The prevention of suicidal behavior in minors is an issue that remains unresolved. Considering, on the one hand, that suicidal behavior is among the leading causes of death among 15- to 19-year-olds worldwide (World Heatlh Organization [WHO], 2021a) and, on the other, that adolescence is an essential stage of human development during which the roots of later adulthood are put down, as well as the foundations of present and future society, ignoring this issue could be considered almost unconstitutional. Even more so, and based on the scientific literature, because suicide deaths can be prevented with timely, evidence-based, and often low-cost interventions (e.g., Mann et al., 2021; Phillips et al., 2014; Walsh et al., 2022; Zalsman et al., 2016). In this regard, we would like to recall the guiding principle of the Spanish Constitution: recognizing the right to health protection, as well as to organize and protect public health through preventive measures and the necessary benefits and services.

Suicidal behavior is part of human diversity. It is a complex, multifaceted, multidimensional, and multicausal phenomenon (Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021). It is a problem of life, where the person tries to find a solution to a situation experienced as a limit, an enormous difficulty that causes intolerable pain that he/she does not know how to or cannot solve in any other way (Al-Halabí & García Haro, 2021). Its delimitation, classification, etiology, treatment, and prevention is a difficult undertaking that does not have an easy solution. Suicidal behavior has not yet been well analyzed or understood, and it is a taboo subject plagued by myths and stigma. Even in the 21st century, many questions remain unanswered, perhaps the most pressing being the lack of a national plan for the prevention of suicidal behavior in Spain.

In this context the main objective of this narrative review is to make current information on suicidal behavior in the adolescent population available to psychology professionals and society as a whole. It is necessary to dismantle the unfounded beliefs associated with suicidal behavior, even among professionals (Al-Halabí et al., 2021b), as this allows to improve their vision, understanding, and approach. It should be made clear that talking about suicide as a public health problem helps to prevent it. Information, training, sensitization, and awareness of suicidal behavior, i.e., the knowledge of different professionals, family members, and the general population, is one of the best tools we have for its prevention. In this regard, it is worth highlighting Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030, which refers to "ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages", whose indicator 3.4 is the suicide mortality rate (Naciones Unidas [United Nations], 2018) which aims to reduce premature mortality from noncommunicable diseases by one-third through prevention and treatment, and to promote mental health and well-being.

The thread of this discussion will be as follows. First, a conceptual delimitation of suicidal behavior is made. Next, epidemiological issues are addressed. Thirdly, the most relevant psychological models are introduced. Fourth, risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in adolescents are discussed. Next, some of the existing measurement instruments in Spanish for the assessment of this population sector are presented. Subsequently, the main prevention models are discussed, focusing on the importance of educational environments. We also explain the empirically supported psychological treatments for the clinical approach to suicidal behavior in adolescents. Finally, to conclude, future research lines are discussed, and a brief recapitulation is made as a conclusion.

Due to limitations of space, we recommend that readers who are interested in delving deeper into the subject consult manuals on suicidal behavior (e.g., Anseán, 2014; Knapp, 2020; Miller, 2021; O’Connor & Pirkis, 2016; Wasserman, 2021) as well as different works in Spanish (e.g., Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021; Castellvi-Obiols & Piqueras, 2018; Espada et al., 2021; Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019; Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez de Albéniz, 2020; Pedreira-Massa, 2019) or guides (Grupo de Trabajo de revisión de la Guía de Práctica Clínica de prevención y tratamiento de la conducta suicida [Working Group for the revision of the Clinical Practice Guideline for the prevention and treatment of suicidal behavior], 2012, 2020).

Suicidal behavior: conceptual delimitation

Suicide, etymologically, refers to the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicidal behavior is a multifaceted concept that includes different expressions ranging from suicidal ideation (suicidal plan, thoughts of death, death wish, and suicidal ideation), through communication (suicidal threat, and verbal and nonverbal expression) and suicide plan, to the suicidal act (suicide itself, suicide attempt, attempt aborted by others, and self-injury) (Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez de Albéniz, 2020).

In this approach, suicidal behavior should not be understood as equivalent to death by suicide (or the misnamed “completed suicide”). The different phenotypic manifestations of suicidal behavior oscillate along a continuum of severity (well-being to death by suicide), where the level of risk for a particular person will be, theoretically, higher depending on whether he/she is close to the pole of suicide (Al-Halabí & García Haro, 2021). Although at the phenotypic level it may seem that the different expressions follow a linear trajectory in the manner of "stages of change", this does not mean that there can be non-linear or discontinuous changes over time. In this regard, the cusp catastrophe model can explain different processes such as the sudden onset of suicidal behavior without prior suicidal planning (Bryan et al., 2020). It should be remembered that human behavior does not conform well to that which is linear and unilateral.

Table 1 provides brief definitions of the different terms that are agglomerated within suicidal behavior (Turecki et al., 2019). However, far from there being a consensus on their nomenclature in the scientific literature, there is still a lack of a consensual conceptual definition and taxonomy, an aspect that impacts, among others, the understanding, assessment, prevention, and intervention of suicidal behavior (De Beurs et al., 2021; Goodfellow et al., 2018; Hill et al., 2020; Silverman, 2016; Silverman & Berman, 2014; Silverman & DeLeo, 2016; van Mens et al., 2020).

Table 1. Definitions of terms commonly used in suicidal behavior research (taken from Turecki et al, 2019).

| Concept | Delimitation |

|---|---|

| Suicide | Intentionally ending one's own life. |

| Suicidal behavior | Behaviors that may end one's life, whether fatal or not. This term excludes suicidal ideation. |

| Attempted suicide | Self-destructive and non-fatal behavior with inferred or actual intent to die. |

| Suicidal ideation | Any thought about ending one's own life. It can be active, with a clear plan to commit suicide, or passive, with thoughts about wanting to die. |

| Autolysis or self-destruction | Self-destructive behaviors with or without intent to die. Does not distinguish between attempted suicide and non-suicidal self-injury. |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | Self-injurious behaviors without intent to die. |

It is as important to define what is, as what is not the object of study. In this regard, the spectrum of suicidal behavior is neither defined nor classified as a mental disorder within the diagnostic manuals in use (International Classification of Diseases or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). Suicidal behavior can occur in the presence or absence of a diagnosis of mental disorder (e.g., depressive episode) (García-Haro et al., 2020) and, in turn, it is also transdiagnostic, i.e., it can be present in different health problems, both physical and psychological. Similarly, deliberate self-harm behavior (DSH) should not be confused with non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). However, as a brief note, it should be noted that non-suicidal self-injury is a major public health problem among adolescents (Arensman et al., 2018). While at the theoretical level the distinction between suicidal behaviors and self-injurious behaviors is clear (Kuehn et al., 2022), in the clinical reality of the adolescent population in particular, the categorical separation is more intricate and there is a high progression and overlap between self-injury and suicidal behaviors (Arensman et al., 2018; Brown & Plener, 2017; Gillies et al., 2018).

Epidemiology of suicidal behavior in adolescents

Epidemiological figures on suicidal behavior may vary according to different factors such as, for example, age, gender, educational level, or country.

Worldwide suicide mortality rates are estimated at 3.77/100000 people, whereas in Spain the figure is 1.47/100000 people (Glenn et al., 2020). In a meta-analysis (Lim et al., 2019), it was found that in adolescents the lifetime prevalence and 12-month prevalence of attempted suicide was 6% (95% confidence interval (CI): 4.7-7.7%) and 4.5% (95% CI: 3.4-5.9%), respectively. The lifetime prevalence and 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation was 18% (95% CI: 14.2-22.7%) and 14.2% (95% CI: 11.6-17.3%), respectively. In adolescent and young adult samples, females had a higher risk of suicide attempt (odds ratio 1.96; 95% CI 1.54-2.50), and males of suicide death (hazard ratio 2.50; 95% CI 1.8-3.6) (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019).

According to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE1) a total of 3,475 Spanish minors (from 5 to 19 years of age) died by suicide in the period 1980-2020. And 128,483 people (of all age ranges) have been registered as having died by suicide since this phenomenon has been recorded by the INE. Moreover, if for each death by suicide about 20 attempts are calculated, a total of 2,569,660 attempts are estimated during this period. These figures are devastating.

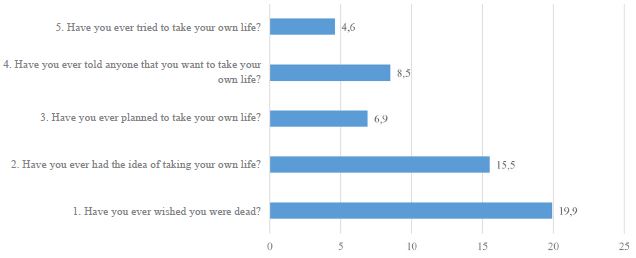

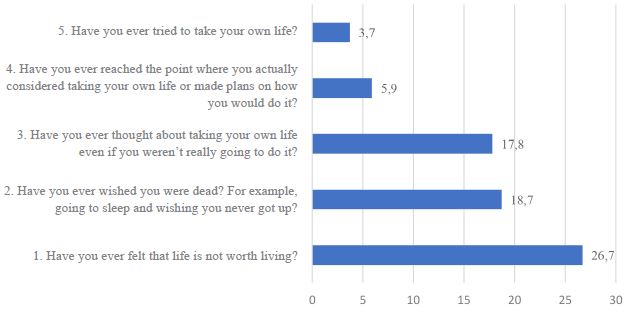

According to the INE (2021), 3,941 people committed suicide in 2020, of whom 300 were young people (14 to 29 years old). In Spain, the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation in the adolescent population is around 30%, while the prevalence of suicide attempts is approximately 4% (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2018; Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez de Albéniz, 2020). Figure 1 shows the prevalence of suicidal behavior, measured with the Paykel Suicidal Behavior Scale (Paykel et al., 1974) in a representative sample of the Spanish adolescent population. Figure 2 shows preliminary data on the prevalence of suicidal behavior, assessed with the SENTIA scale (Díez-Gómez et al., 2020), in a sample of 6,050 Spanish adolescents (3,224 females, age range 11-19 years) from the PSICE study (Psychology in Educational Contexts) coordinated by the Spanish Psychological Association and Psicofundación. Similarly, in this same study, when asked about suicidal behavior by means of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), adolescent version, the preliminary results indicate that 9.3% of the sample responded affirmatively to both the item "in the last month, has there been a time when you have seriously thought about ending your life?" and the item "at any time in your life, have you tried to kill yourself or commit suicide?"

Figure 1. Prevalence (%) of suicidal behavior in Spanish adolescents (from Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez de Albéniz, 2020).

Psychological models of suicidal behavior

Current theoretical models consider that suicidal behavior can be found in the complex dynamic interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors that are experienced by a given person according to a specific biography and socio-cultural circumstances.

It is a complex phenomenon, radically (at its root) psychological, rare (from a statistical point of view) in prevalence, multidetermined, dynamic (time-varying) and dependent on multiple parameters. From this approach, the epicenter of the equation would be the P for person, not the G for genetics or the B for brain. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the reasons-not the causes-why a person decides to commit suicide, since "no one attempts suicide without a reason".

There is no single cause why a person attempts to end his or her life. That is, there is no necessary and sufficient cause that determines such behavior. It is a probabilistic equation that comprises different parameters, which change from moment to moment, and among which the suffering and pain of the person is an essential factor. For the time being, the prognostic and predictive capacity of risk factors for suicidal behavior is very limited (Chiles et al., 2019; Franklin et al., 2017; Large et al., 2017; McHugh et al., 2019; Mulder et al., 2016; Runeson et al., 2017; Steeg et al., 2018).

Several models have been developed that attempt to explain suicidal behavior. Note that psychological models and theories of suicidal behavior provide a suitable context for organizing facts and concepts, confirming or refuting proposed predictions, as well as identifying and understanding the complex interplay of psychological variables linked to the development and maintenance of suicidal behavior. Currently, the most relevant models attempt to discriminate the factors that influence the development of suicidal ideation and those that cause the progression from ideation to attempt (Klonsky et al., 2018). Within these theories, the following have been integrated: a) the interpersonal theory of suicide (IPTS) (Joiner, 2005), which has demonstrated its particular usefulness in explaining suicidal behavior in the child and adolescent community and clinical population; b) the integrated motivational-volitional model (IMV) (O'Connor, 2011); c) the three-step theory (3ST) (Klonsky et al., 2021); and d) the fluid vulnerability theory (FVT) (Rudd, 2006). According to these models, in a cursory way, the focus should be on factors such as the following: (a) the perception of being a burden to oneself, one’s friends, or family; (b) frustrated belonging, that is, the experience of feeling lonely or disconnected from friendships, family, or other valued social circles; (c) entrapment or the perception of being blocked, feeling without escape, with no possibility of rescue, and powerless to change aspects of oneself; and (d) hopelessness (negative attributions about the future and the possibility of things changing).

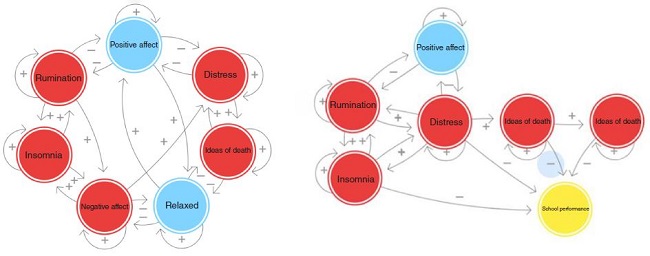

Others, such as the network model (Borsboom, 2017; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2022) or phenomenological or contextual models (García-Haro et al., 2018) can also be considered. The first conceives suicidal behavior as a complex dynamic system whose outcome is due to the complex interaction (or not) that is established over time between the different elements or variables that make up the network (see Figure 3). Secondly, from a contextual-existential point of view, suicidal crises and behaviors are understood as limit-solutions to situations of crisis, rupture, and existential entrapment of the self with the world, with others, and with oneself. The phenomenological core of suicide consists of a limit suffering experienced as "intolerable, inescapable, and interminable," for which the person sees no better solution than to put an end to a life that he/she does not consider acceptable (Al-Halabí & García Haro, 2021; Chiles et al., 2019). For the person who commits suicide, the goal is not death, it is to stop suffering.

Risk and protective factors in adolescent suicidal behavior

One of the classic approaches in the prevention of public health problems is the reduction of risk factors and the enhancement of protective factors. That is, reducing the variables associated with their increased occurrence and, at the same time, promoting the variables associated with their decrease. A risk factor does not necessarily have to be a good predictor, nor does it necessarily indicate causality. The modification of risk factors through interventions can affect the prevalence of suicidal behaviors. In this regard, according to Castellvi-Obiols and Piqueras (2018) recent meta-analytic review studies on risk factors for suicide indicate that according to the Population Attributable Risk (a measure that represents the amount of incidence that can be attributed to the risk factor in the general population), if an intervention that is 100% effective for suicidal ideation is carried out it could prevent 33% of total suicides in adolescents, a 100% effective intervention for school dropout could prevent 28% of total suicides (22% due to bullying), and a 100% effective intervention for mood disorders could prevent 26% of total suicides.

Risk and protective factors in suicidal behavior have been extensively studied in both adult (Franklin et al., 2017) and adolescent populations (Ati et al., 2021; Wasserman et al., 2021). In the review conducted by Ati et al. (2021), it was found that risk factors for suicidal behavior in adolescents can be grouped into two categories. On the one hand, there are the "internal" risk factors or those more linked to the person's routines and behavior, such as lack of problem-solving skills, ineffective coping with difficulties, abuse of time spent using smartphones, and health problems or unhealthy lifestyles (nutritional imbalance, menstrual problems, or altered sleep and rest patterns). On the other hand, "external" risk factors consist of family and social problems, such as a history of mental health problems and the presence of family conflict or other stressors, such as economic difficulties in families (unemployment situations, for example). For their part, social problems are linked to economic, labor, school (bullying, for example), and political factors. Both types are factors that can have a significant influence on suicidal behavior during adolescence. In the same review, protective factors for the prevention of suicidal behavior include the reformulation of a meaningful life (including spirituality), good health habits, and the quality of interactions between parents and children: good family communication, loving relationships, and adequate supervision of adolescents, allowing their development and autonomy while setting limits. Likewise, leisure activities such as the use of smartphones for "healthy" purposes (contacting friends, consulting information), reading books, and interest in movies are protective factors for suicidal behavior (Ati et al., 2021).

In another review, Castellvi-Obiols and Piqueras (2018) also highlight the role of affective disorders, suicide attempts, alcohol or substance abuse, and suicidal ideation as well-established predictors of new suicide attempts in the future. Likewise, different school adjustment problems (e.g., school dropout, truancy, bullying) are mentioned as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people (Wyman et al., 2019).

Assessment of suicidal behavior in adolescents

The assessment of suicidal behavior cannot be formulated in the vacuum of a clinical abstraction but must be linked to the actual contexts and practices where professionals provide help. The best tool for assessment is the clinical interview aimed at a comprehensive evaluation. In the assessment, it is important to identify both risk factors and protective factors, including the person's reasons for living. Scales or questionnaires can serve as a complement to the interview, although it is true that there is no psychometric instrument for assessing suicidal behavior that has a reliable predictive capacity. As we have previously pointed out, suicidal behavior is a plural and dynamic behavior, variable over time and highly dependent on contextual elements (including the professional relationship), making it very difficult to establish a reliable prediction in the future. Taking all this into account, within the framework of suicidal behavior, assessment and intervention are inseparable processes, with the moment of assessment being especially crucial so that the person, the adolescent in this case, feels that he/she is in a safe, trusting environment where he/she will not be judged, which will encourage the request for help. In fact, research shows that asking and talking to the person about the presence of suicidal thoughts decreases the risk of committing the act. Previous studies indicate that asking questions via appropriate tools about suicidal ideation does not cause suicidal thoughts or distress (Berman & Silverman, 2017). On the contrary, these approaches allow us to increase the probability of making a correct early detection in 600% of cases (Bryan et al., 2008). In general, it is recommended to avoid any kind of negative attitudes towards people with repeated suicidal behavior, favoring a professional care based on respect, humanity, and understanding towards these people.

In any case, and as a complement to the use of an empathic and comprehensive interview, an adequate assessment, prevention, and intervention of suicidal behavior requires the availability of measurement tools with adequate psychometric properties from which informed decisions can be made (e.g., screening of participants). Similarly, tests are important tools for understanding the phenomenon under study (e.g., classification, epidemiology, risk and protective factors), but also for testing the efficacy and usefulness of psychological interventions. In addition, most adolescents who attempt suicide communicate their thoughts before carrying it out, so their detection is literally a vital issue.

In previous literature, there is a wide range of measurement instruments for the assessment of suicidal behavior in adults and minors (Batterham et al., 2015; Runeson et al., 2017; Saab et al., 2021). The scale with the strongest scientific support (Interian et al., 2018) is the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (Posner et al., 2011) which has been validated in Spanish (Al-Halabí et al., 2016). Different measurement instruments have also been developed and validated in the adolescent population. Here we will only discuss those that have been validated in the Spanish population that have been duly validated in representative samples, namely the Paykel Suicide Scale (PSS) (Paykel et al., 1974) and the suicidal behavior in adolescents scale (SENTIA) (Díez-Gómez et al., 2020) and its brief version (Díez et al., 2021). The items of the PSS and the SENTIA-Brief are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2. Items of the SENTIA scale (brief version) for the assessment of suicidal behavior in adolescents (Díez et al., 2021).

| Item | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Have you ever wished you were dead? |

| 2 | Have you ever had the idea of taking your own life? |

| 3 | Have you ever planned to take your own life? |

| 4 | Have you ever told anyone that you want to take your own life? |

| 5 | Have you ever tried to take your own life? |

Note.Overall score "risk of suicidal behavior": sum of items with affirmative response.

Items referring to the "act/planning" subtype: items 5 and 3.

Items referring to the "communication" subtype: item 4.

Items referring to the subtype "ideation/hopelessness": items 1 and 2.

Table 3. Items of the Spanish version of the Paykel scale of suicidal behavior (Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez-Albéniz. 2020).

| Item | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Have you ever felt that life is not worth living? |

| 2 | Have you ever wished you were dead? For example, going to sleep and wishing you never got up? |

| 3 | Have you ever thought about taking your own life even if you weren't really going to do it? |

| 4 | Have you ever reached the point where you actually considered taking your own life or made plans on how you would do it? |

| 5 | Have you ever tried to take your own life? |

The PSS is a self-report instrument that assesses different expressions of suicidal behavior using five items with a dichotomous response format. The PSS scores have shown adequate psychometric properties in Spanish adolescents (Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez de Albéniz, 2020). The SENTIA scale is a self-report assessment of suicidal behavior with a dichotomous response format (yes/no). It consists of 16 items measuring a general factor of suicidal behavior and three specific factors (suicidal act/planning, communication, and ideation/hopelessness). The short version of SENTIA has been developed from the 16-item version and consists of a total of 5 items. Both versions of the SENTIA have shown adequate psychometric properties in Spanish adolescents (Díez-Gómez et al., 2020; Díez et al., 2021). PSS and SENTIA are brief, simple assessment tools with adequate metric quality that enable the assessment of suicidal behavior (ideation, planning, intention, communication, and behavior) in adolescence.

The aforementioned assessment tools can be used as a screening tool to make decisions such as psychological, educational, or early detection interventions in order to perform a more exhaustive psychological and comprehensive assessment. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of early identification and detection programs in suicidal behavior in young people using psychometric tools (Carli et al., 2021; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019). In this sense, one of the lines of action must be early detection by means of screening tests.

Prevention of suicidal behavior

Empirical evidence highlights that suicide is preventable. Effective intervention measures and resources are available for its prevention (p.ej., Mann et al., 2021; Riblet et al., 2017; Phillips et al., 2014; Zalsman et al., 2016). Obviously, for national or international responses to be effective, a comprehensive, multisectoral suicide prevention strategy is needed (Platt et al., 2019). In children and adolescents, restriction of access to lethal means, school-based skills and awareness training programs, and interventions delivered in clinical and community settings have proven effective in preventing suicidal behavior (Wasserman et al., 2021).

The WHO has developed the LIVE LIFE approach (WHO, 2021b) for suicide prevention where the following evidence-based interventions are recommended: (a) Limit access to the means of suicide (e.g., pesticides, firearms, certain medications); (b) Interact with the media for responsible reporting of suicide; (c) Foster socio-emotional life skills in adolescents; and (d) Early identify, assess, manage and follow up anyone who is affected by suicidal behaviors. This model can serve as a basis for developing a comprehensive national suicide prevention strategy.

A long list of strategies and programs designed for the prevention of suicidal behavior can be found in previous literature (Reifels et al., 2022). Prevention can be carried out based in the community, educational centers, health centers, etc. In general terms, and knowing that intervention strategies are heterogeneous, different forms of prevention have demonstrated their efficacy and usefulness (Mann et al., 2021; Riblet et al., 2017; Zalsman et al., 2016). However, there are areas such as work environments, universities, and primary care where there is still insufficient evidence. Models for suicide prevention in daily clinical practice can also be found in the literature, such as the AIM-SP (Assess, Intervene, Monitor for Suicide Prevention) model (Brodsky et al., 2018) (see Table 4).

Table 4. AIM-SP model for suicide prevention in everyday clinical practice (from Brodsky et al., 2018).

| AIM-SP | Steps and description |

|---|---|

| Evaluate | Explicitly ask about past and present suicidal ideation and behavior |

| Identify risk factors that are present | |

| Continued focus on the safety of the individual | |

| Intervene | Stanley and Brown Safety Plan (2012) |

| Develop coping strategies | |

| Integrate specific psychological treatments for suicide based on empirical evidence (CBT, DBT, or CAMS) | |

| Monitor | Increase the flexibility and availability of the clinician |

| Increase supervision during high-risk periods | |

| Involve family and other social support networks | |

| Solicit support from other clinicians and encourage case discussion |

Note: AIM-SP: Assess, Intervene, Monitor for Suicide Prevention; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; DBT: dialectical behavioral therapy; CAMS: Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality.

Preventing suicidal behavior in schools

Educational centers are the "natural" and ideal place to develop and implement actions for the promotion of emotional well-being and, specifically, for the prevention of suicidal behavior. Most adolescents spend long periods of time in the classroom, and schools are one of the main agents involved in socialization, as well as in training and promoting optimal development. Likewise, maintaining a safe and supportive school environment is an essential part of the overall mission of schools. In this respect, the Guidelines on School Health Services (WHO, 2021c) emphasizes that the school environment is an enabling environment for learning knowledge and for the acquisition of social-emotional competencies.

Programs for the prevention of suicidal behavior in schools can be grouped within universal or selective prevention (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019). The programs that, so far, have shown efficacy are: a) awareness and education via curriculum; b) peer leadership training; c) competency training; d) training of school staff; and e) screening of at-risk students. However, the scientific evidence for these programs is still limited, as there is a high heterogeneity of proposals and few randomized controlled trials that provide a high level of evidence and, therefore, recommend their use (Carli et al., 2021; Gijzen et al., 2022). The latest systematic reviews indicate that educational interventions, e.g. Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) and Signs of Suicide (SOS), are effective in preventing suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Carli et al., 2021). In this regard, the meta-analysis conducted by Gijzen et al. (2022) found that the effect size at posttest was small for both suicidal ideation (g = 0.15) and suicidal attempt (g = 0.30). Moreover, they seem to maintain their positive effects in the medium term (3-12 months) and do not cause harm (Pistone et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2018). In another meta-analysis by Walsh et al. (2022) interventions in educational settings, compared with controls, were associated with a 13% reduction in the likelihood of ideation (OR = 0.87, 95% CI [0.78, 0.96]) and a 34% reduction in the likelihood of attempts (OR = 0.66, 95% CI [0.47, 0.91]). In essence, these findings support suicide prevention in educational settings as a clinically relevant strategy.

Internationally, there are still few studies that have scientifically demonstrated that prevention programs are efficacious, efficient, and effective in schools, and this reality is even more urgent in Spain. In our context, the only known results are those of the multicenter SEYLE project (Wasserman et al., 2015) whose preventive interventions were carried out with adolescents in the Principality of Asturias (Wasserman et al., 2012).

Empirically supported psychological treatments for addressing suicidal behavior in adolescents

Professionals should use the intervention procedures that have empirical support based on the characteristics of the individuals, in this case minors, who seek help (Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021). In general terms, psychological treatments have been shown to be efficacious, effective, and efficient for addressing psychological disorders, as well as for different socioemotional adjustment difficulties that may occur during childhood and adolescence periods (e.g., Fonagy et al., 2015; Weisz & Kazdin, 2017).

In the field of suicidal behavior in adolescents there are different empirically supported psychological treatments (Al-Halabí et al., 2021a) (see Table 5). According to the levels of evidence and degrees of recommendation of the clinical practice guidelines of the Spanish National Health System (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2021), in the approach to suicidal behavior, dialectical-behavioral therapy for adolescents stands out as the only well-established psychological treatment with a grade A recommendation (Kothgassner et al., 2021). With a grade B recommendation are interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents, integrated CBT, mentalization-based therapy for adolescents, the Resourceful Adolescent Parent Program (RAP-P), integrated family intervention (Safe Alternatives for Teens & Youths), psychoeducation (Youth-Nominated Support Team), brief interventions (e.g., Teen Options for Change; As Safe As Possible), and Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention.

Table 5. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation for psychological interventions for suicidal behavior in childhood and adolescence (modified from Fonseca-Pedrero et al, 2021).

| Intervention | Level of evidence | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Dialectical behavioral therapy for adolescents | 1++ | A |

| Interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents | 1+ | B |

| Integrated cognitive behavioral therapy | 1+ | B |

| Mentalization-based therapy for adolescents | 1+ | B |

| Program for parents and adolescents | 1+ | B |

| Integrated family intervention | 1+ | B |

| Psychoeducation (Youth-nominated support) | 1+ | B |

| Teen Options for Change | 1+ | B |

| As Safe As Possible | 1+ | B |

| Family intervention for suicide prevention | 1+ | B |

The common components of effective interventions are as follows (Al-Halabí & García Haro, 2021): family approach, skills training (e.g., emotional regulation, stress tolerance, mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, and problem solving) and intensity and duration of treatment. In summary, psychotherapy seems to be the treatment of choice for minors who report different manifestations of suicidal behavior. In the words of Knapp (2020): "good psychotherapy saves lives".

Future prospects

Research on suicidal behavior is a complex subject that is in continuous progress. Here, and only by way of example, some of the most promising lines of progress in the study of suicidal behavior will be discussed, namely: a) developing and validating evidence-based psychological intervention programs; b) determining which components of the treatments are effective and for whom; c) providing practical guidelines for educators, family members, and health and social professionals, etc. d) disseminating accurate, scientific information, reducing the taboo and stigma associated with suicidal behavior; e) promoting access to psychological interventions for the general population and for specific subgroups (e.g., law enforcement agencies; ethnic minorities); f) developing and validating specific measurement instruments for suicidal behavior and related constructs; g) improving the study of protective factors, as well as mediating and moderating variables; h) incorporating new methodologies (e.g., outpatient assessment), procedures, and psychological models; h) promoting evidence-based prevention of suicidal behavior; i) developing joint policies, plans, and actions: coordination, cooperation, and co-responsibility; and j) training and coordinating with the media to report responsibly on suicide.

Recap

Suicidal behavior in adolescents is a public health problem both because of its prevalence and because of the associated personal, family, educational, and social-health consequences. Specifically, in the child and adolescent population, this phenomenon is relevant for several reasons, among which are that suicidal behaviors have increased in recent decades, more and more suicides are reported at younger ages, most people who have considered or attempted suicide did so for the first time during their youth, typically before the age of twenty, and it is associated with disability and disease burden (Asarnow & Ougrin, 2019; Cha et al., 2018; Glenn et al., 2020).

Suicidal behavior has a clear impact on both present and future society. Therefore, there is a need to address this societal challenge through research to enable informed decision making. However, the lack of resources at multiple levels is a real problem in light of the issues mentioned above. Needless to say, this situation requires action. Given the importance of the phenomenon under study for society as a whole, there is no other way but to continue working under the premise that suicidal behavior is preventable, and that individuals and families need psychology based on empirical evidence that enables the development of holistic, inclusive, multisectoral, personalized, accessible, and quality prevention systems.

In essence, suicide is preventable, it just needs prevention policies and programs. However, these have to be done (Platt et al., 2019). All these actions have to be framed within the need to implement a true national strategy for the promotion of mental health and emotional well-being, in general, and a national plan for suicide prevention, in particular, that improves the quality of life of present and future generations, always on the basis of cutting-edge research that allows informed decisions to be made for suicide prevention.

Remember that promoting, protecting, and caring for the mental health of the entire population, but particularly of the most vulnerable, is a constitutional duty. People deserve accessible, inclusive, public, and quality psychological care. We are all co-responsible and can play an important role in listening to and supporting our adolescents, helping them to build a good sense of belonging and a life worth living. It is time to act, generating hope through action.