Introduction

Parental behavior represents a complex set of parental practices by which an individual tries to fulfill his/her parental role and achieve intended parenting goals (Newland, 2015; Obradović & Čudina-Obradović, 2003). Widely accepted classification of such behaviors refers to warmth and control (Baumrind, 1966). Parental warmth dimension has two poles; acceptance and rejection (Rohner, 2016), and is also often referred to as parental emotionality, i.e., the emotions that the parent shows in the relationship with the child (Džida et.al, 2020; Macuka, 2010). Part of this dimension is parental support by which parents make the child feel loved and accepted (Klarin & Đerđa, 2014). Control dimension refers to the establishment of a certain level of supervision and rules to limit the child's behavior and experiences (Macuka, 2007). There are two types of parental control, behavioral and psychological. The goal of behavioral control is the child's acceptance of the rules and standards of behavior that are in accordance with his/her environment. On the contrary, parents use psychological control to monitor children's emotions and thoughts, which negatively affects the child's psychological independence (Macuka, 2008).

In the past, parenthood was almost equaled with motherhood. Today, more attention is focused on the father's parenting. The reason for this is the change of social attitudes about the father's role in the family. Namely, in the past the role of a man as a family breadwinner was emphasized, while today a man is also expected to take over certain household chores and be more intensively involved in the child's development (Cvrtnjak & Miljević-Riđički, 2015; Pernar, 2010). Therefore, it is important to examine paternal behavior and its unique contribution to the child's development.

There are numerous factors influencing parental behavior. According to Belsky's (1984) process model of parenting, there are three groups of parenting determinants: characteristics of parents (e.g., gender, personality traits, developmental history, knowledge and beliefs about child development and parental behavior), characteristics of the child (e.g., gender, age, temperament, ability), and contextual sources of stress and support (e.g., marital status, work, social network).

Regarding parent gender, research results indicate that differences between maternal and paternal practices depend on the observed aspect of parenting. For example, differences were obtained in positive parenting, where mothers tend to be more acceptive and provide children with more autonomy and positive discipline (Sočo & Keresteš, 2011). In contrast, the same research found no gender differences in negative parenting practices, such as psychological control and negative discipline.

Researchers paid a lot of attention to the relationship between parent's personality traits and his/her parental practices. There are several personality models that researchers were guided by when studying the mentioned relationship, but the most used are the five-factor and the Big Five model, which include the traits of extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience (Costa & McCrae, 1988) or intellect (Goldberg, 1992).

Extraverted individuals show a tendency to establish frequent and high-quality relationships with other people, a need for continuous stimulation, and a tendency for positive affect (Huver et al., 2010). Therefore, it is expected that extraverts will achieve more positive interactions and quality communication with their child (Reić Ercegovac, 2011). According to research findings, more extraverted parents show more support, love and attention to their child, compared to less extraverted parents (Losoya et al., 1997). Belsky et al. (1995) associate the mentioned characteristics of extroverts with the father's "playfulness" and his positive parental involvement. Conversely, Huver et al. (2010) indicate that there is no evidence that extraversion predicts father's parental control, claiming that extraversion is associated with affective aspects of parental behavior, while the same isn't true for aspects of parental control.

Tension, agitation, and negative affect, which characterize individuals high on neuroticism, can be reflected in parental practices in two ways. On one hand, fathers with high neuroticism scores provide their children with less cognitive stimulation and are less emotional in their relationship with children (Belsky et al., 1995). Prinzie et al. (2009) suggest that parents high on neuroticism may be less supportive and less sensitive to their child's needs because of their preoccupation with their own emotions. On the other hand, parents' emotional stability negatively predicts their strict control, i.e., parents low on emotional stability dimension tend to have high expectations from their children and are impatient to know where their child is. That's why they often resort to exaggerated reactions with which they try to strictly control the child (Huver et al., 2010).

Conscientious fathers are expected to support their child's development in a structured environment with their responsibility and organization (Prinzie et al., 2009). Accordingly, Denissen et al. (2009) found conscientiousness to be a positive predictor of paternal emotional warmth. Regarding restrictive control, research indicate a negative connection between conscientiousness and negative control (Losoya et al., 1997). However, Denissen et al. (2009) state that it is not entirely clear why conscientiousness would be associated with restrictive control, since conscientious people already have a high level of control over various aspects of their lives, therefore they do not show the need to control other people.

Characteristics such as good character, willingness to help, trust, honesty enable agreeable parents to establish cooperation and trust in their relationship with their child (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006; Denissen et al., 2009; Huver et al., 2010; Reić Ercegovac, 2011). Research shows a negative correlation between agreeableness and negative affect traits such as anger and hostility. Therefore, it can be assumed that less agreeable parents tend to communicate more negatively with their child (Reić Ercegovac, 2011) and use other forms of negative parental behavior (Losoya et al., 1997). On the other hand, Prinzie et al. (2004) showed different results, according to which agreeable parents tend to be coercive, while Huver et al. (2010) didn't find agreeableness to be a significant predictor of strict parental control.

Openness to experience, which Costa and McCrae (1988) consider the fifth personality trait, includes characteristics such as imagination, originality, and broad interest (Reić Ercegovac, 2011). Accordingly, a parent who is opened to experience can accept the child's emotions and needs and be aware of his/her own shortcomings in dealing with the child (Metsapelto & Pulkkinen, 2003). Similarly, regarding Goldberg's (1992) model of personality that includes intellect instead of openness to experience, the research results showed that fathers higher on intellect are more sensitive to their children's needs (Aluja et al., 2007), stimulate them more (Prinzie et al., 2009), and use less restrictive control in discipline (Metsapelto & Pulkkinen, 2003).

Regarding child characteristics as determinants of parenting, research by Keresteš (2002) showed that parents use more controlling actions towards their sons than their daughters, and other researchers (Vučenović et al., 2015; Pozaić, 2023) concluded that fathers apply more restrictive control towards boys than girls. Keresteš (2002) found no difference in the emotionality of the parents regarding the child's gender, but Macuka (2010) found that fathers tend to show more emotional warmth towards sons than daughters. Marković (2018) found that in the upper grades of elementary school the child's age significantly negatively predicted the father's parental support, while Hanzec Marković et al. (2022) didn't find a correlation between the child's age and the perceived paternal support.

Contextual sources of stress and support as determinants of parenting in Belsky's (1984) model include partner relationship satisfaction, which refers to the subjective evaluation of the relationship with the partner. Newer models (e.g., Newland, 2015) also consider positive family functioning, including satisfaction with roles, as factors improving the quality of family interactions, promoting more sensitive, responsive, and involved parenting. Although the importance of relationship satisfaction for parental behavior has been emphasized in the past, the results regarding the effect direction are not consistent and have led to two hypotheses: the spillover hypothesis and the compensatory hypothesis. According to the spillover hypothesis, it is expected that parents who are more satisfied with their partner relationship are more supportive and sensitive to the child's needs and invest a lot in their relationship with their children compared to parents who are less satisfied with their relationship (Pedro et al., 2012). Also, they control their children less and less often apply punishments and yelling as parental actions (Chumakov & Chumakova, 2019). Aluja et al. (2007) found that parents more satisfied with their partner relationship provide their child with a lot of emotional warmth and less rejection. Conversely, when partner relationship is characterized by conflicts, parents tend to use strict discipline (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000), which they don't apply consistently, nor respond appropriately to the child's needs (Pedro et al., 2012), and they use strong psychological control over the child (Cummings et al., 2000). On the contrary, the compensatory hypothesis assumes that parents who are less satisfied with their partner relationship will support their child more and invest more in the relationship with him/her than parents who are more satisfied with their partner relationship (Nelson et al., 2009). Such results are explained by the assumption that these parents seek satisfaction in another relationship in order to compensate for the shortcomings of the relationship with the partner.

According to Belsky's (1984) model of parenting, parental functioning is multiply determined, and not all determinants have only a direct effect on parenting practices. For example, the model presumes that the broader context in which parent-child interactions take place, such as the father-mother partnership, can be influenced by the personality traits of the parents, which then indirectly affect parenting practices. In research by Olsen et al. (1999) relationship satisfaction was a mediator in the relationship between certain personality traits and maternal behavior. On the contrary, Štironja Borić et al. (2011) didn't confirm this mediational hypothesis in a sample of preschool children's fathers, as marital satisfaction didn't significantly predict either positive or negative paternal behavior.

Given the significance of parental behaviors for the child's development and well-being, it is important to recognize and investigate the factors associated with it. As assumed by the Belsky's (1984) process model of parenting, it is important to observe parenting as multiply determined, examining simultaneously different domains of parenting determinants, which is not very often in studies. In addition, given the change in the social attitudes about the father's participation in the child's upbringing and development, it is useful to examine the determinants of paternal behavior nowadays. Previous research in Croatia was predominantly focused on fathers of infants and early childhood (e.g., Pahić, 2015; Štironja Borić et al., 2011) or adolescent children (e.g., Keresteš et al., 2011; Keresteš et al., 2013) and has not paid much research attention to the fathers of primary school-aged children. Guided by research (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2014; Newland et al., 2019; Pastorelli et al., 2022; Shek et al., 2021) which shows that parental behavior depends on the wider context in which upbringing takes place, and since the research with fathers is relatively rare in Croatia, especially with children at the transition from childhood to adolescence, the purpose of the present study was to examine some determinants of parental behavior of fathers of primary school-aged children in Croatia. Following Belsky's (1984) process model of parenting, among all the proposed factors that can influence parenting behavior, we focused on paternal personality traits, relationship satisfaction, and child gender and age as possible determinants of paternal behavior.

Based on previous research, it was assumed that extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, intellect, and relationship satisfaction would be positive predictors of paternal support and negative predictors of restrictive control, while neuroticism would be a negative predictor of parental support and a positive predictor of restrictive control. In accordance with the Belsky's model, a significant mediating role of relationship satisfaction in the relationship between personality traits and paternal practices was also expected.

Methods

Participants

A total of 988 fathers of third, fourth and fifth grade elementary school students participated in the study. Fathers were between 26 and 65 years of age (M = 43.66, SD = 5.41). Most of them were married (92.7%), while a smaller part of them were in extramarital union (6.1%) or in a relationship (1.2%). The majority of fathers completed high school (61%), and many completed college or higher education (35.7%). At the time of the study, most of the fathers were employed full-time (91.5%).

Instruments

Parental Behavior Questionnaire URP 29 (Keresteš et al., 2012) was used to examine paternal support and restrictive control. The questionnaire consists of 29 items divided into seven subscales: Warmth (4 items, e.g., "I have a warm and close relationship with my child."), Autonomy (4 items, e.g., "I teach my child that it is important to fight for yourself and your ideas."), Inductive reasoning (5 items, e.g., "I explain to my child the reasons for the existence of rules."), Parental knowledge (4 items, e.g., "I usually know when my child will have a test or an oral exam at school."), Intrusiveness (4 items, e.g., "When my child does not behave the way I want, I complain and criticize him/her."), Punishment (5 items, e.g., "I slap my child when he/she misbehaves.") and Permissiveness (3 items, e.g., "I am lenient towards my child"). The subscales can be grouped into three global dimensions: Parental Support (Warmth, Autonomy, Parental Knowledge, and Inductive Reasoning), Restrictive Control (Intrusiveness and Punishment) and Permissiveness. The participants' task is to estimate the agreement with each item on a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 - not at all true, to 4 - entirely true). The total score is calculated as the average of responses on the corresponding items. In this study, Cronbach's alphas were .91 for Paternal Support, and .74 for Restrictive Control.

The IPIP15 personality questionnaire (International Personality Item Pool; Goldberg, 1999; Milas, 2007) was used to measures five personality traits, each with three items; Extraversion (e.g., "I make friends easily."), Neuroticism (e.g., "I get upset easily."), Conscientiousness (e.g., "I like order."), Agreeableness (e.g., "I empathize with others."), and Intellect (e.g., "I manage a lot of information."). The participants' task is to evaluate on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 - very inaccurate, to 5 - very accurate) the accuracy of each statement in describing them. The total score for each personality trait is formed as the average of responses on the corresponding items, after recoding the negatively oriented items. In this study, Cronbach's alphas were .68 for extraversion, .79 for neuroticism, .68 for conscientiousness, .59 for agreeableness, and .64 for intellect.

Marital/Relationship Satisfaction Scale (Brkljačić et al., 2019) was used to measure relationship satisfaction. The scale has 9 items examining communication in the relationship, respect for the views and values of the partner, joint activities, understanding and support between the partners, distribution of duties and responsibilities, intimacy, attitude towards money and material goods and, for those who have children, satisfaction with care and relationship with the children. The participants' task is to express satisfaction with each aspect of the relationship on a scale from 0 - completely dissatisfied to 10 - completely satisfied. The total score is calculated as the average of responses on all items. Cronbach's alpha in this study was .96.

Procedure

The data was collected as a part of the project “Child wellbeing in the family context (CHILD-WELL)”, financed by the Croatian Science Foundation (HRZZ-IP-2019-04-6198). Data collection was preceded by obtaining all the necessary permits, from the Ethics committee, Croatian Ministry of Science and Education, and the school principals. A total of 15 primary schools in two Croatian counties (Osijek-Baranja and Varaždin County) were included in the research. Parents/caregivers were given envelopes with participation consents and questionnaires, which they filled out at home and returned in a sealed envelope to their child's teacher. Participation was voluntary, they were guaranteed confidentiality of data and their use exclusively for research purposes.

Statistical analyses

To examine the relationships between the studied variables, descriptive statistics and Pearson's correlation coefficients among all measured variables were calculated, and finally path analysis was performed in Mplus 7. The parameter estimates were obtained using the robust maximum likelihood method, and the model fit was evaluated using recommended absolute, comparative and parsimonic fit indices: χ2, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker Lewis index) and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual). Insignificant χ2, values of RMSEA < .06, CFI & TLI > .95, and SRSM < .05 were used as indicators of a good model fit (Hu & Bentler 1999).

Results

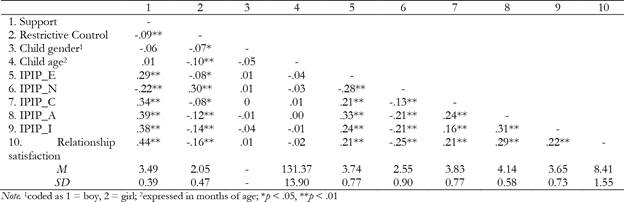

The results showed that fathers, on average, report using high levels of parental support and low restrictive control in their parenting (Table 1). They are also, on average, very satisfied with their marriages/relationships.

Correlations presented in Table 1 show that the child's age and gender were significantly correlated only with paternal restrictive control, indicating that fathers tend to use more restrictive control with boys and with younger children.

Paternal support and restrictive control were significantly correlated with all personality traits, as well as with relationship satisfaction. The direction of these significant correlations indicates that fathers who are higher on Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and Intellect, and lower on Neuroticism, and who are more satisfied with their marriages/relationships, tend to be more supportive as parents and less inclined using restrictive control.

Moreover, all correlations between personality traits and relationship satisfaction were significant, providing the basis for investigating the proposed mediational role of relationship satisfaction in the relationship between personality traits and paternal behavior.

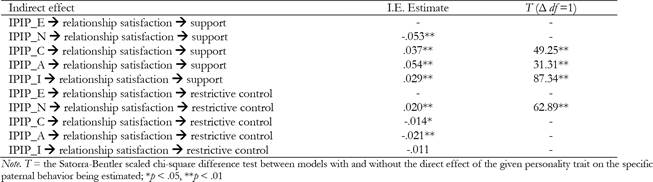

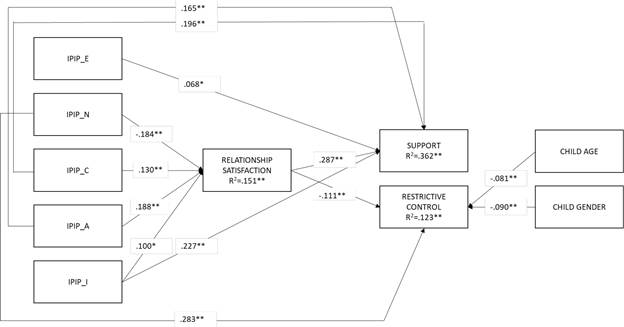

The hypothesized model was tested using path analysis. First, the partial mediation model (i.e., with both direct and indirect effects (through relationship satisfaction) of personality traits on paternal behavior) was tested. After removing insignificant paths, this model showed good fit to the data (χ2 (11) =13.437, p = .27, RMSEA = .02, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = .01). Next, the full mediation model (i.e., with direct paths from personality traits to paternal behavior being set to zero one by one) was tested. Every removal of a significant direct path from personality traits to paternal behavior resulted in a significant drop in the model fitness, and therefore the partial mediation model was kept as final (Figure 1). Indirect effect estimates and the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference tests used to compare full and partial mediation models are presented in Table 2. The strength of the indirect effects was determined according to Kenny's (2021) recommendations.

Figure 1. The final model of the relationship between child age and gender, paternal personality traits, relationship satisfaction, and paternal behavior.

Paternal support was directly positively predicted by Extraversion; both directly and indirectly, through relationship satisfaction, positively predicted by Consciousness, Agreeableness, and Intellect, and only indirectly negatively predicted by Neuroticism. All these indirect effects were small. Together, these predictors explained 36.2% of the paternal support variance.

Paternal restrictive control was negatively predicted by the child's age and gender, Consciousness and Agreeableness (with these personality traits having only small indirect effect through relationship satisfaction), and positively predicted by Neuroticism (with both direct and small indirect effect). A total of 12.3% of the paternal restrictive control variance was explained by these predictors.

Discussion and Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to examine child characteristics (gender, age), father characteristics (personality traits) and contextual sources of stress and support (relationship satisfaction) as possible determinants of parental behavior of fathers of primary school-aged children.

The results of the study showed that the child's gender and age were not significant predictors of paternal support, but they were significant negative predictors of paternal restrictive control. This is in line with the results of earlier research conducted in Croatia (e.g., Hanzec Marković et al., 2022; Marković, 2018) where the child's gender was not a significant predictor of paternal warmth or support. On the contrary, Macuka (2007) found that sons perceive paternal control as higher than daughters do. Similarly, Vučenović et al. (2015) and Pozaić (2023) found that fathers are more restrictive in raising sons than daughters. They offered an explanation that paternal behavior encourages gender-typical behaviors in children, such as encouraging independence in the upbringing of sons and encouraging caring and nurturing behaviors in the upbringing of daughters. Regarding the child's age, fathers use less restrictive control towards older children, which can be explained by the fact that older children have a greater ability to self-control their own behavior and experiences (Denissen et al., 2009) and are more emotionally mature than younger children which is why it is harder for parents to emotionally manipulate them (which is a characteristic of parental restrictive control).

Regarding paternal individual characteristics, i.e., the contribution of paternal personality traits in explaining their parenting behaviors, personality traits as hypothesized significantly predicted paternal support, while the contribution of personality traits in the explanation of restrictive control was mostly mediated by contextual determinants, i.e., relationship satisfaction.

Although the results of previous research on the relationship between extraversion and parental behavior are not consistent, many studies point to warm, caring, and nurturing parenting of extraverted individuals (Denissen et al., 2009), which is in line with the results of the present study. Extraverted parents often engage in various interpersonal relationships, are optimistic and skilled in communication, which is probably reflected in their relationship with the child. Also, Belsky and Jaffee (2006) consider parenting as a social task, which is why they expect more extraverted individuals to cope better with the parental role. In addition, the characteristics of extraversion indicate positive affect, energy, and engagement, which Belsky et al. (1995) associate with the father's "playfulness" and his positive parental involvement. Parental support being predicted by paternal conscientiousness is in line with earlier research with fathers of adolescents (Aluja et al., 2007; Denissen et al., 2009), while Losoya et al. (1997) found a significant positive correlation of parental support and conscientiousness in a sample of parents of children under the age of eight. Moreover, McCabe (2014) also found a positive association between conscientiousness and parental warmth. Highly conscientious parents maintain quality relationships with their child (Belsky & Barends, 2002), which is attributable to their tendency to self-discipline and commitment to moral principles, all for the purpose of achieving optimal developmental outcomes for their child. Also, with their determination, responsibility, and accuracy, they support the child's growth and development in a structured environment (Prinzie et al., 2009). In addition to extraversion and conscientiousness, the results of this study indicated a significant contribution of agreeableness in predicting paternal support. Such results are also consistent with the results of earlier research (Prinzie et al., 2009; Smetko, 2020). Agreeable parents are trustworthy, cooperative, and benevolent, which helps them to recognize children's needs and to be ready to respond to them adequately (Reić Ercegovac, 2011). Quality parenting requires the individual to have a great potential for establishing close and supportive interactions with the child and specific abilities and skills that are important in interpersonal relationships such as honesty, trust and willingness to help (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006). Therefore, it is not surprising that parents who are high on agreeableness support their child and develop close relationships with him/her. In accordance with the results of the present study, Aluja et al. (2007) found that paternal openness to experience predicts their emotional warmth towards their adolescent children. Bornstein et al. (2011) found a significant positive association between openness to experience and parental warmth among mothers. Research conducted with a sample of Croatian parents of children between the ages of four and seventeen also showed that parents who are more open to experience provide their child with more emotional warmth in upbringing (Smetko, 2020). These results can be explained by the fact that curious, creative, and versatile fathers establish warm and supportive relationships with their children. Because they are interested in new experiences and perspectives, they are likely to participate in the child's life with more encouragement and support compared to those parents who are reserved and skeptical of different visions (Koenig et al., 2010). Finally, as expected, neuroticism significantly and negatively predicted paternal support, which is consistent with previous research. Parents who are high on the dimension of neuroticism provide less support to children and are less sensitive to their needs, which Prinzie et al. (2009) explained by the characteristics of individuals high on this personality dimension, such as a tendency to negative mood, tension, agitation. They suggest that these parents are then preoccupied with their own inner state which makes them less sensitive and supportive of their child.

Neuroticism showed to be a significant predictor of paternal restrictive control; fathers higher on neuroticism tend to use more restrictive control with their children. Huver et al. (2010) reported that parents of adolescents who are higher on neuroticism have high expectations of their children and tend to monitor them continuously. Takahashi et al. (2017) found a significant positive association between neuroticism and parental affectionless control, characterized by low care and high control over the child. In addition, anxiety, tension, and a generally negative affect which characterize an individual high in neuroticism can be reflected in the relationship with the child in which the parent will tend to blame, embarrass the child, take an excessive interest in his/her actions, create great pressure on him/her, etc. Contrary to expectations, extraversion was not a significant predictor of paternal restrictive control. In a study by Ganiban et al. (2009), a significant negative correlation was found between adolescent parents' negativity and parental extraversion, with negativity referring to the degree to which, during interactions with the child, the parents expressed anger and coercion, which are characteristic of parental restrictive control. However, other studies did not find a connection between extraversion and parental control (Huver et al., 2010) explaining these inconsistent results by claiming that the trait extraversion is associated with affective aspects of parental behavior, while the same is not true for aspects of parental control. Conscientiousness was also not a significant predictor of restrictive control in the present study, although previous research suggested conscientiousness to be negatively related to negative control (Denissen et al., 2009; Losoya et al., 1997). Regarding agreeableness, it was expected for it to significantly predict restrictive control. For example, in Prinzie et al.'s (2004) study, higher agreeableness was associated with the use of less coercion in interactions with the child. In addition, intellect was also found to be a non-significant predictor of paternal restrictive control, which was not expected based on the available literature. The results of Denissen et al.'s (2009) research indicate the importance of openness to experience in predicting paternal restrictive control. Such results may stem from the assumption that parents who report low openness to experience hold strong traditional views that parents are "superior" to children and therefore exercise more control (McCrae, 1996).

Following Belsky's (1984) process model of parenting, the mediating role of relationship satisfaction in the relationship between personality traits and paternal behaviors was also examined. Belsky (1984) suggested that contextual sources of stress and support (e.g., marital relationship, job satisfaction, and social support) are influenced by parents' personality traits, which then exert an indirect effect on parenting behavior. The results of the present study showed that relationship satisfaction was a significant partial mediator in the relationship between conscientiousness, agreeableness, and intellect with paternal support, and a significant full mediator in the relationship between neuroticism and paternal support. Relationship satisfaction was also a significant partial mediator in the relationship between neuroticism and paternal restrictive control, and a significant full mediator in the relationship between conscientiousness and agreeableness with paternal restrictive control.

Of all the personality traits, the most consistent association with relationship satisfaction was found for the trait of neuroticism, with individuals reporting higher neuroticism being less satisfied with their relationships. In addition to its consistency, this relationship is also the largest in many studies (Heller et al., 2004; Malouff et al., 2010). As an explanation, Karney and Bradbury (1997) state that people who score high on neuroticism tend to express negative emotions when interacting with their partner, which can then be manifested through reduced satisfaction with the relationship. Characteristics of an individual high on neuroticism include anxiety and depression, which are associated with problems in marital relationships (Bond & McMahon, 1984), and which then lead to less supportive parenting (Kitzmann, 2000). For the relationship between extraversion and relationship satisfaction the results are not unambiguous. However, in accordance with the findings of the present study, Gattis et al. (2004) did not find a connection between extraversion and relationship satisfaction, explaining it by the fact that extraversion does not represent an inherently positive nor a negative trait. Regarding conscientiousness and agreeableness, Khoshdast et al. (2006) found a positive correlation between these personality traits and relationship satisfaction in parents of elementary school children. Characteristics of agreeable individuals such as respect for others, empathy, modesty, and tenderness can have a positive effect on various aspects of partner relationship, which is reflected through relationship satisfaction. Regarding openness to experience, Levy-Shiff and Israelashvili (1988) found that fathers who are more open to a variety of intellectual and emotional experiences report greater marital satisfaction.

Furthermore, as expected, relationship satisfaction positively predicted paternal support, and negatively predicted restrictive control, thus confirming the spillover hypothesis. The relationship between parental warmth and support and relationship satisfaction has been examined in numerous studies (e.g., Aluja et al., 2007; Cabrera, et al., 2014; Chumakov & Chumakova, 2019; Ganiban et al., 2009; Levy-Shiff & Israelashvili, 1988). Parents who enjoy a supportive atmosphere in their partnership and are satisfied with various aspects of the relationship have a greater capacity for establishing close and affectionate relationships with their children and a greater sensitivity to their needs (Pedro et al., 2012). Parents who are satisfied with their partner relationship control their children less often and do not use punishments as parental actions (Chumakov & Chumakova, 2019). Conversely, parents who report lower relationship satisfaction tend to be more intrusive towards their children (Brody et al., 1986) and behave less friendly towards them (Erel & Burman, 1995). In other words, a negative atmosphere and discord in the partner relationship lead to stricter discipline and blaming of the child (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000), which can then have consequences for the quality of the parent-child relationship (Erel & Burman, 1995). A meta-analysis by Krishnakumar and Buehler (2000) indicated that fathers who report greater satisfaction with their partner relationship are not prone to strict discipline nor psychological control in childrearing.

Implications and research limitations

The present study contributes to the existing literature on parenting and its determinants, especially because earlier research mostly dealt with parental behavior of parents of very young children or parents of adolescents. This study provides information about parenting in a less researched period of child development, between the ages of 8 and 13. Additionally, considering that paternity does not mean only genetic kinship, this study included not only biological fathers, but also the mothers' partners (cohabiting or in extramarital union), and divorced fathers. Furthermore, besides examining the direct effects of personality traits and relationship satisfaction on paternal behaviors, this study also examined potential mechanisms on which the relationship between these constructs is based, i.e., the mediating role of relationship satisfaction in the relationship between personality traits and paternal support and restrictive control. In terms of practical implications, the results of this study can be useful to experts who work with parents for the purpose of improving the quality of parenting behavior and parent-child relationship by improving partnership relationships. Also, from the perspective of empowerment family-oriented programs for parents, it is important to strengthen the capacity of parents, to involve them in joint decision-making and to recognize their expertise as active members in meeting the needs of their children. Thus, the results obtained in this study can be useful to practitioners who deal with empowerment parenting programs such as psychologists, sociologists, social workers, special education teachers and other helping professions. However, it is important to point out the limitations of this study that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the research used a convenience sample of fathers from Varaždin and Osijek-Baranja counties, limiting the generalizability of the obtained results. Furthermore, the participation in the research was voluntary, therefore the auto-selection of the participants resulted in the sample including fathers who perceive themselves as highly supportive and less prone to using restrictive control, and who are very satisfied with their partner relationships. Although the participation of fathers in this study is a contribution to the existing parenting literature, including both fathers and mothers would provide better understanding of family dynamics and allow for comparisons between mothers and fathers parental behaviors and its determinants, and is therefore recommended for future studies. For examining personality traits, this study used IPIP15 which measures each personality trait with only three items, which resulted in relatively low reliability coefficients for some of the subscales. Therefore, more comprehensive personality questionnaires should be used in future studies. Furthermore, in addition to examining the mediating effect of relationship satisfaction, other variables proposed by Belsky's (1984) process model of parenting which may determine parenting practices or explain the relationship between personality traits and parental behavior, such as job satisfaction and social support, should be examined in the future. Finally, it is recommended for future studies to measure predictor, mediator, and criterion variables longitudinally to track their relationship over time.