Cyber dating violence among adolescents encompasses all aggressive and coercive behaviours targeted at one's current or ex romantic partner using smart devices, the Internet, and the social media (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021; Zweig et al., 2014).

Interest in this new form of online violence has resulted in the development of measurement instruments with diverse characteristics. Recent systematic reviews (Kim & Ferraresso, 2022; Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022; Rocha-Silva et al., 2021; Rodríguez-deArriba et al., 2021) have confirmed that although progress has been made in developing validated measures (Calvete et al., 2021; Lara, 2020; Morelli, et al., 2018), some instruments have yet to report their psychometric properties (Rodriguez-deArriba et al., 2021).

In terms of the operationalisation of different types of violence, the most studied are verbal and emotional abuse and cyber control (Borrajo et al., 2015; Cava & Buelga, 2018; Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2017). Verbal/emotional cyber dating violence refers to behaviours designed to hurt one's romantic partner using insults, humiliation, and blackmail (Calvete et al., 2021; Morelli et al., 2018; Reed et al., 2017). Cyber control refers to the surveillance, monitoring and control of the partner's online and social media activities (Cava & Buelga, 2018; Reed et al., 2017; Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2017). Borrajo et al. (2015) developed one of the first instruments designed to assess cyber dating violence among Spanish young adults, distinguishing between two behavioural dimensions: direct aggression and control. This initial measure was later validated in other cultures, including Brazil (Cavalcanti et al., 2020), Portugal (Caridade et al., 2020) Mexico (Hidalgo-Rasmussen et al., 2020) and Chile (Lara, 2020). The scale has also been used with Spanish adolescents (Machimbarrena et al., 2018; Quesada et al., 2018), although validation analyses are required to adapt it to this population (Redondo et al., 2022). The instrument developed by Cava and Buelga (2018) was validated in the adolescent population and proposed two dimensions, named cyber aggression (which includes behaviours such as threats and insults) and cyber control. In terms of prevalence, the rates reported vary widely. According to some studies, control is more prevalent than verbal/emotional violence, with prevalence rates of approximately 50% for cyber control and 10% for verbal/emotional (Cava & Buelga, 2018). However, other authors, such as Smith-Darden et al. (2017) , have reported the opposite, finding higher rates of verbal/emotional violence (33%) than of cyber control (17%). For their part, Reed et al. (2017) found similar rates for both direct forms of aggression (approximately 45%-50%).

Sexual cyber dating violence, understood as coercive behaviours of a sexual nature, ranging from the sending of sexually explicit material without consent, to consensual sharing of intimate explicit material of one's romantic partner, or online sexual harassment, has been much less widely studied (Kim & Ferraresso, 2022; Rodríguez-deArriba et al., 2021). To date, five instruments have included this type of violence as an independent behavioural dimension (Fissel et al., 2022; Reed et al., 2017; Smith-Darden et al., 2017; Watkins et al., 2018; Zweig et al., 2013), although these instruments have only been validated in the adult population (Fissel et al., 2022; Watkins et al., 2018). In relation to prevalence rates, previous studies conclude that sexual cyber violence is less frequent than other types of violence, with rates being between 2.7% and 16.9% for aggression and between 7.8% and 32.2% for victimisation (Reed et al., 2017; Zweig et al., 2013).

As Brown and Hegarty (2018) point out, one challenge in measuring cyber violence is the fact that the specific context of the aggressive act must be considered. In this sense, the public-private dimension of the aggression seems to influence the severity of the actions (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022) Previous studies confirm this thesis since adolescents perceive that cyber aggressions perpetrated in front of an audience are perceived as more serious and harmful than those that occur in the intimate context of the couple (Melander, 2010; Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2022; Stonard, 2020). Nevertheless, existing validated measures fail to take this characteristic into consideration (Cava & Buelga, 2018; Morelli, et al., 2018), which may influence the prevalence rates found (Brown & Hegarty, 2018).

Finally, different types of scales have been used, although the majority are multi-item scales that enable researchers to analyse a broad spectrum of behaviours. This category ranges from single-dimensional 34-item scales (Watkins et al., 2018) to scales with diverse dimensions composed of 10 or more behaviours (Borrajo et al., 2015; Zweig et al., 2014). In contrast, other instruments assess cyber violence using a single item (Barter et al., 2017; Stonard, 2020), thereby preventing researchers from determining which specific behaviours are more characteristic or more severe (Menesini et al., 2011).

The present study aims to further this line of research by developing, validating, and refining a new assessment measure for cyber dating violence among adolescents. Specifically, the aims of the present study were: 1) To develop and validate a new instrument for assessing cyber dating aggression and victimisation among adolescent couples in three dimensions: verbal/emotional, control and sexual; 2) To identify the most representative and discriminating behaviours on each scale, based on Item Response Theory; 3) To test a new refined version of the instrument; and 4) To determine the prevalence of the different dimensions of cyber teen dating violence.

To date, only one other study has sought to identify the most salient items pertaining to each type of cyber dating violence among the adult population (Fissel et al., 2022). The present study aims to be one of the first to do the same in relation to the adolescent population.

Method

Participants

Participants were 600 students aged between 14 and 18 years (M = 15.54; SD = 1.22) from five public high schools in Seville and Córdoba, with medium and medium-low economic, social and cultural status. Of these initial participants, only those who had been in a romantic relationship over the past year and had an Internet-enabled mobile telephone during that time were selected for our study. The final sample comprised 307 adolescents aged between 14 and 18 years (M = 15.57; SD = 1.26). Of these, 46.9% were boys (n = 144), 51.8% girls (n = 159), 1% non-binary (n = 3), and 0.3% preferred not to say (n = 1). In terms of education level, 31.6% (n = 97) were in the third year of secondary school (ESO), 45.3% (n = 139) were in the fourth year of ESO, 8.1% (n = 25) were in the first year of the Spanish Baccalaureate (SB) and 11.4% (n=11) in the second year of the SB. The 74.1% (n = 223) defined themselves as heterosexual, 20.6% (n = 62) as bisexual, 3% (n = 9) as homosexual, 1.7% (n = 5) said they did not know and 0.7% (n = 2) as asexual.

Instruments

The instrument was developed in 4 phases: a) Literature review; b) Focus groups with young adults; c) Review by experts; and d) Creation of the final instrument.

a) Literature review

We reviewed the extant literature on adolescent cyber dating violence with the aim of identifying the theoretical dimensions, the most representative behaviours of the construct and the principal limitations of previous studies (Kim & Ferraresso, 2022; Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022; Rodríguez-deArriba et al., 2021). We also reviewed measures of face-to-face dating violence to adapt certain behaviours to the online context (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006; Foshee, 1996). This analysis returned 34 behavioural items that were grouped into three theoretical dimensions: verbal/emotional, control and sexual.

b) Focus groups with young adults

During the second phase, we organised 6 focus groups with psychology, education, and agricultural engineering undergraduates. Participants were 14 boys and 30 girls aged between 18 and 23 years. Participants were given the list of 34 items and were asked to state their opinion in terms of representativeness, severity and perceived types. Participants identified public forms of violence and those that included multimedia content as being the most serious, whereas those entailing control and surveillance were identified as the most frequent. The classification of the items resulted in the differentiation between sexual and non-sexual forms, with those referring to cyber control being the ones identified most clearly. Participants recommended eliminating some items, arguing that they were unrealistic or obsolete in the online environment (e.g., ‘Threatening to damage or break something belonging to one's partner') and recommended using the verb ‘pressuring' instead of other more ambiguous terms such as ‘asking'.

C) Review by experts

Based on the opinions expressed by the young adults, the 34 original items were transformed into 28 (Table 1). Some items were divided into two, depending on the audience or witnesses of the aggression (e.g., public insults vs. Private insults), some were eliminated altogether, and others were grouped into a single item, such as items describing different means of threatening one's partner. The resulting items were reviewed by expert psychologists, who made improvement suggestions and adapted some linguistic expressions. The items were then written using neutral wording so they could be used as double items for both aggression and victimisation. We also ensured that all three behavioural dimensions were represented and that each dimension included public and private behaviours.

Table 1. List of items

| Verbal/emotional cyber dating violence |

|---|

| 1. Insulting, belittling or making hurtful comments to one's partner through private messages (e.g., WhatsApp chat or private messages on Instagram) [Insultar, menospreciar o hacer comentarios dañinos a la pareja a través de mensajes privados (p.e., en chat de WhatsApp o por mensajes privados en Instagram)] |

| 2. Publically insulting, belittling or making hurtful comments to one's partner (e.g., in posts, photos, or group conversations) [Insultar, menospreciar o hacer comentarios dañinos a la pareja de manera pública (p.e., en publicaciones, fotos, o conversaciones grupales)] |

| 3. Blackmailing one's partner using technology or the social media to get them to do something they don't want to do [Chantajear a la pareja usando las tecnologías o redes sociales para conseguir que hiciera algo que no quería hacer]** |

| 4. Using technology or social media to threaten one's partner with physical harm [Utilizar las tecnologías o redes sociales para amenazar con hacer un daño físico a la pareja] |

| 5. Insulting one's partner through technology or the social media, using derogatory expressions such as lesbian, faggot, slut, etc. [Insultar a través de las tecnologías o redes sociales a la pareja con expresiones despectivas como lesbiana, marica, guarra, etc.]** |

| 6. Reproaching one's partner for something that happened in the past through technology or the social media [Reprochar a la pareja algo que ha ocurrido en el pasado a través de las tecnologías o redes sociales] |

| 7. Using technology or the social media to make one's partner jealous [Utilizar las tecnologías o redes sociales para poner celosa a la pareja] |

| 8. Spreading rumours or ridiculing one's partner through technology or the social media [Difundir rumores o ridiculizar a la pareja a través de las tecnologías o redes sociales] |

| 9. Sharing a private photograph or video of one's partner to ridicule him/her through technology or the social media [Difundir una fotografía o vídeo privado de la pareja para ridiculizarla a través de las tecnologías o redes sociales]** |

| Control cyber dating violence |

| 10. Pressuring one's partner to delete or block certain people on the social media [Presionar a la pareja para que borrara o bloqueara a ciertas personas en redes sociales] |

| 11. Deleting or blocking certain people on one's partner's social networks [Borrar o bloquear a ciertas personas en las redes sociales de la pareja] |

| 12. Deleting one or more accounts, posts or photos from one's partner's social media accounts or phone [Borrar una o varias cuentas, publicaciones o fotos en Redes Sociales o del teléfono de la pareja] |

| 13. Repeatedly calling/sending many messages in a row to one's partner to find out where they are, what they are doing or who they are with [Llamar repetidamente/enviar muchos mensajes seguidos a la pareja para conocer dónde está, lo que está haciendo o con quién está] |

| 14. Repeatedly contacting one's partner's friends or family members to find out where they are, what they are doing or who they are with [Contactar repetidamente con amigos o familiares de la pareja para conocer dónde está, lo que está haciendo o con quién está la pareja]** |

| 15. Pressuring one's partner in order to get their passwords to their personal accounts, even though they do not want to share them [Presionar para conseguir la contraseña de las cuentas personales de la pareja, incluso sabiendo que la pareja no quería compartirlas] |

| 16. Logging in with one's partner's password to check their social media activity (such as private messages with other people) without their permission [Iniciar sesión con la contraseña de la pareja para revisar su actividad en redes sociales (como mensajes privados con otras personas) sin su permiso] |

| 17. Creating a fake account on a social network in order to add one's partner and test her/him [Crear una cuenta falsa en una red social para añadir a la pareja y ponerla a prueba] ** |

| 18. Looking at private information on one's partner's mobile phone (such as private messages or call history) without permission [Mirar información privada del móvil de la pareja sin permiso (como mensajes privados o historial de llamadas)] |

| 19. Constantly checking one's partner's social media activity (such as the time of their last connection, or if there are any new posts) to know what they are doing and with whom [Revisar constantemente la actividad en redes sociales de la pareja (como la hora de la última conexión, o si hay publicaciones nuevas) para saber qué está haciendo y con quién]** |

| Sexual cyber dating violence |

| 20. Making unwanted sexual comments, jokes, or gestures to one's partner through technology or the social media [Hacer comentarios, bromas o gestos sexuales no deseados por la pareja a través de las tecnologías o redes sociales] |

| 21. Spreading false rumours about one's partner's sexual behaviour through technology or the social media [Difundir falsos rumores sobre el comportamiento sexual de la pareja a través de las tecnologías o redes sociales] |

| 22. Sending intimate photographs or videos through technology or the social media showing some parts of one's own body when one's partner did not want to see them [Enviar fotografías o vídeos propios sugerentes enseñando algunas partes del cuerpo cuando la pareja no quería verlas a través de las tecnologías o redes sociales] |

| 23. Taking erotic or sexual photographs or videos of one's partner without their permission [Hacer fotografías o vídeos eróticos o sexuales de la pareja sin su permiso]* |

| 24. Pressuring one's partner to send a photo showing an intimate area of his/her body [Presionar a la pareja para que envíe una foto enseñando alguna zona íntima de su cuerpo] |

| 25. Pressuring one's partner to have sex by messages, emails or instant messages (WhatsApp), etc., knowing that they do not want to [Presionar a la pareja para tener sexo enviándole mensajes, correos electrónicos, mensajes instantánea (WhatsApp), etc., sabiendo que la pareja no quería] |

| 26. Posting or sharing a sexual photo or video of one's partner without permission [Publicar o compartir sin permiso una foto o un vídeo de la pareja de contenido sexual]* |

| 27. Pressuring or using threats to convince one's partner to pose in front of a webcam in order to take pictures of them [Presionar o amenazar a la pareja para que posara frente a la webcam y hacerle fotos]* |

| 28. Asking one's partner for photos or videos of a sexual nature when she/he was under the influence of alcohol [Pedir fotos o vídeos de carácter sexual a la pareja aprovechando que ésta estaba bajo los efectos del alcohol] |

Note: * Items eliminated due to low frequency; ** Items eliminated following the IRT analysis.

The 28 items corresponded to three dimensions:

Verbal/emotional cyber dating violence (items 1-9): public and private aggressive behaviour aimed at hurting one's partner using insults, humiliation, blackmail or by sharing information.

Control cyber dating violence (items 10-19): abusive use of technology to monitor, control and decide about one's partner's online and social media activities.

Sexual cyber dating violence (items 20-28): non-consensual and intimidating behaviour that violates one's partner's sexual freedom and intimacy, including the trafficking of multimedia content.

d) Creation of the final scale

The final Cyber Dating Violence Instrument for Teens (CyDAV-T) comprised 28 double items (for both aggression and victimisation) rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = ‘This has never happened to me' to 4 = ‘This almost always happens to me', which measures the frequency with which respondents have experienced the behaviour described over the past year.

Dating status and the use of technology were controlled for through the following questions: ‘Do you have or have you had a romantic partner over the past year?', (response options being 0 = ‘No' and 1 = ‘Yes'); and ‘Did you have an Internet-enabled mobile telephone and profiles of social media (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, etc.) during that time?', (response options: 1 = ‘I had neither of these two things', 2 = ‘I had an Internet-enabled mobile telephone but no social media profiles'; 3 = I had an Internet-enabled mobile telephone and at least one social media profile').

To analyse the instrument's evidence of criterion and convergent validity, we included the online moral disengagement scale (Paciello et al., 2020) and the Non-Consensual Sharing (NCS) scale, that measures the non-consensual re-sending of other people's intimate sexual content (Walker et al., 2021). Moral disengagement is closely linked to the explanation of violent online phenomena (Lo Cricchio et al., 2021) and NCS is considered a specific type of sexual cyber aggression (Walker & Sleath, 2017). The mean for the scales was calculated.

Procedure

An accessibility-based sampling technique was used for this study. To recruit participants for the focus groups, the members of the research team posted notices in the first-year classrooms of the faculties of Psychology, Education and Engineering informing about the study aims and the conditions for participation. The decision was made to interview first-year university undergraduates because they were the closest in age to the adolescent population, and because gaining informed consent was simpler with these participants, since they were all legal age.

To recruit adolescent participants, an e-mail describing the aims of the study and the participation conditions was sent to a list of public schools known by the research team. Researchers then met with representatives of any interested schools. Once an agreement had been reached, their participation was approved by the School Board and informed consent was requested from families. Those students who agreed to participate completed the questionnaire during class time and in the presence of teachers. The questionnaire was available in both pen and paper and online format, with each school choosing one of the two options in accordance with its COVID-19 regulations. Participants were informed by the research team of the aims of the study and the voluntary nature of their participation and were reassured that any information provided would be treated confidentially. The study was approved by the ZZ's Ethics Committee.

Data Analysis

Given the high degree of non-normality of the item distribution, we dichotomised the answers following the recommendations of previous studies (Menesini et al., 2011): 0 (no involvement) and 1 (involvement). Descriptive item and scale analyses were performed with SPSS26.

First, items with a frequency of involvement less than 3% in the aggression and victimisation scales were eliminated due to their low representativeness in the sample. Second, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) for aggression and victimisation were conducted on a theoretical three-factor starting model (Byrne, 2013) using MPlus8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017). Delta parameterisation and the weighted least squared mean variance (WLSMV) estimator were used. The recommended fit indexes for structural equation models (Ferrando et al., 2022; Kline, 2015) were reported: χ 2 of the model, CFI (Comparative Fit Index) to explore the comparative fit of the proposed solution with respect to the null independence model, and RMSEA (Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation) to indicate the relative fit of the model with respect to its complexity. The optimal values for each are CFI >.95 and RMSEA <.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1998; Kline, 2015).

Next, a two-parameter IRT model was developed with the IRTPRO application to examine the items quality and representativeness. This analysis provides the discrimination (a) and difficulty (b) parameters of each of the items in the latent factor. The item discrimination parameter indicates how well an item may differentiate people with different levels of ability, with the most discriminating items being those with the highest scores (De Ayala, 2013). The item difficulty parameter represents the location of the item along the latent trait scale of cyber dating violence, where the participant has a 50% chance of giving a positive response on the dichotomous scale (Hambleton et al., 1991). Higher scores indicate greater difficulty or severity (i.e., a higher risk for cyber dating violence). To develop two symmetrical scales of aggression and victimisation with the most substantive items, the items were analysed according to their item curve characteristic (ICC) in both scales and their parameter characteristics. The fit of the refined version of the scales was then tested using CFA.

Results

Descriptive analysis

The descriptive analyses are presented in Table 2. For aggression, involvement ranged from 2% (items 4 and 9) to 40.7% (items 6 and 7) for verbal/emotional forms, from 5% (item 12) to 35.5% (item 19) for control and from 0.7% (item 27) to 8.1% (item 20) for sexual violence. General prevalence rates were 56.3% for verbal/emotional violence, 54% for control and 15% for sexual violence.

For victimisation, involvement ranged from 3% (item 9) to 45.7% (item 7) for verbal/emotional forms, from 7.6% (item 12) to 33% (item 19) for control and from 1% (item 26) to 14.3% (item 24) for sexual violence. General prevalence rates were 64% for verbal/emotional violence, 54.8% for control and 29.2% for sexual violence victimisation (Tables 2 and 3).

Given the aims of the present study, items 23, 26 and 27 were eliminated from the aggression and victimisation scales due to their low representativeness in the study sample (less than 3% on both scales, see Table 2). The total number of remaining items was 25.

Table 2. Prevalence rates, discrimination, and severity of the items in cyber dating aggression and victimisation

| Aggression | Victimisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Discrimination (SE) | Severity (SE) | % | Discrimination (SE) | Severity (SE) | |

| Verbal/emotional cyber dating violence | ||||||

| Item 1 | 16.9 | 3.87 (1.68) | 1.05 (0.25) | 27.4 | 2.67 (0.75) | 0.73 (0.26) |

| Item 2 | 5.6 | 3.45 (1.90) | 1.77 (0.59) | 14.9 | 2.71 (0.81) | 1.25 (0.34) |

| Item 3 | 6 | 1.75 (0.83) | 2.21 (0.76) | 14.9 | 2.06 (0.42) | 1.37 (0.23) |

| Item 4 | 2 | 4.91 (4.30) | 2.16 (0.54) | 4 | 3.22 (1.24) | 2.00 (0.38) |

| Item 5 | 8.6 | 1.38 (0.41) | 2.20 (0.44) | 13.2 | 1.44 (0.30) | 1.74 (0.27) |

| Item 6 | 40.7 | 2.19 (0.49) | 0.31 (0.09) | 45 | 1.71 (0.31) | 0.18 (0.20) |

| Item 7 | 40.7 | 2.00 (0.39) | 0.32 (0.09) | 45.7 | 1.97 (0.36) | 0.15 (0.20) |

| Item 8 | 3 | 1.86 (0.57) | 2.63 (0.46) | 8.9 | 2.68 (1.23) | 1.62 (0.16) |

| Item 9 | 2 | 1.20 (0.50) | 3.80 (1.20) | 3 | 2.63 (2.99) | 2.28 (0.70) |

| Total | 56.3 | 64 | ||||

| Control cyber dating violence | ||||||

| Item 10 | 16.6 | 2.74 (0.62) | 1.14 (0.13) | 25.7 | 3.61 (0.69) | 0.73 (0.09) |

| Item 11 | 13 | 2.38 (0.54) | 1.38 (0.16) | 17.9 | 2.35 (0.42) | 1.14 (0.13) |

| Item 12 | 5 | 2.87 (0.73) | 1.93 (0.22) | 7.6 | 2.32 (0.49) | 1.79 (0.20) |

| Item 13 | 21.9 | 2.11 (0.41) | 1.00 (0.12) | 29.7 | 3.17 (0.57) | 0.62 (0.09) |

| Item 14 | 8.6 | 1.82 (0.40) | 1.88 (0.25) | 11.9 | 1.75 (0.33) | 1.66 (0.21) |

| Item 15 | 5.3 | 2.30 (0.55) | 2.04 (0.26) | 10.3 | 3.66 (0.83) | 1.39 (0.13) |

| Item 16 | 7.3 | 3.30 (0.86) | 1.62 (0.17) | 12.3 | 6.65 (2.17) | 1.18 (0.10) |

| Item 17 | 11.7 | 1.24 (0.28) | 2.02 (0.34) | 10.3 | 1.40 (0.29) | 2.01 (0.30) |

| Item 18 | 13.3 | 2.32 (0.49) | 1.36 (0.16) | 16.7 | 3.40 (0.66) | 1.08 (0.10) |

| Item 19 | 35.5 | 1.35 (0.27) | 0.58 (0.13) | 33 | 1.30 (0.23) | 0.71 (0.14) |

| Total | 54 | 54.8 | ||||

| Sexual cyber dating violence | ||||||

| Item 20 | 8.1 | 2.17 (0.86) | 1.79 (0.43) | 13.4 | 2.28 (0.50) | 1.39 (0.17) |

| Item 21 | 2 | 2.11 (0.73) | 2.74 (0.66) | 7 | 2.05 (0.50) | 1.96 (0.26) |

| Item 22 | 3.7 | 2.84 (1.62) | 2.11 (0.37) | 8.3 | 2.37 (0.54) | 1.73 (0.21) |

| Item 23 | 1 | - | - | 1.7 | - | - |

| Item 24 | 5.7 | 4.25 (1.91) | 1.70 (0.28) | 14.3 | 2.99 (0.77) | 1.23 (0.14) |

| Item 25 | 3.7 | 3.17 (1.26) | 2.05 (0.38) | 8.9 | 2.80 (0.72) | 1.62 (0.18) |

| Item 26 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Item 27 | 0.7 | - | - | 2.7 | - | - |

| Item 28 | 2.7 | 2.03 (1.32) | 2.61 (0.58) | 7 | 1.51 (0.40) | 2.27 (0.38) |

| Total | 15 | 29.2 |

Confirmatory factor analysis

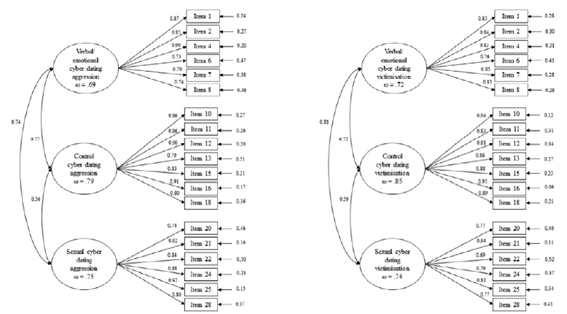

Cyber aggression model. The three-factor model with 25 items was found to have a good fit (χ 2 (272) = 299.81, CFI = .98, RMSEA = 0.02, CI 0.00-0.03). The standardised factor loadings oscillated between .66 (item 17) and .92 (item 25). The correlations of between dimensions were .85 (verbal/emotional-control), .77 (verbal/emotional-sexual), and .59 (control-sexual). The internal consistency of the scales was acceptable; McDonald's ω: .73 (verbal/emotional), .80 (control) and .75 (sexual).

Cyber victimisation model. The three-factor model with 25 items was found to have a good fit (χ 2 (272) = 376.07, CFI = .97, RMSEA = 0.04, CI 0.03-0.04). The standardised factor loadings oscillated between .66 (item 17) and .96 (item 16). The correlations between dimensions were .79 (verbal/emotional-control), .84 (verbal/emotional-sexual), and .64 (control-sexual). The internal consistency of the scales was .78 (verbal/emotional), .85 (control) and .74 (sexual).

Item Response Theory Model

Table 2 presents the discrimination and severity indexes of the items included in the analysis. All items discriminated correctly in their scale, with indexes of over 1, whereas the severity indexes varied between .15 (item 7 victimisation) and 3.80 (item 9, aggression). The ICC analysis (see Figures 1-3) revealed that the probability of answering positively each item was very low in some cases, for example, in relation to items 3 and 5 (less than .1 on the aggression scale). We therefore decided to eliminate those items with a low probability on both scales (aggression and victimisation) and, to maintain symmetry across the two scales, when an item was deleted on one scale, we decided to delete the parallel item from the other scale.

Verbal/emotional cyber dating violence. As shown in Figure 1, items 3 and 9 offered very little information for the latent aggression factor, whereas the results for item 5 reflected a low curve in both factors (aggression and victimisation). These three items had the highest severity indexes and were also those which discriminated least in the aggression factor. The decision was therefore made to eliminate them from both scales. The six remaining items reflected public and private behaviours of diverse difficulty levels, with good discrimination. Items 2 and 8, which reflected public aggression, had the highest severity values, whereas items 6 and 7 were less severe. Item 4 reflected private aggression and presented a high representative value (Table 2).

Control cyber dating violence. The ICC analysis revealed that items 14, 17 and 19 (Figure 2) provided very little information for both latent factors, particularly victimisation, and were also the least discriminatory in both factors. We recommended to eliminate them, leaving the dimension to be represented by seven private items, all with good discrimination indexes and diverse severity levels (Table 2).

Sexual cyber dating violence. The sexual aggression and victimisation items had a high level of discrimination and were also the items with the highest severity indexes of the entire scale (Table 2). No item was eliminated as a result of its ICC (Figure 3), leaving this factor represented by six items that encompassed diverse behaviours, ranging from sending or pressuring to send and share intimate content (items 22 and 24), to spreading private information publicly (item 21) and even using alcohol to obtain sexual favours from one's partner (item 28). These last two items were the ones with the highest severity rates.

Figure 1. Curves of the verbal/emotional cyber dating aggression and victimisation items in accordance with their information (right) and probability (left)

Figure 2. Curves of the control cyber dating aggression and victimisation items in accordance with their information (right) and probability (left)

Figure 3. Curves of the sexual cyber dating aggression and victimisation items in accordance with their information (right) and probability (left)

A CFA was conducted for the 19-item aggression and victimisation scales. The fit of the models was good for both aggression (χ 2 (149) = 163.81, CFI = .99, RMSEA = 0.02, CI 0.00-0.03) and victimisation (χ 2 (149) = 227.71, CFI = .98, RMSEA = 0.04, CI 0.03-0.05). Figure 4 shown the correlation between dimensions, prevalence rates, and the items factor loadings. The correlations between the latent factors were reduced slightly in relation to the initial version, indicating greater discrimination in each of the two factors.

Descriptive analyses of the refined version of the CyDAV-T

Verbal/emotional aggression was the most prevalent dimension (54.3%), followed by control (36.8%) and then sexual aggression (15%). The same trend was found for victimisation: verbal/emotional (63.4%), control (41.9%) and sexual victimisation (29.2%).

Gender analyses revealed that girls exercised more control but were more often victims of sexual violence. Boys had higher rates of sexual aggression. No differences were found for the verbal/emotional aggression scale or for control-related victimisation (Table 3).

Table 3. Prevalence of cyber dating aggression and victimisation in accordance with gender, for the reduced dimensions.

| Boys (N = 143) | Girls (N = 156) | χ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Verbal/emotional cyber dating aggression | 75 | 52.4 | 86 | 55.5 | 0.28 |

| Control cyber dating aggression | 44 | 30.8 | 65 | 41.9 | 4.00* |

| Sexual cyber dating aggression | 31 | 21.8 | 14 | 9.1 | 9.30* |

| Verbal/emotional cyber dating victimisation | 87 | 60.8 | 102 | 65.4 | 0.66 |

| Control cyber dating victimisation | 56 | 39.2 | 69 | 44.2 | .79 |

| Sexual cyber dating victimisation | 28 | 19.7 | 59 | 38.1 | 12.04* |

* p < .05

Evidence of convergent and criterion validity

The means comparison analyses revealed that those involved in all three forms of cyber dating aggression and victimisation had higher means for online moral disengagement and NCS. Significant differences were found in all cases, except that of control aggression and sexual victimisation, for which values were close to statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between Online Moral Disengagement (OMD), Non-Consensual Sharing (NCS) and the reduced dimensions of cyber dating aggression and victimisation.

| Verbal/emotional cyber dating aggression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NI M(SD) | I M(SD) | t(df) | p | |

| OMD | 1.39(0.46) | 1.52(0.44) | -2.35(296) | .019 |

| NCS | 1.09(0.29) | 1.23(0.52) | -2.85(187) | .005 |

| Control cyber dating aggression | ||||

| NI M(SD) | I M(SD) | t (df) | p | |

| OMD | 1.42(0.46) | 1.52(0.42) | -1.86(296) | .064 |

| NCS | 1.11(0.30) | 1.26(0.59) | -2.46(140) | .015 |

| Sexual cyber dating aggression | ||||

| NI M(SD) | I M(SD) | t (df) | p | |

| OMD | 1.42(0.43) | 1.70(0.54) | -3.26(52) | .002 |

| NCS | 1.13(0.31) | 1.41(0.83) | -2.24(45) | .030 |

| Verbal/emotional cyber dating victimisation | ||||

| NI M(SD) | I M(SD) | t (df) | p | |

| OMD | 1.35(0.42) | 1.53(0.46) | -3.42(297) | .001 |

| NCS | 1.07(0.27) | 1.23(0.51) | -3.41(296) | .001 |

| Control cyber dating victimisation | ||||

| NI M(SD) | I M(SD) | t (df) | p | |

| OMD | 1.41(0.45) | 1.54(0.44) | -2.55(297) | .011 |

| NCS | 1.09(0.29) | 1.28(0.58) | -3.35(168) | .001 |

| Sexual cyber dating victimisation | ||||

| NI M(SD) | I M(SD) | t (df) | p | |

| OMD | 1.43(0.44) | 1.54(0.48) | -2.00(296) | .046 |

| NCS | 1.14(0.43) | 1.25(0.48) | -1.93(147) | .055 |

NI = not Involved, I = Involved

Discussion

This study developed and validated a new measure for assessing cyber dating violence among adolescent couples. The study makes an important contribution, because few validated instruments measuring aggression and victimisation are available in Spain for this specific population (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022; Rodríguez-deArriba et al., 2021). The limitations of previous studies were taken into consideration during the development of the instrument. As a result, both sexual cyber dating violence (Kim & Ferraresso, 2022) and behaviours with diverse degrees of severity (Fissel et al., 2022) were included. To this end, we distinguished between the public and private aggressions (Sánchez-Jiménez et al., 2022; Stonard, 2020), as well as the use of multimedia content, since this has been shown to be one of the most severe forms of violence, used as an alternative to face-to-face sexual aggression (Reed et al., 2020). The instrument also highlighted the aggressive nature of the action, to distinguish these behaviours from others that may arise in a playful or consensual intimate context (Brown & Hegarty, 2018). Moreover, young people's opinions were considered when developing the updated instrument, to avoiding including behaviours considered obsolete.

The CyDAV-T comprises three of the most relevant dimensions in the study of cyber dating violence: verbal/emotional, control and sexual violence (Reed et al., 2017), finding good fit indexes for both aggression and victimisation scales. To date, few validated instruments containing a sexual dimension have been available (Fissel et al., 2022; Watkins et al., 2018), and none of these focus on the adolescent population. Moreover, the dimensions of the CyDAV-T reported evidence of convergent validity, since they were related to other forms of interpersonal aggression, such as NCS, and criterion validity, since higher scores were recorded also for online moral disengagement.

The analyses based on IRT determined the contribution of each item to its latent factor and revealed that each scale contained items of different severity levels, with public behaviours being the ones with the highest indexes. Nevertheless, these analyses also revealed that not all public behaviours represented their latent factor to the same degree, with some having low discrimination and probability indexes. This was particularly notable in the case of control victimisation, where repeatedly contacting one's partner's friends or family members to determine their whereabouts (item 14) provided less information about its latent factor. As a result, the refined control cyber aggression and victimisation scales were made up of private items of differing degrees of severity, which indicates that this form of cyber violence is relevant only in the private sphere, since it is precisely the online context that enables someone to control and monitor their partner without their knowledge (Utz & Beukeboom, 2011). Much the same occurs with the sexual forms: private items were more discriminating than public ones, which were represented only in the spreading of rumours about one's partner's sexual behaviour (item 22). This finding is consistent with that reported by Fissel et al. (2022) . In their study on cyber victimisation among adults, only one public item represented the victimisation scale, since the frequency of public sexual violence among the community population was very low. The very low rates of public sexual violence in the present study prevented any analysis of their contribution to the factors analysed. However, this result should be taken with caution, since the size of the sample was small. Future studies should strive to recruit more representative samples to confirm this finding.

The analysis of the items' ICCs revealed that although some of them were not particularly discriminating of their latent factor, this low representativeness differed in relation to victimisation and aggression (for example, item 9). Nevertheless, we opted to eliminate all items with a low ICC in both factors (aggression and victimisation), following the principle of symmetry (i.e., maintaining the same items in both factors to reduce bias in the interpretation of the results). Although recent studies have reported non-symmetrical aggression and victimisation scales (Redondo et al., 2022), in this study, we opted for a more conservative approach because of the specificity of the sample. The refined scale comprised 19 equivalent items for aggression and victimisation, with an acceptable fit. The prevalence rates with this refined model were similar to those returned by the 25-item version, except in the case of control, where rates dropped when less discriminating items (particularly item 19, which had the highest prevalence rate) were eliminated. Consequently, although the 25-item scale had acceptable fit indexes, the refined version contained more informative items. In any case, given the differential pattern of some items in the aggression and victimisation scales, further research is required to confirm these results.

In terms of prevalence data, verbal/emotional forms of violence were the most common, followed by control. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Smith-Darden et al., 2017), although not with that reported by others (Cava & Buelga, 2018). Conclusive results were found, however, in relation to both sexual violence, which was the least frequent of the three forms analysed (Reed et al., 2017; Watkins et al., 2018), and gender differences in control and sexual forms (Cava et al., 2020; Kernsmith et al., 2018; Reed et al., 2017).

The present study has several limitations. The study sample was small, and the sampling method was based on accessibility, a circumstance that reduces representativeness and limits the generalisation of the results. Having a larger sample would have enabled us to divide the sample into two sub-groups and to perform prior Exploratory Factor Analyses. Although some authors argue that this procedure is not necessary when the study is based on a previous theoretical model (Byrne, 2013), it would have lent the three-factor solution greater statistical validity. Furthermore, a larger sample would have enabled us to analyse gender invariance, a key issue in the study of adolescent dating violence.

In relation to the focus groups, the use of a young adult sample may have resulted in the limited extrapolation of personal experiences to the adolescent population, which in turn may have affected the final selection of the 28 items. Although we decided to contact first-year university undergraduates due to their being closest in age to the adolescent population participating in the study, it is true that the upper limit of the age range of those taking part in the focus groups was 23 years. Future studies may wish to corroborate these results with adolescent focus groups.

Another limitation is linked to the decision to dichotomize the variables, which resulted in the loss of information about the frequency of participants' involvement. However, this is the recommended procedure for IRT analysis in constructs with non-normality items distribution (Fissel et al., 2022; Menesini et al., 2011). Finally, the time interval chosen (one year) may seem excessive given the nature of adolescent dating relationships, but it is one of the most used in the literature (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022). Future studies may analyse this aspect by reducing the interval and comparing the resulting prevalence rates.

Despite these limitations, the CyDAV-T, in both its global and refined versions, is proposed as a valid instrument for assessing cyber violence among adolescent dating couples. The use of robust statistical analyses, such as CFAs and IRT, enabled us not only to validate the instrument's factor structure, but also to identify the most representative items for each scale, with differing levels of severity