Introduction

The existence of common factors through mental pathology, specifically in the case of the more prevalent mental health problems in the world, anxiety, and depression (Santomauro et al., 2021), has become an increasingly important research topic in mental health (Littlefield et al., 2021). However, the research on the common vulnerability between them is not new. In 1991, Clark and Watson developed a tripartite model of anxiety and depression, indicating that these disorders are both strongly associated with negative affective ties. They also identified two other specific factors: (1) positive affective and (2) physiological hyperarousal. Only depression was characterized by low positive affective rates (anhedonia), while hyperarousal was exclusively a characteristic of anxiety. Therefore, a part of the variance of the different disorders is shared (general distress). Even though this model was discovered three decades ago, this line of investigation continues nowadays with transdiagnostic models.

Transdiagnostic approaches seek to identify core psychological and biological processes that underlie multiple forms of psychopathology (Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). This approach can better explain the reality of mental disorders (e.g., comorbidity) and with greater ecological validity (Eaton, 2015). For this purpose, different researchers aimed to demonstrate the existence of such factors (Krueger & Eaton, 2015). In this line and continuing with the study of anxiety and depression, Hong and Cheung (2015) carried out a meta-analytic structural equation model to analyze the cognitive-specific vulnerability in depression (rumination, pessimistic inferential style, and dysfunctional attitudes) and anxiety (anxiety sensitivity, intolerance of uncertainty, and fear of negative evaluation). Their studies found moderate to strong correlations and that one-factor model fitted better to the data, suggesting an underlying common basis to both disorders. Biological correlates have also been found in people who suffer from these. Thus, some studies have shown biological transdiagnostic factors such as brain waves (Burkhouse et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2019) or weak inhibitory control and threat sensitivity (Venables et al., 2017). Although it may seem that the precipitants of these disorders are intrinsic characteristics of people, this is not always the case. As different researchers have shown, early-life adversity (Huh et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2019), stress (Conway et al., 2012), and exposure to traumatic events (Price & van Stolk-Cooke, 2015) also promote the risk of suffering emotional disorders. In this regard, the consideration of psychological, biological, and environmental factors can be helpful to improve interventions for mental disorders, making necessary an integrative conception that goes beyond individual factors and that also analyzes environmental factors that can affect the appearance of anxiety or depression, would be necessary. This change to integrative approximation is both conceptual - explaining why certain psychopharmacological agents and psychological therapies are effective in different conditions - and applied - providing a common target of intervention if the mechanisms underlying several disorders were found - (Krueger & Eaton, 2015).

Therefore, it can be said that another group of factors to take into account in mental health are the sociocultural ones. Clinicians and researchers agree on the importance of sociocultural factors in health. Bi-directional effects exist between health outcomes and these types of factors (Zvolensky & Leventhal, 2016). Although in other types of disorders, such as eating disorders, the impact of sociocultural factors has been more studied, the field of emotional disorders has yet to be investigated as much.

To our knowledge, there are previous reviews that examined risk factors focused on young people (e.g., Lynch et al., 2021), on a specific transdiagnostic variable (e.g., Rosser, 2019), or specific diagnoses (e.g., Zimmermann et al., 2020). However, there are still no systematic review studies that have jointly analyzed the environmental, biological, and psychological transdiagnostic risk factors in adults with anxiety or depressive disorders. A systematic review of the transdiagnostic risk factors related to anxiety or depressive disorders allows to:

Underscore the risk factors for developing anxiety or depressive disorders,

Provide recommendations for designing transdiagnostic measures that evaluate the risk, as well as the nature of anxiety or depressive disorders and

Highlight future directions for transdiagnostic therapy of both anxiety and depression.

Therefore, this systematic review aims to search for evidence on transdiagnostic risk factors for anxiety and depression in the clinical population diagnosed with these psychopathological conditions by analyzing the different types or categories of factors identified.

Method

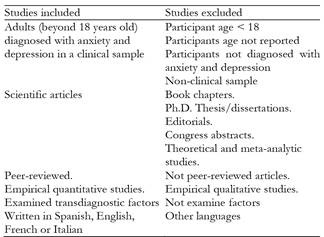

A systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) under number CRD42022370327. It was designed by the PRISMA-P guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols; Page et al., 2021) to identify studies that examined the risk factors for depressive and anxious emotional disorders. The eligibility criteria were developed using the Population Exposure Comparator Outcome (PECO) framework. Empirical studies were included if they met the following criteria:

Participants were adults (beyond 18 years old) diagnosed with anxiety and depression in a clinical sample.

They examined any transdiagnostic risk factors variable, such as psychological, biological, and sociocultural characteristics, and their association with the diagnosis.

Studies were not required to have a comparison group.

To ensure the quality of the empirical studies detected, they were required to be peer-reviewed.

Articles were excluded if the sample did not fit the intended group of participants or the studies did not report peer-reviewed, original empirical findings, such as reviews, opinion pieces, and conference abstracts. For inclusion, no constraints were placed on the publication date in this review. For a complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria for identifying relevant literature in this review, see Table 1.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Literature searches were performed in Scopus, Dialnet, and Web of Science (WoS: All databases, specifically WoS Core Collection, Current Contents Connect, Derwent Innovations Index, KCI Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, Russian Science Citation Index, and SciELO Citation Index). The following terms were entered into the database: "emotional disorder" OR "mood disorder" OR (anxiety AND depression) AND transdiagnostic AND "risk factor" OR predict* OR caus* OR vulnerab* OR predispos* OR susceptib* OR perfectionist OR rumination OR "negative affective" OR "anxiety sensitivity" OR "intolerance of uncertainty" OR neuroticism (see Appendix 1). Search strategies were adapted to each database (see Appendix 2). Hand-searching was used since research is supported by a hand-searching effort to complement database searches (Vassar et al., 2016). However, all the articles found with the manual search already appeared in the electronic search, so that no new ones could be included.

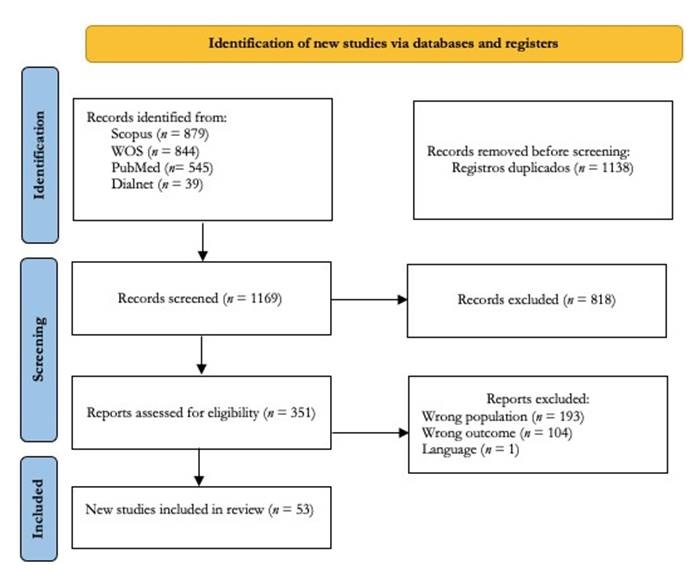

The last search was in December 2022, which yielded 2,307 studies, and 1,138 remained after removing duplicates. Search results were imported into Rayyan for screening (Ouzzani et al., 2016). After the removal of duplicates, all titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers. Disagreements at each screening stage were resolved through discussion between the two screening authors.

Data selection

Two independent reviewers with knowledge of the field assessed the study quality to reduce possible bias. The selection was performed in Rayyan based on the checklists from the Joanna Briggs Institute, explicitly using the Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies for cross-sectional studies and Checklist for Cohort Studies for longitudinal studies. These checklists are tools designed to help researchers and practitioners critically appraise different research studies. Once studies were selected, researchers used the JBI Checklist (Moola et al., 2020) to appraise each critically included study. The checklist consists of specific questions relevant to different study designs (e.g., cross-sectional studies). Researchers evaluated each checklist item individually, and at the end of the checklist is the final decision on whether to include it, not to include it, or whether additional information is needed. After developing each checklist individually, the two reviewers met and decided whether or not to include each item. When there was uncertainty about the interpretation, it was resolved by discussion between the authors based on the checklist items. Cohen's kappa (Cohen, 1968) was calculated to compare the degree of agreement among the reviewers. The minimum overall agreement score (Cohen's kappa) between the two raters was .88, and the conflicting results were discussed until 100% agreement was reached in the evaluated cases. Thus, the selection of the articles was carried out in two phases. In the first, the title and abstract were examined, obtaining a score of .91 on Cohen's kappa, and in the second, the full text of those studies that had passed the first screening was reviewed, obtaining a score of .88 on Cohen's kappa. On the other hand, to study the quality of the included studies, the method used by Hoppen and Chalder (2018) was followed, according to which the number of items rated 'yes' was summed and then divided by the number of the maximum possible number of 'yes' ratings and, to find the percentage, this amount is multiplied by 100.

Data extraction

At this stage, two reviewers independently obtained the information necessary to answer the research question posed in the study’s objective from the selected studies. The information collected in the data collection form is detailed in Tables 3-5. In addition, the risk factors of anxiety or depressive disorders were analyzed according to the type of risk factors: psychological, biological, or sociocultural risk factors.

Results

The literature search in this review comprised 53 articles from 2011 to 2022. For an overview of the study selection process, see Figure 1. The studies included are presented in Tables 3 to 5.

Studies details

The sample included women and men in 94.34% of the studies. However, three (n = 3, 5.66%) of the fifty-three articles exclusively used a women's sample (Dragan & Kowalski, 2020; Kircanski et al., 2015, 2016). Most of the publications (n = 52, 98.11%) were written in English, and only one (n = 1, 1.89%) of them was in Spanish (Toro-Tobar et al., 2020).

The studies have also been classified by type of design. In this sense, 20.75% of the studies analyzed (Boswell et al., 2013; Drost et al., 2014; Hijne et al., 2020; Hunt et al., 2022; Kircanski et al., 2015; Lukat et al., 2017; McEvoy & Erceg-Hurn, 2016; Spinhoven et al., 2014, 2018; Struijs et al., 2018; Swedlow et al., 2021) were longitudinal, therefore, the cross-sectional design predominated.

The overall quality of the included studies was high, with a mean rating of 91.91% across all studies. Longitudinal studies demonstrated slightly higher quality with an average score of 93.39%, compared to 91.52% for cross-sectional ones (see Tables 3 to 5). Separating the quality of the three main types of risk factors, the average quality of the psychological risk factors was 91.23% of the biological risk factors was 94.44%, and of the cultural risk factors was 93.86%.

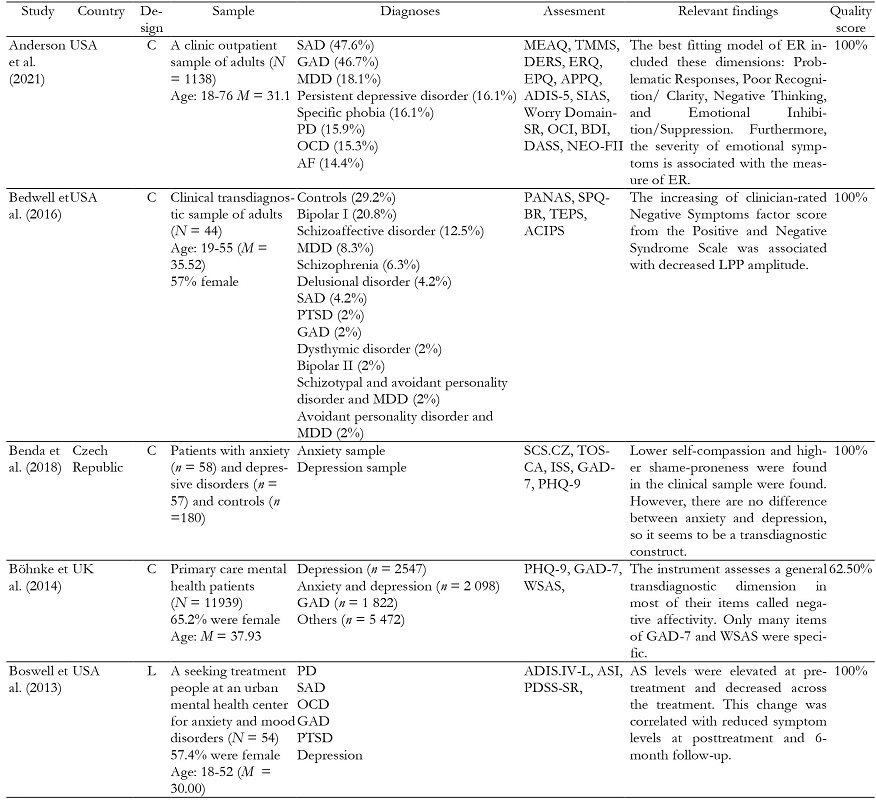

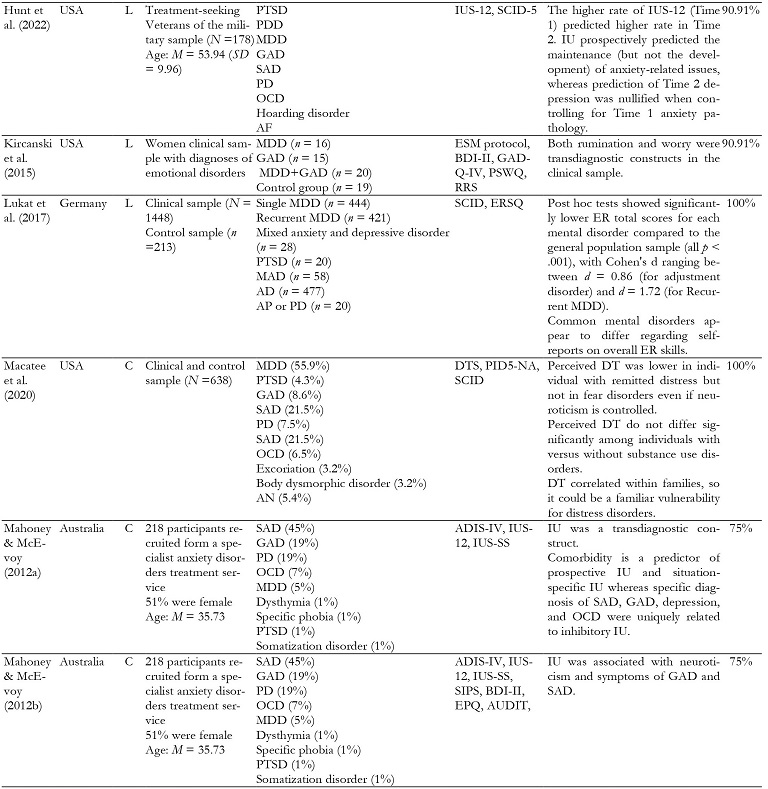

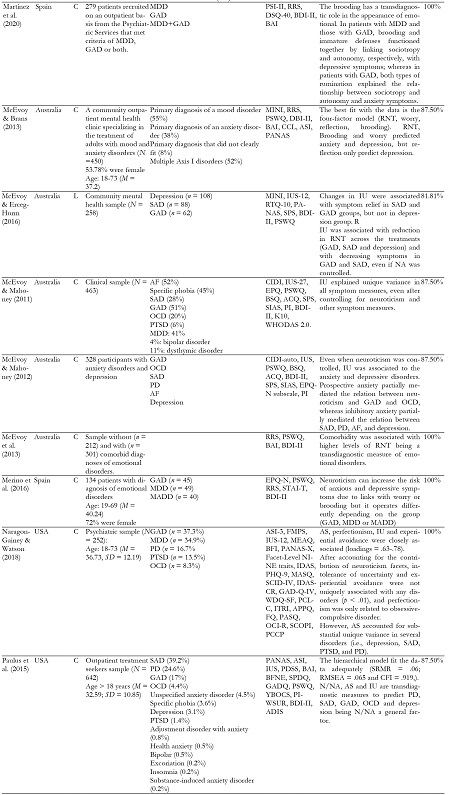

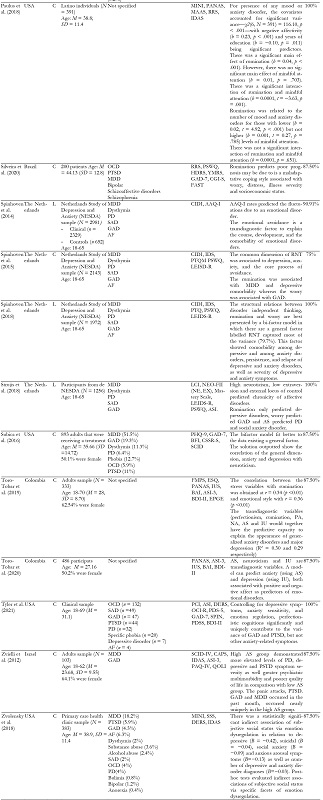

Table 3. (Cont.). Studies that evaluated the psychological risk factors (n = 39; 73.58 % of the studies).

Table 3. (Cont.). Studies that evaluated the psychological risk factors (n = 39; 73.58 % of the studies).

Table 3. (Cont.). Studies that evaluated the psychological risk factors (n = 39; 73.58 % of the studies).

Table 3. (Cont.). Studies that evaluated the psychological risk factors (n = 39; 73.58 % of the studies).

Note.AAQ = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; ACIPS = Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale;ACQ = Agoraphobic Cogni tions Questionnaire; ACS = Attentional Control Scale; AD = Adjustment Disorder; ADIS-5 = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5; ADIS-IV = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV; ALEQ-R = Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire; AP = agoraphobia; APPQ = Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire; AQ-50 = Autism Spectrum Questionnaire ; AS = Anxiety Sensitivity; ASI = Anxiety Sensitivity Inventory; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BFI = Big Factor Inventory; BFNE = Brief Fear Negative Evaluation Scale; BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; BSQ = Body Shape Questionnaire; C = cross-sectional study; CAARS = Conners` Adult ADHD Rating Scales; CAPS = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; CESD-10 = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; CGI-S = Clinical Global Impression-Scale, Severity of Illness; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DIVA = Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults; DSQ-40 = Defense Style Question naire; DT = Distress Tolerance; DTS = Distress Tolerance Scale; EPGE = Global Perceived Stress Scale; EPQ = Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; ER = Emotion Regulation; ERQ = Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; ERSQ = Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire; FAST = Short Functioning Test; FMPS = Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale; FQ = Fear Questionnaire; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; GADQ = Generalized; Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IDAS = Inventory of Depression Anxiety Symptoms; IDS = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; IDS-SR = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report: ISS = Injury Severi ty Score; ITRI = Iowa Traumatic Response Inventory; IU = Intolerance of uncertainly; IUS = Intolerance of Uncertainly Inventory; IUS-12 = Intolerance of Uncertainly Inventory Scale 12 items; IUS-SS = Intolerance of Uncertainly Inventory Self-Scale; L = longitudinal study; L1 CCM = Level 1 Cross Cutting Symptom Measure; L2 = Level 2 Cross Cutting Symptom Measure;; LCI = Life Chart Interview; LEIDS-R = Leiden Index of Depression Sensitivity Rumination Scale: MAAS. = Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale; MADD = Mixed Anxiety and Depressive Disorder; MASQ = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire; MDD = Mayor Depression Disorder; MEAQ = Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire; MEAQ = Multidimen sional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NEO-FFI = NEO Five-Factor Inventory; NIDA = Netherlands Interview of Diagnostic Autism-spectrum ; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; OCI = Obsessive Compulsive Inventory ; OCI-R = Ob sessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised; PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PAQ-IV = Personality Assessment Questionnaire-IV; PASQ = Panic Attack Symptom Questionnaire; PCCP = Personality Cognitions, Consciousness, and Perceptions Interview; PCI = Perfectionism Cognitions Invento ry; PCL-5 = Checklist for PTSD; PD = Panic Disorder; PDSS-SR = Panic Disorder Severity Scale- Self-Report; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PI = Padua Inventory; PI-WSUR = Padua Inventory–Washington State University Revision; PID-5 = Personality Inventory for DSM-5; PSI-II = Personal Style Inventory-II; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; PTQ = Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire; QFC =Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire; QOLI = Quality of Life Inventory; RNT = Repetitive Negative Thinking; RRS = Ruminative Responses Scale; RTQ-10 = Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire ; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview; SCID-5 = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5; SCOPI = Schedule of Obsessions, Compulsions and Pathological Impulses; SCS = Self-Compassion Scales; SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; SIPS = Social Interaction Phobia Scale; SPDQ = Social Phobia Diagnostic Questionnaire; SPIN = Social Phobia Inventory; SPQ-BR = Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire - Brief Revised; SPS = Suicide Probability Scale; SRET = Self-Referent Encoding Task; SSS = Sensation Seeking Scale; STAI-T = State-Trait Inventory ; TEPS = Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale; TOSCA = Test of Self-Conscious Affect; TTMS = Trait Meta-Mood Scale; WDQ SF = Worry Domains Questionnaire-Short Form; WSAS = Work and Social Functioning; YBOCS = Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale.

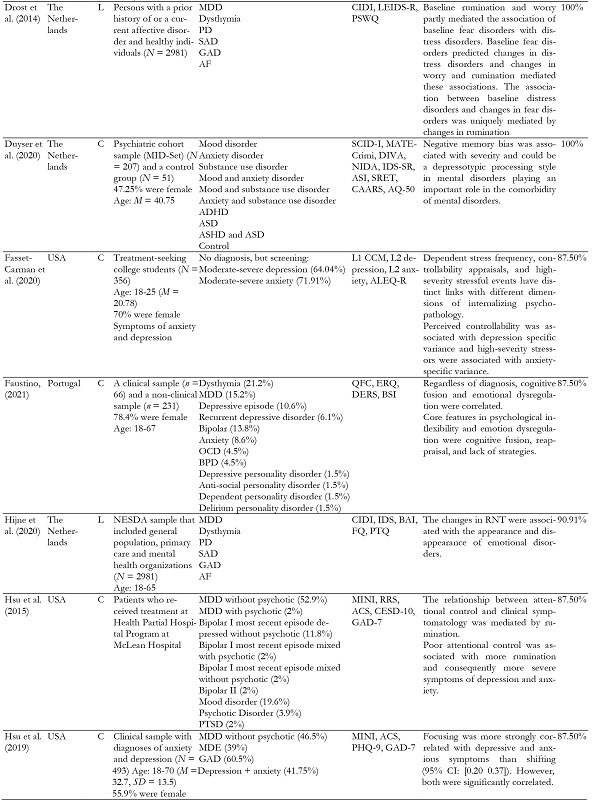

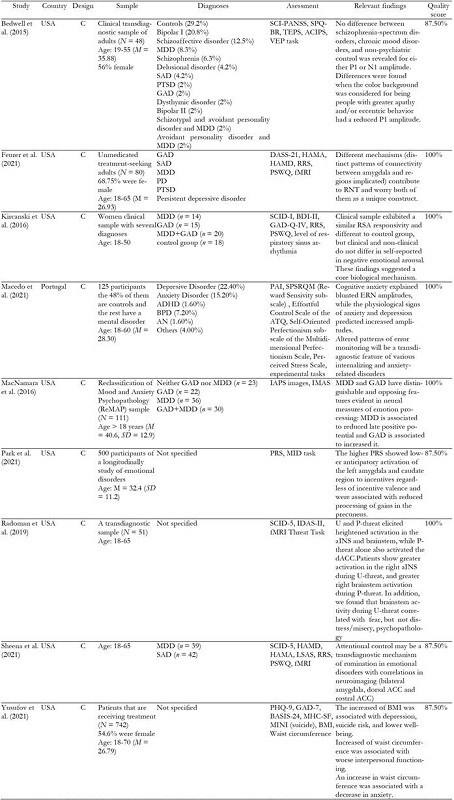

Table 4. Studies that evaluated the biological factors (n = 9; 16.98% of the studies).

Note.ACIPS = Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale; ATQ = Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire; BASIS-24 = Behavior and Symp tom Identification Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BMI = Body mass index; C = cross-sectional study; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; fMRI: Functional magnetic resonance imaging; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; GADQ = General ized; Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire; HAMA= Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAMD= Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IAPS = International Affec tive Picture System; IMAS = Interview for Mood and Anxiety Symptoms; L = longitudinal study; LSAS = Liebowitz's Social Anxiety Scale; MDD = Major Depression Disorder; MHC-SF = Mental Health Continuum Short Form; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PAI = Personality As sessment Inventory; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PRS = Polygenic Risk Scores; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire ; PTSD = Post traumatic Stress Disorder; RRS = Ruminative Responses Scale; RSA = Respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder; SCI-PANSS = Struc tured Clinical Interview for the PANSS; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview; SPQ-BR = Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire - Brief Revised; SPSRQ = Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5; TEPS = Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale.

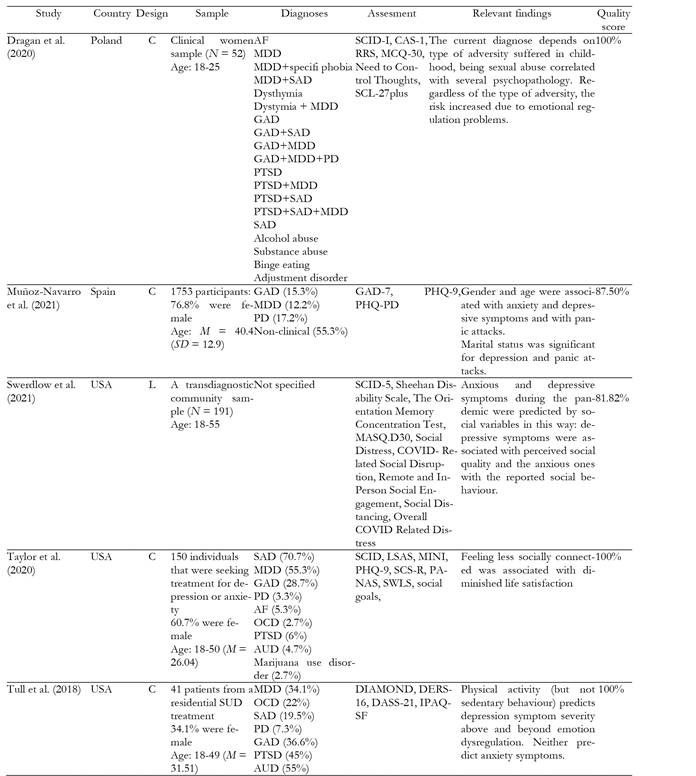

Table 5. Studies that evaluated the sociocultural risk factors (n = 5; 9.43 % of the studies).

Note.AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; C = cross-sectional study; CAS-1 = Cognitive-attentional syndrome; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; DERS -16= Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16 items; DIAMOND = Diagnostic Interview for Anxiety, Mood, and OCD and Related Neuropsychiatric Disorders; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; IPAQ-SF = International Physical Activity Questionnaire–Short Form; L = longitudinal study; LSAS = Liebowitz's Social Anxiety Scale; MASQ = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire; MCQ-30 = Metacognitions Questionnaire-30; MDD = Major De pression Disorder; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; PANAS = Positive and Negative Af fect Schedule; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PHQ-PD = Patient Health Questionnaire for Panic Disorder; PTDS = Posttraumatic Stress Disor der; RRS = Ruminative Responses Scale; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; SCID-5 = Structured Clinical In terview for DSM-5; SCL-27plus = Symptom Checklist-27-plus; SCS-R = Self-Compassion Scales-Revised; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale.

Type of risk factors

Psychological risk factors

Most studies (n = 39, 73.58%) examined psychological risk factors. To present the results in a structured way, they were grouped into six categories: cognitive processes, negative affect and neuroticism, intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety sensitivity, coping strategies, and other variables.

Cognitive processes were the most frequent category (n = 18, 33.96%). This data and the quality of the studies analyzed (mean quality score = 91.35%) allow us to affirm that they are a transdiagnostic risk factor. This category groups cognitive processes such as rumination, repetitive negative thinking, attentional control, and worry (Drost et al., 2014; Fassett-Carman et al., 2020; Hijne et al., 2020; Hsu et al., 2015, 2019; Kircanski et al., 2015; Martínez et al., 2020; McEvoy et al., 2013; McEvoy & Brans, 2013; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2011, 2012; Merino et al., 2016; Paulus et al., 2015, 2018; Silveira et al., 2020; Spinhoven et al., 2015, 2018; Struijs et al., 2018). The second category that has proven to be transdiagnostic the most has been neuroticism and negative affective rates (n = 14, 26.41%; mean quality score = 90.67%) (Bedwell et al., 2016; Böhnke et al., 2014; Macatee et al., 2020; Mahoney & McEvoy, 2012a; McEvoy & Erceg-Hurn, 2016; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2012; Merino et al., 2016; Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2018; Paulus et al., 2015, 2018; Struijs et al., 2018; Subica et al., 2016; Toro-Tobar et al., 2019, 2020).

Thirdly, intolerance of uncertainty also proved to be a transdiagnostic risk factor for anxiety and depression disorders by being reported in ten studies (Hunt et al., 2022; Mahoney & McEvoy, 2012a, 2012b; McEvoy & Erceg-Hurn, 2016; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2011, 2012; Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2018; Paulus et al., 2015; Toro-Tobar et al., 2019, 2020) with a high mean quality (84.77%). Fourthly, the role of anxiety sensitivity was found transdiagnostic in several studies (n = 6, 11.32%) (Boswell et al., 2013; Duyser et al., 2020; McEvoy & Brans, 2013; Paulus et al., 2015; Tyler et al., 2021; Zvielli et al., 2012) with a mean quality score of 93.75%

As for coping strategies, they were analyzed and found to be transdiagnostic in nine articles (16.98%), but not all examined the same strategies. Therefore, there is not enough evidence to allow us to state their transdiagnostic value so firmly. Thus, some of them (n = 5, 9.43%) focused the emotion regulation (Anderson et al., 2021; Faustino, 2021; Lukat et al., 2017; Tyler et al., 2021; Zvolensky et al., 2018) others (n = 3, 5.66%) examined the experiential avoidance coping (Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2018; Spinhoven et al., 2014, 2015) and only one (1.89%) analyzed and found the role of tolerance of distress in the appearance of anxiety and depressive disorders (Macatee et al., 2020). Finally, self-compassion, shame proneness, and internalized shame were also analyzed in one study (1.89%) (Benda et al., 2018), but further research would be necessary to establish a conclusion on whether it is a transdiagnostic risk factor for anxiety and depression.

Biological risk factors

Nine (16.98%) articles examined the cross-sectional biological risk factors, with high average quality. The amplitude of brain waves was confirmed in three (5.66%) articles (Bedwell et al., 2015; Macedo et al., 2021; MacNamara et al., 2016) and the activation of brain regions were examined in four (7.54%) (Feurer et al., 2021; Park et al., 2021; Radoman et al., 2019; Sheena et al., 2021) and demonstrated that was a transdiagnostic factor. Only one (1.89%) publication analyzed and found Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA) responsivity as a transdiagnostic measure (Kircanski et al., 2016), and the last one (Yusufov et al., 2021) associated the BMI with depression, suicide risk, and lower well-being. However, despite being the type of factors with the highest average quality, further study is needed to determine their transdiagnostic status.

Sociocultural risk factors

The less studied category was sociocultural risk factors (n = 5, 9.43%) publications. The low frequency of these studies also prevents us from drawing firm conclusions regarding their transdiagnostic status. This category is the most heterogeneous, and it groups childhood adversities (Dragan & Kowalski, 2020), gender, age, and marital status (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2021); the socialization process (Swerdlow et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2020) and physical activity (Tull et al., 2018). When people suffered childhood adversities, the risk of being diagnosed with anxiety or depressive disorders was higher than people who did not suffer from them (Dragan & Kowalski, 2020). In addition, being a woman, single (instead of being married), having lower studies (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2021), and being sedentary (Tull et al., 2018) are risk factors for anxiety or depressive disorders. The same study found that young adults (age 18-25) and adults (age 26-39) presented more anxiety or depressive disorders than older people. Moving on to the socialization process, feeling less socially connected was associated with diminished life satisfaction beyond clinical symptom severity (Taylor et al., 2020). Whereas depressive symptoms were related to perceived social quality, anxious ones were more tied to reported social behavior (Swerdlow et al., 2021).

Discussion

A systematic process outlined by the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021) was employed to identify all transdiagnostic risk factors for anxiety and depressive disorders in the clinical adult population. A variety of psychological, biological, and sociocultural factors emerged from the reviewed publications that appear to be transdiagnostically relevant in adults diagnosed with anxiety and depressive disorders. The results of this systematic review highlight various transdiagnostic factors that are markers of preventive or treatment interventions and promising future lines of investigation.

This review indicated that the most investigated transdiagnostic risk factors were psychological variables. Neuroticism or negative affectivity has shown its predictive power in the appearance of anxiety or depressive disorders, being a general factor in the transdiagnostic model (Paulus et al., 2015). It could represent the general distress shared in internalizing disorders. However, it works differently depending on whether it is a depressive disorder, an anxiety disorder, or a mixed (anxiety and depressive) disorder (Merino et al., 2016). These differences could be due to the links with cognitive processes such as rumination, repetitive negative thinking, attentional control, and worry that appear relevant in the development of anxiety and depressive disorders. Although they are cognitive processes, many studies have shown that ruminations are associated with depressive disorders (Hong & Cheung, 2015; Spinhoven et al., 2018; Strujis et al., 2018), whereas worry is a better predictor of general anxiety disorder (Spinhoven et al., 2015; Strujis et al., 2018). However, Kircanski et al. (2015) have shown that they both are transdiagnostic constructs between anxiety and depressive disorders. Thus, due to the correlation of these variables (Silveira et al., 2020), it could be integrated into a transdiagnostic dimension, such as repetitive negative thinking (Spinhoven et al., 2015; 2018). Moving on to other cognitive variables, focusing (Hunt et al., 2022) and reflection (McEvoy & Brand, 2013) could be better predictors of depressive disorders.

The second and third most studied transdiagnostic variables were intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety sensitivity. Although the meta-analytic structural equation model carried out by Hong and Cheung (2015) found anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as anxiety-specific vulnerability, in this review it has been found that such variables are transdiagnostic and, therefore, would correspond to a shared vulnerability between the diagnoses of anxiety and depression (Paulus et al., 2015; Toro-Tobar et al., 2019; 2020) even after controlling for neuroticism (McEvoy & Mahoney, 2011; 2012 Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2016). This result aligns with previous investigations where this construct was essential to the genesis of internalizing disorders (Griffith et al., 2010), among which are the disorders studied in this systematic review (Krueger & Eaton, 2015). It would be essential to investigate other transdiagnostic variables with less evidence, such as emotional regulation or experiential avoidance, which could explain the efficacy of the same treatment for anxious and depressive disorders and the development of transdiagnostic protocols as an effective and more efficient treatment alternative (Aguilera-Martín et al., 2022).

The second type of variable most investigated according to this review was biological ones, where the studies' average quality was excellent (94.44%). However, more research would be needed to have more empirical evidence. All biological studies are cross-sectional, so longitudinal studies could also help gain empirical weight. The typical way to examine the biological correlate is to evaluate the neurobiological waves or activation regions. The amplitude of waves or the amygdala activation was a transdiagnostic biological finding. However, other measures, such as RSA, BMI and waist circumference, require more investigation because there was only one article for each measure. Although these factors have been investigated more than sociocultural factors, epigenetics has demonstrated how the environment can produce changes in our body, which can affect mental health (Cecil et al., 2022). Thus, it has been shown how situations of severe stress produce changes in brain waves (Jin et al., 2021) or how child abuse produces structural, biochemical, and functional changes in the brain (Coley et al., 2021; Glaser, 2000); therefore, studies should also evaluate contextual dimensions that can promote these brain changes.

Among the factors investigated by studies in the present review, some underexplored factors warrant further investigation. Sociocultural were the less investigated. There are only four publications, and all the categories except the process of socialization, which was investigated twice, have only been investigated in one publication. In addition, this systematic review does not show positive results for emotional regulation, cognitive biases, or metacognition. It could be due to the studies that investigate these variables not using the inclusion variables that this systematic review has analyzed.

This systematic review also has limitations to be taken into account. It is important to note that the results of this review should be interpreted with caution due to several methodological complexities and uncertainties. First, the studies varied considerably in terms of transdiagnostic measures, and many of them were in self-report format, so despite having found considerable consistency in some factors, the diversity in the measures of psychopathology included in the studies makes it difficult to draw unified conclusions.

Secondly, it is essential to consider that approximately 80% of the studies analyzed are cross-sectional and that almost half of them were conducted in the United States, which makes it difficult to determine causality and generalization of the results obtained. On the other hand, the inclusion criteria applied in this review meant that only peer-reviewed publications were used. Although this measure has been taken to guarantee the quality of the studies, bias may occur due to the file drawer problem.

Furthermore, future lines of investigation could focus on the study of those less investigated variables, for example, sociocultural factors, to obtain more excellent scientific evidence regarding the common factors of the different diagnoses. On the other hand, future studies could make an empirical model that can explain the standard part of anxiety and depressive disorders that could be attributed to transdiagnostic variables and specific variance that could differentiate between the specific disorders. These findings can also be extrapolated to improve assessments of anxiety or depressive disorders in adults through the need for dimensional assessments that take into account multiple constructs, such as the Multidimensional Emotional Disorders Inventory (MEDI) (Osma et al., 2021; Rosellini & Brown, 2019) or the need of use transdiagnostic interventions, such as the Unified Protocol (Barlow et al., 2018) to intervene on the vulnerability and maintenance mechanisms shared by all emotional disorders. In addition, the intervention in transdiagnostic variables can be more efficient since it allows its application in group treatment format and can be used in several diagnoses (Aguilera-Martín et al., 2022; Peris-Baquero et al., 2022). Finally, integrated and multidisciplinary interventions will also have to be investigated and carried out to reduce the symptomatology of people suffering from anxiety or depressive disorders and improve their quality of life.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of transdiagnostic risk in patients diagnosed with anxiety or depressive disorders in adult samples. After reviewing several risk factors in high-quality studies, it cannot be stated with certainty that all of them are transdiagnostic risk factors for anxiety or depressive disorders. While some psychological factors such as cognitive processes, neuroticism, negative affective rates, intolerance of uncertainty, and anxiety sensitivity have demonstrated their transdiagnostic nature, the remaining variables need further investigation to reach a solid conclusion. Another significant result was the most relevant predictors in each disorder. Thus, it was intolerance to uncertainty for generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and major depressive disorder, as well as anxiety sensitivity for panic disorder. In the case of posttraumatic stress disorder, both anxiety sensitivity and intolerance to uncertainty were the best variables. On the other hand, despite the transdiagnostic model advocated in this paper, an attempt has been made to synthesize which variables have been the most investigated for each disorder to guide future research.

These findings have important implications for prevention and intervention. Improving emotion regulation and self-regulation and reducing environmental conditions that foster stressful life events may be particularly salient targets for the prevention and intervention of general and specific dimensions of psychopathology. In addition, this publication allows a stronger foundation of knowledge for how to build a model for anxiety or depressive disorders using transdiagnostic and specific risk factors that could help to understand the development of psychopathology and how to prevent it. In addition, this review identified several methodological concerns that should be addressed in future research. In particular, there is a fundamental need for more comprehensive, longitudinal, and multidisciplinary studies to establish further causal relationships. Conducting such studies could result in a more substantial knowledge base that will drive the identification of robust relationships between transdiagnostic risk and mental disorders, which can facilitate the development of empirically supported approaches to prevention and intervention.

texto en

texto en