Introduction

Despite the advancement in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) rights in certain regions of the world, individuals with diverse sexual orientation and gender identities continue to face victimization, exclusion, and discrimination from friends, family, coworkers, and society (Balsam et al., 2013; World Health Organization, 2015). The minority stress framework, first proposed by Brooks (1981) and then expanded by Meyer (2003), suggests that LGBTQ+ people face daily distal and proximal minority stressors associated with their social identities and statuses. These minority stressors extend beyond the general stress experienced by cisgender heterosexual individuals. According to prior research, people with multiple intersecting marginalized identities may be at a higher risk of exposure to discrimination and minority stressors, and related mental health challenges. Notably, most of the studies on minority stress have focused on individuals from the United States and Canada (Charak et al., 2019; Dürrbaum & Sattler, 2020; Pellicane & Ciesla, 2021), with a lesser number of studies focusing on minority stressors outside of the U.S./Canada across culturally and ethnically diverse populations (Sattler & Lemke, 2019). Given the pervasiveness and complexity of the problem, it is crucial to direct efforts towards the development of minority stress measurement tools and research to achieve a better understanding of the phenomena across different cultures and regions.

Minority Stress and Health

As mentioned, the minority stress framework proposes that individuals may experience two types of stressors, namely distal and proximal stressors. Distal minority stressors (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003) encompass external events of harassment and discrimination towards sexual and gender minority groups (e.g., heterosexist discrimination, vicarious trauma, or rejection by the family). Proximal stressors involve negative beliefs and attitudes towards one's gender or sexual identity (e.g., internalized homophobia, concealment, and stigma consciousness; Meyer, 2003). Research on minority stressors has indicated that distal and proximal stressors are correlated, suggesting a bidirectional association, wherein distal stressors could contribute to higher levels of proximal stressors and vice versa (Douglass & Conlin, 2020). For example, experiences of harassment (distal stressor) could increase stigma consciousness (proximal stressor), while the anticipation that an external stressor will occur (proximal stressor) could at the same time increase discrimination experiences by increasing emotional and behavioral reactivity in anticipation of being a target of prejudice (Valentine & Shipherd, 2018). Therefore, examining distal and proximal stressors is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between minority stressors and related mental health challenges (Schmitz et al., 2020).

A growing body of research on LGBTQ+ minority stressors has highlighted that the widespread prejudice and discrimination experiences may explain the mental and physical health disparities among LGBTQ+ individuals when compared to cisgendered heterosexual individuals. Furthermore, studies indicate that within the LGBTQ+ community there is also prejudice and microaggression, often directed towards transgender, gender diverse, and bisexual individuals, which can create within-group disparities in health among LGBTQ+ individuals (Balsam et al., 2013; Douglass & Conlin, 2020; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003). Overall, prior studies suggest that higher levels of prejudice and perceived experiences of discrimination are related to higher levels of physical health problems, such as sleep difficulties, headaches, strong aches, and pain (Denton et al., 2014). Studies also suggest that prolonged internalized stigma, microaggressions, and victimization experiences could be associated with alcohol and marijuana use (Trujillo et al., 2020; Villarreal et al., 2021). Additionally, stigma and LGBTQ+ identity disclosure have been associated with greater levels of depression among gay and bisexual men (Pachankis et al., 2019; Talley & Bettencourt, 2011). Furthermore, internalized homophobia, isolation, and discrimination have been related to lifetime suicidal ideation (Kittiteerasack et al., 2021; Meyer et al., 2021). Finally, higher levels of harassment and rejection by one's family of origin have been related to bidirectional face-to-face and cyber intimate partner violence patterns among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults (Ronzón-Tirado et al., 2021).

Special attention should be paid to the prior documented relation between heterosexist experiences and mental health problems (e.g., depression, suicidal ideation; Kittiteerasack et al., 2021; Meyer et al., 2021; Pachankis et al., 2019; Talley & Bettencourt, 2011), as well as how belonging to diverse social oppressed statuses could increase the risk of exposure to minority stressors. For instance, bisexual men and women have been proven to be at a greater risk of proximal stressors, such as isolation, while gay men and lesbian women are at a greater risk of exposure to distal minority stressors, such as discrimination and rejection (Mereish et al., 2017). Moreover, higher levels of discrimination and distress have been found in transgender and gender diverse individuals (TGD) when compared with cisgender LGB and heterosexual individuals (Kattari et al., 2020; Su et al., 2016; Valentine & Shipherd, 2018; Wiepjes et al., 2020). Additionally, lower levels of discrimination and victimization seem to be common among urban LGBTQ+ individuals when compared to those from suburban and rural backgrounds (Morandini et al., 2015; Shramko et al., 2018). Acknowledging these differences in prevalence rates, understanding the role of multiple marginalization, and related experiences of distress could potentially help in the implementation of a more informed clinical interventions and social justice and advocacy programs to address this pervasive problem.

The Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire

It is important to emphasize that the findings regarding minority stressors among LGBTQ+ individuals from Spain are still at a nascent stage. Furthermore, the limited availability of standardized tools/instruments to address the consequences of these stressors makes challenging to contrast findings across studies (McConnell et al., 2018; Mijas & Koziara, 2020; Shramko et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2020). Among the currently existing heterosexism measurement scales, the Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire (DHEQ; Balsam et al., 2013) is a widely used measure of minority stressors. The DHEQ has shown to be a statistically and theoretically interesting choice for researchers when examining issues of discrimination based on an individual's sexual and gender identities. Specifically, the DHEQ factors comprise distal and proximal minority stressors facilitating the analysis of health disparities among LGBTQ+ people. In this sense, the DHEQ allows exploring the prevalence and distress caused by each minority stressor. Among the included distal factors, the scale comprises daily heterosexist experiences of ill-treatment, verbal abuse, and physical abuse, such as discrimination/harassment, rejection from the family of origin, the ostracism related to one's own gender expression, and exposure to vicarious trauma. Among the proximal factors, the scale includes vigilance and isolation, consisting of actions aimed to conceal one's sexual/gender identity, difficulties to establish contact with other LGBTQ+ people, and a feeling of loneliness.

Regarding the psychometric characteristics of the scale, the DHEQ items measure the domains with a Likert-type scale that gathers information about how much each problem has bothered an individual during the last 12 months (from 0 = did not happen/not applicable to me to 5 = it happened, and it bothered me extremely). The response categories were designed to allow for two ways to compute scores for the subscales of the DHEQ. First, the distress dimension score can be created by computing the mean of the responses. Alternatively, the number of experiences that the person reports for each dimension/subscale can be scored by counting how many items did the participant experience (Balsam et al., 2013). So far, the reliability and internal consistency of the DHEQ dimensions have been tested in individuals from the United States and Poland, with findings indicating adequate psychometric properties (Balsam et al., 2013; Mijas & Koziara, 2020). Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, this measure has not been adapted and validated in a Spanish-speaking sample. Therefore, is crucial to adapt and validate the DHEQ in other languages and to test the validity assessments of the DHEQ across samples from different nations and cultures.

The Current Study

The present study had three aims. First, to examine the factor structure of a popular measurement tool, namely the Daily Hetero-sexist Experiences Questionnaire (DHEQ), that assessed daily heterosexist experiences through six subscales (out of the nine subscales) among Spanish-speaking adults living in Spain. These six dimensions were selected as they are the most frequently used in the existing literature on minority stressors, and these six dimensions have proven to be reliable when capturing heterosexist experiences of both, cis-and trans-LGBQ+ individuals (Landes et al., 2021; Tucker et al., 2019; Vencill et al., 2018). Furthermore, these six dimensions are not exclusive to specific stressors of the LGBTQ+ population, such as the HIV or the parenting dimensions which are intended only for people with HIV positive status or those with children, respectively. In addition, the predictive validity of the scale was tested by comparing the DHEQ scores with depression (via the Patients Health Questionnaire 9; PQH-9: Spitzer et al., 1999), and suicidal behavior scores (via the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised; SBQ-R: Osman et al., 2001). Second, the present study aimed to explore the rates of distal and proximal heterosexist experiences among Spanish adults and investigate the differences across gender and sexual identities, immigration status, and urban versus rural residence. Third, this study also sought to examine the predictive value of the DHEQ rates on two mental and behavioral health outcomes, depression and suicidal behavior, after adjusting for identities (e.g., gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and urban-rural residents). It was hypothesized that: 1) the DHEQ would demonstrate its prior documented psychometric strengths (Balsam et al., 2013; Mijas & Kosiara, 2020) for measuring heterosexist experiences among LGBTQ+ adults from Spain; 2) the rate of exposure to heterosexist experiences would vary across social identities, with marginalized identities, such as TGD individuals, those identifying as bisexuals, non-Caucasian individuals, and people residing in rural areas reporting higher levels of mental health outcomes as a consequence of their heterosexist experiences (Tan et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020); 3) higher risks of depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior would be associated with a greater exposure to distal (e.g., discrimination/harassment) and proximal (e.g., vigilance) heterosexist experiences, and individuals with diverse social oppressed statuses (e.g., TGD individuals, racial minority groups) would experience higher levels of minority stress and mental health consequences (Kattari et al., 2020; Su et al., 2016; Wiepjes et al., 2020).

Method

Participants

Participant were 509 LGBTQ+ identifying adults in the age range of 18 to 60 years old (M = 29.70, SD = 9.03) from different regions of Spain, including urban (83%, n = 421) and rural (17%, n = 86) areas. Nearly 86.2% (n = 436) identified themselves as Caucasian/White, 7.5% (n = 48) as Latinx, and 6.4% as other/multiracial (n = 32). Most of the participants identified as cisgender (women: 33.3%, n = 166; men: 43.0 %, n = 214) and to a lesser extent as transgender/gender diverse (woman: 2.6%, n = 13; man: 8.4%, n = 42; and non-binary/other: 12.6%, n = 63). Participants identified their sexual orientation as lesbian (12.4 %, n = 63), gay (39.6 %, n = 188), bisexual (39.5%, n = 201), heterosexual (3.9 %, n = 20), asexual (2.7%, n = 14), pansexual (2.3%, n = 12), demisexual (0.78%, n = 4), and queer (0.59 %, n = 3). Nearly 17.9% (n = 91) indicated that their highest level of education was high school or less, 33.8% (n = 81) indicated having an associate degree or having attended/graduated some college courses, 34.4% (n = 175) indicated having a Bachelors' degree, and 31.8% (n = 162) had a postgraduate or advance degree. About 14.2% (n = 72) were unemployed, 35.7% (n = 181) reported having a job, 32.5% were full time students (n = 165), and the remaining 17.4% (n = 88) reported to be currently working and studying at the same time.

Measures

Heterosexist Experiences

The Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire (DHEQ; Balsam et al., 2013) is a 50-item measure that assesses the unique aspects of minority stress for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults across nine domains, namely gender expression, vigilance, parenting, discrimination and harassment, vicarious trauma, family of origin, HIV/AIDS, victimization, and isolation. Each item is measured on a six-point Likert-scale indicating the presence/absence of the stressor and the impact on the individual (0 = did not happen/not applicable to me, or it happened, 1 = it bothered me not at all, 2 = it bothered me a little bit, 3 = it bothered me moderately, 4 = it bothered me quite a bit, and 5 = it bothered me extremely). For the purpose of the present study, six subscales were translated and back-translated by two bilingual speakers (English-Spanish) with their native language being Spanish and a posteriori check for discrepancies by a third bilingual researcher following internationally accepted practices for the translation and validation of measurement scales (Gjersing, et al, 2010).

Depression

The Patients Health Questionnaire-9 (PQH-9; Spitzer et al., 1999) is a 9-item module from the full PHQ which scores each of the nine Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria for depression. It is a Likert-type scale with 4 response options: 0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, and 3 = nearly every day. As a severity measure, the PHQ-9 score can range from 0 to 27, where higher scores represent higher levels of depression experienced by the person in the last two weeks. The original version of the measure demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (α = .89; Spitzer et al., 1999), and good criterion validity (r = .84; Spitzer et al., 1999). The PHQ-9 has been validated in clinical and non-clinical samples from Spain (Marcos-Nájera et al., 2018; Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2017; Pinto-Meza et al., 2005) showing good internal consistency and convergent validity. A cutoff score of 10 or greater indicates major depression disorder in samples from Spain and has 84% sensitivity and 92% specificity. In the present study, the PQH-9 had good reliability data with Cronbach's alpha coefficients equivalent to .91 (95% CI [.90, .92]).

Suicidal Behavior

The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001) Spanish form (SBQ-R; Gómez-Romero et al., 2019) comprises four items that measure different dimensions of suicidality. Item 1 assesses lifetime suicide ideation and attempt, item 2 the frequency of suicidal ideation over the last 12 months, item 3 the threat of suicidal behavior, and item 4 evaluates the self-reported likelihood of suicidal behavior. The four items can be summed for a total score ranging from a minimum of 0 (no suicidal ideas or behaviors) to a maximum of 18. The original SBQ-R showed good of internal consistency (α = .76-.87) and test-retest reliability at two weeks (r = .95; Osman et al., 2001). The Spanish version showed as well good internal consistency (α = .81) and test-retest reliability (r = .88; Gómez-Romero et al., 2019). Additionally, they found that the SBQ-R showed good criterion validity when correlated with other scales (i.e., suicide risk, self-stem; Gómez-Romero et al., 2019). According to the authors of the Spanish version, a score equal to or higher than 6 indicates a suicide risk with 93% of sensitivity and 95% of specificity. In the present study, the SBQ-R obtained good reliability data with Cronbach's alpha coefficients equivalent to .82 (95% CI [.79, .85]).

Procedure

First, two bilingual (English-Spanish) graduate-level researchers, one from Spain and one from México, independently translated the DHEQ to Spanish. They focused on grammar, terminology, and the colloquial use of words of Latinx and Spaniard populations to ensure that the translation process considered the cultural, psychological, and linguistic differences in both cultures. While there was an agreement between the Mexican and the Spaniard researcher about the colloquial terms used to call gay, bisexual, and gender diverse man marica/maricón, researchers had to discuss the colloquial terms to refer to lesbian women or women who did not comply with hetero-normative gender roles. Such terms were less obvious and inconsistent between the two countries. Then a third bilingual researcher from the United States carried out the backtranslations of the scale to ensure the maintenance of the semantic equivalence. Any discrepancies between the researchers were discussed until an agreement was reached. Participants were recruited through social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram), and the study was advertised as Experiencias heterosexistas, relaciones interpersonales y salud mental en población LGBTQ+ adulta (English translation: Heterosexist experiences, interpersonal relationships, and mental health in LGBTQ+ adults). To recruit participants for the survey, LGBTQ+ associations and LGBTQ+ influencers from Spain were contacted to request their collaboration by posting the study link and flyers for the survey in their online profiles. The survey was available online from March to May 2021. Inclusion criteria were (a) identifying as a Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer and Two-Spirit (LGBTQ2S+) person, (b) residing in Spain, and (c) being 18 years or older. Informed consent was obtained from each participant at the beginning of the survey when they were also notified about confidentiality and the option to leave the study anytime without any penalty. Participants completed the online questionnaire via Qualtrics platform which included questions on demographics, minority stressors, and mental health outcomes. Multiple attention check questions (e.g., "If you are reading this item, check option 2") for checking response validity were included and individuals who failed even one attention check item were removed from the final analyses (n = 5, 0.97%). Survey completion took an estimated 35-50 minutes. All the procedures in the study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Madrid under the code CEI 114- 2262.

Data Analyses

The descriptive statistics and departure from the normality were tested for each of the study variables using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality. The sample did not follow a normal distribution of data since all the variables follow a probability less than or equal to .05. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was tested for the DHEQ using the estimator weighted least squares mean-variance adjusted (WLMSV), since it has proven to be a robust estimator when using ordinal scales as in the DHEQ and it offers the best statistical guarantee by estimating a weight matrix based on the asymptotic variances and covariances of polychoric correlations and assuming a latent normal distribution underlying each categorical variable observed (Byrne, 2012; Flora & Curran, 2004). To study model fit, the following goodnes-of-fit indices were considered (Jöreskog, 2001): comparative fit index (CFI; acceptable fit = CFI ≥ .90), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; acceptable fit = TLI ≥ .90), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; acceptable fit .05 ≤ RMSEA ≤ .08) (Jöreskog, 2001). Then, internal consistency of the DHEQ dimensions was tested using Cronbach's alpha and omega statistics. Next, to test the construct validity of the DHEQ, Welch T tests were performed to assess differences between known groups by gender identity (cisgender vs. TGD individuals), sexual orientation (gay/lesbian vs. bisexual/pansexual/asexual/demisexual/queer), and race (Caucasian-Anglo-Saxon vs. Latinx/Asian/African/multiracial). The categorization of the sexual orientations aimed to a) examine the greater documented physical and mental health challenges faced by emergent and less visible sexual orientations (i.e., bisexual, demisexual, pansexual, and queer) compared to lesbian and gay individuals (Borgogna et al., 2019; Smalley et al., 2016) and b) to guarantee the statistical power of the analyses, especially in relation to sexual orientations whose sample size was less than 3% of the total sample. Spearman correlations were used to test associations between the six dimensions of the DHEQ, and depression and suicidal behavior. Finally, logistic regression models were tested to examine the predictive value of exposure to the six types of heterosexist experiences, gender identity, sexual orientation, and race over depression and suicidal behavior. The CFA was performed using Mplus version 7 and the remaining analyses were performed in SPSS version 25.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

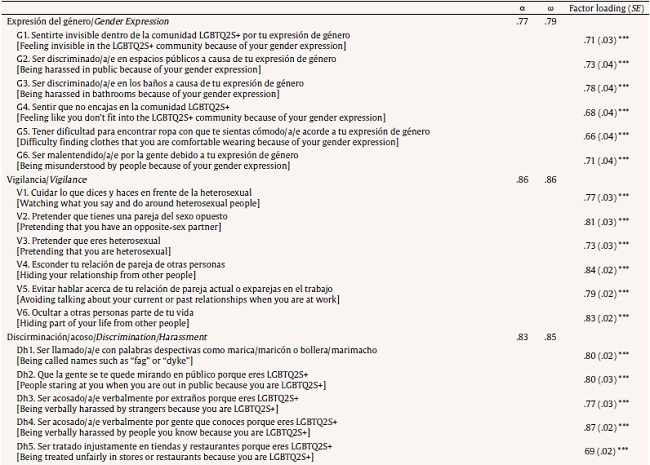

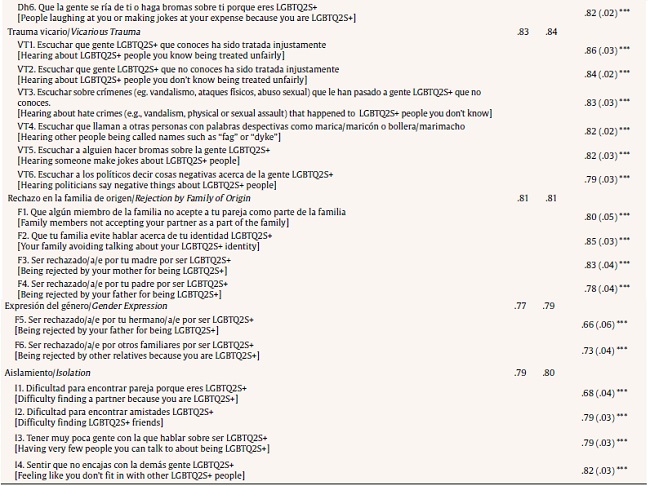

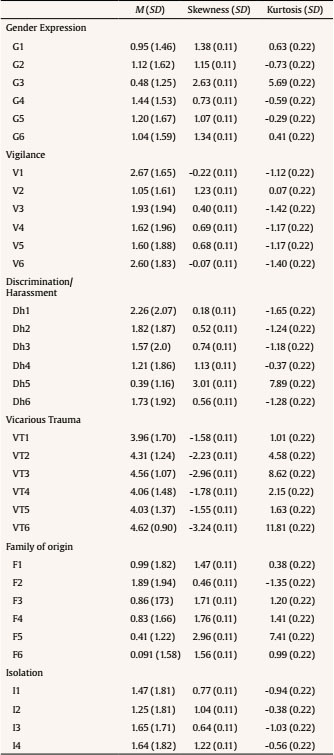

Confirmatory factor analyses supported the six-factor structure, one for each minority stress dimension from the DHEQ (i.e., gender expression related harassment, vigilance, discrimination/harassment, vicarious trauma, rejection by the family of origin and isolation; Balsam et. al., 2013; see Table 1 for the Spanish items of the DHEQ). CFA showed an acceptable level of goodness-of-fit indices (CFI = .912, TLI = .904, RMSEA = .064 [.061, .068]), and all items had indices over the acceptable range (factor loading < .60, R2 < .30; Hooper et al., 2008; Table 1). The reliability for each dimension was tested through the Cronbach's alpha and omega coefficients, and findings demonstrated a good internal consistency for each subscale (i.e., gender expression related harassment: α = .77, 95% CI [.76, .81], ω = .79; vigilance: α = .86, 95% CI [.84, .88], ω = .86; discrimination/harassment: α = .83, 95% CI [.81, .86], ω = .85; vicarious trauma: α = .83, 95% CI [.81, .85], ω = .84; rejection by family of origin: α = .80, 95% CI [.77, .83], ω = .81; and isolation: α = .79, 95% CI [.75, .81], ω = .80). Omega total for the scale was ωu = .91. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the DHEQ items.

Predictive Validity: Differential Experiences across Identities

Welch T test allowed to assess the ability of the DHEQ to screen differences between known groups. Findings revealed that marginalized identities, namely TGD, were exposed to more minority stressors. TGD individuals including, transmen, transwomen, and non-binary individuals, when compared to cisgender LGBQ individuals, were exposed to greater experiences of discrimination and harassment, t(172,916) = -4.285, p < .001, heterosexism related to their gender expression, t(138,693) = -15.77, p < .001, rejection by the family of origin, t(156,147) = -5.49, p < .001, and isolation, t(172,018) = -3.67, p < .001. Sexual orientations, namely, asexual, pansexual, demisexual, and bisexual identities were exposed to higher experiences of discrimination and harassment, t((509,932) = 3.28, p < .001, heterosexism related to their gender expression, t(472,369) = -4.12, p < .001, and vicarious trauma, t(500,875) = -3.25, p < .01. Furthermore, individuals who self-identified as either Latinx, Asian, African, or multicultural (i.e., non-Caucasian or non-Anglosaxon) reported greater experiences of harassment related to gender expression, t(91,702) = 2.14, p < .001, and vicarious trauma (t = -2.25, p < .05). No differences were found for the prevalence of heterosexist experiences between LGBTQ+ individual who lived in rural versus urban areas.

Criterion Validity

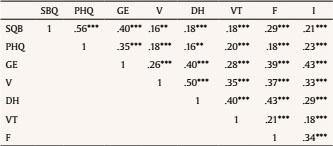

Criterion validity was tested by analyzing the ability of the scale to assess associations between exposure to minority stressors and mental health outcomes. Spearman correlations indicated low-to-moderate levels of associations between the six dimensions of the DHEQ, depression, and suicidal behavior total scores (rrange = .16 to .35; Table 3).

Rates of Minority Stressors and Mental Health Outcomes among LGBTQ+ Adults

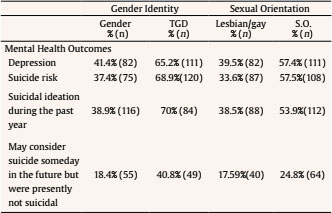

Findings revealed that nearly all participants have been exposed to at least one heterosexist experience during the past one year. Vicarious trauma showed to be the most frequent stressor (99.8%, n = 508) followed by vigilance (93.8%, n = 508), discrimination/harassment (84.2%, n = 506), and isolation (81.7%, n = 508). Regarding mental health outcomes, nearly half of the participants met the cutoff criteria of depressive symptoms (47.4%, n = 195) and suicidal behavior (46.1%, n = 193; Table 4). Additionally, 77.3% (n = 326) of the participants either had suicidal ideation or had attempted suicide at least once in their lives and 47.3% (n = 200) had suicidal ideation during the past year. Nearly 42% (n = 175) of the participants had told someone that they were going to commit suicide during their lives and 24.8% (n = 104) said that they may consider suicide someday but were presently not suicidal. Prevalence rates for clinical depression and suicidal ideation among gender identities and sexual orientations are described in Table 5.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables: Prevalences, Means, and Standard Deviations.

Note.1percentage of participants that experiences at least one situation for each DHEQ dimension; 2percentage of participants that met the cut criteria for that specific mental disorder.

Table 5. Mental Health Outcomes Prevalence Rates by Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation.

Note.Table shows percentage of participants that met the cut criteria for each mental health outcome. S.O. = sexual orientation other than heterosexual, lesbian or gay (i.e., bisexual, pansexual, demisexual, queer, asexual).

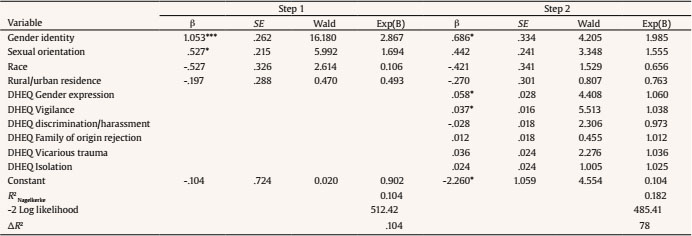

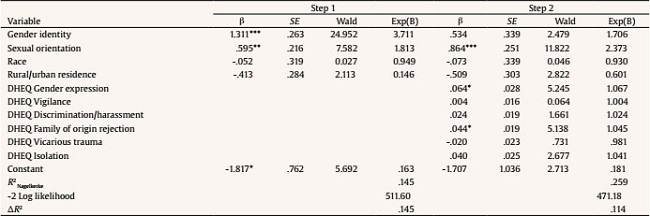

Minority Stressors and Mental Health Outcomes among LGBTQ+ Adults

The models examining the cumulative effect of the six types of daily heterosexist experiences on symptoms of depression and suicidal behavior after controlling for covariates (i.e., gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and rural/urban residence) were significant. When analyzing the risk of depression as an outcome, results showed that identifying as a TGD individual, having a minority sexual orientation (bisexual, asexual, pansexual, or identities other than gay or lesbian; step 1), and higher scores on heterosexism related to their gender expression and vigilance (step 2) increased the risk for depression (Table 6). Furthermore, when analyzing the risk for suicidal behavior (Table 7), results showed that identifying as a TGD individual, having a minority sexual orientation (bisexual, asexual, pansexual, or identities other than gay or lesbian; step 1), and higher scores on heterosexism related to their gender expression, and rejection from the family of origin (step 2) increased suicidal risk.

Table 6. Hierarchical Logistic Regression Models Predicting Depression on DHEQ After Controlling for Identity Covariates.

Note.Gender identity (cis = 0 vs. transgender = 1); sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, or heterosexual = 1 vs. others = 0); race (Caucasian-Anglosaxon/White = 0 vs. others = 1); rurality (rural = 0 vs. urban = 1); DHEQ = Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire.

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

Table 7. Hierarchical Logistic Regression Models Predicting Suicide Risk on DHEQ After Controlling for Identity Covariates.

Note.Gender identity (cis = 0 vs. trans = 1); sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, or heterosexual = 1 vs. others = 0); race (Caucasian-Anglosaxon/White = 0 vs. others = 1); rurality (rural = 0 vs. urban = 1); DHEQ = Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire.

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine minority stressors among LGBTQ+ adults from Spain. Our results provide a lens for understanding daily heterosexist experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals in Spain by providing a Spanish translation of the DHEQ and an insight into the rates of distal and proximal stressors among LGBTQ+ adults. In line with our first hypothesis, findings indicated a good fit for the six dimensions of the DHEQ scale among LGBTQ+ adults from Spain. Akin to prior findings in LGBTQ+ adult samples from United States and Poland (Balsam et al., 2013; Mijas & Kosiara, 2020), our factor analytic findings of the six DHEQ dimensions suggest that it has good psychometric properties as a measurement tool for use in future studies. The analysis of the construct validity and measurement invariance of the DHEQ Spanish version in other Spanish-speaking countries (i.e., Mexico, Argentina, Colombia) is suggested as a future research direction.

It is noteworthy that the prevalence rates of the six minority stressors were like prior documented rates in USA and Poland samples (Balsam et al., 2013; Mijas & Kosiara, 2020). This trend suggests the similarities and pervasiveness of the problem of heterosexism faced by LGBTQ+ individuals across different cultures as well as the persistent need to address the problem despite the recent documented advances on LGBTQ+ rights in many countries. Further studies should continue the examination of the occurrence of heterosexist experiences across samples from diverse cultural backgrounds. Research on the prevalence of heterosexist experiences and their cumulative effect on mental health will be the basis to adapt current stress-reduction interventions (i.e., Affirmative Supportive Safe and Empowering Talk [ASSET; Craig et al., 2014]; Expressive Writing [Lewis et al., 2015]; [REDUCE; Cook et al., 2022]) aimed to help LGBTQ+ people to overcome the discomfort experienced due to prevalent minority disadvantages and challenges (Jabson & Patterson, 2019; Pachankis et al., 2015). Moreover, clinicians from Spain should assess for minority stressors when working with LGBTQ+ treatment-seeking adults. This practice is already a part of the evidence-based treatments in the USA (see Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men [ESTEEM]). Addressing minority stressors when working with LGBTQ+ samples has shown to be effective to empower clients to take the lead in defining their own values and beliefs in their words as well as to navigate their way for social connections in stigma-laden locals (Pachankis, 2018; Pantalone et al., 2017).

An unexpected finding of this study was the existence of a lesser rejection experienced in Spanish families towards sexual orientation and gender diverse individuals. This finding may suggest that the local public and political trends may be in fact making changes in the values and attitudes of the Spanish population. However, conclusions on the topic should be addressed with caution. Recent national news highlights the increase in hate crimes and hate speech disseminated by some political parties in Spain and in the media, perhaps as a refractory movement of the LGBTQ+ movements (La Sexta, 2021; RTVE, 2021). Future studies should explore the cultural components of Spanish families given the cultural importance of the family environment in the development of coping mechanisms and response to stressful situations in academic, occupational, and social contexts (Kagitcibasi, 2017).

Regarding the second aim of the study, our results corroborated the different rates of prevalence of distal and proximal stressors across different minority sexual orientations and gender identities (Kattari et al., 2020; Schmitz et al., 2020; Shramko et al., 2018; Su et al., 2016). In line with prior literature, our findings suggested that TGD and sexual orientations other than gays or lesbians face greater exposure to heterosexism and cissexism. These findings align with the calls from researchers and advocacy groups to extend the minority stress framework by taking an intersectional lens (Cole, 2009; Tan et al., 2020). Future social and institutional practices should address the experiences of stress and discrimination at the intersection of simultaneous membership to diverse social statuses (whether privileged or oppressed) to identify those populations at greater risk and develop preventive strategies and informative campaigns. Special attention should be paid to prior documented heterosexism risk and protective factors among marginalized identities, such as the availability of social support, community connectedness, self-esteem, and self-compassion in LGBTQ+ individuals. Such variables could explain the higher chances of experiencing distal and proximal stressors related to their sexual orientation and gender identity (McConnell, et al., 2018; Morandini, et al., 2015; Williams, et al, 2020).

Finally, regarding the third aim of our study, there was a high prevalence of suicidal behavior and depression among the participants, specifically, nearly half of the sample met the cut off criteria for suicidality and depression. These rates are above average when compared with community samples (Gómez-Romero et al., 2021; Marcos-Nájera et al., 2018) and are similar to those found in clinical samples from Spain (47%-46%; Diez-Quevedo et al., 2001; Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2017). Moreover, these findings are in line with the high rates of depression and suicidality found in LGBTQ+ adults from other countries (The United States [54% depression, 50% non-suicidal self-injury, 28% suicidal attempt; Atteberry-Ash et al., 2021], Canada [65% suicidal ideation, 14% suicidal attempts; Igartua et al, 2003; 43% depression, New Zealand [31.7% suicidal behavior, 32.3% depression], Thailand [39% suicidal ideation; Kittiteerasack, 2021), and China [42.82% depression; Wang et al., 2021]) and suggest that despite the increasing changes in cultural and attitudinal values regarding LGBTQ+ rights, identifying as a LGBTQ+ individual still represents a risk factor for mental health problems. Special attention should be paid to how experiences of discrimination and rejection could lead to an increased level of depression and suicidal behavior. Prior research has suggested that variables such as LGBTQ+ identity concealment, emotional regulation, and experiences of revictimization could eventually exacerbate stress, anxiety, and depression (Talley & Bettencourt, 2011). More research on these mechanisms across LGBTQ+ samples is desirable.

Limitations

The present study findings should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, the study was based on a convenience sample. The sample was relatively homogeneous, most of the participants had a college education, and most of them identified as Caucasian. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalized to the LGBTQ+ adult population from Spain. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow to assume causality among the study variables, and the assumption that minority stressors precede depression and suicidal behavior risk is based on the minority stressors theory (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003). Third, the present study used an online sampling strategy. The questionnaires were self-reported via Qualtrics/online. Although social media recruitment has proved to be an effective strategy for approaching and recruiting "hard-to-reach populations" such as LGBTQ+ people, this recruitment strategy limits the sample to those with access to the internet. Moreover, not all potential participants may have been made aware of this study advertisement. Thus, the study sample may not be representative of the target population (Topolovec-Vranic & Natarajan, 2016). Fourth, only six dimensions of the DHEQ were analyzed in this study; thus, factor structure, reliability, and validity of the full DHEQ could not be tested. Future studies should aim to analyze more evidence of the validity and reliability of the full DHEQ.