in different groups does not provide evidence of configural invariance, equal factor structures are a prerequisite for configural invariance and for testing configural invariance. Additionally, loadings’ pattern must be similar (Byrne, 2016). Attempting to replicate the factorial structure of the original version of the FCV-19S is a first step in verifying this prerequisite to further test stronger forms of invariance (i.e., metric, scalar, and residual/uniqueness invariance), which are necessary for cross-country comparisons. The factor structure variability observed in the different translated versions of the FCV-19S may be associated with the self-report nature of the measure, its inherent subjectivity, the influence of eventual minor psycholexical (as well as of contextual and cultural) inequivalences between the translated versions regarding items’ interpretation (Beaton et al., 2000; Kim & Zabelina, 2015; Solano-Flores & Nelson-Barber, 2001; Suzuki & Ponterotto, 2008).

The purpose of this study is to assess the psychometric properties of a European Portuguese version of the FCV-19S (FCV-19S-P; see Appendix 2) in a sample of Portuguese adults, testing if a one-factor solution - similar to the factorial structure found for the original version of the FCV-19S - would be supported in Portuguese adults from the general population. A secondary aim of the study was to test the multigroup (female vs. male participants) measurement invariance of the FCV-19S-P. We anticipate that: (a) confirmatory factor analysis will support a one-factor solution; (b) internal consistency and composite reliability will range between .73 and .93; (c) the FCV-19S total score will be positively moderately associated with depression, anxiety, and stress; and that (d) female participants will report significantly higher levels of self-reported fear of COVID-19 than their male counterparts. We also anticipate that the FCV-19S-P will show multigroup measurement invariance, allowing for meaningful comparisons between Portuguese female vs. male adult individuals.

Methods

Participants

Participants were adults from the general population living in Portugal between November 2020 and January 2021. Inclusion criteria were: (a) being at least 18 years old; (b) living in Portugal at the time of assessment; (c) being able to read and understand Portuguese; and (d) being willing to participate.

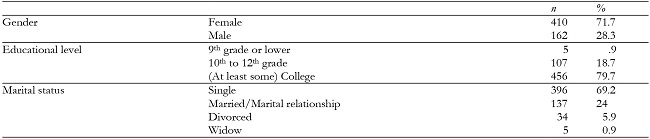

The minimum sample size required to perform the confirmatory factor analysis using structural equation modeling was determined using a priori power calculation, as described below (Cohen, 1988; Soper, 2018). This analysis resulted in a minimum sample size recommended of 400 participants. A total of 580 individuals agreed to participate. Participants with missing values (n = 6.1%) were excluded from the study sample, resulting in a sample of 574 participants. Another two participants, who were found to be multivariate outliers for the FCV-19S-P items, were also excluded from the study sample, resulting in a final sample of 572 individuals (response rate of 99%). Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the study sample. Most participants were women (n = 410, 72 %), aged between 18 and 88 years old (M = 33.46; SD = 13.44). Most participants had a college degree (n = 456, 80 %) and were single (n = 396, 69 %).

Measures

Participants provided basic sociodemographic information (e.g., age, self-identifiedgender, marital status, level of education). Additionally, participants completed the Portuguese version of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale - Short Form (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004) and a Portuguese version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S; Ahorsu et al., 2020).

Fear of COVID-19 Scale.- The FCV-19S (Ahorsu et al., 2020) is a self-report measure aimed at assessing the fear of COVID-19. It is a seven-item scale and participants are requested to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”). The total score ranges between 7 and 35, with a higher sum score indicating higher fear of COVID-19.

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale - Short Form.- The DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) is a three-dimensional self-report measure of anxiety, depression, and stress. It is composed by 21 items grouped in three subscales of seven items each: (a) Depression; (b) Anxiety; and (c) Stress. Participants are asked to respond using a four-item type of Likert scale ranging from 1 (“did not apply to me at all”) to 4 (“applied to me very much”). Both the original (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) and the Portuguese version (Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004) of the DASS-21 showed acceptable to excellent internal consistency (.84 < α < .91 and .74 < α < .85, respectively). This measure has shown good to excellent internal consistency (.86 < α < .91) in the study's sample.

Procedure

The study was reviewed and approved by Ispa's Ethical Committee for Research (reference I/033/04/2020). Permission was obtained from the authors of the original version of the FCV-19S to translate and study the psychometric properties of the measure in a sample of Portuguese adults. The initial phase of the study consisted of translating and back-translating the instructions and items of the FCV-19S. A consensus version was achieved via expert discussion who analyzed the content of the items to certify that the consensus version measured the same construct as the original version. The study data were collected via an online survey platform between November 2020 and January 2021. Prospective participants were invited to participate through multiple channels: (a) website and newsletter of the Order of Portuguese Psychologists - OPP; (b) a circular email sent to organizations (e.g., educational and health institutions and their professionals) and individuals, who were asked to disclose the study to their collaborators, and professional and personal contacts; and (c) social media. Potentially interested individuals were redirected to the study website and online survey, including an informed consent form with a full description of the study aims and procedures. Participants were assured that participation was anonymous and voluntary, and that they could drop out at any time. Upon providing informed consent, participants were invited to complete the study measures.

Data Analysis

The analysis of the psychometric properties of the FCV-19S was based on classical test theory (CTT) analysis, which included confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), average variance extracted, internal consistency, composite reliability, corrected item-total correlation, and assessment of this measure's correlation pattern with criterion measures (DeVellis, 2006). We determined the minimum sample size required to perform the confirmatory factor analysis using an online a priori power calculator (Soper, 2018), considering an effect size (d de Cohen) of 0.30, a significance level of .05, and a power of 0.80 (Cohen, 1988).

We first computed frequencies, means, standard deviations of the study variables with descriptive purposes. Second, skewness (Sk) and kurtosis (Ku) analysis was performed to evaluate items’ sensitivity, with absolute values lower than three and 10, respectively, standing for absence of severe violation of normality assumption and item sensitivity (Byrne, 2016; Kline, 2000). Third, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the one-factor solution of the FCV-19S-P. Model fit was assessed considering χ2 and its subsequent ratio with degrees of freedom (χ2 /df), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Model fit was considered acceptable or good, respectively, in the event that χ2 /df was lower than 5 or 2 (Wheaton, 1987), CFI was higher than .80 and .90 (Bentler, 1990), RMSEA was, lower than .08 or .05 (Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003), and SRMR was lower than .10 or .05 (Hoyle, 1995; Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003). According to Barbara Byrne's recommendations (Byrne, 2016), the model's adjustment was performed step-by-step, through the analysis of correlation among errors, analyzing Modification Indexes (MI) higher than 4 (p < .001; Arbuckle, 2008). The χ2 difference test [Δχ2 (df), p-value], expected cross-validation index (MECVI) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) were computed to compare fit of the initial and final models after adjustments. Statistically significant χ2 statistic and lower MECVI and AIC reflect better fit (Bentler, 1990; Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003). Forth, the convergency of the scale was assessed through the analysis of the average variance extracted (AVE), i.e. the analysis of the amount of variance captured by the latent factor or construct in comparison to the amount of variance that may be caused by measurement error (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). An AVE higher than .50 indicates that the variance explained by the factor or construct is higher than the variance from measurement error (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2009), and convergence is deemed adequate. Fifth, we assessed the reliability of the FCV-19S-P by computing its’ internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha), McDonald's coefficient omega, and composite reliability (CR; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2009): McDonald, 1999), with coefficients higher than .70 and .80 indicating acceptable to good reliability, respectively. Inter-item correlations and corrected item-total correlations were also computed, with acceptable correlations ranging between .30 and .70 (Ferketich, 1991). We then analyzed the pattern of associations between the FCV-19S-P and criterion variables (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress subscales of the DASS-21) by computing the respective Pearson correlation coefficients. Correlation coefficients were considered to be weak, moderate, and strong if absolute values ranged between .10 to .29, .30 to .49, or were higher than .50, respectively (Cohen, 1988). An independent sample t test was performed to assess potentially existing statistically significant gender differences in self-reported fear of COVID-19. Finally, we assessed FCV-19S-P multigroup (female vs. male participants) measurement invariance. To do so, CFA with maximum likelihood estimation was used. In step one, CFA was used to identify the baseline structure of the FCV-19S-P that best fitted participants of both genders Byrne, 2016). In step two, each group best fitting models were incorporated into two multigroup CFA models to test between-group measurement invariance (Byrne, 2004, 2016; Gregorich, 2006; Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). Four nested models were consecutively tested (Byrne, 2016,2004, 2016; Gregorich, 2006; Schmitt and Kuljanin, 2008) to assess: (a) configural invariance (no equality constrains were imposed on parameters; it implies that the factor structure of the FCV-19S-P is the same in the two groups); (b) metric invariance (factor loadings were constrained; common factors have similar meaning across groups); (c) scalar invariance (factor loadings and item intercepts were constrained; the latent factors’ scores are similar in both groups); and (d) residual/uniqueness invariance (factor loadings, item intercepts and item residual variances were constrained; the item intercepts and residual invariances are similar across the two groups). Forms of measurement invariance that are subsequent to configural invariance are confirmed by comparing the fit of the subsequent nested model with the one of the preceding nested models, in which similar fit suggests a subsequent form of measurement invariance. To test the relative fit of nested models we computed the difference between alternative fit indices for nested models: χ2/df, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR, with p < .05 for Δ χ2/df, a decrease in CFI of ≥ .01 complemented by an increase in RMSEA of ≥ .015 among nested invariance models indicating a significant worsening of fit (D. C. R. Chen et al., 2012; F. F. Chen, 2007; Meade et al., 2008). For the SRMR fit indices, an increase of ≥ .03 in the configural model and an increase of ≥ .01 in the following models would indicate a significant worsening of fit (F. F. Chen, 2007). Statistical analyses were executed using software IBM SPSS Statistics (v. 26) and AMOS statistical package (v. 26). Alpha was set at .05 for all statistical analyses.

Results

Descriptive Information

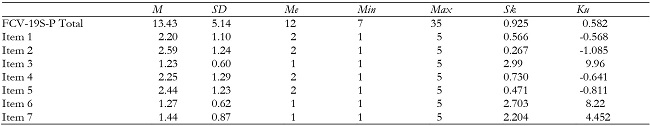

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. As can be seen, the fear of COVID-19 ranged between 7 and 35 (M = 13.4, SD = 5.1). Answers to individual items ranged between one and five, with average scores ranging between 1.2 (SD = 0.6 for item 3 and 2.6 (SD = 1.2) for item 2. The entire five-point Likert scale was used by participants for all items, and the distribution of all items had acceptable skewness (0.267 < S k < 2.99) and kurtosis (−0.568 < Ku < 9.96) values.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Convergence of the FCV-19S-P

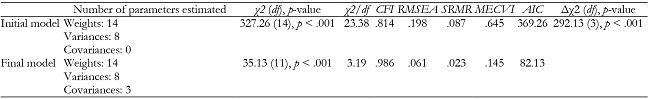

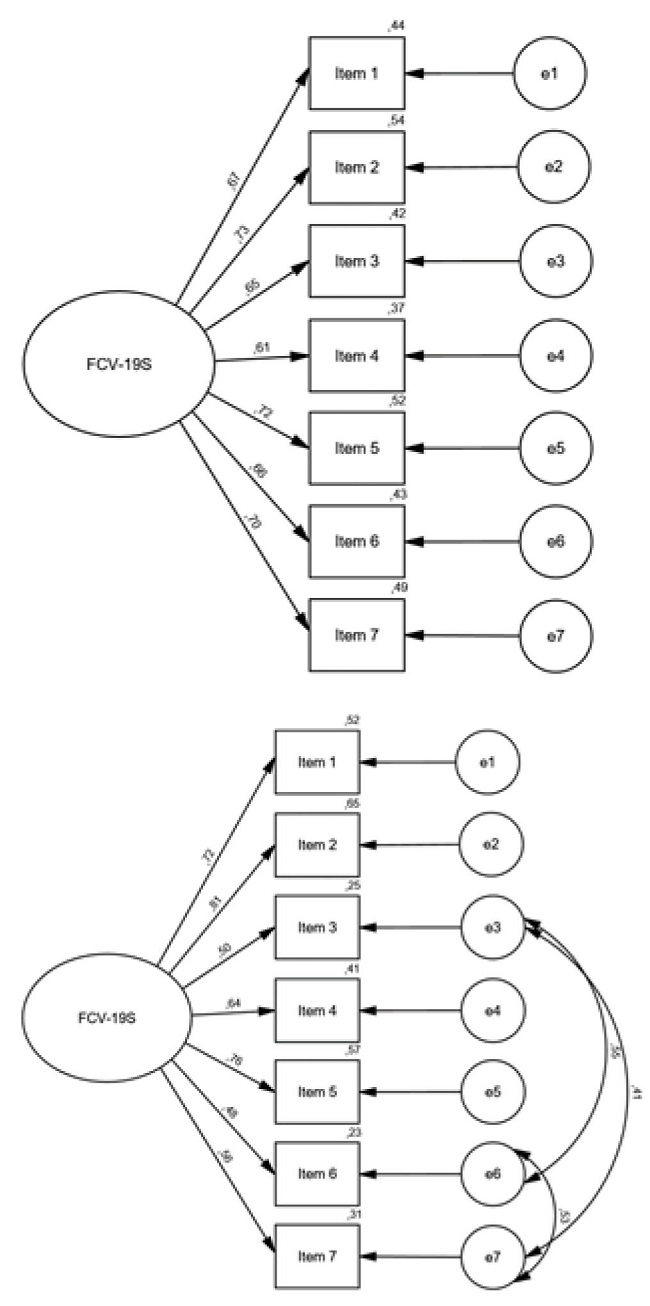

The model fit indexes for CFA are presented in Table 3, while Figure 1 shows the standardized factorial weights and individual items' reliability for the initial and final models. Only two out of four combined fit indices for the CFA supported the one-factor solution with acceptable fit (χ2 /df = 23.38; CFI = .81; RMSEA = .20; SRMR = .09). Thus, the quality of fitness of the initial model was limited. The inspection of the FCV-19S-P items suggests that some of them might have similar content. This may be a possible explanation for the limited fitness of the unidimensional solution on this sample. For instance, items three (“My hands become clammy when I think about coronavirus-19”), six (“I cannot sleep because I’m worrying about getting coronavirus-19”), and seven (“My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting coronavirus-19”), all seem to assess psychosomatic manifestations of fear. The analysis of the modification indices seems to suggest that the error terms of these three items should be correlated. These error terms were correlated sequentially resulting in a modified one-factor model that maintained the seven items of the original FCV-19S-P.

The four combined fit indices suggested acceptable to good fit of this modified model (χ2 /df = 3.19; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .02). This model showed a higher goodness of fit than the initial model [Δχ2 (3) = 292.13, p < .001; MECVI: .15 vs. .65; AIC: 82.13 vs. 369.26). Six of the items (86%) showed loadings equal or higher than .50, with item six presenting a loading of .48, indicating that the corresponding latent dimensions explained, at least, 25% of the result of all items except for item six. FCV-19S-P's AVE was estimated in .42, indicating a less than optimal convergence of this measure.

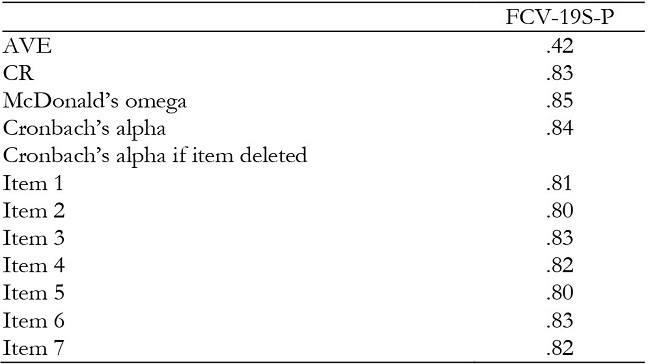

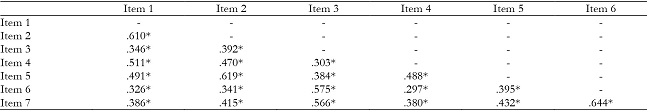

Reliability: Internal Consistency and Composite Reliability

Table 4 summarizes the results for the measure's reliability (see Appendix 3 for inter item-correlations). As can be seen, the overall scale showed a good internal consistency (α = .84), coefficient omega (ω = .85), and composite reliability (CR = .84), with internal consistency coefficients if single items are deleted being comparable to the overall Cronbach's alpha, indicating that no item detracts from the reliability of the FCV-19S-P (see Table 4). Inter-item correlation coefficients ranged from .30 to .62 and maybe considered significant and not redundant.

Association of FCV-19S-P with Gender, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

Fear of COVID-19 presented weak to moderate positive and statistically significant associations with scores of depression (r = .23, p < .001), anxiety (r = .25, p < .001) and stress (r = .31, p < .001), as measured by the Portuguese version of DASS-21. There was a statistically significant gender difference on average fear of COVID-19, t(570) = 6.056, p < .001, d = 4.98, with women (M = 14.22, SD = 5.17) reporting greater fear of COVID-19 than their male counterparts (M = 11.42, SD = 4.47).

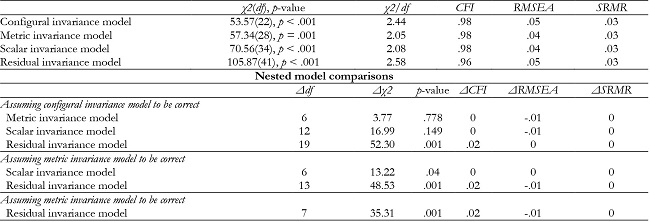

Multigroup Measurement Invariance of the FCV-19S-P

The model fit of the four nested models and the fit indices for the multigroup measurement invariance models (female vs. male participants) are presented in Table 5. The configural model showed acceptable (χ2/df = 2.44) to good fit (CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05, and SRMR = .03) in all fit indices. It was, therefore, considered suitable to be used as the basis for testing the constrained models.

In comparison to the unconstrained model, the metric invariance model presented no significant worsening of the model fit in all four fit indices [Δχ2 (df) = 3.77, Δdf = 6, p = .778; ΔCFI = 0; ΔRMSEA = -.01; ΔSRMR = 0], which suggests that the magnitudes of factor loadings were similar across groups. Similarly, the scalar invariance model revealed no significant deterioration of model fit in three out of four fit indices [Δχ2 (df) = 13.22, Δdf = 6, p = .04; ΔCFI = 0; ΔRMSEA = 0; ΔSRMR = 0], suggesting that item intercepts are similar across groups. The residual invariance model, however, resulted in a slight, but significant, worsening of model fit in two out of four fit indices comparing to the metric and to the scalar invariance models [Δχ2 (df) = 35.31, Δdf = 7, p < .001; ΔCFI = .02; ΔRMSEA = -.01; ΔSRMR = 0], suggesting that item residual variances were not similar across groups.

The partial residual invariance was tested (i.e. to find the source of non-invariance in the residual invariance model). We implemented a backward method involving sequentially dropping the constrains that contributed greater chi-square valued to the model. As a result, we sequentially freed items 3, 6, and 7, so that the partial residual invariance model had no significant worsening in model fit as compared with the scalar invariance model for all fit indices [Δχ2 (df) = 5.64, Δdf = 4, p = .228; ΔCFI = 0; ΔRMSEA = 0; ΔSRMR = 0]. This resulted in a partial residual invariance model with good fit (χ2 /df = 2.01; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .03].

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic had a severe negative psychological and socioeconomic impact on societies and individuals (Bitan et al., 2020). Its rapid spread, the initial lack of knowledge in regards to how it is transmitted and its short/long-term effects, and the uncertainty relative to how would the pandemic unfold in the medium/long-term, nurtured a generalized fear of the COVID-19 (Bambra et al., 2020; Carlucci et al., 2020; Nicola et al., 2020). Such fear seems to be associated with an aggravation of the pandemic's negative impact upon individuals’ psychological and physical health, social support, and health behaviors (Bao et al., 2020; Ornell et al., 2020; Usher, Durkin, et al., 2020; Usher, Jackson, et al., 2020). Given the potentially noxious effect of fear of COVID-19, Ahorsu and colleagues (2020) have developed the FCV-19S. Their purpose was to provide a useful tool to monitor the fear of COVID-19 and its consequences. The FCV-19S has now been translated into various languages and studied in samples of adults in 32 different countries.

The current study aimed at assessing the psychometric properties of a European Portuguese version of the FCV-19S, testing if a one-factor solution, similar to the one found for the original version of the FCV-19S, would be yielded in Portuguese adults from the general population. A secondary aim of the study was to test the multigroup (female vs. male participants) measurement invariance of the FCV-19S-P. The study findings supported most of our results’ expectations. First, as predicted, confirmatory factor analysis supported the unidimensional factor structure of seven items of the FCV-19S-P, similar to the factorial structure found for the original version of FCV-19S (Ahorsu et al., 2020). Second, as expected, the FCV-19S-P showed a good reliability on the range of the coefficients found in previous research studies examining the psychometric properties of other versions of the FCV-19S (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Alyami et al., 2020; Barbosa-Camacho et al., 2021; Barrios et al., 2020; Bitan et al., 2020; Cavalheiro & Sticca, 2020; Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2020; Chi et al., 2021; El-Bardan & Lathabhavan, 2021; Elemo et al., 2020; Faro et al., 2020; Giordani et al., 2020, 2021; Huarcaya-Victoria et al., 2020; Iversen et al., 2021; Lathabhavan, 2021; Magano et al., 2021; Mahmood et al., 2020; Mailliez et al., 2021; Martínez-Lorca et al., 2020; Masuyama et al., 2020; Medeiros et al., 2021; Midorikawa et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2020; Perz et al., 2020; Pilch et al., 2021; Piqueras et al., 2021; Reznik et al., 2020; Sakib et al., 2020; Satici et al., 2020; Soraci et al., 2020; Tsipropoulou et al., 2020; Winter et al., 2020). Third, fear of COVID-19, as measured by the FCV-19S-P, was positively correlated with measures of depression, anxiety and stress (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Bitan et al., 2020; Satici et al., 2020), as anticipated. Forth, congruent with our expectations and with the findings from previous studies examining the psychometric properties of the FCV-19S, women reported greater fear of COVID-19 than men (Barbosa-Camacho et al., 2021; Basit et al., 2021; Bitan et al., 2020; Cavalheiro & Sticca, 2020; Chi et al., 2021; Giordani et al., 2021, Giordani et al., 2021; Huarcaya-Victoria et al., 2020; Iversen et al., 2021; Magano et al., 2021; Mahmood et al., 2020; Midorikawa et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2020; Pilch et al., 2021; Piqueras et al., 2021; Reznik et al., 2020; Sakib et al., 2020; Tsipropoulou et al., 2020). Finally, the FCV-19S-P multigroup (female vs. male participants) scalar (and residual) invariance was (at least partially) supported. However, our findings provide only partial support for the convergency of the FCV-19S-P. In fact, the average variance extracted (AVE) lower than the proposed cut-off point seems to suggest that the variance associated with measurement error may be slightly higher than the one captured by the construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Nonetheless, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981), given the measure's good reliability, as assessed through Cronbach's alpha, McDonald's omega, and composite reliability coefficients, convergency of the construct may still be considered adequate. Taken together, these findings seem to suggest that the FCV-19S-P is a reliable and valid measure of fear of COVID-19, that may be used in studies focusing on Portuguese adults from the general population, and to draw valid conclusions on between-gender comparisons.

Our results are consistent with those found in the validation study of the original version of the FCV-19S (Ahorsu et al., 2020), as well as with those found in other 25 (out of 38) translated versions of this measure (Alyami et al., 2020; Barbosa-Camacho et al., 2021; Cavalheiro & Sticca, 2020; Chang et al., 2020; El-Bardan & Lathabhavan, 2021; Elemo et al., 2020; Faro et al., 2020; Giordani et al., 2020, 2021; Lathabhavan, 2021; Mahmood et al., 2020; Mailliez et al., 2021; Martínez-Lorca et al., 2020; Medeiros et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2020; Perz et al., 2020; Pilch et al., 2021; Piqueras et al., 2021; Sakib et al., 2020; Satici et al., 2020; Soraci et al., 2020; Tsipropoulou et al., 2020; Wakashima et al., 2020; Winter et al., 2020). They differ, however, from the results found in 12 other versions (Barbosa-Camacho et al., 2021; Barrios et al., 2020; Basit et al., 2021; Bitan et al., 2020; Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2020; Chi et al., 2021; Huarcaya-Victoria et al., 2020; Iversen et al., 2021; Lathabhavan, 2021; Masuyama et al., 2020; Midorikawa et al., 2021; Reznik et al., 2020) in regards to the factorial structure of the measure. Our results are also inconsistent with those found for the European Portuguese version of the FCV-19S proposed by Magano and colleagues (2021), with respect to the factorial structure of the two versions and to their multigroup measurement invariance. One possible explanation for the factorial differences between our version and Magano and colleagues’ (2021) version might be the existence of slight translation nuances which may originate a slightly different interpretation of the items by adults from the general population living in Portugal. The confirmation of the one-factor solution, as found for the FCV-19S-P version we developed and studied here - unlike the version of Magano and colleagues (2021) - is a first step for testing configural invariance relative to the original version and other 25 translated versions, as a single-sample confirmatory factor analysis replicating a previously supported measurement model is a precondition for further testing configural invariance (Byrne, 2016). This minimum form of measurement invariance, yet not strictly sufficient, constitutes a pre-requisite for defensible comparisons relative to results obtained with samples of participants from different cultures, languages, and countries (Gregorich, 2006; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Further cross-cultural research comparing different versions of the FCV-19S and examining measurement invariance is necessary to confirm that valid conclusions on cross-cultural/country comparisons may be drawn.

Unlike Magano and colleagues’ (2021) version, the FCV-19S-P showed full configural, metric, and scalar invariance, suggesting that both genders perceive items and the underlying construct similarly. This suggests that gender comparisons relative to the estimated factor variances and covariances, and to the observed means of fear of COVID-19 are defensible. Though only partial residual invariance was supported by our findings, some authors argue that this type of invariance has limited practical value (Gregorich, 2006) and is thus not mandatory for multigroup comparisons. As a result, valid conclusions regarding meaningful gender comparisons relative to groups' estimated (co)variances and estimated/observed means could potentially be drawn. In our sample, women reported higher fear of COVID-19, a result that may be associated with a greater sensitivity/vulnerability to stress and anxiety of women (McLean & Anderson, 2009; Olatunji et al., 2005; Tolin & Foa, 2008).

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations that need to be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Ours was a convenience sample, composed mostly of young highly educated adults, and women. In addition, we used a web-delivered administration method of the study measures, which may have resulted in a participant selection bias. Thus, the study sample is not representative of the Portuguese adult population (INE, 2020), which prevents the generalization of our findings to the study population. Future research with other samples is necessary to examine the reliability and generalizability of these findings. On the other hand, because of the cross-sectional design of this study, it was not possible neither to examine the test-retest reliability of the FCV-19S-P and its sensitivity to change, nor to assess the measure's longitudinal measurement invariance. Thus, future studies with longitudinal design are necessary to verify the longitudinal measurement invariance and the stability over time of the FCV-19S-P. Finally, other measures assessing event-related fear were not administered. This would have helped us to further examine the FCV-19S-P convergency. Further research including alternative measures of fear is warranted.

Conclusions

Despite the study limitations, our findings support the reliability and validity of a one-factor European Portuguese version of the FCV-19S, as well as its multigroup/gender invariance. The FCV-19S-P is a useful tool that might be used to monitor the fear of COVID-19 among Portuguese adults and draw meaningful gender comparisons. Since fear can lead to various mental health disorders and be a potential predictor of vulnerable groups, the assessment of the level of fear among the general population by health entities and professionals can be a powerful ally in preventing mental health disorders and uncovering vulnerable groups (Holmes et al., 2020; Huarcaya-Victoria et al., 2020; Nitschke et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). This would allow for the development of tailored interventions to reduce the fear of COVID-19 and help healthcare providers to identify those most vulnerable individuals at greater risk and that would benefit the most from rapid and timely psychological intervention. Future research should test longitudinal and cross-cultural multigroup measurement invariance to guarantee that the FCV-19S(-P) measures the same construct in the same way across time and populations.