Introduction

Is the mental health of our children and adolescents important? Is psychological well-being an essential pillar on which to base the health, education, and values of present and future society? Is it necessary to provide our children with the social-emotional competencies to face the vicissitudes of life? Are educational institutions the natural place where mental health should be promoted? In other words, if children and adolescents are our main capital as a society, is it constitutional to allow mental health problems and suicidal behavior to constitute the main causes of disability, disease burden, and death in our country? What is the cost of inaction? And in light of this scenario, what do we do? Ignore it or take action: what is our choice? You can reflect on each of the questions posed if you wish. Nevertheless, and as we will see throughout this article, it seems that we can conclude one thing: we are late.

Let us begin at the beginning. The thesis defended here is based on the simple idea that people deserve accessible, inclusive, public, and quality psychological care. According to the legal system established by the Spanish Constitution, it is necessary to "recognize the right to health protection, as well as to organize and protect public health through preventive measures and the necessary provisions and services". Without wishing to resort to the cliché, we cannot fail to affirm that "without mental health, there is no health". In this regard, it is also worth mentioning Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals (Naciones Unidas [United Nations], 2018), namely, "to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages". In particular, Target 3.4 has the aim to "reduce by 2030 premature mortality from non-communicable diseases by one-third through prevention and treatment, and promote mental health and well-being". There is no doubt that much progress has been made in mental health in recent decades. The level of understanding of human behavior and access to psychological treatment, among other things, have improved, as have the associated stigma and taboo. However, if we look at it from a different perspective, the response to this reality is quite different, as advances in leadership, governance, and funding for mental health are still conspicuous by their absence (World Health Organization, WHO, 2023).

Our goal is clear: to promote, protect, and care for the mental health of the entire population. And, in particular, of one of the most vulnerable groups: minors. The promotion of well-being and the prevention of psychological problems is the best investment for governments, regions, and institutions (WHO, 2021a). Not only for public health, but also for economic and social development. Investing in the mental health of the people who make up society is always the winning choice. Even knowing that this issue should not be the subject of debate, Table 1 shows some arguments in favor, as well as possible obstacles to increasing the necessary investment in mental health (WHO, 2013). To quote Benjamin Franklin, let us remember that "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure". And let us not forget that what you give to children, children will give to society.

Table 1. Arguments in Favor of and Potential Barriers to Investment in Mental Health (WHO, 2013).

| Perspective | Arguments for greater investment in public mental health | Potential obstacles to increased investment in public mental health |

|---|---|---|

| Public health | Mental disorders are a major cause of the global burden of disease; effective strategies exist to reduce this burden. | Mental disorders are not a major cause of mortality in the populations. |

| Economic well-being | Mental and physical health are basic elements of individual well-being. | Other components of well-being are also important (e.g., income, consumption). |

| Economic growth and productivity | Mental disorders reduce labor productivity and economic growth. | The impact of mental disorders on economic growth is not well understood (and is often assumed to be negligible). |

| Equity | Access to health is a human right; discrimination, neglect, and abuse are human rights violations. | People with a wide range of health challenges currently lack access to adequate health care. |

| Socio-cultural influence | Social support and solidarity are fundamental characteristics of societies. | Negative perceptions and attitudes about mental disorders (stigma). |

| Political influence | Government policies must address market failures and health priorities. | Low expressed demand for better services. |

Within this framework, the aim of this paper is to underscore, in the light of the epidemiological findings of the PSICE project (Psicología Basada en la Evidencia en Contextos Educativos [Evidence-Based Psychology in Educational Contexts]) (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2023), the importance of addressing mental health in educational contexts. There is an urgent need to implement programs both to promote psychological well-being for the entire educational community and to prevent mental health problems and difficulties in emotional and behavioral adjustment through the incorporation of psychology professionals in educational institutions. We start from the premise that the resources available in the public administration to meet this demand are scarce. In addition to the lack of personnel, two essential ingredients of prevention are systematically forgotten: early detection and early intervention. It is also urgent for the educational system to become aware of its responsibility in this field and to promote the development and consolidation of educational psychology professionals in educational institutions. Therefore, a perspective that understands the need for a specific psychological approach from promotion to intervention is mandatory and one that includes psychology practitioners who are members of a professional association, guaranteeing the competencies required by law.

The main outline will be as follows. First, an introduction to the study of human behavior and psychological adjustment problems is given and epidemiological findings are discussed. Secondly, the importance of educational institutions as the natural place to promote the psychological well-being and mental health of children is reasoned. Thirdly, the prevalence results derived from the PSICE study are mentioned. The paper ends with a summary section. It is not intended to be an exhaustive review of each and every one of the topics addressed, so we refer the reader to previous work (Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2023; Fernández-Hermida & Villamarín-Fernández, 2021; Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia [United Nations Children's Fund], 2022; Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021a; Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021b; Patel et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2021; WHO, 2021a).

Mental Health: When Nothing Psychological is Alien to us

Mental health is much more than the absence of disease. Psychology has as its cornerstone the study, understanding, and approach to people's behavior and openly recognizes its multi-causal, multidimensional, dynamic, plural, interactive, contextual, and functional nature. It is well known that human behavior is poorly-adapted to the linear, static, and unilateral models. Unicausal models (see, for example, neurotransmitter X causes disorder Z) cannot capture the enormous complexity inherent in human behavior. Likewise, psychological problems should be considered interactive entities, rather than fixed, natural illnesses (Pérez-Alvarez, 2021). The material cause of psychological problems would be the "problems of living" (see also adversities, burdens, threats, conflicts, crises, disappointments, frustrations, uncertainties, traumas, etc.) (Pérez-Álvarez, 2020) and not supposed intrapsychic or mental "breakdowns". It is considered essential to rescue a radically psychological vision of mental health problems, placing the "roots" of behavior in the intersubjective, interpersonal, and socio-cultural context. It would be obvious to argue that social determinants (and the school environment, therefore) have an impact on the mental health of individuals and on the use of social and health services (Verhoog et al., 2022). Also, human behavior is driven by reasons rather than causes, and these reasons need to be understood in the biographical context of the individual. Menninger (1927) explained this idea superbly, using the metaphor of the fish caught on the hook in order to describe the behavior of people who have unusual difficulties:

"When a trout rising in flight gets caught on the hook and finds itself unable to swim freely, it begins to struggle and splash, and it sometimes escapes.... In the same way, the human being struggles... with the hooks that trap him. Sometimes he masters his difficulties; sometimes they are too much for him. The struggles are all the world sees, and they usually misunderstand them. It is hard for a free fish to understand what is happening to one that is caught" (p. 3).

As the reader will discern, the contextual approach is defended here as the most genuine approach in psychology and the one most in line with the nature of psychological problems (Pérez-Álvarez & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021). In this sense, the reader is invited to reflect on the place of the "social" in the well-worn, but sometimes not so well understood, biopsychosocial model. A model is also defended here that places the person and his or her biography, capacities, and strengths (and not so much disabilities) at the center of the equation, where rather than speaking of the no ones, the nobodies, or the neglected, to paraphrase Galeano, we talk about specific people, with faces, names, and surnames. A truly inclusive perspective that includes and understands diversity as a value.

Mental health problems and psychological adjustment difficulties are among the major challenges facing educational, family, health, and social systems. Psychological problems are among the leading causes of associated disability and disease burden globally among young people (e.g., Gore et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2015). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) in its "World Mental Health Report: Transforming mental health for all” notes that one billion people worldwide have been diagnosed with a mental disorder (more than one in eight adults and adolescents). The largest groups are depression, with 280 million people, and anxiety, with 301 million. Neurodevelopmental disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar, and conduct disorders, to name a few, also affect hundreds of thousands of people worldwide. And let’s not forget, not for a second, deaths by suicide. The burden of disease associated with these problems is enormous. Mental disorders are also the leading cause of "years lived with disability" (YLD). One in six YLD can be attributed to a mental disorder. In addition, the actual burden of disease associated with these clinical syndromes is considerably higher due to the marked premature mortality of this group. The result: millions of people worldwide suffer for this reason without receiving the necessary care.

The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019 (Ferrari, 2022) is a collaborative working paper in which the prevalence and burden of disease estimates are made for 12 diagnoses of mental disorders by gender, across 23 age groups and 204 countries over the time interval between 1990 and 2019. The GBD 2019 revealed that mental disorders remained among the top ten causes of disease burden worldwide, with no evidence of an overall reduction in burden since 1990. Economically, the annual loss of human capital due to mental health disorders in the 0-19 age group is $387.2 billion, of which $340.2 billion is related to anxiety disorders and depressive disorders (Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia [United Nations Children's Fund], 2022).

The lifetime prevalence of presenting emotional and behavioral problems in the child and adolescent population is 13.4% (95% confidence interval, CI, 11.3-15.9%) (Polanczyk et al., 2015). The study by Barican et al. (2022) found that the overall prevalence of any child and adolescent mental disorder (aged 4-18 years), for developed countries, was 12.7% (95% CI, 10.1-15.9%). In our country, the Encuesta Nacional de Salud de España 2011/2012 [National Health Survey Spain 2011/2012] found that 4% of minors presented some emotional or behavioral problem (Basterra, 2016). This same survey, carried out with the informant-report version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997) in 2017, found that 13.2% of minors aged 4-14 years presented mental health risk. Other studies indicate that the estimated prevalence for any anxiety disorder in Spanish adolescents is 11.8%, while for any depressive disorder it is 3.4% (depressive symptoms were rated at 12%) (Canals et al., 2019).

In addition to the epidemiological findings mentioned above, in our country, suicide is the leading cause of unnatural death, even above traffic accidents (Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2023; Fonseca Pedrero et al., 2022). The latest data from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística [Spanish National Institute of Statistics, INE in Spanish], published in February 2023, (https://www.ine.es) indicate that 4,003 people died by suicide in 2021 (age-adjusted rate of 8.45 people per 100,000 inhabitants). In other words: 11 people died by suicide per day in Spain in 2021. This represents an increase of 4.4% compared to 2019. According to the Observatorio del Suicidio en España [Observatory of Suicide in Spain] (https://www.fsme.es/observatorio-del-suicidio-2021/), it is worth noting these data of interest:

There was a record number of deaths by suicide in children under 15 years of age, with a total of 22 people in 2021;

Death by suicide among children under 15 years of age has doubled compared to 2019 (7 in 2019 vs. 14 in 2020); and

Between 15 and 29 years of age, death by suicide is the leading absolute cause of death, with a total of 316 deaths per year, compared to 299 for traffic accidents and 295 for tumors.

According to the INE, a total of 3,475 Spanish minors (aged 5 to 19 years) have died by suicide in the period 1980-2021. And 132,486 people (of all age ranges) have been registered as having died by suicide since this phenomenon has been recorded by the INE. Moreover, if for each suicide death about 20 suicide attempts are calculated, a total of 2,649,720 attempts would be estimated for this time period. Furthermore, the data available to us are underestimated and, therefore, do not reflect the real dimension of this problem. The figures are devastating and call for reflection.

Age of onset, severity, persistence, and comorbidity are factors to consider in the study of psychological problems in childhood and adolescence (Fusar-Poli, 2019). Most diagnoses of mental disorders are received uninterrupted during the first 25 years of life. For example, difficulties in emotional or behavioral adjustment usually begin, in approximately 50% of cases, before the age of 15 years, and in 75% before the age of 25 years (Fusar-Poli, 2019). Furthermore, the development of the first mental disorder appears to occur before the age of 14 years in one third of cases and before the age of 18 years in almost half (48.4%). A recent meta-analysis has found that the peak age of developmental onset for any mental disorder is 14.5 years (Solmi et al., 2022). The overused division between disorders that occur in childhood and others that appear in adulthood is therefore meaningless. Similarly, experiencing mental health problems before the age of 14 years has been associated with an elevated risk of presenting mental disorders in adulthood (Mulraney et al., 2021). This risk is not so much associated with clinical diagnosis in adolescence, but rather with the intensity of symptomatology or distress.

The impact is not only limited to the rates of problems with clinical significance in terms of diagnosis, but also to those phenomena that do not reach the clinical threshold, that is, subclinical or subthreshold symptoms or even other difficulties or behaviors that are not included in the official taxonomies but are relevant, such as bullying or suicidal behavior (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2022). Note, also, that many of the risk factors that underlie mental health problems occurring in childhood and adolescence are modifiable (e.g., adverse experiences) (Dragioti et al., 2022) and are transdiagnostic in nature (Krueger & Eaton, 2015; Lynch et al., 2021). In this regard, the review conducted by Lynch et al. (2021) found several transdiagnostic risk factors for psychopathology in youth: deficits in executive functioning, stressful life events, maternal depression, high neuroticism, negative affectivity and behavioral inhibition, and low self-regulation. These findings have important implications for prevention and intervention and are related to the implementation of social and emotional learning (SEL) programs in educational settings (Durlak et al., 2022). Thus, improving emotion regulation or self-regulation, as well as reducing the environmental conditions that promote stressful life events may be particularly important objectives for prevention and intervention in psychological problems. Therefore, everything points to the fact that risk factors seem to be modifiable and common to many problems (González-Roz et al., 2023). Moreover, they may be modifiable within the school context.

The consequences of poor psychological adjustment impact other spheres of young people's lives (e.g., personal, family, school, social, economic, health) in the short, medium, and long term (Arrondo et al., 2022; Veldman et al., 2015). Worthy of note is that only about one in three adolescents with some type of emotional problem had sought professional help (Wang et al., 2005). Moreover, a delay in the early identification and detection of adolescents with possible difficulties in emotional or behavioral adjustment is often associated, among other aspects, with greater psychopathological symptomatology in adulthood, as well as with a worse short-, medium-, and long-term evolution or prognosis (e.g., greater number of relapses or hospitalizations) (Drancourt et al., 2013). These results point to the need for early detection and early intervention in order to prevent possible problems in psychological and school adjustment.

It is not only lack of resources that limits access to empirically supported treatments. Stigma (including self-stigma) is another major barrier that limits progress. People with mental disorders are often assumed to be lazy, weak, unintelligent, difficult, and sometimes violent and dangerous (Cuijpers et al., 2023). In this regard, information, training, sensitization, and awareness-raising in mental health, i.e., the literacy of different professionals, family members, and the general population is one of the best tools we have for prevention. Disseminating truthful, scientific information, reducing the taboo and stigma is a universal prevention measure (Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021). It is impossible to prevent something that cannot be talked about.

Making Every School a Mental Health-Promoting School: Services to Promote Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Schools

No educational system is effective if it does not promote the health and well-being of its educational community. The educational institution (e.g., primary school, high school) is undoubtedly the driving force behind the promotion of health and psychological well-being that enables care for vulnerable children and adolescents, within a truly equitable and inclusive system. UNESCO's Delors Report encapsulated this perfectly, in its title Learning: The Treasure Within (Delors, 1996).

Educational institutions are the "natural" and ideal place to develop and implement actions for the promotion of psychological well-being and, in particular, for the prevention of psychological adjustment difficulties and suicidal behavior (e.g., Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2023; Durlak et al., 2022; Lucas-Molina & Giménez-Dasí, 2019; WHO, 2021b). Most children and adolescents spend extended periods of time in the classroom, with educational institutions being one of the main agents involved in socialization, as well as in the formation and promotion of optimal development and learning. The educational institution, therefore, is the ideal context for prevention since, after the family environment, it is the place where children interact the most, creating significant experiences that help them build their identity, establish interpersonal relationships, and develop social-emotional competencies such as self-regulation, assertiveness, and resilience.

Similarly, maintaining a safe, inclusive, and supportive school environment is a central part of the overall mission of schools. In this regard, the Guidelines on School Health Services (WHO, 2021b) stresses that schools are essential for the acquisition of knowledge, social-emotional competencies, as well as the critical thinking skills necessary for a healthy future. In this regard, emotional education programs appear to improve social-emotional skills and attitudes, prosocial behavior, and academic performance, as well as reduce conduct problems, emotional distress, and drug use (Durlak et al., 2022). In turn, good health is linked to lower school dropout rates and higher academic achievement, as well as higher level of education and employment. In addition, several studies (Datu & King, 2018) evidence reciprocal effects between academic performance and psychological well-being, such that greater well-being predicts better academic performance and vice versa. In this sense, valuing the importance of natural environments for prevention and intervention in mental health in childhood and adolescence, educational institutions have become one of the most important contexts for the promotion of health and preventive interventions (Lucas-Molina & Giménez-Dasí, 2019; National Association of School Psychologists [NASP], 2021).

In relation to the above, an additional argument that justifies educational institutions as ideal places to implement actions with empirical support for the promotion of emotional well-being is that the variables that support it are not limited to the individual or personal level. Although the individual level is key, research shows that other equally relevant levels are included in the "well-being equation". For example, the ecological approach (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Simões et al., 2021) has served as a framework for understanding phenomena that occur in the educational context, such as bullying (Salmivalli et al., 2021; Swearer & Hymel, 2015) and as a basis for the development of interventions related to the prevention of difficulties such as, for example, suicidal behavior (Valido et al., 2023; Wyman et al., 2010). In this same sense, the contextual approach advocated above (Pérez-Álvarez & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021) is supported by empirical evidence on the potential of certain variables in the school environment to increase difficulties (e.g., attitudes towards violence, stigma related to mental health difficulties, low level of peer involvement in bullying situations) or to attenuate them (e.g., sense of belonging to the school, school climate, presence of teacher or student support). In conclusion, the context ceases to be simply a place and becomes an active agent whose dynamics have a direct impact on psychological well-being and, therefore, on its promotion.

It is worth mentioning here one of the maxims of the WHO and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization report: "making every school a health-promoting school" (World Health Organization & United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2021a). There is no doubt that this is a necessary commitment, in line with the times we live in. If extended to the field of mental health, these services in schools can, in coordination with other external services, improve access to care, enable early identification and treatment of possible mental health difficulties or problems, as well as possible neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., specific learning disorders, ADHD), reduce school absenteeism, and optimize student development and learning (Hess et al., 2017; Panchal et al., 2023). Mental health services in educational settings can also reduce barriers to access for the most vulnerable populations, including, but not limited to, minors from low-income households or at risk of exclusion (Kern et al., 2017; NASP, 2021). The WHO & UNESCO (2021b) in the Guidelines on School Health Services makes a recommendation on the need to implement comprehensive health services in schools. It provides a compendium of 87 specific interventions categorized as essential or appropriate for inclusion within school health services, either in all parts of the world or only in certain geographic contexts.

This approach, which holds that schools are the most important settings for health promotion, is not new. Nor should it come as a surprise to anyone. Health promotion and health education have a long empirically supported history. In fact, some autonomous communities in Spain have already developed actions in this direction (e.g., in the Valencian Community1). Talking about educational institutions directly affects minors. Childhood and adolescence are sensitive periods in human development. It is in these stages of the life cycle that the roots of future adult development are laid. The WHO, along with other organizations, has long recognized the link between health and education, as well as the potential for schools to play a central role in safeguarding the health and well-being of the educational community, especially students. As early as 1995, the WHO spoke of the six pillars of health-promoting schools:

Healthy school policies.

Physical school environment.

Social school environment.

Health skills and education.

Links with parents and the community.

Access to (school) health services.

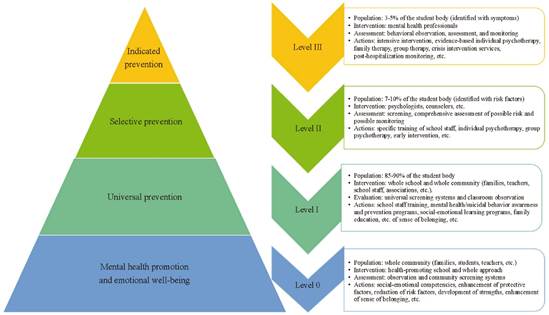

Figure 1 shows the eight essential guidelines for creating a sustainable health-promoting school system. It should also be noted that for these guidelines to be successful, and in line with the ecological perspective discussed above, they should be framed within a model of comprehensive action both in the educational institution ("whole-school approach"), and in society and community (Simões et al., 2021). This type of approach covers all aspects of the school experience, from school policies and culture to classroom practice. From this perspective, the prevention of psychological adjustment problems is a matter for the entire educational community, so it must involve all staff, students, management, and families, and it must ensure that everyone is aware of and supports the school's prevention strategies and approach. It is worth mentioning the multilayer or multilevel model that aims to implement different types of actions depending on the objectives and groups of action. Figure 2 shows a multilevel model that presents the different actions, ranging from the promotion of well-being to indicated prevention. It is an approach that facilitates personalized and phased care that focuses, firstly, on the promotion of well-being and, secondly, on prevention, either through early detection or intervention at the appropriate time within the educational institution and, finally, in case of persistence or severity of the problem, referral to external centers. This approach is in line with the response to intervention (RTI) model in educational contexts (Jimerson et al., 2016) which has been implemented in some institutions in our country for the prevention of specific learning difficulties (Jiménez, 2019). In addition, it is perfectly integrated into the proposal of the multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) aimed at the prevention of academic, behavioral, and emotional difficulties of students through the provision in schools of equitable and empirically based academic and psychological services through an ecological approach (Loftus-Rattan et al., 2023). The rationale for these multilevel models is in line with Rose's theorem (1994) according to which a large number of people at low risk may give rise to more cases of an "illness" than the small number at high risk. Consequently, priority should be given to universal and selective prevention, i.e., on the population as a whole, in this case, students.

Figure 1. Overview of the Standards for Being a "Health Promoting School (HPS)" (Taken from WHO & UNESCO, 2021b).

Figure 2. Multilevel Model for the Promotion of Emotional Well-Being and Prevention of Psychological Problems in Educational Contexts (Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2023).

In relation to the above, the National Association of School Psychologists of the United States promotes comprehensive school mental health services with the following arguments (NASP, 2021):

Students with good mental health are more successful in school and in life.

There is a growing and unmet need for mental health services for children, adolescents, and youth.

Schools are an ideal place to offer mental health services to children and adolescents.

Comprehensive school mental health services support the mission and purpose of schools: learning.

Comprehensive school-based mental health services are essential for creating and maintaining safe school environments.

Providing a continuum of school mental health services is fundamental in order to effectively address the full spectrum of student needs.

Educational psychologists provide services that relate mental health, behavior, and learning to school and home, as well as school and community services.

Educational psychologists are part of a team of professionals who provide these services in schools.

Do we have scientific evidence on whether psychological interventions prevent mental health problems? The answer is yes (e.g., Salazar de Pablo et al., 2020). Do we have empirically supported psychological interventions for addressing psychological problems in childhood and adolescence? The answer is also affirmative (e.g., Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2021; Weisz & Kazdin, 2017). Over the past decade, a number of psychological interventions to promote mental health and prevent mental health problems in schools have been trialed with varying degrees of success (e.g., Feiss et al., 2019; Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). Previous studies have found, for example, that universal prevention programs for depression and anxiety in educational settings are effective immediately after intervention (effect sizes for depression g = 0.21 and for anxiety g = 0.18). Likewise, targeted prevention programs (for youth with risk factors or symptoms) were associated with significantly larger effect sizes compared with universal programs for depression (Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). Overall, school mental health services appear to find a small to medium effect (g = 0.39) in reducing mental health problems. Previous work has found the effect sizes for universal, targeted, and indicated intervention to be, respectively, g = 0.29, g = 0.67, and g = 0.76 (Sanchez et al., 2018). Nevertheless, and in recognition of the relevance of these studies, there is still a need for a larger scientific corpus (stronger and broader empirical evidence) in the field of mental health promotion and prevention in the school setting. For example, some of the tasks yet to be undertaken could include the need to develop and validate prevention programs for vulnerable groups or to conduct studies to analyze what are the effective components of psychological interventions in educational settings. There is still room for improvement.

It is worth noting that there is also a sufficient body of knowledge indicating that some school-based mental health interventions can cause iatrogenic harm (Andrews et al., 2022; Bonell et al., 2015; Guzman-Holst et al., 2022). The mechanisms by which this occurs are not yet well understood, but it seems reasonable to think that having quality work is at least a primary condition. Therefore, we should be cautious about the idea that it is better to implement any intervention than not to do so (Foulkes & Stringaris, 2023).

In accordance with the code of ethics, psychology professionals should use the intervention procedures that have empirical support according to the characteristics of the people seeking help. In general terms, psychological treatments have been shown to be efficacious, effective, and efficient in addressing a wide range of psychological problems (Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021a). Childhood psychological adjustment difficulties must be resolved in the social context of learning and psychological development, as well as in the natural ecosystem where they occur. Moreover, there is evidence that this can be articulated in the educational institutions themselves (Loftus-Rattan et al., 2023). Researchers, policy makers, and psychology practitioners must collaborate to understand what works best for whom, when, why, and under what conditions. This will help to develop more efficacious, efficient, and effective interventions in the future to address the diverse needs of all young people (Durlak et al., 2022). Remember: good psychotherapy saves lives (Knapp, 2020).

PSICE Study: The Road Ahead

Justification

Emotional psychological difficulties (e.g., anxiety, depression) in young people are a public health problem, both because of their prevalence and associated morbidity, and because of the risk of them prolonging into adulthood and the associated consequences. Child and adolescent mental health and its associated problems are a major concern, with great personal, family, school, and social-health repercussions to which psychology and society must respond. Therefore, it is necessary to address this emerging social challenge through research based on empirical evidence.

The general objective of the PSICE Project (for more details, see Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2023) is to improve and optimize strategies for the detection and prevention of emotional problems, as well as access to efficacious, effective, and efficient intervention. On a more specific level, it seeks to examine the efficacy of the Unified Protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents (UP-A) (Ehrenreich-May et al., 2019) in educational settings. The goal is to prevent emotional problems, as well as to improve or optimize social-emotional adjustment, learning processes, and academic performance. Among its specific objectives is to analyze the prevalence rates of difficulties in emotional adjustment in a sample of adolescents from the general population.

Participants

A total of 8,749 students participated in the study from the following autonomous communities: Andalusia, Castilla La Mancha, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, Principality of Asturias, and Valencia. The initial sample was N = 9,267, although a total of n = 264 participants were discarded because they were over 18 years of age; n = 206 participants were discarded due to invalid responses (response infrequency), and n = 48 were discarded due to missing values. The mean age was 14.1 years (SD = 1.6), range 11 to 18 years. Of the total sample, 54.2% (n = 4,740) were defined as girls. The proportion of the sample that reported having Spanish nationality was 91.8%.

Instruments

Different measurement instruments were used (for more details see the work of Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2023). In the present study, only the following were considered: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) adolescent version (Johnson et al., 2002), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) self-report version (Goodman, 1997), and the escala de SENTIA de conducta suicida para adolescentes [SENTIA suicidal behavior scale for adolescents] (Díez-Gómez et al., 2020).

Procedure

The study was approved by the CEImLAR (Clinical Research Ethics Committee of La Rioja). All participants under 18 years of age gave the consent of their legal guardians according to the WHO guidelines. The students were informed at all times of the confidentiality of their answers, as well as the voluntary nature of their participation. The administration of the measurement instruments was carried out collectively, in groups of 15 to 30 students, during school hours, via computer, and in a classroom set up for this purpose under the supervision of a study collaborator.

Results

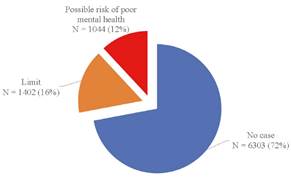

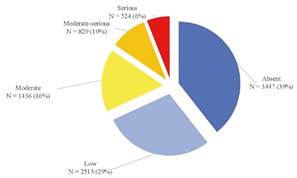

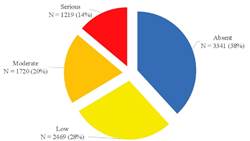

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of emotional and behavioral difficulties by risk levels estimated with the SDQ. Figure 4 shows the risk levels of depressive symptomatology, estimated using the PHQ-9. Figure 5 shows the risk levels for anxiety, estimated using the GAD-7. Table 2 shows the prevalence rates of suicidal behavior.

Figure 3. Prevalence of Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties by Risk Levels Estimated With the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Self-Report Version.

Figure 4. Risk Levels of Depressive Symptomatology Estimated Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) Adolescent Version.

Figure 5. Risk Levels of Anxious Symptomatology Estimated by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7).

Table 2. Prevalence of Suicidal Behavior, Estimated With the SENTIA Scale (Díez-Gómez et al., 2020).

| Items | Affirmative answer (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Have you ever wished you were dead? | 20.8 |

| 2. Have you ever had thoughts of taking your own life? | 16.7 |

| 3. Have you ever planned to take your own life? | 7.5 |

| 4. Have you told anyone that you want to take your own life? | 9 |

| 5. Have you ever tried to take your own life? | 4.9 |

This work is not free of limitations, so the results obtained must be interpreted with caution. Firstly, the sample was selected, with the exception of the region of La Rioja, by means of incidental sampling. Secondly, the information obtained is based on self-reports, with the usual limitations. These barriers may have affected the results found. Nevertheless, this initial and pioneering study in Spain allows us to begin to make informed decisions regarding mental health.

The way Forward: From the River to the Ocean

As mentioned above, mental health is a right to be cared for, promoted, and protected. People, and in particular the most vulnerable groups such as minors, deserve accessible, inclusive, public, and quality psychological care. For this reason, the importance of promoting psychological well-being in educational institutions is defended here, recognizing that childhood and adolescence are sensitive stages of human development and that minors are the present and future pillar on which our society is based.

Stably and consistently replicated findings seem to indicate that mental health problems constitute an educational and social challenge that needs to be addressed. At the same time, the science seems to show that prevention is one of the priority strategies in reducing the prevalence rates and costs associated with psychological problems. There is no doubt that the educational context, for the reasons given above, is an excellent place for the prevention, early detection, and implementation of efficacious, efficient, and effective interventions. If this is true, would it be worthwhile to put in place psychological well-being and mental health services in schools with psychology professionals? Could this workload be assumed by one educational counselor, who may lack any training in psychology, for every 800 students? Or is it the teachers, buried in the emergencies of school and teaching tasks, who have to take responsibility for this situation? Trying to answer these questions places us directly in front of the need for professionals specifically trained in human development, mental health, and behavioral prevention, the areas belonging to the psychology professional. Professionals who have the competencies and training required by law. Professionals who, additionally, must be experts in the optimization of the psychological aspects (e.g., cognitive, behavioral, emotional, motivational) involved in the teaching-learning processes in educational contexts, as well as in the detection, assessment, and intervention in specific educational support needs, with the ultimate goal of promoting the integral development and learning of all students from an inclusive perspective. The basic ethical principle of "first do no harm" (primum non nocere) only continues to point out the urgent need to incorporate psychology professionals in educational institutions under the figure of the educational psychologist.

In line with the above, it is important to establish national mental health policies in schools, within an inclusive, holistic, comprehensive, and multisectoral approach, where intervention in the educational context is an essential foundation based on five fundamental pillars (UNICEF, 2022):

Creating a learning environment that supports mental health and well-being.

Ensuring access to early intervention and mental health services and support.

Promoting the well-being of the teaching staff.

Ensuring the training of educational personnel in mental health and psychosocial support.

Ensuring meaningful collaboration among school, families, and communities to build a safe and nurturing educational environment.

The implementation of school-based mental health services is an imperative need, especially if one takes into account the Inverse Care Law (Tudor Hart, 1971). This law postulates that access to quality medical or social care varies in inverse proportion to its need in the population served, that is, those most in need are least likely to receive care. According to an editorial in The British Journal of Psychiatry (Cuijpers et al., 2023), unfortunately, mental disorders are associated with inequalities in multiple ways. Not only are structural factors such as unemployment and poverty associated with an increased risk of developing mental disorders, but those same social groups also have the least access to subsistence, protection, and effective care. And when the most vulnerable do get support, outcomes are often worse if interventions are not tailored to their lives and circumstances. Improving mental health care is therefore inherently associated with reducing inequalities and poverty.

The ways in which educational systems implement mental health services in schools can be heterogeneous. It is not the purpose of this article to enter into debates about the training and functions of the educational counselor. Nor is it the aim to burden the educational psychology professional with more tasks than he or she already has or to place him or her as solely responsible for the psychological well-being and mental health of an entire educational community. This paper simply aims to invite reflection and draw attention to an approximate picture of the current situation of the mental health of our children, as well as to explain the existence of models and strategies that have sufficient empirical evidence to improve it from the educational context. Nonetheless, we must work on the incorporation of psychology professionals in educational institutions, with the aim of improving the welfare of the educational community, emotional education, and attention to diversity. In this sense, although this has been demanded for some time from both the academic and professional spheres (COP, 2015), it has not been until very recently that it is being considered by the relevant public administrations2.

In spite of the above, several experts have developed various proposals in the last decade. To our knowledge, the most recent one has been made by Garaigordobil (2023). This author, in line with what was previously established by the COP (2015), states that the educational psychologist is a key figure in the functional and balanced development of an educational institution at all educational stages. Their priority function is to attend to and promote psychological development, psychological and emotional well-being, and mental health in all agents of the educational system (students, families, and teachers). To achieve this, adequate time and space must be set aside for the development of assessment and intervention programs aimed at improving the socioemotional competencies and well-being of teachers, students, and families. And in order to reserve these times and spaces, it is necessary to increase the current ratio of psychology professional/person served. Garaigordobil (2023) classifies the functions of the educational psychology professional according to the recipient of the services:

– Students: a) assess (and diagnose if necessary), b) prevent difficulties and problems; c) optimize the development of their abilities; and d) intervene when difficulties or problems appear.

– Teachers: a) report the results of collective assessments and/or individual diagnoses; b) advise and collaborate, for example, in the analysis of situations, in the teaching-learning processes, in the attention to diversity; c) train teachers by organizing training courses and conferences; d) provide emotional support to teachers to promote their well-being and mental health; and e) research topics related to educational psychology.

– Families: a) provide the family with diagnostic information and advice on how to handle problematic situations; b) train families on how to optimize development, on child and adolescent problems, etc.; and c) carry out psychoeducational interventions with the family group and/or refer to external professionals and provide follow-up.

We have examples of models implemented in other countries (Loftus-Rattan et al., 2023). It should be ensured that such interventions are inclusive, accessible, and based on scientific evidence, using standardized protocols that work for a large population, especially if minors are involved. It remains a priority, for example, to develop and validate empirically supported programs for the prevention of suicidal and other problem behaviors in childhood and adolescence, as well as to determine which treatments are effective, which components, and for whom. From another point of view, and in accordance with the code of ethics, as a science that deals with the study of the person and behavior, psychology must be based on empirical evidence to support the use of its techniques and procedures. Psychology professionals must promote and implement actions that have empirical support according to current scientific standards in order to make informed decisions. For example, prevention models, screening strategies, and psychological interventions must be empirically supported. Whether we like it or not, rigor and quality are necessary and desirable both for the profession itself and for users and society. This should not be a matter of debate.

It goes without saying that, faced with this scenario, action is needed. This is not a road we can travel alone. Accordingly, we must assume our co-responsibility, which belongs to all of us, and address this public health problem with rigor, ethics, and commitment to action in order to move in the same direction, prioritizing the care and well-being of the people who suffer. Joint policies, plans, and actions must be developed, in the case of Spain and many other countries, leading to a true national mental health plan. Mental health problems can be prevented, but using resources and policies that promote and finance prevention programs. These must be created. And psychology must take the lead.

Promoting, protecting, and caring for the mental health of the entire population, but particularly the most vulnerable, is a constitutional duty. It is time to take action; we cannot ignore this reality. It is time to generate hope through action, with the firm conviction that where there is no hope, we must build it.