Introduction

Loneliness is an unpleasant emotional experience, often expressed as feelings of emptiness and abandonment (Dong et al., 2007), that results from the discrepancy between desired and perceived social relationships (Gonyea et al., 2018). In the aging process, these feelings and discrepancy will tend to increase (e.g., Qualter et al., 2015; Shovestul et al., 2020), with research showing that loneliness is pervasive in the aged population (e.g., Vicente et al., 2014). Prevalence data indicate values between 19.3% and 40.0% (Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012; Perissinotto et al., 2012; Shovestul et al., 2020; Theeke, 2009; Yang & Victor, 2011), or even 60.0% depending on the assessment methodology (Lee et al., 2019). Contributing to these numbers are the added functional limitations and consequent social isolation (e.g., Aartsen & Jylhä, 2011; Macdonald et al., 2018). Thus, an older person limited by functional disability will tend to experience reduced contact and greater social isolation (Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 1999). Although loneliness is a different experience from social isolation, it can result from that isolation (Cacioppo et al., 2014). Indeed, loneliness shows a close relationship with decreased personal networks (e.g., Aartsen & Jylhä, 2011; Victor & Yang, 2012) and less social attachment or integration (Tiikkainen & Heikkinen, 2005). Seemingly in contradiction, a lower level of loneliness has been observed to be associated with greater dependence on activities of daily living (ADLs) in older adults living in nursing homes (Drageset, 2004). However, in social care, functional dependence is not associated with the same degree of social isolation or decreased social relationships compared to those living in the community.

Loneliness in older age is a serious problem because of its negative consequences. Regardless of where recruitment of older people took place, it was found that loneliness was a predictor of depression (e.g., Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Vicente et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2018), physical problems, lower life quality, cognitive (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010) and functional decline (Perissinotto et al., 2012), and even death (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Perissinotto et al., 2012). However, among residents from assisted facilities in another study, loneliness did not have a significant clinical impact on functional status or physical health (Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012). In institutionalized settings, functional impairment and poor physical health usually involve more care and support, which probably explains this result.

Inversely, predictors of loneliness in older age include depression (e.g., Lee et al., 2019; Tiikkainen & Heikkinen, 2005), poor health (Dong & Chen, 2017; Hawkley et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2018), and functional disability (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, 2018; Savikko et al., 2005). Other predictors relate to sociodemographic aspects. For instance, several studies with older people point to widowhood (Dong & Chen, 2017; Savikko et al., 2005; Victor et al., 2005), living in a geriatric institution (e.g., Barakat et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2018) or a rural area (Domènech-Abella et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018), being of the male gender (e.g., Hawkley et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2019), being older (> 75 years) (Yang et al., 2018) and having a low level of education (Savikko et al., 2005; Victor et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2018). Some of these variables, however, have shown a different role in loneliness. For example, in the studies by Theeke (2009), gender was not shown to be a predictor, and in those by Domènech-Abella et al., (2017) and O’Súilleabháin et al. (2019), it was women who reported more feelings of loneliness. Furthermore, in Theeke´s (2009) study, age was also not a predictor of loneliness feelings.

Cultural differences may explain gender and age disparities in the risk of late-life loneliness in different countries. In “familistic” and “collectivistic cultures” (Southern and Eastern European countries) are generally characterized by more ties within the family and community. In old age, these ties tend to reduce, and consequently, loneliness rises (Hansen & Slagsvold, 2016).

As mentioned above, one of the risk factors for loneliness is the loss of functionality. From a biopsychosocial perspective, functionality is understood as the individual’s physical ability to engage in ADLs within their context, taking into account their health condition. Thus, functionality results from the interaction between the health condition and the contextual factors involved (Direção-Geral da Saúde, 2004). Considering the consequences of functional disability itself, including social isolation (e.g., Guo et al., 2021) and depression (e.g., Burton et al., 2018), the relationship with loneliness is not surprising. However, functionality and loneliness could have an indirect relationship, and emotional regulation variables may mediate the relationship between the two phenomena. One of these variables seems to be affectivity. Affectivity, according to Watson et al. (1988), encompasses negative affect and positive affect. Negative affect is characterized by sadness and nostalgia and includes anger, guilt, nervousness, and fear. Functional limitations or loss can be assumed to increase negative affect, as this affect feeds aversion against adversity and threats (Gable et al., 2000; Schilling et al., 2016). Positive affect refers to enthusiasm, activity, and alertness (Watson et al., 1988). Loss of functionality can constrain the generation of positive affect by interfering with the behavioral repertoire needed to experience pleasure and reward (Gable et al., 2000; Schilling et al., 2016).

In turn, some research reported a predictive role for affectivity in loneliness. For example, Aanes et al.’s (2009) research with adults of various ages found that positive affect, along with interpersonal stress and social support, were substantial predictors of loneliness. Additionally, some studies have verified its mediating role. For example, affectivity mediated the relationship between physical health and loneliness in the study by Böger and Huxhold (2018). These authors verified this relationship in individuals between the ages of 40 and 84: those who had multiple health problems were shown to be more likely to experience negative affect and, consequently, greater loneliness.

Present Study

As it was seen, predictors of loneliness are functional dependence, a constellation of sociodemographic variables, depressive symptoms, and affectivity. Loneliness, in turn, impacts life quality in old age, involving emotional and physical consequences. These consequences show the relevance of studying loneliness in the elderly population, so we intend to confirm the correlates of loneliness in a sample of the elderly population, including functionality, emotional variables (depression and affectivity), and sociodemographic variables (residential context, age, gender, education, marital status, geographic location).

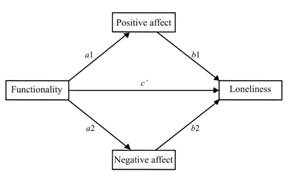

According to the literature, impaired functionality can lead to loneliness (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, 2018; Savikko et al., 2005). Also, impaired functionality can promote more negative affect (Gable et al., 2000; Schilling et al., 2016) and deplete positive affect (Gable et al., 2000; Schilling et al., 2016). In turn, affectivity could play an important role in loneliness (Aanes et al., 2009). Moreover, in particular, positive affect could function as a confrontation strategy to control emotions triggered in difficult circumstances (Watson et al., 1998). This evidence lays the foundation for the distinct potential importance of positive and negative affects as mediators of the relationship between functionality and loneliness. Thus, we tested a mediational theoretical model (Figure1) in which we hypothesized that functionality would have an indirect impact on loneliness through the effect on positive and negative affects, controlling for the potential role of the other variables.

Methods

Participants

Inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 65 years, Portuguese nationality, and sufficient physical and mental abilities to participate in the evaluations. Subjects with behavioral and cognitive problems and/or motor ability alterations that would make the assessment impossible or those with verbal refusal were excluded from the study. The resulting sample thus included 489 elderly people whose sociodemographic characterization is presented in Table 1. From this characterization, we highlight the higher number of residents in social care settings (SCS, nursing, and day-care homes), women, very older people (M = 80.18; DP = 7.05), with low or no education, widowers (60,1%) and from rural areas.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characterization and Comparison of UCLA-LS-16 scores by Sociodemographic Variables.

Note.N = 489. d = Cohen’s measure of sample effect size for comparing two sample means; UCLA-LS-16 = University of California Loneliness Scale; SCS = social care settings (nursing and day-care homes); η2 = ration between sum of squares between groups to total sum of squares.

***p < .001.

*p < .05.

Instruments

The Sociodemographic Questionnaire included the residential setting (SCS vs. community), gender, age, education, marital status (recoded as with and without a partner), and area of residence (urban, mixed or rural).

The University of California Loneliness Scale [UCLA-LS-16, original version by Russell et al. (1978) and Portuguese version by Pocinho et al. (2010)] assesses feelings of loneliness. In the Portuguese version, validated for the older population, the UCLA-LS-16 was composed of 16 items, answered on a four-point Likert scale, total score range between 16 e 64 points (more loneliness) and Cronbach’s alpha value of .91 (Pocinho et al., 2010). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

The Geriatric Functionality Scale [GFS; Espírito-Santo et al. (2014)] assesses the functional ability of older people (Cronbach’s alpha of .91). The scale consists of 20 dichotomized questions (No/Yes) regarding basic and instrumental activities of daily living. The rating was reversed so that the highest score (20 points) indicated a low level of functional disability. In our research, Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule-14 items [PANAS-14, original version by Watson et al. (1988), Portuguese version by Lemos et al. (2019)]. The Portuguese version measures subjective well-being and affectivity through seven items regarding the negative affect (α de Cronbach = .84) and seven concerning positive affect (α de Cronbach = .78), on a five-point Likert response scale, with a score ranging in each subscale between 7 and 35 points (highest level of affect) (Lemos et al., 2019). In the present study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 was verified for the positive affect subscale and .83 for the negative affect subscale.

The Geriatric Depression Scale - 8 items [GDS-8, original version by Yesavage et al. (1983); Portuguese version by Figueiredo-Duarte et al. (2021)] is an instrument that assesses depressive symptomato4logy through eight items, with two response options (Yes/No). The GDS-8 ranged from zero (no depressive symptoms) to eight points (high level of depressive symptoms) and had a Cronbach’s alpha of .87 (Figueiredo-Duarte et al., 2021). In our study, the GDS-8 showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .88.

Methodological Procedures

This cross-sectional research project is part of the Aging Trajectories Project of the Miguel Torga Institute of Higher Education (PTE-ISMT), approved by the Ethics Committee of the ISMT (DI&D-ISMT/2-2013), and the board of directors of each of 26 institutions in the central region of Portugal. Procedures derived from the PTE-ISMT (details in Daniel, Vicente, et al., 2015; Figueiredo-Duarte et al., 2019). Participants were informed about the objectives, methodologies, and conditions of participation, obtaining their written informed consent, and considering the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for the conduct of studies with human beings.

Analytical Procedures

Descriptive, comparative, and correlational analyses were performed with IBM SPSS (Version 26.0). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and frequencies) were used to characterize the sample. Comparing UCLA-LS-16 between the groups defined by sociodemographic variables was done using Student’s t-test for independent samples, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and respective effect sizes with Cohen’s d and eta-square. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination (r2) to assess the relationship between predictor (EFG), mediators (PA e NA), outcome variable (UCLA-LS-16), and covariates (GDS-8 and sociodemographic).

The mediational model was tested using the JASP software (version 0.16.1, JASP Team, 2020) due to its user-friendly interface, making it simple to assess indirect effects. Indirect effects were tested with bootstrapping (n = 10,000) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for the indices. We considered effects significantly different from zero (p < .05) if zero was excluded from the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval corrected for bias. For the magnitude of the mediational effect, we chose two measures of effect size, following Preacher and Kelley’s (2011) recommendations to produce a greater understanding of a given effect: 1) R2, which quantifies the portion of the variance in UCLA-LS-16 explained by the mediate effect; 2) the unstandardized indirect effect (ab), which is the expected indirect increase in UCLA-LS-16 across NA e PA for each unit change in GFS.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

The power analysis calculation (G*Power software; https://bit.ly/3FZArXO) revealed that we would have to have a sample size of more than 102 subjects to obtain a power greater than .80, detect medium effects (d = .50; f = .25; r = .30) and with an alpha of .05 for the respective statistical tests (t-test, ANOVA, and correlation). Furthermore, assuming a medium-size effect of GFS-8 on PA and a large effect of PA on UCLA-LS-16, it would be required sample size of 116 for .80 power (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007).

We assessed the normality of the distribution of scores in the variables under study using the Shapiro-Wilk test and the Skewness (Sk) and Kurtosis (Ku). The distribution of the scores of some of the variables proved to be skewed relative to the normal curve (Sk and Ku between -.31 e 4.22), and extreme values were verified in UCLA-LS-16, GFS, and GDS-8. For these reasons, these variables were transformed according to Templeton’s (2011) technique for data normalization.

Descriptive Statistics and Sociodemographic Comparisons

In Table 1, it can be seen that the UCLA-LS-16 scores were different depending on the residential status, gender, education, and marital status of the participants.

Correlations

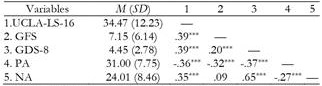

Pearson's correlation analysis (Table 2) showed that the UCLA-LS-16 moderately and positively correlated with GFS, GDS-8, and NA (r2 = 15.2%; r2 = 15.2%; r2 = 12.3%) and negatively correlated with PA (r2 = 13.0%).

Table 2. Descriptive and Pearson's Correlations between the Study Variables and Covariates.

Note.N = 489. GDS-8 = Geriatric Depression Scale – 8 items; GFS = Geriatric Functionality Scale; NA = negative affect of the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule– 14 items; PA = positive affect; UCLA-LS-16 = Loneliness Scale of the California University – 16 items.

***p < .001.

Mediational Analysis

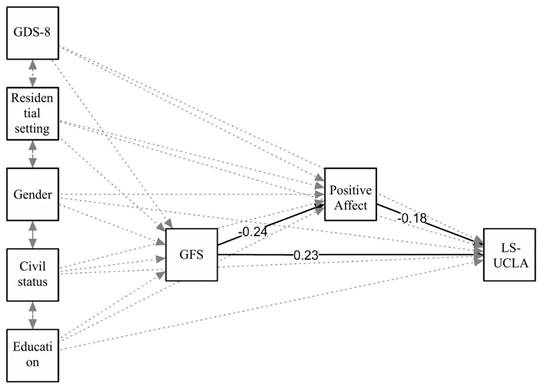

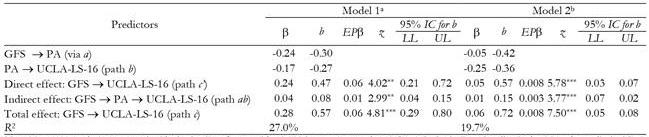

GFS did not prove to be a predictor of NA (b = .09; β = .09; EPβ = .05; t = 1.67; p = .97; 95%CI: -.02 to .19), so this variable could not enter the mediation model (Hayes, 2018). Thus, the model only integrated the PA as a mediator variable (Figure 2). Marital status was recategorized and dummy coded into “Without” (coded 0; n = 386; 78.9%) and “With partner” (coded 1; n = 103; 21.1%) to be included in the analyses. Other covariates were also dummy coded to be incorporated in the analyses (‘community’ and ‘women’ were coded 0; ‘SCS’ and ‘men’ were coded 1). As shown in Table 3, GFS had a positive and significant direct effect on UCLA-LS-16 scores, decreasing the total effect when positive affect was inserted as a mediator. That is, PA mediated the effect of GFS on UCLA-LS-16 after controlling for GDS-8, resident status, gender, education, and marital status, which supports the hypothesis of this study. However, this mediation was partial. The overall indirect effect of the functionality on feelings of loneliness through PA was significant. The global model accounted for 27.2% of UCLA-LS-16 variance.

Figure 2. Model of the Relationship between Functionality and Loneliness Mediated by Positive Affect.

Table 3. Testing the Mediating Effect of Positive Affect on the Relationship between Functioning and Loneliness.

Note.N = 489. Analysis computed with the JASP software with 10,000 bootstrap samples. GFS = Geriatric Functionality Scale; LL = lower limit; UL = Upper limit; PA = positive affect da Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule; UCLA-LS-16 = Loneliness Scale of the California University – 16 items.

aThe estimates were all calculated taking into account GDS-8 scores, residential setting, gender, education, and marital status.

bModel 2 does not include any covariate.

***p < .001.

**p < .01.

Given that the model does not make clear if the accounted variance in UCLA-LS-16 derives from the mediator and/or the covariates, we retested the mediation model without the covariates (Table 3). The indirect effect was still significant, but lower (ab =.01; R2 = 19.7%). Thus, the degree to which the functionality predicts loneliness through positive affect is higher after controlling for GDS-8, resident status, gender, education, and marital status.

Discussion

Empirical evidence suggests that functional disability is associated with loneliness in older people (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Hawkley & Kocherginsky, 2018; Macdonald et al., 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2019; Savikko et al., 2005; Warner et al., 2019). Additionally, affectivity may be a relevant mechanism in developing loneliness (Aanes et al., 2009; Böger & Huxhold, 2018). Therefore, this study explored the relationship between functionality, affectivity, and loneliness. Preliminarily, the relationships between loneliness and a variable set were verified.

Comparisons of Loneliness by Sociodemographic Variables

Consistent with another study (Barakat et al., 2019), SCS older people reported more loneliness, which may result from the fact that they are more functionally dependent, have depressive symptoms, poorer health status, and a greater number of medical conditions (Figueiredo-Duarte et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2018). Moreover, in our study, the SCS group included more widowers and rural residents than the community group, aspects that are also related to loneliness (e.g., Domènech-Abella et al., 2017; Dong & Chen, 2017; Savikko et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2018).

Older women in our study reported more feelings of loneliness than men, a result supported in some research (Domènech-Abella et al., 2017; Dong & Chen, 2017; O’Súilleabháin et al., 2019), but not in others (Hawkley et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2019). Cultural aspects of different cohorts may explain these discrepancies. For instance, in some cultures, women may express their feelings more, have a longer average life expectancy being widowed earlier (Aartsen & Jylhä, 2011; Tijhuis et al., 1999), or value interpersonal relationships more (Berg et al., 1981) than men.

Research shows that loneliness tends to increase in the oldest old (Aartsen & Jylhä, 2011; Qualter et al., 2015). Dong and Chen (2017) also found this relationship, but only in older women. However, we did not observe differences between age groups in our study, although an upward trend was observed. In the opposite direction, Victor et al. (2005) found that age was a protective factor, explainable by the hypothesis that individuals who live longer adjust better to the difficulties of advanced age. These discrepancies may reflect the specificity of the countries where the studies took place and the limits to generalizing the results.

As for marital status, the present findings join a fairly extensive literature on widowhood (e.g., Dong & Chen, 2017; Savikko et al., 2005; Victor et al., 2005). The loss of a close relationship in widowhood leads to a more significant impact than in the separated and divorced older person (Drennan et al., 2008). After mostly long-lasting marriages, it is common helplessness for fear of illnesses and uncertainty about the future, and both of these feelings contribute to activating loneliness in older people (López Doblas & Díaz Conde, 2018). Of note, those marital-history variations in loneliness are mediated mainly by social embeddedness features, partly in diverse ways for men and women (Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 2004), aspects not controlled in the present study.

Concerning educational attainment, as in other research (Savikko et al., 2005; Victor et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2018), we found that no or low education corresponds to more feelings of loneliness. Usually, individuals with a high level of education have a wider social network, which can influence feelings of loneliness (Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 1999).

Regarding geographical location, there were no statistically significant differences, which is in line with the study by Savikko et al. (2005). We would still expect that the migration of young people and consequent breakdown of small rural communities would be accompanied by higher levels of loneliness (Savikko et al., 2005). Other aspects not assessed (e.g., social networks, physical activity) may explain the absence of differences.

Correlations

Although it is not part of the objectives of this study, some of the correlations are worth discussing. The link functionality-loneliness, supported by other studies (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Hawkley & Kocherginsky, 2018; Macdonald et al., 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2019; Warner et al., 2019), strengthens the idea that functional disability reduces social contact and augments social isolation (Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 1999; Hajek & König, 2020). The loneliness link with depressive symptoms, following other studies (e.g., Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012; Lee et al., 2019; Peerenboom et al., 2015; Perissinotto et al., 2012; Tiikkainen & Heikkinen, 2005; Vicente et al., 2014; Victor et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2018), could stem from reduced energy or inability to maintain social relationships related to a declining mood (Tiikkainen & Heikkinen, 2005). The correlations of loneliness with negative and positive affect were also found by others (respectively, Böger & Huxhold, 2018; Stewart et al., 2001).

Considering the aforementioned empirical evidence and the statistical model constraints, we tested for the mediator effect of positive affect on the relationship between functionality and loneliness. However, we should discuss beforehand why negative affect is not predicted by functional disability. As some studies suggest, with age, emotion regulation tends to improve (Prakash et al., 2015), there is an increase in motivation to regulate emotions (Carstensen et al., 2003), a change toward disengagement strategies to regulate negative emotions (Scheibe et al., 2015), and a diminution in maladaptive strategies (Nolen-Hoeksema & Aldao, 2011; Prakash et al., 2015).

Mediation Model of Functionality, Positive Affect, and Loneliness

The results of the mediational analysis showed that current positive affect partially mediated the effects of functionality upon loneliness, controlling for depressive symptoms and relevant sociodemographic factors (residential setting, gender, marital status, education). To put it another way, functional disability predicted more loneliness through lower positive affect. Being functionally impaired is a problem conducive to social isolation, a decrease in personal networks, and less social attachment/integration (e.g., Aartsen & Jylhä, 2011; Tiikkainen & Heikkinen, 2005; Victor & Yang, 2012). On the other hand, people high in positive affect, by being more likely to seek social interaction and experience the interaction as pleasurable (Aanes et al., 2009), will tend to suffer less from the potentially detrimental effects of functional impairment. Depression and sociodemographic factors contributed to this mediational effect. This is in line with the literature describing the impact of these variables on loneliness (Barakat et al., 2019; Domènech-Abella et al., 2017; Dong & Chen, 2017; Lee et al., 2019; O’Súilleabháin et al., 2019; Savikko et al., 2005; Tiikkainen & Heikkinen, 2005; Victor et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018). Thus, our hypothesis was somewhat supported by our data and highlight the emotion regulation role of positive affectivity in the experience of loneliness.

These results suggest that older people with functional disabilities may experience less loneliness if the focus of the intervention is on positive affect, as in acceptance and commitment, mindfulness, and self-compassion therapies (Phillips & Ferguson, 2013; Shook et al., 2017), treatment for affective dimensions (Craske et al., 2019), dance-movement therapy (Koch et al., 2014), and intervention with support groups (Stewart et al., 2001). Interventions with older people with functional impairment should pay particular attention when they are females, widowed, with depressive symptoms, living in social care settings, and with a low level of education.

The mediating role of positive affectivity was only partial, which leads to the assumption that other regulatory mechanisms will be involved, such as self-esteem (Dahlberg & McKee, 2014) and coping mechanisms (Kharicha et al., 2018), which have been found to correlate with loneliness in old age.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations that should be considered for subsequent studies. Most importantly, the current cross-sectional study could not discriminate between the processes affecting functionality and loneliness or the possibility that functional impairment is caused by loneliness. Thus, while the results were robust to possible confounding variables, they cannot exclude the potential for reverse causality. However, as it has been shown, the reciprocal relationship between affect and loneliness seems to grow weaker with increasing age. Nevertheless, further research is required to elucidate the processes underlying the relationship between functionality and loneliness. Further, residual confounding from unmeasured latent variables could have played a role in functionality and loneliness. Therefore, additional work is needed to clarify the degree to which other emotional regulation mechanisms may contribute to the relationship between functionality and loneliness in older people. Other limitations comprise the non-randomized recruitment process, the voluntary participation, the self-assessment of functionality, the non-control of other independent risk factors (e.g., physical health symptoms, social network dimension, social relationships quality), and that this study did not assess simultaneous change in functionality and loneliness.

Conclusion

We found that functional disability predicts more loneliness. Furthermore, our results indicate that more functional older people have less loneliness due to positive affectivity, particularly if they are females, with symptoms of depression, living in social care settings, and with a low level of education. These findings emphasize that functional impairment may not only affect the efficacy of interventions designed to ease loneliness in older adults but that positive affectivity might also be a modifiable mechanism that can be targeted to increase well-being in the aged population.