INTRODUCTION

Imagery is a set of techniques used among athletes that entails the mental rehearsal of a motor skill (Callow, Jiang, Roberts, & Edwards, 2016; Filgueiras, 2016a; Filgueiras & Hall, 2017; Hall, Rodgers, & Barr, 1990; Holmes & Collins, 2001; Paivio, 1985). There are theoretical (Hall & Martin, 1997; Paivio, 1985) and applied models (Holmes & Collins, 2001; Wakefield, Smith, Moran, & Holmes, 2013) to organize how an image should be created in mind. Well-conducted sport-related imagery allows: to improve skill performance (Callow et al., 2016; Filgueiras, 2016a), to enable emotional management (Roure et al., 1998; Vadoa, Hall, & Moritz, 1997), to increase intrinsic motivation (Callow, Hardy, & Hall, 2001; Paivio, 1985) and to facilitate motor learning (Lebon, Collet, & Guillot, 2010; Nobuaki Mizuguchi, Nakata, Uchida, & Kanosue, 2012; Moran, Guillot, MacIntyre, & Collet, 2012).

Paivio's (1985) theoretical model was extensively studied throughout the last thirty years and showed good empirical evidence of validity. It is a five-factor model that divides imagery in sport according to emotional and cognitive dimensions (Filgueiras, 2016b; M. Gregg, Hall, McGowan, & Hall, 2011; Melanie Gregg, Hall, & Nederhof, 2005; Hall, Mack, Paivio, & Hausenblas, 1998; Hall et al., 1990). There are two cognitive factors: Cognitive Specific (CS) relates to technical and movement perfection imagery and Cognitive General (CG) entails tactical, strategic and planning imagery (Hall et al., 1998; Paivio, 1985). The other three factors are associated with motivation and emotion: Motivational Specific (MS) involves imagery of winning and achieving goals, Motivational General-Arousal (MG-A) represents images of the emotional arousal (i.e., anxiety, excitement, etc.) related to competing, and Motivational General-Mastery (MG-M) relates to manage and control of emotions during competitions. These five factors were assessed through factor analysis in papers from different countries and it showed same dimensionality in Canadian (Hall et al., 1998), Finnish (Watt, Jaakola, & Morris, 2006), Brazilian (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017), Spanish (Ruiz & Watt, 2014) and Turkish samples (Vurgun, Dorak, & Ozsaker, 2012). It suggests that factorial validity is stable across cultures and imagery can be theoretically observed from Paivio's (1985) approach.

Imagery use seems to differ among athletes (Hall et al., 1990). Despite of being a simple set of techniques and recommended by sport psychologists (Callow et al., 2016; N. Mizuguchi, Nakata, & Kanosue, 2016), evidence suggests that individual differences (Balser et al., 2014; Filgueiras, 2016a; Seiler, Monsma, & Newman-Norlund, 2015; Wei & Luo, 2010) and types of sports (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017; Ruiz & Watt, 2014; Wriessnegger, Steyrl, Koschutnig, & Müller-Putz, 2014) may play a role in the way individuals use imagery in sports.

Balser et al. (2014) researched how expertise influences the way athletes predict through imagery observed actions related to their sport; results showed that experience enhances imagery and changes neural circuits related to motor skills. Same results in neuroimaging were found by Wei and Luo (2010) in motor imagery tasks by comparing normal participants with elite sportspersons. Seiler, Monsma and Newman-Norlund (2015) showed how non-athletes also show individual differences of neural pathway organization in imagery tasks. Behaviorally, the presence of a sport psychologist working with an athlete can improve imagery use (Filgueiras, 2016a), as well as level of practice (i.e., amateur vs. elite) and time of imagery practice (M. Gregg et al., 2011; Hall et al., 1990).

On the other hand, evidence suggests that athletes from different types of sport perhaps use imagery differently. For example, Ruiz and Watt (2014) found out that combat sport fighters tend to use CS and CG imagery more frequently when compared to other sport categories, whereas invasion contact ballgames (e.g., football, basketball, handball and polo) use significantly more MS than cyclists (Ruiz & Watt, 2014). Similar evidence was found by Filgueiras and Hall (2017) who presented results depicting significantly higher CG imagery use among beach volleyball players than gymnastics. Also, combat sportspersons showed MS imagery use more frequently than football, gymnastics and basketball, whereas MG-A use was found to be statistically more common among combat sport athletes than beach volleyball players (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017).

In a recent study, Campos, López-Araújo and Pérez-Fabello (2016) compared individuals who exercised through sport practices (i.e., indoor football and basketball) and other physical activities (i.e.; ballroom dancing and pilates). They found differences between groups regarding the use of spatial and verbal imagery: individuals who practiced pilates showed higher use of verbal imagery, whereas individuals who practice group sports tend to use spatial imagery more frequently (Campos, López-Araújo, & Pérez-Fabello, 2016). Accordingly, Wriessnegger et al. (2014) showed that practicing a type of sport could boost motor imagery regarding those specific skills, but no generalization. It means that practicing one skill leads to imagery facilitation of that specific skill and no other.

Sport practices and choice of category seem to have influence from psychological variables. There is evidence suggesting that some types of sport show higher prevalence of eating and anxiety disorders than others (Schaal et al., 2011). The profile of athlete's five-factor personality predicts sport choice (Magnusen, Kim, Perrewé, & Ferris, 2014) and athletes with higher traits of anxiety tend to choose types of sport less vigorous and with less contact (Newcombe & Boyle, 1995). The separation of sports in levels of contact seems to make sense, since personality traits are able to predict sport choice and preference (Rice, 2008). If psychological variables influence sport choice, practice and preference, one can hypothesize that imagery use is mediated by sport category. However, athletes' psychological dimensions differ within the same type of sport, as well as imagery use, so individual differences appear as the most cited and referred explanation for frequency of imagery use among athletes (Filgueiras, 2016a; M. Gregg et al., 2011; Melanie Gregg et al., 2005; Hall et al., 1990).

There is no unanimity regarding imagery use in the literature. Although it seems clear that individual differences and sport categories indeed play roles in imagery use, there are few researches addressing this specific question (Campos et al., 2016; M. Gregg et al., 2011; Hall et al., 1990). In fact, researchers tend to explain frequency of imagery use based on individual differences (Filgueiras, 2016a; M. J. Gregg & Hall, 2016; Seiler et al., 2015; Wei & Luo, 2010) rather than types of sport (Campos et al., 2016; Filgueiras & Hall, 2017; Ruiz & Watt, 2014; Wriessnegger et al., 2014). The relevance of this issue lies on the strategies adopted by sport psychologists and other practitioners whenever building their imagery program. To understand the differences between types of sports regarding imagery use can be helpful for professionals to develop sport-specific imagery training. The aim of the present study is to analyze empirical evidence of imagery use among athletes to understand the differences between groups of distinct types of sport.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

The participants of the present study (N=199) were elite athletes recruited through e-mail after the main researcher made contact to their respective sport Federation. Volunteers were from Football (N=114; 83.3% men), Taekwondo (N=12; 100% men), Jiu-Jitsu (N=9; 100% men) and Northern Shaolin Kung Fu (N=64; 89.1% men). Athletes were considered elite if they trained at least four times a week for the minimum of two hours a day (all participants), and competed in national (N=138; 69.3%) or international (N=61; 30.7%) levels. Sport categories were classified according to Rice (2008) in Full-contact sports (i.e., sports that require physical contact almost the whole time: Taekwondo, Jiu-Jitsu and Northern Shaolin Kung Fu) and Limited contact sports (i.e., physical contact is not required, can lead to a foul, but may happen in specific circumstances: Football).

Instruments

Demographic questionnaire: A simple questionnaire that asked demographic variables and sport characteristics, such as: age, time of practice of this specific sport (in years), education (in years), if they had participation in national or international competitions in the current or last years, if they had a sport psychologist working for them, and number of hours of training per week

Sport Imagery Questionnaire (Hall et al., 1998): The Brazilian-adapted version of the Sport Imagery Questionnaire: SIQ-BR (Filgueiras, 2016b; Filgueiras & Hall, 2017) is a 30-item test divided in five factors (six items per factor) that assesses the frequency of imagery use. The instrument was developed to use a Likert-type scale ranging from “1-never/rarely” to “7-often” according to Paivio's (1985) five-factor model: Cognitive Specific (CS), Cognitive General (CG), Motivational Specific: Arousal (MG-A), Motivational General: Mastery (MG-M) and Motivational Specific (MS)(Hall et al., 1998). Examples of items are: “I can consistently control the image of physical skill” (CS), “I make up new strategies in my head” (CG), “I image myself to be focused during a challenging situation” (MG-M), “I image myself handling the stress and excitement of competitions and remaining calm” (MG-A), and “I image myself winning a medal” (MS). Psychometric properties of the Brazilian-adapted version of SIQ were satisfactory (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017). The study showed good internal consistency using Crobach's alpha as reference, ranging from 0.87 to 0.94. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses confirmed the five-factor structure, whereas construct validity showed low-to-moderate correlation between factors.

Procedure

Each participant was contacted through e-mail provided by their own Federation. They were asked to visit the laboratory website where a pop-up window lead them to the Consent Form. After reading and agreeing with participation, another webpage opened with one demographic questionnaire and one instrument. The questionnaire asked the volunteer simple demographic questions. The instrument was the Sport Imagery Questionnaire (Hall et al., 1998) in its Brazilian version (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017). After completing the demographic questionnaire and SIQ-BR, a thank you page opened to participants. All procedures were authorized by Rio de Janeiro State University Ethical Committee.

Statistical Analysis

The first step was to describe categorical data (participation in national or international competitions, and presence of a sport psychologist) using frequency (N) and percentage (%). Continuous data was described using arithmetic mean and standard deviation (SD).

In order to answer the question raised in the objective of this article, a Canonical Discriminant Analysis (CDA) was performed. This statistical procedure finds patterns of canonical correlation between features that separates scores and items (i.e., demographics and SIQ-BR scores) according to a dependent variable (Full-contact vs. Limited contact sports). In other words, CDA is a type of regression that allows identification of which items or instruments are better than others to separate subjects (individual differences) and groups (types of sport). Three statistics are considered to understand CDA results: chi-square (χ2), Wilk's lambda (λ), and Standardized Canonical Coefficient (SCC). The χ2 statistic reveals whether the variable is able to discriminate groups in a significant manner (p < 0.05). Because CDA was used in the present study through stepwise method, only significant variables are included in the regression. Wilk's λ tests the extent to which a variable contributes to discrimination within group: the closer to λ=0, the higher the extent to which the variable contributes to separate individuals. The SCC ranks the importance of variables to separate groups; in other words, the higher the coefficient, the more this variable separates groups.

The difference between SCC and Wilk's λ are due: SCC accounts for the variable that separates sport categories; on the other, Wilk's λ reveals the extent this separation is caused by the amount of individuals in the sample, thus necessarily associated to the whole set of participants. It means that, the highest SCC represents the variable that discriminates better the participants according to their types of sport, whereas the lowest Wilk's λ reveals the variable that separates the most within the whole set of participants. All analyses were performed in SPSS 20.0.

RESULTS

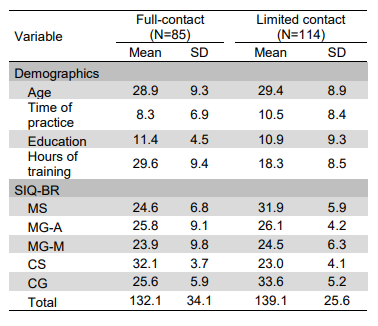

Categorical variables showed that most participants compete nationally (N=138; 69.3%) rather than internationally (N=61; 30.7%). Among Full-contact athletes (N=85; 42.7%), only 12 (14.1%) competed internationally, whereas 73 (85.9%) competed nationally. Among Limited contact athletes (N=114; 57.3%), 49 (43.0%) competed at international level, and 65 (57.0%) only competed at national level. In addition, fewer participants (N=23; 11.6%) had a sport psychologist working for them when compared to those who had not (N=176; 88.4%). In fact, among those who had a sport psychologist, only 6 (26.1%) were Full-contact athletes, compared to 17 (73.9%) Limited contact volunteers. Table 1 depicts descriptive statistics of continuous data.

Table 1. Demographic and SIQ-BR descriptive statistics.

Note:Age, Time of practice and Education are measured in years. Hours of trainning entails number of hours per week. SIQ-BR refers to the Brazilian Version of the Sport Imagery Questionnaire, whereas MS: Motivational Specific, MG-A: Motivational General - Arousal, MG-M: Motivational General - Mastery, CS: Cognitive Specific, and CG: Cognitive General.

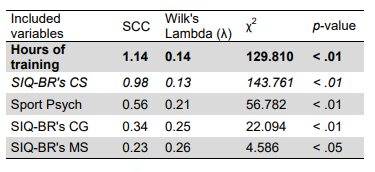

The CDA revealed that five variables were able to discriminate and separate types of sports: number of hours of training per week, presence (or absence) of a sport psychologist working for the athlete, and SIQ-BR scores for CS, CG and MS imagery. It means that there was no significant discrimination between types of sport according to: age, time of practice, education, level of competition (national vs. international), SIQ-BR total score, MG-A and MG-M scores. Table 2 shows statistics of CDA for inserted variables according to stepwise method.

Table 2. Results of the Canonical Discriminant Analysis.

Note:SCC = Standardized Canonical Coefficiente, Hours of trainning = number of hours of skill (technical or tactical) trainning per week. SIQ-BR = Sport Imagery Questionnaire - Brazil, CS = Cognitive Specific, CG = Cognitive General, MS = Motivational Specific. Sport Psych entails the presence or absence of a Sport Psychologist working for the athlete.

Bold:Highest SCC = most discriminative variable between groups.

ItalicLowest Wilk's λ = most discriminative variable within group. Excluded variables in stepwise method: Age, Time of practice, Education, Level of competition, SIQ-BR's MG-M, MG-A and SIQ-BR total score.

Hours of training had the highest SCC, which entails that Full-contact athletes train more than Limited contact athletes. However, to separate those who use a few to those who use a lot of imagery, SIQ-BR's CS presented the lowest Wilk's λ; thus, Full-contact athletes tend to use more CS and those who use it, do it more than other participants of the same type of sport. The other three variables able to discriminate types of sport, the presence or absence of a sport psychologist seem to be pivotal, as Limited contact sport has more of those professionals than Full-contact sports. Finally, CG and MS imagery were also discriminant between groups. Results suggest that Limited contact sport shows higher frequency of CG and MS imagery use than Full-contact athletes do.

DISCUSSION

Results of the present article revealed that imagery use differ in types of sport, which corroborates with previous evidence (Campos et al., 2016; Filgueiras & Hall, 2017; Ruiz & Watt, 2014). Although other variables also revealed to be discriminative between sport categories, three of the five factors of Paivio's (1985) model measured by SIQ-BR (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017; Hall et al., 1998) were able to separate participants of distinct types of sport.

Regarding demographics, it was expected to see no statistical difference between Full-contact and Limited contact sports (Newcombe & Boyle, 1995). In fact, the only Limited contact sport studied by this paper was Football, it is a pivotal limitation of the present research and comparison to other sports within the same category should be addressed in future studies. Despite of that, Full-contact elite athletes seem to have more time training every day when compared to professional footballers; even though, these last have more psychological support through sport psychologists than the first. Perhaps it could be partially explained by sport routine and way of practice: Full-contact sport is more vigorous and require individual attention, whereas, Football is a team sport and responsibility is shared among peers (Rice, 2008).

Specifically about imagery, CS appears significantly higher among Full-contact athletes and discriminates better than all other imagery factors. Probably, specificities of this type of sport such as risk of injury (Rice, 2008), need of discipline and style of training combined with the high demand of perfectionism make athletes to produce higher amounts of technical image, whereas, Football is less demanding on those aspects. Accordingly, combat-sports, a subtype of Full-contact sports, already showed significantly higher CS use when compared to other categories, which agrees with the present results (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017; Ruiz & Watt, 2014). It seems that combat athletes tend to use CS imagery more frequently than other sports; however, the question why does it happen remain unanswered. The arguments given above are purely speculative; it was more an attempt to build a hypothesis than give an explanation for this phenomenon.

On the opposite side, Football elite athletes presented more MS and CG imagery use than Full-contact athletes did. Even though the ability of those two factors to discriminate individuals of the two groups were low when compared to CS, they still able to separate. These results are partially the opposite of those found by Filgueiras and Hall (2017); combat-sport athletes presented higher MS imagery use than footballers did. One possible explanation for this phenomenon was the sport itself: the participants of the present research were Taekwondo, Jiu-Jitsu and Northern Shaolin Kung Fu fighters, whereas, Filgueiras and Hall (2017) did not presented information regarding the specific category of combat sport they had in their sample. Perhaps, imagery use also differ among combat sports, however, with the current sample and in the present study, it is not possible to test this hypothesis.

Ruiz and Watt (2014) showed evidence suggesting that combat sport athletes show higher CG imagery use than gymnastic athletes do. Filgueiras and Hall (2017) did not find any difference regarding CG use between Football and combat-sports. The present study revealed that footballers actually present more CG imagery use than Full-contact athletes do, what was not found previously in the literature. There is no clear explanation on why it happened, however, researchers might speculate that the number of possibilities and tactical demands in Football is higher than in Full-contact sports, even though, this explanation is merely hypothetical.

Another explanation for why footballers seem to have larger imagery use in CG and MS is the significantly larger presence of sport psychologists working for them. Although SIQ-BR total score was not able to discriminate groups, the literature suggests that sport psychologists tend to adopt imagery as a technique to help athletes (Filgueiras, 2016a; Hall et al., 1990; Holmes & Collins, 2001; Paivio, 1985), so it is possible that those professionals lead footballers to increase use of imagery in those two factors.

In conclusion, results of the present research provide evidence that imagery use is indeed different between types of sport (Filgueiras & Hall, 2017; Ruiz & Watt, 2014; Wriessnegger et al., 2014). It does not exclude the importance of individual differences and expertise in a sport category (Balser et al., 2014; Filgueiras, 2016a; Seiler et al., 2015; Wei & Luo, 2010), but adds another layer to this discussion. Sport psychologists might benefit from this information, because it seems that they need to work harder to increase frequency of imagery use of those factors that are not imaged by athletes of different sports.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

There were four clear limitations of the study and they should be considered when results are generalized. The first issue was the small sample size, even though elite athletes are quite a difficult sample to collect data, perhaps more participants would increase the ability of this study to make more precise predictions. The second problem is the concentration of the number of sport psychologists in one of the two groups. It creates a confound variable, because it is not clear whether the results could be mediated by the presence of a professional practitioner. Perhaps future studies would benefit with cross-analyses considering presence or absence of a professional help.

The third issue that can be raised is the lack of other types of sports in the Limited Contact category. Only football was assessed and, perhaps, it can show significant differences to other types of sports even within the same classification. The fourth and final issue was the lack of an analysis modeling the mediation of variables, in order to do that, a Structural Equation Modeling would be recommended, however the small sample size within each classification of sports did not allow this analysis. Future studies with other sport categories and bigger sample are needed to ensure the hypothesis of imagery use differences between types of sports.