Introduction

Hope is one of the personal strengths that has been associated with well-being and many other positive outcomes (Alarcon, Bowling, & Khazon, 2013; Ciarrochi, Parker, Kashdan, Heaven, & Barkus, 2015). However, a cultural reading of the theory suggests that hope has been defined using a form of agency that is more important in individualistic cultures, and that other forms of shared agency are associated with hope in more collectivistic cultures (Bernardo, 2010). In the current study, we explore this notion of different forms of hope and how they relate to self-esteem and life satisfaction in three Asian cultures. In doing so, we hope to contribute to discussions of how there are dimensions of personal strengths that might vary across cultures and how cultural dimensions should be considered in better understanding how personal strengths relate to positive outcomes in diverse cultural contexts.

Hope, locus-of-hope, and well-being

Hope theory provides the most popular definition of hope in the psychology literature; the theory defines hope as positive thoughts related to an individual's commitment and approaches to attaining important life goals (Snyder, 2002). In its emphasis on the individual's determination and strategies towards goal attainment, hope is more than optimism or having a positive outlook. Using this definition of hope and its popular measure of dispositional hope (Snyder et al., 1991), extensive research studies have documented how hope is positively associated with wellbeing (Feldman, Rand, & Kahle-Wrobleski, 2009; Marques, Lopez, & Pais-Ribeiro, 2011) and in moderating the effects of various threats to well-being (Ashby, Dickinson, Gnilka, & Noble, 2011; Visser, Loess, Jeglic, & Hirsch, 2013). Hope is also associated with numerous positive outcomes in different life domains including learning in schools (Feldman & Kubota, 2015; Gilman, Dooley, & Florell, 2006; Marques et al., 2011), career exploration (Hirschi, Abesselo, & Froidevaux, 2015), healthy behaviors (Berg, Rapoff, Snyder, & Belmont, 2007), family cohesion (Merkaš & Brajša-Žganec, 2011), and many others. On the other hand, lower levels of hope are associated with negative mental health (Jovanovic, 2013), suicidal ideation (Chang, 2017), and more severe psychological symptoms brought about by traumatic experiences (Chang et al., 2017).

Viewing hope through a cultural lens

Applying a cultural lens, Bernardo (2010) suggested that hope theory implicitly assumes that positive goal directed thoughts refer only to the individual person's capacities and abilities; he further asserted that goal attainment could also involve actions of external agents, which relates to a view of shared agency common in more collectivist and/or interdependent cultures. The cultural reading was premised on some important distinctions between collectivist and individualist societies. Hofstede (1980) originally proposed contrasting societies on the basis of individualism and other dimensions, and he conceptualized individualist societies as one where ties among individuals are loose and operationalized this with reference to values and preferences of workers (e.g., valuing personal time and choice, etc.). He also defined collectivist societies as the opposite, wherein people are strongly integrated into groups. Although psychologists continue to debate the validity of using individualismcollectivism dimensions to classify cultures and societies (see e.g., Takano & Osaka, 2018) particular as societies undergo cultural change (Hamamura, 2018), most psychologists have come to conceptualize individualism and collectivism not simply as opposites but as worldviews that differ in the values, goals, and issues that they make salient to individuals (Kagitcibasi, 1997; Triandis, 1995). More importantly, psychologists have identified core domains of concepts that relate to individualism and collectivism beyond workplace behaviors. For example, across many studies reviewed by Oyserman, Coon, and Kemmelmeier (2001), individualism was related to seven major domains (independence, personal goals, competition, uniqueness, privacy, self-knowledge, and direct communication), while collectivism was related to eight domains (relatedness, belonging, duty, group harmony, advice seeking, adjusting to contexts, hierarchical relations, and group work). These domains are also reflected in various individual level measures of individualism and collectivism (e.g., Singelis, Triandis, Bhawuk, & Gelfand, 1995; Shulruf, Hattie, & Dixon, 2007).

Some of the core concepts salient in individualist societies underlie the premises of Snyder's (2002) hope theory. For example, individualism is conceptualized as a worldview that is organized around the individual's personal goals, qualities, and control (Kagitcibasi, 1997; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1995). Bernardo (2010) argued that this emphasis on personal goals and personal control seems to be assumed in the Snyder's (2002) hope theory, which implies that the attainment of goals depends on the individual's personal determination and strategies. Bernardo invoked Marcus and Kitayama's (2003) distinction between disjoint and conjoint models of agency. A disjoint model of agency implies that actions are defined independent of other people, are expressions of the individual's own purposes and preferences, and downplay other people's roles. In comparison, a conjoint model of agency implies that an individual's actions may be defined collectively, and relate to roles, responsibilities, and expectations of or related to significant others. Goal intentions and tendencies are defined interpersonally, goal pursuit and attainment could also be an interdependent process. Hope theory seems to assume a disjoint model agency, which is typical in American middleclass communities and other societies that emphasize individualism (Marcus & Kitayama, 2003), while being silent about goal pursuit that involves the conjoint forms of agency that is said to be more typical in Asian and other collectivist societies. Therefore, the cultural reading of hope theory suggests that the theory may be incomplete, as it does not recognize that hopeful thoughts might involve the role of external agents and pathways involving these agents.

To extend hope theory, Bernardo (2010) proposed internal and external locus-of-hope dimensions of hope-related cognitions. Thus, in addition to the dispositional hope defined in hope theory (Snyder, 2002), three external locus-of-hope dimensions were proposed that refer to hopeful cognitions related to the attainment of goals through conjoint agency with family, peers, and spiritual forces (i.e., external-family, external-peer, and externalspiritual loci-of-hope); the original conception of hope is referred to as internal locus-of-hope. The proposals were aligned with the core dimensions of relatedness, advise seeking, and group action associated with collectivism (Oyserman et al., 2002; Triandis, 1995). Moreover, wellbeing in collectivist societies tend to refer to processes involving the fulfillment of social roles and obligations and avoiding failures that might affect the groups collective status (Marcus & Kitayama, 1991), again emphasizing processes that extend beyond the individual person.

Consistent with these assumptions, early work suggests that the external locus-of-hope dimensions are associated with individual level collectivism and interdependent self-construals, whereas internal locus-of-hope is associated with individualism and independent selfconstruals (Bernardo, 2010; Du & King, 2013). Studies with various Asian samples have found that the proposed external locus-of-hope dimensions are related to positive psychological outcomes (Bernardo & Estrellado, 2014, 2017b; Bernardo, Salanga, Khan, & Yeung, 2016; Bernardo, Wang, Pesigan, & Yeung, 2017), including in young adolescents (Bernardo, 2015). Recent studies have further shown how external locus-of-hope dimensions buffer the effects of stress on well-being (Bernardo & Resurreccion, 2018; Datu & Mateo, 2017). But some studies also point to how particular external locus-of-hope dimensions related to negative psychological outcomes like maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., Bernardo & Estrellado, 2017a), and that these vary across different Asian cultural groups (Bernardo, Yeung, Resurreccion, Resurreccion, & Khan, 2018). Such diverse results across cultural samples suggest that the particular dimensions of this personal strength might have very cultural-specific meanings and impacts on well-being. As such, it is important to explore hope locus-of-hope dimensions function as personal strengths in diverse cultural groups.

Pathways from locus-of-hope, selfesteem, to life-satisfaction

One of the proposed mechanisms relating the personal strength of hope to well-being relates to the mediating role of self-esteem. As regards the internal and external locusof-hope dimensions, Du et al. (2015) proposed that the social cognitive processes associated with the locus-of-hope dimensions draw attentional focus to aspects of ones' self and self-evaluations. In particular, hope theory and the locus-of-hope extension assume that the personal strength of hope is essentially a cognitive mechanism, which requires the individual to assess the hope agent's capacity and strategies related to attainment of one's goals. Thus, in the case of internal locus-of-hope, the focus is drawn to the individual's personal abilities, strengths, and efficacy towards goal attainment, which all relate to one's self-esteem (Snyder, 2002). The positive evaluations of oneself are then associated with more positive cognitive appraisals of one's subjective well-being or satisfaction with life (E. D. Diener & M. Diener, 2009; Douglas & Duffy, 2014). But in collectivist societies, the person is an integrated part of social units (family, peers), and as such, the assessment of the hope agent, so the focus is also drawn to the individual's status relative to these important social groups, which is reflected in one's relational self-esteem (Du, King, & Chi, 2012), which is also an important contributor to well-being (Du, King & Chi, 2017; Du, Li, Chi, J. Zhao, & G. Zhao, 2018). Thus, as demonstrated in Du et al. (2015), internal locus-of-hope's relationship with life satisfaction was actually mediate by both personal and relational self-esteem.

But the external locus-of-hope dimensions are assumed to relate to self-esteem in more complex ways. It is possible, for example, that emphasizing the role of family and peers in attaining important life goals might indicate and therefore call attention to one's personal inadequacies or inabilities related to pursing these goals; in this sense, hopeful thoughts that highlight the role of others, might undermine one's personal self-esteem. But the same external locus-of-hope related thoughts could also call attention to one's self-worth related to group-level roles in important relationships, or to one's relational self-esteem (Du et al., 2012). In other words, relying on the agency of family and peers in pursuing life's goals indicates that one has good relationship status with these significant groups. These contrasting processes were reflected in Du et al.’s results (2015); external-peer locus-of-hope negatively predicted personal self-esteem, and indirectly life satisfaction; but external-family locus-of-hope positively predicted relational self-esteem, and indirectly, life satisfaction.

Du et al. (2015) tested the mediating roles of personal and relational self-esteem on the association between lociof-hope and life satisfaction with a Chinese sample, which is an important contribution in personal strengths research by way of testing relevant processes and outcomes in non- Western samples. But even among Asian cultural groups there are likely to be variations in how the locus-of-hope dimensions relate to subjective well-being (Bernardo et al., 2018). In line with the need to further explore the cultural dimensions of how personal strengths contribute to well-being, there is a need to further explore whether the models validated in one cultural group also apply to other cultural groups.

The current study

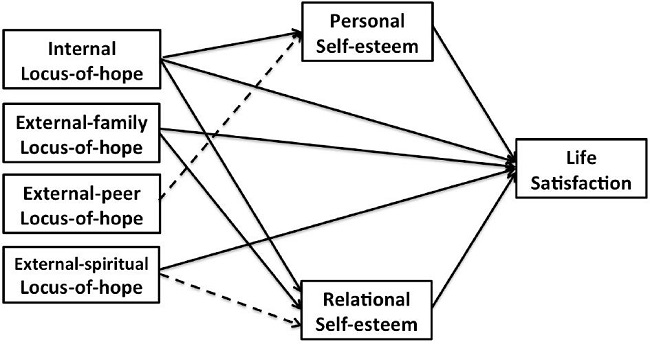

In this study, the model validated in Du et al. (2015) with a Chinese sample was tested with a Malaysian, a Filipino, and another Chinese sample. The model is depicted in Figure 1 which shows that there are three indirect effects relating specific loci-of-hope and life satisfaction. We discuss the hypotheses related to these three indirect effects below.

Figure 1. Path model of hypothesized mediated relationships between loci-of-hope and life satisfaction. Adapted from “Locus-of-hope and life satisfaction: The mediating roles of personal self-esteem and relational self-esteem” by Du et al., 2015, Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 228-233.

The first indirect effects involve internal locus-of-hope and life satisfaction, mediated by personal self-esteem and by relational self-esteem. As discussed earlier, the thought processes related to the personal strength of hope direct one's attention to the self as the agent of goal pursuit, and a positive evaluation of the self's capacity to meet goals is assumed to be associated with life satisfaction. Among individuals in collectivist societies, the appraisal of the self involves not just personal self-esteem but also relational self-esteem, which reflects an assessment of one's status with significant others. Thus, the first hypothesis in the study is:

(a) Personal self-esteem and relational self-esteem both mediate the relationship between internal locus-ofhope and life satisfaction.

The second indirect effect refers to the positive relationship between external-family locus-of-hope and life satisfaction, mediated by relational self-esteem. The thought processes related to this external locus-of-hope refer to the capacity and pathways towards goal attainment provided by one's family members and draws attention to how good one's status is with one's family. A positive appraisal of these two constructs concepts is expected to be associated with higher life satisfaction. Based on Du et al.’s (2015) findings, external-family locus of hope was associated with one's relational self-esteem. Thus, the second hypothesis focuses on the mediating role of relational self-esteem:

(b) Relational self-esteem mediates the relationship between external-family locus-of-hope and life satisfaction.

In theory, the indirect effect of external-peer locus-ofhope could be similar to that of external-family locus-ofhope, but Du et al.’s (2015) finding instead showed a negative relationship with life satisfaction. This negative association was mediated by personal self-esteem. As discussed earlier, thinking about how peers help in one's goal attainment seems to call attention to the limitations in one's personal capacities; that is, depending on peers might indicate one is not capable of meeting one's goals. This negative self-appraisal is then associated with lower life satisfaction, as indicated in the third hypothesis:

(c) Personal self-esteem mediates the (negative) relationship between external-peer locus-of-hope and life satisfaction.

There were no indirect effects associated with externalspiritual locus-of-hope found by Du et al. (2015), but they found a direct relationship between external-spiritual locus-of-hope and life satisfaction. They noted that this result contradicted an earlier study with a similar Chinese sample (Du & King, 2013), which they attributed to diversity in religious beliefs among the Chinese, many of whom are atheists. The current study allows to us to explore whether there are also mediated relationships between external-spiritual locus-of-hope and life satisfaction with the two samples that come from countries known to be very religious. Most people in Malaysia and the Philippines consider themselves religious (most Malaysians are Muslim, most Filipinos are Christian); in contrast, the majority of Chinese individuals in our sample in Macau do not have religious affiliations. We do not propose additional hypotheses related to this, although we expect different patterns to emerge between the Macau sample on the one hand, and the Malaysian and Philippine samples on the other.

The preceding point underscores the importance of further validation of Du et al.’s (2015) findings. The three cultural groups in the study are all typically considered collectivist societies that emphasize the interdependent self-construal in cross-cultural comparisons (e.g., Oyserman et al., 2002), but there are also differences such as the religious beliefs of the culture, which could affect the resultant model. We note that there are other known differences among the three samples. Previous studies also describe Malaysians and Filipinos as having lower longterm orientation or being less inclined towards values associated with future rewards than Chinese people (e.g., Hofstede & Minkov, 2010), but we expect that it is common collectivist orientation among the samples that will primarily determine the results.

To summarize, we test three indirect effects with three samples of university students from three cities: Johor Bahru in Malaysia, Macau in China, and Manila in the Philippines. In attempting to replicate Du et al.’s (2015) results, we hope to clarify which mediated pathways linking the personal strength of hope to life satisfaction are specific to particular cultural groups, and which are generalizable across the three groups. Although admittedly limited in cultural diversity, we hope that the results of the study contribute to broader discussions of how cultural dimensions influence the positive impact of personal strengths.

Method

Participants

Participants were 685 university students from three cities (Johor Bahru, Macau, & Manila). The universities in Johor Bahru and Macau were public universities and the one in Manila was a private university. All universities were comprehensive universities offering a range of courses and program; all had selective admission policies. Participants were recruited through the respective research subject pools of each university; all gave their informed consent to participate and were given course credit for their participation. For Johor Bahru (N = 200), the participants' mean age was 17.95 (SD = 3.27) and 62.00 % were female. For Macau (N = 208), the mean age was 18.90 (SD = 1.23), 60.60 % were female. For Manila (N = 277), the mean age was 19.46 (SD = 1.69), 63.20 % were female.

Measures

For the Manila sample, English versions of all the measures were used. For Johor Bahru, the measures were translated from English to Malay following the forward translation process; a professional bilingual translator translated the English scales to Malay, and a bilingual researcher then reviewed the translation. For the Macau sample, previously validated Chinese translations (Du et al., 2015) of the scales were used. Internal consistency/reliability for each of the scales for each sample are reported in Table 1, all of which were .69 or better.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for variables in the three cultural samples.

| Johor Bahru | α | M | SD | Pearson's r | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | ||||

| (1) Internal locus-of-hope | .82 | 3.17 | 0.47 | .64*** | .66*** | .57*** | .47*** | 47*** | .45*** |

| (2) External-family | .87 | 3.36 | 0.51 | .57*** | .56*** | .42*** | .58*** | .44*** | |

| (3) External-peer | .83 | 2.97 | 0.52 | .45** | .25** | .40** | .30*** | ||

| (4) External-spiritual | .92 | 3.35 | 0.68 | .46** | .52*** | .45*** | |||

| (5) Personal self-esteem | .69 | 3.43 | 0.46 | .40*** | .58*** | ||||

| (6) Relational self-esteem | .81 | 3.19 | 0.46 | .49*** | |||||

| (7) Life satisfaction | .84 | 5.39 | 1.10 | ||||||

| Macau | α | M | SD | Pearson's r | |||||

| (1) Internal locus-of-hope | .73 | 2.94 | 0.36 | .30*** | .37*** | .01 | .58*** | .54*** | .47*** |

| (2) External-family | .83 | 2.77 | 0.47 | .46*** | .17* | .23** | .43*** | .31*** | |

| (3) External-peer | .82 | 2.72 | 0.43 | .21** | .14* | .36*** | .27*** | ||

| (4) External-spiritual | .88 | 2.28 | 0.58 | .05 | .06 | .17* | |||

| (5) Personal self-esteem | .83 | 2.78 | 0.46 | .52*** | .50*** | ||||

| (6) Relational self-esteem | .81 | 3.08 | 0.46 | .45*** | |||||

| (7) Life satisfaction | .81 | 4.49 | 1.06 | ||||||

| Manila | α | M | SD | Pearson's r | |||||

| (1) Internal locus-of-hope | .76 | 3.27 | 0.34 | .36*** | .26*** | .11 | .39*** | .42*** | .38*** |

| (2) External-family | .92 | 3.32 | 0.53 | .35*** | .33*** | .13* | .47*** | .33*** | |

| (3) External-peer | .88 | 2.86 | 0.50 | .19** | .01 | .22*** | .15* | ||

| (4) External-spiritual | .96 | 3.45 | 0.68 | .12* | .38*** | .18** | |||

| (5) Personal self-esteem | .82 | 3.66 | 0.47 | .51*** | .44*** | ||||

| (6) Relational self-esteem | .81 | 3.43 | 0.41 | .46*** | |||||

| (7) Life satisfaction | .79 | 5.02 | 1.02 | ||||||

Note. *p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

Locus-of-hope scale. The 40-item scale (Bernardo, 2010) had four subscales: internal, external-family, external-peer, and external-spiritual locus-of-hope. Each subscale had eight items that expressed a thought about goal attainment, and there were eight filler items. Sample items for each subscale are “I meet the goals I set for myself” (internal), “My parents have lots of ways of helping me attain my goals” (external-family), “I have been able to meet my goals because of my friends' help” (externalpeer), “God has many different ways of letting me attain my goals” (external-spiritual). Participants responded used a scale from 1 (definitely false) to 4 (definitely true).

Rosenberg self-esteem scale. The commonly used scale (Rosenberg, 1965) has five positive items (e.g., “I take a positive attitude toward myself”) and five reversescored items. Participants responded using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

Relational self-esteem scale. The scale (Du et al., 2012) had 8 items that measured a sense of self-worth through relationships with significant others (e.g., “I think my family is proud of me”). Participants also responded using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

Satisfaction with life scale. The 5-item scale (E. D. Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) was a cognitive measure of subjective well-being (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”). Responses used a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for each sample, and bivariate correlations were computed to check for multicollinearity. For each sample, a path model that specified the direct and mediated relationships identified in Du et al. (2015) was tested; the path model is summarized in Figure 1. Although not depicted in Figure 1, the four exogenous variables (locus-of-hope subscales) were allowed to correlate with each other, as were the error terms of the two endogenous mediating variables because the two self-esteem factors are assumed to share method variance (cf., Cole, Siesla, & Steiger, 2007). The model was tested in a path analysis (AMOS v24), and the following indexes were considered to determine the suitability of the model: χ2, χ2/df ratio, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), Bollen's incremental fit index (IFI), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). The direct and indirect effects were also examined using bootstrapping analysis, using 10000 bootstrapped samples to test the significance of the indirect effects.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for each sample. Interestingly, the pattern of significant correlations in the Macau sample is consistent with the results found in Du et al. (2015), which also involved a Chinese sample. But the pattern of correlations in the Johor Bahru and Manila samples were different from that in Du et al. (2015), with more significant correlations in Johor Bahru and fewer in the Manila samples compared to the Chinese sample in Du et al. (2015). However, differences in correlations do not necessarily imply different roles of personal and relational self-esteem as mediators of the relationships between locus-of-hope and life satisfaction. The path analyses provide a more direct test of whether Du et al's (2015) model is replicated in the three new cultural simples.

Path analyses

The model tested following the statistical procedures described in the previous section, and in addition the modification indices were considered. There were no suggested modifications for the model with the Macau and Manila samples; however, for the Johor Bahru samples, the modification indices suggested a link between external-spiritual locus of hope and personal self-esteem. This suggestion was considered because it could be theoretically meaningful in consideration of the fact that Malaysians are known to be highly religious, and the link could clarify a possible culture-specific indirect relationship between this locus-of-dimension and life satisfaction. So a second model was tested for the Johor Bahru sample and this was compared to the original model. We summarize the fit indices for each sample before we compare the findings across the three samples.

For Johor Bahru, the original model was found to have an adequate fit with the data: χ2(4) = 11.09, p = .026, χ2/df = 2.77, CFI = .99, TLI = .93, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .09, 90 % CI [.03, .16]. However, the modification indices suggested that a link between externalspiritual locus-of-hope and personal self-esteem will improve the fit. After modifying the model to include this suggested link and to remove the non-significant paths, we tested this revised model and also found a good fit with the data: χ2(7) = 11.40, p = .122, χ2/df = 1.63, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .06, 90 % CI [.01, .11], although the χ2-difference test indicated no statistically significant difference between the original and respecified model (p = .958). For the two other samples, the modification indices did not suggest any changes; the model with the non-significant paths removes had good fit with both the Macau: χ2(6) = 8.92, p = .178, χ2/df = 1.49, CFI = .99, TLI = .97, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .05, 90 % CI [.01, .11] and Manila samples: χ2(6) = 6.67, p = .351, χ2/df = 1.11, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .02, 90 % CI [.01, .08].

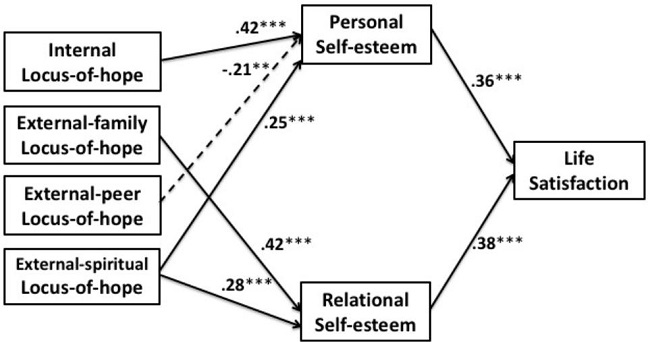

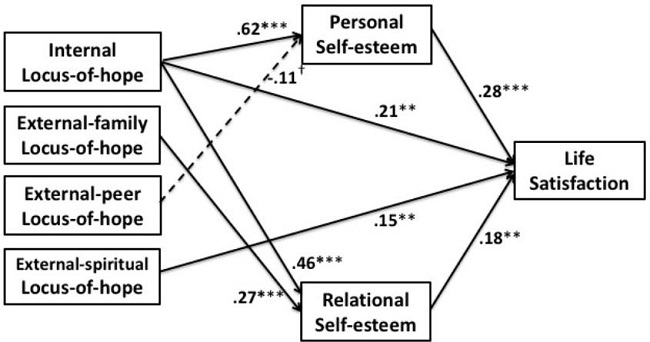

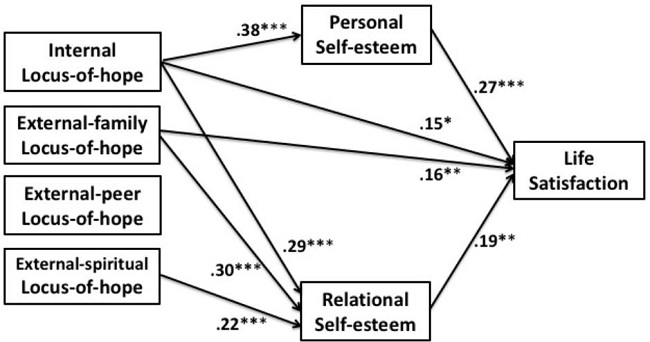

As mentioned above, for each sample, some of the predicted relationships in the model were not significant; so the original model of Du et al. (2015) was not exactly replicated in any of the three samples, even as the model had adequate to good fit in the three samples. The summary of significant paths for each sample are shown in Figures 2 to 4, and we can see that many of the key features of the original model were supported in all three samples. First, personal self-esteem mediated the relationship between internal locus-of-hope and life satisfaction in all three samples. For Johor Bahru, standardized indirect effect = .15, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.08, .26]. For Macau, standardized indirect effect = .26, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.16, .36], and for Manila, standardized indirect effect = .16, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.10, .22]. Second, relational self-esteem mediated the relationship between external-family locus-of-hope and life satisfaction in all three samples. For Johor Bahru, standardized indirect effect = .16, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.08, .26]. For Macau, standardized indirect effect = .05, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.01, .10], and for Manila, standardized indirect effect = .06, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.02, .11].

Figure 2. Summary of significant path coefficients in path analysis of data from Johor Bahru sample. **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 3. Summary of significant path coefficients in path analysis of data from Macau sample. **p < .01, ***p < .001, †p = .058.

Figure 4. Summary of significant path coefficients in path analysis of data from Manila sample. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The two other significant indirect effects in Du et al. (2015) were supported in two of the three cultural samples. Relational self-esteem mediated the relationship between internal locus-of-hope and life satisfaction in the Macau (standardized indirect effect = .26, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.16, .36]), and Manila (standardized indirect effect = .16, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.10, .22]) samples. But for the Johor Bahru sample, internal locus-of-hope was not related to relational self-esteem. Personal selfesteem mediated the negative relationship between external-peer locus-of-hope and life satisfaction in the Johor Bahru (standardized indirect effect = -.08, 95 % bias-corrected CI [ -.16, -.02]) and Macau (standardized indirect effect = -.03, 95 % bias-corrected CI [-.08, -.001]). But external-peer locus-of-hope was not associated with personal self-esteem in the Manila sample. So in summary, 10 of the 12 hypothesized indirect effects from Du et al.’s (2015) model (i.e., four indirect effects for each of the three samples) were supported by the data.

There were country-specific significant indirect effects that were not hypothesized but could still be interpreted as consistent with the general assumptions of model. In particular, the indirect effect external-spiritual locus-of-hope on life satisfaction was mediated by relational self-esteem in the Manila (standardized indirect effect = .04, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.01, .09]) sample and the indirect effect external-spiritual locus-of-hope on life satisfaction was mediated by both personal and relational self-esteem in the Johor Bahru sample (standardized indirect effect = .20, 95 % bias-corrected CI [.11, .29]). We noted that Du et al. (2015) actually predicted a negative indirect effect of external-spiritual locus-of-hope on life satisfaction mediated by relational self-esteem but did not find this to be significant in their Chinese sample, and instead they found direct effects. In contrast, the significant indirect effects found in our current study were both positive.

Discussion

The cross-cultural study was conducted to replicate a mediated model relating hope and life satisfaction in three Asian cultural samples. In doing so, we aimed to explore how cultural factors might relate to how hope, self-esteem, and life satisfaction relate to each other. We first note that two indirect effects found in Du et al. (2015) were replicated in all three samples. In all three cultures, internal locus-of-hope indirectly predicts life satisfaction, mediated by personal self-esteem. This particular finding is one that will also be predicted by the original hope theory (Snyder, 2002) and may be a universal principle about the personal strength of hope. The second replicated indirect effect shows that external-family locus-of-hope predicts life satisfaction but mediated by relational self-esteem. This alternative pathway draws from a form of hope that relates to shared agency with one's family. This form of hopeful thoughts give rise to positive self-worth as it this selfappraisal refers to one's role and responsibilities with significant others. In all three samples from cultures that emphasize interdependent self-construals, this relational self-esteem also relates to life satisfaction. We cannot claim that this path from external-family locus-of-hope to life satisfaction is specific only to interdependent cultures, and future research that tests the same pathways with more individualist cultures can test this proposition.

We note that in two samples (Macau and Manila), internal locus-of-hope was also associated with relational self-esteem, which suggests that hopeful thoughts about one's ability and means to meet life goals also gives rise to positive appraisals of oneself as part of their significant social relations. Consistent with Du et al.’s (2015) findings, internal locus-of-hope is positively related to both personal and relational self-esteem, which suggest that being a person who is capable of working towards one's goals is related to the self-evaluation of being valued in one's social group. Previous studies on academic outcomes suggest that Chinese and Filipino students' achievement strivings and outcomes associated with one's social relationships (Bernardo, 2019; King, Ganotice, & Watkins, 2014). Moreover, attaining one's academic goals further cements relationships (King, McInerney, & Watkins, 2012). But data from the Malaysian sample did not support that pathway, which may suggest that being valued by their social groups is unrelated to thoughts about their own ability to meet their life goals. Another significant indirect effect as found with the Malaysian and Macau sample, where a negative relationship between external-peer locus-of-hope and life satisfaction mediated by personal self-esteem. In this case, thoughts about the role of one's peers in meeting life goals seem to be associated with less positive self-appraisals. Interestingly, no negative association was found between external-family locusof-hope and personal self-esteem, which suggests that the role of one's family members and one's friends in meeting goals have different implications to one's self-worth, with only the latter having a negative implication to self-worth. This result replicated Du et al. (2015) but was not observed with Filipino participants for whom external-peer locus-of-hope was unrelated with any self-evaluation.

Du et al. (2015) found no significant mediated pathways from external-spiritual locus-of-hope and life satisfaction with his Chinese sample, but found a significant direct pathway, and the same was true with our Macau sample. But for the Malaysian and Filipino samples, strong beliefs about the role of their deity in attaining important goals was related to positive self-evaluations, and indirectly to life satisfaction. According to a global survey (Crabtree, 2010), 96% the population in both countries consider their religion to be an important part of their lives. In such cultural contexts, believing in the deity's role in goal attainment is associated with seeing oneself as a good person. In contrast, in the Macau Chinese cultural context where most people are not religious, the same belief relates to life satisfaction but it is not associated with the individuals' positive self-evaluations. This specific result highlights a cultural source that could account for the different results among the three Asian samples, and underscores the importance of referring to specific cultural meanings associated with goal-attainment and self-worth.

The first cultural assumption of the study was that shared or conjoint models of agency relate to different forms of hope among individuals from collectivist cultures. The indirect associations between specific external locus-of-hope dimensions and life satisfaction already provide evidence for how these culturally valued models of agency also contribute to life satisfaction. Interestingly, the external locus-of-hope construct suggests that the personal strength of hope can also be a shared strength for individuals in some cultures. Hope as a personal strength still indirectly predicts life satisfaction in our three Asian samples, but in addition specific forms of shared strengths also predict life satisfaction in these cultures. The notion of shared strengths seems worth exploring further in interdependent cultures where relationships with significant others such as parents, teachers, and peers also tend to predict life satisfaction (Chang, Yang, & Yu, 2017). Recently, other Asian scholars have suggested and developed measures for social hope (Jin & Kim, 2018) which pushes even further the notion of strengths at a collective level.

We acknowledge that our cultural arguments are constrained by some important limitations of our study. Most importantly, we did not actually measure specific cultural sources that can account for different results across the three samples. There might have been other covariates of hope, self-esteem, and life satisfaction that we did not measure or control for in our study. Our research design also involved a cross-sectional survey and a better test of our mediated models should have involved longitudinal data, which could be undertaken in future research studies. As we mentioned earlier, our attempt to do a cross-cultural replication of the mediated model involved all Asian cultures and a stricter test of the model should have involved a wider variety of cultures from various continents. Recently, positive outcomes have been associated with external locus-of-hope dimensions in North American samples (Munoz, Quinton, Worley, & Helman, 2018; Wagshul, 2018). Indeed, it will be most interesting to see whether the findings related to the external locus-of-hope mediated pathways will be replicated in more individualist cultures.

These limitations of our study notwithstanding, we believe our results clearly point to how established theories and empirical findings on the personal strength of hope need to be expanded to give due importance to how individuals from different cultures might construct the meaning of concepts like agency in goal-pursuit and self-worth. In psychologists' attempts to better understand the resources that allow individuals to flourish, it might be worth remembering that these resources do not just comprise personal strengths, but also important shared strengths).