INTRODUCTION

The pharmacist is the most commonly approached health professional for advice on natural products.1 However, an American College of Clinical Pharmacists White Paper in 2017 reported that pharmacists’ self-perceived preparedness for discussing natural products remained low, despite regular questions from patients.2 Simply discounting the value of natural products can negatively impact the patient-pharmacist relationship, especially when patient self-belief in natural products is strong.2 Systematic reviews of natural products may be a valuable source of information for practicing pharmacists because they efficiently describe the nature of the data available in a field and can reconcile conflicting information for readers.3,4

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) ranges from the simple deposition of fats to steatosis-induced hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and in some cases hepatocellular carcinoma.5 It is estimated that 20%-30% of adults in Western countries and 5%-18% in Asia have NAFLD.5 NAFLD is very common in overweight and obese individuals as well as people with metabolic syndrome or type-2 diabetes mellitus.5 NAFLD is the second most common reason for liver transplantation and patients with NAFLD have a high risk of developing cardiovascular disease.5

Weight loss due to reduced caloric intake or exercise are recommended therapies in patients with NAFLD regardless of severity.6 In the 2018 guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, pharmacologic therapy is reserved for patients with a more severe form of NAFLD called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH; >5% liver fat content and inflammation with hepatocyte injury).6 While pioglitazone is an option for patients with biopsy proven NASH, the other options including metformin, ursodeoxycholic acid, and omega-3 fatty acid are not recommended.6 The glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists do not have enough data to recommend them in NASH.6 Vitamin E may be considered but the risks should be discussed with each patient before starting therapy.6,7 Vitamin E has evidence of reduced steatosis and decreases in liver function test values but it has no effect on hepatic fibrosis and there are concerns over vitamin E’s impact on overall mortality and prostate cancer risk.6,7 This suggests that an alternative natural product with similar benefits to vitamin E but without the potential risks could be important in the treatment of this common and dangerous condition.

Turmeric (Curcuma Longa) has active constituents in its rhizome called curcuminoids with the most prominent curcuminoid called curcumin.8 In in vitro and animal studies, turmeric has demonstrated potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic properties as well as insulin sensitizing effects.8 As such, it might hold promise in the treatment of patients with NAFLD.

In this systematic review, we assess the impact of turmeric or its curcumin extract in patients with NAFLD on indices of liver damage or NAFLD severity.

METHODS

Search Strategy

We performed search strategies within PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central using the MeSH or free text terms “((turmeric OR Curcumin OR Curcuma OR Curcuminoids) AND (NAFLD OR Fatty Liver OR Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis))” from the earliest possible time to 12/17/18. In addition, we conducted backwards citation tracking (a manual literature search of the reference lists of included articles for missing trials).

After de-duplication of citations from the three datasets, two independent investigators applied inclusion criteria to each citation with disagreements resolved via consensus.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were framed in the Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome, Study Design (PICOS) format. Population: Patients with NAFLD. Intervention: Use of turmeric or any curcumin extract (not to be combined with other potentially effective substances except those used to enhance bioavailability).3 Control: Control groups were not required if baseline comparisons were available and acceptable control groups could contain active therapy, placebo, or no therapy. Outcomes: Evaluable data for alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), NAFLD severity via ultrasound, or liver biopsy results. Study Design: Controlled or uncontrolled trials were permissible but observational studies, case reports, and case series were excluded.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers’ independently extracted data from the literature in this review with disagreements resolved via consensus. The extracted data included the following: author, year, geographic location, intervention, comparator, dose, duration, blinding, sample size, gender (M/F), age, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentration, NAFLD ultrasound grade, and liver biopsy findings.

RESULTS

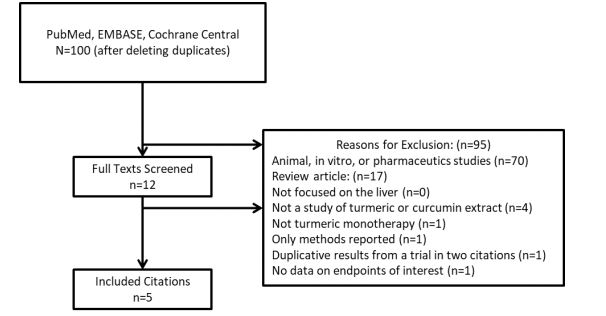

The number of citations, trials ultimately included, and the reasons for exclusion for the other citations are provided in Figure 1.9 10 11 12 13-14 Authors of the originally included studies were contacted for missing data via email, where possible. Studies were assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool with all identified potential biases described in the narrative text below.

Five trials met our inclusion criteria with methodologic and demographic information provided in Table 1.9 10 11 12 13-14 Panahi 2018 was a single arm and open label trial.11 All of the other included trials specified that they were randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled.9,10,12 13-14 However, the Panahi 2017 trial allocated therapy on an alternating basis (Bottle A, then B, then A, then B, etc) instead of performing true randomization.12 Specifics of the other trials’ randomization strategies were not provided.9,10,12 13-14 The evidence of incomplete data is indeterminate in all trials and there was no evidence of selective reporting except in the trial by Chirapongsathorn 2012 where 53 patients were reportedly enrolled but only 20 had outcome data reported.9,10,12 13-14 Chirapongsathorn 2012 is only available in abstract form and the length of time without a resulting publication suggests the possibility of methodological issues.9,10

Table 1. Overview of Included Trials.9 10 11 12 13-14

| Name/Year | Chirapongsathorn, 2012 | Panahi, 2018 | Panahi, 2017 | Rahmani, 2016 | Navekar, 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design, Sample Size | DB, PC; n=20 | SA, OL; n=36 | DB, PC; n=87 | DB, PC; n=80 | DB, PC; n=46 |

| Intervention | Curcumin (Dose NR) | Curcumin 1500mg/day | Curcumin 1000mg/day | Curcumin 500mg/day | Turmeric 3000mg/day |

| Duration | 6 months | 8 weeks | 8 weeks | 8 weeks | 12 weeks |

| Age | 53-57 years | 49 years | 45-47 years | 46-49 years | 40-42 years |

| Gender | 55% Male | NR | 59% Male | 48% Male | 43% Male |

| Country | Thailand | Iran | Iran | Iran | Iran |

DB = double blinded, OL = open label, NR = not reported, PC = placebo controlled, SA = single arm (no control group)

Given the heterogeneous forms and doses of curcumin and turmeric, different durations of therapy, and differences in baseline NAFLD severity scores and concentrations of ALT and AST, we did not believe that statistically pooling results was prudent.9,10,12 13-14 None of the trials had data on liver fibrosis.9,10,12 13-14

The trial by Chirapongsathorn 2012 was difficult to interpret because it was only available in abstract form and it had typographical issues.9 They enrolled 53 patients in Thailand but only reported data on 20 patients. These patients were randomized to receive curcumin (at an unspecified dose or formulation) or placebo. The mean differences for ALT [-9.11 (95%CI, -21.49 to 3.27)] and AST [-9.8 (95%CI, -20.42 to 0.82)] were nonsignificantly lower when curcumin was compared to placebo.9,10

Outcome data for all the other trials are provided in Table 2.11 12 13-14 The first trial by Panahi 2018 allocated all 36 Iranian patients with NAFLD to curcumin (500mg three times daily) or placebo for 8 weeks.11 The curcumin extract was a phytosomal formulation that contained a complex of curcumin and soy phosphatidylcholine (Meriva®, Indena Corp, Milan, Italy). This means the pure curcuminoid content was 20% of the total or 300mg a day. All of the patients were analyzed. The use of curcumin therapy reduced ALT, AST, and NAFLD severity versus baseline (p<0.001 for each comparison).11

Table 2. Impact of turmeric or curcumin extracts on outcomes.11 12 13-14

| Turmeric/Curcumin | Placebo | Active vs. placebo change from baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panahi 2018 (n=36) | |||||

| ALT | Baseline: 40.7 (SD 15.0) | -- | -- | ||

| Final: 22.0 (SD 7.2)^ | -- | -- | |||

| AST | Baseline: 35.4 (SD 11.9) | -- | -- | ||

| Final: 22.6 (SD 7.2)^ | -- | -- | |||

| NAFLD | Before Grade 0: 0.0% |

After^

11.1% |

-- | -- | -- |

| Grade 1: 50.0% | 36.1% | -- | -- | ||

| Grade 2: 38.9% | 52.8% | -- | -- | ||

| Grade 3: 9.1% | 0.0% | -- | -- | ||

| Panahi 2017 (n=87) | |||||

| ALT | Baseline: 35.46 (SD 22.97) | Baseline: 36.81 (SD 24.32) | -10.61 (SD 15.49) vs. +4.51 (SD 7.40)# | ||

| Final: 24.85 (SD 12.84)^ | Final: 41.33 (SD 23.97)* | ||||

| AST | Baseline: 27.63 (SD 11.35) | Baseline: 27.44 (SD 10.01) | -6.95 (SD 7.47) vs. +3.79 (SD 6.43)# | ||

| Final: 20.68 (SD 6.65)^ | Final: 31.23 (SD 12.80)* | ||||

| NAFLD Severity | Before Grade 0: 0.0% |

After^

34.1% |

Before Grade 0: 0.0% |

After *

2.3% |

NAFLD severity improved in 75% vs. 4.7%#

NAFLD severity worsened in 4.5% vs. 25.6%# |

| Grade 1: 38.6% | 47.7% | Grade 1: 39.5% | 23.3% | ||

| Grade 2: 52.3% | 13.6% | Grade 2: 44.2% | 48.8% | ||

| Grade 3: 9.1% | 4.5% | Grade 3: 16.3% | 25.6% | ||

| Rahmani 2016 (n=77) | |||||

| ALT | Baseline: 39.07 (SD 19.79) | Baseline: 30.35 (SD 13.97) | -2.99 (SD 47.38) vs. -1.62 (SD 12.30)# | ||

| Final: 36.08 (SD 46.58)^ | Final: 28.72 (SD 10.93) | ||||

| AST | Baseline: 28.88 (SD 10.60) | Baseline: 32.05 (SD 17.64) | -5.04 (SD 6.49) vs. +2.02 (SD 11.79)# | ||

| Final: 23.84 (SD 7.83)^ | Final: 34.07 (SD 18.73) | ||||

| NAFLD Severity | Before Grade 0: 0.0% |

After^

15.8% |

Before Grade 0: 0.0% |

After 0.0% |

NAFLD severity improved in 78.9% vs. 27.5%#

NAFLD severity worsened in 0.0% vs. 17.5%# |

| Grade 1: 25.6% | 71.1% | Grade 1: 32.5% | 35.0% | ||

| Grade 2: 48.7% | 13.2% | Grade 2: 55.0% | 60.0% | ||

| Grade 3: 25.6% | 0.0% | Grade 3: 12.5% | 5.0% | ||

| Navekar 2017 (n=42) | |||||

| ALT | Baseline: 23.07 (Range 9-112) | Baseline: 23.67 (Range: 10-125) | Mean difference = -2.25 (95% CI: -8.96 to 4.45) | ||

| Final: 19.87 (Range 10-51) | Final: 22.85 (Range 10-60) | ||||

| AST | Baseline: 24.00 (SD 11.59) | Baseline: 24.33 (SD 13.69) | Mean difference = +0.49 (95% CI: -2.98 to 3.97) | ||

| Final: 24.14 (SD 8.90) | Final: 24.04 (SD 5.40) | ||||

| NAFLD Severity | Before Grade 0: 0.0% |

After 0.0% |

Before Grade 0: 0.0% |

After 0.0% |

No differences noted between groups |

| Grade 1: 57.1% | 66.7% | Grade 1: 47.6% | 66.7% | ||

| Grade 2: 42.9% | 33.3% | Grade 2: 52.4% | 33.3% | ||

| Grade 3: 0.0% | 0.0% | Grade 3: 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

^Denotes significant intragroup DECREASES from baseline.

*Denotes significant intragroup INCREASES from baseline.

#denotes significant intergroup differences between groups. -- = No Control Group/Not Applicable, NG = Not Given.

Panahi 2017 alternately allocated 102 Iranian patients with NAFLD to receive the same curcumin product as Panahi 2018 (Meriva®, Indena Corp, Milan, Italy) but at a lower dose (500mg capsules twice daily) or placebo for 8 weeks.12 The pure curcuminoid content in this trial was 200mg a day. Six patients in the curcumin group and 9 in the placebo group discontinued therapy for self-perception of lack of benefit so only 87 patients were analyzed. The use of curcumin therapy reduced ALT, AST, and NAFLD severity versus baseline but worsened with placebo therapy over time. This led to marked differences between the curcumin and the placebo groups for these variables (P<0.001 for each comparison).12

Rahmani 1996 randomized 80 patients with NAFLD in Iran to receive curcumin (500mg capsules twice daily) or placebo or 8 weeks.13 The capsules were described as an amorphous dispersion preparation comprising 70mg of pure curcuminoids but the manufacturer or the process was not further described. As such, the pure curcuminoid dose was 140mg daily. Three patients withdrew from the curcumin group due to stomach pain/nausea versus no patients in the placebo group. There was no intention to treat analysis with data analysis limited to the 77 subjects completing the trial.13 Like the Panahi 2017 trial, patients in Rahmani 2016 had significant reductions in ALT, AST, and NAFLD severity grade when treated with curcumin versus baseline and had significantly better effects than with placebo (p=0.001, p=0.002, p<0.001, respectively).12,13 However, in the placebo group the ALT, AST, and NAFLD severity grade did not continue to worsen versus baseline like with Panahi 2017 (p=0.409, p=0.284, p=0.622, respectively).13

Navekar 2017 randomized 46 Iranian patients with NAFLD to receive turmeric (3000mg daily given as six 500mg capsules) or placebo for 12 weeks.14 In this trial, locally purchased turmeric rhizome was washed, dried, and cut into small pieces. The pure curcuminoid dose is unknown. Two patients in each group did not complete the study for “personal reasons” and no intention to treat analysis was performed, leaving 21 patients per group to be analyzed. In this trial, turmeric did not reduce AST or NAFLD severity grade versus baseline and did not significantly reduce ALT versus baseline. No differences occurred between the turmeric and placebo groups for any of these three outcomes.14

DISCUSSION

In contrast to Panahi 2017 and Rahmani 2016, Navekar 2017 did not significantly reduce ALT, AST, or NAFLD severity grade versus placebo.9-14 The active group in Navekar 2017 also did not reduce ALT, AST, or NAFLD severity grade versus baseline, unlike Panahi 2018, Panahi 2017, or Rahmani 2016. The first potential explanation for these findings is related to differences in the severity of disease. ALT and AST are validated measures of ongoing liver damage with normal ranges of 1 to 27u/L in most commercial laboratories.5 Unlike the other trials, in Navekar 2017 the ALT and AST concentrations at baseline were only elevated toward the upper end of the normal range, not exceeding that range.9 10 11 12 13-14 NAFLD severity grade is determined by ultrasound with hepatic steatosis graded from 0 (lack of liver fat accumulation) up to 3 (severe increase in echogenicity with markedly impaired visualization of the diaphragm, intrahepatic vessel borders, and posterior portion of the right hepatic lobe).5 In Panahi 2018, Panahi 2017, and Rahmani 2016, some patients had NAFLD severity grade 3 but in Navekar 2017, people only had grade 1 or 2 disease.11 12 13-14 A second potential explanation is related to the form and dosage of the active product being used in different trials.9 10 11 12 13-14 Panahi 2017 and Rahmani 2016 used 500 mg of curcumin extracts dosed twice daily (1000mg daily) and Panahi 2018 used 500mg three times daily (1500mg daily) while Navekar 2017 used locally purchased raw turmeric rhizomes which were washed, dried, and cut into small pieces and dosed at 3000 mg once daily.11 12 13-14 It is known that the bioavailability of curcumin from raw turmeric is very low.8

In November 2018, a meta-analysis of trials was conducted assessing the impact of curcumin on ALT and AST in patients with NAFLD.10 The meta-analysis only discovered the trials by Chirapongsathorn 2012 and Rahmani 2016 and found no significant mean difference between the curcumin and placebo group for ALT [-6.02 (95%CI: -15.61 to 3.57)] but did find significant differences for AST [-7.43 (95%CI: -11.31 to -3.54)]. In light of the many instances of clinical and methodologic heterogeneity with the trials, we disagree with their decision to meta-analyze this data. Their conclusion is that curcumin is effective in lowering AST levels in NAFLD and that there was high evidence supporting the use for curcumin lowering ALT and AST concentrations in NAFLD patients.10 We disagree that with only two trials, one of which providing no information into the dose of curcumin used and with a very large withdrawal rate, that this is a correct determination.

Given the available data, curcumin is a promising but not proven therapy for NAFLD at this time and the role of turmeric is unclear. None of the trials assessed for the impact of turmeric or curcumin on liver fibrosis.9 10 11 12 13-14 This is a critical omission since other therapies that are not recommended for use in NAFLD such as metformin also reduce ALT and AST but were unable to impact liver fibrosis.6 In addition, none of the trials had patients mean ALT or AST concentrations greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal so whether the reductions in the liver function tests would be consistent or accentuated in patients with more severe NAFLD is unknown. It is also unknown how the magnitude of these reductions in liver function tests would diminish the risk in patients with more severe manifestations of NAFLD such as NASH.5,6,9 10 11 12 13-14 There are other methodological limitations such as small sample sizes, relatively short durations of follow-up, and lack of intention to treat analyses in these trials.9 10 11 12 13-14 There are also variations in the curcuminoid content of the products, different dosing schedules, and insufficient probing of safety endpoints in these trials.9 10 11 12 13-14 While these trials were said to be randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled, the specifics were not provided to verify whether the trials actually conformed to these factors.9,12 13-14 Panahi 2017 was the only trial that gave enough information to assess for randomization and this trial did not meet the definition of true randomization.12

There is an ongoing clinical trial by Jazayeri-Tehrani and colleagues that is assessing the impact of curcumin on insulin resistance, lipids, and inflammatory mediators but those results, while desirable, will not fill the evidence gap needed to determine curcumin’s place in therapy.15 A larger controlled trial with longer duration of follow-up assessing a standardized commercially available product that assesses ALT, AST, NAFLD severity, liver fibrosis, and safety endpoints is needed.