INTRODUTION

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in the general population and in particular among children and youth are a global health concern (Ng et al., 2014; WHO, 2016)., although their prevalence in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) ranges from 3.2% in Timor-Leste to 83.5% in Tonga among adult males (>20 years) and from 4.7% in the Democratic Republic of Korea to 88.3% in Tonga among adult women (Ng et al., 2014). It has been suggested that obesity is increasing more rapidly in LMICs due in large part to major changes in diet (Swinburn et al., 2011).

Cabo Verde, a country comprised of several islands approximately 620 km off the west coast of Africa, is in the midst of a nutritional transition as are other LMICs (Caballero, 2005). The prevalence of overweight and obesity in Cabo Verde is higher in adults (respectively, 44% and 15% in women; 31% and 7% in men) compared to the population <20 years (respectively, 18.3% and 5.2% in girls; 11.5% and 3.3% in boys) (Ng et al., 2014). However, a recent survey indicated a lower prevalence of overweight (7.0%) and obesity (1.7%) among Cabo Verde adolescents of both sexes 12 to 17 years (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2018).

Although physical activity (PA) is often a focus of discussions of weight status, it is also a determinant of healthy weight. PA is negatively related with body fatness and positively associated with physical fitness (PF) (Ortega et al., 2013; Rafaello Pinheiro et al., 2021) and motor competence (MC) (Lopes et al., 2012) among youth. The latter is the currently used term addressing a person's proficiency in motor skills (Utesch & Bardid, 2019), although the label movement proficiency is also used (Malina et al., 2016). Evidence is also reasonably consistent in highlighting potential interactions among PA, PF and MC as factors affecting weight status (Stodden et al., 2008; Teixeira et al., 2022), although the potential role of genetic factors also merit consideration (Bouchard et al., 1997; Malina, 1986a). In addition, the proposed models are largely set in the western cultural context, while data systematically addressing relationships among nutritional status per se, weight status, PA, PF and MC in non-western cultures are limited (Malina, 1984, 1986b; Manyanga et al., 2020; Manyanga et al., 2019), and the need for a biocultural approach recognizing potential interactions between biological and culture-specific factors has also been indicated (Malina et al., 2016).

A good deal of the current literature on relationships between PA, PF and MC, on one hand, and weight status on the other hand, is often focused on the overweight and obese who tend to have subpar levels of movement skills (Lopes et al., 2014; Lopes et al., 2020) and fitness (Bovet et al., 2007; Huang & Malina, 2007, 2010; Lopes et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2016).On the other hand, children and youth living under poor and/or marginal nutritional conditions tend to show stunted growth and deficiencies in motor development and skills (Malina, 1984, 1986b). Among indigenous children in southern Mexico, for example, normal weight and growth stunted children 6-13 years did not differ in fitness, whereas overweight/obese youth were absolutely stronger but had lower strength per unit mass and endurance (Betancourt Ocampo et al., 2022; Malina et al., 2011). In samples of Mozambique boys and girls 6-18 years and statistically controlling for age, pubertal status and socioeconomic status, overweight boys and girls performed poorly compared to thin, normal weight and growth stunted peers on several fitness tests. In contrast, compared to normal weight boys and girls, growth stunted, thin and stunted and thin boys and girls performed poorer in absolute strength tasks, better in endurance tasks and equally as well as normal youth in flexibility and agility (Prista et al., 2003). Although chronological age and pubertal status were statistically controlled, the broad age span limits comparisons with other studies. More recently, a study of 14 year old South African youth, a gradient of underweight > normal weight > overweight/obese was noted among girls for the standing long jump, sit-ups and bent arm hang, while performances of boys on the fitness tests were more variable: jump - normal weight > underweight > overweight/obese, bent arm hand - underweight > normal > overweight/obese, sit-up - underweight > normal weight > overweight/obese (Monyeki et al., 2012).

A recent systematic review (Muthuri et al., 2014) enumerated 71 reports which considered PA, PF and sedentary behaviour of sub-Saharan school-aged youth. Urban, higher socioeconomic status girls generally showed lower levels of aerobic fitness and PA and greater sedentary behaviour. Urbanization was also associated with a trend towards reduced PA, increased sedentary behaviour, and decreased aerobic fitness over time. Unfortunately, the systematic review did not consider variation in nutritional and weight status among samples.

In the context of the preceding, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate variation in PA, PF and MC associated with weight status of adolescent boys and girls resident in Cabo Verde.

MATERIAL AND METOTHS

Participants

Students in secondary public schools located on Santiago Island, Cabo Verde, were invited to participate in the study. Cabo Verde is comprised of ten islands and eight islets that are located approximately 620 km off the west coast of Africa, and had a population of about 520,000 in 2015 (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2015). The population is largely of mixed African and European ancestry; it is predominantly of European ancestry in the male lineage (43%) and of West African ancestry in the female lineage (57%) (Beleza et al., 2012).

About 65% of the Cabo Verde population live in urban centres. More than one-half of the population (56%) lives on Santiago Island, which had a population of 297,904 in 2014 (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2015). In addition, 23 868 adolescents (12 to 15 years) attended secondary school, and about one-half (11,141) were resident in Praia, the capital of Santiago Island (Ministério da Educação, 2016).

Six of the 29 secondary public schools located in Santiago Island were the focus of this study, three in the Praia municipality and three outside the municipality. The study was authorized by the Ministry of Education of Cabo Verde. All procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Written informed consent was initially obtained from the participating schools and after that from the parents of individual boys (n=145) and girls (n=198) within the age range of 12.0 through 14.9 years (overall, 13.5±0.8 years). Each of the individual youth also provided verbal assent prior to data collection. Any physical or mental deficiency that could condition the performance of the different tests was an exclusion criterion.

Instruments

Anthropometry. Stature and body mass were measured using a stadiometer (Seca, model 203) and a scale (Seca, model 750) following standard procedures (Marfell-Jones et al., 2012). Values were recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm and 100 g, respectively. Technical errors of measurement were 0.20 cm and 0.26 kg for height and weight, respectively. The body mass index (BMI, weight /height2 ) was calculated. Weight status was classified relative to the IOTF cut-off values for the BMI (Cole et al., 2000; Cole et al., 2007). Participants were grouped into three weight status categories: thin, normal, and overweight plus obese (OWT/OB).

Physical Activity. PA was estimated over seven consecutive days using New Lifestyles pedometers (NL-800). Students were instructed to wear the pedometer during waking hours and not to remove the device, except for bathing, swimming, or sleeping. It was attached to an elastic belt strapped firmly over the waist, above the right hip and aligned over the knee. The average of the daily number of steps was used as the indicator of PA. Records of step counts over at least 6 days and for at least 10 hours per day were accepted as valid.

Physical Fitness. In addition to grip strength of the dominant hand, four items from Fitnessgram battery were administered (Welk & Meredith, 2008):

Upper-body strength/endurance (90º push-up). The participant was required to be lie face down on the floor with the hands placed under the shoulders. The student was instructed to push-up to full arm extension so that body weight was resting on the hands and toes. Then, keeping the body straight, the student lowered the body to the ground until the arms were at a 90° angle. The push-ups were continued until the student could no longer maintain the target rhythm or reached the target number of 75 push-ups. The number of correctly completed push-ups performed in time with the rhythm was recorded.

Abdominal muscular strength and endurance (curl-up). Lying on the back, knees flexed at approximately 140o and feet flat on the floor and the arms straight and parallel to the trunk with the fingertips resting on the near edge of the measuring strip, the student was instructed to curl-up slowly, sliding their fingers across the measuring strip until the fingertips reach the other side, then to curl back down until their head touched the mat. The test was continued until exhaustion (e.g., the subject could not maintain the rhythm), or until the student completed 75 curl-ups. The total number of curl-ups was recorded.

Hamstring/lower back flexibility (back-saver sit-and-reach). With shoes removed and the student sitting on the floor with one leg extended straight out so that it was flat against the measuring box, the other leg bent at the knee with the foot flat on the floor and hands placed on top of each other and palms facing down, the subject reached slowly forward as far as possible. The participant repeated the test three times and the best score the nearest centimeter was retained. The test was repeated for the opposite leg. The average of the best score for each leg was retained for analysis.

Cardiorespiratory fitness (one mile run/walk). The student was instructed to complete one mile in the fastest possible time. The running surface on the school playground was flat and was marked to provide 200 m perimeter. Although students were instructed to cover the distance as quickly as possible, they could run, walk, or intersperse walking and running. The time to complete one mile was recorded in minutes and seconds.

Grip strength of the dominant hand was measured with a hydraulic handgrip dynamometer (Baseline 12-0241 Lite, New York, U.S.). Three trials were given, and the highest value was retained for analysis. Prior to the test, the dynamometer was adjusted for hand size. The highest grip strength (kg) was expressed relative to body mass as grip strength (kg)/body mass (kg)].

Motor Competence. Although a variety of tests are available to assess MC, the Körperkoordination Test für Kinder (KTK) or body coordination test (Kiphard & Schilling, 2007) was used in the present study. The KTK is a product-oriented assessment appropriate for children and youth 5 through 14 years of age. The KTK battery includes four items which assess gross body control, coordination, and dynamic balance:

Walking backwards on balance beams (length 3 m, height 5 cm) of different widths (6.0, 4.5 and 3.0 cm). The maximum score was 72 steps, based on 3 trials per beam and a maximum of 8 successful steps for each trial.

Hopping for height, one foot at a time, over an increasing pile of soft blocks (height 5 cm, width 60 cm; depth 20 cm). The maximum test score was 39 points (ground level + 12 blocks) for each leg, with a maximum of 78 points for both legs.

Jumping sideways from side to side over a thin wooden lath (60 cm × 4 cm × 2cm) on a jumping base (100 cm × 60cm). Two trials of 15 seconds were performed and the total number of successful jumps in the two trials was retained as the score.

Moving sideways while shifting platforms. The student had two identical wooden plates (25 cm × 25 cm, height 5.7 cm). Standing on one plate, the student had to move sideways to the other plate, retrieve the first plate and place it to his/her side, and then move to the plate, etc. Two 20 second trials were given, and the number of successful transfers over the two trials was the score.

The performance score for each test item was converted into a "motor quotient" using normative data tables adjusted for age and sex (Schilling, 2014). The sum of the motor quotients for each item provided a global motor quotient (MQ) which was used for analysis.

Procedures

The data were collected from January to March 2017, during school hours in physical education (PE) classes. The first author supervised all assessments and made all anthropometric dimensions. He was assisted by the PE teacher of the class and a team of ten students of sport science from Cabo Verde University, trained in the use of the instruments and of the test protocols. The tests were administered over two days. Anthropometry and MC assessment were done on the first day, while tests of PF were done on the second day. The one-mile run/walk was the last test performed. Between tests, there was a rest interval of at least 5 minutes, and the subsequent test was only performed after the participant indicated that he/she was not tired. To estimate reliability, all anthropometry, MC and PF test were performed a second time, a week later, in 30 participants (15 boys and 15 girls).

Quality Control. Reliability of measurements was estimated with intraclass correlations. Estimated reliability was high for height and weight, 0.97 and 0.99, respectively; and moderately high to high for the PF items, 0.71 to 0.98 and for the MC test items, 0.74 to 0.90.

Data análisis

Sex-specific descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were calculated for all variables. The normal distribution of the data was verified by the Kolmogorov - Smirnov test. Chi square was used to compare the prevalence of thinness, normal and OWT/OB between boys and girls. Univariate analysis of covariance, controlling for age, age squared, and height (only in boys) was used to compare PF, MC and PA of thin, normal and OWT/OB among boys and girls, respectively. The AnthroPlus software (WHO, 2018) was used to calculate the Z score of height- and BMI-for-age relative to the WHO Child Growth reference (WHO, 2006). All other calculations were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2016, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

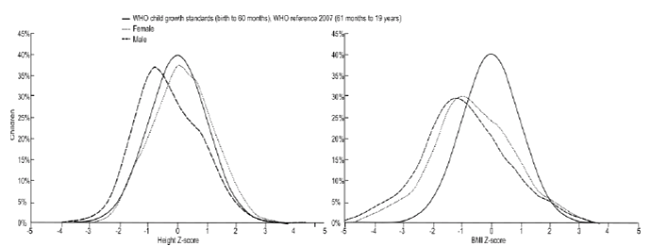

Figure 1 displays height-for-age and BMI Z-scores for boys and girls relative to the WHO reference (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006). Weight-for-age is not shown because reference data are not available beyond 10 years of age, as most children are in their pubertal growth spurt and the differential timing of growth spurts in height and weight may influence weight-for-height relationships (Butte et al., 2007; WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006). Cabo Verde adolescents boys are slightly shorter than the WHO reference, 50% have a height-for-age below -0.5 Z score. On the other hand, the height-for-age Z-score for girls are similar to WHO reference; 50% have a height-for-age below 0.2 Z score. Most of boys and girls have a BMI-for-age below the WHO reference, 50% of the boys and girls have a BMI for age below -0.97 and -0.72 Z score, respectively.

WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006

Figure 1. Height and BMI Z-scores for age according WHO reference.

Overall, the majority of boys and girls is classified as normal weight, 80 (56%) and 117 (59%), respectively, while about one-third of boys and girls are classified as thin, 51 (36%) and 62 (31%), respectively. In contrast, small percentages of boys and girls are classified as either OWT or OB, 12 (8%) and 19 (10%), respectively. The prevalence in weight status categories is similar in boys and girls (χ2 = 0.63, p = 0.74).

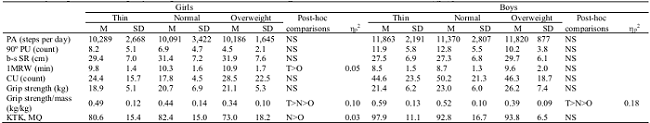

Descriptive statistics for PA (average of daily steps) and for specific PF and MC items are summarized by weight status and sex in Table 2. Results of the ANCOVAs indicated significant differences among weight status categories for only three items in girls and one item in boys. The one mile run/walk (F(gl: 4, 2) = 5.01; p = 0.008), grip strength per unit body mass (F(gl: 4, 2) = 15.44; p<0.001) and MC (F(gl: 4, 2) = 3.40; p=0.035), differed significantly among weight status groups of girls. Thin girls performed better than OWT/OB girls (p=0.008) in the one-mile run/walk, but the effect size was low; only 5% of the variance was attributable to weight status. For grip strength per unit body mass, OWT/OB girls scored lower than normal weight (p = 0.007) and thin (P<0.001) girls, while normal weight girls scored lower than thin (p=0.026) girls. Overall, 10% of the variance in grip strength per unit body mass was attributable to weight status. For MC, OWT/OB girls scored significantly lower than normal weight girls (p=0.003), but the effect size was low; only 3% of the variance was attributable to weight status.

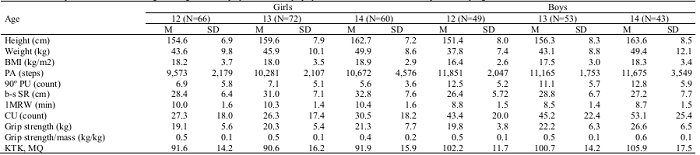

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for height, weight, BMI, physical activity, physical fitness and motor competence by age and sex.

Notes:M = mean; SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index; PA = physical activity; 90º PU = 90º push-ups; b-s SR = back-saver seat-and-reach; 1MRW = One mile run/walk; KTK, MQ = KTK motor quotient.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) for physical activity, the physical fitness tests and the motor quotient (MQ) of the KTK test by weight status among boys and girls, and results of ANCOVA [pairwise differences and effect sizes (ηp2)].

Notes. PA = Physical activity; 90º PU = 90º push-ups; b-s SR = back-saver seat-and-reach; 1MRW = One mile run/walk; KTK, MQ = KTK motor quotient; NS = no significant differences between weight status categories; O = OWT/OB; N = normal weight; T = underweight.

Among boys, only grip strength per unit body mass differed significantly among weight status groups (F(gl: 5, 2) =15.39; p<0.001). OWT/OB boys had less strength per unit mass than normal weight (p = 0.002) and thin (P<0.001) boys, and normal weight boys had less strength per unit mass than thin (p=0.002) boys. The effect size was relatively low; 18% of the variance was due to weight status.

DISCUSSION

Associations between level of PA and indicators of PF and MC and weight status were considered in Cabo Verde youth 12-15 years. The estimated prevalence of OWT and OB was low (<10%), while the estimated prevalence of thinness (underweight) was considerably higher (33%). The results were consistent with a recent survey of Cabo Verde youth 12-17 years which showed a combined prevalence of OWT/OB of about 9% (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2018). These estimates for OWT/OB were also consistent with results of a meta-analysis of 45 studies of primary school children in 15 African countries which indicated a prevalence of 9.5% for OWT and 4.0% for OB based on IOTF criteria (Adom et al., 2019). In the latter review, estimates were similar among boys and girls, but generally higher in urban settings and private schools. Nevertheless, evidence also suggested that the BMIs of Cabo Verde boys and girls (5 to 19 years) increased between 1975 and 2016, resulting in an increased prevalence of OWT/OB and decreased prevalence of thinness (Abarca-Gómez et al., 2017; NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, 2020).

PA levels were relatively high in the present study and did not differ among weight status groups. The median number of daily steps in Cabo Verde boys and girls (10,164), independent of weight status, was higher than the number of daily steps indicated as the minimum recommended amount of moderate-to-vigorous PA (Tudor-Locke et al., 2011). According to the suggested criterion (Tudor-Locke et al., 2004), 64% of youth in the present study were classified as active; by weight status groups, the estimated percentages were 70% of thin youth, 60% of normal weight youth, and 80% of OWT/OB youth.

Corresponding studies of PA among sub-Sahara African youth are limited in general and studies using objective indicators of PA are rare. In a cross-sectional survey conducted in an urban area of Nigeria, PA was assessed by self-report (Oyeyemi et al., 2016); only 47% of secondary school adolescents 12-18 years engaged in 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA per day. Based on accelerometery, rural boys and girls 12-16 years in Mozambique, accumulated 144.1 (boys) and 139.2 (girls) minutes per day in moderate PA (Prista et al., 2012). Although the instruments are not directly comparable, it is suggested that 10,000 to 11,700 steps per day in adolescent boys and girls is associated with 60 minutes of MVPA (Tudor-Locke et al., 2011). Cabo Verde youth in the present sample have, on average, higher estimates of moderate PA compared with Portuguese (Lopes et al., 2007; Prista et al., 2009) and North American (Katzmarzyk et al., 2016) adolescents. In contrast to the preceding and the present study, a pooled analysis of cross-sectional surveys worldwide, 86% of adolescents in 16 sub-Saharan countries (Cabo Verde was not included) had insufficient PA relative to the recommendations of the World Health Organization, i.e., at least 60 min of daily MVPA (Guthold et al., 2020).

Comparisons of specific PF items among youth of different weight status classifications suggested significant differences in cardiorespiratory fitness and in grip strength per unit body mass (Table 2). The literature suggests a curvilinear relationship between several PF tests and with BMI, i.e., children and youth of normal weight tend to have, on average, better performances on fitness tests compared to those who are thin (underweight) and OWT/OB (Kwieciński et al., 2018; Lopes, Malina, Gomez-Campos, et al., 2018; Lopes, Malina, Maia, et al., 2018). On the other hand, an inverse relationship, i.e., a decrease in PF from normal weight to the thin (underweight) OWT/OB tails of the BMI distribution (Mak et al., 2010) and an inverted J-shape relationship between the BMI and selected PF items (García-Hermoso et al., 2019) have also been reported. These types of relationships were not apparent in the sample of Cabo Verde adolescents, which likely reflected the limited distribution of the BMIs in the samples of boys and girls, i.e., few participants had BMIs that would classify them as moderately and severely thin and as obese (Cole et al., 2007; WHO, 2010). MC was independent of weight status in the present study, and boys performed better than girls. As suggested for PF, the literature also indicates a curvilinear relationship between MC and the BMI (Lopes, Malina, Maia, et al., 2018).

The present study is not without limitations. First, the sample was not randomly selected and does not represent the entire adolescent population in Cabo Verde. Second, an indicator of pubertal status was not available. This is of relevance as the evidence suggests better performances of early maturing boys in measures of strength, power and speed, which likely reflect their larger body size and muscle mass compared to average and late maturing peers, while early maturing girls often perform poorer on several tasks, perhaps due to a heavier body mass relative to height and perhaps a higher fat mass (Malina et al., 2004; Malina et al., 2015). In addition, an indicator of body composition was not available in the present study. Third, as with any cross-sectional study, it is not possible to infer causality between weight status and PF, MC and PA, although some research suggests that the relationship may be reciprocal (Robinson et al., 2015). The later needs clarification.

CONCLUSION

Cabo Verde adolescents were largely of normal weight, but proportionally more were thin (underweight) than OWT/OB. Independent of weight status, Cabo Verde youth of both sexes showed, on average, high levels of PA. Differences among youth by weight status were not apparent except for the one-mile run in girls and grip strength per unit body mass in both sexes. MC differed by weight status among girls but not among boys.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION

Although the PA, PF and MC of this sample of Cabo Verde adolescents are relatively good, policy makers in Cabo Verde should, nevertheless, consider the development of strategies and programs aimed at the maintenance of youth PA, PF and MC levels in the context of a nutritional transition and lifestyle changes associated with potential westernization