Introduction

Although one of the greatest desires in human life is to be happy, the scientific study of happiness and the factors that influence people's well-being only began in the last decade of the 20th century (Rojas, 2021). Lyubomirsky (2008) refers to happiness as a feeling of joy, satisfaction, and living in a state of well-being, which at the same time leads people to feel that they have a good life, with meaning, and therefore worth living. At the same time, happiness has been identified as one of the five pillars of positive psychology (whose central mission, according to Wood and Johnson (2016), is to identify, develop and evaluate interventions to improve well-being), along with engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement, as the enduring building blocks of a life of deep fulfilment (Seligman, 2011). Despite the theoretical or operational differences when defining well-being or happiness concepts, there is an agreement on what the cognitive, affective, and social elements are related to them (Verdugo-Lucero et al., 2013; Gómez et al., 2007).

Traditionally, theories of well-being have considered two essential dimensions: cognitive, which corresponds to satisfaction with life, understood as a global assessment that an individual makes about his life (Pavot et al., 1991), while affective refers to the presence of positive feelings and corresponds to the concept of happiness (Arita, 2014). Later, Diener et al. (2017) argued that subjective well-being “is a broad umbrella term that refers to all different forms of evaluating one’s life or emotional experience, such as satisfaction, positive affect, and low negative affect” (Diener et al., 2017, p. 87). Moreover, happy people have better cardiovascular health and are engaged in healthier behaviours (Boehm et al., 2012), have better immune functioning (Marsland et al., 2006), and are longer-lived (Diener & Chan, 2011).

Diener et al. (2013) saw satisfaction with life as a global assessment of feelings and attitudes about one's life at a given moment, ranging from negative to positive, and Veenhoven (1996) refers to the degree to which a person assesses the overall quality of their life, i.e. how satisfied they are with the life they lead. In the words of Ellison et al. (1989), satisfaction with life is a cognitive assessment of an underlying state that appears to be relatively consistent and influenced by social factors. It could be said that it is a purely subjective state based on variables that an individual finds personally important in his or her life.

In general, there are two main types of theories about satisfaction with life: ascendants, considering the satisfaction of multiple areas of life (work, relationships, family and friends, personal development, health, and fitness), and descendants referring to the satisfaction in specific domains (Headey et al., 1991). However, descendants claimed that our overall satisfaction with life influences (or even determines) our satisfaction with life in different areas.

The level of satisfaction with life also varies by education and countries with higher levels of education generally experience higher levels of satisfaction (Ruggeri et. al., 2020). It is interesting to note, however, that at the individual level, the effect of education on satisfaction with life is stronger when few people in the country have achieved the same level of education. For example, a person with a bachelor's degree in a country with a lower-middle education is likely to experience a greater boost in satisfaction with life than a person with a bachelor's degree in a higher-educated country (Salinas-Jiménez et al., 2011).

Satisfaction with life is closely related to positive affect, and both are predictors of health behaviour (Kushlev et al., 2020). Maintaining a high positive affect implies multiple health benefits: it favours the ability to cope with adversity, protects against depression, allows better tolerance of physical pain, improves the immune system, and favours a more open, creative, and flexible cognitive organization (Vázquez & Hervás, 2009). Likewise, positive affect has been linked to reducing inflammatory markers and cardiovascular stress (Steptoe et al., 2012), decreasing depression (Xu et al., 2015), reducing the risk of mortality, the onset of the disability and coronary heart disease, regardless of risk factors and negative affect (Blazer & Hybels, 2004; Kubzansky & Thurston, 2007).

Gratitude and its influence on amplifying satisfaction with life is also a topic widely studied in positive psychology. For example, Watkins et al. (2015) postulated that when a positive event is remembered with gratitude, it will positively impact people's subjective well-being. Feeling gratitude influences people's affect and, implicitly, their happiness and satisfaction with life, and showing gratitude contributes to making and maintaining longer-term social relationships, having positive expectations, and giving social meaning to life, although the decision to show gratitude is independent of maintaining an overall positive affective state (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006).

In view of the relationships described between satisfaction with life, happiness, affect and the emotion of gratitude, the aim of this study was to assess whether gratitude emotions are a mediator variable to subjective happiness, affect, and satisfaction with life. The following specific objectives were formulated: 1. Analyze whether satisfaction with life is related to subjective happiness, positive and negative affect, psychological disturbance, and the emotion of gratitude; 2. Determine whether satisfaction with life is predicted by subjective happiness, positive and negative affect, psychological disturbance, and the emotion of gratitude, and 3. Analyze whether the feelings of gratitude mediate the relationship between satisfaction with life and the rest of the variables mentioned.

Method

Participants

Using an incidental non-probabilistic sampling, 1537 participants from across Spain took part in this study; 50% lived in the community of Madrid, 28.40% in Andalusia, and 21.6% in the rest of the autonomous communities. Of the total number of participants, 73.6% were females (1,131), and 26.4% were males (406). In terms of age, 50% were under 46 years old (M = 42.56; SD = 16.29).

The inclusion criteria were being of legal age, currently living in Spain, not suffering psychological disturbance, and giving informed consent to participate in a study on subjective happiness, positive and negative affect, emotions of gratitude, and satisfaction with life.

Instruments and Variables

The sociodemographic variables considered were gender (females and males), age, and current place of residence (Madrid, Andalusia, and other autonomous communities of Spain). To evaluate the overall judgment that a person makes about satisfaction with his or her life, the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) by Diner et al. (1985) was used (α = 0.87). It is composed of five statements, such as "Most aspects of my life are as I want them to be." The statements were answered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 - strongly disagree, up to 7 - strongly agree). In the current study, the Spanish version proposed by Atienza et al. (2000) was used. Its internal consistency is α = .84 and higher values were obtained with the sample of our study (α = .93 and ω = .93).

The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) by Lyubomirsky and Lepper (1999) shows the concept of subjective global happiness across four items, and its internal consistency ranges from good to excellent (α = .79 - .94). Two of the items require people to describe themselves using absolute life assessment criteria or endpoints to others, and the other two presents brief descriptions of happiness. Participants are asked to indicate to what extent these descriptions fit on a 7-point Likert scale. The SHS validation in Spanish proposed by Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal (2014) was used, which has very good internal consistency (α = 0.81). In the sample of our study, similar values were obtained (α = .80; ω = .83).

To assess the affect, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) by Watson et al. (1988) was used. It is made up of twenty items to which participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale on how they generally feel (from 1 - nothing to 5 - a lot). On the original scale, high Cronbach's Alpha reliability indices were obtained, ranging from .86 to .90 for positive affect and from .84 to .87 for negative affect. In the current study, the Spanish validation proposed by López-Gómez et al. (2015) was used, with a Cronbach's alpha of .92 for the positive affect scale and .88 for the negative one. With the sample of this study, α = .95 and ω = .95 were obtained for the positive affect, and α = .90 and ω = .90 for the negative one.

In measuring psychological disturbances, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) by Goldberg and Williams (1988) was used. It is a one-dimensional general health screening instrument designed to detect possible psychological morbidity in the general population and consists of twelve items (six positive and six negative phrases) that are answered on a 4-point Likert scale. In the case of positive items, the correction goes from 0 (always) to 3 (never), and in the negative ones, from 3 (always) to 0 (never). A higher score equals worse overall health. We used the GHQ-12 validation in general Spanish population carried out by Rocha et al. (2011) was used. The instrument had an adequate internal consistency (α = .86), and with the sample of our study, a similar value was obtained (α = .87; ω = .88).

Gratitude emotion has been assessed using the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) by McCullough et al. (2002). It is made up of six items that are answered using a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 - strongly disagree, to 7 - totally agree). The internal consistency quotient of the original test is α = .82, and the Spanish version validated by Martínez-Martí et al. (2010) has an internal consistency of α = .95. With the sample of this study α = .80 and ω = .85 were obtained.

Procedure

Data collection was carried out during January and May of 2022. The online survey took an average of 18 min to complete and was created in Google Forms. The link and QR code to access it was distributed through email, smartphone applications, posters, etc. All participants gave their consent to be part of the study.

Data Analysis

The Cronbach's Alpha (α) and Omega (ω) statistics were used to estimate the internal consistency of the scales. The normality of the variables was first estimated. Significant values were confirmed in the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilks tests. However, given the large sample size, the use of parametric tests was considered appropriate. In addition, the Pearson correlation and multiple linear regression tests were used. The assumptions of independence and collinearity were tested through the Durbi-Watson, IVF, and tolerance tests. Mediation models were carried out, and the definition of these was made based on the structure of Model 4, with 10,000 bootstrap samples and a confidence level of 95%. All analyzes were replicated considering the gender (male or female) and using the student t test for independent samples and the effect size from Cohen's D.

The interpretation of the results was based on the indications given by Pardo and San Martín (2015). Analyzes were performed with the SPSS IMB Statistics v.21, and the PROCESS macro for SPSS.

Results

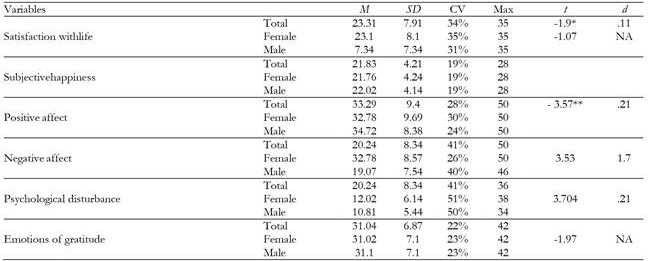

The descriptive analysis of the sample and the contrast tests between females and males are shown in Table 1: mean (M), standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), maximum (Max), statistic t (t), and effect size (d). The latter was not estimated when there were no significant differences (NA - not applicable).

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of study variables and inference according to gender.

Note. *p < .05;

**p < .01.

In general, the scores were homogeneous (CV less than 30%). There were significant differences, with weak and medium effect sizes, in satisfaction with life and positive affect in favour of males.

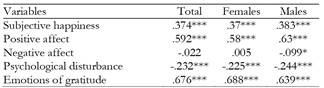

Table 2 shows the correlation values between life satisfaction and the other measured variables, both for the total sample and for females and males.

Table 2. Correlation analysis between satisfaction with life and the rest of the variables.

Note. *p < .05;

**p < .001.

Subjective happiness, positive affect, and gratitude emotions were found to have a significant and positive relationship with satisfaction with life. Psychological impairment was significantly and negatively correlated with it. These results were given for both males and females. The negative affect was only negatively and significantly related in the male sample.

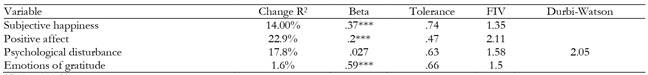

Regarding the general results of the regression, happiness, positive affect, and gratitude emotions were found to explain 56.10% of satisfaction with life (F(3, 1536) = 492.539; p < .001). The individual contribution of each variable is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. The individual contribution of variables to the model and values of the assumptions.

Note. ***p < .001.

The individual contribution of each variable to the model was significant, and positive affect explained the highest percentage of the variance of satisfaction with life. The psychological disturbance did not have a significant individual contribution. Therefore, it can be excluded from the equation without loss of adjustment (Pardo & San Martín, 2015).

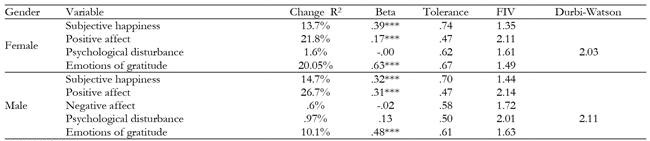

Depending on gender, different models were analyzed according to the results previously confirmed in the correlation. In females, four predictor variables were included: subjective happiness, positive affect, psychological disturbance, and emotions of gratitude. The model represented 57.4% of satisfaction with life (F(3, 1130) = 382.33; p < .001). In males, the variable negative affect was also introduced, as it presented a significant correlation with satisfaction with life. The model explained 52.2% (F(3, 405) = 89.423; p < .001) of satisfaction with life.

Table 4. The individual contribution of variables to the model and values of assumptions according to gender.

Note. ***p < .001.

In both females and males, subjective happiness, positive affect, and gratitude emotions were predictors of satisfaction with life. Psychological disturbance and negative affect in males were not variables that contributed significantly to the prediction models. Therefore, these variables can be excluded.

In females, the variable that most predicted their satisfaction with life was positive affect, followed by feelings of gratitude, subjective happiness, and psychological disturbance. In males, it was positive affect (as in females), followed by subjective happiness and emotions of gratitude.

Finally, the mediation models performed are presented. The dependent variable was satisfaction with life, the independent variable was subjective happiness, and positive affect and emotions of gratitude remained as mediating variables. These models were only performed when the variables presented significant individual forecasts.

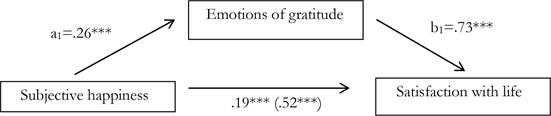

Figure 1. Model of gratitude emotions as mediators of subjective happiness and satisfaction with life.

A direct and significant effect of subjective happiness on the feelings of gratitude (β = .26; p < .001), of the latter on satisfaction with life (β = .73; p < .001), and subjective happiness on satisfaction with life (β = .52; p < .001) could be appreciated. Furthermore, an indirect and significant effect of subjective happiness on satisfaction with life mediated by gratitude emotions was observed (β = .19; p < .001). The moderation obtained was partial.

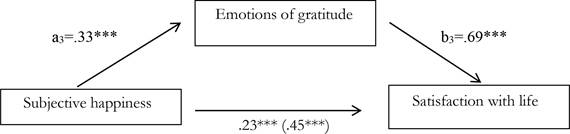

Figures 2 and 3 show that the mediation model is similar to the whole sample. However, in the model corresponding to females, the values obtained are slightly higher than those of males.

Figure 2. Model of gratitude emotions as a mediator between subjective happiness and satisfaction with life in females.

Figure 3. Model of gratitude emotions as a mediator between subjective happiness and satisfaction with life in males.

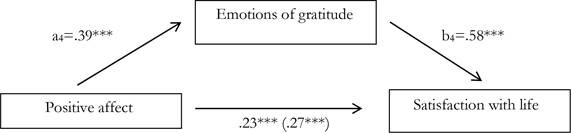

Figure 4 shows the results of the following mediation model: the independent variable is positive affect, and, again, the mediator is emotions of gratitude.

Figure 4. Model of gratitude emotions as mediators between Positive affect and Satisfaction with life.

There was a direct effect of positive affect on emotions of gratitude (β = .39; p < .001), of the latter on satisfaction with life (β = .58; p < .001), and of positive affect on satisfaction with life (β = .27; p < .001). Furthermore, an indirect and significant effect of positive affect on satisfaction with life mediated by gratitude emotions was observed (β = .23; p < .001).

Therefore, partial mediation was also proved.

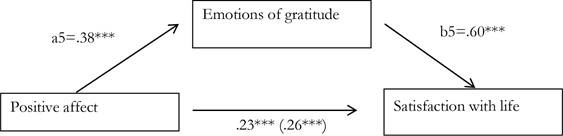

Finally, the figures below show the results of the model when the sample is differentiated according to being female (Figure 5) or male (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Model of gratitude emotions as a mediator between positive affect and satisfaction with life in females.

Figure 6. Model of gratitude emotions as a mediator between positive affect and satisfaction with life in males.

It was observed that the mediation model is similar to the complete sample. However, in the model corresponding to females, the values obtained are slightly higher than those obtained in males.

Discussion

Regarding the first specific objective raised in this work, it was observed that the greater subjective happiness, positive affect, and emotions of gratitude, the greater satisfaction with life is. In addition, low levels of psychological disturbance revealed high levels of satisfaction with life. These results were found in both male and female samples. To be highlighted was a negative relationship between negative affect and satisfaction with life that occurred only in males. Previous studies on affects in females and males have shown different results: females have more negative affect than males (Cazalla-Luna & Molero, 2018), or more positive affect than males (Alcalá et al., 2006), and even females and males do not differ in positive and negative affect (Cazalla-Luna & Molero, 2014). Regarding satisfaction with life, some studies have indicated higher satisfaction with life in females (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2004; Cazalla-Luna & Molero, 2018; Ortega-Álvarez et al., 2015; Tay et al., 2014), while others have shown that males have greater satisfaction with life (Haring et al., 1984; Stevenson & Wolfers, 2009) or that these differences do not exist according to gender (Okun & George, 1984). However, it is important to recognize that predominant emotions (positive or negative) affect the satisfaction with life of people (Chan, 2013; Ramzan & Rana, 2014; Watkins et al., 2015). If we look at the hedonic component of satisfaction with life, which depends on the constant appearance of positive affect and the scarcity of negative (Rodríguez-Fernández & Goñi-Grandmontagne, 2011), the less negative affect the men in this study felt, the more satisfied they were with their lives. Although satisfaction with life is conceptualized as a positive assessment that people make of their lives in general or concerning specific aspects of life, it is intimately linked to the interaction between the individual and his social environment. In this regard, Denegri et al. (2015) showed that the level of satisfaction with life is represented by a difference between aspirations and achievements that can range from personal fulfilment to experiencing failure or frustration.

About the second specific objective, it was seen that, at a general level, satisfaction with life was explained by positive affect, subjective happiness, and emotions of gratitude. Although psychological disturbance was a variable that correlated significantly to satisfaction with life, it cannot be considered a predictor, since its contribution to the model was not significant. In females, emotions of gratitude were the most predictive of satisfaction with life, followed by positive affect and subjective happiness. In males, it was a positive affect followed by subjective happiness and emotions of gratitude.

To date, there are no studies with large samples of adult participants on the four variables considered. Kausar (2018) identified that gratitude predicts happiness, Kerr et al. (2014) showed that gratitude can be developed and increases satisfaction with life, and positive affect plays a key role in feeling satisfied with life (Friedlander et al., 2018; Martínez-Pampliega et al., 2016; Sullivan & Lawrence, 2016). Diener (1984) mentioned that positive and negative affect is one of the two components that form subjective well-being along with satisfaction with life which constitutes the cognitive component. It is interesting to note that for women, gratitude is the second most predictive of satisfaction with life, while for men it is third. Beyond the emotional, Emmons (2008) considered three implicit elements, without which one cannot speak of gratitude: recognizing, appreciating and thanking. It would be interesting if future studies could provide data to support why emotions of gratitude and then subjective happiness are variables that produce greater satisfaction with life in women, and in men it is the other way around. At best, considering the other dimensions of gratitude, attitudinal, and behavioural, proposed by Morgan et al. (2017) could clarify these differences.

The psychological disturbance was a variable that did not predict satisfaction with life in either males or females. Neither were negative affect in males. By analyzing the descriptive sample of this study, it can be observed that, in a homogeneous and general way, the participants had low scores on both variables. Participants with very high scores can be considered outliers and cannot be eliminated since they meet the inclusion criteria.

Regarding the third and last specific objective, it was possible to verify that emotions of gratitude mediate the relationship between subjective happiness and satisfaction with life and between positive affect and satisfaction with life. In both cases, the higher people's subjective happiness or positive affect, the greater their satisfaction with life. In addition, the higher the level of feelings of gratitude a person has, the greater his or her satisfaction with life is. The results according to gender are very similar. The main difference lies in the values confirmed in the mediation models, where females were stronger than males. Previous research has shown that the systematic practice of gratitude carries multiple benefits: it lowers blood pressure, increases positive affect, and decreases negative one (Emmons, 2017), and increases subjective well-being and happiness with persistent results over time (Liao & Weng, 2018; Lyubomirsky et al., 2011; Manthey et al., 2016; O'Connell et al., 2018).

Although the results are a step forward for the scientific community, the study has some limitations and the sample was a decisive aspect, being made up of more females than males. For future research, it is appropriate to expand the number of male participants and to include people with different gender identities and expressions for a complete assessment of the indicators presented. Maybe a study focused on gender could clarify why females participate more than males in psychology research.

It would be appropriate to explore these models using other measurement instruments, mainly for subjective happiness and its cognitive components, and thus complete the information achieved in our study.

The mediation analyses carried out reflect partial mediation. It would be appropriate to deepen the relationship between emotions of gratitude and gender in addition to considering other components of it (behaviours or attitudes of gratitude), which also influence satisfaction with life.

Qualitative, intergenerational, and intercultural studies are recommended to contribute to deepening the findings on satisfaction with life, happiness, affect, and gratitude.

Conclusions

The positive psychology movement has devoted its efforts to the study of human strengths and virtues, consolidating the "science of positive subjective experience, positive individual traits, and positive institutions" (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p.5), and has been highly influential in a variety of fields including education (Seligman, 2019), healthcare (Waters et al., 2022), and business (Choi, 2020), to name a few. From the positive psychology perspective, it is understandable that human beings want to lead a meaningful and happy life, although the assessment criteria at the individual level differ and multiple factors are involved. The results of our study showed once again the gender differences, especially concerning satisfaction with life. Although gender is recognized as an important social determinant of health and well-being, gender differences related to well-being over time have been written about and will continue to be written about. When we talk about satisfaction with life, affect, subjective happiness, and gratitude, in short, we talk about well- being. Understanding them and taking them into account will help us to design programs and policies aimed to promote greater well-being in people that, ultimately, are about health preservation.