Introduction

Dating Violence (DV) is a serious issue that affects adolescents worldwide (Collibee et al., 2021; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014; Leen et al., 2013; Vives-Cases et al., 2021; Wincentak et al., 2017), with a global prevalence for adolescents aged 13-18 years of 20% for physical violence and 9% for sexual violence (Wincentak et al., 2017). DV is associated with several negative consequences for adolescents' health and well-being, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder or substance abuse (Molero et al., 2022; Molero et al., 2023; Park et al., 2018; Ramiro-Sánchez et al., 2018; Taquette & Monteiro, 2019; Wincentak et al., 2017). Victims of DV may also experience fear of starting new relationships, difficulties in communicating with their partners or isolation (Park et al., 2018).

The literature on adolescent DV has highlighted the important role of attitudes toward this type of violence (Duval et al., 2020; Reyes et al., 2016; Rubio-Garay et al., 2015; Vagi et al., 2013). Attitudes are understood as beliefs, social norms related to perceived severity, acceptability, and tolerance of DV (Edwards et al., 2022). Research has shown that tolerant attitudes toward DV are related to greater subsequent DV perpetration among adolescents (Brendgen et al., 2002; Courtain & Glowacz, 2021; Foshee et al., 2001; Josephson & Proulx, 2008; McCauley et al., 2013; Vagi et al., 2013). Others' attitudes of tolerance toward DV may also lead to adolescent victims to feel personal guilt and shame. As a result, they may receive less support and help that may, in turn, reinforce the perpetrator's violent behavior (Niolon et al., 2017).

Research has generally focused on four sets of public perceptions and attitudes toward intimate partner violence: acceptability, legitimacy, attitudes toward intervention, and perceived severity (Gracia et al., 2020; Villagrán, Santirso et al., 2023). However, the perceived severity of this violence has received the least scholarly attention even though it is an important factor associated with important issues related to this type of violence, including the public's acceptance or tolerance of it, individuals' sense of personal responsibility, attitudes toward intervention, and reactions to incidents of this kind of violence among victims, professionals and bystanders (Gracia et al., 2020).

Perceived DV severity has also been considered a risk factor for this type of violence. For example, qualitative research has shown that lower perceived DV severity is linked with greater DV acceptability, more justification of violence, lesser likelihood of victims seeking help and lower bystander intervention (Bowen et al., 2013; Casey et al., 2017; Cho et al., 2023; Edwards et al., 2022; Rojas-Solís & Romero-Méndez, 2022; Smith et al., 2005). Adolescents who perceive low levels of DV severity are also less likely to intervene to prevent DV recurrence (Casey et al., 2017; García-Díaz et al., 2018). Although previous qualitative studies have addressed perceived DV severity in adolescents, it is rarely their main focus. Hence more research assessing the perceived severity of this type of violence is still needed (Black & Weisz, 2004; Bowen et al., 2013; Storer et al., 2020). Psychometrically sound instruments are key for accurately assessing perceived DV severity in adolescents. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no validated quantitative instruments that specifically address the perceived severity of DV among adolescents. The appropriate assessment of perceived DV severity can contribute to better inform and assess the effectiveness of interventions to prevent DV among adolescents (Leen et al., 2013; Robles et al., 2015; Rojas-Solís & Romero-Méndez, 2022).

The Present Study

The purpose of this study is to adapt and validate the Perceived Severity of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women scale (PS-IPVAW; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022) to the adolescent population. The PS-IPVAW has appropriate psychometric properties and has been widely used in a variety of contexts for several purposes and with different adult samples (general population, IPVAW offenders and law enforcement professionals) (Catalá-Miñana et al., 2013; El Sayed et al., 2020; Expósito-Álvarez et al., 2021; Gracia et al., 2011, 2014; Lila et al., 2013; Lila et al., 2019; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, & Lila, 2018; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, Marco, et al., 2018; Martín-Fernández et al., 2021, 2022; Sani et al., 2018; Vargas et al., 2017; Villagrán et al., 2020, 2022; Villagrán, Martín-Fernández, et al. 2023; Vitoria-Estruch et al., 2017). In the intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW) context, the perceived severity of this type of violence has been related to other relevant constructs, such as empathy, ambivalent sexism and victim-blaming attitudes (Gracia et al., 2011; Lila et al., 2013; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, & Lila, 2018; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022).

For validation purposes, the adaptation of the PS-IPVAW to the adolescent population is also conducted by exploring its relations with the same set of theoretically relevant variables (i.e., with victim-blaming attitudes, sexist attitudes and empathy). Victim-blaming attitudes justify and legitimize violence against women in certain circumstances (Gracia, 2014). These attitudes are important because perceptions of who is responsible for violence influence public responses (Gracia et al., 2009; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, & Lila, 2018: Taylor & Sorenson, 2005; Waltermaurer, 2012). These attitudes may influence other key factors of DV, such as acceptability of violence, less support for the victims from their informal social network, or aggressors fostering violent behaviors (Gracia, 2014; Gracia et al., 2018; Taylor & Sorenson, 2005; Waltermaurer, 2012). For sexist attitudes, previous studies have documented a close relation between these attitudes and perceived IPVAW severity (Martín-Fernández et al., 2022; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, Marco, et al., 2018; Villagrán et al., 2022). Ambivalent sexism has also been identified as a key factor related to DV (Dosil et al., 2020; Erdem & ahin, 2017; Fernández-Antelo et al., 2020; Guerra-Marmolejo et al., 2021; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2022; Morelli et al., 2016; Olcay & Yeşiltepe, 2023). In this regard, research has linked adolescent DV with higher hostile and benevolent sexism levels (Guerra-Marmolejo, 2021). Finally, empathy is a multidimensional construct that includes cognitive and emotional aspects and has been linked with social competence and violent behavior (Endresen & Olweus, 2001; Halberstadt et al., 2001; Martos Martínez et al., 2021). Several studies conducted with adolescents have found that empathy is negatively associated with violent behavior (Euler et al., 2017; Hartmann et al., 2010; Martos Martínez et al., 2021; Vachon et al., 2014). Other studies have linked empathy with other types of violence, such as bullying (Carmona-Rojas et al., 2023; Espelage et al., 2018; Euler et al., 2017; Hartmann et al., 2010; Zych et al., 2018).

Given the importance of the availability of reliable and valid instruments for research and prevention in the DV field, the present study, first, examines the latent structure and internal consistency of the Perceived Severity of Adolescent Dating Violence (PS-ADV) scale; second, evidence for the validity of this instrument is assessed. Finally, a gender invariance analysis is conducted to ensure the comparability of the PS-ADV scores between boys and girls.

Method

Participants

The sampling method used to collect the dataset was a two-stage stratified cluster sampling. First, all the public and private secondary schools in a region of Spain (Valencia) were selected. Of them, three public and three private schools were then selected. Second, five groups from each school were randomly selected to participate in the present study. The initial sample consisted of 1,048 adolescents. After removing the responses from the participants who did not respond to questionnaires or who had missing socio-demographic data, the final sample consisted of 921 adolescents.

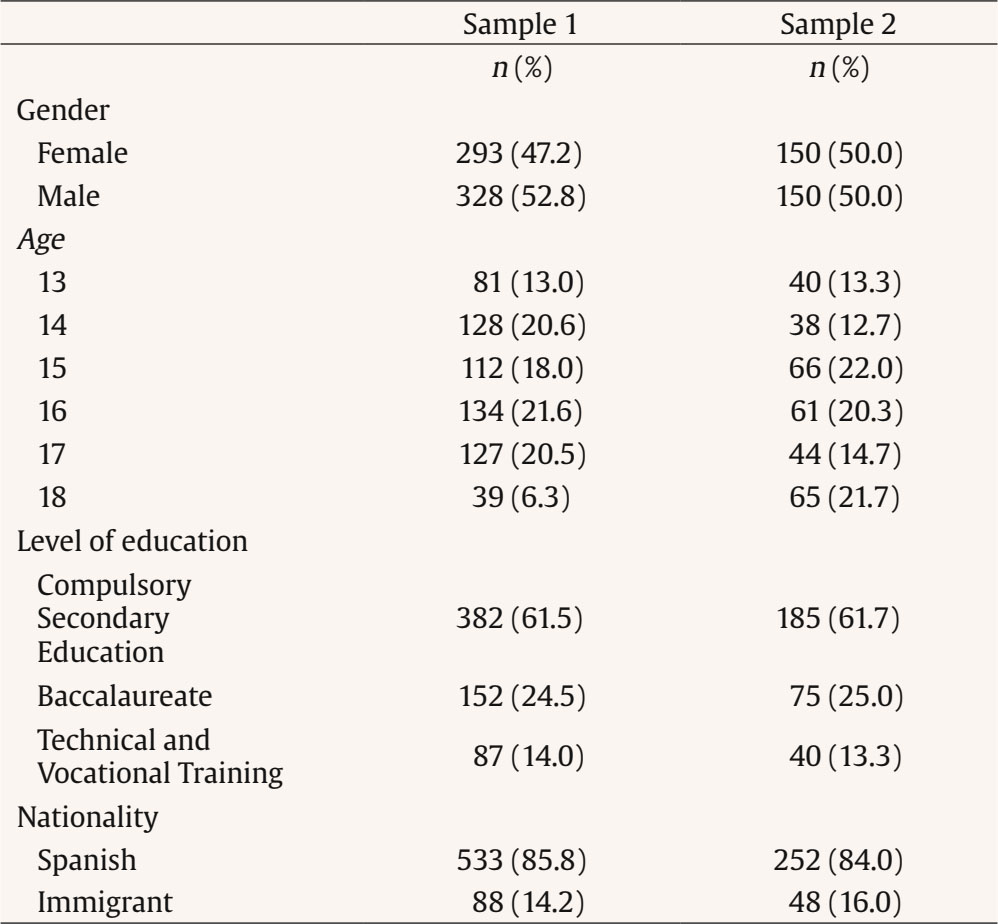

We used two samples for the present study. The first sample was used to assess the psychometric properties of the PS-ADV scale. It comprised 621 participants (47.2% girls) aged 13-18 years (M = 15.34, SD =1.49). The second sample was used to assess the measurement invariance of the scale across genders. This sample included 300 additional high school students (50% girls) aged 13-18 years (M = 15.33, SD =1.55). The socio-demographic characteristics of both samples are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of Sample 1 and Sample 2

Note. The level of education reflects the students attending each level. In the Spanish educational system, Compulsory Secondary Education comprises 10 years of formal education, Baccalaureate 12 years of formal education, and Technical and Vocational Training 11 or 12 years of formal education. In sample 1, Immigrant includes 55.7% students of Latin American nationalities, 19.3% European, 14.8% African, and 10.2% Asian; in sample 2, immigrant nationality is as follows: 60.4% Latin American, 22.9% European, 14.8% African, and 12.5% Asian.

Measures

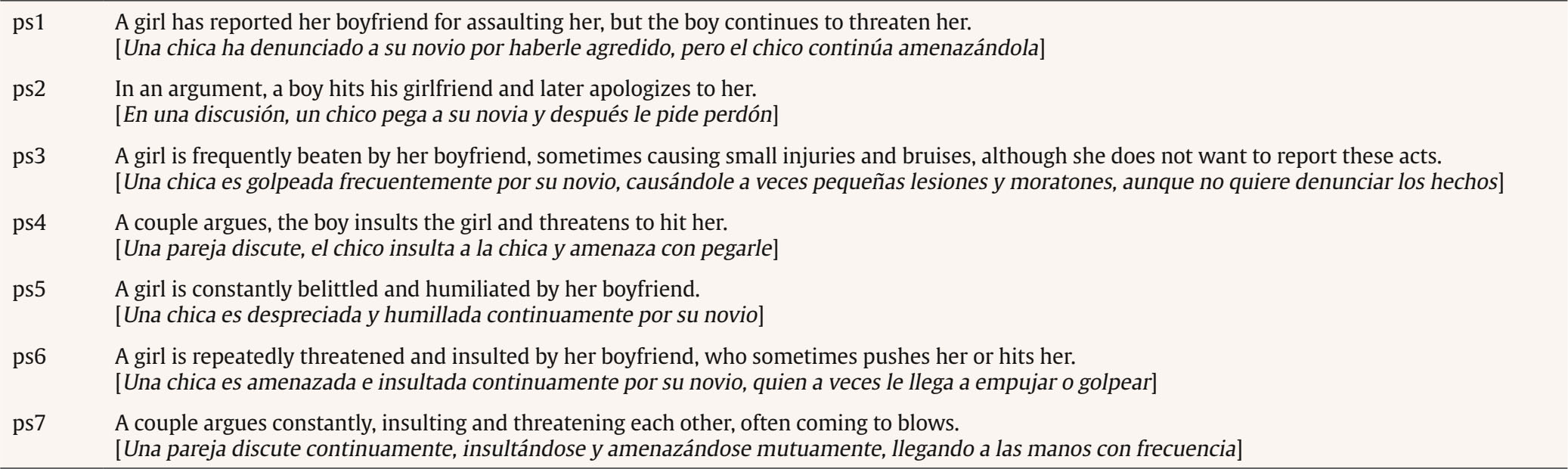

Perceived Severity of Adolescent Dating Violence (PS-ADV) Scale. We adapted and subsequently validated the Perceived Severity of Intimate Partner Violence against Women scale (PS-IPVAW; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022) to an adolescent population. To adapt the PS-IPVAW, a panel of four experts reviewed the items to adapt them to dating violence. First, two experts adjusted the language of items (e.g., “In an argument, a boy hits his girlfriend and later apologizes to her”). The other two experts evaluated their clarity and representativeness for assessing the construct. Second, items were discussed in a focus group with all the experts and the final version of the scale was determined (Appendix). This instrument consists of seven items in which an item presents a DV scenario (e.g., “A girl has reported her boyfriend for assaulting her, but the boy continues to threaten her”). Respondents were asked to rate the severity of each scenario on a scale from 0 to 10 (the higher the number, the more severe the scenario is rated).

Victim-blaming Attitudes in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence against Women Scale (VB-IPVAW; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, & Lila, 2018). The VB-IPVAW scale comprises 12 items with which respondents have to indicate their level of agreement with each one (e.g., “Boys are violent toward their girlfriends because girls need to be controlled”) on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = strongly disagree, 3 = strongly agree). This scale has been validated in a Spanish population and is closely linked to other related constructs such as ambivalent sexism, and attitudes toward intervention (Gracia et al., 2018; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, & Lila, 2018). This instrument showed good internal consistency (α = .88).

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI; Glick & Fiske, 1996). In this study, we used the adolescent Spanish version (Lemus-Martín et al., 2008). This inventory has two 10-item subscales. The hostile sexism subscale refers to attitudes of prejudice and discrimination against girls based on their perceived inferiority to boys (e.g., “Girls are too easily offended”). Benevolent sexism is defined as an attitude that stereotypes girls and limits them to certain roles (e.g., “A boy can feel incomplete if he doesn't date a girl”). This measure consists of a 6-point Likert-type response format (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). This inventory has been adapted and validated in different countries and populations (Etchezahar, 2012; Glick et al., 2000; Glick & Hilt, 2000; Glick et al., 2002; Ibabe et al., 2016; Lemus-Martín et al., 2008; Rudman & Glick, 2012). The internal consistency of both subscales and the total scale was good for the first sample and the second sample (αhostile = .88, αbenevolent = .84, ωtotal = .94, ωhostile = .91, ωbenevolent = .83).

Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Brief Form (IRI; Davis, 1980; Ingoglia et al., 2016). The Spanish version of items was used (Carrasco et al., 2011). The brief form of the IRI includes four subscales: a) empathic concern evaluates emotional reactions to others' negative experiences (e.g., “I often have tender feelings and concern for people less fortunate than myself”); b) perspective taking, that assesses respondents' ability to understand the other person's point of view (e.g., “Before I criticize someone, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place”); c) personal distress, that addresses emotional reactions of discomfort when observing others' negative experiences (e.g., “I tend to lose control during emergencies”); and d) fantasy, that focuses on the ability to identify oneself with fictional characters in novels or movies (e.g., “I truly identify with the feelings of the characters in a novel”). The brief version includes 16 items with a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). One item from the empathic concern subscale (item 9) was removed because its item-total corrected correlation was almost zero (r = -.01). This scale has been validated in a Spanish population (Carrasco et al., 2011; Pérez-Albeniz et al., 2003) and has been linked to partner violence (Lila et al., 2013; Romero-Martínez et al., 2019). The overall internal consistency of this measure and its subscales was adequate (αempathic concern = .66, αperspective taking = .70, αpersonal distress= .78, αfantasy scale = .82, ωtotal = .91, ωempathic concern = .65, ωperspective taking = .78, ωpersonal distress = .78, and ωfantasy scale = .87).

Procedure

A survey was designed to collect data in a face-to-face setting. It included the PS-ADV scale, the VB-IPVAW scale, the ASI, and the IRI. In addition, questions were asked about some socio-demographic data (e.g., age, gender, nationality, school, current grade at high school, socio-economic level, whether they had a partner). Participants were informed of the purpose of the study and the anonymity of the data, which were collected before completing the survey. The high schools in the study were informed of the study prior to data collection, which took place from November 2021 to May 2022. This study was approved by the University of Valencia Ethics Committee.

Data Analysis

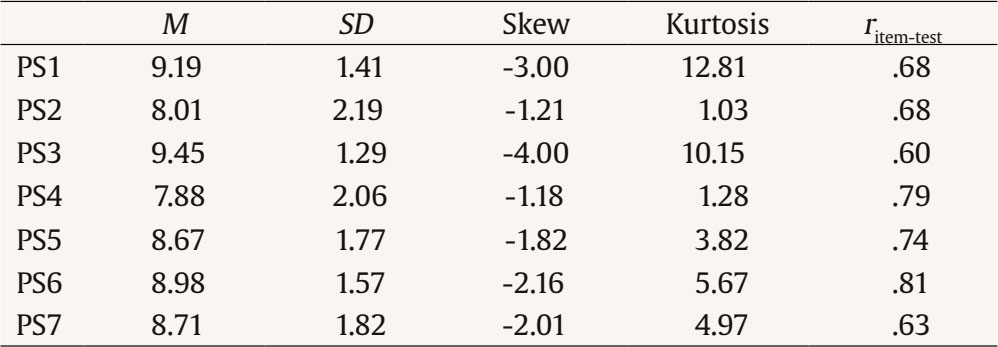

The following analyses were conducted in the first sample to assess the psychometric properties of the PS-ADV. First, a descriptive analysis was carried out by computing the mean, standard deviation, skew and kurtosis statistics, and the item-total corrected correlation for each item.

We then tested the factorial structure of the scale by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and replicating the one-factor model found in previous studies with adult populations (Martín-Fernández et al., 2022; Villagrán et al., 2023). We used robust maximum likelihood (MLR) as the estimation method because this procedure yields accurate parameter estimates for non normally distributed data (Bandalos, 2014; Nalbantoğlu-Yılmaz, 2019). The model's goodness of fit was evaluated by using a combination of fit indices: values of the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis's index (TLI) equaling or above .95, and values of the root mean squared error by approximation (RMSEA) equaling or lower than .06 or .08 were considered to be an excellent or good fit, respectively (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Once the factor structure was established, we examined the scale's internal consistency using Cronbach's α. The validity evidence of the PS-ADV was inspected later by relating participants' factor scores to other relevant attitudinal constructs, such as ambivalent sexism, victim-blaming attitudes and empathy.

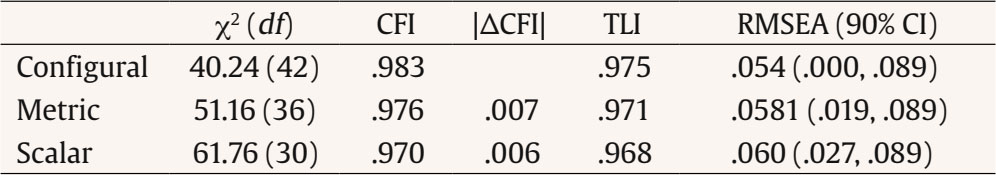

We finally assessed the scale's measurement invariance across gender using a second sample and conducting a multigroup CFA because carrying out this analysis with the same sample can yield overestimated fit indices for the factorial model. To this end, we tested configural, metric, and scalar invariance (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). Configural invariance evaluates whether participants conceptualize the construct (i.e., perceived severity) in a similar way by ensuring that the same factorial structure can be applied for boys and girls. Metric invariance tests if items have the same factor loadings in both groups, and if items present similar relevance for boys and girls. Scalar invariance assesses whether the same response pattern yields the same factor scores for boys and girls by fixing item loadings and intercepts to the same value across groups. We used MLR as an estimation method and compared all the models by means of the log-likelihood ratio test (LRT) and Cheung and Rensvold's (2002) guidelines for continuous data. In particular, we deemed the instrument to be invariant across gender if the following criteria were met: a) there were no significant differences among the configural, metric, and scalar invariance models in the LRT; b) the difference in the comparative fit index (∆CFI) was lower than .001 between the configural and metric models, and between the metric and scalar models. If scalar invariance was achieved, then the latent means of the measured construct could be compared across gender.

All the analyses were carried out in the statistical package R (R Core Team, 2023) using the psych library (Revelle, 2023), and Mplus 8.4 for the CFA and the multigroup CFA (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The descriptive statistics of the PS-ADV items obtained mean values above 8.00, with standard deviation around 1.70 for most items, which indicates that most participants rated the scenarios depicted by items as severe. The skew and kurtosis statistics depicted how participants' responses were concentrated mainly on the upper extreme of the response scale, which showed a leptokurtic and negatively skewed distribution for most items (Table 2). We also found that the item-test corrected correlations were high for all the items, which indicates a close relation between each item and the direct scores of the scale.

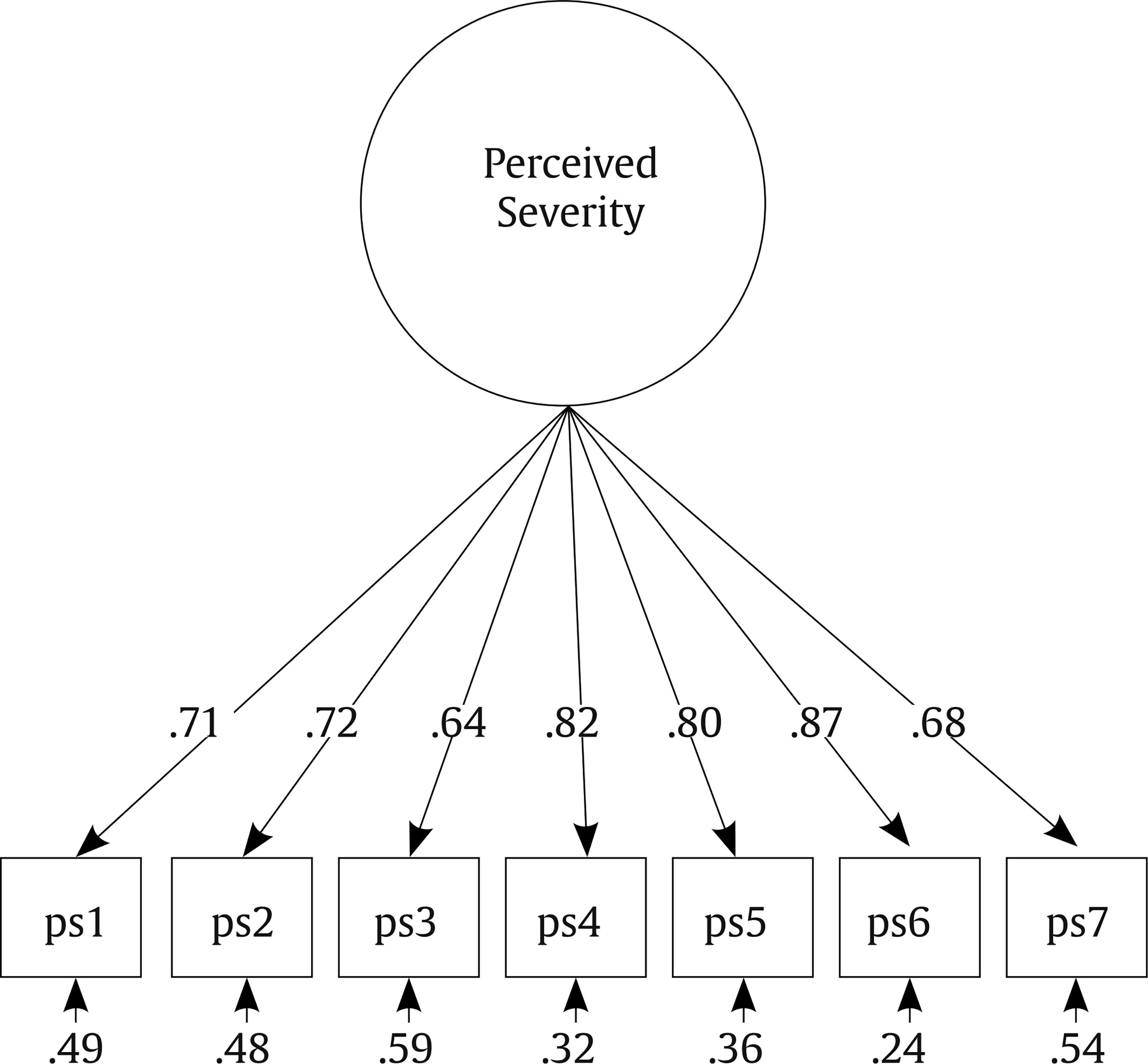

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Internal Consistency

We conducted a CFA by replicating the one-factor model found in the adults version of the scale (Martín-Fernández et al., 2022). The one-factor model's goodness of fit was adequate (CFI = .96, TLI = .94, RMSEA [90% CI] = .074 [.062, .087]), which indicates that one factor was enough to account for the variability of the PS-ADV. The standardized factor loadings were above .60 for all the items, which supports the notion that all the items were closely related to the measured construct (Figure 1). We found that the scale's internal consistency was good (α = .89).

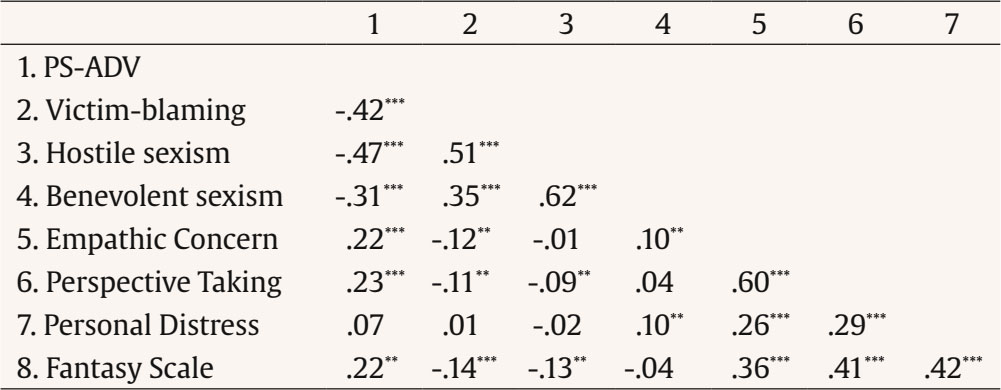

Validity Evidence

Using the factorial scores, we explored thereafter the relation of perceived severity to other IPVAW-related constructs, such as victim-blaming attitudes, ambivalent sexism, and empathy (Table 3). We found a close significant and negative relation between the PS-ADV scores and victim blaming, hostile sexism, and benevolent sexism. In particular, our data showed that the participants with higher perceived severity levels had, on average, lower levels of victim-blaming attitudes. A similar trend was found for ambivalent sexism, where the participants presenting higher levels of perceived severity tended to also show lower levels of both hostile and benevolent sexism. For empathy, we found a significant and positive relation between participants' PS-ADV scores and the subscales of the IRI perspective taking, fantasy, and empathic concern. This indicates that the participants with higher perceived severity levels tended to present higher levels on these dimensions. No relation was found between the PS-ADV scale and the personal distress subscale.

Measurement Invariance

The measurement invariance of the PS-ADV across gender was evaluated by means of a multigroup CFA in the second sample (Table 4). We first examined configural invariance as a base-line model and found that it showed excellent goodness of fit to data. This result implies that the same factorial model could be applied for girls and boys. We then tested metric invariance by fixing item loadings to the same value for girls and boys. We also found an excellent goodness of fit and no significant differences between configural and metric invariance in the LRT, ∆χ2SB(6) =10.43, p = .107; |∆CFI| = .007. This, in turn, supports the notion that metric invariance could be held. After establishing metric invariance, scalar invariance was assessed by constraining the item intercepts for girls and boys to the same value. The well model fitted the data. Once again, we did not find any significant differences between metric and scalar invariance, ∆χ2SB(6) =11.77, p = .067; |∆CFI| = .006.

Table 4. Measurement Invariance Fit Indices

Note. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean-squared error by approximation.

Once scalar invariance was supported, we conducted a latent mean analysis to compare girls and boys' latent means. The model yielded an excellent goodness of fit (CFI = .97, TLI = .97, RMSEA [90%CI] = .065 [.035, .093]), and showed that girls had higher perceived severity levels than boys (Z [SE] = 0.733 [0.156], p < .001). In particular, a standardized mean difference of 0.733 indicated that 76.8% of the girls presented higher perceived severity levels than the average for boys.

Discussion

In this study, we set out to adapt and validate a widely used instrument for assessing the perceived severity of IPVAW in adults (PS-IPVAW; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022) to the adolescent population. The results obtained in latent structure and reliability terms showed that the instrument replicates the one-factor model of the original scale (Martín-Fernández et al., 2022) and has good internal consistency, which means that it accurately assesses the measured construct, i.e., the perceived severity of DV, in the adolescent population.

For the analysis of invariance across gender, the results of this study indicated that both girls and boys shared the same conceptualization of the perceived severity of DV. There were no differences in the structural parameters of items (i.e., loadings and thresholds) between boys and girls. This finding means that the interpretation of items was similar and, therefore, both groups were comparable because the same response pattern yielded identical results for boys and girls. Our results also revealed that boys tended to perceive DV scenarios as less severe than girls, which is consistent with previous research in the IPVAW context (Dardis et al., 2017; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022; Villagrán et al., 2022).

For validity evidence, we analyzed the relationship between adolescents' perceived severity of DV, victim-blaming attitudes, ambivalent sexism, and empathy. Our findings showed that perceived severity was related to these three constructs. For victim-blaming attitudes, we found a significant negative relation between perceived severity and victim-blaming attitudes, which indicates that the adolescents who perceived DV scenarios as less severe were more likely to show higher levels of victim-blaming attitudes. Our results are consistent with previous research that has linked perceived severity with attitudes of victim-blaming in the IPVAW context (Gracia et al., 2018; Lelaurain et al., 2021; Martín-Fernández, Gracia, & Lila, 2018; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022; Villagrán et al., 2020, 2023).

On sexist attitudes, our results also showed a significant negative relation between perceived severity and ambivalent sexism. The adolescents who perceived lower DV severity in scenarios presented higher hostile and benevolent sexism levels. These results coincide with previous research, which has indicated that perceived severity is related to both hostile and benevolent sexism in adult populations (Lelaurain et al., 2021; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022; Villagrán et al., 2023). Guerra-Marmolejo et al. (2021) found a similar trend among adolescents, where sexist attitudes were related to the perception and acceptance of violence against women. This is also consistent with previous research that has linked ambivalent sexism and DV perpetration (Dosil et al., 2020; Erdem & ahin, 2017; Fernández-Antelo et al., 2020; Guerra-Marmolejo et al., 2021; Morelli et al., 2016; Olcay & Yeşiltepe, 2023).

Concerning empathy, our results showed that the adolescents with higher levels of perceived DV severity tended to also present higher empathy levels, especially for its cognitive aspects. Our results specifically indicated a positive relation between perceived severity of DV and the perspective taking and fantasy subscales of the IRI. The adolescents with high perceived severity of DV tended to empathize more with fictional characters, and also showed a greater ability to put themselves in the other person's place. We also found a significant positive relation between perceived severity and empathic concern that, in turn, indicated that the adolescents who perceived more severity in scenarios were better able to identify when others experience negative events. This result is congruent with previous findings showing a positive relation between empathy and perceived severity in adults (Lila et al., 2013), and between empathy and attitudes toward aggression in adolescents (Martos Martínez et al., 2021). This is also consistent with previous studies with adolescents, and indicates that the lower the empathy level, the higher the likelihood of engaging in violent behaviors (Euler et al., 2017; Hartmann et al., 2010; Martos Martínez et al., 2021; Vachon et al., 2014). Although this relation between perceived severity and empathy seems promising for developing intervention strategies, further research is needed to explore the direct effect of empathy on perpetrating DV (Dodaj et al., 2020; Romero-Martínez et al., 2016).

This study is not without some limitations. First, as the PS-ADV was developed with a sample of adolescents in the Spanish cultural setting, and we cannot generalize our findings to other cultural contexts. Further research is needed to examine the psychometric properties of the PS-ADV in other socio-cultural contexts and to examine how it relates to other relevant constructs (Villagrán, Santirso, et al., 2023). Second, the cross-sectional design of our study prevented us from controlling possible changes in participants' perceived severity over time. Third, DV does not occur in isolation and is often associated with other issues during adolescence that are not addressed in the present study. Adolescence has been identified as a period of greater psychosocial vulnerability or difficulty compared to childhood and adulthood (Reyes et al., 2023; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). At a time of decreased parental influence and increased peer influence, adolescents interact with each other without adult supervision (Alcaide et al., 2023; Baumrind, 1991). Psychosocial vulnerability in adolescence is reflected not only in increased risk for violent behavior (e.g., dating violence), but also in greater difficulties in school (Steinberg & Morris, 2001; Veiga et al., 2023) and other maladaptive behaviors (e.g., early substance use) (Martinez-Escudero et al., 2023; Villarejo et al., 2023). Previous research has confirmed that DV is associated with other serious psychosocial adjustment problems (Campo-Tena, 2023; Exner-Cortens, 2013).

Our findings have important implications for policy and practice. To our knowledge, this is the first study that aims to validate a self-reported scale assessing the perceived severity of DV among adolescents. Previously, qualitative assessment measures have been used to assess perceived DV severity with adolescent samples (Black & Weisz, 2004; Bowen et al., 2013; Storer et al., 2020). Moreover, our findings extend knowledge on the association between perceived DV severity and victim-blaming attitudes, ambivalent sexism, and empathy. Changing adolescents' attitudes and beliefs about DV is an important intervention goal in DV prevention programs (Crooks et al., 2019). To this end, such programs often use intervention strategies to address the perceived severity of DV, such as discussion of romantic love myths and role-playing to promote healthy violence-free dating relationships. In line with this, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have included adolescents' attitudes toward DV among their measures to assess the effectiveness of interventions (De la Rue et al., 2014, 2017; Edwards & Hinsz, 2014; Fellmeth et al., 2015; Lee & Wong, 2020; Ting, 2009). However, the assessment of attitudes makes it difficult to compare different studies due to the diversity of the instruments used to measure attitudes toward DV. In addition, when measured, attitudes toward DV are usually assessed as a broad concept and specific measures are not contemplated, such as perceived severity and victim-blaming attitudes in adolescents. Further studies should be conducted to evaluate how these attitudes are related to other risk factors that may contribute to the complex multifaceted event of DV. Assessments of these attitudes may further help to identify adolescents at risk for DV, which could help to tailor interventions to the specific needs of these more vulnerable populations (Arrojo et al., 2023; Crooks et al., 2019; Ferreira et al., 2022; Piolanti & Foran, 2021; Reyes et al., 2020).

The development of the PS-ADV is an important step in the study of attitudes toward DV. This instrument may be useful in research to better understand the DV phenomenon, its impact on other relevant constructs, and to identify factors that increase or decrease the risk of DV. The PS-ADV is a short measure that is easy to implement and may be valuable for assessing perceived severity in the general population of adolescents in large-scale studies in which time of application and space are limited, such as demographic surveys (Gracia et al., 2018; Martín-Fernández et al., 2021, 2022). This instrument could also be used to test the effectiveness of programs and interventions that aim to prevent DV in both educational and community settings. The PS-ADV scale could also be used to monitor whether there has been an impact on adolescent attitudes following awareness campaigns and prevention policies (Gracia et al., 2023; Gracia et al., 2020), and could be useful for identifying adolescents at risk of DV and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions and prevention strategies that address this vulnerable population.