Most of the information that psychologists obtain and handle in order to make any kind of decision comes from questionnaires. This statement can be considered transversal to the different areas of work in psychology, since the use of psychometric questionnaires can be considered universal (Muñiz et al., 2020). Although, obviously, the decision making is up to the psychology professional and not to the psychological test used, these decisions must be made based on quality information. It should always be kept in mind that any decision made affects the lives of the persons being assessed, and therefore cannot be taken lightly.

Although, as mentioned above, the quality of the test used is crucial for good decision making, it is not enough. The importance of all the parts involved in an assessment process should not be underestimated. For this reason, although this article deals in greater detail with the evaluation of the quality of the tests published in Spain, it is also intended to refer, albeit briefly, both to the psychology professional who performs the assessment and to the person being assessed.

The Psychology Professional

First of all, the training of psychology professionals must be broad, both in the different substantive aspects to be evaluated and in psychometrics (Muñiz et al., 2011). Just as in the development of a questionnaire, the first questions to be asked are: what do you want to measure, who do you want to evaluate, why do you want to measure (what for), and how are you going to perform the evaluations? Psychology professionals should ask themselves these same questions before conducting an assessment. The answers to these questions will guide them in selecting the appropriate questionnaire for their assessment objectives.

When faced with the question "what do we want to measure?" the psychologist is not faced with a simple answer. If the "jingle-jangle" fallacy is evident in any field of psychology, it is in this case. The "jingle fallacy" refers to the use of a single term to describe constructs that are different. The “jangle fallacy,” on the other hand, occurs when different terms are used to describe the same construct.

As is well known, there is no universal approach to constructs, i.e., when defining a construct, different theorists may select different behaviors to operationalize it. Logically, the selection of different behaviors leads to the fact that under the same label (e.g., depression) there are questionnaires that come from different theoretical frameworks, and that define the construct differently (jingle fallacy). Therefore, the psychologists must be able to select from all the questionnaires the ones that fit within the theoretical framework with which they are working. But at the same time, they must have sufficient substantive knowledge to determine that a questionnaire that assesses a construct named differently from the one they intend to measure can capture the behaviors they are interested in (jangle fallacy; Gonzalez et al., 2021).

In relation to "who do we want to evaluate?" the psychology professional should be aware of the possible differences between groups in the variable to be evaluated. In this way, the psychologist can select the questionnaire that best suits the characteristics of the people to be assessed. First of all, the selection of the reference group is of vital importance. Comparing a person's scores with scores of people who are not in his or her normative group leads, irremediably, to incorrectly assessing people. On the other hand, the psychologist must also know whether there are accommodations or whether the questionnaire has been developed following "universal design" recommendations. (AERA et al., 2014).

The answer to "why do you want to measure?" [i.e., what for] is also of vital importance. Multiple questionnaires assess a construct based on the same theoretical framework, but which have been created for different purposes. It should be borne in mind that the items that make up a questionnaire do not necessarily have to be the same when the purpose of a questionnaire is population screening or clinical evaluation. It should be remembered that tests are not or are no longer valid; statements about validity should refer to the interpretation of the scores for a given use (AERA et al., 2014). Therefore, determining the use to be made of the score and searching for questionnaires that have shown evidence of validity for that use is a central task of the psychologist.

To answer the question "how will the assessment be performed?" the psychologist must understand that there are multiple test application procedures (e.g., paper and pencil, computerized, adaptive, etc.) that can and should be adapted to the characteristics of the persons being assessed. The evaluation procedure should depend on the experience of the persons being assessed in answering questionnaires, experience with computers, etc. Not taking these conditioning factors into account can generate extraneous variables that affect the quality of the data obtained.

Although, so far, the emphasis is only being placed on the relationship between the psychologist and the questionnaire, there are other aspects that must be taken into account. Psychological professionals must know how to carry out the assessment correctly, establish an appropriate environment for the assessment, interpret the results obtained in the test properly, be able to transmit the information obtained in a clear, understandable, and useful way (this last point is often forgotten), and they are obliged to make an ethical use of the scores obtained.

Various associations have established different lines of work to improve the training of professionals. For the reader interested in the different proposals made, the work of Muñiz et al. (2020) is recommended.

The person being evaluated

Although psychology professionals cannot regulate the behaviors of those being assessed, they should be aware of the personal and legal responsibilities they acquire by being assessed (AERA et al., 2014). For example, the disclosure of material so that other assesses have prior information about the questionnaire to be used, as well as being a possible infringement of the copyright of the questionnaire, poses a severe threat to the validity of the inferences to be made from the result obtained in the assessment. Therefore, although it is not a direct responsibility of psychologists, a didactic task should be carried out to show the importance of responsible behavior in the assessment. The importance of the behavior of the person being assessed, and the threat to the validity of the inferences made, can be seen in the large number of scientific articles that aim to detect possible irregular behavior by assesses (e.g., Steger et al., 2021; Décieux, 2022; Ranger et al., 2022; Schultz et al., 2022).

The questionnaire

The assessment instruments used are expected to have certain characteristics that justify their use. For example, the psychometric properties must be good (the assessment must be carried out with adequate precision, the questionnaire must have shown evidence of validity, etc.), the norms must be up-to-date, and the sample used both for scoring and for the calculation of the psychometric properties must be adequate for the intended use.

All the information on the quality of the questionnaire must appear in the manual, and therefore, since it is provided by the publishing house responsible for the creation or adaptation of the test, it runs the risk of having a certain level of bias. For this reason, as occurs in other countries in our environment (e.g., the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, etc.), the Test Commission of the Spanish Psychological Association has designed a standardized review model that allows users to be aware of the technical quality of the questionnaires. This process involves both the test publishers (without whose help this process could not be developed), experts in the substantive subject of the test to be evaluated, experts in psychometrics, and, of course, the National Test Commission.

For those readers interested in reviews carried out in other countries, we recommend reading Evers (2012) or, for example, visiting the website of the Buros Center for Testing (http://www.buros.org) where evaluations of tests in Spanish can also be found.

This article presents the results obtained in the ninth national review of the tests published in Spain. In total, following this review, a total of 89 tests have been assessed since its inception in 2012. The results of the reviews carried out are public and are freely available on the website of the Spanish Psychological Association at the following web address: https://www.cop.es/index.php?page=evaluacion-tests-editados-en-espana. Likewise, on the same website, the readers can access each of the general reports made on how each of the annual reviews was carried out and the general conclusions that can be drawn (Elosua & Geisinger, 2016; Fonseca-Pedrero & Muñiz, 2017; Gómez-Sánchez, 2019; Hernández et al., 2015; Hidalgo & Hernández, 2019; Muñiz et al., 2011; Ponsoda & Hontangas, 2013; Viladrich et al., 2020).

Method

Participants

In order to carry out the evaluations of the different selected tests, 12 university professors were contacted to act as reviewers. The selection of these reviewers was carried out aiming to ensure gender equity, that the greatest number of Spanish universities were represented, and that the persons selected were experts in the construct evaluated or in psychometrics, and that there was no conflict of interest of any kind. Each test was evaluated by two reviewers, one an expert in the substantive subject and the other in psychometrics. Table 1 lists the reviewers who collaborated in the evaluation.

Table 1. List of reviewers participating in the ninth test review.

| Name and Surname | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Juana María Breton López | Jaume I University |

| Ramón Fernández Pulido | University of Salamanca |

| María José Fernández Serrano | University of Granada |

| Carmen García García | Universidad Autónoma de Madrid |

| Arantxa Gorostiaga Manterola | University of the Basque Country |

| Nicolás Gutiérrez Palma | University of Jaén |

| Francisco Pablo Holgado Tello | UNED |

| Francisco Javier del Rio Olvera | University of Cadiz |

| María Soledad Rodríguez González | University of Santiago de Compostela |

| Elena Rodríguez Naveiras | European University of the Canary Islands |

| Manuel Jesús Ruiz Muñoz | University of Extremadura |

| Inmaculada Valor-Segura | University of Granada |

Instrument

CET-R. The Cuestionario para la Evaluación de los Test Revisado [Questionnaire for Test Evaluation-Revised] (CET-R; Hernández et al., 2016) which is based on the Test Review Model developed by the European Federation of Professional Psychologists Associations (Evers et al., 2013).

The questionnaire is made up of three different sections preceded by brief instructions addressed to the reviewers, which provide information on the procedure to be followed to complete the different sections described below:

General description of the test. It is made up of 28 items in which the different characteristics of the evaluated questionnaire (e.g., date of publication, date of adaptation, area of application, format of the items, description of the populations to which the test is applicable, or the price of the complete set) are assessed in both closed and short answer format.

-

Assessment of the characteristics of the test. This section is further divided into:

General characteristics of the questionnaire (10 items). It evaluates aspects such as the quality of the test materials (objects, printed material, or software), the theoretical foundation, the quality of the test adaptation process, the quality of the item development process, among others. The response format is a 5-point graded scale (1: Inadequate, 2: Adequate with shortcomings, 3: Adequate, 4: Good, and 5: Excellent) in which some items include the options "Characteristic not applicable to this instrument" or "No information provided in the documentation."

-

Validity (19 items). This section evaluates different types of validity evidence of the questionnaire. The response format is the same as in the previous section. The items are distributed as follows:

▪ Evidence of validity based on test content (2 items assessing both the quality of the content representation and the expert judgment made).

▪ Evidence of validity in relation to other variables (14 items). This section evaluates the relationship (both convergent and discriminant) with different tests, as well as with an external criterion. In this section, as well as the 14 items mentioned above, 5 brief questions are included, in which the reviewer must indicate the procedure for obtaining the samples, the representativeness of the samples, etc.

▪ Evidence of validity based on internal structure (2 items in which both the quality of the study of the dimensional structure of the questionnaire and the quality of the study of the possible differential item functioning are evaluated).

▪ Accommodations made (1 item). In this section the response format is dichotomous (yes or no), and in affirmative cases a brief question must be answered in which the accommodations made and whether they have been adequately justified in the manual must be explained.

-

Reliability (14 items). This subsection begins with an item that asks about the information provided on the reliability of the test (types of coefficients, standard error of measurement, information function, etc.), and then goes on to evaluate reliability from different perspectives, both from the classical perspective and based on item response theory (IRT):

-

Scales and interpretation of scores (9 items). This section is further divided into:

At the end of each section (general characteristics, validity, reliability, and norms) there is an open question for the reviewers to express their general impressions in a more qualitative fashion. In this section they are asked to indicate the strengths they would highlight, as well as the deficiencies they have found that should be addressed.

Overall evaluation of the test. In this section, the reviewers asked to express in a maximum of one thousand words their opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of the test, recommendations on its use in the different professional areas, as well as the characteristics of the test that could be improved. Finally, a quantitative review of the characteristics evaluated is made by calculating the average of the scores given in the different items of the various sections.

The CET-R is freely available on the website of the Spanish Psychological Association (https://www.cop.es/index.php?page=evaluar-calidad).

Procedure

The different publishing houses (TEA-Hogrefe, Pearson Educación, GiuntiEOS, and CEPE) together with the National Test Commission decided on the different tests to be reviewed. In this ninth edition, 6 questionnaires were evaluated (see Table 2).

Table 2. List of tests evaluated in the ninth edition.

| Acronym | Name | Publishing House | Year of publication/revision |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAS | Escala de Ajuste Diádico [Dyadic Adjustment Scale] | TEA Hogrefe | 2017 |

| MacArthur | MacArthur Inventario de Desarrollo Comunicativo [MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory] | TEA Hogrefe | 2005 |

| Bayley | Escala Bayley de Desarrollo Infantil III [Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development - Third Edition] | Pearson Educación | 2015 |

| Raven's 2 | Matrices Progresivas de Raven 2 [Raven Progressive Matrices 2] | Pearson Educación | 2019 |

| CAG | Cuestionario de Autoconcepto Garley [Garley Self-Concept Questionnaire] | GiuntiEOS | 2019 |

| BECOLE-R | Batería de Evaluación Cognitiva de las Dificultades en Lectura y Escritura. Revisada y Renovada [Cognitive Assessment Battery for Reading and Writing Difficulties. Revised and Renewed] | CEPE | 2019 |

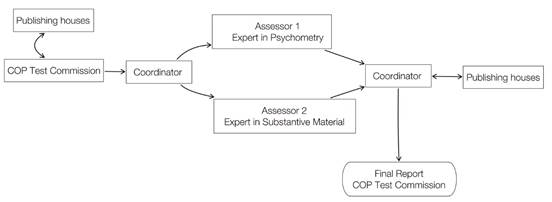

After deciding on the tests to be reviewed, the National Test Commission asked the review coordinator (the author of this article) to select the reviewers. After they accepted, they were sent both the electronic version of the CET-R and a complete copy of the questionnaire to be evaluated. The reviewers applied the CET-R to the test they had been assigned and, once completed, returned the completed CET-R to the coordinator. The reviewers' task was remunerated with 50 euros and with the questionnaire that they evaluated. Once the coordinator had the two reports completed by the reviewers, he pooled them and prepared a preliminary report for each of the tests. This report was sent to each publisher responsible for the questionnaire so for them to make the arguments they considered appropriate. After considering the arguments presented, the coordinator submitted the final reports to the National Test Commission.

A schematic summary of the procedure that was followed can be seen in the Figure 1.

Results

The final individual reports of the six tests evaluated in the ninth edition can be consulted and downloaded, together with those of the previous national reviews, on the web page of the Spanish Psychological Association (https://www.cop.es/index.php?page=evaluacion-tests-editados-en-espana).

Table 3 shows a summary of the average scores obtained by each of the questionnaires in each of the evaluated dimensions. These scores range from 1 (Inadequate) to 5 (Excellent).

In general terms, it should be noted that the great majority of the scores obtained were greater than 3.5, which is considered to be a step between the response alternatives Adequate (3) and Good (4), with the majority of the scores obtained being equal to or higher than 4 (Good). When comparing the scores obtained in the ninth edition with the history obtained from previous reviews, it can be seen that the results obtained follow the same trend as those obtained by the previously evaluated tests. As can be seen in Table 3, there are hardly any differences between the two scores.

Table 3. Scores obtained for the tests analyzed in the ninth review.

| DAS | CAG | BECOLE | BAYLEY-III | MacArthur | Raven's 2 | Average | History | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development: materials and documentation | 4.75 | 3 | 4.5 | 5 | 4.5 | 5 | 4.46 | 4.3 |

| Development: theoretical foundation | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4 | 4.5 | 3.92 | 4.1 |

| Development: adaptation | 5 | -- | -- | 3 | 4.5 | 5 | 4.38 | 4.3 |

| Development: item analysis | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 2 | -- | 3 | 3.70 | 3.8 |

| Validity: content | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4.5 | 4.25 | 3.96 | 3.8 |

| Validity: relationship with other variables | 4.5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4.25 | 3.63 | 3.6 |

| Validity: internal structure | -- | 4.5 | 4.5 | 3.5 | -- | -- | 4.17 | 3.7 |

| Validity: DIF analysis | -- | 4 | 4 | 2 | -- | -- | 3.33 | -- |

| Reliability: equivalence | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Reliability: internal consistency | 5 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4.58 | 4.2 |

| Reliability: stability | 4 | -- | -- | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3.5 |

| Reliability: IRT | -- | 4 | 4 | -- | -- | 4.5 | 4.17 | -- |

| Reliability: interrater | 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Scales and interpretation of scores | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 2.5 | 4 | 4.75 | 3.79 | 4.1 |

Note: The range of scores is between 1 and 5, with 1 = inadequate; 2 = Adequate with deficiencies; 2.5 and above = Adequate; 3.5 and above = Good; 4.5 and above = Excellent. The symbol -- indicates that no information is provided, or it is not applicable.

In the section evaluating the development of the questionnaire, we obtained averages that can be considered as good, approaching excellent (over four points and very close to 4.5) both in the quality of the materials and documentation of the questionnaires and in the process of cultural adaptation of the questionnaires. The average score in the other aspects evaluated in this component, theoretical foundation, and item analysis, was good, since although it was close to 4 points, it did not go above it.

In relation to the studies on the validity evidence of the questionnaires reviewed, it is noteworthy that all the questionnaires carried out studies on the evidence of validity, both in terms of content and in relation to other variables, obtaining a good average score. The score in the evidence of validity in relation to content stands out, since it is 3.96, far exceeding the cut-off point of 3.5 required to be considered good.

The differential item functioning (DIF) study also obtained a score that can be considered adequate. Among the different types of validity evidence, the study carried out on the internal structure of the questionnaires stands out, as it obtained a score that was close to that required to be considered excellent.

With respect to measurement accuracy, different approaches to reliability were reviewed. It should be noted that none of the questionnaires reviewed in this edition (or in any other) evaluates reliability from the perspective of equivalence by means of parallel forms. In the rest of the sections, reliability as internal consistency, as stability, and based on the framework of item response theory, the average scores obtained were excellent. The DAS is the only questionnaire that evaluates reliability following an interrater agreement procedure.

Finally, the average score obtained in the evaluation of the quality of the scales and the interpretations of the scores provided by the questionnaires was good. Within this section, it is noteworthy that the BAYLEY-III questionnaire obtained the lowest score with 2.5 points (lowering the total average of the tests analyzed in this review). This score is due to the fact that, despite the large sample size used by the test to make the scales, the origin of the participants was mostly American, which negatively penalizes the quality of the norms obtained.

Despite the fact that in the present review three questionnaires assess both DIF and reliability using an IRT procedure, there are no historical averages available with which to make a comparison in these sections. This is due to the fact that, although in previous editions some of the tests evaluated assessed these aspects, the amount of data obtained is still insufficient. Therefore, it is advisable that greater emphasis be placed on these aspects in the development and validity studies of published tests (Gómez-Sánchez, 2019; Muñiz & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019).

Conclusions

In general terms, it can be concluded that the results obtained in this review are similar to those obtained in previous ones. This, far from being a limitation or an indicator that the quality of the questionnaires published in Spain is not improving, reinforces the high quality of the tests evaluated so far, since the scores obtained in the different dimensions evaluated by the CET-R are systematically good or excellent. Likewise, it is also noteworthy that when the test evaluated is an adaptation, it has been carried out following the Guidelines of the International Test Commission, which in addition to improving the adaptations of the questionnaires also allows a better comparison of the scores between different cultures (Hernández et al., 2020; International Test Commission, 2018; Muñiz et al., 2013).

Although, as mentioned above, the overall rating of the questionnaires reviewed was good or excellent, it should be noted that the highest scores were obtained in the reliability section. Reliability is evaluated for all the tests as internal consistency (calculating both ( and (), although it is also evaluated as temporal stability (following the test-retest procedure) in four of the six tests, and half of the tests evaluate reliability following some procedure framed within IRT. None of the questionnaires considers reliability as equivalence, which is totally understandable if we consider the difficulty of creating two parallel tests in order to calculate it.

In relation to the validity dimension of the CET-R, it is noteworthy that all of the questionnaires reviewed examined the evidence of content validity and validity in relation to other variables. The highest score (4.17) was obtained in the evidence of validity in relation to internal structure (both in the exploratory and confirmatory versions). As an aspect to be improved in this section, it should be pointed out that there are hardly any studies in which the possible differential functioning of the items was evaluated (only three of the six questionnaires reviewed tested this).

The CET-R is a very useful tool when evaluating the quality of tests, although it is not exempt from problems that must be faced in order to try to obtain the best possible evaluations. One of the problems encountered is the fact that some items are too rigid to capture what they are intended to measure. For example, in items where the questionnaire was evaluated according to the size of the average correlations between the test and a criterion (i.e., item 2.11.2.2.2.6) a score of Excellent was obtained if the correlation was equal to or greater than 0.55. The value of the correlation is directly related to the dispersion of the sample, so if, for example, the sample is clinical and therefore very homogeneous, the correlation obtained will be low, implying that in this CET-R item the questionnaire will obtain a lower score than it really deserves. A possible solution to this problem is that in the same way that qualitative questions are used in the case of sample sizes, allowing the evaluator to justify the use of small sample sizes, these questions should be included in some CET-R items in order to produce a fairer evaluation of the questionnaires.

Another improvement that could be made to the CET-R is the fact that the evaluation made by the judges did not coincide. It should be taken into account that the evaluation is carried out both by a specialist in the subject that the test evaluates and by a specialist in psychometrics. Although this is a strong point, since it allows a view from both a substantive and psychometric perspective of the test to be evaluated, sometimes, as happens in any peer evaluation procedure, it leads to disagreements between the reviewers. This problem is not unique to the CET-R, as the levels of interrater agreement in evaluations of this type can be considered systematically low. (Hogan et al., 2021). It is therefore vitally important for the reviewer to try to resolve these differences, for example, by seeking a third reviewer or through a procedure of conciliation meetings between judges. Undoubtedly, any attempt to increase the levels of concordance between the test evaluators will further increase the validity of the conclusions drawn from the test scores.

The conduct of national assessments aims to improve the quality of the tests used, the use made of them, and with it, professional practice (Elosua & Geisinger, 2016). Without any doubt, it can be considered that the quality of the tests reviewed can be established as between good and excellent, which will lead to psychology professionals being able to make better assessments and thereby make better decisions. If the measurement of the psychological is the basis of the work of psychology professionals, having good measurement instruments is vital for the subsequent work to be coherent and well-founded.