Introduction

Sexting can be broadly defined as the voluntary creation (without the presence of coercion, suggestions, or extortion) and delivery of text messages, images, or videos containing personal sexual content via the internet or mobile devices (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017; Morelli et al., 2016). Nowadays, sexting is considered a new form of interpersonal communication that allows people to maintain sexual interactions, and it has been associated with positive consequences when done willingly (e.g., Drouin et al., 2017; Parker et al., 2013). However, sexting sometimes occurs in a negative context (Englander, 2015), especially when it is done without wanting it. In this sense, unwanted but consensual sexting is compliant sexting behavior that consists of willingly engaging in unwanted sexual behavior via sexually explicit text, pictures, or videos (Drouin & Tobin, 2014). Studies have shown that the prevalence of unwanted sexting (e.g., Drouin et al., 2015; Drouin & Tobin, 2014) can be as high as that of wanted sexting (e.g., Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015; Morelli et al., 2016; Mori et al., 2020).

Although unwanted sexting is an understudied phenomenon, it is evident that it leads to a far greater number of negative consequences than wanted sexting (e.g., higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, and lower self-esteem; Klettke et al., 2019), and it is associated with other forms of sexual victimization, because it can function as an online extension of offline forms of sexual violence (Choi et al., 2016; Cornelius et al., 2020). Thus, the goal of this study was to examine (a) the extent to which wanted and unwanted sexting occurs among young adult women and men, (b) how both types of sexting relate to other forms of sexual violence (sexual coercion and online sexual victimization), and (c) how both types of sexting are related to sexual and life satisfaction.

Online and offline sexual violence and sexting

As mentioned above, sexting has been associated with risky sexual behaviors (see the review by Van Ouytsel et al., 2015). Specifically, several studies have found relationships between sexting and aggressive online and offline behaviors, including online sexual victimization and sexual coercion (e.g., Choi et al., 2016; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015; Ross et al., 2019).

Sexual coercion is unwanted face-to-face sexual contact that occurs after a person is pressured through different tactics (e.g., telling lies, using verbal pressure or threats, showing displeasure, or getting angry; Koss et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2017). For its part, online sexual victimization (OSV) could be considered an extension of offline sexual harassment (e.g., Fest et al., 2019; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015) and is defined as the experience of pressure through the internet or mobile phones to provide unwanted cooperation or sexual contact and/or the distribution by the perpetrator of the victims' sexual images or information against their will (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015). According to this definition, OSV includes behaviors such as sexting coercion, sextortion, and sexpreading. Research on the relationship between offline and online victimization has found an overlap in online and face-to-face aggression (Wright & Li, 2012). For example, Marganski and Melander (2018) showed a relationship between partner cyberaggression victimization and in-person sexual partner violence victimization experiences. Furthermore, Kernsmith et al. (2018) and Walker et al. (2021) demonstrated a positive association between sexual coercion and OSV.

Considering that unwanted but consensual sexual activity has extended to the virtual world (Drouin & Tobin, 2014), it is plausible to assume the existence of a relationship between sexual coercion and sexting. Past research has confirmed this assumption (e.g., Choi et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2019, Wood et al., 2015). For example, Choi et al. (2016) showed in a sample of female adolescents that those who had experienced sexual coercion were more likely to engage in sexting behaviors. Similar results were found for young adults, indicating that experiences of offline sexual coercion were significantly linked to sexting (Wood et al., 2015). Despite this association, to our knowledge, no previous studies have analyzed the relationship between sexual coercion and unwanted but consensual sexting. However, research has consistently found that sexual coercion is related to offline unwanted but consensual sex, with individuals who experience coercion engaging in unwanted sex to a greater extent (e.g., Katz & Tirone, 2010; Ross et al., 2019). Based on these results, we expected to find this association could be extrapolated to online sex.

Regarding the association between online victimization and sexting, some studies have found a positive relationship between sexting and cyberbullying victimization (Quesada et al., 2018; Reyns et al., 2013). Focusing specifically on OSV, the research has indicated that engaging in sexting increased the probability of reporting OSV throughout different samples of adults (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015), emerging adults (Fest et al., 2019), and adolescents (Marengo et al., 2019). Gámez-Guadix and Mateos-Pérez (2019) analyzed the relationship between sexting and OSV in a longitudinal study of adolescents, showing not only that sexting predicted an increase in OSV, but also that OSV was related to increasing participation in sexting 1 year later. Similarly, Wood et al. (2015) found that individuals were more likely to engage in sexting if they had experienced online victimization. Focusing specifically on unwanted sexting, Ross et al. (2019) showed a positive correlation between sexting coercion and unwanted but consensual sexting, so we expected OSV to increase the probability of engaging in such behavior.

Consequences of sexting on sexual and life satisfaction

In an effort to gain a deeper understanding of the consequences of sexting, recent literature has explored how sexting is associated with individuals' well-being, such as their sexual satisfaction and life satisfaction. Regarding sexual satisfaction, the vast majority of studies have found sexting to be a positive predictor of sexual satisfaction in adults (e.g., Brodie et al., 2019; Galovan et al., 2018; Oriza & Hanipaja, 2020). However, all these studies asked about sexting without considering whether it was wanted or unwanted. Although no studies to our knowledge have analyzed the relationship between unwanted but consensual sexting and sexual satisfaction, the literature about unwanted sex has consistently shown that one of the negative consequences of sexual victimization is sexual dissatisfaction (e.g., Katz & Myhr, 2008). Specifically, research on consensual but unwanted sex (e.g., sexual compliance) has demonstrated that individuals who comply with unwanted sex reported decreased sexual satisfaction (e.g., Katz & Tirone, 2009, 2010).

As far as we know, the relationship between sexting and life satisfaction is poorly explained in the literature. Only the study of young adults by Fest et al. (2019) has related wanted sexting to lower life satisfaction through a higher number of OSV experiences. However, there is empirical evidence that sexual satisfaction affects people's overall quality of life (e.g., Davinson et al., 2009), and it is cross-sectionally and longitudinally associated with life satisfaction (e.g., Schmiedeberg et al., 2017; Stephenson & Meston, 2015; Woloski-Wruble et al., 2010), so it is plausible to expect that unwanted sexting would predict negative life satisfaction.

Current study

As shown above, previous studies regarding prevalence of sexting behaviors failed to differentiate between wanted and unwanted but consensual sexting. Therefore, we aimed to expand the knowledge of this phenomenon in Spanish adults by having as the first objective to investigate the prevalence of sexting with a focus on both wanted and unwanted sexting. Additionally, although studies have suggested concurrence between sexting and other forms of violence, the extent of this relationship is not fully understood, because of the absence of literature associating both wanted and unwanted sexting with online and offline sexual violence. Thus, our second objective was to identify specific factors (OSV and sexual coercion) that may influence the probability of engaging in both types of sexting. Finally, to our knowledge, no previous studies have specifically analyzed both wanted and unwanted sexting and their consequences for sexual and life satisfaction so our third objective was to analyze the potential outcomes (sexual and life satisfaction) of such behaviors.

Based on the above objectives, we expected that individuals with experiences of sexual coercion and OSV would be more likely to engage in unwanted sexting, and we did not expect this association with wanted sexting (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, we expected that experiences of sexual coercion and OSV would predict negative sexual and life satisfaction via unwanted sexting behaviors, but not via wanted sexting behaviors (Hypothesis 2). Finally, we expected that higher sexual coercion experiences would predict a higher number of OSV experiences, which would lead to a higher probability of engaging in unwanted sexting and then would result in lower sexual and life satisfaction (Hypothesis 3). Again, we did not expect this association for wanted sexting.

Method

Participants

The initial sample consisted of 344 Spaniards over 18 years of age who volunteered to participate. Of those, 34 participants were excluded from the analysis because they did not complete the full questionnaire. The final sample was composed of 310 participants (Mage = 21.99 years, SD = 3.22, range from 18 to 45), of whom 77.1% were women, 22.6% were men, and 0.3% did not identify as women or men. Of the participants, 58.1% were involved in a romantic relationship, and 41.9% did not have a romantic partner. A sensitive power analysis was conducted using linear multiple regressions: fixed model, R2 deviation from zero in G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) to determine our ability to detect the effect of OSV and sexual coercion on sexting. For our sample (N = 310, α = .05), the sensitivity analysis suggested that effect sizes of ƒ2 = 0.06 were necessary to produce power at the 0.80 level.

Procedure and Design

This research followed a quantitative approach using a non-experimental descriptive study of populations through surveys with cross-sectional probability samples (Montero & León, 2007). Specifically, participants were recruited with a snowball sampling procedure. Undergraduate students at a Spanish university underwent basic training about sampling procedures and then were asked to distribute the online questionnaire among their acquaintances. Specifically, once participants agreed to participate in the study, they were given access to the online survey. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed about the study's purpose, were ensured confidentiality and anonymity, and signed an informed consent form. Then they completed the questionnaire. The study was approved by the corresponding college's Institutional Review Board and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Sexual coercion

The Sexual Coercion in Intimate Relationships Scale (SCIRS; Shackelford & Goetz, 2004) was used. Participants indicated whether they had experienced at some point in their life: commitment manipulation (10 items; e.g., “My partner hinted that if I loved him, I would have sex with him”), defection threat (nine items; e.g., “My partner hinted that he would have sex with another woman if I did not have sex with him”), and resource manipulation or violence (15 items, four of which included threats or the use of physical force; e.g., “My partner threatened to use violence against me if I did not have sex with him”), using a 7-point response scale: 0 (never has occurred), 1 (has occurred once in the last year), 2 (has occurred twice in the last year), 3 (has occurred between three and five times in the last month), 4 (has occurred between six and 10 times in the last month), 5 (has occurred more than 11 times in the last month), and 6 (has not occurred in the last year but it has happened sometime in my life). Participants who scored 0 (50.3%) across all items were categorized as nonvictims, and participants who scored other than 0 (49.7%) on at least one of the items were categorized as victims of sexual coercion.

Online sexual victimization

The OSV Scale (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015) was administered. It consists of 10 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale, 0 (never), 1 (1 or 2 times), 2 (3 or 4 times), 3 (5 or 6 times), and 4 (7 or more times), and participants were asked to specify how many times they had ever experienced a range of unwanted sexual experiences (e.g., insistence and threats or coercion; “Somebody has insisted online that you send them erotic or sexual photos or videos against your will”) that could occur when using the internet and the type of victimization (e.g., “Somebody has disseminated or uploaded onto the internet photos or videos with erotic or sexual content from you without your consent”). Participants who scored 0 (58.7%) across all items were categorized as nonvictims; participants who scored other than 0 (41.3%) on at least one of the items were categorized as victims of OSV.

Wanted and unwanted sexting

Participants completed the Sexting Questionnaire (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017) twice. First, three items assessed the frequency with which participants were involved in sexting behaviors and wanted to do so (e.g., “Send written information or text messages with sexual content about you”). Second, to capture whether participants were involved in unwanted sexting behaviors, we again assessed the same three items, specifying in the introduction that sexting behaviors were unwanted: “How many times have you done the following things over the internet or a cell phone without wanting or feeling like doing it?” In both cases, the response format was a 3-point Likert scale (0 = never; 1 = from 1 to 3 times; 2 = from 4 to 10 times; 3 = more than 10 times). In this sample, we obtained Cronbach's alphas of .76 for wanted sexting and .84 for unwanted sexting.

Sexual satisfaction

The Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX; Lawrance & Byers, 1995; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2015) was used. Participants rated their sexual satisfaction on 7-point bipolar scales (very bad-very good; very unpleasant-very pleasant; very negative-very positive; very unsatisfying-very satisfying; worthless-very valuable). Participants' responses were summed, with higher scores indicating greater sexual satisfaction. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was .88.

Life satisfaction

Participants completed the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Cabañero-Martínez et al., 2004; Diener et al., 1985). It comprises five items (e.g., “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”) rated on 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Participants' responses were summed, with higher scores indicating greater life satisfaction. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient obtained in this study was .85.

Analyses strategy

First, Pearson bivariate correlation analyses were performed to test the relationships between study variables. Second, the prevalence of wanted and unwanted sexting was determined based on descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and percentages. Third, two hierarchical regression analyses tested whether sexual coercion and OSV predicted wanted and unwanted sexting behaviors. The sociodemographic factors (i.e., gender, relationship length) were entered in Step 1 (method: enter). Then, to estimate their added value in explaining variance in the criterion variables and to determine their potentially unique contributions, we added sexual coercion as a predictor in Step 2 (method: enter) and included OSV in Step 3 (method: enter) of the regression model. We separately introduced wanted sexting behaviors and unwanted sexting behaviors as criteria throughout each regression analysis. Fourth, after obtaining the results of the regression analysis, we focused on examining the specific effects of both unwanted and wanted sexting behaviors as a consequence of sexual coercion and OSV on sexual and life satisfaction. Two mediation analyses tested whether the two forms of victimization (i.e., sexual coercion and OSV) predicted sexual and life satisfaction via unwanted and wanted sexting behaviors using Hayes' (2013) PROCESS macro (Model 4). Gender and relationship length were included as covariates. Finally, two serial mediation analyses were run to examine the indirect effects of sexual coercion (X) on sexual and life satisfaction (Y) based on rates of OSV (M1) and wanted and unwanted sexting behaviors (M2) using PROCESS (Model 6; Hayes, 2013). Following Hayes' (2013) procedures for testing indirect effects, bias-corrected confidence intervals for indirect associations were estimated based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. Confidence intervals that do not contain zero indicate that effects are significant (p < .05). We computed the abovementioned analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 21).

Results

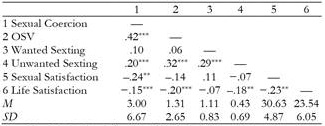

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables.

Note.N = 310. OSV = Online Sexual Victimization.

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001

Prevalence of sexting

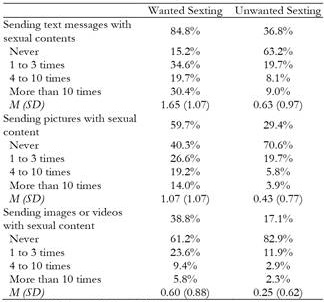

Table 2 displays the prevalence for each type of sexting (sending texts, pictures, or videos with sexual content) that participants had been engaged in, whether wanted or unwanted. Regarding the wanted sexting experiences, sending text messages with sexual content was the most common form of sexting, with a prevalence of 84.8%. Additionally, 59.7% participants sent pictures with sexual content, and 38.8% sent images or videos with sexual content. Of those individuals who engaged in unwanted sexting behaviors, 36.8% sent text messages with sexual content, 29.4% sent pictures with sexual content, and 17.1% sent images or videos with sexual content involuntarily.

Predicting sexting behaviors

Table 3 shows the results from the hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting the participants' willingness to engage in both wanted and unwanted sexting behaviors, based on sexual coercion and OSV, controlling for participants' gender and whether they were involved in a romantic relationship.

Table 3. Predictors of Sexting.

Note.N = 310; OSV = Online Sexual Victimization;

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001

For the wanted sexting behaviors, when demographic characteristics were controlled in Step 1, our results revealed in Step 2 that suffering sexual coercion was indicative of a greater level of sexting behaviors. However, our results showed that after the incorporation of OSV in Step 3, none of the variables emerged as significant (all ps > .05). Therefore, neither sexual coercion nor OSV explained why individuals engage in wanted sexting behavior.

Regarding unwanted sexting behaviors, the sexual coercion victimization significantly contributed to the prediction of unwanted sexual behavior in Step 2, even after accounting for demographics. Moreover, the inclusion of the OSV yielded a significant contribution to the prediction of unwanted sexual behavior beyond the demographics and sexual coercion. As Table 3 illustrates, participants who had suffered OSV were more prone to engaging in unwanted sexting behaviors. Moreover, the amount of explained variance of unwanted sexting behaviors increased by 7% in this last step of the regression analysis. The observed increase was statistically significant, F(2, 309) = 10.06, p < .001. Furthermore, the addition of the OSV as a predictor in the last step caused the sexual coercion to no longer significantly predict sexting behaviors. Therefore, according to Hypothesis 1, elevated OSV emerged as the main predictor of the tendency to engage in unwanted sexual behavior.

The effects of sexting behaviors as consequences of sexual coercion and OSV on sexual and life satisfaction

Given sexual coercion and OSV had only a predictive role on unwanted sexting behaviors in the previous regression analyses, we focused on analyzing the effects of unwanted sexting behaviors on sexual coercion and of OSV on sexual and life satisfaction. Our results about wanted sexting behavior are available as supplementary material.

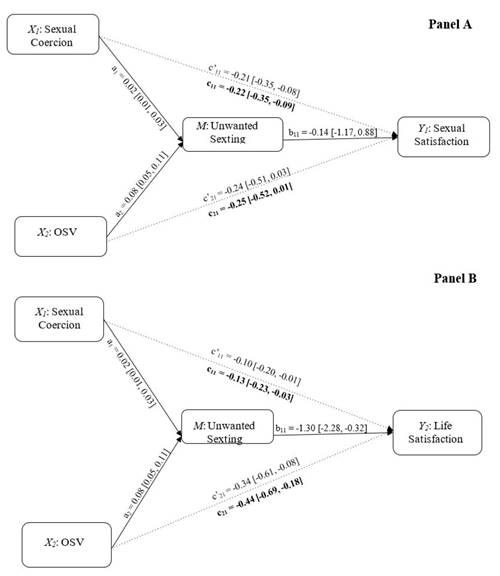

As Figure 1 (Panel A) shows, the associations between both sexual coercion and OSV and unwanted sexting behaviors were significant. However, unwanted sexting behaviors were not related to sexual satisfaction. Therefore, the results showed that sexual coercion, b= −0.00, SE = .02, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.03], and OSV, b = −0.01, SE = .03, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.03], were not indirectly linked to sexual satisfaction via their effects on unwanted sexting behaviors.

Figure 1. Mediation model displaying the indirect effects of sexual coercion and online sexual victimization (OSV) on sexual satisfaction (Panel A) and life satisfaction (Panel B), via unwanted sexting behaviors. Unstandardized estimates, with their 95% CIs reported between parentheses. Total effects appear in bold text.

Conversely, Figure 1 (Panel B) reveals that sexual coercion and OSV were related to increased unwanted sexting behaviors, which also diminished life satisfaction. The results confirmed that the indirect effect of sexual coercion, b = −0.03, SE = .01, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.01], and OSV, b = −0.09, SE = .06, 95% CI [−0.22, −0.01], on life satisfaction were driven by enhanced unwanted sexting behaviors. According to Hypothesis 2, this pattern suggests that suffering sexual coercion and OSV increases the likelihood of engaging in unwanted sexting behaviors, which, as a consequence, decreases individual life satisfaction.

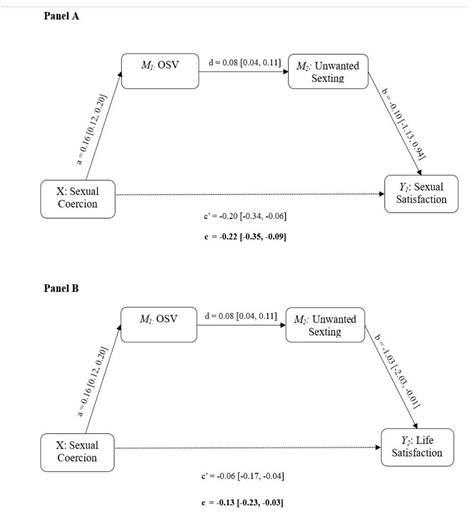

Finally, to test whether higher sexual coercion experiences predict a higher number of OSV experiences, which will lead to a higher probability of engaging in unwanted sexting and then will result in lower sexual and life satisfaction, two serial mediation analyses were run. As Figure 2 (Panel A) illustrates, the results did not yield an indirect effect of participants' sexual coercion on sexual satisfaction, b = −0.00, SE = .00, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.00] via the effect of sexual coercion victimization on increased OSV and increased unwanted sexting behaviors. Conversely, consistent with Hypothesis 3, participants' sexual coercion was indirectly linked to lower life satisfaction, b = −0.01, SE = .01, 95% CI [−0.04, −0.01]. Specifically, as Figure 2 (Panel B) displays, greater sexual coercion victimization was associated with increased OSV, which, in turn, was associated with increased unwanted sexting behaviors and finally was related to lower life satisfaction. This pattern suggests that suffering sexual coercion is related to life dissatisfaction by increasing the likelihood of suffering OSV and engaging in unwanted sexting behaviors.

Figure 2. The effects of sexual coercion on sexual satisfaction (Panel A) and life satisfaction (Panel B), mediated serially online sexual victimization (OSV) and unwanted sexting behaviors. Unstandardized estimates, with their 95% CIs reported between parentheses. Total effects appear in bold text.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to expand the empirical evidence on the prevalence, predictors (sexual coercion and OSV), and consequences (sexual and life satisfaction) of the phenomena of sexting, taking into account both wanted and unwanted sexting.

The first goal of this research was to analyze the prevalence of both wanted and unwanted sexting in Spanish adults. The results showed more people were engaged in wanted sexting experiences than in unwanted sexting experiences, regardless of the way that sexting was carried out (sending text messages, pictures, or videos). The prevalence reported by the participants of this study agrees with that found in previous research, where the wanted sexting behavior was more frequent than the unwanted (e.g., Ross et al., 2019). Furthermore, sending text messages with sexual content was reported more commonly than sending pictures or videos, in accordance with similar studies (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017; Garrido-Macías et al., 2021).

The second aim of this study was to identify how the experiences of sexual coercion and OSV may influence the probability of engaging in both types of sexting. According to Hypothesis 1, both elevated sexual coercion and OSV predicted the tendency to engage in unwanted sexual behaviors. This result supports the findings in previous research (Katz & Tirone, 2010; Ross et al., 2019), demonstrating that individuals with a higher number of sexual coercion and OSV experiences tend to get more involved in unwanted sexting behaviors. Nevertheless, sexual coercion no longer predicted unwanted sexting behaviors when we simultaneously considered the predictive ability of the OSV. Together, our findings revealed that the OSV was a stronger predictor of unwanted sexting behaviors. In addition, its inclusion in the hierarchical regression analyses significantly accounted for the incremental criterion variance beyond demographics and sexual coercion. Regarding wanted sexting behaviors, neither sexual coercion nor OSV predicted individuals' involvement in such behavior, supporting Hypothesis 1. Despite the fact that previous literature has shown an association between sexual coercion, OSV, and sexting (e.g., Choi et al., 2016; Gámez-Guadix & Mateos-Pérez, 2019; Fest et al., 2019), most of those studies did not specifically ask participants about “voluntary” sexting, failing to differentiate between wanted and unwanted sexting (e.g., Choi et al., 2016; Marengo et al., 2019; Wood et al., 2015). With that in mind, future research should take a closer look at whether the sexting reported by the participants has been wanted or unwanted and test whether the findings found here are replicable.

The last objective of this research was to analyze the effect of wanted and unwanted sexual behaviors as a consequence of sexual coercion and OSV on sexual and life satisfaction. First, the results revealed that victimization experiences predicted life satisfaction via unwanted sexting behaviors, such that individuals with higher experiences of sexual coercion and OSV have a higher probability of engaging in unwanted sexting behaviors, which results in lower life satisfaction. These findings support Hypothesis 2 and previous research by demonstrating the relationship between victimization experiences, sexting behaviors, and lower life satisfaction (Fest et al., 2019). In the same way, other studies have shown negative consequences from unwanted sexting behaviors (e.g., Drouin & Tobin, 2014), finding that among women, the frequency of consenting to unwanted sexting was significantly related to anxious attachment. In addition, receiving unwanted sexts was associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and lower self-esteem (Klettke et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2021).

Furthermore, consistent with Hypothesis 3, suffering unwanted sexting is related to life dissatisfaction by increasing the likelihood of suffering OSV and engaging in unwanted sexting behaviors. These results support the findings of previous research by demonstrating the positive associations between sexual coercion and OSV (Kernsmith et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2021) and between OSV and sexting behavior (Gámez-Guadix & Mateos-Pérez, 2019; Wood et al., 2015) and the negative correlation between sexting and life satisfaction (Fest et al., 2019) and go one step further by testing the indirect effect of sexual coercion on life satisfaction through OSV experiences and unwanted sexting.

Finally, unwanted sexting behaviors were not related to sexual satisfaction, so we did not find an indirect effect of sexual coercion and OSV on sexual satisfaction via unwanted sexual behavior (Hypothesis 2) or an indirect effect of sexual coercion on sexual satisfaction via OSV and unwanted sexual behavior (Hypothesis 3). These findings are contrary to the results of past research (e.g., Brodie et al., 2019; Galovan et al., 2018). Nevertheless, other studies have shown that sexting positively correlates with relationship satisfaction (Parker et al., 2013; Stasko & Geller, 2015) and sexual satisfaction (Stasko & Geller, 2015). These opposite results are probably due to the other researchers' failure to identify whether the sexting carried out was wanted or unwanted, so it is important to clearly distinguish the type of sexting behavior in future studies to be able to compare the results and determine whether our findings are replicated.

Limitations and future studies

Despite the relevant contribution of this research to expanding the knowledge on the prevalence of wanted and unwanted sexting behaviors and their association with sexual victimization and satisfaction, our study had some limitations.

Future work in this area could recruit a more ethnically and geographically diverse sample and by utilizing more extensive measures of the outcomes of interest (Ross et al., 2019). Moreover, because of the smaller subsample of men, our results should be considered even more tentative and in need of replication with a broader and more equitable sample of men and women. Likewise, sexual orientation must be examined in more detail in future studies, because research has shown that sexual minorities have more sexual purposes than heterosexual people, and LGBTQ people are more often victims of OSV than heterosexual people (Van Ouytsel et al., 2021).

Conclusions

This study contributes new knowledge regarding the prevalence of both wanted and unwanted sexting in Spanish adults, the association of both types of sexting with online and offline sexual victimization, and the consequences of both types of sexting on sexual and life satisfaction. Specifically, the results from this research indicate that more people have been engaged in wanted sexting experiences than in unwanted sexting experiences. Additionally, our findings revealed that individuals with more experiences of sexual coercion and OSV have a higher probability of engaging in unwanted sexting behaviors, which results in lower life satisfaction. The findings presented here highlight the importance of asking participants about voluntary sexting in order to differentiate between wanted and unwanted sexting, because of the association found in previous literature between unwanted sexting, sexual coercion, and OSV.

Despite the fact that the prevalence of wanted sexting is higher than the prevalence of unwanted sexting in this research, work must continue on the factors that affect the occurrence and perpetuation of the latter due to associated negative consequences for victims. These consequences affect women more negatively, because the free expression of women's sexuality is not in accordance with established social norms (Krieger, 2017; Rodríguez-Castro et al., 2018). In this way, the results of this study suggest potential avenues for the study of variables as gender stereotypes (Van Ouytsel et al., 2021) or sexist ideology (Expósito et al., 1998; García-Cueto et al., 2015). We suggest that the scope of educational literature addressing unhealthy dating behaviors should be expanded to specify the difference between unwanted sexting and wanted sexting because nowadays, the latter is considered a new form of interpersonal communication that allows people to maintain sexual interactions, and it has been associated with positive consequences when done willingly (Döring, 2014; Drouin et al., 2017). Furthermore, data on the motives for sexting (Thomas, Binder, & Matthes, 2021), particularly the motives for unwanted sexting (Garrido-Macías et al., 2021), may be informative here and represent a next step in this line of research. A relationship has been found between motivations for sexting and aggressive online and offline behaviors (perpetration and victimization; Bianchi et al., 2021).

In summary, developing a better understanding of patterns of sexting, especially unwanted sexting, and the associated risks is a significant social and public health concern with implications for people's romantic and sexual lives (Garcia et al., 2016). The important role of education for properly and respectfully sexting can be framed in a broader scope on gender stereotypes, sexual assault, and sexual abuse (Van Ouytsel et al., 2021). On the other hand, open education regarding sexual matters is necessary so that women who are suffering from violent behavior related to unwanted sexting can report it and thus be able to avoid the negative consequences it entails (Wolak & Finkelhor, 2016).