Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versión On-line ISSN 2173-9161versión impresa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.28 no.5 Madrid sep./oct. 2006

Cranio-facial osteomas: report of 3 cases and review of the literature

Osteomas cráneo-faciales: presentación de 3 casos y revisión de la literatura

I. Peña González1, S. Llorente Pendás2, C. Rodríguez Recio1, L.M. Junquera Gutiérrez2, J.C. De Vicente Rodríguez3

1 Médico Residente.

2 Médico Adjunto.

3 Jefe de Sección.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial.

Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, España

Dirección para correspondencia

ABSTRACT

Introduction. Osteomas are benign, slow-growing tumors

that are located principally in the cranio-maxillo-facial region. Treatment of

these silent lesions has resulted in controversy, as their potential for

becoming malignant has not been demonstrated.

Material and Methods. Three

somewhat uncommon cases of craniofacial osteomas located in frontal, ethmoid and

mandible bones are presented.

Discussion. A revision of the literature is

carried out, and a reasoned comparison is made of the attitude taken in the

cases presented. The advantages and disadvantages of the treatment carried out

are discussed.

Conclusions. Each case should be assessed individually in

order to decide how it should be dealt with, taking into account the risk

derived from the surgery as well as the risk derived from a wait and watch

strategy. The type of surgery for these tumors is determined by their size and

location.

Key words: Osteomas; Frontal; Orbital; Mandibular.

RESUMEN

Introducción. Los

osteomas son tumores óseos benignos de crecimiento lento, localizados

principalmente en la región cráneo-máxilofacial. El tratamiento de las

lesiones silentes suscita controversia pues no se ha evidenciado su poder de

malignización.

Material y Método. Se presentan 3 casos poco

habituales de osteomas craneofaciales localizados en los huesos frontal,

etmoides y mandibula.

Discusión. Se realiza una revisión de la

literatura realizando una comparativa razonada de la actitud tomada en los casos

presentados, discutiendo las ventajas e inconvenientes de los tratamientos

realizados.

Conclusiones. Se debe realizar una valoración

individualizada de cada caso para decidir su manejo, teniendo en cuenta el

riesgo derivado de la intervención así como el riesgo derivado de la conducta

expectante. El tipo de cirugía en estos tumores vendrá determinada por su

tamaño y localización.

Palabras clave: Osteomas; Frontal; Orbitario; Mandibular.

Introduction

Osteomas are benign slowgrowing bone tumors that are located principally in the cranio-maxillo-facial region. They can be central (endosteal) or peripheral (periosteal). Central osteomas are located more frequently in the frontal and ethmoid bones,4 while peripheral ones are located, in a greater proportion, in the paranasal sinuses.4,6,7 They can be solitary or multiple masses and they are generally asymptomatic. The appearance of multiple masses is suggestive of a syndrome such as Gardener syndrome.4,11 Given the rare recurrenceof these tumors, they should initially be treated with conservative surgery. We present 3 cases of osteomas with unusual characteristics as regards size or location, and the pathology within the maxillofacial area is revised.

Material and Method

Case 1

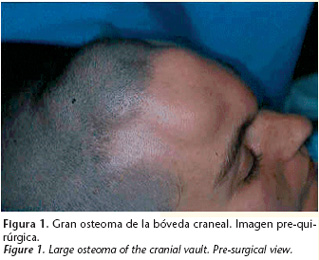

Female, 33 years old, came to our department for assessment of an asymptomatic mass that was hard and growing progressively, and which was causing a large craniofacial deformity (Fig. 1). The computerized tomography (CT) showed the presence of bone tumor in the external cortical surface of the frontal bone that had no relation to the sinus (Fig. 2). With the clinico-radiological diagnosis of peripheral frontal bone osteoma, the patient underwent surgery, and a bicoronal approach (Fig. 3) was carried out and excision by means of drilling and osteotomies was carried out, until an internal healthy cortical layer was reached. After a following of a year and a half, there has been no sign of recurrence (Fig. 4).

Case 2

Male patient, 23 years old, with occasional blurred vision for 4 months before consultation. A radiograph was carried out using Waters view, and a radiopaque mass was observed in the right orbit. The CT scan showed a bone mass by the lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone that was not related to the ethmoidal sinus (Fig. 5).

The resection of the tumor was carried out by means of a 30º endoscopy, through a minimal superior transpalpebral incision and with the aid of a small chisel. A small defect was generated in the lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone that, given its size, did not require reconstruction. There was no evidence of tumor recurrence during the three year follow-up.

Case 3

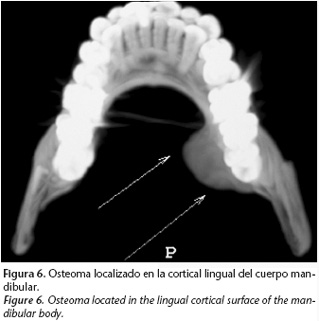

Female, 23 years old, requested assessment as a result of a mandibular tumor-like mass that had been evolving for various year, but which had been growing progressively for the previous two months. The mass, which had a stony consistency, could be felt by the lingual cortical surface of the mandibular body, and it extended towards the basal structure of the mandible. The orthopantomography showed how it was extending in a mesiodistal direction from the second premolar to the second molar, there being no involvement here.

The CT scan showed a bone mass, that was affecting the internal mandibular cortical surface, but not the external cortical surface, which was compatible with a peripheral osteoma (Fig. 6). The surgical approach was carried out intraorally through two incisions, one lingual and the other vestibular. The resection of the tumor was carried out by means of drilling and chisel osteotomies. There have been no signs of recurrence during the two-year follow-up.

Discussion

Osteomas are benign tumors. They generally grow slowly and they are typical of the cranio-maxillo-facial area. They can be central or peripheral. Their incidence and real prevalence is unknown as, in most cases, they are asymptomatic. It is the most common benign neoplasm of the paranasal sinuses1 and orbit2 and they may present at any age, in most cases between the 2nd and 5th decades in life.3,4 Central osteomas are usually located in the frontal, ethmoid and mandible bones4,5 while peripheral osteomas are usually found in the paranasal sinuses.4,6,7 They tend to be chance radiological findings.3 Normally they are solitary masses3,4,6,7 and when they present in a multiple form we should rule out the presence of a complex syndrome such as Gardner syndrome.4

Osteomas of the cranial vault are extremely rare.8 In fact, we have not been able to find in the literature an osteoma with similar characteristics to this first case of ours. When they are located in the frontal bone, patients tend to present with a cranial deformity and with chiefly nocturnal headaches.8 Our patient did not have any symptoms. However, the deformity produced by the tumor was aesthetically unacceptable.

The orbit is also an infrequent site,5 representing between 0.9-5.1% of all tumors of the orbit9 with the most common origin being in the adjacent sinuses5 (frontal, ethmoid and maxillary, in order of frequency).10 Pure orbital osteomas (proceeding from the cavity walls, with no relation to the sinuses) are even more rare.9 Our second case belongs to this group, as it originated from the lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone. Pure osteomas of the orbit appear in the form of orbital dystopia, generally as progressive proptosis11,12 that can be accompanied by diplopia.11 Normally the symptoms appear during the early stages of tumor progression, which allows early diagnosis.13 In our cases the blurred vision of the patient permitted rapid detection.

Peripheral osteomas of the mandible are uncommon,6, 7 and they are found more commonly in the vestibular cortical and basal structures.7 Peripheral osteomas of the mandible tend to become symptomatic when they grow beyond the limit of the bone where they are situated, causing asymmetry or facial deformity.6,7,8

Given that the clinical symptoms are not pathognomonic of these tumors, the first step would be plain radiographic study11 or an orthopantomography.3, 6 CT is fundamental6 for determining the location and extension of the lesion and for planning the most appropriate surgery.

The differential diagnosis should be carried out with numerous entities: torus, exostosis, condensing osteitis4 odontoma, focal sclerosing osteomyelitis,3,4 hyperostotic meningioma, osteoblastoma,13 osteochondroma,3, 11 Pagets disease,3 osteochondritis, subperiosteal hematoma, fibrous displasia,2, 3,13 ossifying fibroma,3,13 and osteosarcoma.3, 5

With regard to the management of these tumors, surgery is necessary for symptomatic osteomas that are growing continuously, and when there are complications that are not susceptible to medical treatment or that are resistant to it. And also, when the aesthetic aspect is displeasing to the patient or through choice (cancerophobia). The most controversial issue involves osteomas that are asymptomatic and the attitude that should be taken, given that malignization has not been described. The individualized assessmentof the size and site of the tumor are essential for determining the possible complications derived from a wait and see approach and those derived from surgery.

Some authors1,10,12 prefer annual or biennial following of asymptomatic osteomas, while opting for surgery for certain sites such as the orbital apex13 or sphenoid sinuses.1,10,12 Given the size that the tumor had acquired in the first case, surgical treatment was decided on, as radiologic following would have resulted in an increase in size of the osteoma and, as a result, in more extensive surgery. Authors such as Becelli et al9 prefer excision of all endo-orbital osteomas because of the risk posed by growth to the optic fascicle and to eye vessels. This attitude could be quite excessive if it is not taken into account that some intraorbital osteomas require surgery entailing considerable operative morbidity, although we were able to use endoscopic surgery in the second case. With regard to asymptomatic osteomas of the mandible, there are various opinions. Some authors are in favor of surgery3 while others are more conservative and they only use surgery for those that are symptomatic or that are actively growing. 6 In the third case of ours, surgical treatment was decided on, given that the patient reported active growth of the tumor, size in addition to site, and that an intraoral approach was possible.

Once it has been established that surgical treatment is the attitude of choice, the type of surgery and method of approach are conditioned by the size and site of the tumor, and by the skills of the surgical team, in the knowledge that recurrence is possible1,2,12 although rare.3,7,12,13 It has to be taken into account that osteomas grow from the center outwards, so that partial resection, while leaving a peripheral area, will lead to recurrence very rarely, and that therefore, complete resection in critical areas is not necessary when the risk of surgical damage is high.12,13

In the case of frontal bone osteomas, an open approach tends to be carried out,8 as in the first case of ours in which a bicoronal approach was decided on, given the large size of the tumor. This was followed by drilling to the internal cortical structure to ensure the elimination of the center of the tumor. Classically, open approaches have been used for the resection of orbital osteomas.9,13 Currently, endoscopic surgery allows the tumor to be approached with minimum surgical morbidity. Among the advantages, of note are better aesthetic results, less pain, less postsurgical edema, fewer intraoperative complications and reduced hospitalization time. Among the disadvantages to be considered are the reduced visual field, the need for greater surgical skill, and its limited use depending on the location of the tumor. If we are not careful, fistulas of cephalorrhachidian liquid may arise, which can also occur during open approaches,13 and there may be loss of vision.14 In order to reduce these risks, and to increase the field of vision, the use of 30 degree endoscopes is recommended.1

In the case of mandibular osteomas, the intraoral approach is preferable to the extraoral, as there is less surgical morbidity. We consider that a basal location is not mandatory for an external approach. In our case, this could be carried out intraorally, although a double vestibular and lingual approach was needed.

Conclusion

Osteomas are tumors with unpredictable growth and with practically no probability of malignant transformation. As a result,management of asymptomatic masses is controversial. Each case should be assessed individually according to the size, location, the risk of the surgery, and the risk of a watch and wait strategy, in order to decide on the therapeutic attitude. As a result of the development of endoscopic surgery, for certain cases this represents a valid alternative.

![]() Correspondencia:

Correspondencia:

Ignacio Peña González

C/ Celestino Villamil s/n

33006 Oviedo, Asturias, España

e-mail: paego_maxilo@hotmail.com

Recibido: 08.05.2006

Aceptado: 06.10.06

References

1. Huang HM, Liu CM, Lin KN, Chen HT. gigant ethmoid osteoma with orbital extension, a nasoendoscopic approach using an intranasal drill. Laryngoscope 2001;111:430-2. [ Links ]

2. Fu YS, Perzin KH. Non-epitelial tumors of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx. A clinicopathological study ii. Osseus and fibro-osseus lesions, including osteoma, fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, osteoblastoma, giant cell tumor and osteosarcoma. Cancer 1974;33:1289-305. [ Links ]

3. Longo F, Califano L, De Maria G, Ciccarelli R. Solitary osteoma of the Mandibular Ramus: Report of a Case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;59:698-700. [ Links ]

4. López Arranz JS, De Vicente Rodríguez JC, Junquera Gütiérrez LM. Patología Quirúrgica Maxilofacial. Síntesis Madrid 1998;p 221. [ Links ]

5. Gillman GS, Lampe HB, Allen LH. orbitoethmoid osteom. Case report of an uncommon presentation of an uncommon tumor. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;117:S218-S20. [ Links ]

6. Bodner L, Gatot A, Sion-Vardy N, Fliss D M. Peripheral osteoma of the mandibular ascending ramus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998;56:1446-9. [ Links ]

7. Kaplan I, Calderon S, Buchner A. Peripheral osteoma of the mandible: a study of 10 new cases and analysis of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994;52:467- 70. [ Links ]

8. Eppley BL, Kim W, Sadove AM. Large osteomas of the cranial vault. J Craniofac Surg 2003;14:97-100. [ Links ]

9. Becelli R, Santamaria S, Saterel A, Carboni A, Ianetti G. Endo-orbital osteoma: two case reports.J Craniofac Surg 2002;13:493-6. [ Links ]

10. Byron JB. Head and Neck Surgery Otolaryngology. Lippincott-Raven. USA. 2ª Ed. 1998;2:1478. [ Links ]

11. Alper M, Gürler T, Totan S, Bilkay U, Songür E, Mutluer S. Intraorbital osteoma and surgical strategy. J Craniofac Surg 1998;9:464-7. [ Links ]

12. Selva D, White VA, O´Conell JX, Rootman J. Primary bone tumors of the orbit. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:328-42. [ Links ]

13. Ciappetta P, Delfini R, Iannetti G, Salvati M, Raco A. Surgical strategies in the treatment of symtomatic osteomas of the orbital walls. Neurosurg 1992;31:628- 35. [ Links ]

14. Akmansu H, Eryilmaz A, Dagli M, Korkmaz H. Endoscopic removal of paranasal sinus osteoma: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;60:230-2. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en