Introduction

Drug use is a major global risk factor for disability and premature loss of life (Peacock et al., 2018). Drug use seriously harms correct functioning and is related to problems and difficulties (Mauro et al., 2018; Newcomb & Bentler, 1988; Shao et al., 2023; Spear, 2018). For example, drug use has been associated with low well-being, poor family relationships and emotional regulation, low confidence in one's abilities (Fuentes et al., 2020), weak performance at school or work (Lehman & Simpson, 1992; Mounts & Steinberg, 1995), poor interpersonal relationships (Newcomb, 1994), and increased likelihood of deviant activities and even delinquency (Farrell et al., 2000).

Despite the efforts of public authorities to reduce drug use rates among the population, global statistics on alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use revealed the highest prevalence, particularly in United States and Europe (Peacock et al., 2018). Drug use is likely to begin in adolescence, mainly alcohol and tobacco, even though in adulthood, especially among young adults, the rates seem to remain equal or even higher than in adolescents (Evans-Polce et al., 2015; Peacock et al., 2018; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Individual differences identified in drug use, personal functioning, and psychosocial deviance are related to multiple protective or risk factors. Even though family is one of the most important, due to their influence, it can be beneficial and protective, but also harmful and risky.

Parenting Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment

For years, the study of parental socialization has been carried out through a theoretical model of two non-related dimensions and four parenting styles (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). The warmth dimension, also called involvement, love and responsiveness, refers to the capacity to get involved in the upbringing of their children, by showing support and affection, being receptive and available to any type of problem, using open and bidirectional communication, based on understanding and reasoning (Baumrind, 1991a; Gimenez-Serrano, Alcaide et al., 2022; Martínez et al., 2017). The strictness dimension, also called imposition, control, severity or demandingness, refers to the control and surveillance over the children, as well as the way in which parents impose rules in a punitive and rigid manner (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Martinez et al., 2019; Riquelme et al., 2018). From the combination of both dimensions, four parenting styles are obtained: authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful. Authoritative parents are characterized by using warmth with strictness; indulgent parents use warmth without strictness; authoritarian parents are characterized by using strictness without warmth, whereas neglectful parents do not use warmth nor strictness (Fuentes et al., 2022; Lamborn et al., 1991; Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Palacios et al., 2022).

Overall, most classical studies mainly conducted with European-American families identify the use of high parental strictness as a protective factor against drug use and other problems such as school misconduct and poor school engagement (Bahr & Hoffmann, 2010; Im-Bolter et al., 2013; Lamborn et al., 1991; Stephenson & Helme, 2006). However, only the combination of high strictness and high warmth (i.e., authoritative parenting) seems to be associated with optimal scores in terms of psychosocial adjustment (e.g., self-confidence and self-concept) and protection against behavioral problems (e.g., school misconduct and delinquency) (Baumrind, 1991a; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1992; Steinberg et al., 1994). Adolescents with authoritarian parents benefit from the strictness component (common to authoritative parents) by scoring reasonably well on measures of obedience and conformity to adult standards, which offers protection against drug use and behavioral problems. However, lack of parental warmth seems to negatively affect self-confidence in their abilities, reporting poor self-concept (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994; Steinberg et al., 2006). On the contrary, adolescents with indulgent parents (characterized by lack of strictness) are those who have greater problems at school, drug use and even delinquency, although they benefit from the warmth component (common with authoritative parents) reporting greater self-confidence and self-concept. Finally, adolescents from families lacking strictness and warmth (neglectful parents) consistently obtain the most negative scores (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994; Steinberg et al., 2006).

Despite parental socialization being always conducted by parents through warmth and strictness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983), positive parenting aiming to foster a healthy development is not always the same (Palacios et al., 2022). Some research seriously questions the universal benefits of the authoritative parenting for all cultural contexts (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Garcia et al., 2019; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Studies conducted with ethnic minorities in the United States, such as African-American (Baumrind, 1972; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996) or Chinese-American (Chao, 1994; Chao, 2001), reveal that authoritarian parenting might be related to some benefits. Especially in dangerous and poor communities, in which disobeying family rules (e.g., initiation with drugs or school misconduct) might be related to more damaging consequences for child development than in middle-class neighborhoods (Gracia et al., 1995; Sandoval-Obando et al., 2022), parental strictness even without warmth might provide the family protection and security that the neighborhood does not offer (Baldwin et al., 1990; Baumrind, 1972; Clark et al., 2015; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996). In a similar line, some psychosocial gains associated with authoritarian parenting have been identified in studies conducted with families from Arab or Asian countries (Dwairy & Achoui, 2006; Dwairy et al., 2006; Wang & Tamis-LeMonda, 2003).

Additionally, some recent research from studies mostly conducted in European and Latin American countries indicate that the indulgent parenting is related to equal or even more optimal scores compared to the authoritative parenting, whereas authoritarian and neglectful parenting tend to be related to the lowest optimal scores (Alcaide et al., 2023; Calafat et al., 2014; Garcia et al., 2019; Martinez et al., 2020; Perez-Gramaje et al., 2020; Reyes et al., 2023). Overall, parental warmth might offer broad benefits (Lila et al., 2007; Martinez-Escudero et al., 2023), while parental strictness seems to be unnecessary or even detrimental (Climent-Galarza et al., 2022; Martinez et al., 2019). For example, a European study with adolescents conducted in six countries (Sweden, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Portugal) indicated that parenting styles characterized by warmth (i.e., authoritative and indulgent styles) offer more protection against drug use and personal disturbances than parenting based on lack of warmth with strictness (authoritarian style) and without strictness (neglectful style). Furthermore, adolescents from indulgent homes reported greater self-esteem and school performance than their peers from authoritative homes (poor scores were reported again by those from authoritarian and neglectful families) (Calafat et al., 2014).

Similar results about the benefits of indulgent parenting were found on the internalization of social and environmental values (Martinez et al., 2020; Queiroz et al., 2020), empathy (Martinez-Escudero et al., 2020), and school adjustment (Fuentes et al., 2015). In the same way, parenting characterized by warmth without strictness (i.e., the indulgent style) has also been related to lower drug use (Garcia, Serra et al., 2020; Riquelme et al., 2018) and criminal behaviors (Martínez et al., 2013). Additionally, some other studies conducted with adult children revealed the benefits of indulgent parenting beyond adolescence. Interestingly, adult children who were raised in warm but not strict homes reported high psychological maturity, less emotional maladjustment (Garcia & Serra, 2019), greater internalization of social values (Garcia et al., 2018), and more well-being (Garcia, Fuentes et al., 2020).

Family and Extrafamilial Influences during Adolescence and Adulthood

The family is not an exclusive and isolated context where socialization takes place; there are other intra- and extra-familial influences such as school, peers, or mass media which positively or negatively affect healthy development, especially in adolescents (Garcia, Serra et al., 2020; Steinberg & Morris, 2001; Veiga et al., 2021). Adolescence seems to be a critical time related to some degree of psychosocial vulnerability or difficulties compared to childhood and adulthood (Arnett, 1999; Riquelme et al., 2018; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Adolescents spend more time with their peers without adult supervision (Veiga et al., 2015). Parents have an important influence in adolescence, although this tends to diminish (Steinberg & Morris, 2001; Veiga et al., 2021) at the same time that peer influence increases (Musitu-Ferrer et al., 2019). Some problems can appear in adolescence such as drug use (Riquelme et al., 2018), less self-concept (Harter, 1988), poor academic achievement and school misconduct (Lamborn et al., 1991), aggression (Gallarin et al., 2021), and even delinquency (Garcia & Gracia, 2009).

Adolescents are more likely to explore psychological characteristics of the self to discover who they really are, and how they fit in the social world in which they live (Harter, 1988; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Peers can positively help adolescents to achieve autonomy, independence and identity, although peers could also influence adolescents in a negative way. Social norms transmitted in the socialization process by different agents, including the family, are not always followed by adolescents. Peer approval may be based less on social standards and more on conformity to peer standards that sometimes deviate from social norms (Eccles et al., 1993; Fuentes et al., 2015). For example, school success may be devalued by peers and negatively associated with students' social standing, increasing the likelihood of school misconduct or lower academic engagement (Baumrind, 1991b; Preckel et al., 2013). Fear of rejection may also lead the adolescent to engage in deviant activities within the peer group, such as using drugs in their free time, mainly alcohol and marijuana (Peacock et al., 2018), or even delinquency (Steinberg et al., 2006). On the contrary, an effective socialization is achieved when adolescents develop confidence in oneself and others, good social abilities, and emotional regulation and can reject peer pressure toward standards that deviate from the social norm (Baumrind, 1991a; Garcia, Fuentes et al., 2020; Steinberg & Morris, 2001).

Adulthood represents the end of parental socialization, even though the relationship between parents and adult children tends to continue. Parents can no longer use parental practices with their adult children (e.g., monitoring or behavioral control). Adults throughout their lives face different challenges, such as university studies and job search (mainly in young adulthood), consolidation of professional career and family life (in middle age) and retirement and perhaps grandparenthood (later life) (Alcaide et al., 2023). Far from some problems that may arise during adolescence being reduced upon reaching adulthood, findings suggest that they seem to continue. For example, drug use; rates appear to be the same or even higher during young adulthood, as identified for alcohol (Barry & Blow, 2016; Merrill & Carey, 2016; Windle, 2016) and others such as tobacco and marijuana (Evans-Polce et al., 2015; Mauro et al., 2018; Webb et al., 1996). Family studies have focused on examining parenting correlates when parental socialization is in process (i.e., childhood and adolescence) (Baumrind, 1971; Baumrind, 1972; Calafat et al., 2014; Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994), but less is known about whether differences in adjustment and competence among adult children might depend on parental socialization (Garcia, Martínez et al., 2018; Gimenez-Serrano, Garcia et al., 2022; Villarejo et al., 2020).

The Present Study

There are important individual differences in drug use and psychosocial adjustment. Some adolescents and adults tend to use drugs and have worse psychosocial adjustment than their age peers. Despite several intrafamilial and extrafamilial influences on development, differences between lower and higher scores on drug use and psychosocial adjustment can be related to parental socialization. For years, family studies have focused on the assessment of parental socialization based on a theoretical model of two non-related dimensions and four parenting styles (Maccoby & Martin, 1983).

The strictness dimension has been identified to offer greater benefits when combined with warmth (i.e., the authoritative style) and even without it (i.e., the authoritarian style) in protecting against deviance, including drug use and some behavioral problems (Lamborn et al., 1991; Stephenson & Helme, 2006). However, the so-called positive parenting (i.e., authoritative parenting), the family style that has been found to be protective not only against drugs, but also for fostering psychosocial adjustment, may not always be effective. Some recent studies revealed that the optimal scores might be related to parental warmth, even without strictness (indulgent parenting) (Calafat et al., 2014; Garcia et al., 2019). Additionally, some previous research has focused primarily on the association between parenting and drug use (Garcia, Serra et al., 2020a; Stephenson & Helme, 2006), without considering different indicators of psychosocial adjustment, or have examined parental socialization considering parental practices without the general context of the parenting styles (Martins et al., 2008; Montgomery et al., 2008). Furthermore, family studies tend to be examined only in a single developmental time period, mainly when parental socialization is in process (e.g., adolescence) (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991), but without considering adulthood (i.e., when parental socialization is over).

The present study examined if parenting styles (i.e., indulgent, authoritative, authoritarian, and neglectful) are associated with differences in drug use, and in different indicators of psychosocial adjustment across adolescence and adulthood (young adulthood, middle-age and later life): self (emotional and family self-concept and self-esteem), social competence, externalizing problems during adolescence (school misconduct and delinquency), and behavioral and psychological problems (aggression, emotional unresponsiveness, and nervousness). Considering some recent studies, we hypothesized that indulgent parenting would be related to equal and even more positive scores than authoritative parenting, whereas parenting characterized by lack of warmth (authoritarian and neglectful styles) would be associated with worse scores.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample consisted of 2,095 participants from Spain, 1,227 females (58.6 %) and 868 males (41.4 %), with adolescents and adult children (M = 36.19, SD = 20.34, ranged from 12 to 91 years) from four age groups: adolescents (n = 581, 348 females, 59.9 %), aged 12 to 18 years (M = 16.67, SD = 1.63); young adults (n = 616, 362 females, 58.8 %) aged 19 to 35 years (M = 23.70, SD = 3.76); middle-aged adults (n = 505, 319 females, 63.2 %) aged 36 to 59 years (M = 48.44, SD = 6.26); and older adults (n = 393, 198 females, 50.4 %) aged 60 years or older (M = 68.86, SD = 7.77). Following the a priori power analysis, a minimum sample of 1,020 participants was determined as necessary to reach detection with a statistical power of .95 (α = .05; 1 – β = .95) of the low effect size, f = 0.13. The total sample of this study goes beyond the minimal sample size required (Faul et al., 2007; Pérez et al., 1999). A sensitivity power analysis showed that for the study sample (N = 2095, α = β = .05) it is possible to detect a statistically significant main effect among the four parenting styles for a very small effect size (f = 0.091; Alcaide et al., 2023; Faul et al., 2009; Garcia & Gracia, 2010). G-power 3.1 software was applied to estimate the statistical power (Faul et al., 2009).

The data collection procedure followed in this study was similar to previous studies on socialization with adolescent and adult children (Garcia & Serra, 2019; Garcia et al., 2021; Villarejo et al., 2020). Specifically, adolescents were enrolled through the complete list of high schools. First, the heads of all the high schools invited to participate were contacted. If a head declined to be part of the research, another school from the complete list was selected until achieving the sample size needed (Garcia et al., 2018; Martínez et al., 2021). Young adults were recruited from university courses (Candel, 2022; Manzeske & Stright, 2009). Middle-aged adults came from city council neighborhoods (Alcaide et al., 2023; Climent-Galarza et al., 2022). Older adults were recruited using a complete list of senior citizen centers. If a senior citizen center rejected to participate, an alternative center from the complete list was selected until achieving the sample size required (Garcia et al., 2018; Gimenez-Serrano, Garcia et al., 2022). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the country in which the research was carried out. Participants met these requirements: a) they were Spanish, as well as their parents and grandparents; b) they participated voluntarily; c) parental consent was mandatory for adolescents; d) informed consent was required; and e) anonymity of responses was guaranteed.

Measures

Parental Socialization

The warmth dimension was measured with the 20 items of the Warmth/Affection Scale (Rohner et al., 1978). It assesses the extent to which adolescent and adult children perceive their parents as affectionate, responsive, and involved. A sample item is “Make me feel wanted and needed”. For the three adult groups, there is an adult version that includes the same statements in past tense. A sample item is “Made me feel wanted and needed”. The alpha value was .903. The strictness dimension was measured with the 13 items of the Parental Control Scale (Rohner et al., 1978). It assesses the extent to which adolescent and adult children perceive control, firmness, demand, severity, and imposition by their parents. A sample item is “Want to control whatever I do”. For the three adult groups, there is an adult version that includes the same statements in past tense. A sample item is “Wanted to control whatever I did”. The alpha value was .900. Both scales are 4-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 = almost never is/was true to 4 = almost always is/was true. High scores on both scales represent greater warmth and parental strictness. Overall, parenting questionnaires for adult children have the same items as for adolescents, but are written in past tense (Arrindell et al., 1999; Buri, 1991; Rohner et al., 1978). Both the Warmth/Affection Scale and the Parental Control Scale are frequently used in studies across the world and have good psychometric properties (Gomez & Rohner, 2011; Khaleque & Rohner, 2002a, 2002b; Rohner & Khaleque, 2003; Senese et al., 2016).

The four parenting styles were defined based on the median split procedure (50th percentile) in both parental dimensions (i.e., warmth and strictness) by sex and age of the participants (Garcia, Fuentes et al., 2020; Lamborn et al., 1991; Queiroz et al., 2020). Authoritative families scored above the median on warmth and strictness, whereas neglectful families were below the median on both parental dimensions. Authoritarian families scored above the median on strictness and below the median on warmth, whereas indulgent families scored above the median on warmth, but below the median on strictness.

Drug Use

Drug use in adolescents and in the three adult age groups was examined (Sanjuan & Langenbucher, 1999). It was measured by four indices (items), each one assesses a different substance (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991). The measure of current drug use taps the frequency of involvement with alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. The alpha value was .680. Its response scale is a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = nothing to 4 = much. Greater scores indicate higher drug use.

Psychosocial Adjustment

Self. It was captured through three indicators: emotional self-concept, family self-concept, and self-esteem. Emotional self-concept was measured with the 6 items of the emotional scale from the AF5 Self-Concept Form 5 (Chen et al., 2020; Garcia & Musitu, 1999). This scale evaluates the general self-perception of the emotional state and its response to specific situations of daily life that require a certain degree of commitment and involvement (Fuentes et al., 2020; Gracia, Martinez et al., 2018). A sample item is “I am afraid of some things” (reversed item). The alpha value was .768. Family self-concept was measured with the 6 items of the family scale from the AF5 Self-Concept Form 5 (Chen et al., 2020; Garcia & Musitu, 1999). This scale assesses the perception that individuals have of their involvement, participation, and integration in the family. A sample item is “My family would help me with any type of problem”. The alpha value was .822. The response scale of the emotional and family self-concept measures is a 99-point scale, ranging from 1 = very little agreement to 99 = very much agreement. Self-esteem was measured with the 10 items of the Rosenberg questionnaire (Rosenberg, 1965). This instrument evaluates feelings of self-worth, self-respect, and self-acceptance. A sample item is “I am able to do things as well as most other people”. The alpha value was .854. Its response scale is a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Higher scores correspond to higher emotional self-concept, family self-concept, and self-esteem.

Social Competence. Social competence was measured with the 8 items of the social competence scale of the Psychosocial Maturity Questionnaire (CRPM3) (Garcia & Serra, 2019; Greenberger et al., 1975; Zacares & Serra, 1996). It assesses the development of effective interpersonal relationships with peers and adults (Baumrind, 1978; Greenberger et al., 1975). A sample item is “I adapt successfully to different people and social situations”. The alpha value was .832. Its response scale is a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = very inadequate to describe me to 5 = very suitable to describe me. A high score on social competence represents greater personal adjustment.

Externalizing Problems during Adolescence. It includes self-reports of all participants regarding two indices, their school misconduct and delinquency during adolescence (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991). The measure of school misconduct assesses the frequency of such behaviors as cheating, copying homework, and tardiness. A sample item is “Misrepresenting a classmate in homework or assignments on purpose”. The alpha value was .613. The measure of delinquency assesses the frequency of behaviors such as carrying a weapon, theft, and getting into trouble with the police. A sample item is “Taking goods from supermarkets (or department stores)”. The alpha value was .657. Its response scale is a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never to 3 = two or more times. Higher scores in school misconduct and delinquency represent higher externalizing problems during adolescence.

Behavioral and Psychological Problems. It was captured through three indicators: aggression, emotional unresponsiveness, and nervousness. Aggression was measured with the 6 items of the Hostility/Aggression Scale of the Personality Assessment Questionnaire (PAQ) (Rohner, 1978). It evaluates personality self-perception and behavioral traits linked to hostile and aggressive tendencies (Ali et al., 2015). A sample item is “I have trouble controlling my temper”. The alpha value was .652. Emotional unresponsiveness was measured with the 6 items of the emotional unresponsiveness scale of the Personality Assessment Questionnaire (PAQ) (Rohner, 1978). It assesses the inability to express emotions freely and openly and is manifested by a lack of spontaneity and difficulty in responding emotionally to other's demands (Gracia et al., 2005). A sample item is “I have trouble showing people how I feel”. The alpha value was .723. The response scale of the aggression and emotional unresponsiveness measures is a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = almost never true to 4 = almost always true. Nervousness was measured with the 8 items of the nervousness scale of the Psychosocial Maturity Questionnaire (CRPM3) (Garcia & Serra, 2019; Garcia et al., 2021; Greenberger et al., 1975; Zacares & Serra, 1996). It evaluates the lack of emotional stability and anxiety in situations in everyday life (Martinez-Escudero et al., 2020). A sample item is “I am usually tense, nervous, and anxious”. The alpha value was .769. Its response scale is a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = very inadequate to describe me to 5 = very suitable to describe me. Higher scores on aggression, emotional unresponsiveness and nervousness represent higher personal maladjustment.

Data Analysis

First, a factorial multivariate analysis of variance (4 × 2 × 4 MANOVA) was performed for drug use, self (emotional self-concept, family self-concept, and self-esteem), social competence, externalizing problems during adolescence (school misconduct and delinquency), and behavioral and psychological problems (aggression, emotional unresponsiveness, and nervousness). Independent variables were parenting style (i.e., indulgent, authoritative, authoritarian and neglectful), sex (i.e., female and male), and age group (i.e., adolescents, aged 12 to 18 years; young adults, aged 19 to 35 years; middle-aged adults, aged 36 to 59 years; and older adults, aged 60 years or more). Second, a univariate analysis (ANOVA) was applied in those multivariate sources of significance. Finally, maintaining the alpha per study at 5%, post-hoc Bonferroni tests were applied to those univariate sources of significance.

Results

Parenting Style Groups

Participants were distributed in the four parenting styles (see Table 1). Regarding parental warmth, children from indulgent (M = 73.73, SD = 4.37) and authoritative (M = 72.7, SD = 4.13) families scored higher than those from authoritarian (M = 54.96, SD = 10.05) and neglectful (M = 57.22, SD = 9.27) families. In terms of parental strictness, children from authoritative (M = 39.89, SD = 4.93) and authoritarian (M = 41.93, SD = 5.47) families scored higher than their peers from indulgent (M = 28.47, SD = 5.43) and neglectful (M = 28.59, SD = 5.78) families.

Multivariate Analyses

The results of the multivariate analyses (see Table 2) showed statistically significant differences in the main effects of parenting style, Λ = .707, F(30.0, 6029.6) = 25.21, p < .001, sex, Λ = .812, F(10.0, 2054.0) = 47.53, p < .001, and age, Λ = .834, F(30.0, 6029.6) = 12.78, p < .001, and in the interaction effects of parenting style by age, Λ = .930, F(90.0, 13941.2) = 1.67, p < .001, and sex by age, Λ = .964, F(30.0, 6029.6) = 2.52, p < .001.

Table 2. MANOVA Factorial (4a × 2b × 4c) for Drug Use, Self (emotional and family self-concept, and self-esteem), Social Competence, Externalizing Problems during Adolescence (school misconduct and delinquency), and Behavioral and Psychological Problems (aggression, emotional unresponsiveness, nervousness).

Note.(A) Parenting styles = a1 indulgent, a2 authoritative, a3 authoritarian, a4 neglectful; (B) sex = b1 female, b2 male; (C) age = c1 adolescents (12-18 years), c2 young adults (19-35 years), c3 middle-aged adults (36-59 years), and c4 older adults (60 years and older).

Parenting Styles

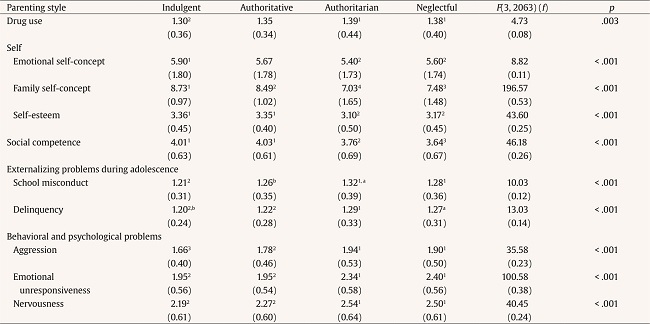

The results of the univariate analyses showed statistically significant differences of the parenting styles in all criteria, p < .05 (see Table 3). Parenting styles characterized by warmth (i.e., indulgent and authoritative) were related to more positive scores than families not characterized by warmth (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). However, indulgent parenting was the only parenting style constantly related to low drug use and greater psychosocial adjustment in both adolescent and adult children.

Table 3. Means (standard deviations), Univariate F-values, (Cohen f) and Bonferroni test# for Parenting Styles on Drug Use, Self, Social Competence, Externalizing Problems during Adolescence and Behavioral and Psychological Problems.

Note. #Bonferroni test α = .05; 1 > 2 > 3 > 4; a > b.

In terms of drug use, the lowest scores corresponded to adolescents and adult children from indulgent families (i.e., warmth without strictness), whereas the highest rates were obtained by those from non-warmth families (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). Additionally, no differences were found between authoritative style and the other parenting styles.

With regard to self-concept and self-esteem, adolescents and adult children who characterized their parents as indulgent obtained the most positive scores. In terms of emotional self-concept, adolescents and adult children from indulgent families scored higher than those raised in authoritarian and neglectful families, whereas those from authoritative families did not differ significantly from their peers of other family profiles. Again, regarding family self-concept, indulgent parenting was related to the greatest scores followed by authoritative, neglectful and authoritarian parenting. Additionally, a statistically significant interaction effect between parenting style and age was found on family self-concept, F(9, 2063) = 6,179, p < .001. Examining the family profiles by age in family self-concept (see Figure 1), a common pattern can be observed for adolescents and adult children: parenting characterized by warmth (i.e., indulgent and authoritative) was associated with higher family self-concept than parenting not characterized by warmth (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). Within households characterized by warmth, family age profile showed that indulgent parenting was related to higher scores than authoritative parenting in adolescence and young adulthood but tend to be equal in middle age and later life. Within homes characterized by non-warmth, family age profiles showed that neglectful parenting was related to higher scores in family self-concept than authoritarian parenting in adolescence, young adulthood and middle age but in later life the scores were lower than in authoritarian. Regarding self-esteem, indulgent and authoritative parenting were related to higher scores compared to authoritarian and neglectful parenting.

Figure 1. A structural Model Relating Father's and Mother's Parenting Styles and Interaction of Parenting Style by Age on Family Self-concept.

In terms of social competence, adolescents and adult children from families characterized by warmth (i.e., indulgent and authoritative parenting) reported higher scores than those from neglectful and authoritarian families. Additionally, within parenting not characterized by warmth, those with neglectful parents reported lower social competence than their peers from authoritarian homes.

With regard to externalizing problems during adolescence, warm parenting was associated to lower scores compared to non-warm parenting. Specifically, the lowest scores on school misconduct corresponded to the indulgent parenting and the highest to the authoritarian and neglectful parenting. Additionally, adolescents and adult children from authoritative parenting scored better than their peers from authoritarian parenting. Similarly, with regard to the other indicator of externalizing problems during adolescence, indulgent and authoritative parenting were associated with lower delinquency than authoritarian and neglectful parenting.

In terms of behavioral and psychological problems, the indulgent parenting was also the only parenting style related to the lowest scores. Differences on aggression showed that the less aggressive adolescents and adult children were from indulgent families, those from authoritarian and neglectful homes were the most aggressive, and in a middle position were children from authoritative households. In terms of emotional unresponsiveness, indulgent and authoritative parenting were associated with lower scores than authoritarian and neglectful parenting. In the same way, children from indulgent and authoritative homes reported less nervousness than their peers from authoritarian and neglectful homes.

Sex and Age Differences

Although not central to the objective of this study, several univariate main effects for sex and age reached significance (see Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4. Means (standard deviations), Univariate F-values and (Cohen f) for Sex on Drug Use, Self, Social Competence, Externalizing problems during adolescence and behavioral and psychological problems.

Table 5. Means (standard deviations), Univariate F-values, (f Cohen) and Bonferroni Test# according to Age Group for Drug Use, Self, Social Competence, Externalizing Problems during Adolescence and Behavioral and Psychological Problems.

Note. #Bonferroni test α = .05; 1 > 2 > 3 > 4; a > b.

Regarding sex-related differences, drug use was higher in males than among females. Males scored higher on emotional self-concept and self-esteem scores, but less on family self-concept scores. Females reported greater social competence than males. In terms of externalizing problems during adolescence, males reported higher school misconduct and delinquency than females. Males also reported more aggression and emotional unresponsiveness than females, whereas females scored higher in nervousness.

Regarding age-related differences, young adults reported higher drug use than adolescents and middle-aged adults, whereas the lowest scores were reported by older adults. Middled-aged and older adults had higher emotional self-concept than adolescents and young adults, while older adults reported the lowest scores on family self-concept (there were no differences between the other age groups). Middle aged adults scored higher on self-esteem than young adults, who reported greater scores than adolescents (older adults scored higher than adolescents). In terms of social competence, adolescents and young adults had better scores than older adults. For school misconduct, young adults reported higher rates than adolescents who scored higher than middle-aged adults, while the lowest scores were reported by older adults. In a similar way, the lowest scores on delinquency corresponded to older adults, but the highest to young adults (adolescents and middle-aged adults scored in a middle position). Aggression was greater in adolescents followed by young adults, whereas the lowest scores corresponded to middle-aged and older adults. Regarding emotional unresponsiveness, adolescents and adolescents and young adults scored higher than middle-aged adults. Finally, adolescents and young adults scored higher than middle-aged adults on nervousness, whereas older adults reported lower scores than adolescents.

Figure 2. Interaction of Sex by Age on the Family Self-concept (a) and Emotional unresponsiveness (b).

Additionally, statistically significant effects between sex and age were found in family self-concept, F(3, 2063) = 3.456, p = .016 and emotional unresponsiveness, F(3, 2063) = 4.100, p = .007.

Examining the sex profiles by age in family self-concept (see Figure 2a), females were found to score higher than males throughout life with the exception of middle-aged adults. Throughout the life cycle, males and females have an increasing tendency and then a decreasing tendency but the point in the life cycle at which this change occurs is different for males and females: young adulthood for females and middle age for males. Due to the fact that females have higher family self-concept scores than males in almost the entire life cycle and the point in the life cycle at which the decreasing tendency starts is earlier than in males, the declining tendency is more abrupt in females than in males.

Examining the sex profiles by age in emotional unresponsiveness (see Figure 2b), a common pattern was found: males scored higher than females in almost the entire life cycle with the exception of male adolescents, who scored similar to their female counterpart. In addition, there was a decreasing tendency from young adulthood to middle age, but only in females. Males did not present this decreasing tendency, being related to similar levels of emotional unresponsiveness throughout life.

Discussion

Based on the two-dimensional model (i.e., warmth and strictness), the study examines the relationship between the four parenting styles (indulgent, authoritative, authoritarian and neglectful) and drug use, self (emotional self-concept, family self-concept, self-esteem), social competence, externalizing problems during adolescence (school misconduct and delinquency), and behavioral and psychological problems (aggression, emotional irresponsibility, nervousness) among adolescent and adult children. Differences in the ten criteria examined were found depending on parenting style. For adolescents and adult children, non-warm parenting (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful) was related to poor scores, whereas parenting characterized by warmth, indulgent parenting (i.e., without strictness) was associated with equal or even better positive scores than authoritative parenting (i.e., with strictness).

Results from the present study disagree with those obtained from European-American families, in which parental strictness combined with warmth (i.e., the authoritative style) is constantly beneficial for healthy development. However, according to the present data, parental warmth offers the highest protection, not only against drug use, but also against psychosocial maladjustment. Parental strictness seems unnecessary or even detrimental. Interestingly, differences in drug use and psychosocial adjustment depending on parenting styles share the same pattern during adolescence and beyond.

In terms of drug use, only adolescents and adult children raised by indulgent families reported the lowest scores, whereas their peers from authoritarian and neglectful homes obtained the highest rates. The present findings seriously contradict those from European-American families in which parental strictness without warmth (i.e., the authoritarian style) and combined with warmth (i.e., the authoritative style) offers protection against drug use, whereas the highest rates corresponded to adolescents with non-strict families (i.e., indulgent and neglectful parenting) (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994). However, the present findings seem to suggest that parental warmth is associated with protection, regardless of parental strictness. The greatest drug use corresponds to families characterized by lack of warmth, including those without strictness (neglectful parents) and those families characterized by strictness (authoritarian parents). Parenting based on warmth without strictness (indulgent style) is related to the lowest drug use, whereas parenting characterized by warmth and strictness (authoritative style) is related to relative low scores that do not reach statistically significant levels compared to the other families. These results confirm the protection of indulgent parenting against drug use identified in some emergent research mainly conducted in Spain (Garcia, Serra et al., 2020) and other European countries (Calafat et al., 2014).

Drug use seriously harms the correct personal functioning and is related to problems and difficulties. However, some previous studies have only considered the relationship between family and drug use in adolescence (Garcia, Serra et al., 2020; Stephenson & Helme, 2006). The present study extends the research of family beyond drug use to the broader aspects of psychosocial adjustment, which are quite relevant for the health and well-being, not only during adolescence (as most previous family studies focus on) but also across adulthood (young, middle-aged and older adult children). According to the present study, differences in psychosocial adjustment depending on parenting style also show a similar pattern as in drug use.

In terms of the self and social competence, the highest scores were only associated to parental warmth without strictness. Within families characterized by warmth, indulgent parenting is related to equal scores (on self-esteem and social competence) or better rates (on family self-concept) than the authoritative parenting. In terms of emotional self-concept, the greatest scores correspond to the indulgent parenting style, the lowest to the authoritarian and neglectful, and authoritative parenting was in a middle position, although differences did not reach a significant level and, therefore, did not differ from the other families. The results do not agree with most research conducted with European-American families in which the greatest adjustment (e.g., self-concept) corresponded to the authoritative parenting (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994), while it confirms some emergent research mainly conducted in European and South American countries about the benefits of the indulgent parenting style (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Garcia et al., 2019).

Also, the lowest externalizing problems during adolescence (school misconduct and delinquency) and the lowest behavioral and psychological problems (aggression, emotional unresponsiveness, and nervousness) were only associated with the indulgent parenting. Within parenting characterized by warmth, the indulgent style was related to the highest protection, being related to less aggression than the authoritative style. Also, strictness without warmth (i.e., authoritarian parenting) does not offer protection against psychosocial maladjustment, being as ineffective as the other parenting style without strictness (i.e., the neglectful). Parental warmth seems to be more effective at achieving adolescents and adult children that are guided by social standards which include taking care of oneself and others, whereas strictness seems unnecessary or even harmful. These results confirm some previous evidence, mainly from families of Europe and South America (Calafat et al., 2014; Martinez et al., 2020; Perez-Gramaje et al., 2020), but seriously contradict findings from research with European-American families (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994) and some US ethnic minority families and Eastern Societies in which protection might be associated to strictness even without warmth (Deater-Deckard et al., 1996; Dwairy & Achoui, 2006).

Important differences in child and adolescent adjustment and competence have long been related to parental socialization. Although parental socialization is always based on warmth and strictness, the cultural context in which it takes place is very different and could explain some discrepant research findings on the optimal parenting styles (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Garcia et al., 2019; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Warmth seems to be a protective factor against drug use, which could support children making social standards and norms their own by rejecting peer pressure when it is oriented towards socially deviant standards. Drug use is especially harmful not only because of its toxic effects, but also because it leads the human being to feel separated from the community, unable to find a shared interest and a consensual way to contribute to society (Baumrind, 1987). Warmth, but not strictness, also benefits psychosocial adjustment. Involvement, trust, and closeness in the family could favor adolescents and adult children by developing confidence to regulate emotions (emotional self-concept) and trusting their family (family self-concept), having a good view of oneself as a valuable person for society (self-esteem), and through skills needed to interact in the social world (social competence). According to the present findings, warm but not strict parents are more likely to help their children adequately develop their life within social norms, being equal or even more effective than parents that are also warm but strict.

An important limitation of some previous studies is that they relate parenting to a certain component of adolescent adjustment (e.g., school adjustment) (Glasgow et al., 1997), but do not consider the different adjustment components through various indicators (the present study uses 10 indicators). Despite multiple intra- and extrafamilial influences (Gomez-Ortiz et al., 2022; Gomez-Ortiz & Sanchez-Sanchez, 2022), parenting affects (positively or negatively) very different components of adjustment (see Baumrind, 1993). Parenting styles allow defining families according to the degree of warmth and strictness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). An important question is to identify the positive parenting style (the parenting style that is related to the optimal scores on different adjustment components). Based on research with mainly European-American families, parenting styles characterized by a lack of one of the two dimensions (i.e., authoritarian and indulgent parenting) are associated with a mixture of positive and negative outcomes (Baumrind, 1991a; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994). For example, adolescents with authoritarian parents show obedience and conformity to adult standards and low levels of drug use (benefit of high strictness), but also poor self-confidence (cost of lack of warmth). However, according to classical findings from mainly European-American families, only the combination of high strictness and warmth (i.e., the authoritative style) is related to the optimal developmental scores. Thus, adolescents with authoritative parents would show the highest psychosocial adjustment and the lowest drug use (Baumrind, 1991a; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994).

The main findings from the present study seriously question the combination of strictness and warmth (i.e., the authoritative style) as the only parenting style related to the most positive scores on drug use, social competence, externalizing problems during adolescence, and behavioral and psychological problems. The traditional so-called positive parenting style (i.e., authoritative parenting) seems to not be the most beneficial according to the present findings. By contrast, the benefits of the indulgent style have been identified in some previous emergent research mainly conducted in Europe and Latin America. For example, the indulgent parenting was related to equal or even more optimal scores in studies conducted in Spain (Garcia & Gracia, 2009, 2010; Reyes et al., 2023), Portugal (Rodrigues et al., 2013; Martinez et al., 2020), Germany (Garcia et al., 2019), Sweden, United Kingdom, Slovenia, the Czech Republic (Calafat et al., 2014), Norway (Lund & Scheffels, 2019), Brazil (Martinez & Garcia, 2008; Martinez et al., 2020), or more recently United States (Garcia et al., 2019; Milevsky, 2022). Additionally, similar results from South Africa revealed the benefits of parental warmth regardless of strictness (Dakers & Guse, 2020). However, the optimal parenting is a pressing issue, and more studies are needed. Classical and more recent research findings reveal variations in optimal parenting as a function of cultural context (Baumrind, 1972, Chao, 2001; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Pinquart & Gerke, 2019). Whether optimal parenting is based on strictness without warmth (the so-called first stage or authoritarian parenting), strictness with warmth (the so-called second stage or authoritative parenting), or warmth without strictness (the so-called third stage or indulgent parenting) continues to be analyzed in different contexts and settings throughout the world (Garcia et al., 2019).

Although not central to the study, sex and age-related differences were found. Sex-related differences were in full line with some previous studies (Garcia et al., 2021; Perez-Gramaje et al., 2020). Drug use was higher among males than females. Males also reported greater self-esteem, and less family and emotional self-concept than females, whereas social competence was higher among females than males. Externalizing problems during adolescence and behavioral and psychological problems were greater among males on all indicators, except in nervousness. Also age-related differences were in line with some previous studies (Alcaide et al., 2023; Garcia, Fuentes et al., 2020; Reyes et al., 2023). Adolescents reported some negative scores, for example, in self-esteem, aggression and nervousness. Interestingly, it was observed that the highest drug use was not only in adolescents, a stage related to special psychosocial vulnerability, but in adulthood, specifically among young adults. Some problems that usually begin in adolescence may continue into adulthood, such as drug use, but family experiences during the socialization years seem to have a key influence (as protective or risk factor).

Finally, this paper has strengths and limitations. The two-dimensional theoretical framework of four parenting styles used in this study is widely used throughout the world (Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Drug use and the contribution (positive or negative) of the family has also been studied for years, although this study includes the study of drugs along with a broad set of indicators of psychosocial adjustment. The new evidence is crucial because the so-called positive parenting (i.e., the authoritative style), mainly identified in studies with European-American families, may not be the most beneficial (Lamborn et al., 1991; Stephenson & Helme, 2006). However, warm but non-strict parenting (i.e., the indulgent style) is the only one that is associated with the best scores, not only with drug use, but also with psychosocial adjustment. Currently implemented psychosocial intervention strategies, mainly based on studies with European-Americans, may be ineffective or even harmful in some cases. Also, another strength of the present study is the inclusion of not only adolescent children, but also adult children.

Nevertheless, some cautions should be considered when interpreting the findings. The two-dimensional theoretical model identifies parenting styles (defined based on the two dimensions) as well as specific parental practices (defined by their degree of parental warmth and strictness) and its impact on child and adolescent developmental outcomes (see Baumrind, 1967, 1971; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Martínez-Escudero et al., 2020; Schaefer, 1959). The present study examined parental socialization through parenting styles, but not specific parenting practices (Gomez-Ortiz et al., 2018; Tur-Porcar et al., 2019) or clusters (Gomez-Ortiz et al., 2019, 2015). Some previous research has examined parenting practices such as psychological control (Barber, 1996; Schaefer, 1965), monitoring (Stattin & Kerr, 2000; Steinberg & Fletcher, 1994), or autonomy granting (Bumpus, 2001; Silk et al., 2003). Future work should examine parenting practices according to its degree of parental warmth and strictness as well as its relationship with child and adolescent developmental outcomes. The methodology of the study is non-experimental. Also, the design is cross-sectional and not longitudinal, so causal relationships associated with the passage of time cannot be established. Early experiences in adult children (in the present study, parental socialization, and problems during adolescence) have been frequently examined through cross-sectional designs, a limitation compared to longitudinal studies. Although it is a frequent strategy in the literature on adult children and is generally considered to be reliable and valid (Ali et al., 2015; Brewin et al., 1993), longitudinal designs are necessary to confirm the present findings. Finally, the data are reported in all cases by the children and not by the parents, although children seem to offer more accurate measures than parents (Barry et al., 2008; Garcia & Gracia, 2009, 2010; F. Garcia et al., 2019; Gonzales et al., 1996).

Drug use has been related to multiple protective and risk factors, one of which is the family. Traditionally, studies mainly with European-American families have identified the benefits of parental strictness (as opposed to indulgent and neglectfu homes) as a protective factor against drug use and deviant behaviors (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994). Adolescents from authoritative families, characterized by strictness in combination with warmth, are the only ones who show the highest levels of well-being and health (children from authoritarian families have internal problems such as low self-concept and self-confidence due to low parental warmth). Many of the psychosocial programs and interventions are aimed at parents (Arruabarrena et al., 2022; Sanders et al., 2022), especially when they have very young children (Linhares et al., 2022; Callejas et al., 2020), but also at adolescents (Cutrin et al., 2021). Mainly on the basis of this research with European-American families, psychosocial intervention policies and programs have been based on teaching and promoting strategies characterized by the use of parental strictness in combination with parental warmth to help educators, parents, and children (e.g., the Triple P program; see Sanders et al., 2022).

However, the widely recommended strategy based on parental strictness, according to the current study and in line with emerging studies conducted mainly in Europe and Latin America, seriously questions whether it is always beneficial (Calafat et al., 2014; Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Martinez et al., 2020; Garcia et al., 2019). The use of parental strictness to protect against drugs and related problems may be unnecessary or even detrimental, whereas warmth appears to be beneficial (children from indulgent families score as well or better than their peers from authoritative families). Parental strictness could be a risk factor for drug use and psychosocial maladjustment in some cultural contexts, especially during the period of greatest psychosocial vulnerability (adolescence), even negatively affecting the health of adults (when parental socialization has been completed). It is important to note that the so-called positive parenting (i.e., the authoritative style) could not be associated with universal benefits in all cultural contexts (Palacios et al., 2022). Future research should especially consider the cultural context to comprehensively identify protective and risk family factors based on the two-dimensional model (parental warmth and strictness) with four parenting styles.