Introduction

The use of Social Networking Sites (SNS) such as, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram has become widespread over recent years (Koç & Akbıyık, 2020). Researchers argue that users' narcissism and the popularity of SNSs are related, and that social networking activities reflect narcissistic traits (Fishwick, 2016). People use social networking sites for a range of purposes, such as seeking friends, social support, entertainment, information sharing, and business (Kim et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2012). The extensive use of social networking sites has fascinated social, personality, and clinical psychologists who seek to determine the range of adaptive and maladaptive behaviors associated with social networking sites usage, as well as personality types (Fox & Rooney, 2015; Grieve et al., 2013; Tandoc Jr et al., 2015). A core feature of social networking sites is to provide an interactive and agentic environment where individuals can promote and enhance themselves (Twenge & Campbell, 2009). The focus of recent research has been the behaviors and personality associated with these features. For instance, regular use of Facebook is associated with large numbers of friends and strong social capital (Ellison et al., 2007; Valenzuela et al., 2009), self-promoting behavior (Abell & Brewer, 2014) and particularly, with narcissism (Brailovskaia & Bierhoff, 2016; Walters & Horton, 2015).

A grandiose feeling of self-importance, a lack of empathy for others, a need for excessive adulation, and the conviction that one is special and deserving of preference are all characteristics of narcissism. Narcissism is more correctly described as a hunger for admiration or praise, a desire to be the center of attention, and an expectation of special treatment reflecting a perceived elevated status. It does not necessarily signify an excess of self-esteem or a lack of insecurity. Narcissism is a tendency to perceive the self as superior and grandiose (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Narcissism has been categorized into two distinct subtypes: narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability. Narcissistic grandiosity refers to maladaptive self-enhancement tactics that function in self-promotion. It largely mirrors the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5 criteria for narcissistic personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Narcissistic vulnerability refers to self-dysregulation (an inability to maintain a consistent self-image), shame, and psychological distress in response to interpersonal rejection or competitive failure (Ronningstam, 2009). The former is widely conceptualized as narcissism in Social-Personality psychology and has been investigated in terms of the range of self-enhancement and self-promoting behavior that occurs on social networking sites. Narcissism has been found to be associated with the frequency of status posting (große Deters et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2015), picture posting, and selfie posting behavior (Sorokowski et al., 2015).

Additionally, a core factor underlying these behaviors, and particularly narcissism, is perfectionism (Casale et al., 2016). One of the most influential conceptualizations of perfectionism comes from a multi-dimensional model (Hewitt et al., 1991) that characterizes three forms of perfectionism: self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed. Self-oriented perfectionism is characterized by being critical of oneself, or the belief that being perfect is important. While other oriented perfectionists expect others to be perfect and are highly critical of others who fail to meet these expectations (Hewitt et al., 1991; Stoeber, 2014). Finally, socially prescribed perfectionism refers to externally shaped belief that striving for perfection and being perfect are important to others.

The relationship of narcissism with self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism has been investigated in a number of studies, and others-oriented perfectionism has merged as the only form to which it has positive unique relationships (Sherry et al., 2014; Stoeber et al., 2015). However, the association of narcissism with self-promoting behavior on social networking sites and the potential role for perfectionism in this context has not been studied extensively. Given this lack of research, further investigation is warranted. Additionally, recent researches have also established that spontaneous and recurrent effort for the attainment of a “flawless selfie” can exaggerate self-consciousness and subsequently leads to insecurities related to social approval, lack of adequate social admiration and response on the selfie can lead to a devastative influence on a person’s self-esteem and confidence level.

Social networking sites (SNS) like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter are another factor that is linked with narcissism and perfection and is becoming more and more popular, and this has led to speculations that an intense use of these platforms is indicative of narcissistic traits. Recent analysis of this matter, meanwhile, has been all but definitive. While some empirical studies (Fox & Rooney, 2015) found evidence supporting a positive link between narcissism and social networking behavior, other studies (Panek et al., 2013) reported mixed or even negative effects (Skues et al., 2012).

The current media culture, which is thought to reflect and affect people's narcissism, has been linked to variations in narcissism throughout time and places (Twenge, 2013). Mass media functions both unexpectedly and by intent in the socialization process of community and transmit the culture of the broader society in terms of beliefs, values, philosophy, formal and informal behavior, and habitual patterns. It is a basic perception that youngsters watch and appreciate models of television and they attempt to look like them (Nigar & Naqvi, 2019). In many cultures and world regions, the engagement in SNSs has become an immensely popular pastime activity (Gnambs & Appel, 2018). Therefore, potential factors associated with narcissism, perfectionism, and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites in a Pakistani context has been overlooked. Consequently, we sought to determine whether narcissism is associated with a range of socio-demographic factors and self-promoting behavior in Pakistan, and to ascertain whether distinct dimensions of perfectionism mediated any of the observed associations.

Closely related is the topic of problematic social networking sites usage defined by Ames et al. (2006) as being preoccupied and motivated with the strong usage of social networking sites, and leading to impairments in social, personal and/or professional life, as well as psychological health and wellbeing. Some research studies highlighted the impact of social networking sites such as Facebook on the psychological health of college students (Koc & Gulyagci, 2013). Others have talked about the impact of Facebook addiction on the narcissistic behavior and self-esteem (Malik & Khan, 2015). Prevalence rates of individuals suffering from problematic use with one study (Tang & Koh, 2017) reported that 29.5% of the sample experienced negative consequences due to problematic social networking sites usage. Bányai et al. (2017) showed in one nationally representative study that among nearly 6000 Hungarian teenagers, 4.5% reported to be at risk of developing a problematic social networking sites usage.

A study conducted in the Chinese sample indicated that young Chinese individuals are found to score more on instruments measuring narcissism (Cai et al., 2012). Cross temporal meta-analysis conducted by (Khazaie et al., 2021; Konrath et al., 2011) indicated that dispositional empathy has declined across the time. It is speculated by some of the researchers that the increase in the narcissism has accompanied the rise of media usage and media is the potential factor that may be contributing towards the increase of the narcissism level across the time (Gibson et al., 2016). The other factor of perfectionism which is characterized by a person's striving for flawlessness and setting excessively high performance standards, accompanied by overly critical self-evaluations and concerns regarding others' evaluations (Rahmat et al., 2022; Stoeber & Childs, 2010). Researcher anticipated that perfectionism will mediate the relationship between narcissism and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites.

Although social media use can have many benefits such as forming and creating online communities to help each other (Allen et al., 2014), improve cooperation and share information (Siddiqui & Singh, 2016), allow people to connect with friends and other people across the globe, allow convenient communication, information transfer (Ittefaq & Iqbal, 2018) and help break down social boundaries (Phua et al., 2017), it can also lead to problematic social media usage and can lead to problematic personality traits (Hussain et al., 2021; Shoib et al., 2021).

Since the launch of the first social media website, narcissism and social media use have been studied as a link. While many meta-analyses have been carried out to compile empirical evidence on the relationship between narcissism and typical online behaviors (such as uploading photos and usage frequency), there is still a lack of systematic evidence on the relationship between narcissism and Problematic Social Media Use (PSMU). Over the past few years, there has been a noticeable surge in social media usage. Around 2.46 billion people used online social networking services (SNSs) worldwide in 2017, and by the end of 2021, it is predicted that there would be 3.09 billion social media users worldwide. Facebook (FB) alone had 2.45 billion monthly active users as of October 2019. Recently, Instagram (IG) reached 1 billion monthly active users, the great majority of whom use it every day (Statista, 2020).

Since it appears that the social media setting provides the optimal communicative environment to satiate narcissistic desires, research on narcissism and social media use has become increasingly popular in recent years (Bergman et al., 2011). Theoretical claims that social media are the best places to pursue narcissistic objectives have received special attention. In fact, due to a number of characteristics, SNSs appear to be the perfect medium for expressing grandiosity and attracting desired attention (Barry & McDougall, 2018). First, compared to face-to-face contacts, SNSs provide users more control over how they show themselves, making them an ideal setting for the practice of savvy interpersonal behaviors, many of which narcissists use to create and maintain a well-constructed sense of self (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Second, using social media enables users to share their accomplishments with a wide audience and get visible incentives and recognition in the form of "likes" and complimentary remarks from other users (Andreassen et al., 2017). Additionally, SNSs are available anywhere and anytime due to the increase in SNS usage on mobile devices. This suggests that narcissists are able to constantly edit, control, and promote an online "self" while also getting regular feedback on how they're doing.

Earlier studies in Pakistan have focused on the mental health issues such as relationship between narcissism and self-esteem with aggression (Anwar, 2016) and the role of perfectionism in psychological health (Butt, 2010). Others have tried to establish the relationship between narcissism and selfie posting motivation among Pakistani youth (Saleem, 2016) and use of social media and political participation among university students and have found that majority of the students using social media use it as a tool to gain political information (Ahmad et al., 2019) and digitalizing the health sector (Ittefaq & Iqbal, 2018).

Few studies have also conducted a thorough analysis of the nature of sex differences in narcissism or examined the comparability of measurement across genders. Given that narcissism is a psychological characteristic linked to significant outcomes, gender variations in narcissism may contribute to the explanation of observed gender disparities in these significant outcomes. Despite the possibility that gender similarities outweigh gender differences by a large proportion, certain persistent individual differences have been noted. There hasn't been a systematic review to determine the size, variability across measures and circumstances, and stability over time of this gender difference, despite the widespread notion that males are more narcissistic than women (Grijalva et al., 2015).

Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore the relationship between narcissism and self-promoting behavior as well as to explore the mediating role of perfectionism in the relationship between self-promoting behavior and narcissism among Pakistani sample. It was hypothesized that narcissism is positively correlated with self-promoting behavior and perfectionism is positively correlated with Narcissism and self-promoting behavior. It was also hypothesized that Narcissism is positively correlated with self-promoting behavior and that the relationship between narcissism and self-promoting behavior is mediated by perfectionism. The study intends to establish a relationship between problematic social media usage and its relationship with psychological health.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This study using correlational study recruited 605 student participants from universities and colleges within Islamabad and Rawalpindi, Pakistan employing convenient sampling method. The sample comprised nearly identical proportions of males and females (males: n = 307, 5.70%; females: n = 298, 49.30%). Graduate students (n = 309; 51.10%) were the most dominant, followed by undergraduates (n = 251; 41.50%), and post-graduates (n = 45; 7.40%). A large proportion of the sample reported their marital status as single (n = 560, 92.60%) and only a small proportion of participants were married (n = 45, 7.40%). With this diverse sample, we also wished to see if the age and study level has any impact on study variables. The age range was 18-35 years. Informed consent was obtained from all participants along with a booklet containing their answers to the scales and demographic questionnaires. Participants filled in the booklets in the presence of the researcher. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee Department of Psychology. Permission for data collection was obtained from the relevant institutional authorities. Individuals were excluded if (1) did not use Social Networking Sites, (2) were more than 35 years of age, or (3) were unwilling or unable to give informed consent.

Measures

Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI-16). The 16-item version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory measures the degree of narcissism among individuals (Ames et al., 2006). Each item is comprised of two statements and respondents must choose one statement that suits them. The statement in each item representing narcissistic self-views is scored as “1”, while the other statement is considered neutral and is scored as “0”. Overall, individuals can score between 0 and 16, with higher scores indicating higher levels of narcissism. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for current study is .83.

Self-promoting Behavior on social networking sites. A self-developed six question questionnaire on Self-promoting behavior on social networking sites was used after it was tested in preliminary research. Three questions address image posting behavior on social networking sites and include items like, “I update/change my own photo on social networking sites”, “I regularly check any comments or likes on my photos on social networking sites” and “I update/change my own photo as a profile picture on social networking sites”. The other three questions encompass the image editing/selection behavior on social networking sites and include questions such as, “I search for good photos of myself to upload on social networking sites” and “I crop/cut my photos before uploading them on social networking sites” and “I use different filters to make my photo more appealing on social networking sites”. The items are scored on a Likert scale from 1 (rarely) to 5 (almost daily) for a minimum total score of 6-3. The Cronbach’s α coefficient shows good internal consistency (α = .86). The scale mean was 13.30 (SD = 3.88) (seeTable 1for descriptive statistics).

Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale. The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale measures the degree of perfectionism (Hewitt et al., 1991). This scale comprises three dimensions, including self-oriented perfectionism; others-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism. It consists of 45 items to which participants respond on a 7-point scale (1= “strongly agree” to 7 = “strongly disagree”). Higher scores reflect greater perfectionism. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for current study is .87.

All the questionnaires used were in English language, since the participants were all students and the medium of teaching in Pakistan is English.

Results

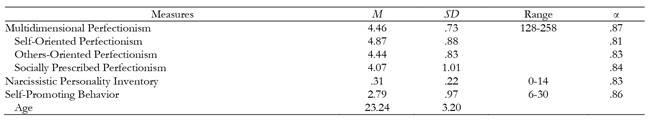

Table 1 shows the psychometric properties for the scales used in present study. The Cronbach’s α values for Multidimensional Perfectionism, Narcissistic Personality Inventory and Self-promoting behavior was .87, .83 and .86 respectively (> .80), which indicates high internal consistency.

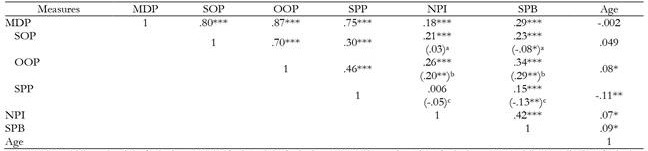

Table 2 shows the correlational analysis for the study variables. Strong positive correlations were observed between multidimensional perfectionism and its factors (r = .80, .87 and .75 respectively, p < .001). Narcissism demonstrated weak positive correlations with overall multidimensional perfectionism (r = .18, p < .001) and self-oriented perfectionism (r = .21, p < .001), and a stronger correlation with others-oriented perfectionism (r = .18, p < .001). Of note, no significant partial correlation of narcissism was observed for self-oriented perfectionism after statistically controlling for others-oriented and self-prescribed perfectionism. Similarly, narcissism did not significantly correlate with socially prescribed perfection with or without controlling for self-oriented and others-oriented perfectionism. Others-oriented perfectionism was the only facet of perfectionism that demonstrated a significant positive partial correlation with narcissism after statistically controlling for self-oriented and others-oriented perfectionism. Self-promoting behavior correlated positively with multidimensional perfectionism (r = .29, p < .001), self-oriented perfectionism (r = .23, p < .001), others-oriented perfectionism (r = .34, p < .001), socially prescribed perfectionism (r = .15, p < .001), and narcissism (r = .42, p < .001).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation for study variables.

Note.MDP, Multidimensional Perfectionism; SOP, Self-oriented Perfectionism; OOP, Others-oriented Perfectionism; SPP, Socially Prescribed Perfectionism NPI, Narcissistic Personality Inventory; SPB, Self-promoting Behavior.

aPartial correlation controlling for OOP and SPP;

bPartial correlation controlling for SOP and SPP;

cPartial correlation controlling for OOP and SPP;

*p < .05, two tailed;

**p < .01, two tailed

***p < .001, two tailed

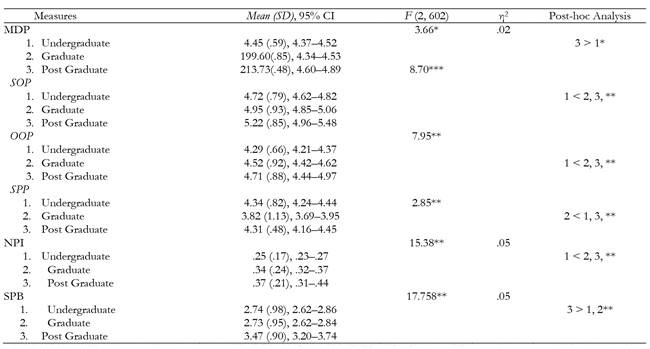

Table 3 shows mean, standard deviation and F-values for Perfectionism, Narcissism, and Self-Promoting Behavior across Educational Levels. Results indicated significant mean differences across educational levels on multidimensional perfectionism with F (2, 602) ** 3.66, p < .05. Findings revealed that Post Graduate students showed higher levels of perfectionism as compared to graduates and undergraduates. The value of .02 (<.50) which indicates small effect size. Post-Hoc comparisons (Tukey) indicated significant between group mean differences of each group with other two groups. The results indicated significant mean differences across educational levels on narcissism with F (2,602) ** 15.38, p <.01. Findings revealed that post graduates exhibited higher levels of narcissism as compared to graduates and undergraduates. The value of .05 (<.50) indicates small effect size. The Post-hoc Comparisons indicated significant between group mean differences of each group with other two groups. Furthermore, undergraduates exhibited higher levels of self-promoting behavior as compared to graduates and postgraduates. The value of .05 (<.50) indicates small effect size. The Post-hoc Comparisons indicated significant between group mean differences of each group with other two groups.

Table 3. Mean, Standard Deviation and One-Way Analysis of Variance in Perfectionism, Narcissism, and Self-Promoting Behavior across Educational Levels.

Note.MDP, Multidimensional Perfectionism; SOP, Self-oriented Perfectionism; OOP, Others-oriented Perfectionism; SPP, Socially Prescribed Perfectionism; NPI, Narcissistic Personality Inventory; SPB, Self-promoting Behavior;

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001

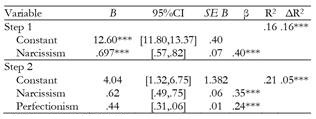

Table 4 shows the impact of narcissism and perfectionism on self-promoting behavior among study participants. In Step 1, the R2 value of .16 revealed that the narcissism explained 16% variance in participants with F (1, 603) = 112.80, p < .001. The findings revealed that narcissism positively predicts self-promoting behavior (β = .40, p < .001). In step 2, the R2 value of .21 reveals that the narcissism and perfectionism explained 21% variance in the participants with F (2, 602) = 8.98, p <.001. The findings revealed that narcissism (β = .35, p < .001) and perfectionism positively predicted self-promoting behavior (β = .24, p < .001). The ΔR2 value of .05 revealed 5% change in the variance of model 1 and model 2 with ΔF (1, 602) = p < .001. The regression weights for the narcissism subsequently reduced from Model 1 to Model 2 (.40 to .35) but remained significant which confirmed the partial mediation. More specifically, narcissism has direct as well as indirect effect on self-promoting behavior.

Table 4. Regression Analysis for Mediation of Perfectionism between Narcissism and Self-promoting behavior.

Note. CI = Confidence interval.

***p < .001

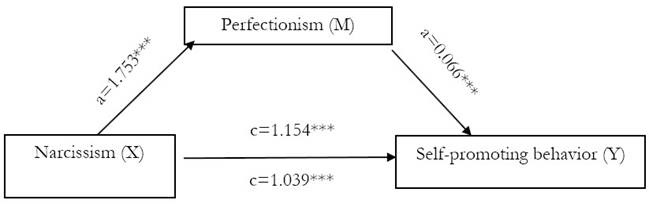

Further mediation analysis using PROCESS Macro 4.1 in SPSS shows that overall narcissism significantly influences perfectionism and self-promoting behavior as well as perfectionism has a mediating effect in the relationship between narcissism and self-promoting behavior.

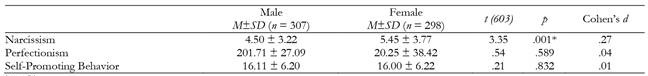

Further analysis in table 5 show significant mean differences on narcissism with t (603) = 3.35, p < .01. Findings reveal that females scored higher on narcissism (M= 5.45, SD = 3.77) compared to males (M= 4.50, SD = 3.22). The value of Cohen’s d was .27 (< .50) which indicated small effect size. Findings revealed non-significant mean differences on perfectionism t (603) = .54, p > .01, with the value of Cohen’s d of .04 (< .50) indicating small effect size. As well as non-significant mean differences were found on self-promoting behavior t (603) = .21, p > .01, with the value of Cohen’s d of .01 (< .50) indicating small effect size.

Table 5. Mean Comparisons of Gender Differences on Narcissism, Perfectionism and Self-promoting Behavior.

*p < .01

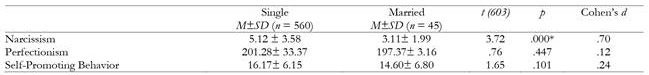

Table 6 below shows significant mean differences on narcissism with t (603) = 3.72, p < .01. Single participants scored higher on narcissism (M= 5.12, SD = 3.58) as compared to married participants (M= 3.11, SD = 1.99). The value of Cohen’s d was .70 (> .50) which indicated medium effect size. Findings revealed non-significant mean differences on perfectionism t (603) = .54, p > .01, with the value of Cohen’s d of .04 (< .50) indicating small effect size. As well as non-significant mean differences were found on self-promoting behavior t (603) = 1.65, p > .01, with the value of Cohen’s d of .24 (< .50) indicating small effect size.

Discussion

In this study we examined the association between narcissism and (1) self-promoting behavior on social networking sites, (2) perfectionism, and (3) a range of demographics in a large sample of university students in Pakistan. The mediating role of distinct components of perfectionism (self-oriented, others oriented and socially prescribed) have been examined in relation to narcissism and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites. The findings of the current study suggest that there is a significant relationship among study variables. Furthermore, perfectionism has a mediating effect between narcissism and self-promoting behavior, as well as significant differences were found on gender and educational level among study participants.

Three dimensions of perfectionism showed meaningful and distinct patterns of correlations with narcissism and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites. Others-oriented perfectionism emerged as the only dimension that showed a positive relationship with narcissism after statistically controlling for the variance of the rest of the components of multidimensional perfectionism. This finding is consistent with past findings in which others-oriented perfectionism was the only form showing significant positive association with grandiose narcissism, as assessed by the NPI (Stoeber, 2014; Stoeber et al., 2015). Further, others-oriented perfectionism exhibited a significant positive relationship with self-promoting behavior on social networking sites. The relationship of others-oriented perfectionism with narcissism and self-promoting behavior supports the view that narcissists and others-oriented perfectionists predominantly externalize their behavior. Indeed, others-oriented perfectionists tend to be authoritarian, egotistical, mistrustful, and cold in social relationships, while remaining unaware of the emotional turmoil they create for others (Yaghoubi, 2014). This combination makes others-oriented perfectionism important for interpersonal functioning, particularly in a Pakistani interdependent cultural context. In contrast, after statistically controlling other components of perfectionism, self-promoting behavior on social networking sites showed a significant negative relationship with self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism. This finding agree with the wider literature suggesting that self-oriented perfectionism may be associated with silencing and concealing behavior (Flett et al., 2007).

Further, by using a parallel mediation model analysis (Hayes, 2013), we determined that narcissism indirectly influenced self-promoting behavior on social networking sites through self-oriented and others-oriented perfectionism, but not through socially prescribed perfectionism. From the current findings, idealistic and perfectionist attitudes directed towards others and oneself clearly explain the relationship between narcissism and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites. First, narcissism positively predicts others-oriented perfectionism, which in turn positively predicts self-promoting behavior on social networking sites. Indeed, narcissists tend to make an example of their perfectionist attitudes and behaviors by highlighting and externalizing their positive aspects for others. In contrast, narcissism positively predicts self-oriented perfectionism and self-oriented perfectionism negatively predicts self-promoting behavior on social networking sites. This shows that to some extent, some narcissists also have high standards for themselves as well, which in turn leads them to inhibit themselves from using social networking sites for self-promotion.

The findings indicated that female participants scored higher than males on narcissism. Contrary to our findings, past studies have reported that males score higher on narcissism; particularly on narcissistic grandiosity (Twenge & Campbell, 2003). Nevertheless, these data were collected from the university students, and recent evidence has indicated increased use of technology (exposure to TV or use of social networking sites) among university students in general (Twenge et al., 2008). In a Pakistani cultural context, women have fewer opportunities for real-life interactions than men thus, females might be more prone to use of technology for social interactions and entertainment. At the same time, a strong relationship exists between use of media and narcissism (Casale & Banchi, 2020; Twenge & Campbell, 2009). Collectively, the vulnerability to excessive media usage among females in universities due to cultural values and the relationship of narcissism with media use might explain our findings and warrant further investigation.

Furthermore, scores on narcissism were associated with higher levels of educational achievement. Previous studies (Onley et al., 2013; Papageorgiou et al., 2017) found relationship between narcissism and mental toughness and suggested that it can lead to educational achievement. Papageorgiou et al. (2018) found that subclinical narcissism was positively associated with mental toughness which in turn was associated with higher school achievement. Individuals who score high on narcissism often have difficulties in maintaining long-term relationships and having good marital relationships (Campbell & Foster, 2002; Miller & Campbell, 2008), and narcissists tended to be less committed than non-narcissists at low levels of communal activation (Finkel et al., 2009) because of their domineering and controlling approaches to others (Ogrodniczuk et al., 2009). Our findings indicated that single participants scored higher on narcissism than those who were married, and further investigation is required to determine whether individuals with narcissistic traits have difficulty searching for a spouse (due to their selective nature or some other possible reason) or difficulty keeping relationships.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, data were collected using a cross-sectional design, thus, although associations were demonstrated between narcissism, perfectionism, and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites, caution is required in the interpretation of these findings (as causal interpretations are not applicable). Second, due to small sample size the generalizability of the findings on the larger population is not possible, future researchers should be done on a larger sample size.

Implications and recommendations

The results of this study have some implications on the growing field of Internet and social media research, the valuable evidence of various social networking processes, the most common and striking area of influence is the information of how the behavior, underlying human attitudes are influencing other people through networking and interpersonal ways.

Social media use continues to grow especially among adolescents. Because many of today’s adolescents are spending most of their lives connected to social media, it is very important for researchers to discover how narcissism predicts various underlying behaviors associated with social media the use.

Future researches should be done to elaborate the findings on the basis of gender, such as investigating narcissistic traits and the underlying behavioral components that influence SNS utility among males and females. Future research should be done on how interplay of perfectionism and self -promoting behavior can be related to the narcissism, like manipulation of one’s appearance on the utility of SNS done by individuals because narcissists are more vulnerable of social comparability. In future researches should be done to show how underlying insecurities among narcissists compel them to get involved in photo modification and frequent selfie posting behaviors.