Introduction

Mattering is the perception of being important to other people (DeForge & Barclay, 1997), either to significant others (e.g., family, friends) – interpersonal mattering – or to the community/society – societal mattering (DeForge & Barclay, 1997; Sari & Karaman, 2018). The concept of general mattering was first introduced by Rosenberg and McCullough (1981), who described it as the feeling that one is an object of interest and concern to others, and that one is important and wanted, being therefore an important component of self-concept. The authors suggested that there are five main components of mattering: attention (the perception of being noticed), importance (the belief that someone cares), ego extension (the belief that others will be proud and/or empathetic), dependence (the perception of being needed by someone), and appreciation (the perception of being appreciated by others) (Rosenberg & McCullough, 1981).

Thus, mattering is a vital psychological resource for human condition. In fact, individuals who do not perceive themselves as mattering to others tend to have difficulties in personal significance, connection, and social acceptability, three essential aspects for the development of the human being (Flett, 2022). In contrast, individuals who have an unconditional sense of mattering have internal resources to deal with the challenges of everyday life. Hence, mattering plays a significant role as a buffer in the presence of stressors (Flett, 2022), supporting its relevance for individual well-being and psychosocial adjustment.

Literature has shown several positive associations between mattering and outcomes, such as social support, self-esteem, quality of life, and positive affect (Cha, 2016; Davis et al., 2019; Flett et al., 2023; Taylor & Turner, 2001). On the other hand, mattering has been found to be negatively associated with loneliness (Caetano et al., 2022; Flett et al., 2023), rumination, self-criticism, and self-hate (Flett et al., 2021). Rosenberg and McCullough (1981) conducted a study with adolescents and the results revealed that those who did not feel mattering to their parents reported negative outcomes in various dimensions of mental health, including depression and anxiety (Rosenberg & McCullough, 1981). A more recent study with early adolescents showed that mattering is also negatively associated with negative affect, shame, and depression (Flett et al., 2023). Numerous studies stated that general mattering was inversely associated with depression (Cha, 2016; Davis et al., 2019; Nash et al., 2015). In addition, Taylor and Turner (2001) found that changes in mattering were predictive of changes in depression over time, but only for women, with a higher perception of mattering predicting lower levels of depressive symptoms.

Given its clinical significance, mattering has been further explored in different contexts and some measures have been developed to assess this concept, such as, e.g., Mattering Index (Elliott et al., 2004) or Anti-Mattering Scale (Flett et al., 2022). The first known instrument was the General Mattering Scale (GMS; Marcus, 1991) and it was developed based on Rosenberg and McCullough's (1981) theoretical assumptions, considering the five components of mattering. This unidimensional scale is composed of five items (e.g., "How important do you feel you are to other people?") and assesses individuals' perceptions or beliefs that they are important to others, others pay attention to them, others would miss them, others are interested in what they say, and that others depend on them.

DeForge and Barclay (1997) conducted a study with a sample of 199 homeless men and found that the GMS was a reliable measure (Cronbach's alpha of .85) and suitable to use in research. Later, another study evaluated mattering within the context of job satisfaction and conducted a factor analysis using the GMS (Connolly & Myers, 2003). The authors removed item 5 due to a lower factor loading (.60) compared to other items (approximately .80) and found an overall Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .87. Ever since, several validations studies were conducted, including validation of the GMS to American (Davis et al., 2019), Ghana (Stephen Lenz et al., 2018), and Turkish populations (Haktanir et al., 2016), and these studies confirmed that GMS is a unidimensional, reliable and valid measure, with good internal consistency (ω = .84; α ≥ .70; α = .82; Davis et al., 2019; Haktanir et al., 2016; Stephen Lenz et al., 2018).

The GMS has also been evaluated in diverse populations including adults (Taylor & Turner, 2001), women recovering from breast cancer (Davis et al., 2019), students (Haktanir et al., 2016), among others. Gender differences concerning general mattering have been reported, with women presenting higher levels of mattering than men (Taylor & Turner, 2001). Also, as mentioned, the predictive role of mattering in depressive symptoms was found to be significant only for women (Taylor & Turner, 2001), highlighting the importance that this construct can particularly have for women.

The Present Study

The transition to motherhood is a unique time in women's life when they face multiple changes and challenges (Kanotra et al., 2007). The arrival of a baby, the adaptation to a new role and the readjustment of their own identity can also bring challenges to women's interpersonal relationships. In the postpartum period, women often report reduced social contact and feeling isolated and unsatisfied with the quality of their relationships (Lee et al., 2019). This, in turn, can influence how women perceive themselves in their interpersonal relationships and the importance they have for others. Hence, mattering can have an important role in women's experience during the postpartum period. However, this concept has been relatively unexplored in this population. To our knowledge, there is only one study about the relationship between mattering and postpartum depression (Caetano et al., 2022). This study showed that lower levels of mattering contributed to higher levels of depressive symptoms in postpartum women, and that this association not only occurs directly, but also indirectly, through the role of loneliness (Caetano et al., 2022). Besides the limited number of studies on mattering in postpartum women, there is a lack of validated instruments for the Portuguese population assessing mattering in this phase of women's lives. This represents a limitation in the current literature that needs to be addressed. Several studies have addressed the importance of mattering for mental health, in the general population, but few have explored its relevance in a particularly vulnerable period of life as the postpartum period (Caetano et al., 2022). Thus, the aim of the current study is to validate the GMS in Portuguese population and to explore its psychometric characteristics in a sample of postpartum women.

Method

Procedures

This study was part of a wider project aimed to understand women's emotional experiences during the postpartum period, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of University of Coimbra. Adult Portuguese women (18 years or older) in the postpartum period (up to 12 months after childbirth) were eligible to participate in this study. The sample was collected through online advertisements on social media websites (e.g., Facebook) and in thematic forums (e.g., https://demaeparamae.pt/) between June 2020 and March 2021. The research team created a Facebook page for dissemination of the study and conducted unpaid and paid boosting campaigns targeting Portuguese women between 18 and 45 years of age with interest in maternity-related topics. A weblink to the online survey (hosted on LimeSurvey®) was provided, and participants were informed about the study aims, the inclusion criteria, the guarantee of confidentiality and anonymity, and the voluntary nature of their participation. After giving their informed consent by answering a question about their agreement to participate, women were given access to the self-report questionnaires.

Translation Process

Permission to translate and adapt the GMS to Portuguese was requested from the author of the original scale, and a forward-backward translation process was conducted to obtain the Portuguese version. First, two researchers independently translated the GMS items to Portuguese and compared their translations. Discrepancies were discussed and a consensus on a final version was reached. Then, a third researcher who was fluent in English translated the items back into English. Finally, the back-translated version was compared with the original version, and no differences were found.

Measures

A sociodemographic and clinical form was used to collect participants' sociodemographic (e.g., age, marital status) and clinical (e.g., history of psychiatric/psychological problems) information.

The GMS (Marcus, 1991) was used to assess general mattering. This instrument is composed of 5 items (e.g., "How important do you feel you are to other people?"), answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The total score can range between 5 and 20, with higher scores indicating a higher perception of mattering to others.

The Portuguese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Areias et al., 1996) was used to assess depressive symptoms. The EPDS comprises 10 items (e.g., "I have felt sad or miserable") answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The total score can range between 0 and 30, and higher scores are indicative of more severe depressive symptoms. In Portuguese validation studies, a score higher than 9 indicates the presence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms. The Cronbach's alpha value in this sample was .90.

The Portuguese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety Subscale (HADS-A; Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2007) was applied. The HADS-A is a 7-item subscale (e.g., "Worrying thoughts go through my mind") that are answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The total score for this subscale can range between 0 and 21. Higher scores suggest higher levels of anxiety symptoms. The Cronbach's alpha value in this sample was .86.

The Portuguese version of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised (PDPI-R; Alves et al., 2018) was used to assess self-esteem and social support. PDPI-R items concerning self-esteem (3 items, e.g., "Do you feel good about yourself?") and social support (12 items, e.g., "Do you believe that you receive adequate emotional support from your partner?") were used and were answered on a dichotomic scale (No = 0 or Yes = 1), with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-esteem and higher levels of social support.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, version 25.0) and the software Analysis of Moment Structures (IBM SPSS AMOS, version 25.0). Descriptive statistics were computed for sample characterization and to characterize items in terms of their distribution. Pearson bivariate correlations between the GMS items were also computed (effect sizes were considered small, r ≥ .10, medium, r ≥ .30, or large, r ≥ .50; Cohen, 1992). Confirmatory factor analysis with maximum likelihood estimation was conducted to explore the unidimensionality of the GMS. Preliminary assumptions were tested (collinearity and normality). Collinearity between items was not present, as tolerance values were higher than 0.10 and VIF values were lower than 10.0, and normality of data was confirmed by examining the values of skewness (< 3) and kurtosis (< 10) (Kline, 2011). Goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed through the following indicators: the overall chi-squared index (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR). A good model fit would be indicated by a nonsignificant χ2 (p > .05), CFI ≥ .90, RMSEA ≤ .10, and SRMR ≤ .10 (Hu & Bentler 1999; Marôco, 2010). Internal consistency reliability was estimated using Cronbach's alpha for the total score and for the total score excluding each item. Correlations and corrected correlations were calculated for each item and for the total score. To explore the convergent validity of the GMS, Pearson correlations were calculated between the total score of the GMS and other instruments that measure distinct constructs but are expected to have associations with general mattering.

Results

Participants' Characteristics

The sample comprised 532 women in the postpartum period, with an average age of 32.99 years (SD = 4.94; range 19-49). Most participants were married or in a relationship (n = 492, 92.5%), had university studies (n = 366, 68.8%), were currently employed (n = 460, 86.5%) and were living in an urban area (n = 397, 74.6%). This was the first child for most women (n = 363, 68.2%), and the average infant's age was 5.23 months (SD = 3.37, range 0-12 months). Approximately 31.4% of the sample (n = 167) had a history of psychiatric or psychological problems, and 37% (n = 197) had received previous psychiatric or psychological treatment.

Distributional Characteristics of Items

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the five items of the GMS, as well as skewness and kurtosis values. There was at least one participant selecting each response option for all items. Skewness and kurtosis values suggest that the items are characterized by a normal distribution.

Construct Validity

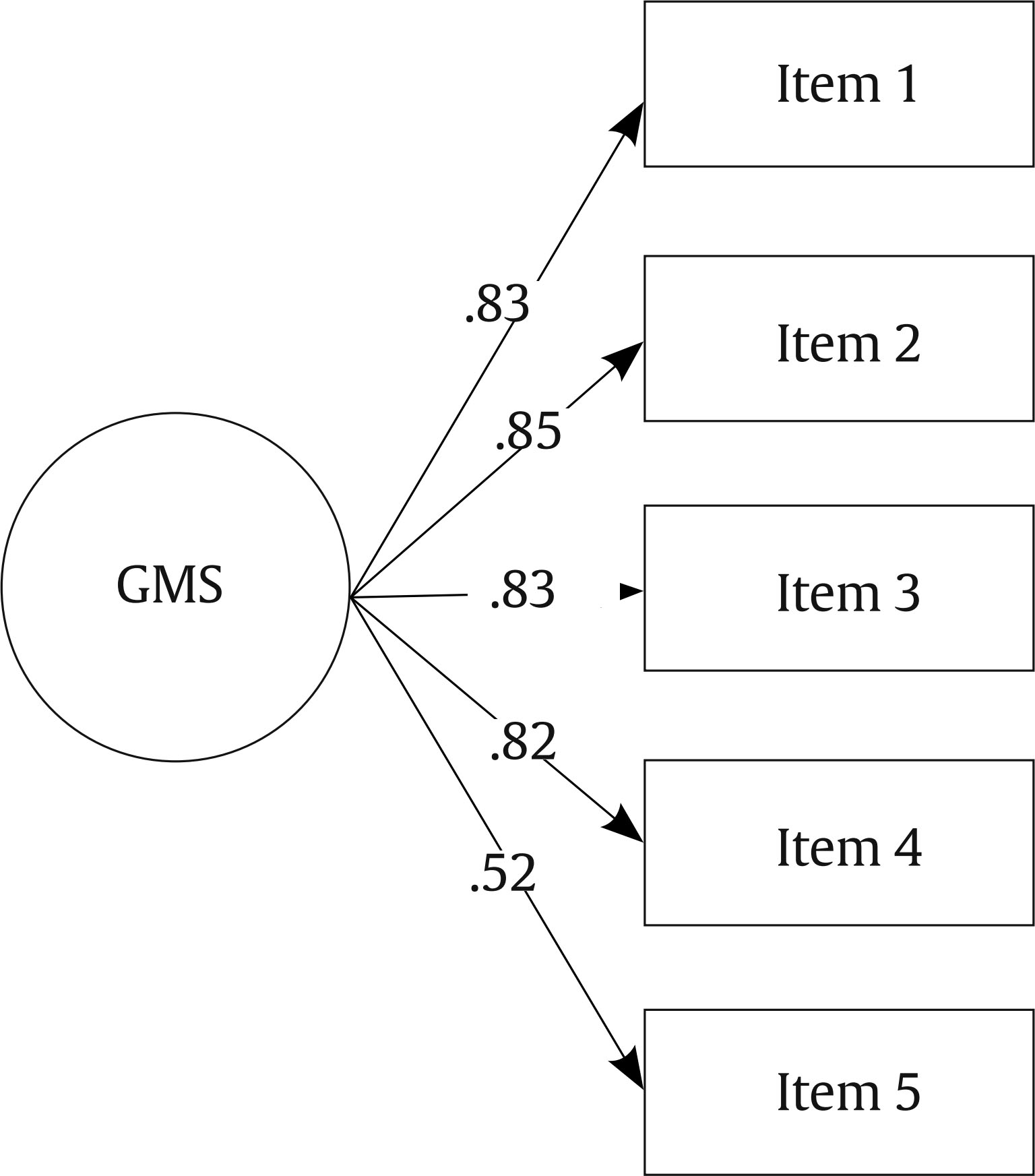

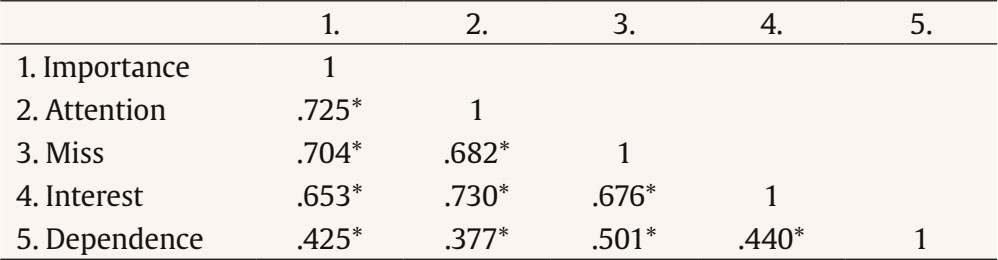

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis globally indicated that the unidimensional model presented an adequate fit to the data, χ2(5) = 40.556, p < .001; CFI = .976; RMSEA = .116, 90% IC [.084, .150], p < .001; SRMR = .029. Although a significant χ2 (p > .05) was found, which is very common in large samples (Marôco, 2010), the assessment of fit was based on the other indicators. The graphic representation of the model is presented in Figure 1. All factor loadings for the items were significant (p < .001), ranging from .52 to .85 (see Figure 1). Interitem correlations are presented in Table 2 and revealed medium to large effect sizes.

Reliability

Cronbach's alpha was .87 for the total score, which indicates a high internal consistency. All five items were significantly correlated with the GMS total score, and all corrected item-total correlations were above .30 (Field, 2009), as presented in Table 3, suggesting that all items represent the construct measured by the instrument. There were no significant increases in the alpha coefficient with the elimination of each item of the GMS, which is indicative of the contribution of all items to the scale reliability.

Convergent Validity

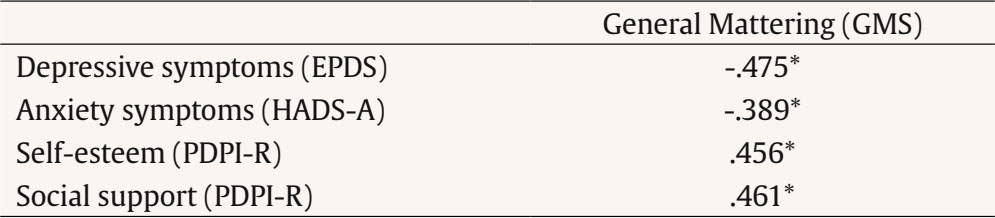

Correlations between general mattering and other variables were statistically significant (Table 4). General mattering was negatively correlated with postpartum depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. Therefore, women with higher perception of mattering to others had lower levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. On the other hand, the GMS was significant and positively associated with self-esteem and social support, meaning that participants with a higher perception of mattering to others also presented better self-esteem and satisfaction with the social support they received.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to adapt and validate the GMS to the Portuguese population and our findings provided evidence that the Portuguese version of the GMS is a reliable and adequate measure of mattering for postpartum women.

The results of this study showed that the distributional characteristics of the items were good. All answer options were selected at least eight times for each item. This reveals the diversity of our sample, since there were participants who identified negatively with the items (answering not at all or little) and other who identified positively with the phrases related to mattering (answering somewhat or very much). Furthermore, the one-factor structure of the Portuguese version of the GMS was confirmed, being consistent with previous research (Davis et al., 2019; Sari & Karaman, 2018). Our results also indicated that item 5 had a lower factor loading compared to the other items, which is in accordance with other findings reported in the literature (Connolly & Myers, 2003; Davis et al., 2019; Sari & Karaman, 2018). This result might be attributed to the nature of the item, since it refers to the perceived dependence of the others (i.e., "How much do you feel the people depend on you?"). It is possible that mothers can interpretate this item as being more related to responsibility that others' well-being or safety relies on one's actions than to mattering itself (Taylor & Turner, 2001).

The Portuguese version of the GMS also demonstrated to be a reliable measure of general mattering, presenting a high value of internal consistency (α = .87), which is aligned with the findings from other validation studies (e.g., Davis et al., 2019; DeForge & Barclay 1997; Stephen Lenz et al., 2018). Moreover, all items seem to represent the construct measured by the instrument and contribute to the high value of reliability of the GMS.

Concerning the correlations between the GMS and other instruments, mattering was negatively associated with depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms in our sample. These results are in is in line with previous studies with mothers in postpartum period (Caetano et al., 2022) and with other populations (e.g., Cha, 2016; Davis et al., 2019; Krygsman et al., 2022; Taylor & Turner, 2001). As previously mentioned, mattering is based on the perception that one is important and significant to others and to the community/society (DeForge & Barclay, 1997), which is important to promoting the individual's self-concept (Rosenberg & McCullough, 1981). In contrast, depression is based on a cognitive pattern based on a negative view of oneself, world, and the future (Beck, 1964). Thus, in this study, we can assume that mothers who had a low sense of mattering and perceived themselves as not significant to other people may present a negative view of themselves and a negative self-concept, which in turn can be associated to depressive symptoms. This is noteworthy as women express an increased need for support during the postpartum period, which is often unmet (Kanotra et al., 2007). It can be hypothesized that the perception of not being important to significant others when their needs are not being responded by their support network can be interpreted by women as a threat to their daily life, and then contribute to increased levels of anxiety. This association between mattering and anxiety symptoms has also been reported in other studies (Dixon et al., 2009) and this finding may be pertinent given the high prevalence and comorbidity of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the postpartum period (Radoš et al., 2018). In addition, and as expected (Davis et al., 2019; Flett & Nepon, 2020), mattering was positively correlated with self-esteem and social support. These constructs are particularly relevant for postpartum women since low self-esteem and lack of social support constitute risk factors for the development of postpartum depression (Alves et al., 2018). Consistently, women with lower levels of self-esteem and women who perceive support as unavailable may feel disconnected from significant others and may perceive that they are not important to them (Cha, 2016; Elliott et al., 2004).

This study adds important contributions to the literature, since it validates the GMS for a population of postpartum women that has been little explored in terms of mattering. This scale has good psychometric properties and is easy to administer due to it reduced number of items, which makes it appealing to use in research and in clinical practice, especially when several questionnaires are administered (Davis et al., 2019). The existence of an instrument of this nature may encourage more research on mattering in this population. Furthermore, the concept of mattering holds clinical relevance in both prevention and treatment psychological interventions for depressive and anxiety symptoms in the postpartum period. Future research should be focused on interventions designed to improve the perception of mattering in this sample. In fact, some interventions have been developed to increase levels of mattering, particularly among students (Flett et al., 2019). Also, it has been suggested that mattering can be applied in psychological assessment as an indicator of vulnerability, and within the therapeutic relationship itself, by verbally expressing empathy and recognition (Flett et al., 2019).

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design of the study did not allow the test-retest reliability of the GMS to be determined. Second, the construct validity was not assessed using another measure of mattering (e.g., The Mattering Scale; Elliott et al., 2004). Future studies should be conducted to provide additional evidence of test-retest reliability and construct validity. Third, the study sample was predominantly married, highly educated, and employed. Further research should assess the validity of the GMS among a more diverse sample, including other subgroups of the Portuguese population, in particular subgroups among men, to examine possible gender differences.

Conclusion

Mattering can play an important role in women's mental health during the postpartum period, but this construct has been little explored in this population. This paper contributes to important findings on the psychometric properties of the GMS in a sample of women during the postpartum period. Overall, the results of this study support the use of the Portuguese version of the GMS in both research and clinical practice by providing evidence that this is a unidimensional, reliable, and adequate instrument for measuring mattering among women in the postpartum period.