INTRODUCCIÓN

The world is experimenting unprecedented changes as result of the COVID19 pandemic (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2020). Many countries around the world imposed strict lockdowns of their population to protect citizens from virus transmission (Kumar et al., 2020; Sánchez-Caballero et al., 2020). In Spain, the government imposed the 'state of alarm' on 15th March 2020 (Gobierno de España, 2020), requiring citizens to observe a very strict lockdown for 71 days. These extreme lockdown measures imposed unprecedented restrictions on physical activity (PA) and sport practice on Spanish citizens, with encompassing lifestyle consequences (Camacho-Cardeñosa et al., 2020).

Problems derived from lockdown

A prolonged lockdown of the population might present negative consequences for health due to the onset of new diseases or the increase of pre-existing conditions. Several studies have argued that one of the likely consequences of lockdown is to adopt an unhealthy lifestyle due to the reduction of physical activity (Di Sebastiano et al., 2020), which can contribute to the development of negative cardiovascular or psychological conditions (Bhutani & Cooper, 2020; Mattioli & Ballerini, 2020; Pechaña et al., 2020).

Lippi et al. (2020) pointed out that lockdown could have negative health consequences due to weight increase, behavioural changes and social isolation. Similarly, Mediouni et al. (2020) highlighted that a prolonged lockdown situation might increase the risk of mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. In this respect, and in the context of Spain, the research of González-Sanguino et al. (2020) found out that 20% of a sample of 3,480 adults presented symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress during the first month of lockdown. Even people who practiced physical activity regularly had mental health problems, especially people who practiced physical activity outdoors in groups (Rubio et al., 2021). Furthermore, Burstcher et al. (2020) concluded that the combination of home isolation and fear to contract COVID19 can lead to chronic stress, a risk factor to develop severe anxiety and depression problems. However, the practice of physical activity at home during lockdown could be beneficial to improve mental health according to studies of Reigal et al. (2021) and Symons et al. (2021).

Beyond mental health, physical inactivity because of COVID19 lockdown is problematic for overweigh population because it can increase existing metabolic problems (Martínez-Ferrán et al., 2020; Narici et al., 2020). According to them, people have tended to maintain their usual levels of food intake, whilst severely reducing calory burning through physical activity. Consequently, there is a bigger risk of metabolic problems and chronic diseases linked to obesity. In fact, Di Renzo et al. (2020) and Pellegrini et al. (2020) found that there was a high risk of increasing body weight after a month of lockdown, mainly due to the consumption of junk food and the decrease in physical activity.

On the other hand, amongst older population, Goethals et al. (2020) observed that lockdown (logically) was the main barrier to participate in group physical activity; the majority of older adults did no PA at home during lockdown. An associated problem of this lack of PA in older adults is the onset of joint-related pain, cardiovascular diseases and a negative impact on the immune system (Damiot, et al., 2020, see also Aspinall & Lang, 2018). Roschel et al. (2020) added that lack of PA increases the risk of sarcopenia, bone fragility and the appearance of pain and muscle fatigue, also analyzed by Martín-Moya et al. (2020).

Health benefits of physical activity during lockdown

Reference to the positive benefits of PA during the prolonged lockdown, several authors argued that PA could be a way to relief some of the most negative consequences of lockdown (Crisafulli & Pagliaro, 2020; Luzi & Radaelli, 2020). Matias et al. (2020) concluded that the practice of PA during lockdown was key to avoid emotional problems. Heffernan & Young (2020) argued that PA would reduce the risk of contracting pulmonary diseases during a prolonged time of indoor stay. On the other hand, Viana & de Lira (2020) argued that exercise and PA reduce the feeling of social isolation and Arora & Grey (2020) added that regular PA or exercise during lockdown improved sleeping patterns.

Nieman and Wentz (2019) suggested that exercise and PA help to enhance the immune system of the older population. Other authors argued that it can improve the performance of the circulatory system and help to combat viral infections (Amatriain-Fernández et al., 2020; Lim et al., 2020). In addition, the study of Gao et al. (2020) analysed exercise through virtual reality in older adults. They found that this solution to the lack of outside exercise still produced positive benefits, such as improving balance, preventing falls and improved cognitive capacity.

Problems and barriers to physical activity and exercise during lockdown

The practice of exercise during lockdown is not easy. Indeed, the COVID-19 lockdown caused a decrease in PA practice in Spain, both quantitively and qualitatively (García-Tascón et al., 2021; López-Bueno et al., 2020). This decrease in the practice of physical activity affected negatively people's well-being, especially in the case of those that were physically active before the COVID-19 pandemic (Martínez-de-Quel et al., 2021). Ranasinghe et al. (2020) argued that the use of new technologies was paramount to facilitate PA practice during lockdown, as they connected people willing to exercise at home with specialists in sport, training, and exercise.

Regarding the barriers to the practice of PA, before COVID19, Thind et al. (2016) and others explained that the main perceived barriers to PA practice were lack of time, lack of knowledge and lack of motivation. Researchers have found a variety of reasons to explain barriers to the practice of exercise or PA during lockdown. First, it is important to analyze the correlation between internet/technology consumption and (lack of) physical activity. Qin et al. (2020) undertook a study through a survey of 12,000 adults in China. They found that 60% of the participants reduced their PA during lockdown. At the same time, they also found that they increased the time dedicated to watch television, use tablets or computers by four hours per day on average. In this respect, Király et al. (2020) concluded that the use of technology, internet and streaming services increased worldwide during lockdown, with negative consequences to maintain a healthy and active lifestyle. In this regard, Cívico et al. (2021) and González (2019) have pointed out that an improper use of technology can lead to mental health and social relations problems, especially in teenagers. Moreover, Jiménez (2019) had previously found that some violent video games could increase the aggressive behavior of young players.

Other studies point towards different factors leading to inactivity during lockdown. Costandt et al. (2020) found out that those who did the lowest amount of exercise presented some of the following socio-demographic characteristics: people over 55, lower education levels, used to practice sport or exercise with friends, and those with the lowest use of online tools and services before lockdown.

Thus, researchers have found a rather eclectic mix of barriers to PA during lockdown. Some of these barriers are similar to the reasons expressed for not exercising before lockdown whereas others seem rather connected to the nature of life under lockdown. In this article we are interested, though, in analysing the impact on the return to PA and fitness routines once lockdown was over. Whether any of these problems encountered under COVID-19 might leave a 'legacy' on fitness and leisure centre users or not. This article is an empirical contribution to reflect on the consequences of COVID-19 in Spain.

METHOD

This study draws on a quantitative research design. Data collection was done through an online questionnaire sent to fitness centre users in Spain.

Sample

The sample for this study was obtained amongst the members of 84 fitness and leisure centres in different provinces of Spain. The 84 fitness centres belong to Fundación España Activa (a not-for-profit NGO organisation whose aim is to promote sport and physical activity in society). The research team, Alcalá de Henares University and Fundación España Activa designed this study together, which facilitated access of the research team to the managers and directors of the individual fitness centres in order to do the survey. We defined two inclusion criteria to recruit participants into the survey: They had to be 15 years old or more and be a member of the fitness centre when the COVID-19 lockdown started in Spain (15 March 2020).

We received 8,087 valid responses (37% response rate). Thus, the sample used in this study is a total of 8,087 members of fitness centres older than 15 years. The survey was built in a way that those participants stating they would return to their fitness centre after lockdown (88.9%) were then asked about the motivations to continue their PA routines. Those participants stating they would not practice sport or PA after lockdown (11.1%) were asked the questions about perceived barriers, the focus of this work. Therefore, the final sample of this research was 905 people.

Instrument

Data was collected through an online questionnaire sent by the fitness centres by email to all their members that met the inclusion criteria. The research team did not have access to the membership data base, nor to the personal data of the participants. Online questionnaires do come with limitations that need to be acknowledged, most importantly the self-selection of participants and non-probabilistic nature of sampling. We mitigated this limitation through the collection of a large number of valid responses. Moreover, there is an increasing agreement in the literature (see Manfreda et al. 2008) that the use online surveys in the social sciences offers similar levels of quality and rigor than traditional phone or face to face surveys. Indeed, recognised authors in the socio-scientific study of sport such as Cashmore and Cleland (2012, p. 345) argued that online questionnaires provide "more frankness and honesty" because the level of anonymity of the participants is higher.

Those taking the survey were adequately informed of the research objectives and their rights as participants before starting the questionnaire. They were also informed of their rights under GDPR and data protection legislation, clearly stating that the survey was collecting data under the public service legal basis and only for research purposes. Data has been collected, stored and treated at all time following the Spanish legislation (Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos 3/2018); the research followed the ethical guidelines of the reviewed World Medical Association's Helsinki Declaration (52th General Assembly, Edinburgh, Scotland, 12th October 2000), and the research ethics framework of the University of Alcalá de Henares (Madrid, Spain).

Participants had to give their informed consent in the survey's landing page before proceeding to the first question. Surveys were anonymous, and the only personal data collected were age and gender.

We built the survey with questions used in previously validated questionnaires. The survey was divided in two parts. The first part was composed by an abbreviated version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), previously used, and validated in several studies (e.g. Cleland et al., 2018; Lee, et al., 2011; Rubio et al., 2017). These questions addressed participants' PA practice. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) is indicated for adults, so in the online adaptation people under 18 years of age were not allowed to answer questions regarding frequency, duration and intensity of PA. But if they stated that they would not practice PA after the lockdown, they were asked to answer the questions regarding perceived barriers.

The second part of the questionnaire was composed by questions taken from Eurobarometer survey 472, wave 88.4 (European Union [EU], 2018). These questions referred to barriers to do sport and PA. From this questionnaire, 3 variables were used: you do not have the time, you lack motivation or are not interest and it is too expensive (price). Three other variables were included following consultation with professional experts in the management of sports facilities: lack of safety, lack of cleanliness and hygiene and practice PA al home or on my own.

Procedure

The validation of the questionnaire was done in three stages (Soriano, 2014). In Stage 1 we determined the objectives of our research. In Stage 2 the questionnaire was evaluated and assessed by a team of experts composed by six persons with an adequate level of knowledge on sport and fitness venue management. In Stage 3, we piloted the questionnaire with 10 directors of sport facilities in the region of Madrid (Spain). We gathered feedback from this piloting stage to fine tune the survey's final version before opening it to participants.

Data collection was done between 5th and 20th April 2020. The 'state of alarm' was still fully enforced in Spain. Consequently, the population was in complete lockdown. At the time of data collection participants had been in lockdown between 21 and 36 days, and they did not know when lockdown was going to be released.

Variables measuring physical activity

The IPAQ questionnaire measures the frequency, duration, and intensity of PA. The IPAQ questions included in our survey asked the number of days in which participants had done vigorous and moderate physical activity, and the average time (in minutes) per day for each type of activity. To facilitate statistical analysis we followed normal and accepted practice in the measurement of PA in adult population (see Clemente et al., 2020; Gerovasili et al., 2015; Mayo et al., 2019), and therefore time-related answers were categorised in five variables, assuming that answering "30 minutes or less" meant 15 minutes, "31 to 60 minutes" meant 45 minutes, "61 to 90 minutes" meant 75 minutes, "91 to 120 minutes" meant 105 minutes, and answering "more than 120 minutes" meant 120 minutes.

Only those participants that answered correctly the full questionnaire were eligible for statistical analysis in relation to the WHO's (2010) PA recommendations. To assess the degree of compliance with the WHO's recommendations, it was necessary to calculate the weekly time dedicated to vigorous and moderate physical activity. We classified as "adequately active" those doing at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity, 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity, or a combination of moderate and vigorous PA (Clemente et al., 2020; Gerovasili et al., 2015; Mayo et al., 2019).

Data analysis

Our statistical analysis strategy was divided in two stages. Firstly, we undertook descriptive statistics analysis to identify the barriers of fitness centres' users after lockdown. In the second stage we did a logistic regression analysis with each one of the barriers as dependent variables. The independent variables used were as follows: gender, age, degree of compliance with the WHO PA guidelines (as explained above), and the number of days of vigorous PA in the previous week (during lockdown). The choice of these independent variables was informed by previous research. These sociodemographic factors have been studied in published and highly reputed projects (e.g. Herazo-Beltrán, 2017; McGuire et al., 2016).

Regression results are presented as odds ratio (OR), with a confidence interval of 95% for each one of the barriers variables that was statistically significant (p <0.05). The type of answers referring to each one of the motives and barriers were presented as a dichotomous choice (yes or no), in a multi-answer format.

RESULTS

We start first presenting the overall results of the survey. Table 1 (below) helps us understand the characteristics of the sample. It presents the distribution of participants according the sociodemographic variables: age, gender, days of vigorous PA in previous week, and adherence to WHO PA guidelines.

The main objective of the study was to identify barriers to return to fitness centres after lockdown. The Table 2 presents perceived barriers to do PA after lockdown. These are: price (39.1%), lack of safety and protection against COVID-19 (37%), already doing PA at home/on their own (26.4%), and possible lack of hygiene in fitness centres (22%). Whereas there is a small difference, it is of interest that the economic barrier (price) is ahead of the health and safety barrier directly linked to COVID-19.

We move now to the perceived barriers and the relationship with the variables of age, gender, days of vigorous PA in the last week and WHO PA recommendations. These are divided in Tables 3 and 4 (below). As can be seen, the barriers that we found to be statistically significant are "lack of safety", "lack of cleanliness and hygiene", "doing PA at home/on my own", "lack of time", "lack of motivation or interest".

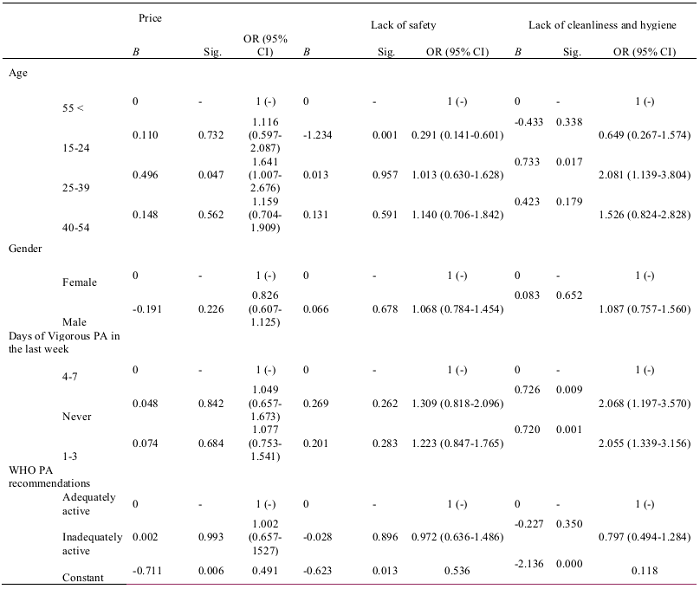

Table 3. Factors associated with the perception of barriers to physical activity: price, lack of safety and lack of cleanliness and hygiene.

Table 4. Factors associated with the perception of barriers to physical activity: PA at home or on my own, lack of time, lack of motivation or interest.

"Lack of safety" is less prevalent as a barrier in the youngest participants (15-24 years) [OR 0.29 (95% CI (0.14 - 0.60))], but it increases as we move along the age range. Interestingly, this is not replicated for "lack of cleanliness and hygiene". In this case we find the young adults (25-39 years) are the group that has the barrier more present. In relation to levels of physical activity, this barrier is more prevalent amongst those less active, especially those who did not any PA in the previous week [OR 2.07 (95% CI (1.197 - 3.570))].

Whereas "lack of safety" or "lack of cleanliness and hygiene" are barriers that could be addressed by fitness centres, the more personal situation of the users is, of course, more difficult to counter for the gyms and sport venues. We found three barriers that we could classify as personal. The first one is "doing PA at home/on my own". We find this barrier is less prevalent amongst participants classified as "inadequately active" because they do not comply with WHO PA guidelines [OR 0.41 (95% CI (0.24 - 0.69))], which is probably unsurprising (but also suggests the accuracy of the statistical analysis).

"Lack of time" is another barrier related to personal circumstances. In this case we find that it is most prevalent amongst the youngest participants (15-24 years) [OR 4.40 (95% CI (1.15 - 16.80))]. Finally, the barrier "lack of motivation or interest" is more prevalent in males than females [OR 1.99 (95% CI (1.09 - 3.67))].

DISCUSSION

The most common barrier to re-join the fitness centre after lockdown was price. This might be linked to the economic uncertainty that surrounded the COVID-19 pandemic, with a severe increase in the unemployment rate in Spain (Hermi & García, 2020). This is more relevant when we compare our findings with the results of the Eurobarometer (EU, 2008), where price was only a perceived barrier to PA for 7% of the EU population, being the fourth most important barrier. Thus, we can see how COVID-19 seems to have a significant effect in the perception of fitness centre users. Price has now risen to the forefront of their preoccupations. Given the severity of the economic crisis associated to COVID-19, fitness centres might have a reduction in demand to which they would have to adapt accordingly. The consequence of this for the practice of PA more widely is perhaps more difficult to predict. On the one hand, fitness centre users might not necessarily decide to stop their exercise routines, but they could opt for joining cheaper alternatives.

The second most important barrier revealed by our results is lack of safety, which is naturally linked to the nature of the public health crisis brought about by COVID-19. Moreover, it is also important to highlight that data collection took place during the hardest times of lockdown. For our purpose in this article, the reality is that fitness centre users are indeed worried about safety to a good extent, as it is their second most important perceived barrier to return. Thus, fitness centre managers should be aware of how prevalent this is to ensure return of their users. Similarly, Matos et al. (2021) observed that proximity with other users, touching common surfaces and the use of changing rooms could be barriers to practicing physical activity in indoor sports facilities.

The third perceived barrier refers to a situation that is, perhaps, far away from fitness centres' control, as it refers to users who are doing PA on their own at home using new technologies. In fact, the use of technological tools has increased greatly in the period of lockdown because it is the only hope to keep the economy on track (Xiang et al., 2021). Here the time in lockdown might have had an important effect, as we saw a rise in the number of free or low-cost apps, YouTube videos or Instagram/Tik Tok influencers dedicated to fitness and physical activity or their evaluation (Reigal et al., 2020). Thus, the new habit of exercising at home could be more relevant that it can appear at first sight. However, if that were to happen, it could well happen that those taking up fitness or PA would do it on their own, rather than in a fitness centre. Following from that, we can consider a wider reflection on the possibility that COVID-19 might have a relevant impact in fitness and PA habits. Although we are hypothesising here, our results point to preoccupations of price, safety, and also a new awareness about home exercise. In our view, this could lead to an increase of home/lone fitness routines, to the detriment of fitness centres or more social/organised environments. However, other studies suggest that the frequency of physical activity in the fitness center should also be taken into account as an intervening variable: People who go to the gym at least twice a week are less likely to stop attending a fitness center to practice PA (García-Fernández et al., 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2021).

The fourth barrier according to our results is lack of cleanliness or hygiene, which is logically linked to the doubts about the cleaning and safety protocols in fitness centres after lockdown. This barrier, we argue, could be paired with the lack of safety we have discussed in the paragraphs above as the second most important barrier. When taken together it seems clear that the health and safety protocols are going to be even more important than ever for fitness centres to ensure a return of their users in the new COVID-19 reality.

One important consequence of this relates to profitability. If we consider together users' preoccupation for price and safety/hygiene, this creates a difficult situation for the fitness centres. On the one hand, they might need to invest more on hygiene and safety; on the other hand, it might be difficult for them to recover that investment via membership increases. Thus, fitness centres will find themselves in the centre of an almost perfect storm created by COVID-19 where, if we go one step further, they might have users that prefer to stay at home, whereas those that decide to return might not do it unless the price is frozen/reduced and extra safety/hygiene measures are in place. It is therefore unsurprising that gym and leisure centre operators in Spain are requesting supporting measures from the local, regional and national governments (Murillo, 2020).

In fifth place appears the barrier lack of time, which has historically been the most important barrier to the practice of physical activity (Thind et al., 2016). According to age, in our study this barrier occurs more in people aged 15 to 24 years, coinciding with the study by Planas et al. (2020). Martín (2020) in her study on the impact of covid19 on the practice of AP in adults, argued that lack of time was a more relevant variable in women than men, because the health crisis forced women to dedicate more time to childcare due to school closures; it was also relevant because women are the majority of the staff working in sanitary and essential services.

However, in the teenager age bracket lack of time was a more important barrier for males than for females (Domínguez-Alonso et al., 2018). In this regard, Sevil et al. (2017) found that lack of time was the main barrier perceived in adults studying at university, without significant differences according to gender.

For our discussion here, several existing studies on the perceived barriers to PA practice share similar findings. Usually, these barriers are: lack of time; health problems or illnesses; laziness or prefer to do other things; lack of motivation or interest; excessive fitness effort required; lack of family support; fear to do exercise; the price; distance of sports facilities; lack of skills; embarrassment of practice PA with work colleagues, among other (Camargo et al., 2021; Herazo-Beltrán et al., 2017; McGuire et al., 2016; Mondaca et al., 2020; Karunanayake et al., 2020; Portela-Pino et al., 2019; Rech et al., 2018; Samperio et al., 2016; Shin et al. 2018; Silva et al., 2020; Spiteri et al., 2019; Thind et al., 2016). In most of these studies, lack of time is the main perceived barrier to PA practice. Other reasons in second place are barriers related to health problems, the excessive levels fitness effort required to do PA, or family reasons. In these studies, however, price did not normally appear as one of the main barriers to PA practice. We can see a real change in the perceptions for the new reality after COVID-19. Price has jumped to the top of the list in our results. Of course, with the data at our disposal we cannot claim this is purely and solely a change because of COVID-19, but it is certainly a plausible explanation. And specially the case of price is such a significant change (from bottom to top of the barriers' list), that we would argue our results point towards an important change in the environment with likely consequences for the sector.

APLICACIONES PRÁCTICAS

This study is first and foremost an empirical contribution to reflect on the consequences of COVID-19 for sport. This information is relevant to fitness centre managers, leisure centre operators, but also to public authorities that might offer PA services to the population (note that in Spain provision of sport facilities is a competence of local councils, and many of them operate public leisure centres). Our results provide valuable and timely information to adapt the services in order to overcome the most important perceived barriers to return to PA practice after lockdown.

Additionally, our study also provides information of interest for public authorities to plan upcoming policies promoting healthy lifestyles in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The promotion of a healthy lifestyle that could prevent diseases linked to sedentarism is perhaps now more important than ever given the stress which the public health service is under in Spain, like in most European countries. Allegedly, any savings in health costs that could be done through the promotion of fitness or PA could be an extra resource dedicated to fight COVID-19, the most important health emergency in Spain for a century.

Limitations and future research

We already touched on the methodological limitations of the study in the methods section due to the non-probabilistic sample, and these are acknowledged here again. Furthermore, we also need to acknowledge that one of the limitations of the study lies in the fact that our sample was restricted to fitness centre users. We cannot claim our results are generalisable to the wider population, nor to non-active people. On the other hand, we could argue that this limitation can be turned an advantage for fitness centre operators, as the results provide very focused information to retain their users in a very difficult environment.

Building on our findings, a first avenue for further research would be to undertake the survey once more with the same sample within a year of the end of lockdown to assess any changes. A different (yet complementary) line of enquiry would be to do a similar study with non-active population to compare whether the results are different to the views of the active population. Furthermore, in both cases it would be of interest to study different predictive variables, such as level of study, income, marital status, or expenditure in sport activities.