Introduction

According to Dukes et al. (2021), it seems reasonable to assume that having overcome the presumed protagonist of behaviourism and cognitivism, we have now entered an affective era, given that most psychological research is integrating into its explanatory and predictive models of human behaviour affective variables, such as: moods; emotions; or emotional intelligence (EI). In line with this apparent emotional zeitgeist, numerous studies in educational psychology are experiencing a shift in terms of attention towards the affective sphere (e.g., Cejudo et al., 2016; Peláez-Fernández et al., 2022; Uitto et al., 2015). In fact, there has been an increase in research into the influence of emotional processing on teacher’s professional performance in the last decade (e.g., Cejudo & López-Delgado, 2017; Chen & Cheng, 2022; Martínez-Saura et al., 2022; Uitto et al., 2015).

Teachers constantly experience emotional demands from families, colleagues and students (Hargreaves, 1998; Schutz, 2014; Yin et al., 2019), and their own emotions influence how they respond to these, and their own behaviour (Hagenauer & Volet, 2014). These responses in turn have an impact on the teaching quality (Hosotani & Imai-Matsumura, 2011) and they also affect student learning (Ronfeldt et al., 2013). In addition, there is abundant research indicating that emotions also affect job satisfaction and a teacher’s professional development (Chen et al., 2020; Mérida-López et al., 2020; Schutz, 2014). Thus, emotions may be closely associated with job satisfaction if they are mainly of a positive hedonic tone (pleasant), or they may be related to a risk of burnout if they are mostly of a negative hedonic tone (unpleasant) (King & Chen, 2019; Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017; Schutz, 2014). In this sense, there is considerable concern regarding the emotional burnout of teachers due to the educational and socioeconomic consequences of this (Dicke et al., 2018).

Teachers who are less competent in recognizing and regulating their emotions appear to more negatively interpret their environment and their perception of self-efficacy, and hence, they may feel maladapted to the educational system (Castillo-Gualda et al., 2017). Recent studies demonstrated that positive emotional attitudes like engagement predict relevant outcomes such as teacher efficacy, satisfaction and well-being (Mérida-López et al., 2020).

Among the studies into education and emotions, the contributions of Schutz and Pekrun (2007) stand out. In fact, except for the pioneering work of Hargreaves (1998; 2001), the publication of the manual Emotion in Education can perhaps be considered a milestone in this field (Schutz & Pekrun, 2007). The subsequent manual produced by Schutz and Zembylas (2009) represents a second milestone, after which the handbook focusing on the role of emotions in learning was published by Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2014), as well as an article that centres on teacher’s emotions (Schutz, 2014). Interest in this field was further consolidated in the following year with the publication of a prominent review article (Uitto et al., 2015). It should be noted that no theoretical framework integrates all aspects of this field beyond the work of Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia (2014) and those that focus on EI (e.g., Petrides & Furnham, 2001). Concretely, Petrides & Furnham (2001) define EI as a "personality trait" that involves a gamut of emotional self-perceptions located within the lower echelons of personality hierarchies. In this sense, EI is a variable personality trait that conditions the experiences of different affective states (frequency and intensity) and as such, these studies may provide an integrating theoretical framework for many aspects of these emotional aspects of teaching, reviewed by Uitto et al. (2015). Some meta-analyses have confirmed the positive relationship between EI and well-being in adults (Sánchez-Álvarez et al., 2015) and similarly, some studies confirm the positive relationships between EI and engagement, as well as the negative relationships with burnout (Xing, 2022).

To date, considerable quantitative empirical research has focused on mood states (positive or negative affectivity) and on the emotional status of teachers, such as engagement, stress or burnout, or on EI. However, quantitative empirical research on discrete teacher emotions remains scarce (Frenzel et al., 2014). Indeed, most of these studies have been largely qualitative, based largely on the use of semi-structured interviews (e.g., Hargreaves, 2001; Schutz et al., 2020).

A range of scales are available to assess mood states (e.g., PANAS) and discrete emotions (e.g., POMS) in psychological research, although these instruments are not contextualized to the teaching environment. However, a teacher’s emotions are not isolated within the individual but they are influenced by their environment, they involve person-environment interactions, they exist in a socio-historical context and they involve dynamic transactions that occur in relations to specific emotional episodes within the school microsystem (e.g., Hargreaves, 2001; King & Chen, 2019). Therefore, it is not so much a matter of assessing if a teacher feels nervous in general or when faced with the need to resolve a conflict in the classroom, nor is it a matter of defining if the teacher’s mood is generally good but rather, it is necessary to determine if these are common reactions to their students. In other words, the assessment of a teacher’s specific emotions requires focusing on the emotions "experienced" in the context of teaching.

In 2016, two self-report scales were published that could help offset the qualitative preponderance when studying the emotions of teachers. The first was the Teachers Emotions Scale (TES; Frenzel et al., 2016), which has 12 items aimed at assessing three discrete emotions in teachers: enjoyment, anger, and anxiety. By contrast, the Teacher Emotion Inventory (TEI; Chen, 2016) has 26 items that address five discrete emotions in teachers: enjoyment, anger, fear, love, and sadness. The current study is focused on the brief Spanish version (TEI-BSV).

The purpose of the research was to adapt and validate the TEI questionnaire (Chen, 2016) to the Spanish-speaking context. The specific aims of this study were: (1) to test the factorial validity and internal consistency of the instrument (TEI-BSV); (2) to explore the correlations between the TEI-BSV, and the affective and cognitive components of subjective well-being, as evidence of convergent validity; (3) to test the predictive power of the TEI-BSV for burnout and engagement as evidence of validity; and (4) to examine the incremental validity of the TEI-BSV on the variables burnout and engagement, over and above the predictive power of EI.

Consequently, the following hypotheses were postulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The TEI-BSV will exhibit the original factor structure of five factors correlated into two groups of positive and negative emotions.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The scales of the TEI-BSV will show adequate internal consistency.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The TEI-BSV will show convergent validity with both the hedonic or affective component, as well as with the cognitive or evaluative component of subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): The TEI-BSV will exhibit criterion validity in predicting burnout and engagement.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): The TEI-BSV will exhibit incremental validity in predicting burnout and engagement relative to the EI trait as a rival predictor.

Methods

Participants

The study was carried out on a sample of 567 teachers from public and subsidized schools in Castilla-La Mancha (CLM) who worked in different stages of the education system: Early Childhood Education (ECE), Primary Education (PE), and Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE). The participants were selected by non-probabilistic sampling of an incidental or accessibility type. Among the participants, 280 teachers (49.7%) worked in an urban context within CLM (>10,000 inhabitants) and 283 teachers (50.3%) in a rural context (<10,000 inhabitants). The sample was distributed among state schools (549 teachers; 96.8%) and subsidized schools (18 teachers; 3.2%). In terms of the stage of education, 71 teachers work in ECE (12.4%), 241 in PE (42.5%) and 256 in CSE (45.1%). The experience of the teaching staff ranged from 5 years (61 teachers; 11.6%), to between 6 and 15 years (114 teachers, 21.7%) and >15 years (351 teachers; 66.7%). In terms of sex, 371 of the teachers were women (65.5%) and 196 men (34.5%). Finally, the age of the participants ranged from 25 to 65 years old (M = 46.04; SD = 9.09).

Instruments

Teacher Emotion Inventory (TEI; Chen, 2016). This scale assesses the emotions experienced by teachers in the teaching/learning environment. It consists of 26 items distributed into five dimensions: two dimensions related to positive emotions (joy and love) and three dimensions related to negative emotions (sadness, anger and fear). Responses are provided using a 6-point Likert-type scale, where 1 is "never" and 6 is "almost always", and it is a scale proven to have adequate validity and reliability (Chen, 2016): joy (α = .90), love (α =.73), sadness (α =.86), anger (α =.87) and fear (α =.86).

Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988; adapted to Spanish by Sandín, 2003). This scale evaluates positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA), constituting an indicator of the affective component of subjective well-being. It consists of 20 items assessed on a 5-point Likert-type scale, where 1 is "very little or not at all" and 5 is "always or almost always". There is evidence that PANAS has adequate factorial validity and reliability (Sandín, 2003): (α = .73) for PA and (α =.74) for NA. The reliability of this instrument in the present study was (α = .84) for PA and (α = .86) for NA.

Satisfaction With Life Scale(SWLS; Diener et al., 1985; adapted to Spanish by Atienza et al., 2000). This scale evaluates the cognitive component of subjective well-being. It is composed of 5 items that are scored on a Likert-type scale in which 1 is "strongly disagree" and 5 is "strongly agree". The evidence shows SWLS has an adequate structural validity and reliability (α = .87: Diener et al., 1985). The reliability of this instrument in the present study was α = .85.

Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form (TEIQue-SF; Petrides & Furnham, 2003; adapted to Spanish by Pérez, 2003). This questionnaire assesses EI as a trait and it is composed of 30 items, the responses to which are collected through a 7-point Likert-type scale where 1 is "completely disagree" and 7 is "completely agree. The TEIQue-SF has evidence of adequate factorial validity and reliability (α = .88) (Petrides & Furnham, 2003). The reliability of this instrument, in the current study, was α = .85.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach & Jackson, 1986; the Spanish version of Seisdedos, 1997 was used). This instrument evaluates the syndrome of being burned out at work. It is composed of 22 items that are divided among three dimensions: burnout, depersonalization and self-fulfilment. A 6-point Likert-type scale is used to score each item, where 0 equals "never" and 6 equals "every day". There is evidence of adequate factorial validity and reliability of the MBI: emotional exhaustion (α = .90), depersonalization (α = .79) and personal fulfilment (α = .71) (Maslach & Jackson, 1986). The reliability of this scale in the present study was (α = .83) in personal fulfilment, (α = .63) in depersonalization and (α = .84) in exhaustion.

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli et al., 2006; the Spanish version by Salanova & Schaufeli, 2000 was used). This scale is used to assess work engagement and it is comprised of 17 items divided among three factors: vigour, dedication and absorption. The responses are collected using a 7-point Likert-type scale where 0 is "never" and 6 is "always", and the UWES has adequate structural validity and reliability: vigour (α = .82), dedication (α =.89) and absorption (α =.83) (Schaufeli et al., 2006). The reliability of this scale in the present study was α = .83 for vigour, α = .84 for dedication and α = .76 for absorption.

Procedures

The validation of the TEI-BSV was first carried out in accordance with the guidelines for instrument adaptation (Zenisky & Hambleton, 2012). As such, a Spanish translation was obtained from a native English speaker fluent in Spanish and this was then back translated by another freelance translator. Finally, the original and translated items were analysed, and the final content of the instrument was agreed upon by the authors.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Social Research at the University of Castilla-La Mancha (CEIS-646208-H2X8), within the framework of a national research project (PID2020-115624RA-I00). It also complied to the international ethical criteria laid out in the Helsinki Declaration. Appropriate measures were taken to ensure complete confidentiality of the participants' personal data, in accordance with the Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5th on Personal Data Protection and the guarantee of digital rights.

Finally, once the content of the TEI-BSV had been defined and agreed upon, the management teams at each of the centres was contacted, and the instruments were administered on paper in a confidential manner. Informed consent was provided by the teaching staff prior to completing the questionnaires.

Data Analysis

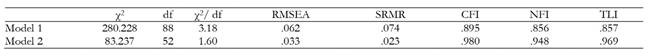

All the statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS Statistical Package (IBM, 2016). To analyse the internal structure of the TEI-BSV, a cross-validation strategy was employed having divided the sample into two random groups. In the first sample (n = 200), an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed and given that certain relationships between the resulting factors was assumed, an oblique rotation was chosen in accordance with earlier recommendations (Kline, 1994). For this, the Promax rotation method was used and with a value of k = 3, in accordance with the indications of Hendrickson & White (1964). The rest of the sample (n = 367) was subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) performed with AMOS 22 and using the maximum likelihood method. Model fit was tested with the χ2/df, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), normalised root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation index (RMSEA), with values of χ2/df < 5.0; those of CFI and TLI > .90; and SRMR and RMSEA < .05, indicating a good fit (Kline, 2015).

To determine the internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha (α) was calculated. A Pearson correlation was used to analyse the evidence of convergent validity, with the relationship of each subscale with subjective indicators of well-being in the cognitive and affective component, and with EI, studied. To obtain evidence of criterion validity, the relationship of each of the subscales with indicators of burnout, engagement and life satisfaction was analysed by multiple regression. Finally, to obtain evidence of incremental validity, hierarchical multiple regressions were used to examine whether the adapted scale added predictive power (variance explained) to that previously expected in order to show EI as the sole predictor of burnout or engagement.

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

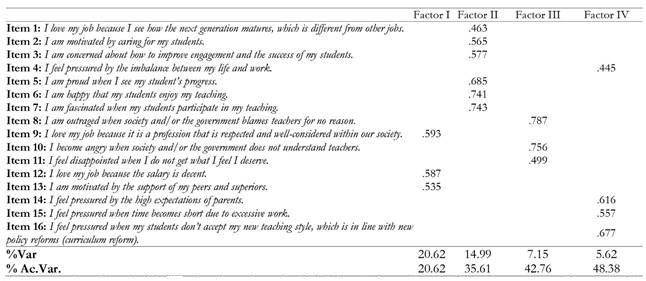

From the data obtained, we first calculated the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index (.84) and applied Bartlett's test of sphericity [χ2 (253) = 3101.9; p < .001]. After parallel analysis of the polychoric correlation matrix, the appropriate number of factors to be extracted was estimated to be four. The factor analysis derived from the factor solution revealed that this four-factor structure explained 48.38% of the total variance of the questionnaire. It was decided to remove the smallest factor loadings (< .40) and items that presented factor loadings associated with two or more factors (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), such that the results of the EFA defined four factors with the following structure (see Table 1):

Factor 1 (Love or affiliation): represented by items 9, 12 and 13. This factor is described as implication in the teaching profession and caring for the students.

Factor 2 (Happiness or enjoyment): represented by items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7. This factor reflects the joy felt by teachers through their positive interactions with students, colleagues and administrators.

Factor 3 (Anger or indignation): represented by items 8, 10 and 11. This factor is described as the anger felt by teachers at being treated unfairly by society and the pressure imposed by the bureaucracy surrounding education.

Factor 4 (Fear or stress): represented by items 4, 14, 15 and 16. This factor represents the fear related to student problems, excessive family expectations, and family and work conciliation.

Table 1. CFA factor loadings for the TEI-BSV scores in the first sample (n = 200). Configuration matrix.

Note.These results are the result of a CFA performed according to the principal axis extraction method and the Promax-type oblique rotation method with k = 3; Items with a factor loading <.40 and items with factor loadings on two or more factors were omitted; Factor I: Love; Factor II: Happiness; Factor III: Anger; Factor IV: Fear.

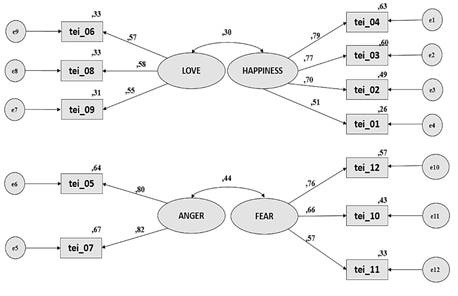

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

We performed a CFA on the second sample (n = 367), although the first model did not show a good fit (Table 2). Subsequently, items 1, 3, 4 and 11 were eliminated as these presented correlations below .40 with their factor. As a result, a good fit of the factor structure model was obtained (see Table 2). The objective factor loadings of the items ranged from .51 to .82 and all were statistically significant (see Figure 1).

Reliability and Associations among the TEI-BSV subscales

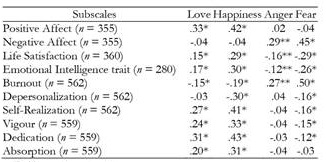

The subscales showed satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach's α ranging from .79 to .68 (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations between the different subscales of the TEI-BSV: descriptive statistics and internal consistency.

Note. *p < .05;.

**p < .001.

The correlations between the love and happiness subscale scores were positive, as were the correlations between the scores in the anger and fear subscales. It is noteworthy that there were no significant relationships between the subscales representing PA (love and happiness) and the subscales representing NA (anger and fear).

Evidence of Convergent Validity

In the first place, the love and happiness factor scores were positively correlated with PA (Table 4), while anger and fear factor scores were positively correlated with NA. Moreover, love and happiness correlated positively with life satisfaction, while anger and fear correlated negatively with this factor. The EI trait correlated positively with love and happiness, and negatively with anger and fear.

Evidence of Criterial Validity

Firstly, the absence of multicollinearity problems was tested (tolerance values < .20; VIF > 4.00).

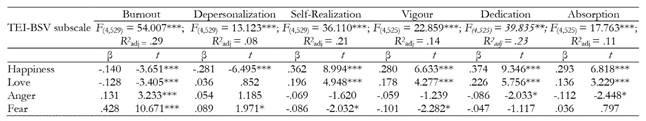

For each of the multiple regression analyses (Table 5), the TEI-BSV subscales were used as predictor variables, while the scores in the burnout and the engagement subscales were used as criterion variables. Accordingly, the TEI-BSV explained between 8-29% of the variance in burnout and between 11-23% of the variance in engagement.

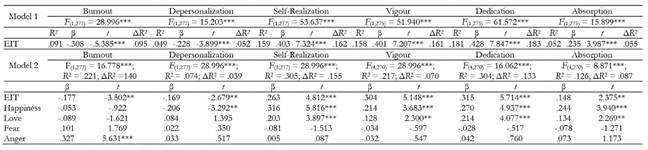

Evidence of Incremental Validity

First, we again ensured the absence of multicollinearity problems (tolerance values < .20; VIF > 4.00). From the results of the hierarchical regressions (Table 6), Model 1 shows the predictive power of the EI trait with respect to the burnout and engagement scales, which was significant in all cases. In this model, using the EI trait as the only predictor explained between 5-16% of the variance for burnout, and between 5-18% of the variance for engagement. Subsequently, Model 2 in the aforementioned table presents the results of adding the four TEI-BSV scales as additional predictor variables to the multiple regression model along with the EI trait. With this set of five predictors (i.e., the overall TEIQue-SF score plus the four TEI-BSV scores), more of the variance in the six regressions was explained, with the variance of burnout explained rising to the range of 7-31%, and that of engagement rising to 13-30%.

In Model 2 for burnout as a criterion variable, among the scales of the TEI-BSV, only anger was shown to be a significant predictor of burnout. Likewise, only happiness was a significant predictor of depersonalization. Finally, both happiness and love are shown to be significant predictors of self-fulfilment in the presence of the EI trait as a rival predictor.

In Model 2 for engagement as a criterion variable, among the TEI-BSV scales, both happiness and love were significant predictors of vigour, dedication and absorption in the presence of trait EI as a rival predictor.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to adapt the TEI questionnaire (Chen, 2016) to a Spanish-speaking context and to study its internal consistency and the evidence of factorial, convergent, criterion and incremental validity. As a result, an abridged version of of the TEI in Spanish was prepared, with 12 items, for which sufficient evidence of structural validity, reliability, convergent validity, criterion validity and incremental validity was obtained.

Regarding factorial validity, the results of the EFA and CFA did not corroborate the original factor structure of the TEI (Chen, 2016) when applied in an abridged form to Spanish teachers. The EFA and the CFA showed that the TEI-BSV has a four-factor structure, with these four factors grouped in pairs according to their interrelationships: a pair of positive emotions (love and happiness) and another pair of negative emotions (anger and fear). Indeed, these pairings are consistent with Watson & Tellegen's classic model of affect (1985). Positive and moderate relationships were evident between the subscales assessing love and happiness, and between the anger and fear subscales. Importantly, the love and joy subscales are not significantly related to the anger and fear subscales, which might reinforce the idea of the bifactor model of affect (PA and NA). Watson & Tellegen (1985) indicated that these two factors do not represent polar opposites or dimensions with negative correlations between them but rather, they actually constitute two independent and uncorrelated dimensions of affect.

The results regarding the factorial structure diverge from those presented previously (Chen, 2016) and they may reflect slight cultural differences in the meanings attributed to adjectives that refer to mood states (Quirin et al., 2018). Indeed, differences between Eastern and Western populations have been confirmed, with subtle cultural differences in the processing of emotional information (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2005) and in emotional regulation strategies (Butler et al., 2007; Nozaki, 2018). Nevertheless, another reason to explain the discrepancy between our 4-factor structure and Chen's (2016) 5-factor structure is the fact that his criteria for fitting the CFA model were considerably less restrictive than those considered by us. Specifically, Chen (2016) considered as appropriate his 5-factor model of the TEI by accepting as sufficient the following values: RMSEA = .062; χ2/ df = 6.15. This may imply some instability in the factor structure originally reported (Chen, 2016), which might be confirmed in other studies that replicate it. Thus, in light of the above we are unable to confirm our initial hypothesis, H1.

The internal consistency analysis demonstrated appropriate reliability indices for the four subscales of happiness, anger and fear, meeting the standards desired for this type of instrument (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). However, the subscale addressing a love produced only acceptable reliability (α = .68) relative to earlier results (Chen, 2016; 2018). As such, the second hypothesis (H2) was confirmed.

There was evidence of convergent validity of the TEI-BSV as significant correlations were evident with all the measures studied in the expected directions. In particular, this was reflected by the convergence with the subjective well-being scales, i.e. with the PA and NA scales used as indicators of hedonic/affective subjective well-being. Similarly, there was convergence with the life satisfaction scale as an indicator of the cognitive/evaluative component of subjective well-being. As a result, the third hypothesis (H3) is confirmed.

Both life satisfaction and the EI trait were positively correlated with the love and happiness subscales, and negatively with the anger and fear subscales. Significant negative associations were found between the love and happiness subscales and the burnout dimension. Conversely, significant positive associations were observed between the anger and fear subscales and the burnout dimension. Finally, significant positive associations were found between the love and happiness subscales and the engagement dimension. In addition, the anger and fear factor scores were negatively correlated with the vigour and dedication subscales. Likewise, and as hypothesized, evidence of concurrent criterion validity was also obtained. Thus, the TEI-BSV appears to have predictive power with respect to the three dimensions of burnout and of engagement, such that H4 is confirmed.

Multiple regression analyses revealed that the TEI-BSV subscales explained a significant proportion of the variance in burnout and self-fulfilment, and to a lesser extent depersonalization. The fear subscale explained the largest variance in the exhaustion subscale, while the happiness subscale explained the greatest variance in the self-fulfilment subscale. The results also revealed that the TEI-BSV subscales explained a significant proportion of vigour, dedication and, to a lesser extent, absorption. The fear subscale accounted for the largest variance in the exhaustion subscale, while the happiness subscale explained the largest variance in the engagement subscales.

In Model 2 of the hierarchical regression, EI was confirmed as a significant predictor of both burnout and engagement scales as expected (Barreiro & Treglown, 2020; Fiorilli et al., 2019). Subsequently, when adding the TEI-BSV scales as predictors, the variance explained by the model increased significantly in all six regressions, as witnessed by the incremental validity of the TEI-BSV with respect to the consolidated predictive power of the EI trait in predicting burnout and engagement. However, it should be noted that the fear subscale of the TEI-BSV was the only one that did not persist as a significant predictor in these hierarchical regressions. As a consequence of the above, H5 is confirmed.

A comparative examination of the results in Tables 5 and 6 shows that the TEI-BSV showed higher criterion validity than the TEIQue-SF in predicting burnout and engagement. For example, EI explained only 10% of the variance in exhaustion as a single predictor, while the set of four TEI-BSV scales explained 29% of the variance in that same criterion variable. This pattern is repeated for the rest of the elements associated with burnout and engagement, with the exception of the prediction of vigour where the EI trait explained 16% of the variance and the TEI-BSV explained only 14% of the variance. Without doubt, these results validate the potential of the TEI-BSV for its use in future research on teachers' emotions, and their relationship with processes that trigger or maintain burnout and engagement.

The present study has a series of limitations such as the use of convenience sampling. It would be convenient to carry out random sampling to favour the possibility of making generalizations from the results. The number of female teachers doubles that of males and as such, an effort to balance the gender composition should be made, although it is important to note that our population reflects the current gender distribution of the teaching population in Spain. Furthermore, the participation of the teaching staff in completing the questionnaires was completely voluntary and it is possible that the teachers who volunteered might be those who are more motivated when carrying out their work. From a psychometric point of view, it should be noted that the instruments used are self-report tests, which implies potential bias in the results, such as acquiescence, social desirability or common method variance between predictors and criteria. The addition of tests employing heterologous assessments could enrich our results.

In terms of future lines of research, it might be of interest to explore the possible variables that mediate and moderate these facets, such as gender. Moreover, the development of an emotional education program for teachers based on the diagnosis of emotional needs highlighted through studies with the TEI-BSV could be of particular value.

The psychological, theoretical and practical implications of the present study are worthy of note. Firstly, while certain emotional states like burnout and engagement are related to personality factors such as EI, they are more closely related to a teacher’s emotional states during the practice of teaching. Secondly, the TEI-BSV appears to be an interesting tool the sue of which could aid the understanding of the emotional state of teachers, which in turn could help improve teacher training programmes. Thirdly, understanding the affective-emotional state of teachers could prevent future difficulties in the performance of their professional tasks, as well as in their well-being and mental health. Fourthly, the TEI-BSV is an instrument that might drive the introduction of improvements into teaching-learning processes (Chen, 2021). Finally, the TEI-BSV represents a short, reliable, valid and free instrument to study emotional states in teachers.

Conclusions

The TEI-BSV has adequate psychometric properties with a view to evaluating the emotional dimension of a teachers' work within the educational system in a Spanish-speaking context, which offers some advantages both in terms of research and for application in educational centres. As indicated previously (Gosling et al., 2003), shorter instruments may favour the cooperation of certain populations, like teachers, who respond better to these than to more extended and tedious instruments. Indeed, given that the TEI-BSV evaluates emotions “strictly related” to the daily work context of teachers, it is well adapted to use in ecological studies of the emotional dynamics of teachers, for example following the Ecological Momentary Assessments approach (EMA) that has been very popular in recent years (Wrzus & Neubauer, 2022). Using such an EMA approach, frequent evaluations are sought on the variables of interest in diagnostic studies or when evaluating interventions, thereby better understanding subjective experiences and their possible dynamic variations over short periods of time. We believe that the TEI-BSV is not only compatible with but ideal for use in EMAs.

texto en

texto en