Introduction

In many western countries the increasing of the elderly population and the rising numbers of older people living in nursing homes led to a change in the patterns of care provision for this population (Fu et al., 2019). Portugal is not an exception to this pattern (e.g., between 1998 and 2009 the number of nursing homes increased 89%) (Ministério do Trabalho, 2019). However, the expansion of the eldercare sector often faces shortage of workforce (Sejbaek et al., 2013). Caregivers are a separate professional population from nurses or physicians who care for elderly living in nursing homes since they often have a limited training for their profession, and they must provide care to elderly under the supervision of other health professionals. Moreover, like in other caring professions (e.g., nurses) due to the supply-demand issues caregivers cannot be easily substituted and they are frequently asked to do more work (care for more patients, to do more tasks) in less time and with fewer resources (Buckley et al., 2021). In the attempts to address the rising demand for caregivers to work in elderly care sector, several studies have sought to investigate and clarify factors related to the job and workplace conditions that impact eldercare professionals. In the light of this concern many studies focused on the negative consequences related with job-related factors of professionals working in nursing homes (Brannon et al., 2002; López et al., 2021; Sánchez et al., 2015). Working in nursing homes involves mainly service oriented jobs. In line with theories about emotional labor (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Grandey, 2000), research shows that many service-oriented jobs require workers to display of positive emotions and hide negative affect (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Groth et al., 2009; Jeon et al., 2022). As such, working in nursing homes is emotionally demanding since it requires to perform, daily, a lot of emotional labor. Literature on emotional labor identified two main ways in which workers may conform to display rules within the work contexts: deep acting and surface acting. While deep acting entails an attempt to change actual feelings to meet the required displays by the organizational culture, surface acting involves trying to change affective displays without changing primary feelings (Grandey, 2000). Research also identified that deep acting may have both advantages and disadvantages for the workers, as surface acting has proved to have detrimental effects on workers causing psychological strain (Hulsheger & Schewe, 2011). Theories of emotional labor (e.g., Grandey, 2000) and applied research (e.g., Scott & Barnes, 2011), have focused almost exclusively on its effects on the worker role and workplace. Drawing on work-family relations literature it is well documented that the work experiences spills over workers on after-work life, namely on family life even after they leave the workplace (Ebyet al., 2010; Kossek & Ozeki, 1998). Thus, the effects of emotional labor might not be restricted to the workplace but may also spill into the family domain because of work-family conflict. Moreover, studies show that work-family conflict not only impairs the family domain but also have impacts on the workers' role by increasing, for example, the stress levels (Hammeret al., 2004) and turnover intentions (Kossek & Ozeki, 1999). A meta-analysis focused on consequences of work-family conflict identified work related negative outcomes (e.g., burnout, and absenteeism), family-related negative outcomes (e.g., family satisfaction, parenting satisfaction), and individual negative outcomes (e.g., health problems, stress, anxiety, sleep problems) (Amstad et al., 2011). Studies carried out with samples of in health care workers (e.g., nurses and nurse assistants) showed that these workers face high risk for work-family conflict and its negative consequences (Cortese, Colombo, & Ghislieri, 2010). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to extend previous research that claims that emotional labor can have implications at the work level but can also cross the work boundary to family life, by analyzing the relations between emotional labor and work-family conflict among a sample of caregivers working in nursing homes.

Theoretical Background

Emotional labor

Seminal work by Hochschild (1983) defined emotional labor as the need for the management of workers' emotions to comply with organizational or occupational emotional displayed rules. Many organizations, mainly service oriented organizations, recognize this, and encourage workers to "put on a happy face," regardless of the workers' true feelings and thoughts (e.g., Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Hochschild, 1983). Hochschild (1983) described emotional labor as a form of work that ‘‘requires one to induce or suppress feeling to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others'' (p. 7). In line with Hochschild's definition of emotional labor three features can be identified: it involves worker contacts with other people and these interactions are face-to-face; workers' emotional displays are shaped to others' emotions and in line with organizational culture requirements that outlines workers' emotionally desired expressions. Managing the emotions in the workplace can be achieved by workers using different strategies, as argued by some authors: it can involve surface acting, that includes hiding workers' real feelings or expressing fake emotions to meet up display rules without changing their inner states and showing an adequate emotional display (Morris & Feldman, 1996; Steinberg & Figart, 1999) or deep acting, when workers try to actually experience the required emotions and change their inner feelings (e.g., reevaluate a negative emotional experience) (Morris & Feldman, 1996; Steinberg & Figart, 1999). Grandey's model (2000) suggests that these strategies, surface, and deep acting, are similar to an emotional regulation process that erodes personal resources. In fact, some studies found that surface acting is associated with higher negative work-related outcomes than is deep acting (Hulsheger & Schewe, 2011; Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2012). Other studies found that surface acting spills over other life domains and generates work-family conflict (Montgomery et al., 2005; Montgomery et al., 2006; Seery et al., 2008; Wagner et al., 2013).

Work-family Conflict

Dealing with the demands of work and family roles always remains a critical challenge for workers. Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) defined that work-family conflict (WFC) occurs when “role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (p. 77). Netemeyer et al. (1996) proposed a model that assumes that work-family conflict can have three different forms: (1) time-based conflict, (2) strain-based conflict, and (3) behavior-based conflict. In their review Grzywacz and Marks (2000) state that work-family conflict involves two distinct sources and can be bidirectional: when work demands spillover into family life (work interference with family life), or family life spills over into work (family life interference with work). Since WFC can have several antecedents. Carlson et al. (2000) and Lapierre and Allen (2006) suggested to distinguish between the WFC being strain-based and time-based conflict. Thus, a time-based conflict arises when time pressures associated with one role prevent one from fulfilling the expectations of another role. Strain-based conflict is experienced when strain in one role negatively impacts the performance other life role (Carlson et al., 2000). Turning to the work-family literature, as demands of work domain conflict with the demands of family role the inter-role conflict can arise impacting, not only workers' wellbeing, but also having detrimental outcomes on the performance of the worker role (Hsu, 2011; Kossek et al., 1999; Obrenovic et al., 2020). A meta-analysis that analyzed the negative consequences of work-family conflict by Amstad et al. (2011) found work related negative outcomes (e.g., low levels of job satisfaction, burnout, intention to turnover, and increased absenteeism levels) and family-related negative outcomes (e.g., low levels of marital and family satisfaction), and health related negative outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety, and psychological strain). Within the sector of elderly care, a study by Estryn-Behar et al. (2012) carried out with geriatric care workers in 10 European counties reported high levels of work-family conflict increased the levels of stress and burnout among these professionals. It is also important to note that caregivers working in nursing homes are mainly women as it is showed by the study of Estryn-Behar et al. (2012) that registered that woman involved in paid caregiving for elderly care outnumber, by far, men. The same reality is found in Portugal (CITE, 2019). Moreover, in general, and at the country level, research shows that since women perform most of the work within the family, they experience higher levels of WFC when compared to men (Matias et al., 2012; Perista, et al., 2016).

Emotional labor and work-family conflict

A few notable studies have addressed the relationship between emotional labor and work-family conflict. Wagner et al. (2013) study broadened Grandey's model by analyzing the impact of emotional labor - surface acting - beyond work-related results. The authors showed that surface acting influences the families of workers, as well as the workers themselves, by confirming that engaging in high levels of surface acting during the workday generates strain-based work-family conflict during the evening. Using samples of health care professionals Montgomery et al. (2005) and Montgomery et al. (2006) analyzed the relationship between emotional labor and work-family conflict finding that surface acting was a significant predictor of WFC for doctors, but not nurses (Montgomery et al. 2005). In the study of Montgomery et al. (2006), that included both surface and deep acting, only surface acting was related positively to WFC. Later, another study by Seery et al., (2008), also with health professionals, found that surface acting was related positively with time and strain-based work-family conflict. Overall, the literature suggests that professionals, and health professional in particular performance of emotional labor produces strain, often resulting in negative outcomes that extend over the work domain. However, these prior studies were carried out with specific groups of health professionals, such as nurses and doctors, being this study the first, to our knowledge, to address this issue with a sample of caregivers working in nursing homes.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this study included elderly caregivers working full-time in nursing homes in the north and center of Portugal. The selection criteria required the participants to be working full-time in nursing homes and had to be caregivers who spent most of their workdays interacting with elderly clients. All participants were women (n = 23) aged between 24 and 66, with a mean age of 34.29 (SD = 12.96). Most of the participants reported working a standard day shift (n = 10) with the remaining (n = 13) working nonstandard or rotating shifts including nights. They worked in two types of institutions, non-profit or private institutions (13) and public institutions (9).

Data Collection

Given the intersection of the topics addressed by our research, a qualitative and exploratory methodology was used. The qualitative approach allows to have a deeper understanding of the experiences and feelings about the main topics that this research aims to target and, as such, a semi-structured interview was used for data collection. The sample was purposely recruited from the professional networks of students enrolled in a master program in Gerontology and it was a convenience sample. After being granted authorization from directors of nursing homes approval to conduct the research, participants were recruited through invitations by the master students. Following an explanation about the goals of the research project participants gave free and informed consent to participate, as well as for audio recording of the interviews. There was no financial compensation for participating in the study. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview script with the following general themes/questions. For the present study only three main themes will be analyzed: (1) the main challenges associated with the need to display emotional labor when caregiving; (2) experiences and feelings associated with work-family conflict and (3) experiences and feelings associated with the impact of displaying emotional labor on the perceptions of work-family conflict.

Data analysis

The interview transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), which is an extensively used method for identifying patterns and themes within textual data. This approach is particularly useful in cases where the research question is broad, and the goal is to identify and describe participants' experiences and feelings. According to Braun and Clarke (2006), a code book technique was used, which involves early theme development with certain themes developed prior to coding, after some data familiarization (reading and re-reading data to become intimately familiar with its contents). Braun and Clarke's (2006) six-step process for conducting thematic analysis was followed. During the first phase, authors became familiar with the data by analyzing the transcripts. As a second phase, codes were written, and themes were generated. Phase three involved reviewing the initial themes and subthemes. During phase four, both researchers checked whether the data bounded together meaningfully within each theme. In phase five, each theme was regard as definitive, and in the sixth phase, a report was written based on excerpts from participants selected to illustrate each theme. These themes are discussed further in the following section.

Results

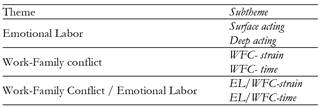

The thematic analysis of interview transcripts yielded three main themes within participants' experiences and feelings: (i) the display of emotional labor, (ii) experience of work-family conflicts and (iii) the relation between the display of emotional labor and work-family conflict. Table 1 illustrate the thematic structure of the themes, including the subthemes. The results are described in a thematic structure of these themes, including the subthemes using excerpts from transcripts that are accompanied by a code identifying the participant.

Emotional labor

Emotional labor is a concept that illustrates how workers' control their emotions to have a positive emotional impact on their colleagues and customers (Hochschild,1983). It involves two main mechanisms: deep acting and surface acting. Although both surface and deep acting have the same goal of compliance to displayed rules, Grandey (2000) noted that with surface acting individuals try to suppress unwanted feelings by faking appropriate displays, whereas with deep acting, individuals use strategies like cognitive reappraisal of the situation to create desired affective states. As a result, surface acting is linked to a higher number of unfavorable outcomes than deep acting (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011).

Surface acting

The display of surface acting, by hiding felt (negative) emotions was mentioned by all the participants and it was considered as part of their job. They often report that they display emotions that are not experienced when caring for the elderly. [P#2“Yes, it happens often. When I'm not ok due to a personal condition, when I get to work, I have to show a smile. I cannot show a negative face because it triggers negative energies that are transferred to the elderly. They're not responsible that I'm not ok”]. Hiding negative emotions was reported as something that is hard to manage but it should be done to perform the work properly. As one participant notes, [P#9: “Sometimes it's hard. We are tired, feeling stressed out and it becomes hard to put a smile in the face. But we must do it, so the older people don't feel what we are dealing with negativity”]. It is notable that all participants verbalized the importance of hiding the negative emotions to avoid the transmission of these negative feelings to the elderly they care. As one participant says: [P#12: “Yes, it happens. There are good and bad days. Some days I have a physical pain I put what I call “a mask”. I try to talk more to distract the seniors so that they do not find that I'm not well”.]

Deep acting

In what concerns deep acting - changing the inner feelings to better adjust to the work requirements - it is also reported by many participants. One participant provides a clear reflection: [P#11: “It is not possible to hid feelings. I think we have to manage those days when we are not so well, not expose ourselves so much, for example, having a slightly smoother day”]. However, it also observed that this cognitive reappraisal is complex and involves behavioral changes. As one participant says [P#21: “But I think it is very important to know how we are doing, because most of our communication it is non-verbal, and even if we want to show that we are doing very well, our body is saying no and the elderly understand perfectly”.] Another participant refers: [P#10“I always try to put aside my personal problems at home, smile and do my job in the best way”]. Or, according to another participant [ P#19: “I'm not the one to show my feelings when something goes wrong in my personal life or at work.”]. The importance of reframing the inner feelings is recognized as important and frequent, as one participant points out [P#16: “I do not hide feelings. We have good relations in the team and when something goes wrong, we talk about it. We don't need to hide it, on the contrary, our team often supports us, which is great. We are just people, and we all have good days and bad days and it's great to have someone with who we can share our concerns, and this helps us to change our feelings”.]

Work-Family Conflict

Work-family conflict is produced by simultaneous "pressures from work and family roles that are mutually incompatible," according to Greenhaus and Beutell (1985, p. 77). These authors further state that work-family conflict occurs when one role's expectations collide with those of another role. This role incompatibility is felt by most of the participants. As one participant reports [P#10: “We work with vulnerable people, with work with emotions and this is something you cannot not switch off after work”]. In fact, when opposing demands of work and family arise, this is likely to deplete workers' psychological resources (Byron, 2005). Since WFC can have several antecedents, in with Carlson et al. (2000) and Lapierre and Allen (2006) it is important to distinguish between the WFC being strain-based and time-based conflict.

WFC- Strain-based

Most of the participants felt that strain caused in their work spillover their family life. Additionally, they report that the emotional strain that they must face when caring for the elderly clients extends over the work role boundary and spillover their family life. As one participant say [P#15“We work with vulnerable people, we work with emotions, and this is something you cannot not switch off after work”.] It also becomes clear from the reports that even when they are in their off-work time they remain available and think about their work. One of the participants observes [P#16 “I'm always available for work and I only “turn off” of work demands if I have a free days. And even during free days I get myself thinking about the work that I must do, On the daily basis if I have some personal (or family) unresolved problem I have to put off the mask and keep working.”]

WFC- time -based

In what concerns time based WFC many authors that focused on relationship between work and family identified, among others, the importance of time pressures in generating WFC (Eby et al. 2010). Participants reflected on the importance of time constrains associated with their jobs, and they can create WFC, as well as the implications for their family lives [P#3“I would like to spend more time with the family to support them whenever possible (e.g., I would like to share more meals with my family, support and accompany a family member on the way to an appointment, etc.). But this is rarely possible. It only happens when I have a day off”.]. Time availability for work and for family seems unbalanced and participants recognize that this unbalance is hard to avoid. One participant says [P#10 “I'm always available for my work and not always that available for family. I need support from other family members otherwise I cannot have the things (at home) done”. Or they complain that: [P#15“Despite the fact that I always try to have time available for the family, there are always work demands that collide with family time. A large “slice” of my time goes to work”.]

Emotional labor and WFC

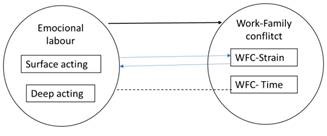

This study aimed to explore the relationships between emotional labor, surface acting and deep acting and two types of work-family conflict, strain-based conflict, and time-based conflict. The findings are consistent with research that explored the association between surface and deep acting and work-family conflict (Montgomery et al. 2006; Seery et al., 2008). Figure 1 depicts the relations between emotional labor and work-family conflict found in the present study.

It can be noted that the relation between emotional labor and work-family conflict was reported by most of the participants. As one participant noted: [P#12:“Sometimes when we deal with elderly people with dementia problems, I think it's very emotionally demanding. And it comes with you after the workday”.]. Even though the spillover effects of work into family life after the workday is highly referred, this participant clearly states it [P#14: “I think this work is quite demanding from an emotional point of view. Sometimes I feel emotionally tired, I do not sleep well and when I get back to work, I must hide how I feel. It is just what we do at work. It is how we feel after the workday that keeps me from having enough rest.”]. The emotion drain from work to family life is also reported by another participant: [P#3: “When I am at work, I must put a mask for eight hours. But it is not the same at home. I often feel tired and all I can think about is resting”.]

Overall, these results are in line with studies that showed that emotional labor tends to increase stress among workers with negative impacts both on the workplace undesirable outcomes as well as in their personal lives (Zaghini, et al., 2020). However, in what concerns the links between emotional labor and time based WFC the results did not show a clear presence of this link. Only one participant notes: [P#5: “Sometimes I have long shifts and I feel bad, because I miss my family and I care if all is fine”.].

Discussion

In this study we explored the experiences of displaying emotional labor and work-family conflict, as well as their relationship with a sample of caregivers working in nursing homes. As stated by Wagner et al. (2013) when workers perform their work tasks there are cases when a given worker experiences feelings and emotions that could be inconsistent with organizational required displayed rules. When this occurs, in the attempt to comply with display rules, workers can engage in one of two forms of emotional labor: surface acting or deep acting (Wager et al., 2013). This is particularly visible in-service oriented organizations and particularly in organization of health sector. Understanding the consequences of this is increasingly important since, like in other health care professions, there is a potential that effects of emotional labor impact the experiences of work-family conflict. Given that work-to-family conflict has been connected to how workers engage with their families (Greenhaus & Powell, 2003), there is a potential that emotional labor extends to both work and family roles. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to examine the process through which emotional labor impacts WFC for caregivers working in nursing homes. The study allowed to examine not only the presence of the constructs within this specific professional group but also the way they relate to each other. Besides, the present study relied on a qualitative approach to have a deeper understanding of the links between emotional labor and the experience of WFC.

The findings indicated that the strain-based conflict is the more prevalent form of WFC conflict linked with both surface acting and deep acting. This result is in line with the concept of strain based WFC, which is defined as crossover type of strain from one role that affects the performance in another domain (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). This indicates the surface acting is the most important dimension that impacts the WFC, rather than the time or behavioral based forms of pressure caused by emotional labor that creates WFC. One possible explanation for the lack of evidence linking time-based conflict and performance of emotional labor could be because work time demands are differently experienced by caregivers, with impact mainly on the availability for family. Moreover, as it was stated by Grandey (2000) deep acting involves a cognitive reappraisal of the situation. Thus, this second mechanism aims a more complex approach that was identified in the current study, but it seemed to have a weaker relation with work-family conflict. Overall results of the present study are consistent with research on the spillover process that identified the influence of strains associated with work demands on the experience of work-family conflict (Eby et al., 2010) and with studies that identified an impact of surface acting on WFC (Wager et al., 2013). In fact, one of the main conclusions of the preset study is that caregivers who experience strain at work due to emotional labor are likely to experience WFC, which means that the strain experience at work will spill over their family life.

Conclusion

Caregivers working in nursing homes are often exposed to emotional demanding conditions and often must perform emotional labor while dealing with their daily tasks with the elderly clients. Moreover, as this study shows they are particularly vulnerable to suffer from WFC impacted by surface acting. Thus, analyzing the linkage between emotional labor and work-family conflict is an important issue both theoretical and practical implications. At this time, and to our knowledge, there are no previous studies that have considered explored the concepts of emotional labor, WFC and their relations in caregivers working in nursing homes. Therefore, the findings of this study extend previous research that explored these concepts with other health professional groups and advances the understanding of the impacts emotional labor and WFC in this specific professional group.

The findings of this study also have theoretical implications. Results provided support for the importance of the presence of emotional labor at work (Grandey, 2000) in these professionals, and showed that that surface acting and deep acting at work have differential effects on individuals and impacts on work-family conflictual relations. In line with previous theory (Grandey, 2000) and research (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002) surface acting at work was related to more negative outcomes, making an important extension to existing research with implications for work and family conflict (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). The finding that surface acting and deep acting operates differently in work-family conflict suggests the importance of considering the domains of emotional to understand of their impacts more fully on work-family conflict.

In what concerns preventive interventions, this study focuses on the importance of considering the strain associated with emotional labor and WFC, particularly through providing organizational support to caregivers, and not only to other health care professionals that often have more training opportunities to deal with issues related with stress and management of emotions in the work environment. Therefore, considering the needs of the caregivers in their daily activities, by offering more resources and support have the potential to positively impact the wellbeing of caregivers, and ultimately the care they provide to vulnerable patients like the elderly population.

The present study is not without several limitations. The number of participants was limited, and participants were only women. It is, therefore, not possible to generalize the findings from this study to all the caregivers that work in nursing homes within the country. Further studies should consider larger of caregivers both from private and public nursing homes in the country. Moreover, future studies should also consider workers' background variables, including age, gender, education, nonstandard work hours, among others. Another limitation of the study, due to its qualitive nature, is that we cannot determine the quality of the predictive association between emotional labor and WFC. Future studies need to clarify which other work-related factors are associated with emotional labor and WFC to validate the conclusions from the present study. Overall preventive interventions that focus on the importance of considering the strain associated with emotional labor and WFC, particularly through providing organizational support to caregivers, have the potential to positively impact the wellbeing of caregivers, and ultimately the care they provide to vulnerable patients like the elderly population.