Introduction

One in every two children or young people are victims of violence and/or maltreatment each year, which poses critical social, economic, and health costs (World Health Organization [WHO, 2020]). Child maltreatment involves acts (i.e., abuse) and/or omissions (i.e., neglect) which cause or has the potential to cause harm to children (McCoy & Keen, 2013). Different subtypes of child maltreatment have been described in the literature, namely a) physical abuse (i.e., non-accidental physically punitive actions, such as hitting or kicking); b) emotional/psychological abuse (i.e., threatening, insulting, or humiliating the child); c) sexual abuse (i.e., sexual contact (or attempt) aimed at the sexual gratification of another person (adult or other child) and where true consent must be absent); d) physical neglect (i.e., lack of provision basic care such as hygiene or food and lack of supervision); and e) emotional neglect (i.e., emotional deprivation, absence of a secure and responsive environment, absence of responsiveness to emotional needs) (Barnett et al., 1993; Mathews & Collin-Vezina, 2019; Starr et al., 1990).

In face of severe maltreatment and family's inability to protect the child, some of the young people who are victims of maltreatment are placed in out-of-home care services. Out-of-home care is a protective arrangement to children and young people who are unable to live with their families, protecting them from further harm and promoting their rights. Out-of-home care includes family foster care (i.e., kinship or non-kinship foster parents) and residential care (i.e., group homes, treatment group settings). According to a recent report from Eurochild & UNICEF (2021), around 758,018 children are placed in out-of-home care in the European Union countries, most of them in family foster care (around 60%). Evidence suggests that most of these children have suffered some type of neglect, e.g., physical neglect (51%-98%), emotional or psychological neglect (around 60%) (Collin-Vezina et al, 2011; Del Valle et al., 2003; Raviv et al., 2010), or lack of supervision (77%-85%; Petrenko et al., 2012; Raviv et al., 2010). Experiencing different types of abuse is also highly reported, such as emotional abuse (around 70%; Collin-Vezina et al., 2011; Raviv et al., 2010), physical abuse (40%-60%; Collin-Vezina et al., 2011; Del Valle et al., 2003), and psychological abuse (around 30%-40%; Del Valle et al., 2003; Morantz et al., 2013). Sexual abuse emerges less frequently, ranging between 2% and 38% (e.g., Collin-Vezina et al, 2011; Del Valle et al., 2003; Khoo et al., 2012; Morantz et al., 2013; Petrenko et al., 2012; Raviv et al., 2010).

Child Maltreatment and Mental Health of Young People in Out-of-home Care Services

Child maltreatment increases the risk of mental health problems during childhood and adolescence (Leeb et al., 2011; Vilariño et al., 2022). Mental health problems may be operationalized into internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Internalizing symptoms comprises problems related to internal difficulties such as anxiety, depression, isolation, or somatic complaints. Externalizing symptoms mainly comprises conflicts with others, such as delinquent and aggressive behaviors (Achenbach, 1991). Research suggests that while some youth in out-of-home care show resilient outcomes in the face of previous adverse experiences (Isakov & Hrncic, 2021; Lou et al., 2018), other youth show significant mental health problems (Pecora et al., 2009). These mental health problems are greatly overrepresented among young people in the child protection system and particularly in out-of-home care (Egelund & Lausten, 2009). Not only do these young people have to deal with a series of separations, including placement changes and instability in care (Pecora et al., 2009), they must also deal with the developmental challenges that all young people face (Jansen, 2010). Although the role of maltreatment prior to placement into care has been widely studied, results appear scattered and inconsistent, requiring additional efforts to systematize this evidence.

Evidence indicates that emotional abuse and emotional and physical neglect are significantly associated with anxiety, depression, anger, post-traumatic stress, and dissociation, and that sexual abuse was also related to all these outcomes, except depression (Collin-Vezina et al., 2011). Specifically, emotional abuse and neglect have stronger associations with anxiety, depression, and anger than other forms of maltreatment such as physical neglect, sexual abuse or physical abuse (van Vugt et al., 2014). In the same study, emotional neglect positively predicted anger problems in emerging female adults in care, and surprisingly physical neglect revealed the opposite result. Physical neglect was also positively associated with later dissociation difficulties (van Vugt et al., 2014).

Furthermore, physical abuse has not only been significantly associated with depression, anger, post-traumatic stress, and dissociation (Collin-Vezina et al, 2011), but with externalizing symptoms too (Petrenko et al., 2012; Raviv et al., 2010). Petrenko et al. (2012) found that physical abuse was the stronger predictor of externalizing symptoms, and that physical neglect was significantly associated with internalizing symptoms, as reported by caregivers. In addition, other authors have found that if physical abuse was positively associated with externalizing symptoms, and sexual abuse with dissociation and sexual concerns, non-significant associations were found on failure to provide, emotional abuse, and moral/legal abuse (Raviv et al., 2010). Unexpectedly, negative and significant associations were found between lack of supervision and educational neglect and externalizing symptoms (Raviv et al., 2010).

These findings were found with samples of children, adolescents, and late adolescents, suggesting that abuse and neglect might affect adolescents' mental health differently and that the same type (e.g., physical neglect) may have different associations with mental health outcomes. In addition, differences can also be found according to the informant (e.g., caregivers and young people) (Petrenko et al., 2012). As such, it is important to obtain a clearer picture of the differential impact of maltreatment subtypes (particularly, abuse vs. neglect) within samples of maltreated young people to provide accurate information to the child protection services and help them make decisions consistent with young people's needs (Petrenko et al., 2012).

Furthermore, individual differences on child abuse and neglect should be considered. Gender and age differences in child abuse and neglect (Calheiros et al., 2021; Villodas et al., 2015), psychopathology (Magalhães et al., 2016; Magalhães et al., 2018), and in the association between child maltreatment and mental health (Hagborg et al., 2017; Maschi et al., 2008) justify the inclusion of gender and age as moderators. For instance, community-based studies suggest that the negative impact of emotional maltreatment may be stronger for girls' mental well-being than boys' mental well-being (Hagborg et al., 2017), and that the relationship between maltreatment and externalizing symptoms seems to be stronger for boys (Li et al., 2019; Maschi et al., 2008). Also, preschool and preadolescent years appears to be a particularly critical developmental phase for physically abused children who present an increased risk of aggressive/rule-breaking behaviors, while sexually or neglected children are more likely to present behavioral difficulties during middle childhood (Villodas et al., 2015).

Additionally, there is evidence that young people in residential care reveal more mental health problems and lower quality of life than those who are placed in foster care (Baker et al., 2007; Damnjanovic et al., 2011). Indeed, children in foster care tend to show more positive experiences and less internalizing and externalizing symptoms than children in residential care (Li et al., 2019). Family foster care has been recognized as an important alternative service for abused and neglected children as it is based on individualized and responsive caregiving which may nurture more positive outcomes than residential care; however, residential settings may be important resources for children presenting severe disorders (Li et al., 2019).

Finally, to have a clear understanding about the role of child maltreatment on young people's outcomes in out-of-home care, data collection methods must be considered (Hambrick et al., 2014). Results with out-of-care samples have suggested that significant discrepancies are observed between self-reported measures and case records (Hambrick et al., 2014), suggesting that there are cases of maltreatment that are not captured by case records and others that are not taken by self-reported approaches (Negriff et al., 2017). Also, self-reported maltreatment seems to be associated with worse mental health outcomes compared to case reports, but the combined use of case reports and self-reported measures may enable us to identify greater rates of maltreatment than using merely one strategy (Negriff et al., 2017).

The Current Study

The paths through which child maltreatment is associated with the mental health of young people in care are complex (Pecora et al., 2009), a reason why disentangling the different effects is critical to design and implement effective services that address young people's needs. We know that child maltreatment is associated with negative mental health outcomes and that multiple maltreatment experiences are related to worse outcomes (Debowska et al., 2017; Leeb et al., 2011), but we still need to know more about how different subtypes of child maltreatment are related to these outcomes (Cecil et al., 2017; Trickett et al., 2011), and particularly in out-of-home care.

Although past systematic reviews have summarized the evidence about the association between maltreatment in residential and foster care and mental and physical health outcomes (Carr et al., 2020) or the rates of maltreatment and mental health problems in foster children (Oswald et al., 2010), to the best of our knowledge no meta-analytic reviews have been performed on the role of the history of maltreatment in mental health problems in out-of-home care. Through conducting meta-analyses we will be able to identify the types of maltreatment that produce the largest effect sizes in mental health outcomes for young people in care. Moreover, we are interested in the conditions under which child maltreatment particularly impacts young people's mental health outcomes in care, and a meta-analysis is described as an efficient method for disentangling these effects (Dworkin, 2020, p. 1012). Beyond sample characteristics (e.g., gender – boys vs. girls vs. mixed; age – only adolescents vs. children/adolescents; origin – USA vs. Europe vs. others) and placement type (i.e., residential care vs. foster care vs. mixed samples), some methodological options may alter the effect of child maltreatment on mental health outcomes (e.g., type of maltreatment measurement – CPS records vs. young people report vs. others' report; type of mental health measurement – young people report vs. others' report vs. combined).

The goals of our study were twofold: (a) to provide evidence about the role of different subtypes of child maltreatment, before their placement in care, in current internalizing and externalizing symptoms of adolescents in out-of-home care; and (b) to test the moderator role of individual, placement, and methodological variables.

Method

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A systematic electronic search was conducted in September 2022 (no limitation was set for the lower date limit) in the following databases: Academic Search Complete, PsycArticles, PsycInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, ERIC, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus. The search was restricted to peer-reviewed articles, published in academic journals, in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. The search terms included all possible combinations of the following keywords: (a) residential care OR institution* OR therapeutic care OR group home* OR foster care OR foster famil*; AND (b) child maltreatment OR child abuse OR child neglect; AND (c) mental health OR trauma OR symptoms OR psychopathology OR internalizing OR externalizing OR mental disorders; NOT (d) adults OR elderly. Based on the references of previous reviews on this subject (e.g., Carr et al., 2020; Magalhães, 2015; Magalhães & Calheiros, 2014; Oswald et al., 2010), a hand search was also performed, ensuring that relevant studies were not overlooked. This meta-analysis was not pre-registered in PROSPERO or any open access platform.

Studies were considered if they met a set of inclusion criteria: (1) empirical and quantitative studies, with correlational or longitudinal designs; (2) with school-aged children and adolescents (between 6 and 19 years-old) in out-of-home care; (3) assessing maltreatment before their placement, such as abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse; and (4) associated with outcomes of psychopathology, namely internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Studies were excluded when (1) child maltreatment experienced before the child placement was not assessed; (2) do not associate maltreatment experiences and mental health outcomes; (3) include children under 6 years old; (4) include samples of children who were not in out-of-home care, looked-after children, or were involved with the juvenile justice system; (5) do not evaluate internalizing and/or externalizing peoblems; or (6) only presented multivariate results.

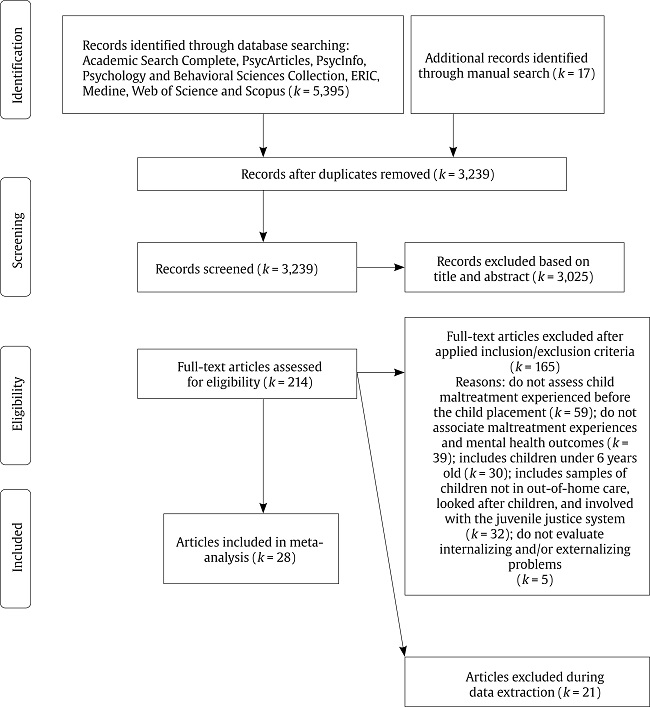

Study selection was conducted through a four-phase process (Figure 1), based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) Statement (Page et al., 2021). The screening of titles and abstracts was performed by two independent judges using the software Rayyan QCRI (Ouzzani et al., 2016). One of the raters screened all the articles identified and the other screened 25% of them, reaching an agreement of 92.56%, and all the disagreements were solved through consensus. From the 3,239 articles initially identified, 28 were selected and included in the meta-analysis (see Appendix A1). The data synthesis included a meta-analysis conducted in accordance with APA's Meta-Analysis Reporting Methods (MARS; Appelbaum et al., 2018).

Coding of Studies

Data were extracted to a form to code the main studies' characteristics, results, and the statistics required to calculate the effect sizes, in accordance with the guidelines proposed by Lipsey and Wilson (2001). The information extracted from each study was: bibliographical information (authors, title, year of publication), sample characteristics (type of participants – children and adolescents, adolescents; sex – boys, girls, both; type of placement – only residential care, only foster care, out-of-home care [residential and foster care]; age-range of the children, sample size), study characteristics (region in which the study was conducted, design), information about the variables (type of maltreatment – general maltreatment, abuse, neglect; measures of maltreatment; evaluation of internalizing and externalizing symptoms; measures of internalizing and externalizing symptoms), main results, and the respective effect sizes. The type of maltreatment was coded into three different subtypes based on the literature (e.g., Barnett et al., 1993; Mathews & Collin-Vezina, 2019; Starr et al., 1990), namely abuse – including (a) physical and emotional abuse since the primary studies reported results just for physical abuse, (b) physical and emotional abuse separately, and (c) non-specified abuse – and sexual abuse and neglect – including (a) different sub-types of neglect since the primary studies reported results just for physical neglect, (b) multiple types of neglect separately, and (c) non-specified neglect. Moreover, a general maltreatment code was used when authors from primary studies did not specified subtypes but considered on only one general dimension different types of child abuse and neglect. Internalizing symptoms (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, emotional disorders, anxious arousal) and externalizing symptoms (e.g., conduct disorder, anger control problems, hyperactivity, delinquency) were coded based on the literature previously presented (Achenbach, 1991). Whenever effect sizes were not reported in the primary studies, they were calculated from the reported statistics.

Calculation of Effect Sizes

Effect sizes were extracted or calculated for each association between a variable of maltreatment (e.g., Child Protection System [CPS] records, youth self-reports) and psychopathology (e.g., internalizing, externalizing). Since the included primary studies were correlational, Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient (r) was chosen as the effect size. Further, correlations are readily interpretable in terms of practical importance (Rosenthal & DiMatteo, 2001) and are easily computed from other statistics, such as chi-square, t, F, and d values (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004).

Correlational coefficients (when not reported) were calculated using the methods and formulas proposed by Lipsey and Wilson (2001), and by Borenstein et al. (2009). Given the need of having normally distributed values (Cooper, 2010; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001), correlation coefficients were initially transformed into Fisher's z-scores, which were transformed back to correlations after the analyses, to enhance the interpretability of the results. The direction of each effect size (either positive or negative) matched the statistical data as reported in the primary study. Effect sizes of r = .10 were interpreted as small, r = .30 as medium, and r = .50 as large (Cohen, 1977).

Analysis Plan

A random-effect- approach was applied since the studies included were treated as a random sample from a larger population of studies (see for example Camilo et al., 2020; Mulder et al., 2018). Multiple results for different types of maltreatment and for both categories of symptoms were extracted from the same primary study. For this reason, and to consider the dependency between effect sizes from the same study, a three-level meta-analysis for each type of maltreatment associated with internalizing and externalizing symptoms was conducted. Three different sources of variance were modeled: variance between studies (level 3), variance between effect sizes from the same study (level 2), and sample variance of all the effect sizes (level 1) (e.g., Assink et al., 2015; Mulder et al., 2018). The meta-analytic models were built in the R statistical environment (version 3.6.3, R Core Team, 2020), with the “rma.mv” function of the metafor package (Viechtbauer, 2010), using the syntax described by Assink and Wibbelink (2016). The model coefficients were tested two-sided using the Knapp-Hartung-correction (Knapp & Hartung, 2003), which means that individual coefficients were tested using a t-distribution, and an F-distribution was used for the omnibus-test of all coefficients in the model (excluding the intercept). Two one-sided log-likelihood-ratio tests were performed to determine the significance of the variances at levels 2 and 3, and the sampling variance of all the effect sizes (level 1) was estimated by the formula of Cheung (2014).

These multilevel models calculate an overall effect size and, if significant variance on level 2 and/or level 3 is observed, they allow to examine whether study and/or sample characteristics can explain this variance through moderation analyses. As such, a set of potential moderating variables were examined, which were firstly transformed into dummies. Moreover, similarly to Mulder et al.'s (2018) procedure, the full dataset for internalizing and for externalizing symptoms were used instead of testing potential moderators in each type of maltreatment. Finally, nonparametric and funnel-plot based trim-and-fill analyses were conducted (Duval, 2005) for bias diagnostic (i.e., publication bias).

Results

Descriptive Results

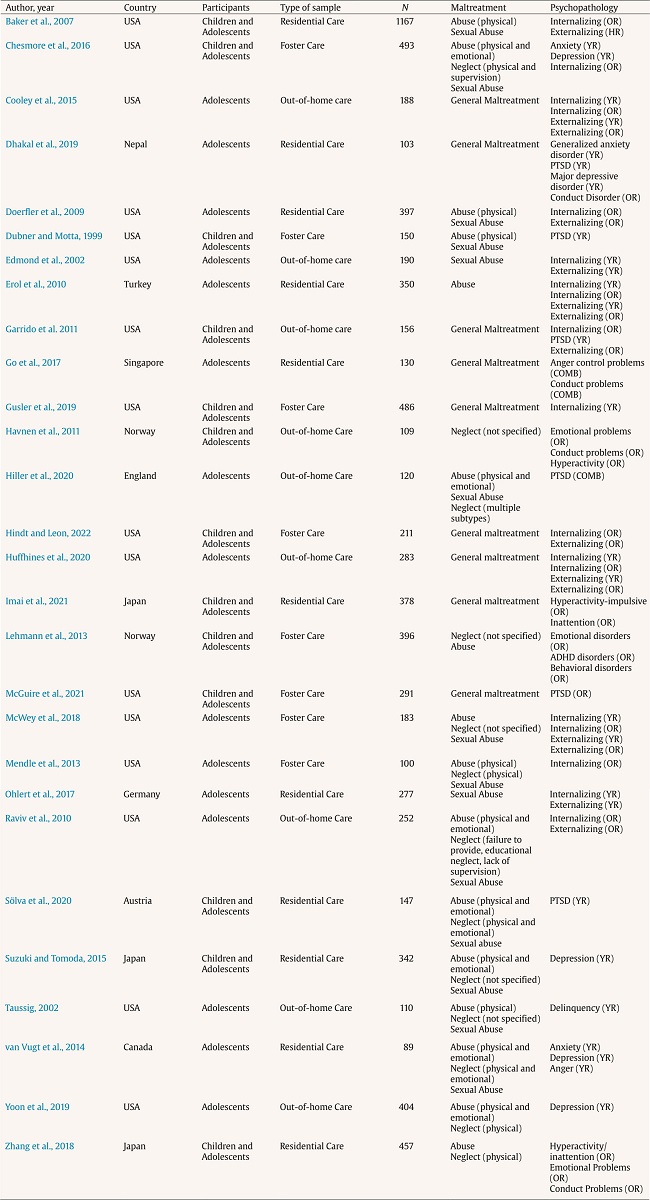

The present review analyzed a total of k = 28 articles and 122 effect sizes (see Appendix A1). Most studies were conducted in the USA (k = 16), followed by Europe (k = 6), and Japan (k = 3), and single studies were conducted in Nepal (k = 1), Singapore (k = 1), and Canada (k = 1).

The samples included mostly adolescents (k = 14) or children and adolescents (k = 14), in residential care (k = 11), foster care (k = 8), or mixed samples in out-of-home care (k = 9), and the sample sizes ranged from n = 89 to n = 1,167 (Ntotal = 7,959). Most of the studies were conducted with both boys and girls (k = 23), and others just with girls (k = 5) or boys (k = 2). Regarding the type of maltreatment, the primary studies analyzed abuse (physical and/or emotional; k = 16), sexual abuse (k = 14), neglect (physical, emotional, educational; k = 13), and a smaller number of studies explored general maltreatment (k = 9). Child maltreatment was assessed mostly through CPS records (k = 13) and youth self-report measures (k = 8), and less studies used other-reports (k = 3) or combined different sources of information (k = 2). Symptoms were coded into two domains – internalizing (k = 26) and externalizing (k = 19). The primary studies assessed internalizing and externalizing symptoms through youth self-report measures (k = 17), other-reports (k = 17), or combined (k = 2).

Overall Effects of Maltreatment on Internalizing and Externalizing

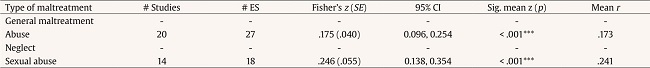

The overall effect for each type of maltreatment on internalizing symptoms is presented in Table 1. The overall effects of general maltreatment (r = .260), sexual abuse (r = 247), and abuse (r = .135) on internalizing symptoms were significant but small. The overall effect size observed for neglect was not significant (r = .060).

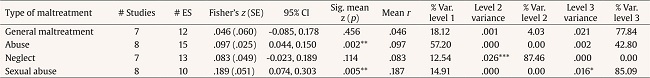

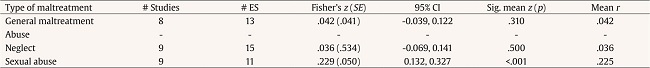

Regarding externalizing symptoms, the overall effect of each type of maltreatment is presented in Table 2. While the overall effects of abuse (r = .097) and sexual abuse (r = .187) were significant but small in magnitude, the overall effect sizes observed in general maltreatment and neglect were not significant (r = .046 and r = .083 respectively).

Table 1. Results for the Overall Mean Effect Sizes of the Types of Maltreatment in Internalizing Symptoms.

Note.# Studies = number of studies; # ES = number of effect sizes; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval for Fisher's z; sig. mean z = level of significance of mean effect size; mean r = mean effect size (Pearson's correlation); % var = percentage of variance; level 2 variance = variance between effect sizes within studies; level 3 variance = variance between studies.

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

Table 2. Results for the Overall Mean Effect Sizes of the Types of Maltreatment in Externalizing Symptoms.

Note.# Studies = number of studies; # ES = number of effect sizes; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval for Fisher's z; sig. mean z = level of significance of mean effect size; mean r = mean effect size (Pearson's correlation); % var = percentage of variance; level 2 variance = variance between effect sizes within studies; level 3 variance = variance between studies.

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

Heterogeneity and Moderator Effects

Results of the likelihood-ratio tests showed significant level 2 (between effect sizes from the same study) and level 3 (between studies) variance. Considering all effect sizes in one dataset for internalizing symptoms and another dataset for externalizing symptoms (see Method section), the log-likelihood ratio tests for both revealed significant variance on level 2 (internalizing, p < .001; externalizing, p < .001) and level 3 (internalizing, p < .001; externalizing, p = .017) of the multilevel meta-analytic models. Therefore, we proceeded with testing variables as potential moderators using the full datasets (Table 3 and Table 4).

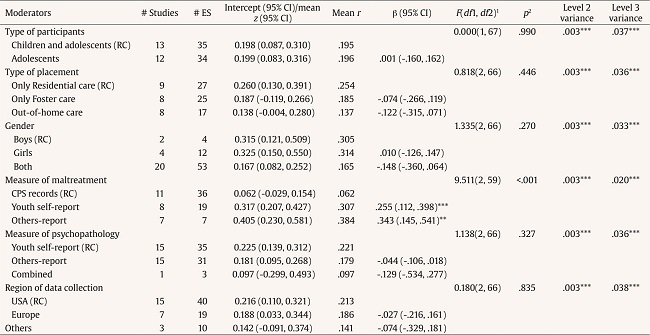

Table 3. Results for Categorical Moderators (Bivariate Models) – Internalizing.

Note.# studies = number of studies; # ES = number of effect sizes; mean r = mean effect size (r); CI = confidence interval; β = estimated regression coefficient; RC = reference category; level 2 variance = variance between effect sizes within studies; level 3 variance = variance between studies.1Omnibus test of all regression coefficients in the model; 2p-value of the omnibus test.

***p < .001.

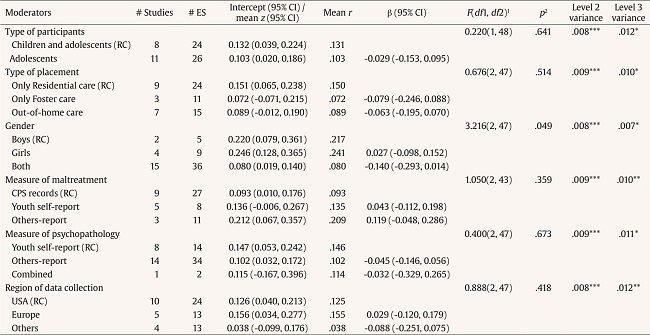

Table 4. Results for Categorical Moderators (Bivariate Models) – Externalizing.

Note.# studies = number of studies; # ES = number of effect sizes; mean r = mean effect size (r); CI = confidence interval; ß = estimated regression coefficient; RC = reference category; level 2 variance = variance between effect sizes within studies; level 3 variance = variance between studies.

1Omnibus test of all regression coefficients in the model; 2p-value of the omnibus test.

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

For internalizing symptoms, a moderation effect was found for the measure of maltreatment, with the studies using youth self- (r = .307) and others-reports (r =.384) showing stronger effects than those using CPS-records (r = .062). Regarding externalizing symptoms, a moderation effect was found for gender with studies with combined samples of boys and girls (r = .080) showing weaker effects than those with female samples (r = .241).

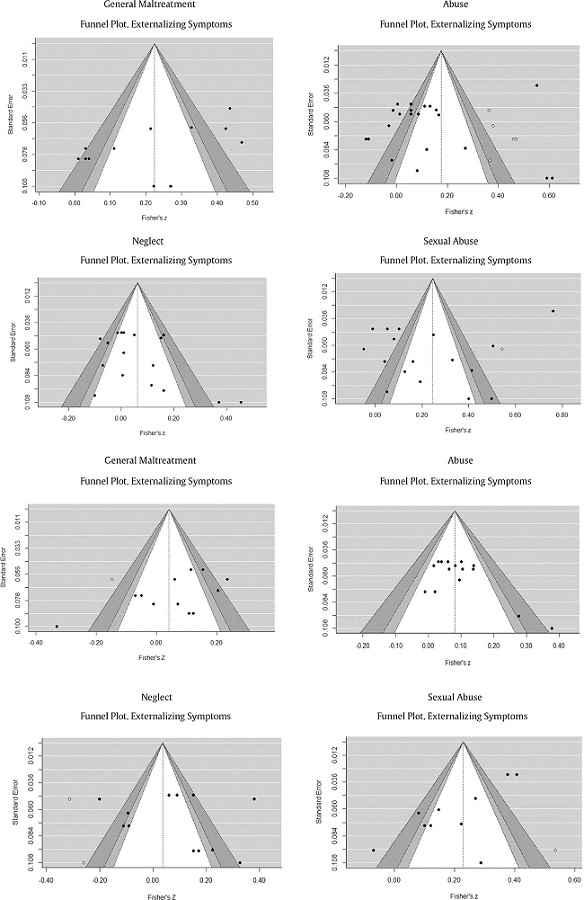

Trim and Fill Analyses

The trim and fill analyses, plus the observation of distribution asymmetry of funnel plots (Appendix A2), suggest that bias was present in most types of maltreatment in internalizing and externalizing. Therefore, the overall effects were adjusted by imputation of “missing” effect sizes and re-estimation of the overall effect, presented in Tables 5 and 6. For internalizing, abuse and sexual abuse showed higher effects. For externalizing, sexual abuse showed a higher effect, while general maltreatment and neglect showed smaller effects.

Table 5. Results for the Overall Mean Effect Sizes of the of the Types of Maltreatment in Internalizing Symptoms After Conducting Trim and Fill Analyses.

Note.# studies = number of studies; # ES = number of effect sizes; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval for Fisher's z; sig. mean z = level of significance of mean effect size; mean r = mean effect size (Pearson's correlation).

***p < .001.

Table 6. Results for the Overall Mean Effect Sizes of the of the Types of Maltreatment in Externalizing Symptoms After Conducting Trim and Fill Analyses.

Note.# studies = number of studies; # ES = number of effect sizes; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval for Fisher's z; sig. mean z = level of significance of mean effect size; mean r = mean effect size (Pearson's correlation).

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

Discussion

This meta-analysis aimed to identify the maltreatment types that produce the largest effect sizes in mental health outcomes for young people in out-of-home care as well as the conditions affecting these effects. These objectives were accomplished using 122 estimates obtained from 28 studies and 7,959 participants. Findings suggested that the largest effect sizes were found on sexual abuse, both for internalizing (medium) and externalizing (small) symptoms, which is consistent with evidence suggesting the particular deleterious effect of sexual abuse (Debowska et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2016; Maniglio, 2015). Young people in care who had experienced a sexually abusive event revealed higher psychological difficulties than their peers (Doerfler et al., 2009), and the role of sexual abuse on behavioral problems remains significant after considering potential confounding factors (e.g., gender, socioeconomic status; Maniglio, 2015). The stronger effect of sexual abuse on internalizing than externalizing symptoms that we found is consistent with the literature revealing the considerable impact of sexual abuse on anxiety, particularly posttraumatic stress symptoms (Hébert & Amédée, 2020; Maniglio, 2013). Neurobiological and psychological factors seem to explain these anxiety symptoms, given that the sexually abusive experience may undermine brain functions and amplify victims' hypervigilance for threatening stimuli (Maniglio, 2013). As such, the victims' appraisal of sexual abuse might explain these internalizing symptoms. Following sexually abusive experiences, these victims may develop internal attributions or self-blame cognitions focused on individual stable attributes that in turn are related to higher symptoms (Feiring et al., 2002). Cognitive psychological perspectives suggest that these internal, stable, and global attributions may also lead to feelings of shame, which might explain poor victims' psychological functioning (Freeman & Morris, 2001).

Furthermore, this meta-analysis revealed that abusive experiences (emotional and/or physical) were also positive and significantly related to internalizing and externalizing symptoms, but the effect size was also larger on internalizing symptoms. In fact, (sexual and physical) abuse seems to show robust and unique effects on mental health difficulties when controlling for other events (Conte & Vaughan-Eden, 2018). Emotionally abusive experiences negatively impact the child basic needs for love, belonging, and safety (Hart et al., 2018), which can explain these symptoms. Abused children and adolescents may show emotional regulation difficulties that explain their symptoms (Dvir et al., 2014). Following abusive experiences, these children and adolescents may learn that they should be self-reliant as their caregivers are not trustful (Barker & Hodes, 2007). Moreover, the effect of physical abuse on a child's externalizing symptoms has been largely described in the literature (Felson & Jane, 2009) and grounded on the social learning theory (Bandura, 1978). According to the literature, physically abused children may be more prone to engage in aggressive behaviors based on the abusive parental modeling (Felson & Jane, 2009).

Additionally, general maltreatment was positive and significantly related to internalizing but not to externalizing symptoms. Internalizing symptoms following maltreatment may stem from the disruption of secure internal representations of maltreating caregivers (Dvir et al., 2014). The non-significant results found on externalizing symptoms may be explained by the nature and content of the general maltreatment dimension. This general dimension of maltreatment includes different subtypes – physical, emotional, sexual abuse and neglect. As we found stronger effects of physical and sexual abuse on internalizing symptoms, we assume that the cumulative effect of these abusive experiences on internalizing symptoms remains significant even with the whole construct. However, for externalizing symptoms, the effect was smaller when considering solely physical/emotional abuse and sexual abuse and the strength weakened when the whole dimension was considered in the analyses.

The current findings corroborate the equifinality assumption as different types of maltreatment (sexual, emotional, and physical abuse) may be associated with similar outcomes (internalizing and externalizing symptoms), but some distinction regarding the subtypes of maltreatment was also found, because the effect sizes of neglect were not statistically significant. First, some authors proposed that neglected children desire close relationships and may avoid being rejected, which may be associated with lower externalizing symptoms (Finzi et al., 2002; Maguire et al., 2015). Second, the absence of significant effects for neglect may be related with the subtypes of neglect explored in the reviewed studies (i.e., mostly physical or the lack of supervision) as well as the outcome explored in this meta-analysis (i.e., internalizing and externalizing symptoms). During adolescence, physical neglect seems to be associated with poor academic achievement, delinquency, or school dropout, but emotional neglect seems to generate more profound consequences, namely, suicidality, mental health disorders, or delinquency (Ericksson et al., 2018). Emotional neglect involves the parental failure to be responsive and psychologically available, which might be related with long-lasting emotional and behavioral problems (Ericksson et al., 2018). Evidence with normative samples highlighted that emotional neglect has a stronger impact on adolescents' mental well-being (Hagborg et al., 2017).

Moderating analyses reveal a significant effect regarding the type of maltreatment measure for internalizing symptoms, meaning that the studies using youth self- and other-reports showed stronger effects than those using CPS-records. This finding supports the conclusion from a systematic review conducted by Carr et al. (2020), which suggested that certain measures may be more sensitive to capturing negative psychological outcomes of child maltreatment. As such, the results might vary according to the type of measurement (Sierau et al., 2017; Trickett et al. 2011), and CPS records do not capture all forms of abuse and neglect experienced by children across time. Also, as we know that some maltreatment experiences are not captured by self- or other-reports, combined procedures of CPS-records and reports may enable a more accurate picture of maltreatment rates and outcomes (Negriff et al., 2017). This is particularly useful considering internalizing symptoms, given that they are less visible and therefore more dependent on child and adolescent' self-report. It is also important to note that the greater effects for self- and other-reports may be associated with greater shared variance between maltreatment and internalizing reports, if completed by the same informant.

Furthermore, a moderation effect of gender for externalizing symptoms was found in studies with female samples showing stronger effects than those with combined samples (males and females). Surprisingly, no differences were found between boys and girls as expected (Li et al., 2019). Gender differences in externalizing symptoms have been widely reported in the literature over decades, with boys presenting more problems than girls, both using self- or other-reports (Leadbeater et al., 1999; Lewis et al., 2016). However, gender differences regarding the impact of maltreatment on mental health outcomes, and particularly over time, need further understanding. Some authors found that the psychopathology of girls in care significantly increased over time, but this was not true for boys (Weis & Toolis, 2009). If externalizing behaviors are more prevalent in boys than girls, their occurrence in girls are perceived as more dysfunctional (Doerfler et al., 2009; Hussey & Guo, 2002). Additionally, as we found in this meta-analysis that child sexual abuse was the stronger predictor of externalizing difficulties and given that girls tend to be more victims of sexual abuse than boys (Finkelhor et al., 2014), this result can be partially explained by the role of this abusive experience on externalizing symptoms (Doerfler et al., 2009).

All these findings propose that professionals working in the out-of-home care system need to have suitable knowledge about children's history of traumatic experiences, over and above their current mental health needs, with a particular attention to gender specific needs (Van Vugt et al., 2014). Bearing in mind the developmental trauma as an explanation for psychological difficulties in out-of-home care (Oswald, 2010), trauma informed treatments should be delivered (Hagborg et al., 2017), providing individual and tailored intervention based both on gender and abuse (Doerfler et al., 2009). Findings from this review highlighted the detrimental effects of child maltreatment on mental health outcomes in out-of-home care (particularly the impact of sexual abuse), which calls for trauma-informed intervention approaches. This means delivering interventions where this impact of trauma is considered (American Association of Children's Residential Centers, 2014). Despite the promising findings, these results should be interpreted with caution, since the effects sizes of our meta-analyses are small to moderate.

Strengths and Limitations

The current meta-analysis has several strengths. It provides new insights beyond previous systematic reviews (Oswald et al., 2010), as we were able to identify the effects sizes of the associations between maltreatment and internalizing and externalizing problems in out-of-home care children and adolescents. Furthermore, we included eight databases, a comprehensive group of keywords which resulted in 122 effect sizes, and the role of individual and contextual moderators. We surpassed potential problems of effects sizes' dependency using a multilevel approach (Assink & Wibbelink, 2016) and we analyzed the effects' heterogeneity exploring potential moderators (Borenstein et al., 2009). However, this study also has limitations. Regarding the maltreatment subtypes, we did not include other forms of maltreatment (e.g., interparental violence; domestic violence exposure), derived from some inconsistencies on the definitions of exposure to interparental violence (Gardner et al., 2019). In addition, aspects of timing, chronicity, and severity of maltreatment should be considered in the future. Beyond maltreatment, other risk factors may contribute to the mental health of children and young people in care (Oswald et al., 2010), a reason why additional moderators should be explored in the future (e.g., length of placement in care, age of admission in care, number of placements/moves in the alternative care system). Concerning methodological limitations, we did not assess the methodological quality of studies. Nevertheless, our meta-analyses did not include nonpublished studies, which could lead to biased results, since studies with statistically significant results are more likely to be published (Borenstein et al., 2009). In addition, the inclusion of studies with small samples could heighten the effects of publication bias (e.g., Turner et al., 2013). However, potential biases were addressed through the diagnosis analysis of funnel plots asymmetry and the trim-and-fill method. Finally, a significant number of studies (k = 22) presented only multivariate data and for that reason they were not included. Longitudinal designs are also needed to provide further evidence on the causality and directions of associations between trauma and psychological outcomes.