Fear of childbirth (FOC) can negatively impact both mothers and infants. Both nulliparous and parous women can have problems with mental health (especially depression and anxiety), and more need for psychiatric care and medication (Rouhe et al., 2011). Also, a systematic review reported on the association between FOC and obstetric complications, such as prolonged labour, use of epidural, instrumental birth, and posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth (Dencker et al., 2019). About 15% of primiparous women and 7% of multiparous women have high FOC (Joki-Begi et al., 2013; Kuljanac et al., 2023).

Elevated FOC is associated with some personality dispositions, such as trait anxiety, anxious sensitivity (Joki-Begi et al., 2013), neuroticism (Handelzalts et al., 2015), and perfectionism (Kuljanac et al., 2023). Recent literature was focused on intolerance to uncertainty (IU), an important transdiagnostic factor for anxiety and depression disorders (Mahoney & McEvoy, 2012), and "key construct related to worry" (Birrell et al., 2011, pp. 1206). The definition of the IU has changed throughout the years. The newest conceptualisation of IU emphasises that IU could present the latent fear of the unknown or tendency to perceive the occurrence of a negative event as threatening regardless of the possibility of its occurrence (Carleton, 2012). Birrell et al. (2011), in a review of the latent structure of the construct, suggested that two factors could be identified: the desire for predictability and an active engagement in seeking certainty, and the paralysis of cognition and action in the face of uncertainty.

Individuals high in IU tend to experience increased anxiety in uncertain situations, and childbirth is one of them. Although childbirth is a physiological process, it can be unpredictable and uncontrollable (Wijma et al., 1998). The IU was shown as a significant predictor of FOC in pregnant women (Rondung et al., 2018), but the evidence is still scarce, and findings about that relation in women are still inconsistent. For example, IU was predictor of fear of childbirth in pregnant women in Sweden (Rondung et al., 2018), but not in primiparous and multiparous pregnant women in Croatia (Kuljanac et al., 2023). Also, little is known about mediators or the relation between the FOC and IU.

Individuals with high IU tend to seek predictability (Birrell et al., 2011), so they could actively engage in various actions that can increase the predictability of a situation and decrease uncertainty. It is possible that preparedness for childbirth could decrease FOC in women with high IU. We hypothesised that the association between IU and FOC could be mediated through perceived preparedness for childbirth in pregnant women. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the mediating role of perceived preparedness for childbirth between IU and FOC in primiparous and multiparous pregnant women.

Method

Participants

In this cross-sectional study, 292 women participated, of which 168 were primiparous and 124 were multiparous pregnant women. The majority of the participants were highly educated (66.1% of nulliparous, 64.5% of multiparous), lived in an urban place (83.3% of nulliparous, 86.2% of multiparous), and perceived their socioeconomic status as average (61.3% of nulliparous, 57.8% of multiparous). Also, almost all pregnant women were married or cohabitating (94.1 % of nulliparous and 100% of multiparous) and employed (98.2% of nulliparous and 97.5% of multiparous). The sample was described previously in detail (Kuljanac et al., 2023).

Instruments

FOC was measured with Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire (W-DEQ; Wijma et al., 1998) using version A, which measures expectations before childbirth. Two items regarding thoughts about death and harming the baby were excluded; therefore, the scale consisted of 31 items. Results could range from 0 to 155, so a higher result indicates higher FOC, but a clinically significant score was equal to 85 or above (Ryding et al., 1998). In this study, Cronbach α was .92.

Intolerance of uncertainty was measured with the 11-item Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS; Freeston et al., 1994). Although the scale consists of two subscales, Prospective and Inhibitory Anxiety, we obtained a one-factor solution and used only the total score. Higher scores indicate higher intolerance of uncertainty, and the theoretical range is from 1 to 55. In this study, Cronbach α was .92.

Perceived preparedness for childbirth was measured with only one item in all three groups: "How prepared do you feel for childbirth?", and answers were on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely), so a higher score indicated higher preparedness.

Procedure

Pregnant women filled out questionnaires at the prenatal clinic while waiting for regular prenatal checkups. The study was cross-sectional and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Catholic University of Croatia and by the Ethical Committee of the University Hospital Center Sisters of Mercy (see details in Kuljanac et al., 2023).

Statistical Analyses

The Pearson coefficient was used to examine correlations between variables in the software SPSS 21.0 for Windows. Mediation analyses were conducted in Process Macro 3.2.01 for SPSS (Hayes, 2013) using model 4. In the mediation analysis, the predictor was IU, the criterion variable was FOC, and preparedness for childbirth was a mediator. The bootstrap method (5,000 samples) was used, and the confidence interval (CI) was 95%. The effect was significant if the confidence interval did not contain zero. Non-standardised estimates were calculated and presented.

Results

The descriptive data were examined for all variables in primiparous and multiparous women (Table 1). Of the sample, 15.5% of primiparous and 7.3% of multiparous women had high FOC (score 85 and above). Both groups of pregnant women had moderate levels of IU and low to moderate levels of FOC, and mean levels did not significantly differ between primimarous and multiparous women. However, multiparous women reported significantly better preparedness for childbirth than primiparous women (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive Data for Intolerance of Uncertainty, Perceived Preparedness for Childbirth, and Fear of Childbirth.

Note.IU = intolerance of uncertainty; PPC = perceived preparedness for childbirth; FOC = fear of childbirth.

*p = .046

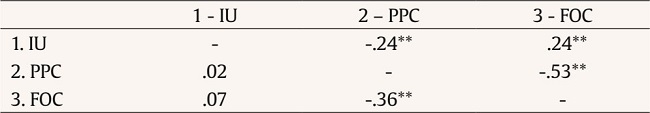

The association between IU, FOC, and perceived preparedness for childbirth were examined in pregnant primiparous and pregnant multiparous women (Table 2). In primiparous women, higher IU was correlated with higher FOC, while lower perceived preparedness for childbirth was correlated with higher IU and FOC. In multiparous women, IU was not associated with FOC and perceived preparedness for childbirth, therefore, mediation analyses could not be performed in this subsample.

Table 2. Correlation of Intolerance of Uncertainty, Perceived Preparedness for Childbirth, and Fear of Childbirth in Primiparous (n = 168) (above diagonal) and Multiparous Women (n = 124) (below diagonal).

Note.IU = intolerance of uncertainty; PPC = perceived preparedness for childbirth; FOC = fear of childbirth.

**p < .01.

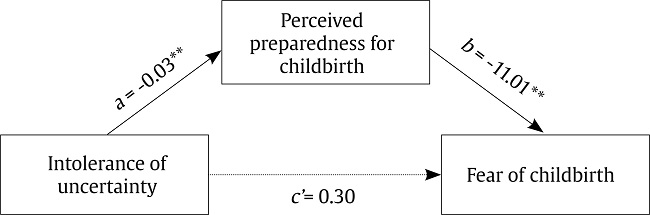

A mediation analysis was conducted on primiparous women, where IU was the predictor, perceived preparedness for childbirth the mediator, and FOC the outcome (Figure 1). In primiparous pregnant women, IU predicted fear of childbirth only indirectly (B = 0.31, SE = 0.12, CI [.10, .58]) through perceived preparedness for childbirth and not directly (B = 0.30, SE = 0.17, CI [-.04, .64]). Therefore, perceived preparedness for childbirth was a full mediator between IU and FOC (Figure 1). The model explained 29.4% of the variance of FOC.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine whether preparedness for childbirth was a mediator between IU and FOC in primiparous and multiparous women. Results showed that IU predicted FOC only indirectly through lower perceived preparedness for childbirth in primiparous pregnant women. On the other hand, in multiparous women, IU was neither associated with FOC nor with preparedness for childbirth, so the mediation analysis could not be conducted.

In pregnant primiparous women, i.e., women with no previous experience of childbirth, preparedness for childbirth was a significant mediator between IU and FOC. Women with high intolerance of uncertainty also perceived that they were unprepared for delivery which predicted elevated FOC. These results align with the theoretical framework of IU, claiming that preparedness and seeking information could decrease worry and anxiety in individuals with high IU (Birrell et al., 2011). Contrary to primiparous women, IU was not correlated with FOC in multiparous women. The latter is in line with previous findings implying that previous experiences, and not personality dispositions, were more relevant predictors for high FOC (Jokić-Begić et al., 2014; Kuljanac et al., 2023).

These findings have some practical implications. Preventive programs for FOC should aim at first-time pregnant and multiparous women. As preparedness is important in all groups of women, preventive programs and courses should especially emphasise FOC and empower women to cope with it. Giving adequate information regarding childbirth and addressing and diminishing fears and concerns is crucial. On the other hand, interventions regarding reducing FOC in multiparous women should focus on their previous childbirth experiences, especially if it was perceived as traumatic. The risk of not providing preventive and interventive programs could be very high – it could impact women's well-being or their decision not to have (more) children.

Limitations of this study should be considered. First, this study was cross-sectional, and a longitudinal design should be applied in the future to test full mediation analysis. Second, we have used only one question to assess the preparedness for childbirth, so it is recommended to use a questionnaire in future studies, and a recently developed Childbirth Readiness Scale (Mengmei et al., 2022) sounds a promising tool for such a purpose. Third, the sample was convenient and consisted of highly educated participants with average socioeconomic status living in urban areas with their partners (especially pregnant women). Therefore, the results could be somewhat different if participants were women who did not have access to information and courses regarding childbirth (e.g., minority groups), although most of the prenatal classes in Croatia are free. Finally, other underlying mechanisms between intolerance of uncertainty and fear of childbirth should be examined to elucidate the complexity of these relations. Also, longitudinal design studies should be conducted in order to follow non-pregnant women throughout their pregnancy. Additionally, it would be beneficial to examine how preparedness and some preventive interventions could diminish FOC during the first pregnancy. Further research regarding effective treatment for FOC tailored to women's personality characteristics and previous experience and expectations is needed for all groups of women.