Suicidal behavior is a serious public health problem; each year about 700,000 people commit suicide around the world (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). In Spain, suicidal behavior is the leading cause of death in young people between the ages of 15 and 19 (National Institute of Statistics, 2021), with an increase of almost 50% for individuals between the ages of 10 and 14 in 2021 compared to 2020. It is a complex, multidimensional, and multicausal phenomenon (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2022; Geoffroy et al., 2022; Herruzo et al., 2023), with a variety of manifestations that include ideation and planning, suicidal communication, attempts and completed suicide (Eslava et al., 2023).

In the meta-analysis by Lim et al. (2019), 14.2% of adolescents were found to have had suicidal ideation in the last 12 months. In Spain, the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation in adolescents is approximately 30% (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2020). Many adolescents experience suicidal ideation at some point in their lives, varying in severity from passive suicidal thoughts (i.e., I do not want to live), to active suicidal thoughts (i.e., I plan to kill myself) or even suicide planning (date, place, method) (Buelga et al., 2023; Geoffroy et al., 2022). Suicidal behavior can be understood as a continuum that encompasses different manifestations with ascending severity that range from ideation and planning to suicidal communication, suicide attempts and completed suicide (Al-Halabí & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2021; Fonseca- Pedrero et al., 2020; Moreno-Mansilla et al., 2022). This process is not linear or gradual, protective factors of turning back may appear, as well as risk factors that increase the severity and magnitude of the risk of suicidal behavior (Geoffroy et al., 2022; Ruch et al., 2023). Relational conflicts in adolescence have been identified as a triggering factor for the acute onset of suicide attempts (Villar-Cabeza et al., 2017).

From this perspective, peer victimization and cyber-victimization have been recognized as important predictive risk factors for suicidal behavior in adolescents (Koyanagi et al., 2019; Lucas-Molina et al., 2018; Chamizo-Nieto & Rey, 2023). Peer victimization includes any act of aggression carried out by a child or adolescent toward another of a similar age (Cava et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2015). This victimization can manifest itself directly through physical and verbal aggression, and indirectly through more subtle forms such as spreading secrets or rumors, exclusion from groups and activities, and blackmail or threats of ending the friendship (Cava et al., 2021).

Since the emergence and widespread access at ever younger ages to Relation, Information and Communication Technologies (RICTs), peer victimization (from now on, traditional victimization) continues regularly on the Internet through cyberbullying. Cyberbullying refers to the use of electronic devices by one or more people to intentionally attack someone who cannot defend themselves (Cosma et al., 2020; Kowalski et al., 2014). Previous studies (Buelga et al., 2010, 2022; González-Cabrera & Machimbarrena, 2023; Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2021) suggest that cyberbullying has specific characteristics (anonymity, public breadth, 24/7 permanence, virality), which increase the damage caused to the victim (Estévez et al., 2023; Lanzillo et al., 2023; Lucas-Molina et al., 2022). Cyber-victimization can occur through direct attacks on the person, such as threats or insults, and also through indirect attacks, such as identity theft or photo manipulation (Buelga et al., 2019; Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2021).

Numerous meta-analysis studies (Farrington et al., 2023; Kwanya et al., 2022), systematic reviews (Buelga et al., 2022; John et al., 2018) and longitudinal studies (Holfeld & Mishna, 2019) demonstrate the co-occurrence of traditional victimization and cyber-victimization. In 2014, Kowalski et al. observed that 80% of victims of traditional victimization were also subsequently victimized in the virtual environment. However, recent studies (Li et al., 2022) highlight the enormous predominance that the virtual environment currently has in the lives of adolescents, and how victimization is increasingly starting in virtual environments. Li et al. (2022) found in their study that 63% of cyberbullying victims later suffered traditional victimization, while the percentage dropped to 30.5% for those who suffered traditional victimization and were later cybervictimized.

Another crucial point of interest in scientific research is the negative impact that traditional victimization and cyber-victimization cause, separately and jointly, on the victim's suicidal behavior. Several longitudinal studies focusing on traditional victimization have confirmed a strong relationship between this type of victimization and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence (Geoffroy et al., 2018; Holt et al., 2015; Sorrentino et al., 2023) and adulthood (Geoffroy et al., 2022; Takizawa et al., 2014). In the longitudinal study by Perret et al. (2020), cyber-victimization was observed to be a more immediate risk factor for suicidal ideation than traditional victimization. In cross-sectional studies, 50% of cyber-victims report suicidal ideations (Alhajji et al., 2019; Nagamitsu et al., 2020), and almost 20% of these have attempted suicide (Nagamitsu et al., 2020). The risk of suicidal behavior is higher in cyber-victimization compared to traditional victimization (Heerde & Hemphill, 2019; Li et al., 2022), and it increases considerably when the victim suffers both traditional victimization and cyber-victimization (Buelga et al., 2022; Farrington et al., 2023; Li et al., 2022). In terms of gender differences in the relationship between suicide and both traditional victimization and cyber-victimization, girls are at a higher risk of suicidal ideation (Abrahamyan et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2019; Rodelli et al., 2018) and suicide attempts (Kuehn et al., 2019). Regarding age, the results are more controversial (Quintana-Orts et al., 2022), and the studies seem to point to a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation between the ages of 12 and 14 (Rodelli et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2015) and attempted suicide between the ages of 15 and 17 (Geoffroy et al., 2018; Perret et al., 2020).

The family, and especially family communication, plays a central role in the psychosocial adjustment and healthy development of children (Buelga et al., 2017; Cava et al., 2014; Centelles et al., 2021; Houbrechts et al., 2023; Navarro et al., 2022; Millan Ghisleri & Caro Samada, 2022). Absence of or poor family communication has been associated with a decrease in personal and social resources in children, and with it, an increased risk of suicidal behavior (Lensch et al., 2021; Perquier et al., 2021; Wang, 2023), and traditional victimization and cyber-victimization (Buelga et al., 2016; Cañas et al., 2020; Wang & Jiang, 2022). In addition, when there is no open and positive communication with parents, poly(victimization) is prolonged over time (Gámez-Guadix, 2017; Garaigordobil & Navarro, 2022), and with it, the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Buelga et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2023).

Studies show that victims of peer violence and cyberbullying who communicate with their parents report lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Buelga et al., 2019; Cava, 2011; López-Castro & Priegue, 2019; Romero-Abrio et al., 2019), and suicidal behavior (Helfrich et al., 2020; Pereira et al. 2022). Only if children share with their parents what is happening to them and express the suffering they are experiencing, can parents offer them maximum protection and emotional support (Buelga et al., 2017; Cava et al., 2014; Navarro et al., 2021; Salton et al., 2023; Sun & Ban, 2022).

As noted by Farrington et al. (2023), the issue is that there is still little research on protective family factors associated with traditional victimization and cyber-victimization, compared to the larger existing literature on family risk factors. In fact, we believe that, except for the works of Helfrich et al. (2020) and Pereira et al. (2022), there is no scientific study that has analyzed the protective role of family communication in the specific problem of suicidal ideation in adolescent victims of traditional victimization and cyber-victimization, considering these four variables together.

The main purpose of this study was to analyze, through two different moderated mediation models, the possible moderating role of family communication in the relationships between traditional victimization, cyber-victimization, and suicidal ideation. Research was also directed primarily at discovering the direct predictive capacity of traditional victimization and cyber-victimization, as well as their mediating role, in the prediction of suicidal ideation in adolescents.

Specifically, the following objectives were set: (1) to analyze the direct effects of both traditional victimization and cyber-victimization on suicidal ideation; (2) to analyze the indirect effects - mediating role - of cyber-victimization in the relationship between traditional victimization and suicidal ideation; (3) to analyze the indirect effects -mediating role- of traditional victimization in the relationship between cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation; (4) to explore the moderating role of family communication in both mediation models. In addition, sex and age were introduced as covariates to control the possible effect of these on the study variables.

The proposed models hypothesized a positive direct effect of traditional victimization on suicidal ideation (model 1), and of cyber-victimization on suicidal ideation (model 2), and a positive indirect effect through traditional victimization (model 1) and cyber-victimization (model 2). Family communication was also hypothesized to moderate the effects of traditional victimization and cyber-victimization on suicidal ideation in both models, as well as the relationship between both forms of victimization, given that family communication is hypothesized as a buffering factor of the negative experiences suffered by the children, helping them cope with these negative experiences.

Method

Participants

A sample stratified by conglomerates was used to select the participants. The sampling units were the public and state-funded private educational centers of Valencia (Spain). The sample size -with a sampling error of ±3%, confidence level of 95% and p = q = .5 (N = 218,317), was estimated at 995 students. A total of 1007 adolescents participated in the study, 523 boys (51.9%) and 484 girls (48.1%), aged from 12 to 18 years (M = 14.73, SD = 1.75). The participants were studying Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO) and Baccalaureate (pre-university grade) in four educational centers (three public centers and one state-funded private center).

Instruments

Peer Victimization Scale (Cava et al., 2007). Consists of 20 items that evaluate how often during the last year the adolescent has been victimized at school by his/her peers with a response range from 1 (never) to 4 (many times). The scale includes three factors: physical victimization (4 items), verbal victimization (6 items), and relational victimization (10 items). Physical victimization describes situations such as being hit or pushed (e.g., A classmate has hit me); verbal victimization refers to situations such as being teased or insulted (e.g., A classmate has made fun of me), and relational victimization describes situations such as being the victim of malicious rumors and social exclusion (e.g., A classmate has told others not to associate with me). In this sample, the reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α of these factors was .63 for physical victimization, .85 for verbal victimization, .90 for relational victimization, and .93 for the total scale.

Cyber-victimization Scale (Buelga et al., 2019). Composed of 18 items that evaluate how often during the last year the adolescent has been victimized in the virtual environment by his/her peers with a response range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The scale consists of two factors that measure direct cyber-victimization (10 items) and indirect cyber-victimization (8 items). Direct cyber-victimization includes verbal aggressions (e.g., I have been insulted or ridiculed on social networks) and social aggressions (e.g., I have been ignored on social networks). Indirect cyber-victimization includes attacks in which the victim is harmed without direct confrontation (e.g., They have created a false profile on the Internet with my personal data). In this sample, the reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α) was .84 for the direct cyber-victimization subscale, .77 for indirect cyber-victimization, and .89 for the total scale.

Suicidal Ideation Scale (Mariño et al., 1993; adaptation by Sánchez-Sosa et al., 2010). Consists of 4 items that measure intrusive and repetitive thoughts about self-inflicted death (e.g., I thought about killing myself). The person must indicate with options from 0 to 4 (« 0 days », « 1-2 days », « 3-4 days », « 5-7 days »), the number of days during the last week that they have had suicidal thoughts or wishes. In this sample, the reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α) was .75.

Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes & Olson, 1982; adaptation by Estévez et al., 2005). This scale includes a dimension of open communication with parents, made up of 11 items that evaluate the adolescent's perception of open communication with their parents through a range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). These items assess the existence of positive and fluid communication patterns between the child and their parents (e.g., I can talk to them about what I think without feeling bad or uncomfortable). In this sample, the reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α) was .83.

Procedure

An informative seminar for teachers and management was held with the participating schools to explain the purpose of the project. After obtaining parental authorization for their children's participation in the study, previously trained researchers administered the instruments during tutoring hours. The instruments were completed in paper and pencil format, and the administration process was systematized (a similar presentation of the study was carried out in all classrooms and the scales were always presented in the same order). The participants were informed that their participation in the research was voluntary and anonymous. The privacy of their answers was guaranteed to avoid possible effects of social desirability. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (Protocol Number: H1456762885511).

Data Analysis

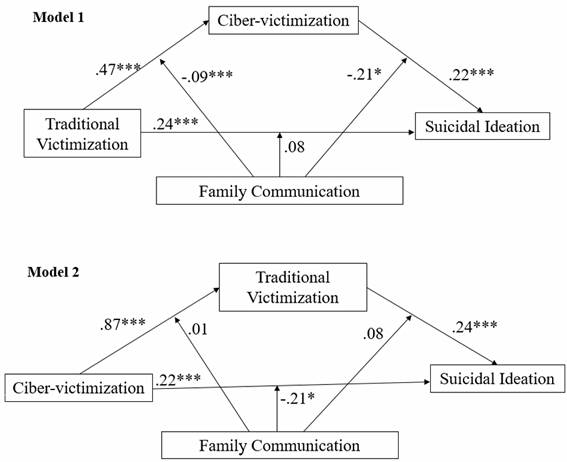

First, reliability coefficients, descriptive statistics, and bivariate correlations (Pearson) were calculated between the traditional victimization, cyber-victimization, family communication, suicidal ideation, sex, and age variables. Subsequently, to examine the relationships between traditional victimization, cyber-victimization, and suicidal ideation, as well as the possible moderating role of family communication in these relationships, two moderated mediation models were estimated (see Figure 1). Prior to their estimation, the necessary assumptions to carry out this type of analysis were checked (non-collinearity, independence of the residuals, homoscedasticity, and normal distribution of the residuals). In model 1, traditional victimization was hypothesized as a predictor variable, cyber-victimization as a mediator, and suicidal ideation as an outcome, exploring the possible moderating effect of family communication in all these relationships. In model 2, cyber-victimization was hypothesized as a predictor variable, traditional victimization as a mediator, and suicidal ideation as an outcome, analyzing the possible moderating effect of family communication in these relationships. These two moderated mediation models were estimated using model 59 of the macro-PROCESS for SPSS (Hayes, 2018). Given that previously significant correlations of sex and age were observed with some of the variables analyzed in these models, both sex and age were included as covariates. The standard errors of the indirect effects were estimated with the bootstrapping method based on 5000 samples, being considered significant when 95% of the confidence interval does not contain zero. All analyses were performed with SPSS-28.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and the correlations between all the study variables.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | 0.48 | 0.50 | - | ||||

| 2. Age | 14.63 | 1.75 | -.01 | - | |||

| 3. Traditional victimization | 1.44 | .39 | -.01 | -.06 | - | ||

| 4. Cyber-victimization | 2.41 | .58 | .09* | .01 | 66** | - | |

| 5. Family communication | 3.65 | .55 | .02 | -.08* | -.26** | -.22** | - |

| 6. Suicidal ideation | 1.31 | .45 | .07* | .06 | .35** | .35** | -.27** |

Note:Sex was coded as a dummy variable: 0 = boy, 1 = girl

**p < .01;

*p < .05; small effect size: .10 < rxy < .30, medium: .30 < rxy < .50, large rxy > .50 (Cohen, 1988).

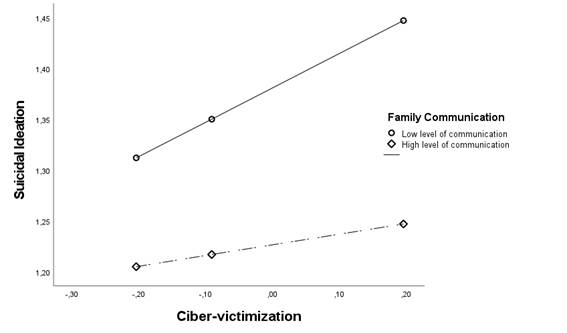

The results of the estimation of the hypothesized moderated mediation models can be seen in Table 2 and Figure 1. Both model 1 and model 2 explain 19% of the variance in the suicidal ideation variable. Model 1 shows significant direct effects of traditional victimization on suicidal ideation (B =.24, SE =.05; 95% CI: 0.147, 0.326). This victimization is also a significant predictor of cyber-victimization (B = 47, SE = .02; 95% CI: 0.435, 0.507), which significantly predict suicidal ideation (B =.22, SE = .06; 95% CI: 0.099, 0.346). The indirect effect of traditional victimization on suicidal ideation through cyber-victimization is significant (B = .15, SE = .05; 95% CI: 0.045, 0.253). In addition, family communication is a significant moderating variable of the relationship between traditional victimization and cyber-victimization (B = -.09, p< .001). This moderator effect is shown graphically in Figure 2. This figure shows that, although there is a positive relationship between traditional victimization and cyber-victimization in both low and high levels of family communication (B = .52, SE = .02; 95% CI: 0.481, 0.560: low level of communication; B =.42, SE = .03; 95% CI: 0.371, 0.471: high level of communication), the slope indicating the relationship between both variables is more pronounced for low levels of family communication. This result indicates a stronger relationship between traditional victimization and cyber-victimization in those adolescents with low levels of family communication. In addition, family communication is also a significant moderating variable of the relationship between cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation (B = -.21, p < .05). Cyber-victimization is positively related to suicidal ideation in those adolescents who have low levels of family communication (B = .34, SE = .07; 95% CI: 0.204, 0.473). However, this relationship is not significant in adolescents with high levels of family communication (B =.10, SE =.09; 95% CI: -0.073, 0.285), given that zero is included between the confidence intervals. This moderating effect is presented graphically in Figure 3. Finally, no moderating effect of family communication is observed in the relationship between traditional victimization and suicidal ideation (B = .08, SE =.07; 95 % CI: - 0.060, 0.220). Traditional victimization has a similar positive direct effect on adolescent suicidal ideation, with both high and low levels of family communication.

Table 2. Mediation Models with Family Communication as a Moderating Variable.

| Model 1 | Cyber-victimization | Suicidal ideation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | t | Β | t | |

| Predictors Traditional victimization | .47 | 25.56*** | .24 | 5.18*** |

| Family communication | -.03 | -2.01* | -.14 | -5.75*** |

| Traditional victim. x family communication | -.09 | -3.67*** | .08 | 1.12 |

| Cyber-victimization | .22 | 3.54*** | ||

| Cyber-victimization x family communication | -.21 | -2.29* | ||

| Control variables Sex | .06 | 4.29*** | .05 | 1.89 |

| Age | .01 | 1.90 | .01 | 2.08* |

| F | 172.94*** | 33.11*** | ||

| Model 2 | Traditional victimization | Suicidal ideation | ||

| Β | t | Β | t | |

| Predictors Cyber-victimization | .87 | 25.48*** | .22 | 3.54*** |

| Family communication | -. 08 | -4.85*** | -. 14 | -5.75*** |

| Cyber-victimization x family communication | . 01 | 0.28 | -.21 | -2.29* |

| Traditional victimization | .24 | 5.18*** | ||

| Traditional victim. x family communication | .08 | 1.21 | ||

| Control variables Sex | -.05 | -2.73** | .05 | 1.89 |

| Age | -. 02 | -3.33** | .01 | 2.08* |

| F | 172.82*** | 33.11*** | ||

Note:Sex was coded as a dummy variable: 0 = boy, 1 = girl

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

Figure 2. Associations Between Traditional Victimization and Cyber-Victimization Depending on the Level of Family Communication.

Figure 3. Associations Between Cyber-victimization and Suicidal Ideation Depending on the Level of Family Communication.

For model 2 (see Table 2 and Figure 1), significant direct effects of cyber-victimization on suicidal ideation were found (B =.22, SE = .06; 95% CI: 0.099, 0.346). Cyber-victimization also significantly predicts traditional victimization (B =.87, SE = .03; 95% CI: 0.802, 0.936), and this victimization in turn predict suicidal ideation (B = .24, SE = .05; 95% CI: 0.147, 0.326). The indirect effect of traditional victimization on suicidal ideation through cyber-victimization is significant (B = .16, SE =.04; 95% CI: 0.086, 0.226). It can also be seen that family communication significantly moderates the relationship between cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation (B = -.21, p < .05). This moderation was also confirmed in model 1, and this moderating effect is shown graphically in Figure 3. This moderating effect implies that the positive relationships between cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation are found only in adolescents with low levels of family communication (B = .34, SE = .07, 95% CI: 0.204, 0.473). The relationship between cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation was not significant for adolescents with high levels of family communication (B =.10, SE =.09; 95% CI: -0.073, 0.285). It was also observed that family communication was not a moderating variable of the direct effect of traditional victimization on suicidal ideation (B =.08, SE =.07; 95% CI: -0.060, 0.220), as in model 1. Lastly, family communication was found to not be a moderating variable of the direct positive effect of cyber-victimization on traditional victimization (B = .01, SE = .04; 95% CI: -0.072, 0.096), which implies that cyber-victimization allows predicting traditional victimization for both adolescents with high and low levels of family communication.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the direct and indirect effects (mediators) of traditional victimization and cyber-victimization on suicidal ideation in adolescents with two different moderated mediation models, as well as the possible moderating role of family communication in the relationships between traditional victimization, cyber-victimization, and suicidal ideation.

The results of our study confirm, first, the existence of positive direct effects of traditional victimization (model 1) and cyber-victimization (model 2) on suicidal ideation. These findings are in line with previous literature that has shown that traditional victimization (Benatov et al., 2022; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2022; Kim & Ko, 2021) and cyber-victimization (Buelga et al., 2022; Iranzo et al., 2019; Varela et al., 2022) separately cause enormous psychological distress associated with an increase in suicidal ideation. The Save the Children report (2021) reveals that 35% of minors between the ages of 10 and 19 victimized in the school context by their peers have had suicidal thoughts. An impact that is even greater for cyber-victimization, with 50% of cyber-victims having suicidal ideations (Alhajji et al., 2019; Nagamitsu et al., 2020), and of these, 35% go on to plan their death (Alhajji et al., 2019) and 20% try (Nagamitsu et al., 2020). The magnitude of the risk of suicidal ideation is double (Hinduja & Patchin, 2019) and even triple (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020) when the adolescent is subjected to both offline and online victimization.

Second, the indirect effects analyzed have also been confirmed. Specifically, the results obtained allow us to confirm both the mediating role of cyber-victimization in the relationship between traditional victimization and suicidal ideation, and the mediating role of traditional victimization in the association between cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation. These indirect effects demonstrate the existence of close relationships between traditional victimization and cyber-victimization, in line with the idea of co-occurrence (González-Cabrera & Machimbarrena, 2023; Villora et al., 2020). We have observed that the predictive capacity of cyber-victimization over traditional victimization is greater than that found inversely, and this effect is also highly significant.

This result highlights the central role that online reality currently has in the lives of adolescents (Cava et al., 2023; Estévez et al., 2023; Mantey et al., 2023; Mula-Falcón & González, 2023; Ortega-Barón et al., 2021, 2022; Walsh et al, 2024). A total of 80% of children between the ages of 9 and 16 connect to the Internet every day, with an average daily connection time of almost 4 hours among adolescents between the ages of 15 and 16 (Smahel et al., 2020). Perhaps the Internet is now a huge social laboratory for experimentation and social participation in which, if the adolescent verifies that there is online social validation regarding cyber-victimization of a victim, the latter becomes more easily a target of harassment in the real environment.

Regarding the moderating role of family communication, the results obtained are very interesting and constitute a novel contribution of this study to suicidal ideation in adolescent victims of cyberbullying and traditional violence. First, our results indicate that family communication is moderating the direct effect of traditional victimization on cyber-victimization. This moderation suggests that when there are general patterns of open communication in the family, the direct effect of traditional victimization on cyber-victimization decreases, this being crucial to reduce the risk of suicidal ideation increased by its co-occurrence. The moderating capacity of family communication in these relationships can possibly be explained by the fact that online victimization often occurs when the child is in the family home (Buelga et al., 2016; Helfrich et al., 2020). In addition, this cyber-victimization occurs through electronic devices commonly purchased by parents. This facilitates family intervention, which highlights the importance of family communication in preventing and reducing cyber-victimization (Navarro et al., 2021; Salton et al., 2023; Sun & Ban, 2022; Romero-Abrio et al., 2019; Yubero et al., 2018). The reality is that children usually lack the necessary resources to handle cyber-victimization situations that cause them intense suffering on their own (González‐Cabrera et al., 2023; Helfrich et al., 2020). They need the adult to take the necessary actions to remove, for example, offensive content about their child on the web (e.g., a forum created to harass them or a fake profile for impersonation). In short, our encouraging results show that when there is open communication in the family, cyberbullying in children who suffer traditional victimization is reduced.

Moreover, family communication also moderates the suicidal ideation in cybervictimized adolescents. Positive, open, and fluid communication, where the exchange of views between parents and children is carried out in a clear, respectful, and empathetic way, not only reduces cyber-victimization in adolescents who suffer traditional victimization, but also buffers the effect of cyber-victimization on suicidal ideation. The results corroborate our hypothesis, and coincide with the scarce existing literature on the joint associations of these three variables (Helfrich et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2022). Previous studies have focused extensively on separately analyzing the relationships of family communication with suicidal behavior (Lensch et al., 2021; Perquier et al., 2021; Wang, 2023) and with cyberbullying (Cañas et al., 2020; Wang & Jiang, 2022). In addition, other protective family factors have been investigated in suicidal ideation, such as family functioning (Sánchez-Sosa et al., 2010), family acceptance (Nguyen et al., 2020) and the co-use strategy in parental mediation (Navarro et al., 2013). If we take into account the magnitude of the current problem of suicidal behavior in the child and adolescent population, the development of programs that include these family protection factors, and especially open family communication, undoubtedly become highly effective prevention strategies.

In our study, another interesting result is that contrary to the results obtained with cyber-victimization, family communication does not have a similar moderating role for traditional victimization. Possibly, this finding is explained because traditional victimization occurs in the school context, where teachers and classmates play a determining role (Lucas-Molina et al., 2022). The studies conducted by Košir et al. (2020, 2023), Sánchez-Sosa et al. (2010) and Thornberg et al. (2022) corroborate this idea, suggesting that supportive relationships with peers and teachers are protective factors against traditional victimization.

Family communication did not buffer the effect of traditional victimization on suicidal ideation either. This result can also be explained by the greater role that teachers and classmates have in stopping situations of peer victimization in the educational context (Galindo-Domínguez & Losada, 2022; Košir et al., 2023; Ortega-Barón, et al, 2016). And from there, reduce the psychological distress caused by victimization (Li et al., 2022; Perret et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2023). A distress that is directly linked to an increase in suicidal ideation (Benatov et al., 2022; Iranzo et al., 2019). As recommended by Iorga et al. (2023), educational policies for the prevention of cyber-victimization and promotion of emotional well-being in students need, as a priority, to develop programs that train teachers with extensive knowledge and effective skills to manage and eradicate this behavior.

This study has some limitations. First, its cross-sectional and correlational nature does not allow establishing causal relationships between the variables analyzed. A longitudinal study could clarify the relationships established between the different variables of this study. Thus, it would be of interest, as in the study by Perret al. (2020), to verify longitudinally whether the effects of cyber-victimization on suicidal ideation are more immediate than those observed with traditional victimization, which seem to be sustained over time (Geoffroy et al., 2022; Moore et al., 2017). Other variables of the suicidal behavior continuum, such as attempted suicide, could also be included in future research. Likewise, it would be interesting to carry out a study on the moderating role of the school variables of teacher help and affiliation with classmates in the relationships analyzed in our work. In addition, it would be interesting to use qualitative techniques to understand, from the cyber-victims' perspective, the role played by these school factors, as well as family communication, in the experiences of cyberbullying and suicidal ideation.

Despite these limitations, this study provides novel data that raises several issues with important practical implications. First, it highlights the priority to establish effective action plans to prevent suicide and peer cyber-victimization in the adolescent population. From this perspective, the WHO (2021) in its application guide for suicide prevention, recommends a positive approach to mental health, to enhance the socio-emotional skills of life in adolescents. In this line, transdiagnostic psychological interventions carried out in the educational context are of particular interest to prevent emotional problems in students and improve their socio-emotional adjustment (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2023).

Among the proposed actions, in line with our results, the WHO (2021) suggests promoting a safe environment at school with programs against bullying and cyberbullying, generating healthy social support on the Internet, increasing the knowledge of educational staff about suicide, thus improving its detection and action in the school environment, and also increasing parents' knowledge about the mental health and psychosocial well-being of their children.

Our work also reveals the central role of family in the lives of adolescents, and especially, family communication in situations of cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation in their children. Family communication continues to be, as Olson highlighted in the eighties of the last century, the facilitating dimension on which the emotional bond between parents and children is built and the way to face and solve the problems and conflicts of daily life. Family communication proves to be a significant protective factor to reduce the cyber-victimization and suicidal ideation of children, and it is essential, as recommended by the WHO (2021), to include the family in suicide prevention programs. In short, in all those programs that contribute to promoting the mental health and positive development of those children and adolescents who have never experienced life before the Internet, and who are called Generation Z (born in the late nineties and early 2000s), and currently, Generation Alpha (born after 2010).