Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is a widespread social and health problem and one of the most challenging aspects of the social and political agenda (World Health Organization [WHO, 2021]). The high global prevalence of IPV against women has increased interest in its explanatory mechanisms and consequences, with additional emphasis on the need to understand victims' help-seeking processes. Studies of victims' help-seeking behavior have highlighted the particularity of nonreported cases. Despite the number of officially registered cases, which increases every year, IPV against women continues to be systematically underreported by victims (Goodson & Hayes, 2021; Gracia, 2004, 2014; Kim & Ferraresso, 2021; Walsh & Stephenson, 2023).

Underreported IPV victimization has a direct impact on social policies aimed at prevention and intervention. Women's reluctance to report victimization to the police or to seek any kind of support (Addington & Lauritsen, 2021; Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Pérez, 2019; Packer, 2021) limits the impact of prevention and intervention initiatives as far as the scope that can be reached when women seek help and make the situation visible. It is therefore essential to develop a deeper understanding of help-seeking behavior by focusing on factors that stimulate help-seeking from formal and informal support sources.

The literature emphasizes the importance of both formal and informal sources as potential help providers. Informal help includes the victim's proximal social context (family, friends, and neighbors), while formal help involves the police, professional help, government bodies, and public services.

Formal Help-seeking: Reporting IPV to the Police

Although reporting IPV to the police tends to produce satisfactory results in IPV cases (e.g., Xie & Lynch, 2017), this resource is paradoxically underused compared to other sources of help (Goodson & Hayes, 2021). Without denying the importance of informal help, researchers argue that access to legal victim-protection and batterer-intervention programs is conditional on the victim making an official report to the police (Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Pérez, 2019; Couture-Carron et al., 2022). Researchers have shown that between 7% and 60% of IPV victims receive police support because of police notification (Augustin & Willyard, 2022). This is a broad range that other authors have tried to refine in their studies. Based on data from thirty-one countries, Goodson and Hayes (2021) showed that only 3.24% of IPV victims sought formal assistance, while a study conducted in Australia observed that fewer than one in three battered women reported an episode to the police (Stavrou et al., 2016). According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA, 2014), only 14% of women reported their partners' most serious violent incidents to the police. Lower reporting behaviors were found in other countries, with less than 8% of women in Latin America and the Caribbean reporting IPV experiences to the police (Palermo et al., 2014). These results do not offer an optimistic perspective in cases where the violence becomes chronic and even lethal. According to Bosch-Fiol and Ferrer-Pérez (2019), only 26% of women who were murdered by their partners had previously reported IPV to the police. Some underreported violent cases that end in feminicide could have been channeled through the legal system and potentially prevented.

A vast amount of literature has attempted to understand why a woman who is a victim of IPV does not go to the police to make her situation visible. It has traditionally been assumed that fear of retaliation from the batterer is the main reason why women do not report IPV to the police (Peterson et al., 2018). However, victims' fear of potential retaliation might not be the only factor that accounts for underreporting (see Sanz-Barbero et al., 2016). The severity of IPV has also been shown to be consistently related to formal help-seeking (Barrett et al., 2020; Couture-Carron et al., 2022; Goodson & Hayes, 2021; Hanson et al., 2019; Leonardsson & San Sebastian, 2017; Mehenge & Stöckl, 2021; Mengo et al., 2021). Researchers have found that victims are likely to report IPV victimization to the police or to seek other types of formal help (e.g., specialized centers) in more severe cases. Peterson et al. (2018) used the concept of a breaking point to account for this fact. According to these authors, it is only when violence reaches a certain level of severity that the victim begins to see the police as the only available option to escape victimization. The empirical literature seems to support this claim. Hanson et al. (2019) (see also Cheng et al., 2020; Cho et al., 2023) found that women tend to choose the police as help purveyors in more severe cases of IPV, suggesting that seeking help from the police reflects the desperation of the situation (Osborn & Rajah, 2020). This finding leads to the following question: “Why do most victims come to the police only when they experience severe violence?”. Another question may clarify the answer: “Could this pattern reflect victims' perceptions or definitions of IPV?”.

The extent to which women define their experiences as IPV may affect help-seeking behavior and support-source selection (Liang et al., 2005). The literature in this field has examined attitudes toward IPV, such as IPV acceptance or IPV-supporting attitudes and behaviors, to understand how women victims (and their social environment) cope with IPV situations (Gracia et al., 2020). The extent to which victims understand that specific behaviors constitute IPV is key to beginning the help-seeking process (Arboit & Mello-Padoin, 2020; Parvin et al., 2016). Researchers have empirically shown that while some women define themselves as victims, others do not, even though they suffer the same partner behaviors (García-Díaz et al., 2017). In these cases, their IPV tolerance or acceptance levels may not be the same. When tolerance toward IPV is high and this type of violent behavior is accepted as normal, the likelihood of perceiving abuse by the partner is reduced. Likewise, victims' IPV-supporting behaviors, including justification, minimization, and victim/self-blaming, affect the way victims experience and react to IPV victimization (Goodson & Hayes, 2021). These situations make them less likely to seek help. This perception of violent behaviors, which can make IPV seem acceptable, justifiable, or the fault of the victim, also impacts the perceived reportability of such behaviors, including women's awareness of the degree to which specific violent behaviors are prosecuted by the law and are thus both reportable and indictable (Martín-Fernández et al., 2018).

A survey conducted across the European Union found that 25% of female IPV victims did not report incidents to the police because they did not perceive the violent behavior as severe enough to be indictable (FRA, 2014; see also Sanz-Barbero et al., 2016; Stavrou et al., 2016). These findings suggest a link between IPV acceptance, supporting behaviors, and perceived reportability.

Ensuring that IPV behaviors are explicitly defined as reportable behaviors might be an interesting path that leads to choosing the police as a help purveyor. As a recent study has shown, better knowledge of IPV legislation among women is related to an increased likelihood that IPV victimization will be reported to the police (Kim & Ferraresso, 2021; see also Wachter et al., 2021). In addition, previous contact with formal protection systems predicts a higher likelihood of formal help-seeking within the protection system (Youstin & Siddique, 2019). These results suggest that early contact with the justice system can help women (re)define indictable behaviors more accurately and promote help-seeking from police officers, even in low-severity cases. This underlines the importance of identifying indictable IPV behaviors in the help-seeking process from police.

The Current Research

The fact that women victims of IPV might not report their victimization to the police requires further research efforts to elucidate why this occurs, especially when reporting violence to the police allows the activation of a justice system capable of protecting women and their children and preventing new episodes of IPV (Chile Atiende, 2023a, 2023b).

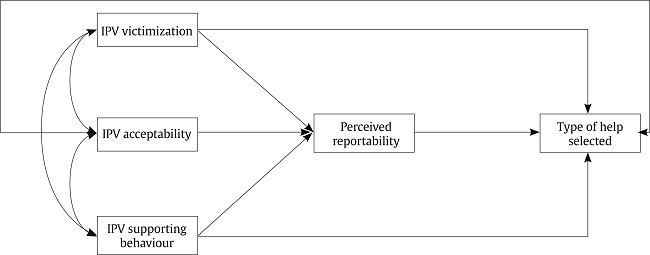

Although IPV research has thoroughly considered IPV acceptance and tolerance, IPV-supporting behaviors, and victimization severity, the extent to which IPV can be reported is misperceived (Addington & Lauritsen, 2021; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022). In our view, these concepts are intimately and sequentially related. We maintain that perceived reportability to the police in different IPV situations is the main predictor of help-seeking from the police (Figure 1). However, some antecedents may make an IPV situation perceived as more or less reportable. These antecedents include both attitudinal elements toward IPV (IPV acceptability, IPV-supporting behaviors, victim/self-blaming) and women's own experience of victimization situations. According to the literature, a positive attitude toward IPV (acceptance, tolerance, minimization, justification, etc.) may have a detrimental effect on reportability. People understand that an IPV situation is not reportable to the police if they believe that the situation occurs naturally in intimate relationships and if this leads them to not perceive the situation as particularly serious (Arboit & Mello-Padoin, 2020; García-Díaz et al., 2017; Goodson & Hayes, 2021; Liang et al., 2005; Parvin et al., 2016). Experiences of victimization, especially if they are perceived as nonsevere, may lead women to normalize the abusive situation. However, this scenario is likely to change drastically (breaking point) when the violence is perceived as severe. In this case, the likelihood of reporting the incident to the police increases (Peterson et al., 2018). However, until this breaking point is reached, increased victimization is likely to normalize the situation of violence and prevent reportability.

The general objective of this study is to empirically account for the relationship between IPV reportability and police help-seeking in a representative sample of young Chilean women. It is of particular interest to identify the antecedents that increase IPV reportability and to link this reportability to seeking help from the police. This general objective is further broken down into two specific objectives: a) to analyze the relationship between the experience of victimization, IPV acceptability, and supporting IPV behaviors on IPV reportability and b) to study the effect of reportability on the choice to seek help from the police in general and compared to other sources of available help, both informal (family, friends) and formal (psychologists, and public services). This set of relationships will be investigated in statistical models that control for the effect of both individual (socioeconomic level, educational attainment, working status) and relational (type of intimate relationship) variables.

We hypothesize that a) higher levels of victimization predict higher perceived reportability, while higher levels of acceptability and IPV-supporting behaviors predict lower perceived reportability; b) the extent to which women choose the police as help purveyors in comparison to not seeking help, seeking informal help, or seeking other formal help is predicted by the perceived reportability of IPV.

Method

Participants

This study used data from Survey No 1: “Intimate partner violence” [Sondeo N° 1: Violencia en las relaciones de pareja], conducted in 2018 by the Chilean National Institute of Youth [Instituto Nacional de la Juventud] in all 107 communities (16 regions) of Chile. A total of 1,112 Chilean men (n = 564, 50.7%) and women (n = 548, 49.3%) between 15 and 29 years were interviewed. For this study, only adult women's responses were considered (n = 510, 90.42% of the total female sample). Thirty-one participants (6%) were considered ineligible because they had never had a partner. The final study sample was therefore composed of 479 Chilean young adult women aged 18-29 (M = 23.16, SD = 3.50).

Measures

Outcome Variable

Selected Type of Help Source. The participants were asked about the type of help source they would select if they were a victim of intimate partner violence with the item “If you were a victim of some form of violence in your relationship…”. Participants were asked to choose one of the following five options: try to stay in the relationship (12.5%), seek help in the proximal context (family, friends, etc.) or informal help-seeking context (38.8%), seek help from a psychological expert (13.2%), seek help from the Chilean National Help Service for Women and Gender Equity (SERNAMEG) (14.6%), or report it to the Carabineros (Chilean police) (20.9%). The information provided by this question was statistically processed in two ways. First, the responses were grouped into a dichotomous variable: 0 = would ask for help from the police, 1 = would use other sources of help. Second, a nominal variable with five response categories was created: 0 = would ask for help from the police, 1 = stay in the relationship, 2 = informal help, 3 = psychologist, and 4 = SERNAMEG.

Covariates

Intimate-partner violent Victimization. An IPV victimization index was created by totaling the scores of five items. The items asked “Which behaviors did your partner display: (1) insulted or screamed at you, (2) humiliated or disregarded you, (3) hit, slapped, bit you, or pulled your hair, (4) humiliated or ridiculed you by spreading rumors or making fun of you on social media, or (5) shared with others or on social media pictures and/or videos containing your intimate or sexual content?”. Category responses for these items were 0 (it did not occur) and 1 (it occurred) (M = .64, SD = .98). McDonald's ω for this scale was .73.

Acceptance of Intimate-partner Violence. An index of IPV acceptance was created by totaling the scores of the following five items: How acceptable do you think the following behaviors are in an intimate relationship: (1) to insult or scream at your partner; (2) to humiliate or disregard your partner; (3) to hit, slap, pull hair, or bite your partner; (4) to humiliate or ridicule your partner by spreading rumors or making fun of him or her on social media; or (5) to share with others or on social media pictures and/or videos containing intimate or sexual content involving your partner?”. The response scale for these items was (0) unacceptable, (1) somewhat acceptable, and (2) quite acceptable (M = .34, SD = 1.62). Because of distributional limitations (92.3% of participants scored 0), the scores were transformed into a dichotomic variable to make the analysis more parsimonious: unacceptable (92.3%) and acceptable (7.7%). McDonald's ω for this scale was .96.

Intimate-partner Violence Supporting Behaviors (Justification, Minimization, and Victim Blaming). An IPV-supporting behavior index was created by adding together the scores of three items related to IPV justification (some women endorse attitudes that justify being victimized by a partner), minimization (intimate-partner violence is not severe if it does not involve rape or blows), and victim blaming (battered women like being battered; if they did not, they would leave their batterers). The responses were recoded so that higher scores represented higher IPV-supporting behavior: (1) disagree, (2) feel indifferent, and (3) agree (M = 3.56, SD = 1.07). McDonald's ω for this scale was .56.

Perceived Reportability of Intimate-partner Violence. An index of perceived IPV reportability was created by adding the scores of six items, analogous to the five items used for IPV acceptance and victimization. Participants were asked which of the following violent behaviors the victim should report to the Carabineros (Chilean police): (1) insults or screaming; (2) humiliation or disregarding; (3) pushing, hair pulling, or throwing objects; (4) hitting or physical aggression; (5) spreading rumors or making fun of a partner on social media to humiliate or ridicule him or her; or (6) sharing with others or on social media pictures and/or videos involving intimate content or sexual content. Category responses were (0) not bad enough to report to the police and (1) bad enough to report to the police. Item three for IPV acceptance and victimization was analogous to items three and four on this scale. To make the scales more congruent and easier to interpret, items three and four were recorded as one item of physical aggression: zero when the participant chose 0 for both items and 1 when the participant chose 1 for at least one item. Using this transformation, the final score was calculated based on five items analogous to the five items on acceptance and victimization (M = 4.10, SD = 1). McDonald's ω for this scale was .60.

Types of Intimate Relationships. The respondents were asked a single question about the type of relationship they had during the study (or their last relationship): “Thinking about your last intimate relationship or your current relationship, what type of intimate relationship do you or did you have?”. The original dataset distinguished five types of intimate relationships: dating someone (having dates with someone without being a couple); being part of an informal couple [pololeo]; being engaged; cohabiting with a partner; or being married. Given the small number found for some couple types, this variable was recorded by totaling the two first categories (dating someone and pololeo) into one category labeled “informal couple” (69.5%) and the last three categories (engagement, cohabiting, and marriage) into one category labeled “formal couple” (30.5%).

Sociodemographic Variables

Socioeconomic Level. Most participants were of low (39.4%, n = 189) or medium-low (27.4%, n = 131) socioeconomic status. The remaining participants were of medium-high (17.6%, n = 85) and high (15.6%, n = 75) socioeconomic status.

Educational Attainment. Educational attainment was coded using a ten-category (1-10) response scale in which higher scores represented higher levels of attainment (M = 6.94, SD = 1.69): 1 = no education (0.4%); 2 = incomplete 1st- to 7th-grade basic education (0%); 3 = complete 1st- to 7th-grade basic education (0.8%); 4 = incomplete 8th- to 12th-grade secondary education (6%); 5 = complete 8th- to 12th-grade secondary education (19%); 6 = incomplete technical education (14.6%); 7 = complete technical education (9.2%); 8 = incomplete university degree (30.8%); 9 = complete university degree (18%); and 10 = postgraduate, master's, and PhD-level studies (1.2%).

Working Status. The participants were asked to define their working status using a dichotomous response scale (yes = 48.9%, no = 51.1%) and a single question: “Do you have remunerated work?”.

Procedure

Data from a probabilistic, stratified, and two-stage (commune-household) representative sample of the young Chilean population were used for this study. The sampling framework used was the Chilean public register of phone numbers. The interviewers contacted participants by telephone using the computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) method. Using this method, 1,112 participants were selected and interviewed. The sample size was associated with an observed maximum error of ± 2.9%, assuming a maximum variance and a 95% confidence level. The data were weighted by region, sex, age, and socioeconomic level.

Data Analysis

The conceptual model in Figure 1 was empirically evaluated using two complementary structural equation models. In both models (Models 1 and 2), the relationship between the exogenous variables (victimization, acceptability, and supporting behaviors) and reportability was estimated to achieve the first specific objective: to analyze the relationship between IPV acceptability, supporting IPV behaviors, and victimization on IPV reportability. In Model 1, the focus was to test for the effect of the predictor variables on the choice to seek help from the police versus all other options. Model 1 therefore sought to estimate the likelihood of choosing the police as a help purveyor compared to all other options in general. Model 1 incorporated linear regression coefficients (for the continuous variables in the model) along with logistic regression coefficients (for the dependent variable in the model). Model 1 sought to study the relationship between levels of reportability and the intention to seek help from the police. It also allowed us to answer the following research question: Is there a general pattern in the study variables for participants who would prefer to seek help from the police (20.9% of participants) versus all other options (79.1% of participants)?

Model 2 sought to complement the results of Model 1 in that the final dependent variable had 5 response categories and thus estimated the probability of choosing the police as a source of help versus staying in the relationship, help-seeking from informal sources, help-seeking from a psychological expert, and organizational or national help-seeking for women and gender equity help-seeking (SERNAMEG). Unlike Model 1, Model 2 included four independent comparisons in terms of the profile of the participants: 1) those who would choose the police versus those who would prefer to stay in the relationship; 2) those who would choose the police versus those who would prefer informal help (family, friends, etc.); 3) those who would choose the police versus those who would prefer to go to a psychologist; and 4) those who would choose the police versus those who would prefer to go to formal public services (SERNAMEG). Model 2 also incorporated linear regression coefficients (for the continuous predictor variables) and multinomial logistic regression coefficients (for the final dependent variable). Model 2 sought to identify specific profiles of the participants that could explain the choice to seek help from the police versus each of the other forms of help-seeking that were presented to the study participants. Model 2 therefore provided complementary information on potential specific patterns in the choice of the police over each of the other options and allowed us to accomplish the second specific objective: to study the effect of reportability on the choice to seek help from the police compared to other sources of available help, both informal (family, friends) and formal (psychologists, and public services).

Model 1 and Model 2 incorporated the calculation of direct effects. To evaluate the direction and significance of the relationships estimated by the models, the unstandardized linear and logistic regression coefficients were used together with their 95% confidence intervals. The statistical package Mplus Version 8.7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2021), which allows the analysis of relationships between diverse types of variables (continuous, categorical, and nominal) in the same model, was used to estimate Model 1 and Model 2.

Results

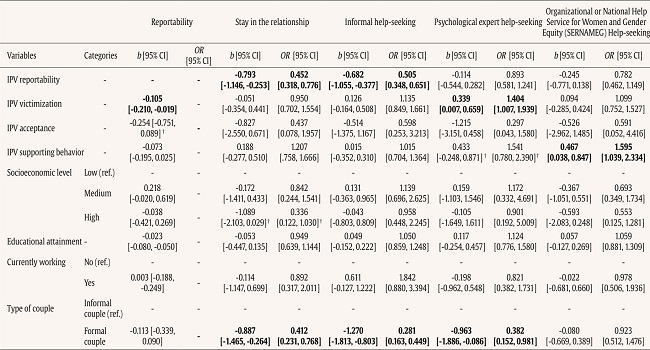

Table 1 presents the unstandardized linear and logistic regression coefficients for Model 1. The final binary dependent variable of Model 1 was 0 = would ask for help from the police and 1 = would use other sources of help. Thus, an odds ratio lower than 1 suggested a positive association with asking for help from the police, while an odds ratio greater than 1 indicated that asking for help from a source other than the police would be preferred. The statistical significance of the unstandardized estimates is given by the 95% confidence interval: if the interval does not contain the value 1, the unstandardized estimate is statistically significant at 95%. The unstandardized estimates of the linear and logistic regression coefficients (bs) are interpreted in the usual way: a significant and negative coefficient reflects a negative relationship between the predictor and the predicted variable, while a positive and significant relationship reflects a positive association between the predictor and the predicted variable.

Table 1. Unstandardized Regression Coefficients and Confidence Intervals for Predictors of Reportability and Help-seeking Behavior Type (Report to Police vs. Other).

Note.Ref. = reference category. Reference category for comparisons: Report to carabineros (Chilean police).

† =p ≤ .10.

Predictors of Perceived Reportability

IPV victimization (b = -0.10, p < .05) was significantly and negatively associated with perceived reportability. The higher the level of IPV victimization, the lower the perceived reportability. IPV acceptance showed a marginal and negative relationship (b = -0.27 p < .10) with perceived reportability, suggesting that the higher the acceptability of IPV, the lower its perceived reportability. IPV-supporting behaviors did not show a significant relationship with perceived reportability (b = -0.07, ns). Perceived reportability was not statistically related to sociodemographic variables (socioeconomic level, educational attainment, work status) or relational variables (formal vs. informal couple).

Seeking Help from Police

Perceived reportability showed a negative and significant relationship with the final dependent variable (b = -0.53, p < .05). Higher values of this variable (higher level of perceived reportability) were statistically related to lower values of the dependent variable (0 = seeking help from police). None of the predictors of perceived reportability showed a significant direct relationship with seeking help from the police. However, we found a tendency for formal couples to seek help from the police more than from other sources of help (b = -0.87, p < .05) compared to informal couples. This result suggests that regardless of perceived reportability, maintaining a formal relationship is associated with seeking help from the police in IPV cases.

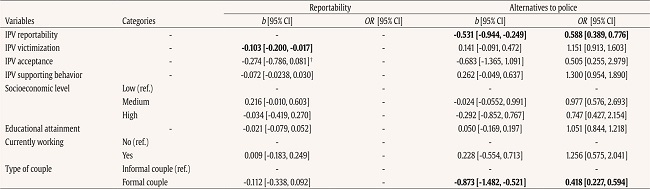

Model 2 replicates part of Model 1 (the prediction of perceived reportability) but differs from Model 1 by using reportability to predict the specific choice of the police versus each of the other options: staying in the relationship, informal help, and two types of formal help (professional psychological help and use of public help services - SERNAMEG). To do so, it assigns category 0 to the choice to seek help from the police and category 1 to each of the remaining choices in the four comparisons.

Predictors of Perceived Reportability

The results of Model 2 for the prediction of perceived reportability are equivalent to those found for Model 1, with minor differences in the coefficients due to sample reduction. This is because, in Model 2, smaller groups were compared (for example, choosing the police versus choosing to stay with a partner), which could marginally affect the size of the coefficients. In any case, the direction and statistical significance of the relationships were the same as those of Model 1. Thus, IPV victimization (b = -0.10, p < .05) was significantly and negatively associated with perceived reportability, and IPV acceptance showed a marginal and negative relationship (b = -0.25 p < .10) with perceived reportability. IPV-supporting behaviors did not show a significant relationship with perceived reportability (b = -0.07, ns). Perceived reportability did not show a statistical relationship with sociodemographic (socioeconomic level, educational attainment, work status) or relational variables (formal vs. informal couple).

Seeking Help from Police vs. Each of the Other Sources of Help

- Comparison 1. Seeking help from police vs. staying in the relationship. Perceived reportability was significantly associated with seeking help from the police vs. staying in the relationship (b = -0.79, p < .05). Thus, higher scores for perceived reportability were statistically associated with lower scores for the outcome variable (0 = seeking help from the police, 1 = staying in the relationship). Formal couples showed a tendency to seek help from the police more than staying in the relationship (b = -0.89, p < .05). We did not find a statistical relationship for the remaining sociodemographic variables.

- Comparison 2. Seeking help from police vs. informal help-seeking. Perceived reportability was significantly associated with seeking help from the police vs. seeking informal help (b = -0.68, p < .05). Again, formal couples showed a tendency to seek help from the police more than informal help (b = -1.21, p < .05). No other statistical relationship for the remaining sociodemographic variables was found. 3.

- Comparison 3. Seeking help from the police vs. formal help-seeking: professional psychologist. In this specific case of comparison between two types of formal help (police vs. psychologist) perceived reportability did not seem to play a relevant role (b = -0.11, ns). Although there was a tendency for high scores in perceived reportability to be related to the choice of police, this relationship was far from statistically significant. In this specific case, we observed a direct relationship between one of the predictors of perceived reportability—IPV victimization—and the choice of the police as a source of help: higher scores for IPV victimization were associated with a preference for seeking help from a psychologist rather than the police (b = 0.34, p < .05). Additionally, IPV-supporting behaviors showed a marginal and positive effect on choosing to seek help from a psychologist rather than seeking help from the police (b = 0.43, p < .10). Formal couples continued to show a tendency to prefer the police over psychologists (b = -0.96, p < .05). 4.

- Comparison 4. Seeking help from the police vs. formal help-seeking: public services (SERNAMEG). When the choice of the police was compared against the public service of SERNAMEG, a direct effect of IPV-supporting behaviors on the choice of the source of help (b = 0.47, p <.05) was found. Thus, there seems to be a statistical trend in which IPV-supporting behaviors encourage the use of public help services instead of going to the police. In this specific case of comparing two types of formal help (police vs. public help services), the type of couple does not seem to have an effect (Table 2).

Discussion

Using the data of 479 Chilean young adult women from Survey No 1, “Intimate partner violence” [Sondeo N° 1: Violencia en las relaciones de pareja] conducted by the INJUV (2018), this study analyzed the relevance of perceived IPV reportability on women's choice of the police as help purveyors.

As a first objective, we explored the roles of IPV victimization, IPV acceptability, and IPV-supporting behaviors in perceived reportability, but the hypothesized relationships were not fully confirmed. First, the estimated models suggested that victimization experience was a relevant marker of reportability: the higher the level of IPV victimization, the lower its perceived reportability to the police. Second, IPV acceptance had a marginal influence on reportability, and IPV-supporting behaviors did not influence perceived reportability.

These results seem to partially contradict the breaking point hypothesis (Peterson et al., 2018), whereby when victimization reaches a certain level of severity the victim begins to see the police as the only available option to escape victimization. According to this hypothesis, participants with more severe experiences of IPV victimization should show a greater inclination to report to the police. It was found that those who experienced victimization tended to perceive IPV situations as less reportable to the police than those who did not experience such situations. These results do not necessarily contradict Peterson et al.'s (2018) breaking point hypothesis since it is unlikely that severe cases of IPV were experienced among the participants in this study. The mean of IPV victimization among the participants was very low (0.64 out of a range of 0 to 5). In situations of low-severity IPV exposure, participants tend not to perceive IPV as reportable to the police. This has the interesting effect that in social systems where low-intensity IPV is widespread members of the social system tend to normalize such abusive situations and incorporate them into the couple's relational practices, even in the extreme case that such practices are typified as an offense in their legal systems (Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2019).

These results suggest that reportability is primarily influenced by the victimization experience of the participants and that attitudes toward IPV seem to play a secondary role. Nevertheless, as mentioned, the higher the experienced level of IPV victimization, the less likely participants are to perceive the police as a potential source of help. Based on previous studies that have pointed out the relationship between IPV victimization and formal help-seeking (Goodson & Hayes, 2021; Hanson et al., 2019), it is reasonable to expect victimized women to perceive more indictable IPV behaviors as the frequency and severity of these behaviors increase in line with the tendency to seek formal help as the frequency and severity of victimization increase (Goodson & Hayes, 2021; Hanson et al., 2019; Peterson et al., 2018).

The previous analysis is congruent with the marginal association found between IPV acceptability and perceived reportability: the higher the IPV acceptance, the lower its perceived reportability. It is tenable that people understand that an IPV situation is not reportable to the police if they accept that this situation occurs naturally in intimate relationships (Arboit & Mello-Padoin, 2020; García-Díaz et al., 2017; Goodson & Hayes, 2021; Liang et al., 2005; Parvin et al., 2016). Our data empirically support that claim while assuming lower confidence levels.

In this study we also explored the relationship between levels of reportability and the intention to seek help from the police and studied the effect of reportability on the choice to seek help from the police compared to other sources of available help, both informal (family, friends) and formal (psychologists and public services). The first of these objectives sought to empirically explore the relationship between reportability to the police and potential help-seeking from them. Our research hypothesis was that the perception of the police as a source of help would occur mainly when situations were perceived as worthy of being brought to the attention of the police authorities. Our results confirm this hypothesis: the higher the level of reportability among participants, the greater the frequency with which they choose the police as a source of help over all other options. To the extent that a victim's help-seeking process is based on (1) defining or recognizing IPV as a problem, (2) making the decision to seek help, and (3) selecting the source of help (Liang et al., 2005), defining IPV as violence and typifying the situation as an offense in the legal system does not seem to be sufficient to mobilize help-seeking from the police. It is also necessary for citizens to perceive that a situation should be reported to the police. This is precisely what was found in our models: participants will seek help from the police if they perceive that IPV situations are reportable; otherwise, they will not. In this case, better knowledge of IPV legislation among women increases the likelihood that IPV will be reported to the police (Kim & Ferraresso, 2021; see also Wachter et al., 2021) and enables the activation of a system of legal assistance and protection for victims (Youstin & Siddique, 2019). It is therefore plausible that the lack of legal knowledge directly affects the definition of IPV as indictable. Thus, victims' attempts to report IPV victimization are hindered by their lack of knowledge of IPV-related legislation, which in turn implies a failure to define indictable behaviors as reportable to the police even when victims are willing to report them. Following the recommendations of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (2018), in their concluding observations on the seventh periodic report on Chile, women's access to IPV-related legal information should be ensured to facilitate links between IPV-AW victims and the justice system.

We further conducted a point-by-point comparison of the effect of reportability in the choice of the police as a source of help versus 1) staying in the relationship, 2) seeking help from family and friends, 3) seeking professional formal help (psychologist), and 4) seeking another type of formal help in public services (SERNAMEG in the case of Chile).

When the relationship between perceived reportability and help-seeking is evaluated with a greater degree of specificity, interesting nuances appear in addition to what was previously found in Model 1. In general, as we move from not seeking help (staying in the relationship) and seeking informal help (turning to family and friends) to seeking formal help (psychologists, public services—SERNAMEG), the role of reportability is reduced. The highest levels of reportability are associated with seeking help from the police versus the choice of staying in the relationship (i.e., letting things take their course) and the option of seeking help from family and friends (i.e., using the proximal social context to try to solve the problem). When the choice is between two types of formal help, the role of reportability as an important predictor of seeking help from the police disappears. Thus, reportability does not seem to influence the decision to seek help from the police or psychologists, nor does it influence the choice of the police as a source of help and other formal public services such as SERNAMEG in Chile. According to the results obtained in Model 2, the choice between formal services is marked by the experience of victimization and IPV-supporting behaviors depending on the help purveyor. When victimization levels are higher and women endorse IPV-supporting behaviors, there is a tendency to prefer psychologists over the police as a source of help. When women endorse more IPV-supporting behaviors, they tend to prefer public services such as SERNAMEG instead of the police. According to these results, IPV-supporting behaviors play a key role in the selection of the type of formal assistance that is requested, specifically, moving away from the police in favor of other types of formal help (psychologists and public services).

In the case of the choice of police versus the use of public services (SERNAMEG), women who endorse IPV-supporting behaviors justify IPV, minimize IPV, and blame the victims for the IPV they have suffered prefer to make the situation visible to public services rather than go to the police. These results also confirm earlier research showing that victims tend to minimize the IPV they have suffered and believe that it is not severe enough to report to the police (FRA, 2014). They justify violent behavior by defining it as ‘reasonable' based on various circumstances (Goodnes & Hayes, 2021; Mengo et al., 2021) or even consider it a victim-provoked response and blame the victim (Goodnes & Hayes, 2021; Overstreet & Quinn, 2013).

The results of Model 2 also highlighted the importance of relational aspects in the help-seeking decision. In three of the four comparisons, relationship commitment (more formal and stable relationships) was shown to be a significant marker of help-seeking from the police. Participants involved in more stable relationships preferred to go to the police for help versus staying in the relationship, seeking informal help from friends and family, or going to a psychologist. In contrast to previous research comparing the help-seeking behavior of married women to that of unmarried women (see Hu et al., 2021; Linos et al., 2014; Parvin et al., 2016), the present results suggest that women in stable relationships are more likely to report IPV to the police. More stable relationships are also expected to be longer relationships in which the likelihood of confronting conflictive couple situations is higher and IPV is likely to occur more often (Cooper et al., 2020; Juarros-Basterretxea, Ocampo, et al., 2022; Kennedy et al., 2018; Lafontaine et al., 2020; Swiatlo et al., 2020). In this regard, the likelihood that women in more stable relationships will seek police help may be related to the larger history of victimization rather than to its severity; this can be considered another way to reach the breaking point, as previously documented in more severe cases (Peterson et al., 2018). Accordingly, the breaking point can also be explained by factors related to relationship length and thus to the longer history of victimization (Juarros-Basterretxea, Ocampo, et al., 2022). In longer relationships with a more extensive history of victimization, women have probably already tried other types of support; when they are unsuccessful, they report the violence to the police as a final and desperate measure. Being married for more years is also a predisposing factor for IPV help-seeking (Leonardsson & San Sebastian, 2017). Greater exposure to IPV makes it more likely that people in the proximal social context of the victim will detect the violence. Their reactions can raise the IPV awareness of the victimized woman (Barrett et al., 2020; Shin & Park, 2021). This interesting result is also found in the comparison between seeking help from police officers and psychological expert help, another form of formal help-seeking. This finding supports the explanation that women in long-term relationships that involve longer exposure to IPV look for more formal help.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has several strengths and potential limitations. The first strength lies in the fact that the participants belonged to a representative sample of the young Chilean population, making both the findings and the conclusions generalizable. Second, an integral analysis of help-seeking behavior follows ecological approximations. In this regard, the current research follows recent recommendations for IPV analysis, including a range of factors and the multidimensional nature of the phenomena (Hammock et al., 2017; Herrero et al., 2020; Juarros-Basterretxea, Herrero, et al., 2022; Juarros-Basterretxea, Ocampo, et al., 2022; Osborn & Rajah, 2020). A third strength of the present study is its ability to advance research on the effect of perceived reportability on the potential selection of various sources of help, from more informal to more formal. Research in this field has traditionally focused on understanding what factors predispose IPV victims to choose the police as a potential source of help. However, it has rarely been considered that each source of help has specific antecedents, as we have shown in this study. The choice of the police as a potential source of help shares predictors with other sources of formal support (psychologists or public services) versus other informal sources (family and friends). However, it differs from other forms of formal support in some interesting aspects, such as the importance of attitudinal variables, victimization experience, and relationship characteristics (informal vs. formal).

In terms of limitations, it is important to note that although survey data have the advantage of facilitating representative samples, they come at the expense of using more simplified variable questionnaires. The low internal consistency found for some of the scales in the study may have been influenced by this circumstance. Also, the use of categorical responses is common, which limits the power of the analysis. Future research should prioritize the use of continuous variables and the inclusion of other validated questionnaires. In addition, despite the multidimensional nature of the help-seeking process, other factors not assessed in the current research may underlie the tendency to seek help from formal sources other than the police. Future research should therefore include other factors, such as trust in the criminal justice system (Fedina et al., 2019; INJUV, 2018) and women's resilience (Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022).

Conclusion

The way women and society define IPV as a problem is key to understanding why women seek formal help by reporting IPV to the police instead of staying in their relationships or seeking informal help only. Future intervention and prevention programs should aim to make women more aware of indictable behaviors that can be reported to the police. Similarly, the great efforts made to address the effect of IPV victimization and the impact of IPV-supporting attitudes (including justification, minimization, and victim blaming) on women's help-seeking processes must be strengthened in favor of choosing the police as a help purveyor in IPV-AW cases rather than other formal help sources. Efforts to increase knowledge of the criminal justice system and available legal resources among women and the community, in general, are key factors in making meaningful changes in the formal help-seeking processes of IPV-AW victims.

The underreportability of intimate partner violence suffered by women has attracted researchers' attention in recent decades. It is generally accepted that if cases of IPV against women are not made visible to the authorities (judicial system, police, etc.), intervention initiatives are significantly and negatively affected. In this study, we addressed some of the main antecedents that allow us to understand the circumstances in which the probability of reporting IPV to the police decreases. The answer we have found is far from simple: the perceived reportability of IPV improves the likelihood of going to the police for help compared to some alternatives (informal help) but not others (formal help). In addition, the type of couple (informal vs. informal) appears to exert a significant effect on the choice of the police as a source of help. Study participants with more formal relationships (cohabiting or married, for example) were more likely to seek help from the police in the event of IPV. Alternatively, participants in less stable or more informal relationships (dating, short-term relationships, etc.) were less likely to report potential IPV to the police. In sum, our results reflect the complexity inherent in women's visibility of their IPV victimization to the police and illustrate the need for further study of their experiential (IPV victimization) and attitudinal (acceptability of and support for IPV behaviors) antecedents.