Introduction

Psychological problems continue to be among the top ten causes of disease burden worldwide (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022). Anxiety and depression disorders are among the leading causes of illness and disability among teenagers. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) reports that 1.1% of adolescents aged 10-14 years and 2.8% of those aged 15-19 years have experienced depression. Additionally, 3.6% of adolescents aged 10-14 years and 4.6% of those aged 15-19 years have experienced anxiety problems. In the review by Polanczyk et al. (2015), the global prevalence of mental health problems in children and adolescents was 6.5% (95% Confidence interval (CI) [4.7, 9.1]) for any anxiety disorder and 2.6% (95% CI [1.7, 3.9]) for any depressive disorder. To reduce the burden of mental health disorders, governments and institutions must provide coordinated, accessible, inclusive, timely, and universal mental health promotion and prevention strategies.

Anxiety and depression problems have a typical onset between the ages of 12 and 25 years (Uhlhaas et al., 2023), with the peak age of onset of mental disorders being 14.5 years (Solmi et al., 2022). At age 14, around 38% of youth in the general population have developed an anxiety disorder, and 3.1% have experienced a depressive disorder at least once in their lives (Solmi et al., 2022). Subthreshold depression and anxiety are also prevalent in adolescence. In addition, anxiety and depression symptoms during childhood and adolescence are associated with physical and mental health problems, as well as with a range of adverse outcomes including social relationships and educational impairments (Baker, 2021; Finning et al., 2019; García-Escalera et al., 2020; Quevedo-Blasco et al., 2023; Riglin et al., 2014; Veldman et al., 2015). Furthermore, undetected or untreated anxiety and depression symptoms have been linked to adverse outcomes on personal, familial, social, and academic functioning, as well as an increased risk of suicidal behaviors and psychopathology (Croarkin et al., 2018; Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez-Albéniz, 2020; Kroenke et al., 2009; Pérez-Albéniz et al., 2023; Thapar et al., 2022). Thus, failing to address adolescent mental health can have long-term effects on an individual's physical and well-being, as well as their ability to lead satisfying adult lives.

Sex and age are associated with the phenotypic expression of anxiety and depression symptoms and disorders. Research has shown a higher prevalence of both depressive and anxious symptoms in girls, with higher percentages at ages 13 and older (McLaughlin & Kevin King, 2015; Polanczyk et al., 2015; Thapar et al., 2022). For instance, previous studies have found that generalized anxiety symptoms varied by sex and age (Thompson et al., 2021). Specifically, women reported greater symptomatology than men, while younger participants reported higher levels than older participants. Studies by Canals-Sans et al. (2018) and Canals-Sans et al. (2019) found levels of anxious symptomatology that reached 8.7% for boys and 11.11% for girls between the ages of 10 and 14, and 17.8% for boys and 36% for girls between the ages of 15 and 19.

It is also important to consider the comorbidity between depressive and anxious symptomatology (Rapee, 2023; Sánchez Hernández et al., 2021; Thapar et al., 2022). In youth mental health, comorbidity between depression and anxiety is common. Previous research among adolescents has revealed that approximately 40% of those meeting the criteria for one class of mental disorder also meet the criteria for another class of lifetime mental disorder (Merikangas et al., 2010). Anxiety and depression symptoms and disorders might share common etiological factors. In this regard, prior studies have posited the presence of a general dimension of emotional dysregulation or internalizing problems. This perspective aligns with current transdiagnostic and psychopathology models (e.g., the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology, HITOP), wherein depression or anxiety are conceptualized as dimensional spectra distributed across a continuum (Eaton et al., 2023). From this broader framework, psychological distress should be mainly determined by the presence of emotional – or internalizing – symptoms such as anxiety and depression (Piqueras et al., 2021). These common overlaps lead, amongst other, to more difficult assessments, increased symptom severity, and complicated treatment methods.

The use of valid screening tools is relevant for a better understanding of these phenomena as well as for the early and reliable detection of youth with anxiety and depression symptoms for prevention purposes. Systematic screening for depression and anxiety has been recommended by major international associations (e.g., National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE, 2013]). Nonetheless, standardization in assessment and treatment has been lacking, particularly at early ages (Bernaras et al., 2019; Cucci et al., 2022). Identifying adolescents with symptoms of depression and anxiety in health, social, or educational settings can contribute to informed decision-making. In accordance with the guidelines outlined by the NICE (CG159), effective psychological interventions for addressing mental health issues exist. However, their accessibility to the entire population may be hindered by challenges in recognition attributed to the limited utilization of effective assessment tools (NICE, 2013).

Previous literature has identified numerous measurement instruments to assess symptoms of anxiety or depression, or more generally, the internalizing dimension, in adolescent populations (e.g., Bernaras et al., 2019; Creswell et al., 2020; Deighton et al., 2014; Piqueras et al., 2017; Spence, 2018). In this context, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 (GAD-7) are two widely employed measurement instruments that have shown adequate psychometric properties across samples (Arroll et al., 2010; Kroenke, 2021; Löwe et al., 2008; Mossman et al., 2017; Spitzer et al., 2006). The PHQ-9, developed by Kroenke et al. (2001), serves as a self-report instrument utilized for the assessment of depressive symptoms. Meanwhile, the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) is designed to evaluate generalized anxiety disorder. Previous studies have gathered sources of validity evidences, both adult and adolescent populations, including clinical and subclinical samples (Kiviruusu et al., 2023; Mossman et al., 2017). In the Spanish context, Fonseca-Pedrero, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Al-Halabí, et al. (2023) and Casares, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Lucas-Molina, et al. (2024) have respectively validated the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in large samples of adolescents. In addition, a brief version of both measures has been developed to assess depression and anxiety in educational contexts (Casares, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2024; Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2017).

To date, no previous studies have provided Spanish norms for the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 during adolescence. In this context, the main goal of this study was to provide Spanish normative data for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in a representative sample of Spanish adolescents in educational settings. The results will facilitate the adequate interpretation of individuals' raw scores to make informed and data-driven decisions. Reliable and valid assessment of mental health among young people is essential, as it enables early detection and identification of clinical and at-risk cases, which in turn may help to guide preventive interventions at a critical stage of human development such as adolescence.

Method

Participants

Stratified random sampling was conducted at the classroom level in the entire student population of La Rioja. The students attended various public and charter educational centers, including compulsory secondary education and vocational training. The strata were formed based on the ownership of the educational institutions, whether public or charter, and the educational level. A total of 34 schools and 98 classrooms participated in the study. Data were collected from October 2021 to February 2022.

The initial sample consisted of 2,640 students. Participants scoring above 2 on the Oviedo Infrequent Response Scale (n = 175) or aged 18 years and above (n = 247) were excluded from the sample. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 2,235 students, 1,045 males (46.8%), 1,183 females (52.9%), and 7 intersex (0.3%). The mean age was 14.49 years (SD = 1.76), with an age range from 12 to 18 years. The age distribution was as follows: 12 years, n = 280; 13 years, n = 387; 14 years, n = 396; 15 years, n = 408; 16 years, n = 371; 17 years, n = 240; and 18 years, n = 153. The majority of participants, 90.84%, identified themselves as Spanish.

Instruments

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001)

It is a self-report consisting of 9 items that assess depressive symptomatology based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Respondents answer the items based on the frequency of symptoms using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = some days, 2 = more than half of the days, 3 = almost every day). The validation of the PHQ-9 in Spanish adolescents adolescents was undertaken by Fonseca-Pedrero, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Al-Halabí, et al. (2023).

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006)

It is a self-report consisting of seven items with a 4-option Likert response scale (0 = never, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half of the days, and 3 = almost every day). It assesses the severity of symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder during the last two weeks. The GAD-7 has been validated in Spanish by Casares, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Lucas-Molina, et al. (2024).

The Oviedo Infrequency Scale-Revised (INF-OV-R; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019)

This was used to identify random, pseudorandom, or dishonest response patterns among participants. The INF-OV-R is a self-report questionnaire comprising 10 items with a dichotomous response format (yes/no). Students who answered more than two items incorrectly on the INF-OV-R were excluded from the sample.

Procedure

The research received approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of La Rioja (CEImLAR). Psychometric measures were administered to groups of 10 to 30 students using personal computers in a dedicated classroom during regular school hours. The administration was supervised by researchers trained in a standard protocol. No incentives were offered for participation. Families of the participants were requested to sign an informed consent form, granting permission for their children to participate in the study. Participants were briefed on the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of their involvement. This study is part of a broader project named Evidence-based Psychology in Educational Contexts (PSICE) (Fonseca-Pedrero, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Al-Halabí, et al., 2023; Fonseca-Pedrero, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Lucas-Molina, et al., 2023).

Data Analyses

First, descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were calculated for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 items, for the total sample, as well as for sex and age groups. Age groups were defined by separating the early pubertal or adolescent stage (ages 12 to 14) from the post-pubertal stage (ages 15 to 18) (WHO, 2021). Secondly, the presence of statistically significant differences according to sex and age groups was examined. For this purpose, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was carried out. Prior research has shown sex invariance in the PHQ-9 scores (Fonseca-Pedrero, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Al-Halabí, et al., 2023) and both sex and age invariance in the GAD-7 scores (Casares, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Lucas-Molina, et al., 2024). In the present study, data analysis revealed age invariance in the PHQ-9 scores. Subsequently, percentile rankings of the questionnaires were established for the overall sample and within groups categorized by sex and age. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 and JASP programs.

Results

Descriptive Statistics for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7

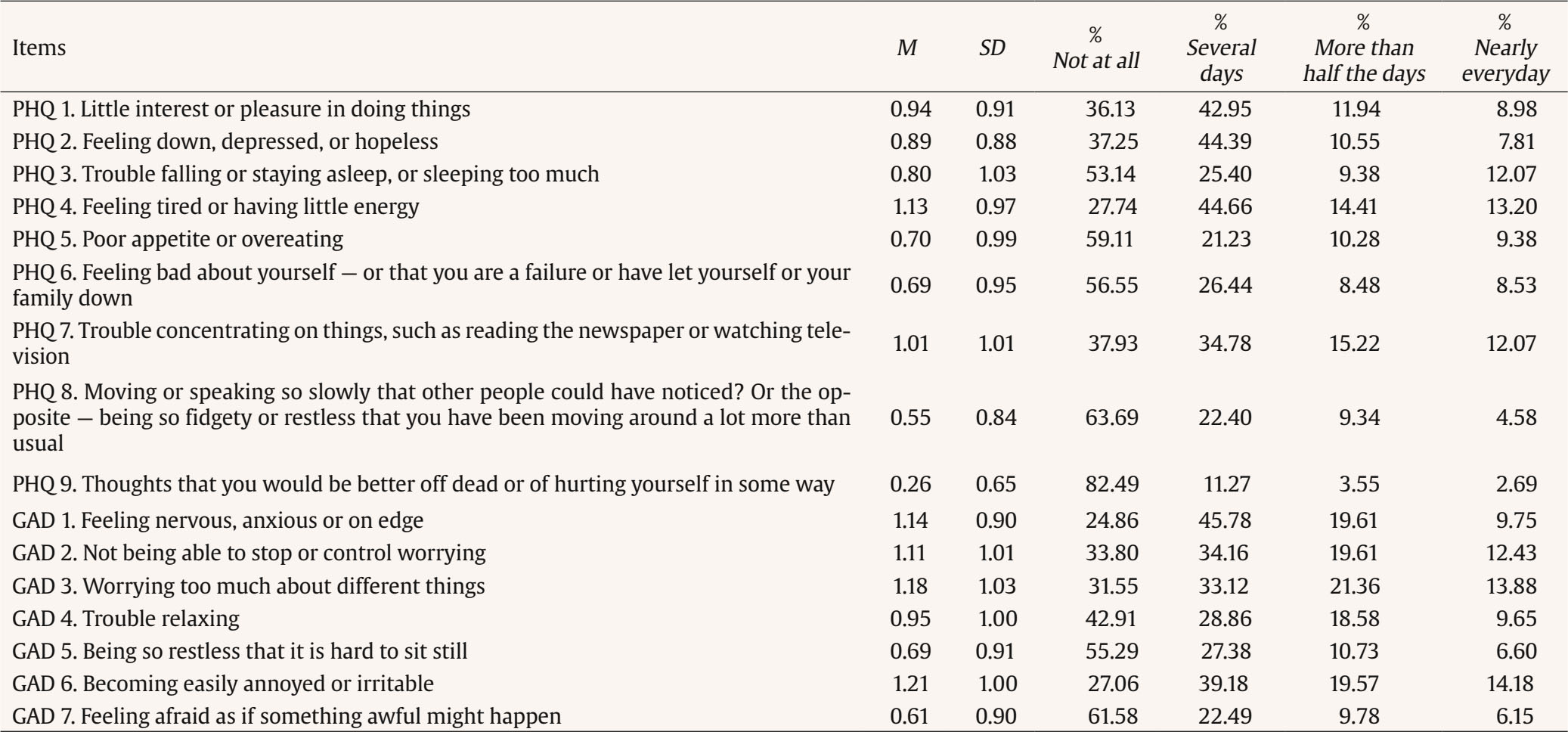

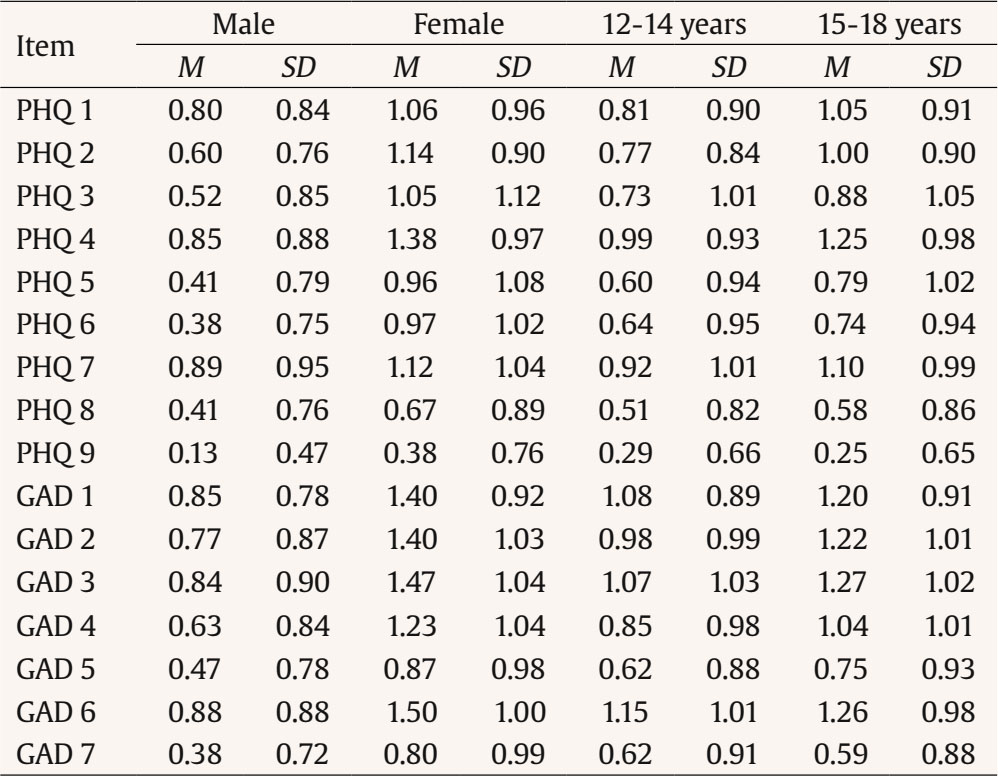

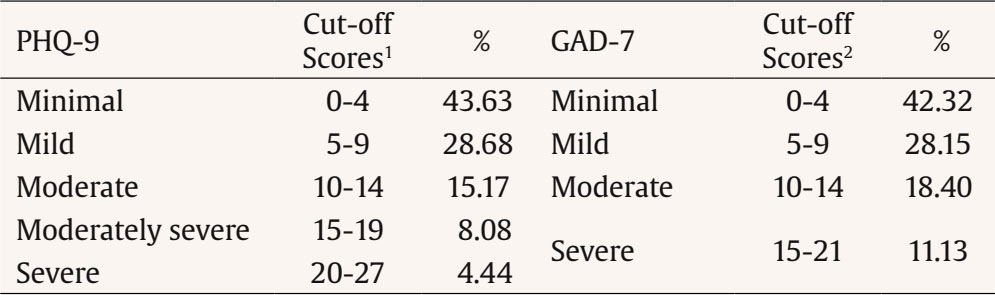

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 items. In Table 2, the descriptive statistics are delineated by sex and age group. The prevalence for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 according to the different levels of severity are presented in Table 3.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of the Items of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 (GAD-7) Based on Sex and Age

Table 3. Prevalence Estimates of PHQ-9 and GAD-7

Note

1Cut-off scores from Kroenke et al. (2001).

2Cut-off scores from Spitzer et al. (2006).

Comparisons of Mean PHQ-9 and GAD-7 Scores Based on Sex and Age

The MANOVA results confirmed statistically significant differences in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores based on participants' sex and age. Multivariate contrasts, analyzing mean score differences across both depression and anxiety scales, indicated significant differences associated with sex (λ = .859, F(1, 2233) = 181.74, p < .001; partial η2 = .14), and age (λ = 0.859, F(1,2233) = 181.74; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.14) and age (λ = 0.981, F(1,2233) = 21.94; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.019). However, the interaction between sex and age was not statistically significant (λ = 1, F(1, 2233)= 0.493, p > .05; partial η2 = 0).

Based on the sex of adolescents, univariate contrasts revealed that girls attained higher mean scores than boys, both in depression (λ = 1, F (1,2233) = 0.493; p > 0.05; partial η2 = 0); Mboys = 4.98, SDboys = 4.52; Mgirls = 8.74, SDgirls = 6.18, and in age (λ = 0.859, F(1,2233) = 181.74; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.14) and age (λ = 0.981, F(1,2233) = 21.94; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.019). Regarding the age of adolescents, univariate contrasts revealed that older adolescents (late adolescence) had higher mean scores than younger adolescents (early adolescence), both in depression (F(1,2224) = 43.67; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.019; Mearly = 6.25, SDearly = 5.64; Mlate = 7.64, SDlate = 5.83) and in anxiety (F(1,2224) = 26.67; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.012; Mearly = 6.38, SDearly = 5.17; Mlate = 7.32, SDlate = 5.36).

Normative Data for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in Spanish Adolescents

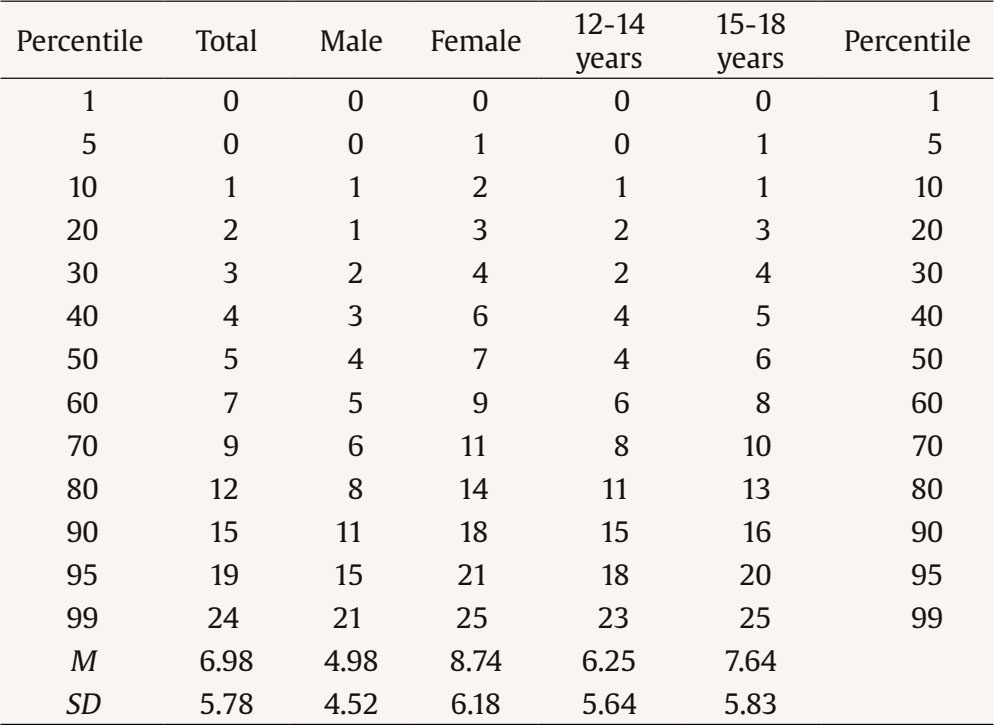

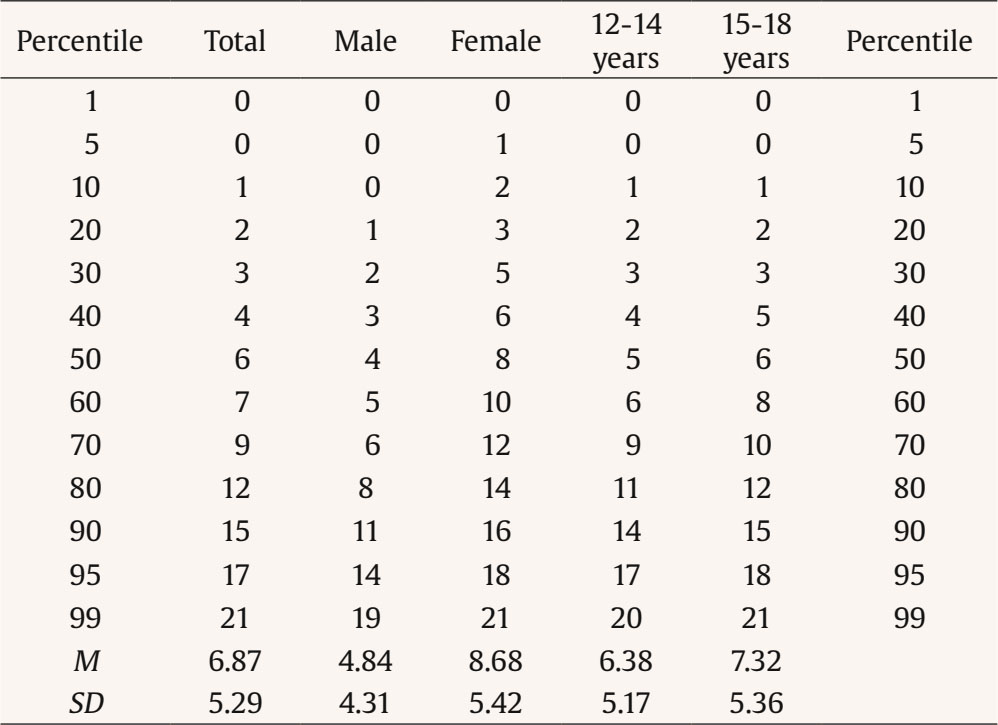

Based on the age and sex findings reported above, we calculated separate percentile ranks of raw values for two age groups, as well as for boys and girls. Tables 4 and 5 display percentile-type scaling for the scores on each questionnaire, both for the entire sample and by sex and age.

Discussion

Anxiety and depression symptoms and disorders during adolescence are distressing, impairing, and prevalent. They interfere with social relationships and educational achievement and increase the risk of suicidal behaviors and other mental health disorders. In addition, anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents are frequently misdiagnosed and undertreated. The assessment of emotional symptoms for epidemiological and preventive purposes is crucial. It is imperative that these tools are valid, useful, simple, and quickly administered within the child and adolescent population, as highlighted in previous research (Anum et al., 2019; Kiviruusu et al., 2023; Theuring et al., 2023). Thus, the aim of this study was to provide normative data of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 in Spanish adolescents.

The prevalence of severe anxiety symptomatology found in the analyzed sample reached 11.1%, while for depression symptoms were 4.44%. The results obtained in the present study seem consistent with previous international reports (Biswas et al., 2020; Canals et al., 2019; Shorey et al., 2022; WHO, 2021). For instance, Biswas et al. (2020) using a sample of 275,057 adolescents aged 12-17 years found that the overall 12-month prevalence of anxiety was 9.0%. Shorey et al. (2022) detected that the prevalence of major depressive disorder among adolescents was approximately 8% (95% CI [.02, .13]). In this study, moderate to severe depressive and anxious symptomatology were observed in 14% of boys and 38% of girls, and in 15% of boys and 41% of girls, respectively. Regarding age, adolescents aged 14 or younger exhibit rates of moderate to severe depressive and anxious symptomatology at 14% and 26%, respectively. In contrast, from the age of 15 onward, these figures rise to 31% and 33%, respectively. These results are consistent with recent research, such as the PSICE study (Fonseca-Pedrero, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Al-Halabí, et al., 2023). Previous studies with samples of Spanish adolescents (Canals-Sanz et al., 2018; Canals-Sanz et al., 2019; Casares, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2024; Dooley et al., 2023; Plenty et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2021) have shown that girls exhibit higher levels of depressive and anxious symptomatology compared to boys, and older adolescents exhibit higher levels than younger ones. These variations in the phenotype expression of internalizing symptoms may be related to a developmental period that involves physical, psychological, and social changes, which may increase an individual's sensitivity and reactivity to stress exposure.

A reliable and early detection of anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents is one of the main strategies for their prevention. To screening purposes it is necessary to have measurement instruments with appropriate psychometric properties. These measuring instruments allow for the assessment of the mental health status of individuals, including minors. For adolescents, it is recommended to use simple and brief items that are easily understandable. These are the reasons that have led to the administration of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, freely available instruments capable of assessing the presence of self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. These tools have shown evidence of validity and adequate reliability scores in Spanish adolescents (Casares, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2024; Casares, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Lucas-Molina, et al., 2024; Fonseca-Pedrero, Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Al-Halabí, et al., 2023). Furthermore, a reliable and valid assessment of mental health in young people is crucial as it allows for the detection and early identification of adolescents at high risk. This, in turn, can support rapid referral and provide better guidance for psychological treatment during a critical stage of human development, such as adolescence (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2021). The establishment of scoring criteria for the total sample and the subgroups formed based on sex and age provides the opportunity to interpret the scores by considering the reference group. Additionally, these criteria, derived from the scores observed in a representative sample of the adolescent population in Spain, are highly beneficial for evaluating, diagnosing, and addressing depression and anxiety symptoms in boys and girls aged between 12 and 18 years of age.

The simultaneous presence of symptoms related to various mental health issues implies the necessity of assessment and diagnostic procedures that consider this overlap. Comorbidity is frequently observed, particularly concerning depressive and anxious symptoms. Meta-analyses conducted by Avenevoli et al. (2001), Garber and Weersing (2010), and Yorbik et al. (2004) suggest that, on average, between 15% and 75% of young individuals with depressive symptoms also exhibit symptoms of anxiety. Furthermore, approximately 10% to 15% of young people diagnosed with an anxiety disorder have received a concurrent diagnosis of comorbid depressive disorder at some point in their lives. Other population-based epidemiological studies have similarly documented a high comorbidity among internalizing disorders (Kessler et al., 2012; Merikangas et al., 2010). This comorbidity associated with the internalizing dimension not only contributes to the understanding of existing psychopathology but also sheds light on potential vulnerability, as risk and protective factors across various levels (Hanking et al., 2016).

Hankin et al. (2016) highlighted the utility of dimensional models in comprehending the co-occurrence of various types of internalizing psychopathology symptoms. In addition, transdiagnostic models are used to explain the high prevalence of comorbidity between disorders. Cognitive vulnerabilities and risk factors, such as executive function or information processing biases, can predict both a single internalizing dimension and specific symptoms. Moreover, the process of maturation during childhood and adolescence integrates biological, cognitive, affective, and social systems, giving rise to risk or protective mechanisms.

It is necessary to implement programs for the promotion of mental health and the prevention of emotional problems in school settings. This can be accomplished through the implementation of reliable screening systems. Universal school-based screening would improve the detection of adolescent depression and anxiety and reduce the limited capacity of the healthcare system to provide adequate psychological support to those who clearly need treatment. In this context, compared to other methods (e.g., clinical interviews), the use of self-reports constitutes a rapid, efficient and non-invasive method of assessment. Depression and anxiety screening and prevention programs for young people need to go beyond the clinic walls. The overarching goal is to diminish the likelihood of future disorders and mitigate the health burden across various levels, including the personal, family, school, and societal spheres. Furthermore, investing in preventive strategies has the potential to enhance the psychological well-being of children and society as a whole, as emphasized in prior studies (Beardslee et al., 2013; Solmi et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023).

Certain limitations of the present study need consideration. Firstly, the data collection instruments employed are self-reports, introducing potential concerns related to social desirability and introspective capacity, particularly when assessing a sample of adolescents. Additionally, it is essential to acknowledge that the norms calculated in this study are derived from adolescents attending schools in the same Spanish region (La Rioja). Therefore, caution should be exercised when attempting to generalize the obtained results.

This study validates the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores for use in Spanish adolescents and provides normative data based on sex and age to ensure appropriate interpretation of tests scores. The PHQ-7 and GAD-7 may be used as screening tools for the universal early detection of depression and anxiety symptoms during adolescence in clinical and school settings. Future research could replicate these findings in samples of adolescents from various Spanish regions, engage in longitudinal studies, incorporate assessment methods based on information technology (Elosua et al., 2023), or explore the relationship between depressive and anxious symptoms with other bio-psycho-social variables and risk and protective factors (Álvarez-Marín et al., 2022; Cuijpers et al., 2023; Ortuño-Sierra et al., 2022). Furthermore, it is crucial to determine the cut-off points and compare them with those obtained from diverse populations. Finally, validated and standardized tests could be included on a national platform of freely available Spanish-language tests, as part of a comprehensive strategy for open science in the field of psychology.