Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.30 no.4 Zaragoza oct./dic. 2016

Social determinants of mental health: a review of the evidence

Manuela Silvaa; Adriana Loureirob and Graça Cardosoa

a Chronic Diseases Research Centre (CEDOC), NOVA Medical School Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Portugal

b Centre of Studies on Geography and Spatial Planning (CEGOT), University of Coimbra. Portugal

This study was developed within the scope of the investigation project PTDC/ATP-GEO/ 4101/2012, SMAILE, Mental Health - Evaluation of the Local and Economic Determinants, funded by the Science and Technology Foundation (STF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), through the COMPETE - Operational Competitiveness Program and the doctoral fellowship SFRH/ BD/92369/2013.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: The aim of this study is to present a non-systematic narrative review of the published evidence on the association between mental health and sociodemographic and economic factors at individual- and at area-level.

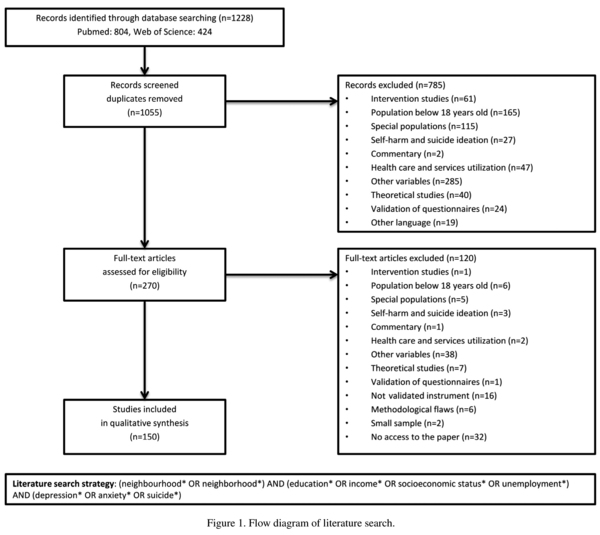

Methods: A literature search of PubMed and Web of Science was carried out to identify studies published between 2004 and 2014 on the impact of sociodemographic and economic individual or contextual factors on psychiatric symptoms, mental disorders or suicide. The results and methodological factors were extracted from each study.

Results Seventy-eight studies assessed associations between individual-level factors and mental health. The main individual factors shown to have a statistically significant independent association with worse mental health were low income, not living with a partner, lack of social support, female gender, low level of education, low income, low socioeconomic status, unemployment, financial strain, and perceived discrimination. Sixty-nine studies reported associations between area-level factors and mental health, namely neighbourhood socioeconomic conditions, social capital, geographical distribution and built environment, neighbourhood problems and ethnic composition.

Conclusions Most of the 150 studies included reported associations between at least one sociodemographic or economic characteristic and mental health outcomes. There was large variability between studies concerning methodology, study populations, variables, and mental illness outcomes, making it difficult to draw more than some general qualitative conclusions. This review highlights the importance of social factors in the initiation and maintenance of mental illness and the need for political action and effective interventions to improve the conditions of everyday life in order to improve population's mental health.

Keywords: Neighbourhood; Socioeconomic status; Depression; Anxiety; Suicide.

Introduction

Mental disorders, which include anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and alcohol and substance use, are highly prevalent and burdensome worldwide. Mental disorders were estimated to account for 12% of the global burden of disease and for 30.8% of years lived with disability1. This burden increased by 37.6% between 1990 and 20102. Therefore, tackling mental health inequalities has become a public health priority.

"Mental or psychological well-being is influenced not only by individual characteristics or attributes, but also by the socioeconomic circumstances in which persons find themselves and the broader environment in which they live"3. There is a growing interest in documenting the role of social factors on the aetiology and evolution of mental disorders, such as the relation between socioeconomic status (SES) and mental health. Also an increasing number of studies has focused on the impact of contextual characteristics (defined as neighbourhoods, workplaces, regions, states) on individual mental health and in producing health inequalities.

The aim of this study is to review the studies that examined the association between individual and community demographic and socioeconomic factors and psychiatric symptoms, mental disorders or suicide, focusing on the findings and limitations of the existing studies. Identifying the factors that influence mental health is critical for tailoring interventions and programmes that can improve mental health. This knowledge is particularly important in times of economic crisis, when the living and working conditions are substantially worsened, and social factors may have a higher negative impact on the population's mental health.

This paper intends to review empirical studies and systematic reviews assessing: (a) inequalities in the prevalence and incidence of psychiatric symptoms or common mental disorders related to sociodemographic and economic individual or contextual factors; (b) the association between suicide and sociodemographic and economic individual or contextual factors.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

A literature search was conducted in Pub-Med and Web of Science to identify the studies related to mental health (depression, anxiety and suicide) and social determinants (education, income, socioeconomic status, unemployment and neighbourhood/neighbourhood). Search was opened to studies developed in any region of the world, written in English, French, Portuguese or Spanish and published between 2004 and 2014.

More detailed information on the literature search is provided in Fig. 1.

Study selection

Title screening was first conducted to exclude irrelevant and duplicated studies. The abstracts of potential articles were reviewed by two reviewers (MS, GC). Studies were excluded if they were: (a) Opinion papers, letters to the editor, editorials, or comments; (b) Studies dealing with people below 18 years old; (c) Experimental studies about interventions addressed to reduce health inequalities; (d) Studies dealing with mental health issues among some specific populations (participants with medical conditions, in post-disaster situations, veterans, homeless...); (e) Studies in which the main health outcome variable was other than psychological distress, depression, anxiety or suicide (such as self-harm and suicide ideation, health care and services utilization or any other variables); (f) Theoretical studies or studies of validation of questionnaires; (g) Studies written in other language than English, French, Portuguese or Spanish.

Articles were reviewed in full when the abstract did not provide enough detail to make a decision. More articles were excluded in this phase if: (a) A validated screening or diagnostic instrument was not used; (b) Methodological flaws were detected (no statistical analysis described; outcome not clearly defined); (c) The sample was too small (fewer than 50 participants); (d) We did not have access to the full paper.

Data collection

The results and methodological factors, including objective(s), definition of sample, location and follow-up period, study design, mental health instrument used or source of data, outcome variable, determinant measured and, statistical methods were extracted from each study. A table with the results was constructed (Table 1). The determinant measured was categorized into two types: individual factor (demographic or socioeconomic) and neighbourhood characteristic. The outcome variable was categorized into three types: mental health or mental disorders, common mental disorders, and suicide.

Official, ethical approval was not requested in view of the nature of this study.

Results

The electronic search identified 1228 titles and 150 documents were accepted. We categorized studies according to the outcome measure, and divided them in studies examining the association of social factors with mental health or mental disorders (34 studies), common mental disorders (94 studies), and suicide (22 studies). We grouped the studies according to the independent variable (individual demographic and socioeconomic factors or neighbourhood characteristics). Thirtynine studies were conducted in Europe, 67 in North America, 9 in South America, 5 in Africa, 18 in Asia, 8 in Australia, and one in multiple continents. Three of the studies were systematic reviews.

Findings by exposure are briefly summarized below and notable findings are highlighted.

Review of studies on the social determinants of mental health

We included in this category 34 studies whose outcome measure was "psychological distress", "poor mental health" or "mental disorder". The independent variables were indicators of individual socioeconomic status or characteristics of the context. The size of the samples varied between n = 143 and n = 4.5 million. Thirteen studies were conducted in Europe, 12 in North America, 1 in Africa, 4 in Asia, and 3 in Australia. One was a systematic review. Five studies used the WHO-5 Well-being Index, 3 the CIDI, 3 the SF-36, and 3 used the GHQ, among other mental health instruments. Most of the studies performed multivariable statistical analysis, with adjustment for covariates, and some of them used multilevel models.

Individual demographic and socioeconomic factors

Cross-sectional panel surveys or nationally representative epidemiological surveys identified risk factors for mental health problems or mental disorders: female gender4, younger age4, lower socioeconomic status5-7, lower income5,8,9, lower job satisfaction9, food insufficiency10, being an immigrant from a low- or middle-income country8, interpersonal adversity in childhood7, feeling powerlessness8, negative life events8,11, lack of social/emotional support5,7,8,11,12, and living alone4 were found to be associated with mental health problems or mental disorders, although the directionality of the association is unclear. In the study conducted by Mundt et al.4 in disadvantaged urban areas, background of migration, low income and educational level were not associated with poor mental health.

Cross-sectional studies cannot distinguish whether these risk factors are associated with the development of new episodes of mental disorders, with increased duration of episodes, or both. Measurement of incidence eliminates the chronicity, selection, and drift interpretation, allowing focus on aetiology, but only a few longitudinal studies were found on this issue.

In the longitudinal studies reviewed the factors associated with worse psychological health over time were female gender13, lower job satisfaction13, age lower than 55 years13, living in common-law relationships or being widowed13, lower socioeconomic status14, lower income13, and financial concerns14,15. Caron et al.13, in Canada, found that participants whose primary language was neither French nor English were less at risk than Fran-cophones or Anglophones for developing affective (OR = 0.43) and anxiety disorders (OR = 0.40), or for any disorders (OR = 0.45), with the exception of substance dependence.

Neighbourhood characteristics

Some of the studies reviewed aimed to understand if associations between neighbourhood sociodemographic characteristics and individual symptoms or disorders reflect the characteristics of the individuals who reside in the neighbourhood (compositional) or the neighbourhood characteristics themselves (contextual). The results are conflicting: a cross-sectional study concluded that the chief determinants of current mental health and well-being were those reflecting individual level attributes and perceptions11, while others suggested that the places in which people live affect their mental health9,16-18.

Socioeconomic composition

In other studies, neighbourhood deprivation predicted mental health status, particularly on poorer individuals16, or predicted psychosis and depression, particularly paranoid ideation19. On the contrary, Gale et al.18 found no association between area-level deprivation and mental wellbeing. Fone et al.17 found that the adverse effect of income inequality on mental health starts to operate at the larger regional level, and that income inequality at neighbourhood level was associated with better mental health in low-deprivation neighbourhoods. An ecological study20 concluded that in neighbourhoods with less social contacts and with a higher proportion of jobless persons the admission rates for schizophrenia and depression increased.

Some prospective studies also explored the impact of context on mental disorders. Neighbourhood deprivation was associated with worse mental health14, increasing psychiatric medication prescription21, and higher risk of being hospitalised for mental disorder22, independent of individual-level sociodemographic characteristics. Hamoudi and Dowd23 concluded that housing market volatility may influence the psychological and cognitive health of older adults. Another study24 provided little support for social causation in neighbourhood health associations and suggested that correlations between neighbourhoods and health may develop via selective residential mobility.

We found one systematic review on the associations between ethnic density and mental disorders25. The "ethnic density hypothesis" is a proposition that members of ethnic minority groups may have better mental health when they live in areas with higher proportions of people of the same ethnicity. Shaw et al.25 concluded that protective associations between ethnic density and diagnosis of mental disorders were most consistent in older US ecological studies of admission rates. Among more recent multilevel studies, there was some evidence of ethnic density being protective against depression and anxiety for African American people and Hispanic adults in the USA. However, Hispanic, Asian-American and Canadian "visible minority" adolescents have higher levels of depression at higher ethnic densities. Studies in the UK showed mixed results, with evidence for protective associations most consistent for psychoses.

• Social environment

Social capital is defined as the resources available to individuals and to society through social relationships26, "the features of social organization, such as civic participation, norms of reciprocity, and trust in others, that facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit"27.

Some of the empirical studies reviewed assessed the association between social capital and mental health. Social capital may affect mental health in different ways, through its "structural" (connectedness, membership of organisations) or "cognitive" (trust, sense of belonging, and shared values) components. High levels of structural social capital28-31 and high levels of cognitive social capital18,30 were associated with lower risk of mental health distress or disorder after taking into account potential individual confounders. People who reported fewer neighbourhood problems had higher levels of mental wellbeing, independently of individual factors18. The perception of severe problems in the community28,32, exposure to violence and negative life events33, and high frequency levels of discrimination34 were associated with higher levels of psychological distress. Perceived neighbourhood satisfaction35 and stress-buffering mechanisms in the neighbourhood33 were associated with a lower likelihood of disorders. Higher workplace social capital was associated with lower odds of poor mental health in a study among Chinese employees36.

Physical environment / geographical location

Higher neighbourhood average household occupancy and churches per capita were associated with a lower likelihood of disorders33. Factors such as noise, air quality, low quality of drinking water, crime and/or violence, rubbish and traffic congestion were associated with worst mental health across Europe37. Architectural features of the front entrance such as porches that promote visibility from a building's exterior were positively associated with perceived social support, which in turn was associated with reduced psychological distress after controlling for demographics38. In a longitudinal study, neighbourhood residential instability was associated with higher levels of alcoholic and depressive symptomatology in women39.

Review of studies on the social determinants of common mental disorders

We grouped in this category 94 studies whose outcome was assessed using a validated screening or diagnostic instrument allowing a common mental disorder (depressive or anxiety disorder) diagnosis to be made. The size of the samples ranged between n = 112 and n = 237,469. Sixteen studies were conducted in Europe, 52 in North America, 7 in South America, 4 in Africa, 10 in Asia, 2 in Australia, and one in multiple continents. Two of the studies were systematic reviews. Most of the studies used the CES-D (41), and others used the CIDI (8), the GDS-30 (8), the GHQ (5), the BDI (3), or the HADS (3), among other mental health instruments. Almost all the studies performed multivariable statistical analysis, with adjustment for covariates, and some of them used multilevel models.

Individual demographic and socioeconomic factors

We found a systematic mapping of research on postnatal depression and poverty in low- and lower middle-income countries40. The authors state that research is limited, but has recently expanded, and that it is dominated by studies that consider whether poverty is a risk factor for postnatal depression. They found that income, socio-economic status and education are all inconsistent risk factors for postnatal depression. Coast et al.40 argue that to understand the scale and implications of postnatal depression in low- and lower middle-income countries research has to take into account neighbourhoods, communities, and localities.

Several cross-sectional studies assessed which individual demographic and socioeconomic factors were associated with an increased prevalence of common mental disorders. Female gender41-48, not being married41,42,44,46,48-52, being married45, higher age42,52, household food insufficiency53,54, less favourable housing condition54,55, low social position43,56, lower education56-58, unemployment52,58-60, low income42,44,45,49,52,55,57,58,61-64, financial strain49, less income stability56, negative subjective health48,52,59,62, lower overall health status42, having functional impairment62, rural residency47,52,65, no religiosity52, lower social stability66, being a victim of sexual violence59, psychological violence during childhood59, lack of support network49,59,61,67,68, poorer quality of life42, perceived discrimination (racial or other)54,69, perceived stress58, a poor sense of mastery/ control63,70, and feeling more lonely47,55 were variables that remained significantly associated with an increased prevalence of common mental disorders after adjustments. St John et al.62 found no rural-urban differences associated with depressive symptoms. Depression is a severe problem in the unemployed population, particularly among the long-term unemployed60. In a population-based register study in Finland, among those with no previous inpatient or antidepressant treatment, all measures of low social position and not living with a partner predicted admission for depression71.

Some cross-sectional studies focused specifically in identifying protective and risk factors associated with common mental disorders in immigrants. Two studies conducted in the US compared native-born and immigrant groups: the first found that, controlling for other predictors, the likelihood of depression was much higher among black women who were US born than among black women who were African born or Caribbean born72, and the second showed that a native-born Mexican American group was not significantly different from an immigrant group on measures of depression, health status, life satisfaction, or self-esteem73. Another study, conducted among Gujarati-speaking immigrants in Atlanta74, concluded that poorer health and a more traditional ethnic identity were related to depressive symptoms.

In prospective studies the following factors were independently associated with higher rates of common mental disorders: female gender75, socioeconomic disadvantage76, low level of education75, lower subjective social status77, mortgage delinquency78, home foreclosure79, financial strain80, marital conflict and marital disruption81, and perceived discrimination82-84. Depressed individuals with low socioeconomic status appear disproportionately likely to experience multiple risk factors of long-term depression85. In one study, only subjective financial difficulties at baseline were independently associated with depression at follow-up, supporting the view that apart from objective measures of socio-economic position, more subjective measures might be equally important from an aetiological or clinical perspective86.

A study in the US suggested that the rise in the prevalence of depression in the prior quarter century among middle-aged females is due to increasing chronicity87. Another study suggests that the causal relationship hypothesized in prior studies -that perceived social position affects health- does not necessarily hold in empirical models of reciprocal relationships88. Higher SES prior to job loss is not uniformly associated with fewer depressive symptoms: higher education and lower prestige appear to buffer the health impacts of job loss, while financial indicators do not89.

Neighbourhood characteristics

We found a systematic review of the published literature on the associations between neighbourhood characteristics (neighbourhood socioeconomic status, physical conditions, services/amenities, social capital, social disorder) and depression in adults90. Evidence generally supports harmful effects of social disorder and, to a lesser extent, suggests protective effects for neighbourhood socioeconomic status. Few investigations have explored the relations for neighbourhood physical conditions, services/amenities, and social capital, and less consistently point to salutary effects. Kim90 argues that the unsupportive findings may be attributed to the lack of representative studies within and across societies or to methodological gaps, including lack of control for other neighbourhood/non-neighbourhood exposures and lack of implementation of more rigorous methodological approaches.

Socioeconomic composition

Some cross-sectional studies suggest that neighbourhood low-SES49,91, material deprivation92,93, living in an area with high unemployment94, residential mobility92, residential stability95, higher population density96, urban neighbourhoods97, perceived traffic stress98, neighbourhood walkability99, poor quality built environment100,101, village infrastructure deficiency102, neighbourhood violent crime and poorer perceptions of neigh-bourhood safety103 are associated with increased depressive symptoms or depression, independent of individual level characteristics. However, other studies suggest that individual level characteristics explain away the association between neighbourhood level factors and depression48,57,95,96,104. Higher household income may help to reduce symptoms of depression by reducing financial stress and strengthening social support even within neighbourhoods with high concentrations of poverty, but it does not protect those residing in a high poverty community from distress associated with neighbourhood disorder or experiences of discrimination105.

In an ecological study, the significant risk factors found for hospitalization included unemployment, poverty, physician supply, and hospital bed supply, and the significant protective factors were rurality, economic dependence, and housing stress106.

Two cross-sectional studies included in this review107,108 demonstrated that living in a neighbourhood with a higher percentage of residents of the same ethnicity was associated with depression.

Data from some prospective studies indicate socioeconomic status of neighbourhood of residence to be associated with incidence or worsening of depression independent of individual socioeconomic status and other individual covariates109, while others did not support this association110,111. In multivariable models that adjusted for individual-level covariates, the neighbourhood characteristics shown to represent risk factors for common mental disorders were increases in neighbourhood-level foreclosure112, economic disadvantage/deprivation113-116, exposure to neighbourhood unemployment earlier in life117, perceived community violence113, social disorder114, and urban neighbourhoods118. In another study, living in a socially advantaged neighbourhood, with cultural services, near a park and having a local health service nearby were associated with lower risk of depression119.

Some studies examined the impact of income inequality on mental health. One cross-sectional study found significant associations between neighbourhood inequality and depression120, and another found higher depressive symptoms in countries with greater income inequality and with less individualistic cultures63, independently of individual level effects. A longitudinal study found that income inequality did not correlate significantly with the presence of depressive symptoms115.

Social environment

Cross-sectional studies suggest that neighbourhood-level social capital121,122 and its dimensions of availability and satisfaction with community services102,123, high collective efficacy124 and community participation124 reduce the likelihood of depressive symptoms. One study found that major depression was not associated with social capital125. In an instance of the "dark side" of social capital, Takagi et al.126 found that stronger social cohesion increased depressive symptoms for residents whose hometown of origin differed from the communities where they currently resided. Both neighbourhood disorder and community cohesion were related to PTSD symptoms after controlling for trauma exposure127. Life events mediate the relation between neighbourhood characteristics and depression128. Teychenne et al.129investigated the contribution of perceived neighbourhood factors in mediating the relationship between education and women's risk of depression, and they found that interpersonal trust was the only neighbourhood characteristic which partly mediated this relationship.

In the longitudinal studies reviewed, lower levels of social cohesion130, of cognitive social capital131, and of aesthetic quality130, and higher levels of violence130,132 were positively associated with incident depression. People who trusted their neighbours were less likely to develop major depression, but the association became non-significant after excluding participants with major depression at the baseline131. In another study, stronger perceived neighbourhood homogeneity was inversely associated with depressive mood, but, when participants who reported a depressive mood at baseline were excluded, stronger perceived heterogeneous network was inversely associated with depressive mood133. Both social support and neighbourhood collective efficacy moderated the effect of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms82.

Review of studies on the social determinants of suicide

In this category we included 22 studies. 10 of these studies were conducted in Europe, 3 in North America, 2 in South America, 4 in Asia, and 3 in Australia. The studies consisted of individual-level evidence (case-control or cohort studies) or aggregate (ecological) studies.

Individual demographic and socioeconomic factors

Individual-level evidence shows that risk factors for suicide are male gender134, older age134,135, being unmarried/divorced/widowed136, low education137-139, socioeconomic disadvantage138,140,141, unemployment135, increasing levels of firearm availability135, and immigration142. In a study describing the characteristics of elderly suicide victims139, suicide was associated with living in a one-person household (OR = 2.4, p < 0.01), not having economic troubles (OR = 6.1, p < 0.01), having seen a doctor in the past month (OR = 2.4, P < 0.01) and living in a residential facility (OR = 2.6, p < 0.05).

Neighbourhood characteristics

Some studies have shown associations between suicide rates and indices of area deprivation137,143-145. However, O'Reilly et al.141 suggested that differences in rates of suicide between areas are predominantly due to population characteristics rather than to area-level factors.

Individual-level and population-based evidence suggested that low social capital146,147, low linking social capital148, unemployment rate149, the proportion of indigenous population149, the proportion of population with low individual income149 and income inequality150, particularly for those aged 15-60151 were significantly and positively associated with suicide. Another study found no statistically significant independent association of a structural measure of neighbourhood social capital (volunteerism) with suicide152.

In the studies reviewed on the geographical distribution, suicide rates were higher in rural areas134,137,140. In a study in the US, rural decedents were less likely to be receiving mental health care and more likely to use firearms to commit suicide153. A study in England and Wales154 found higher rates of suicide in inner cities, but largely explained by the socioeconomic characteristics of these areas, and in coastal regions, particularly those in more remote regions. In Croatia, Karlović et al.155 found a higher average suicide rate in the continental area than in the Mediterranean area.

Discussion

Main findings

The systematic reviews included in this study showed a) mixed results on the associations between ethnic density and mental disorders, b) limited research on the association between poverty and postnatal depression in low- and lower middle-income countries, with inconsistent results, and c) support for the harmful effect of neighbourhood social disorder and, to a lesser extent, protective effect of neighbourhood socioeconomic status on depression.

This non-systematic narrative review documents a growing body of literature investigating the social determinants of mental health: 47 of the 150 studies included (31,3%) were published in 2013 and 2014, with only 17 (11,3%) of the studies published in 2004 and 2005, the two first years of this review.

Seventy-eight studies reported associations between individual-level factors and mental health. Given the large number of exposures considered in this review, some exposure-outcome pairs were examined by only a single study. The main factors shown to have a statistically significant independent association with worse mental health were low income (17 studies), marital status/not living with a partner (16 studies), lack of emotional/social support (10), female gender (9), low level of education (9), low socioeconomic status (7), unemployment (5), financial strain (5), perceived discrimination (5), negative subjective health (4), loneliness (4), low subjective social status (3), deteriorated housing (3), higher age (3) and negative life events (3). Level of education, parenthood, rural-urban differences, low socioeconomic position and race were not associated with mental health outcomes in one study for each determinant.

Sixty-nine studies reported associations between area-level factors and mental health, 23 focusing on social capital, 36 on neighbourhood socioeconomic conditions, 15 on geographical distribution and built environment, 9 on exposure to neighbourhood problems, and 2 on ethnic composition. The large majority (12 of 14-86%) of the studies assessing "structural" aspects of social capital found a statistically significant association between measures of low social capital and poor mental health. Ninety-two percent (12 of 13) of the studies assessing "cognitive" aspects of social capital found a statistically significant association between low social capital and poor mental health. Statistically significant positive associations were found in 24 (82.8%) of the 29 studies assessing the relationship between measures of neighbourhood economic disadvantage and psychological distress, depression and suicide. Income inequality was a risk factor for suicide in 2 studies, but results on the association with poor mental health and depression were conflicting. Unemployment rate emerged as a risk factor for poor mental health and suicide in 6 studies. Being exposed to neighbourhood problems was associated with higher levels of psychological distress, depression and suicide in 11 studies, while the presence of stress-buffering mechanisms was statistically significantly and negatively associated with mental disorders. Urban neighbourhoods were associated with depression in 4 studies, but rural areas were associated with higher suicide rates than urban areas in other 4 studies. Poor quality built environment also emerged as a risk factor for depression in 3 studies, while neighbourhood walkability and living near a park were protective factors.

Limitations

This review has some limitations, at review-level and at study- and outcome-level.

Literature search was limited to articles focusing on individual and contextual determinants, and this search strategy may have contributed to an incomplete retrieval of studies. Several exclusion criteria were established in order to reduce the heterogeneity of studies and to make it possible to extract some conclusions, and this further narrowed the studies included. We had no access to 31 of the 266 articles assessed for eligibility, and that was a reason for exclusion.

We included in the review the studies identified by the search strategy, but factors such as publication bias and selective reporting may contribute to a distorted perception of the results.

There was large heterogeneity between studies concerning study design and populations, determinants, outcome and instruments used. This heterogeneity only allows a few descriptive findings.

Future research direction

Further empirical studies on social inequalities in health are needed to make sense of the mixed research findings, to understand the pathways through which they influence health, and to find out ways of reducing their magnitude.

Two main mechanisms have been posited in understanding the link between mental illness and poor social circumstances: social causation and social selection. According to the social causation hypothesis, socioeconomic standing has a causal role in determining health or emotional problems. Social selection hypothesis posits that genetically predisposed individuals with worse physical or emotional health may "drift down" the socioeconomic hierarchy or fail to rise in socioeconomic standing as would be expected on the basis of familial origins or changes in societal affluence. Longitudinal studies, with multiple time point measures, are much needed in the future to clarify the causal direction between social determinants and mental health.

The study of the associations between contextual SES and mental health also needs more powerful studies, using multilevel analyses and establishing mediating pathways and effect-modifying factors, in order to disentangle the individual effect from the neighbourhood effect on health.

Conclusion

The goal of this literature review was to identify the relevant published evidence on the associations between social determinants and mental health. These disorders are highly prevalent, have severe consequences, and it is particularly important to improve our understanding of modifiable risk factors that may help to advance preventive efforts.

For many decades, studies have shown that mental health is the complex outcome of numerous biological, psychological and social factors, involving contextual factors beyond the individual. Despite changes in concepts and methods used to define cases and measure socioeconomic status, the studies reviewed suggest that exposure to a wide range of social stressors continues to play an important role in the aetiology and the course of mental health problems and disorders. Higher rates of mental disorders are associated with social disadvantage, especially with low income, limited education, occupational status and financial strain. Lack of social support, high-demand or low control over work, critical life events, unemployment, adverse neighbourhood characteristics, and income inequality were also identified as psychosocial risks that increase the chances of poor mental health. Importantly, this review highlighted some important protective factors: having trust in people, feeling safe in the community, and having social reciprocity is associated with lower risk of mental health distress.

Our results suggest that both individuals and neighbourhoods need to be targeted in order to enhance mental health. Saraceno156 argued that, in parallel to the classical biopsychosocial etiological hypothesis, an identical paradigm for mental health intervention is needed: "The social dimension of mental illness should be an intrinsic component of intervention and not just a concession in etiological modelling"156. In fact, the present review suggests that ameliorating the economic situation of individuals, enhancing community connectedness, and combating neighbourhood disadvantage and social isolation may improve population's mental health. These results may be relevant to healthcare providers and to policy makers, and should be taken into account when designing policies and interventions aimed at improving treatment services, preventing mental disorders, and promoting mental health in different communities.

Acknowledgements

We thank the researchers and consultants of the project SMAILE, Study on Mental Health - Assessment of the Impact of Local and Economic Conditioners (PTDC/ATP-GEO/4101/2012) - Benedetto Saraceno, Carla Nunes, Cláudia Costa, Joana Lima, João Ferrão, José Miguel Caldas de Almeida, Maria do Rosário Partidário, Paula Santana, and Pedro Pita Barros - for their contributions during the development of the project.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

1. World Health Organization. The World Health Report: 2001: Mental health - new understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [ Links ]

2. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013; 382(9904): 1575-86. [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. Risks to Mental Health: an overview of vulnerabilities and risk factors. Background paper by WHO Secretariat for the development of a comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [ Links ]

4. Mundt A, Kliewe T, Yayla S, Ignatyev Y, Busch MA, Heimann H, et al. Social characteristics of psychological distress in disadvantaged areas of Berlin. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014; 60(1): 75-82. [ Links ]

5. Lam CW, Boey KW. The psychological well-being of the Chinese elderly living in old urban areas of Hong Kong: a social perspective. Aging Ment Health. 2005; 9(2): 162-6. [ Links ]

6. Meyer OL, Castro-Schilo L, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: a model of socioeconomic status, neighborhood safety, and physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2014; 104(9): 1734-41. [ Links ]

7. Oshio T, Umeda M, Kawakami N. Impact of interpersonal adversity in childhood on adult mental health: how much is mediated by social support and socio-economic status in Japan? Public Health. 2013; 127(8): 754-60. [ Links ]

8. Dalgard OS, Thapa SB, Hauff E, McCubbin M, Syed HR. Immigration, lack of control and psychological distress: findings from the Oslo Health Study. Scand J Psychol. 2006; 47(6): 551-8. [ Links ]

9. Gruebner O, Khan MM, Lautenbach S, Müller D, Krämer A, Lakes T, et al. Mental health in the slums of Dhaka-a geoepidemiological study. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12: 177. [ Links ]

10. Sorsdahl K, Slopen N, Siefert K, Seedat S, Stein DJ, Williams DR. Household food insufficiency and mental health in South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011; 65(5): 426-31. [ Links ]

11. Kelly BJ, Lewin TJ, Stain HJ, Coleman C, Fitzgerald M, Perkins D, et al. Determinants of mental health and well-being within rural and remote communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011; 46(12): 1331-42. [ Links ]

12. Caron J, Latimer E, Tousignant M. Predictors of psychological distress in low-income populations of Montreal. Can J Public Health. 2007; 98 Suppl 1: S35-44. [ Links ]

13. Caron J, Fleury MJ, Perreault M, Crocker A, Tremblay J, Tousignant M, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders, and use of mental health services in the epidemiological catchment area of Montreal South-West. BMC Psychiatry. 2012; 12: 183. [ Links ]

14. Santiago CD, Wadsworth ME, Stump J. Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. J Economic Psychol. 2011; 32(2): 218-30. [ Links ]

15. Prady SL, Pickett KE, Croudace T, Fairley L, Bloor K, Gilbody S, et al. Psychological distress during pregnancy in a multi-ethnic community: findings from the born in Bradford cohort study. PLOS ONE. 2013; 8(4): e60693. [ Links ]

16. Fone D, Dunstan F, Williams G, Lloyd K, Palmer S. Places, people and mental health: a multilevel analysis of economic inactivity. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64(3): 633-45. [ Links ]

17. Fone D, Greene G, Farewell D, White J, Kelly M, Dunstan F. Common mental disorders, neighbourhood income inequality and income deprivation: small-area multilevel analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013; 202(4): 286-93. [ Links ]

18. Gale CR, Dennison EM, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Neighbourhood environment and positive mental health in older people: the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Health Place. 2011; 17(4): 867-74. [ Links ]

19. Wickham S, Taylor P, Shevlin M, Bentall RP. The impact of social deprivation on paranoia, hallucinations, mania and depression: the role of discrimination social support, stress and trust. PLoS One. 2014; 9(8): e105140. [ Links ]

20. Simone C, Carolin L, Max S, Reinhold K. Associations between community characteristics and psychiatric admissions in an urban area. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013; 48(11): 1797-808. [ Links ]

21. Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Neighborhood deprivation and psychiatric medication prescription: a Swedish national multilevel study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011; 21(4): 231-7. [ Links ]

22. Sundquist K, Ahlen H. Neighbourhood income and mental health: a multilevel follow-up study of psychiatric hospital admissions among 4.5 million women and men. Health Place. 2006; 12(4): 594-602. [ Links ]

23. Hamoudi A, Dowd JB. Housing wealth, psychological well-being, and cognitive functioning of older Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014; 69(2): 253-62. [ Links ]

24. Jokela M. Are neighborhood health associations causal? A 10-year prospective cohort study with repeated measurements. Am J Epidemiol. 2014; 180(8): 776-84. [ Links ]

25. Shaw RJ, Atkin K, Bécares L, Albor CB, Stafford M, Kiernan KE, et al. Impact of ethnic density on adult mental disorders: narrative review. Br J Psychiatry. 2012; 201(1): 11-9. [ Links ]

26. Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002; 56(9): 647-52. [ Links ]

27. Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997; 87(9): 1491-8. [ Links ]

28. Brisson D, Lopez A, Yoder J. Neighborhoods and mental health trajectories of low-income mothers. J Community Psychol. 2014; 42(5): 519-529. [ Links ]

29. Lofors J, Sundquist K. Low-linking social capital as a predictor of mental disorders: a cohort study of 4.5 million Swedes. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64(1): 21-34. [ Links ]

30. Phongsavan P, Chey T, Bauman A, Brooks R, Silove D. Social capital, socio-economic status and psychological distress among Australian adults. Soc Sci Med. 2006; 63(10): 2546-61. [ Links ]

31. Sundquist J, Hamano T, Li X, Kawakami N, Shiwaku K, Sundquist K. Neighborhood linking social capital as a predictor of psychiatric medication prescription in the elderly: a Swedish national cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014; 55: 44-51. [ Links ]

32. Gary TL, Stark SA, LaVeist TA. Neighborhood characteristics and mental health among African Americans and whites living in a racially integrated urban community. Health Place. 2007; 13(2): 569-75. [ Links ]

33. Stockdale SE, Wells KB, Tang L, Belin TR, Zhang L, Sherbourne CD. The importance of social context: neighborhood stressors, stress-buffering mechanisms, and alcohol, drug, and mental health disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 65(9): 1867-81. [ Links ]

34. Ajrouch KJ, Reisine S, Lim S, Sohn W, Ismail A. Perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress: does social support matter? Ethn Health. 2010; 15(4): 417-34. [ Links ]

35. Kamimura A, Christensen N, Tabler J, Prevedel JA, Ojha U, Solis SP, et al. Depression, somatic symptoms, and perceived neighborhood environments among US-born and non-US-born free clinic patients. South Med J. 2014; 107(9): 591-6. [ Links ]

36. Gao J, Weaver SR, Dai J, Jia Y, Liu X, Jin K, et al. Workplace social capital and mental health among Chinese employees: a multi-level, cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014; 9(1): e85005. [ Links ]

37. Shiue I. Neighborhood epidemiological monitoring and adult mental health: European Quality of Life Survey, 2007-2012. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015; 22(8): 6095-103. [ Links ]

38. Brown SC, Mason CA, Lombard JL, Martinez F, Plater-Zyberk E, Spokane AR, et al. The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: the role of "eyes on the street". J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009; 64(2): 234-46. [ Links ]

39. Buu A, Wang W, Wang J, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Changes in women's alcoholic, antisocial, and depressive symptomatology over 12 years: a multilevel network of individual, familial, and neighborhood influences. Dev Psychopathol. 2011; 23(1): 325-37. [ Links ]

40. Coast E, Leone T, Hirose A, Jones E. Poverty and postnatal depression: a systematic mapping of the evidence from low and lower middle income countries. Health Place. 2012; 18(5): 1188-97. [ Links ]

41. Chou KL, Cheung KC. Major depressive disorder in vulnerable groups of older adults, their course and treatment, and psychiatric comorbidity. Depress Anxiety. 2013; 30(6): 528-37. [ Links ]

42. Dong X, Chen R, Li C, Simon MA. Understanding Depressive Symptoms Among Community-Dwelling Chinese Older Adults in the Greater Chicago Area. J Aging Health. 2014; 26(7): 1155-71. [ Links ]

43. Glei DA, Goldman N, Liu IW, Weinstein M. Sex differences in trajectories of depressive symptoms among older Taiwanese: the contribution of selected stressors and social factors. Aging Ment Health. 2013; 17(6): 773-83. [ Links ]

44. Gorn SB, Sainz MT, Icaza MEMM. Variables demográficas asociadas con la depresión: diferencias entre hombres y mujeres que habitan en zonas urbanas de bajos ingresos. Salud Mental. 2005; 28(6): 33-40. [ Links ]

45. Oliveira MF, Bezerra VP, Silva AO, Alves M do S, Moreira MA, Caldas CP. Sintomatologia de depressão autorreferida por idosos que vivem em comunidade. Ciência Saúde Colet. 2012; 17(8): 2191-8. [ Links ]

46. Wang JK, Su TP, Chou P. Sex differences in prevalence and risk indicators of geriatric depression: the Shih-Pai community-based survey. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010; 109(5): 345-53. [ Links ]

47. Wang Z, Shu D, Dong B, Luo L, Hao Q. Anxiety disorders and its risk factors among the Sichuan empty-nest older adults: a cross-sectional study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013; 56(2): 298-302. [ Links ]

48. Watson KT, Roberts NM, Saunders MR. Factors Associated with Anxiety and Depression among African American and White Women. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012; 2012: 432321. [ Links ]

49. Kingston S. Economic adversity and depressive symptoms in mothers: Do marital status and perceived social support matter? Am J Community Psychol. 2013; 52(3-4): 359-66. [ Links ]

50. Joutsenniemi K, Martelin T, Martikainen P, Pirkola S, Koskinen S. Living arrangements and mental health in Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60(6): 468-75. [ Links ]

51. Rimehaug T, Wallander J. Anxiety and depressive symptoms related to parenthood in a large Norwegian community sample: the HUNT2 study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010; 45(7): 713-21. [ Links ]

52. Beutel ME, Weidner K, Schwarz R, Brähler E. Age-related complaints in women and their determinants based on a representative community study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004; 117(2): 204-12. [ Links ]

53. German L, Kahana C, Rosenfeld V, Zabrowsky I, Wiezer Z, Fraser D, et al. Depressive symptoms are associated with food insufficiency and nutritional deficiencies in poor community-dwelling elderly people. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011; 15(1): 3-8. [ Links ]

54. Siefert K, Finlayson TL, Williams DR, Delva J, Ismail AI. Modifiable risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in low-income African American mothers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007; 77(1): 113-23. [ Links ]

55. Tong HM, Lai DW, Zeng Q, Xu WY. Effects of social exclusion on depressive symptoms: elderly Chinese living alone in Shanghai, China. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2011; 26(4): 349-64. [ Links ]

56. Hamad R, Fernald LC, Karlan DS, Zinman J. Social and economic correlates of depressive symptoms and perceived stress in South African adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008; 62(6): 538-44. [ Links ]

57. Henderson C, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR Jr, Kiefe CI, West D, Williams DR. Neighbourhood characteristics, individual level socioeconomic factors, and depressive symptoms in young adults: the CARDIA study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005; 59(4): 322-8. [ Links ]

58. Van der Waerden JE, Hoefnagels C, Hosman CM, Jansen MW. Defining subgroups of low socioeconomic status women at risk for depressive symptoms: the importance of perceived stress and cumulative risks. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014; 60(8): 772-82. [ Links ]

59. Illanes E, Bustos L, Vizcarra MB, Muñoz S. Violencia y factores sociales asociados a salud mental en mujeres de la ciudad de Temuco. Rev Med Chil. 2007; 135(3): 326-34. [ Links ]

60. Stankunas M, Kalediene R, Starkuviene S, Kapustinskiene V. Duration of unemployment and depression: a cross-sectional survey in Lithuania. BMC Public Health. 2006; 6: 174. [ Links ]

61. Kim J, Richardson V, Park B, Park M. A multilevel perspective on gender differences in the relationship between poverty status and depression among older adults in the United States. J Women Aging. 2013; 25(3): 207-26. [ Links ]

62. St John PD, Blandford AA, Strain LA. Depressive symptoms among older adults in urban and rural areas. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006; 21(12): 1175-80. [ Links ]

63. Steptoe A, Tsuda A, Tanaka Y, Wardle J. Depressive symptoms, socio-economic background, sense of control, and cultural factors in university students from 23 countries. Int J Behav Med. 2007; 14(2): 97-107. [ Links ]

64. Tannous L, Gigante LP, Fuchs SC, Busnello ED. Postnatal depression in Southern Brazil: prevalence and its demographic and socioeconomic determinants. BMC Psychiatry. 2008 3; 8: 1. [ Links ]

65. Humeniuk E, Bojar I, Owoc A, Wojtyła A, Fronczak A. Psychosocial conditioning of depressive disorders in post-menopausal women. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011; 18(2): 441-5. [ Links ]

66. German D, Latkin CA. Social stability and health: exploring multidimensional social disadvantage. J Urban Health. 2012; 89(1): 19-35. [ Links ]

67. McKinnon B, Harper S, Moore S. The relationship of living arrangements and depressive symptoms among older adults in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: 682. [ Links ]

68. Olutoki MO, Olagunju AT, Adeyemi JD. Correlates of depressive illness among the elderly in a mixed urban community in Lagos, Nigeria. Aging Ment Health. 2014; 18(5): 561-9. [ Links ]

69. Bower KM, Thorpe RJ Jr, LaVeist TA. Perceived racial discrimination and mental health in low-income, urban-dwelling whites. Int J Health Serv. 2013; 43(2): 267-80. [ Links ]

70. Heilemann M, Frutos L, Lee K, Kury FS. Protective strength factors, resources, and risks in relation to depressive symptoms among childbearing women of Mexican descent. Health Care Women Int. 2004; 25(1): 88-106. [ Links ]

71. Moustgaard H, Joutsenniemi K, Martikainen P. Does hospital admission risk for depression vary across social groups? A population-based register study of 231,629 middle-aged Finns. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014; 49(1): 15-25. [ Links ]

72. Miranda J, Siddique J, Belin TR, Kohn-Wood LP. Depression prevalence in disadvantaged young black women African and Caribbean immigrants compared to US-born African Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005; 40(4): 253-8. [ Links ]

73. Cuellar I, Bastida E, Braccio SM. Residency in the United States, subjective well-being, and depression in an older Mexican-origin sample. J Aging Health. 2004; 16(4): 447-66. [ Links ]

74. Diwan S. Limited English proficiency, social network characteristics, and depressive symptoms among older immigrants. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008; 63(3): S184-91. [ Links ]

75. Batistoni SS, Neri AL, Cupertino AP. Prospective measures of depressive symptoms in community-dwelling elderly individuals. Rev Saúde Pública. 2010; 44(6): 1137-43. [ Links ]

76. Almeida OP, Pirkis J, Kerse N, Sim M, Flicker L, Snowdon J, et al. Socioeconomic disadvantage increases risk of prevalent and persistent depression in later life. J Affect Disord. 2012; 138(3): 322-331. [ Links ]

77. Dennis EF, Webb DA, Lorch SA, Mathew L, Bloch JR, Culhane JF. Subjective social status and maternal health in a low income urban population. Matern Child Health J. 2012; 16(4): 834-43. [ Links ]

78. Alley DE, Lloyd J, Pagán JA, Pollack CE, Shardell M, Cannuscio C. Mortgage delinquency and changes in access to health resources and depressive symptoms in a nationally representative cohort of Americans older than 50 years. Am J Public Health. 2011; 101(12): 2293-8. [ Links ]

79. McLaughlin KA, Nandi A, Keyes KM, Uddin M, Aiello AE, Galea S, et al. Home foreclosure and risk of psychiatric morbidity during the recent financial crisis. Psychol Med. 2012; 42(7): 1441-8. [ Links ]

80. O'Campo P, Eaton WW, Muntaner C. Labor market experience, work organization, gender inequalities and health status: results from a prospective analysis of US employed women. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 58(3): 585-94. [ Links ]

81. Liu RX, Chen Z-Y. The effects of marital conflict and marital disruption on depressive affect: a comparison between women in and out of poverty. Soc Sci Quarterly. 2006; 87(2): 250-71. [ Links ]

82. Chou KL. Perceived discrimination and depression among new migrants to Hong Kong: the moderating role of social support and neighbourhood collective efficacy. J Affect Disord. 2012; 138(1-2): 63-70. [ Links ]

83. English D, Lambert SF, Evans MK, Zonderman AB. Neighborhood racial composition, racial discrimination, and depressive symptoms in African Americans. Am J Community Psychol. 2014; 54(3-4): 219-28. [ Links ]

84. Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel BA, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among african american women in Detroit: results from a longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 2006; 96(7): 1265-70. [ Links ]

85. Melchior M, Chastang JF, Leclerc A, Ribet C, Rouillon F. Low socioeconomic position and depression persistence: longitudinal results from the GAZEL cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2010; 177(1-2): 92-6. [ Links ]

86. Skapinakis P, Weich S, Lewis G, Singleton N, Araya R. Socio-economic position and common mental disorders. Longitudinal study in the general population in the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 189: 109-17. [ Links ]

87. Eaton WW, Kalaydjian A, Scharfstein DO, Mezuk B, Ding Y. Prevalence and incidence of depressive disorder: the Baltimore ECA follow-up, 1981-2004. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007; 116(3): 182-8. [ Links ]

88. Garbarski D. Perceived social position and health: Is there a reciprocal relationship? Soc Sci Med. 2010; 70(5): 692-9. [ Links ]

89. Berchick ER, Gallo WT, Maralani V, Kasl SV. Inequality and the association between involuntary job loss and depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2012; 75(10): 1891-4. [ Links ]

90. Kim D. Blues from the neighborhood? Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiol Rev. 2008; 30: 101-17. [ Links ]

91. Wee LE, Yong YZ, Chng MW, Chew SH, Cheng L, Chua QH, et al. Individual and area-level socioeconomic status and their association with depression amongst community-dwelling elderly in Singapore. Aging Ment Health. 2014; 18(5): 628-41. [ Links ]

92. Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Creatore MI, Gozdyra P, Glazier RH. Urban neighborhoods, chronic stress, gender and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2006; 63(10): 2604-16. [ Links ]

93. Vallée J, Cadot E, Roustit C, Parizot I, Chauvin P. The role of daily mobility in mental health inequalities: the interactive influence of activity space and neighbourhood of residence on depression. Soc Sci Med. 2011; 73(8): 1133-44. [ Links ]

94. Van Praag L, Bracke P, Christiaens W, Levecque K, Pattyn E. Mental health in a gendered context: Gendered community effect on depression and problem drinking. Health Place. 2009; 15(4): 990-8. [ Links ]

95. Aneshensel CS, Wight RG, Miller-Martinez D, Botticello AL, Karlamangla AS, Seeman TE. Urban neighbourhoods and depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007; 62(1): S52-9. [ Links ]

96. Walters K, Breeze E, Wilkinson P, Price GM, Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher A. Local area deprivation and urban-rural differences in anxiety and depression among people older than 75 years in Britain. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94(10): 1768-74. [ Links ]

97. Mullings JA, McCaw-Binns AM, Archer C, Wilks R. Gender differences in the effects of urban neighborhood on depressive symptoms in Jamaica. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2013; 34(6): 385-92. [ Links ]

98. Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Traffic stress, vehicular burden and well-being: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 59(2): 405-14. [ Links ]

99. Berke EM, Gottlieb LM, Moudon AV, Larson EB. Protective association between neighborhood walkability and depression in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007; 55(4): 526-33. [ Links ]

100. Galea S, Ahern J, Rudenstine S, Wallace Z, Vlahov D. Urban built environment and depression: a multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005; 59(10): 822-27. [ Links ]

101. Messer LC, Maxson P, Miranda ML. The urban built environment and associations with women's psychosocial health. J Urban Health. 2013; 90(5): 857-71. [ Links ]

102. Li LW, Liu J, Zhang Z, Xu H. Late-life depression in Rural China: do village infrastructure and availability of community resources matter? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015; 30(7): 729-36. [ Links ]

103. Wilson-Genderson M, Pruchno R. Effects of neighborhood violence and perceptions of neighborhood safety on depressive symptoms of older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 85: 43-9. [ Links ]

104. Pikhartova J, Chandola T, Kubinova R, Bobak M, Nicholson A, Pikhart H. Neighbourhood socioeconomic indicators and depressive symptoms in the Czech Republic: a population based study. Int J Public Health. 2009; 54(4): 283-93. [ Links ]

105. Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Zenk SN, Parker EA, Lichtenstein R, Shellman-Weir S, et al. Psychosocial stress and social support as mediators of relationships between income, length of residence and depressive symptoms among African American women on Detroit's eastside. Soc Sci Med. 2006; 62(2): 510-22. [ Links ]

106. Fortney J, Rushton G, Wood S, Zhang L, Xu S, Dong F, et al. Community-level risk factors for depression hospitalizations. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007; 34(4): 343-52. [ Links ]

107. Lee MA. Neighborhood residential segregation and mental health: a multilevel analysis on Hispanic Americans in Chicago. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 68(11): 1975-84. [ Links ]

108. Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Osypuk TL, Rapp SR, Seeman T, Watson KE. Is neighborhood racial/ethnic composition associated with depressive symptoms? The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 71(3): 541-50. [ Links ]

109. Beard JR, Cerdá M, Blaney S, Ahern J, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhood characteristics and change in depressive symptoms among older residents of New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99(7): 1308-14. [ Links ]

110. Glymour MM, Mujahid M, Wu Q, White K, Tchetgen EJ. Neighborhood disadvantage and self-assessed health, disability, and depressive symptoms: longitudinal results from the health and retirement study. Ann Epidemiol. 2010; 20(11): 856-61. [ Links ]

111. Wight RG, Cummings JR, Karlamangla AS, Aneshensel CS. Urban neighborhood context and change in depressive symptoms in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009; 64(2): 247-51. [ Links ]

112. Cagney KA, Browning CR, Iveniuk J, English N. The onset of depression during the great recession: foreclosure and older adult mental health. Am J Public Health. 2014; 104(3): 498-505. [ Links ]

113. Cooper HL, Hunter-Jones J, Kelley ME, Karnes C, Haley DF, Ross Z, et al. The aftermath of public housing relocations: relationships between changes in local socioeconomic conditions and depressive symptoms in a cohort of adult relocaters. J Urban Health. 2014; 91(2): 223-41. [ Links ]

114. Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, Gardner KA. Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005; 114(1): 3-15. [ Links ]

115. Fernández-Niño JA, Manrique-Espinoza BS, Bojorquez-Chapela I, Salinas-Rodríguez A. Income inequality, socioeconomic deprivation and depressive symptoms among older adults in Mexico. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 24; 9(9): e108127. [ Links ]

116. Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard J, Vlahov D. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007; 17(3): 171-9. [ Links ]

117. Wight RG, Aneshensel CS, Barrett C, Ko M, Chodosh J, Karlamangla AS. Urban neighbourhood unemployment history and depressive symptoms over time among late middle age and older adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013; 67(2): 153-8. [ Links ]

118. Weich S, Twigg L, Lewis G. Rural/non-rural differences in rates of common mental disorders in Britain: prospective multilevel cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 188: 51-7. [ Links ]

119. Gariepy G, Blair A, Kestens Y, Schmitz N. Neighbourhood characteristics and 10-year risk of depression in Canadian adults with and without a chronic illness. Health Place. 2014; 30: 279-86. [ Links ]

120. Marshall A, Jivraj S, Nazroo J, Tampubolon G, Vanhoutte B. Does the level of wealth inequality within an area influence the prevalence of depression amongst older people? Health Place. 2014; 27: 194-204. [ Links ]

121. Echeverría S, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, Borrell LN, Jackson S. Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Health Place. 2008; 14(4): 853-65. [ Links ]

122. Tomita A, Burns JK. A multilevel analysis of association between neighborhood social capital and depression: evidence from the first South African National Income Dynamics Study. J Affect Disord. 2013; 144(1-2): 101-5. [ Links ]

123. Giraldez-Garcia C, Forjaz MJ, Prieto-Flores ME, Rojo-Perez F, Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Martinez-Martin P. Individual's perspective of local community environment and health indicators in older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013; 13(1): 130-8. [ Links ]

124. Quatrin LB, Galli R, Moriguchi EH, Gastal FL, Pattussi MP. Collective efficacy and depressive symptoms in Brazilian elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014 Nov-; 59(3): 624-9. [ Links ]

125. Fujiwara T, Kawachi I. Social capital and health. A study of adult twins in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2008; 35(2): 139-44. [ Links ]

126. Takagi D, Kondo K, Kondo N, Cable N, Ikeda K, Kawachi I. Social disorganization/social fragmentation and risk of depression among older people in Japan: multilevel investigation of indices of social distance. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 83: 81-9. [ Links ]

127. Gapen M, Cross D, Ortigo K, Graham A, Johnson E, Evces M, et al. Perceived neighborhood disorder, community cohesion, and PTSD symptoms among low-income African Americans in an urban health setting. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011; 81(1): 31-7. [ Links ]

128. King K, Ogle C. Negative life events vary by neighborhood and mediate the relation between neighborhood context and psychological well-being. PLoS One. 2014; 9(4): e93539. [ Links ]

129. Teychenne M, Ball K, and Salmon J. Educational inequalities in women's depressive symptoms: the mediating role of perceived neighbourhood characteristics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012; 9(12): 4241-53. [ Links ]

130. Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Shen M, Shea S, Seeman T, Echeverria S, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of neighborhood cohesion and stressors with depressive symptoms in the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2009; 19(1): 49-57. [ Links ]

131. Fujiwara T, Kawachi I. A prospective study of individual-level social capital and major depression in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008; 62(7): 627-33. [ Links ]

132. Clark C, Ryan L, Kawachi I, Canner MJ, Berkman L, Wright RJ. Witnessing community violence in residential neighborhoods: a mental health hazard for urban women. J Urban Health. 2008; 85(1): 22-38. [ Links ]

133. Murayama H, Nishi M, Matsuo E, Nofuji Y, Shimizu Y, Taniguchi Y, et al. Do bonding and bridging social capital affect self-rated health, depressive mood and cognitive decline in older Japanese? A prospective cohort study. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 98: 247-52. [ Links ]

134. Cheong KS, Choi MH, Cho BM, Yoon TH, Kim CH, Kim YM, et al. Suicide rate differences by sex, age, and urbanicity, and related regional factors in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012; 45(2): 70-7. [ Links ]

135. Rodrigues NC, Werneck GL. Age-period-cohort analysis of suicide rates in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1979-1998. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005; 40(3): 192-6. [ Links ]

136. Frisch M, Simonsen J. Marriage, cohabitation and mortality in Denmark: national cohort study of 6.5 million persons followed for up to three decades (1982-2011). Int J Epidemiol. 2013; 42(2): 559-78. [ Links ]

137. Kim MH, Jung-Choi K, Jun HJ, Kawachi I. Socioeconomic inequalities in suicidal ideation, parasuicides, and completed suicides in South Korea. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 70(8): 1254-61. [ Links ]

138. Lorant V, Kunst AE, Huisman M, Costa G, Mackenbach J; EU Working Group on Socio-Economic Inequalities in Health. Socio-economic inequalities in suicide: a European comparative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005; 187: 49-54. [ Links ]

139. Torresani S, Toffol E, Scocco P, Fanolla A. Suicide in elderly South Tyroleans in various residential settings at the time of death: a psychological autopsy study. Psychogeriatrics. 2014; 14(2): 101-9. [ Links ]

140. Chang SS, Sterne JA, Wheeler BW, Lu TH, Lin JJ, Gunnell D. Geography of suicide in Taiwan: spatial patterning and socioeconomic correlates. Health Place. 2011; 17(2): 641-50. [ Links ]

141. O'Reilly D, Rosato M, Connolly S, Cardwell C. Area factors and suicide: 5-year follow-up of the Northern Ireland population. Br J Psychiatry. 2008; 192(2): 106-11. [ Links ]

142. Kposowa AJ, McElvain JP, Breault KD. Immigration and suicide: the role of marital status, duration of residence, and social integration. Arch Suicide Res. 2008; 12(1): 82-92. [ Links ]

143. Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Cause-specific mortality differences across socioeconomic position of municipalities in Japan, 1973-1977 and 1993-1998: increased importance of injury and suicide in inequality for ages under 75. Int J Epidemiol. 2005; 34(1): 100-9. [ Links ]

144. Pearce J, Barnett R, Collings S, Jones I. Did geographical inequalities in suicide among men aged 15-44 in New Zealand increase during the period 1980-2001? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007; 41(4): 359-65. [ Links ]

145. Rezaeian M, Dunn G, St Leger S, Appleby L. Ecological association between suicide rates and indices of deprivation in the north west region of England: the importance of the size of the administrative unit. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60(11): 956-61. [ Links ]

146. Kunst AE, van Hooijdonk C, Droomers M, Mackenbach JP. Community social capital and suicide mortality in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional registry-based study. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: 969. [ Links ]

147. Van Hooijdonk C, Droomers M, Deerenberg IM, Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. The diversity in associations between community social capital and health per health outcome, population group and location studied. Int J Epidemiol. 2008; 37(6): 1384-92. [ Links ]

148. Sundquist K, Hamano T, Li X, Kawakami N, Shiwaku K, Sundquist J. Linking social capital and mortality in the elderly: a Swedish national cohort study. Exp Gerontol. 2014; 55: 29-36. [ Links ]

149. Qi X, Tong S, Hu W. Preliminary spatiotemporal analysis of the association between socio-environmental factors and suicide. Environ Health. 2009 1; 8: 46. [ Links ]

150. Miller JR, Piper TM, Ahern J, Tracy M, Tardiff KJ, Vlahov D, et al. Income inequality and risk of suicide in New York City neighborhoods: a multilevel case-control study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005; 35(4): 448-59. [ Links ]

151. Modrek S, Ahern J. Longitudinal relation of community-level income inequality and mortality in Costa Rica. Health Place. 2011; 17(6): 1249-57. [ Links ]

152. Blakely T, Atkinson J, Ivory V, Collings S, Wilton J, Howden-Chapman P. No association of neighbourhood volunteerism with mortality in New Zealand: a national multilevel cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2006; 35(4): 981-9. [ Links ]

153. Searles VB, Valley MA, Hedegaard H, Betz ME. Suicides in urban and rural counties in the United States, 2006-2008. Crisis. 2014; 35(1): 18-26. [ Links ]

154. Middleton N, Sterne JA, Gunnell D. The geography of despair among 15-44-year-old men in England and Wales: putting suicide on the map. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60(12): 1040-7. [ Links ]

155. Karlovi D, Gale R, Thaller V, Martinac M, Katini K, Matosi A. Epidemiological study of suicide in Croatia (1993-2003)-comparison of Mediterranean and continental areas. Coll Antropol. 2005; 29(2): 519-25. [ Links ]

156. Saraceno B. Mental health: scarce resources need new paradigms. World Psychiatry. 2004; 3(1): 3-5. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Manuela Silva

Chronic Diseases Research Center (CEDOC)

NOVA Medical School

Faculdade de Ciências Médicas

UNL, Campo dos Mártires da Pátria, 130

1169-056 Lisboa Portugal

Tel: +351 218 803 046

Fax: +351 218 803 079

E-mail: manuela.silva@gmail.com

Received: 20 February 2016

Revised: 11 June 2016

Accepted: 29 September 2016