Introduction

Social-emotional skills refer to a set of learned behaviors that are put to work when we interact with others. These skills enable us to express feelings, attitudes, opinions, and to defend personal rights (Zins et al., 2000). Alzahrani et al. (2019) add that they refer not only to how one interacts with others, but also to the ability to manage own’s own emotions and adequately respond to events that happen around us. For their part, Wu et al. (2018) indicate that development of social and emotional competence during early childhood is essential to ensuring preparedness for school, and is associated with many important aspects of life, including academic achievement, behavior, and mental and physical health. Improvement in these competencies is associated with better academic achievement and with positive social behaviors (Bear & Watkins, 2006).

Adequate development of these skills requires the individual’s involvement in a long-term process of learning specific competencies and skills. Therefore, even though these skills can be worked on at any age, it is more productive to introduce them in early childhood, and specifically in the school context (Björklund et al., 2014; Cornell et al., 2017; Diamond & Lee, 2011; Durlak et al., 2010). The stage of primary education is considered a critical period when boys and girls can have different opportunities to practice emotional control and deal with their emotions and social interactions, ensuring continued learning throughout later years of schooling. As one of the most powerful agents of socialization, school contributes not only to the transmission of knowledge but also to whole-person development (Grajales, 2003). Together with other socialization agents, such as family and society, school can play an important role in promoting the learning of social-emotional competencies by taking specific actions.

In recent years, many interventions have been proposed to promote these skills in the school environment. In this line, a wide range of programs have been integrated into the curriculum under the name of Social-Emotional Learning Programs (SEL) (Low et al., 2015). According to Durlak et al. (2011), these interventions can be considered to facilitate the process of developing a set of basic cognitive, affective and behavioral competencies, for managing and recognizing emotions, achieving one’s purposes, acknowledging others' perspectives, establishing positive interpersonal relationships, making responsible decisions, and managing relationships with others in a positive way.

International agencies that collect evidence on interventions, such as the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (2021), point out that in recent years more studies have been conducted in primary schools than in secondary schools. In England, several studies have posited a relationship between SEL interventions and academic outcomes. In the United States, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) (2021) reports on the effectiveness of certain social skills programs, citing results related to academic issues, disruptive behavior, interpersonal relationships, bullying, and so on. In this line, Fernández et al. (2014) report data on the effectiveness of 25 programs that target a population from early childhood education and primary education, finding that 45% of them showed significant differences in favor of improved social competence, and 30.30% showed significant values in reducing behavioral problems, as well as other effects.

Several previous studies mention difficulties in categorizing programs and analyzing their effects, due to a lack of agreement on which skills are being taught, variability in reported results, and a lack of consensus in the foundational theoretical models (Rubiales et al, 2018). The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) (2021) establishes five categories of skills related to SEL, mentioning social awareness, self-knowledge, self-management, responsible decision-making, and relationship management. Fernández et al. (2014) and Pandey et al. (2018) take a different line, classifying programs according to their methodological or procedural characteristics. Elsewhere, McCallops et al. (2019) mention empathy, self-awareness, awareness of others, self-regulation, and motivation. A similar categorization system was established by Goldberg et al. (2019) and Sklad et al. (2012), who organize programs according to their results, grouping them into categories of social and emotional adjustment, behavioral adjustment, scholastic achievement, and internalizing symptoms. This system will be taken as reference in the present study, as it allows greater flexibility for integrating the diversity of information found in these studies.

There is a lack of consensus in categorizing the different programs and in the dimensions comprised, along with great diversity in objectives, designs, methodologies and presentation of results (Rubiales et al., 2018). Many authors have tried to synthesize the existing information in secondary studies that offer a systematic or literature review (Oros et al., 2011; Pérez-Escoda et al., 2012). However, there is still little information on program characteristics and effects organized by stage of education, and there is much variability in terms of the review quality and presentation of the information. The evidence reflected in secondary studies on the subject must be analyzed to obtain a broader and more integrated framework of understanding.

The aim of this study is to identify reviews and meta-analyses that include primary studies on programs to develop social-emotional skills within the school context, at the primary education level; to evaluate the methodological characteristics of these reviews; and to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the programs and their results. The following review questions will be explored:

RQ1: What are the methodological characteristics and quality of the reviews and meta-analyses identified?

RQ2: What is the level of evidence for programs identified in good quality reviews?

RQ3: For programs with higher levels of evidence, what are the main effects reported?

RQ4: For programs with higher levels of evidence, what characteristics do they have (skills taught, components, teaching-learning methodology)?

Method

An umbrella-type systematic review was carried out, including only other reviews or meta-analyses on one specific topic, to be studied and synthesized (Aromataris et al., 2015). The PRISMA methodology (Page et al., 2021) was followed, and we applied the specific recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and other relevant authors for conducting this type of review of reviews (Aromataris et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2011) The protocol meets the criteria required by the International Prospecting of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), and has been registered under the code: CRD42021239217. The entire process of identification, selection and evaluation of studies was carried out by two independent reviewers; after comparing their results, any doubtful cases were resolved by consensus or by appealing to a third reviewer.

Search strategy

The following databases were used: ERIC, WOS, PSYCINFO, SCOPUS and COCHRANE. Key words in English and Spanish were used to identify the resources, making different combinations with Boolean operators: ("meta-analysis"; review; “systematic Review”) AND ("emotional skills"; “emotional competences”; “socio emotional”; “social emotional”; “social skills”) AND (school; "primary school"; “elementary school”; Child*) AND (program*; training; intervention, learning).

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria were established as follows: secondary studies of systematic, narrative or meta-analytic reviews, which reported on application of programs for the development of social-emotional skills carried out within the school environment, having a universal, curricular nature, with a primary school population, between the ages of 5 and 12 years. Scientific articles published in English or Spanish between the years 2000 and 2020 were included. The decision to include narrative or literature reviews was based on the fact that this type of study usually provides more detailed information on the characteristics of the interventions.

Our exclusion criteria eliminated reviews that included studies conducted in the clinical setting or outside the school setting, or which used any specifically-indicated population or students with specific characteristics (e.g., special educational needs or identified disorders). We eliminated primary studies and merely descriptive reviews that did not offer results from program application, or that included studies applied in stages other than primary education, or with subjects under 5 years of age or over 12. We also eliminated studies that did not address social-emotional skills as their main element.

Reviews were selected if they met all inclusion criteria and excluded if they met at least one of the exclusion criteria.

Data extraction and analysis

Following the criteria and recommendations of Aromataris et al. (2015) and Smith et al. (2011), a matrix was designed for data categorization, extraction and analysis. This process was carried out in three phases. In the first phase, data on the general characteristics of all the studies were extracted and analyzed, such as: type of review, type of primary studies included, country and language, period of years covered, population.

In the second phase, the quality of all the selected studies was evaluated. The systematic reviews and meta-analyses were evaluated using the AMSTAR-2 tool (Ciapponi, 2018; Shea et al., 2017), which contains 16 domains that explore general methodological quality, seven of which are considered critical, making it possible to rate confidence in the results of a scale as either High, Medium, Low or Critically Low. The critical domains are: existence and record of a previous protocol (item 2); exhaustive search strategy (item 4); presence of a justified list of excluded studies (item 7); evaluation and discussion of risks for bias (items 9 and 13); statistical analyses and analyses of publication biases (items 11 and 15, which are only applied in meta-analyses). The items are completed with ratings of Yes, No, Partial Yes, Does not apply. Non-systematic literature reviews or narratives were evaluated with the SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) (Baethge et al, 2019), which is composed of 6 items that assess: justification of the review (item 1); objectives (item 2); search description (item 3); references (item 4); scientific argumentation (item 5), and presentation of the data (item 6). Each of these is scored on a three-value scale from 0 (low level) to 2 (high level); the sum of the scores (maximum 12) provides a measure of the quality of a narrative review article. Scores less than or equal to 6 were considered as low quality, scores between 7-9 as medium and between 10 - 12 as high quality.

In the third phase, a list was made of all the programs assessed as medium- and high-quality reviews; data from each of these was extracted and grouped under three headings: I) Program results; II) Level of evidence and III) Characteristics. Under Heading I, in addition to results measured, information was collected on methodological aspects of the primary studies, such as sample characteristics, country of application and duration. The results were categorized into five groups, taking as a reference the studies by Goldberg et al. (2019) and Sklad et al. (2012). The primary results were: (a) Social adjustment (Adj-S) and (b) Emotional adjustment (Adj-E), these refer to general or specific measures of skills that had been improved or worked on during the intervention (e.g. social skills, communication, assertiveness; emotion recognition skills, expression and self-regulation). The secondary results were: (c) Behavioral adjustment (Adj-B), which includes positive social behaviors (e.g. cooperation, altruism), as well as behavior problems (disruptive behavior, aggressivity) and risk behaviors (e.g. tobacco and alcohol use); (d) Academic Outcomes (AO), which includes measures of scholastic achievement in different areas and specific skills (e.g. reading); and (e) Mental Health (MH), taking into account measurements of internalizing symptoms (e.g. anxiety, depression, stress) and well-being. In this phase, only two reviews presented clear quantitative results, so it was not possible to perform a quantitative analysis; instead, a qualitative and descriptive synthesis of the results and reported evidence was conducted.

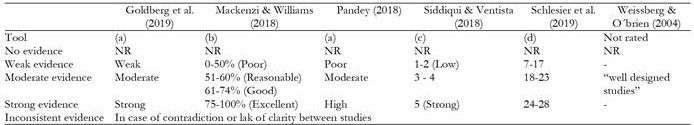

Under Heading II, the programs’ “level of evidence” was recorded: quality of the primary studies, instruments, and summary of evidence. Since the reviews used different tools to evaluate the quality of the primary studies and applied different criteria to classify the evidence, it was necessary to unify the criteria for interpretation. For this purpose, we used an ordinal categorization system based on previous work (Gálvez-Lara et al., 2018). In this manner, 5 levels of evidence were established and can be seen in Table 1: "no evidence," when no results from primary studies are reported; "weak," "moderate," or "strong” evidence, according to the quality reported for the primary studies collected; and "inconsistent evidence," when contradictory or unclear results are reported. As needed, when different primary results were found, the highest rating was taken as the reference, and cases of doubt were resolved by consensus.

Table 1. Ordinal scheme to classify the different levels of evidence.

Notes:(a) Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies; (b) Downs & Black checklist, (c) Ccombination of Maryland Scale of Scientific Method and other criteria; d); Own evaluation system; NR, Not reported.

Finally, taking as a reference the studies by Goldberg et al. (2019), Mackenzie and Williams (2018) and Siddiqui and Ventista (2018), the information collected under Heading III “program characteristics” contained: objectives; skills taught; methodology; theoretical frame of reference; agents who applied the program; components (families, educational community, others); and implementation (resources, reliability).

Qualitative and quantitative data were extracted and analyzed, the latter expressed in terms of frequency, percentages, means, ranges, minimums and maximums.

Results

Selection process

After searching the different databases, 4804 records were identified. After eliminating duplicates, the search was refined according to the eligibility criteria, resulting in 305 documents. After examining the titles and abstracts of all these documents, 280 were excluded. The full text of the 25 articles was evaluated, and 10 articles that did not meet the criteria were eliminated. Finally, for this investigation, 15 reviews were included in the overall analysis, and 6 were subsequently selected for program analysis on the basis of their quality, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Characteristics of the reviews

General characteristics

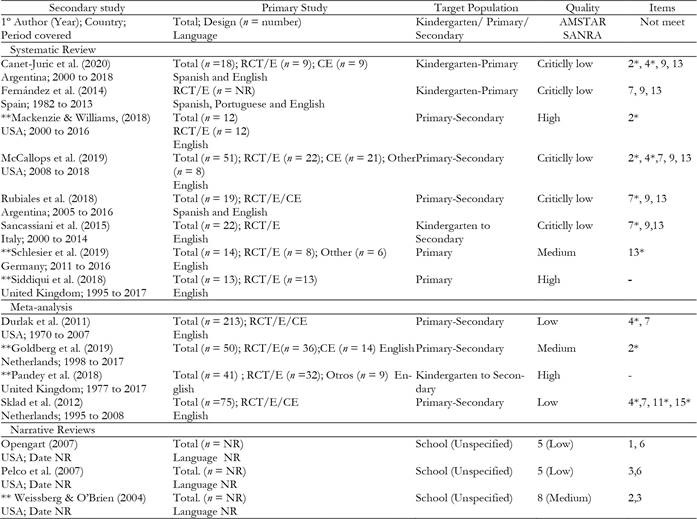

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the reviews analyzed. The main results show that 8 studies (53.3%) were systematic reviews, 4 (26.6%) were meta-analyses, and 3 (20%) were nonsystematic narrative reviews. Nine studies (60%) were published between the years 2015 and 2020, and 40% (n = 6) were from the United States. Twelve studies (80%) included primary studies with experimental or quasi-experimental designs. In 60% of the reviews (n = 9), the language of the primary studies was English only. The three narrative reviews did not report data on the characteristics of the studies included (20%).

Table 2. Characteristics and quality of reviews included.

Note. (**)Moderate or High quality reviews;

(*)Critical items partially met in AMSTAR; CE, Cuasi Experimental; E, Experimental; NR, Not Reported ; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial.

Regarding the programs analyzed, all 15 reviews (100%) included curricular programs, targeting a universal population, and were implemented at the level of primary education. Two of these (13.3%) were exclusive to primary education (Schlesier et al., 2019; Siddiqui & Ventista, 2018), and 13 (86.6%) additionally included students from other ages or stages of education. In the 2 reviews that addressed primary education exclusively, the participants’ age in the primary studies ranged from 5 to 12 years; in the reviews with a mixed population the ages ranged from 3 to 21.

Quality of the reviews

Table 2 presents results regarding the quality and critical elements of all the secondary studies evaluated using AMSTAR-2 and SANRA.

Of all the systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 41.6% (n = 5) showed critically low quality; they did not meet the critical elements related to presenting an evaluation of biases or presenting a list or justification of excluded studies. Three systematic reviews (25%) showed high quality, 2 studies (16.6%) had medium quality, with certain deficiencies in discussing the study biases, and 2 meta-analyses (16.6%) showed low quality.

On the other hand, 2 non-systematic reviews or narratives showed low quality, while one of them obtained medium quality. The most important limitations were inadequate presentation of data and a lack of description of search strategies.

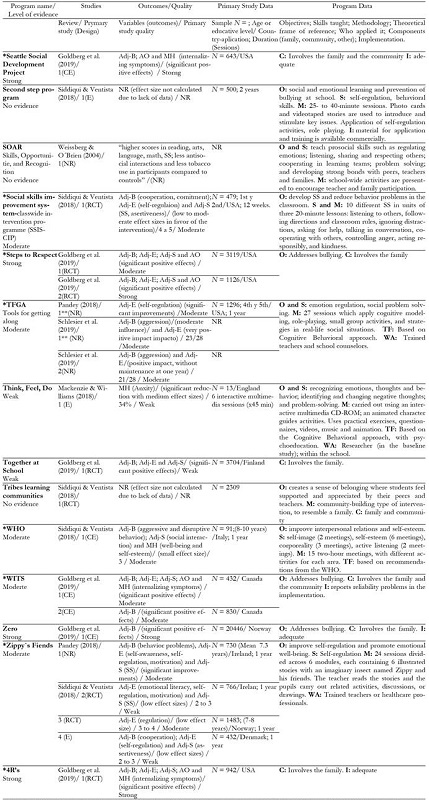

Characteristics of the programs

For the program analysis, we considered only those programs that were reported in medium- or high-quality reviews or meta-analyses (n = 6). A total of 39 social-emotional development programs, applied in primary education, were counted. Table 3 presents the data on level of evidence, results, and characteristics for all of these.

Table 3. Summary of program characteristics and evidence reported in high- and medium-quality reviews.

Note. (*)Programs with moderate or strong evidence;

(**)Using the same primary studies; C: Components; S: Skills; SS, Social skills; I: Implementation; M: Methodology; TF: Theoretical framework; NR: Not reported; O: Objectives; WA: Who applied the intervention; PS: Problem solving; MH: Mental health.

Level of evidence

To establish the level of evidence for each program, the quality of the primary studies and the summary of the evidence reported in each review were taken into account; these elements were reported in 5 of the 6 reviews (83.3%). Three systematic reviews used different tools and criteria to summarize the evidence (ordinal, numeric, percentages), and two meta-analyses used the same instrument, in different versions, and applied similar ordinal criteria. The narrative review did not evaluate the quality of the primary studies. After unifying the criteria for interpreting the evidence (see Table 1), we found that 6 programs (15.3%) were reported with strong evidence; 14 (35.8%) with moderate evidence and 12 (30.7%) with weak evidence. Six programs (15.3%) were considered as having “no evidence”; and one program was rated with “inconsistent evidence”, due to a contradiction between two reviews in the quality analysis of one of the primary studies.

Effects of high- and medium-quality programs

The programs with strong evidence (n = 6) showed significant positive effects in different variables in favor of the intervention, five (83.3%) showed results in Adj-B; 4 (66.6%) in AO; 3 of them (50%) also showed effects in Adj-E and Adj-S; and three in MH; in the latter group, only the FRIENDS program reported results in MH, with significant improvements in social and general anxiety. Effectiveness of these programs was tested through randomized experimental or quasi-experimental designs with control groups and samples of primary school subjects that contained from 643 to 20,446 subjects. Four of the programs (66.6%) were applied in the United States, one in England, and another in Norway.

Programs with moderate evidence (n = 14) presented the following effects. Thirteen (92.8%) showed significant positive results in favor of the intervention in Adj-B; 10 (71.4%) in Adj-E and Adj-C; and 4 (28.5%) in AO and SM. Effects were tested with randomized experimental studies, experimental studies or quasi-experimental studies with samples ranging from 91 to 5081 subjects. Seven of these (50%) were applied in the United States and 2 (14.2%) were implemented in more than one country.

Descriptive characteristics

Among the high-quality programs, one (16.6%) provided more detailed information about its characteristics, the other 5 (83.3%) provided little information; for this reason we decided to group together the programs with strong and moderate quality to present the descriptive characteristics. Together, these represent 51.2% (n = 20) of all the interventions identified (n = 39).

Regarding their components, all of them (100%) implemented activities with the students, 14 (70%) also involved the family and 10 (50%) additionally involved the educational community. Information on who implemented the programs was reported in 7 cases (35%): 6 were implemented by trained teachers, in some cases they were also carried out by professionals, researchers or trained school counselors. Implementation was considered in 9 programs (45%), 7 (35%) reported adequate reliability in implementation; in addition, 5 (25%) presented support materials such as workbooks, manuals, worksheets or videos to facilitate implementation and 2 (10%) mentioned training as an implementation strategy. Nine programs reported their duration (45%), 6 (30%) had a one-year duration, and the number of sessions ranged from 9 to 45.

The objectives were mentioned in 8 programs (40%), 3 (15%) reflected general objectives (to address bullying) and 5 (25%) reported more specific objectives, on 4 occasions relating to Adj-S (e.g. improved peer relations); in 3 cases related to Adj-B (e.g. reducing behavior problems); in 2 programs related to Adj-E (e.g. improving self-regulation), and in 2 programs related to MH (promoting well-being, self-esteem).

Nine programs (45%) described the skills worked on; in 4 of these, objectives and skills could not be clearly differentiated; we decided to include them as skills, considering the way in which they were expressed. Seven skills related to Adj-B were cited: coping, problem-solving, and conflict resolution were mentioned in 4 programs; 2 programs mentioned following instructions and rules; expanding the behavioral repertoire, cooperation, responsibility and kindness were each included in one program. Six skills were related to Adj-S: of these, listening skills were worked on in 3 programs; social skills, dialogue, argumentation, help-seeking and conversational skills each appeared in one program. Five skills were related to Adj-E: of these, cognitive self-regulation (regulating thoughts, perspective taking, reflection) and emotional self-regulation (e.g. control of anger) were mentioned in three; relaxation and identification of emotions and thoughts were each mentioned in two programs. Five skills were related to Academic Outcomes (AO): attention skills were named in 2 interventions; study skills, language skills, organization and planning were each mentioned in one program.

Work methodology was reported in 10 interventions (50%): 9 (45%) referred to an organized, sequenced structure. In addition, 7 (35%) mentioned more specific activities; group work was mentioned in 5 programs, use of games in 2, and use of real-life situations or social stories in one case each. Use of classroom support materials (books, videos, work sheets) was reported in 5 programs (25%). Specific techniques were mentioned in 3 interventions (15%); modeling and role playing in 2 programs, and problem solving in one. The theoretical framework of reference was reported in 4 programs (20%); cognitive-behavioral approach was mentioned in 3 cases (15%), along with social learning and behavioral analysis in one case; another program was based on WHO recommendations.

Discussion

The general aim of this study was to identify and analyze reviews and meta-analyses that included primary studies on intervention programs to develop social-emotional skills in primary education. For this purpose, the umbrella-type systematic review methodology was used. This procedure has seldom been used in this context; we found only one previous study that analyzed the effectiveness of programs published between 1997 and 2007, and incorporating all educational levels (Diekstra & Gravesteijn, 2008). The present research limited its study population to the sphere of primary education, and stipulated a publication period covering the past 20 years. In addition, study and program quality were evaluated, and we incorporated systematic reviews, meta-analyses and narrative reviews, overcoming some of the limitations of the previous study.

Our research identified 15 secondary studies that contain school-based, universal social-emotional development programs, confirming that there are numerous reviews in this field. However, only two reviews were identified that exclusively addressed the primary education population; the rest included two or more different stages of education, meaning that a large part of the data were not segregated. In line with previous findings, the scope of these reviews was found to be very broad and not very specific, as they include heterogeneous populations, with students of all ages, grade levels and stages of education, making it difficult to extract information, and limiting comparison between programs (Miñaca et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2017; Viloria, 2005).

The first review question was directed toward ascertaining the methodological characteristics and quality of the studies identified. We found that most of them were published in the past five years, come from the United States, and incorporate experimental or quasi-experimental primary studies, with control groups. Very few reviews included primary studies not reported in English; in the medium- and high-quality reviews, English was the exclusive language. A potential risk of bias is detected here, as limiting studies to a single language may exclude relevant research or leave out cultural considerations; this may have a negative impact on generalization and interpretation of results (Jackson & Kuriyama, 2019; Stern & Kleijnen, 2020).

Regarding quality, 60% of the secondary studies presented low or critically low quality. The systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as a whole, comply with the basic methodological aspects; however, most of them do not comply with such fundamental aspects as evaluation of biases, explanation of reasons for excluding studies, or application of blind peer reviewing. On the other hand, the overall low quality of the non-systematic or narrative reviews was related to shortcomings in data presentation, reporting of search strategies, selection criteria, objectives and justification. Other umbrella reviews conducted in the educational field find similar results, regardless of whether they are systematic, meta-analytic or literature reviews, mainly mentioning the lack of transparency in the methods used as the central element affecting the reproducibility of research in this field (Barbosa et al., 2020; Gessler & Siemer, 2020).

For their part, the six reviews with moderate or high quality reflected an acceptable level of confidence in their results; for this reason they were selected for the next phase of answering the second review question, related to the level of program evidence. In this phase 39 programs were identified, and we determined the level of evidence for each of these. The general results showed that the reviews show different ways of studying and presenting the evidence, they apply different instruments and report values expressed in numerical ranges, percentages or ordinal categories that are not comparable with each other. For this reason, it was essential to unify the criteria for interpreting evidence by applying a nominal system used in previous studies (Gálvez-Lara et al., 2018). We found that half of these programs show moderate to strong levels of evidence. The remainder are split between those that show weak quality, a small proportion of programs with insufficient evidence, and a single program with inconsistent evidence. In this line, other previous studies underscore the high number of existing programs, as opposed to the low quantity and quality of evidence supporting them. By way of explanation, they suggest the characteristics of the primary studies, whose most frequent limitations are sample size, lack of randomization of the subjects, absence of control groups or the absence of follow-on measures (Goldberg et al., 2019; Schlesier et al., 2019; Siddiqui & Ventista, 2018).

In this phase, it is striking that most of the programs appear only in a single review, and they have only one source of support. In this regard, only the PATHS program was represented in all the reviews, and it presented seven primary sources of support; six other programs were included in two reviews only, and for the most part have two primary sources of support (Caring School Communities, Child Development Project, INSIGHT, Positive action, TFGA and Zippy's Friends). Another trend found was the coexistence of primary studies with weak and moderate quality as support for the same program. All this indicates that there is a low level of agreement between the reviews in terms of the programs identified and also in the primary studies analyzed, despite the fact that the time period and general objectives were similar. This variability may be associated with the use of different strategies, search terms, elegibility criteria, and databases. These findings imply that there is still a need for more rigorous research showing robust effects of social-emotional interventions in the school context, and that the scope of secondary studies that synthesize this evidence also needs to be more clearly defined (Siddiqui & Ventista, 2018; Slavin, 2019).

The third review question aimed to establish the primary program effects that were reported. In general, and in line with Rubiales et al. (2018), we found that the variables evaluated were highly heterogeneous; for this reason we grouped the results using the categories defined by Goldberg et al. (2019) and Sklad et al. (2012). We found that the high- and moderate-quality programs presented significant positive effects mainly in one measure of secondary results, that is, behavioral adjustment (Adj-B), most notably a decrease in behavior problems or improvement in disruptive behaviors; other programs showed significant effects in positive behaviors, such as cooperation. Of the primary results, emotional and social adjustment were most often reported as significant, positive results. Significant improvements were seen primarily in emotional self-regulation, followed by emotion recognition and expression; significant improvements were also reported in SSs, communication and interpersonal problem solving. Most of the high-quality programs showed significant positive effects in another secondary variable, academic outcomes (AO), along with other medium-quality programs that also reflected these effects. Finally, a smaller proportion of medium- and high-quality programs reported effects on measures of mental health, mainly reflecting a significant decrease in internalizing symptoms, often mentioning anxiety.

In comparison with results from Diekstra and Gravesteijn (2008), one can observe coincidence in some of the reported effects, confirming that these types of programs significantly improve emotional and social skills, increase academic performance in certain specific areas, and reduce mental problems. As for behavior improvement, the present umbrella review reflects an important role attributed to behavior results, even though such important results were not reported in the studies by Diekstra and Gravesteijn (2008) or Goldberg et al. (2019). In the reviews by Sklad et al. (2012) and Fernandez et al. (2014), the programs reported significant effects on social-emotional and behavioral skills, in similar proportions. One possible explanation for this variability in findings could be the diversity of categories of analysis used in the different reviews, along with diversity in the initial frame of reference (Rubiales et al, 2018). Siddiqui and Ventista (2018) also suggest an explanation in the way results are studied and reported in the primary studies, where social-emotional skills are sometimes studied as a unit, and sometimes are reported as independent variables. This is undoubtedly a limitation for synthesizing and interpreting the findings.

On the other hand, it is difficult to establish which components affect each study variable, due to the lack of clarity in reporting the data. In this regard, few reviews analyze the possible moderators of the effects with any specificity (Goldberg et al., 2019; Sklad et al., 2012). Neither could we analyze program effect size in this review, since this data, as Schlesier et al. (2019) also notes, is rarely reported. Even so, some secondary studies report significant effects in favor of programs with mainly small effect sizes, or moderate in some cases (Goldberg et al., 2019; Mackenzie & Williams, 2018; Pandey et al., 2018). All this may limit our interpretation of the effectiveness of the programs under discussion, as also occurs in previous studies (Canet-Juric et al., 2020; McCallops et al., 2019; Schlesier et al., 2019).

It should also be noted that medium- and high-quality programs have been applied mainly in an English-speaking population, in the United States and England, and to a lesser extent in countries like Norway. This coincides with the trend indicated by certain specialized agencies and in some previous studies (EEF, 2021; ESSA, 2021; Diekstra & Gravesteijn, 2008). Although some programs have been applied in different countries, such as the Zippy's friends implemented in Ireland, Norway and Denmark with rural and urban populations; or TFGA, in white and African-American populations; this is not the general trend. In this matter, we observe a lack of information on sample characteristics in many of the reviews, and there is also a possible risk of selection bias due to the limited representativeness across cultures, races and contexts.

The fourth question aimed to ascertain program characteristics of the programs with the most evidence. In this regard, one difficulty we encountered was the large variation in how descriptive information was reported, along with a high degree of unreported information. Information on objectives and skills worked on was reported in less than half of the quality interventions. In addition, the objectives were expressed in a very general way, or it was not possible to clearly differentiate them from the skills being worked on. Among the objectives, the most notable aims were to address bullying, improve social skills and interpersonal relationships, and reduce behavioral problems. The skills most frequently worked on in medium- and high-quality programs coincide with the results reported, and have to do with behavioral adjustment, especially coping and problem-solving skills; social adjustment, where developing communication skills is the main focus; and emotional adjustment, where cognitive and emotional regulation or relaxation are worked on, among other skills. Some programs reinforce specific academic skills, like attention or planning.

Half of the programs offered data on the working methodology. In general terms, there is a tendency to use structured, active, guided and interactive methodologies in small groups, with the use of cognitive and behavioral modeling strategies, role playing, or problem-solving techniques, along with the use of specific material. The theoretical model of reference is seldom mentioned, though the cognitive-behavioral approach stands out. In the same way, there was little data reported for duration, but the length most often mentioned was about one year. Regarding components, most medium- and high-quality interventions involved the family, and half of them also involved the educational community. The programs were applied by trained teachers or professionals. Noteworthy among the implementation strategies was the use of manuals or specific materials, and training to support the implementation.

The high degree of unreported data precludes a more exhaustive analysis of the characteristics, effects, and possible moderators of program effects.

Authors such as Slavin (2019) highlight the value of secondary studies as resources that help to synthesize evidence for practical purposes, whether for selecting appropriate programs for classroom work, or for making political decisions on implementing broader strategies that are supported by scientific bases. Even though we have found an important number of secondary studies that contain universal school programs for social-emotional development, in future research it would be advisable that the population be segregated by age or stage of education; that primary studies not be limited to the English language; that more precise data be reported on sample characteristics and the context of program application. Primary studies should be extended to diverse contexts; primary and secondary results be reported in detail; possible moderators of these results should be described and analyzed; the quality of the primary studies should be assessed; and clear levels of evidence should be established to facilitate interpretation of the effects. Along the line of reasoning of Joyce (2019) and Slavin, (2019), all of this taken together could help make it possible to generalize findings and establish practical evidence-based recommendations.

texto en

texto en