Introduction

One of the main objectives of the family is to help children develop confidence and acceptance of themselves as valuable persons in different areas of life. Studying parental socialization based on a theoretical model characterized by two dimensions (i.e., warmth and strictness) and four parental styles (i.e., authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful) allows identifying the optimal parental style for child development across the world. However, much of the research on parenting is based on studies conducted in Western societies, primarily in the United States (Brown et al., 1993; Lamborn et al., 1991) and Europe (Calafat et al., 2014; Fuentes et al., 2019), and the optimal parenting style may not necessarily be the same across all cultures (Pinquart & Kauser, 2018; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). This means that benefits of parenting style that combine strictness and warmth (the authoritative style) which have been identified from studies conducted with European-American parents (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994) may not be applicable to Eastern societies. The present study aims to examine the relationship between parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful) and both the self-esteem and self-concept (academic, social, emotional, family, and physical) of adolescents and young adult children from a relatively unexplored culture of Asia: Chinese families from the People's Republic of China.

Two-dimensional Theoretical Model with Four Parenting Styles

For decades, the study of parental socialization has been conducted using a theoretical framework with two orthogonal or unrelated dimensions (i.e., warmth and strictness) and four parenting styles (i.e., authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful) (Lamborn et al., 1991; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Warmth refers to the extent to which parents show affection or warmth, and the level of involvement with their children (Gimenez-Serrano, Alcaide et al., 2022; Martinez et al., 2019). Other labels that share the meaning of warmth include responsiveness (Baumrind, 1983), acceptance (Symonds, 1939), love (Schaefer, 1959), care (Orlansky, 1949; Watson, 1928), nurturance (Freud, 1933), or acceptance/involvement (Steinberg et al., 1994). Strictness refers to the extent to which parents use strict rules and limits, tend to apply physical and/or verbal corrections, as well as demanding practices (Dakers & Guse, 2020; Martinez et al., 2017). Other labels that share the meaning of strictness include demandingness (Baumrind, 1991), hostility (Baldwin, 1955), domination (Symonds, 1939), inflexibility (Sears et al., 1957), supervision (Steinberg et al., 1994), control (Schaefer, 1959; Watson, 1928), or firm control (Steinberg et al., 1989). Four parenting styles were defined by examining the combined effects of warmth and strictness: authoritarian (characterized by strictness without warmth), authoritative (characterized by strictness and warmth), indulgent (characterized by warmth without strictness), and neglectful (characterized by a lack of strictness and warmth).

The Optimal Parenting Style

Much research, mainly conducted in the US with European-American families, reveals the benefits of strictness when accompanied by warmth (i.e., authoritative parenting) (Baumrind, 1967; Baumrind, 1971; Lamborn et al., 1991; Mounts & Steinberg, 1995; Steinberg, 2001; Steinberg, Lamborn, et al., 1992). Authoritative parenting is related to some benefits such as good school grades (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Steinberg, Lamborn, et al., 1992), greater maturity and development (Steinberg, 2001; Steinberg et al., 1989), less behavioral problems (Fletcher et al., 1995; Steinberg et al., 1991), and decreased drug use (Baumrind, 1991; Steinberg et al., 1991). However, the benefits of the authoritative parenting style may not be common to all contexts and settings (Palacios et al., 2022; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). Some research conducted in the United States with ethnic minorities, such as African American (Baumrind, 1972; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996), Hispanic American (Pinquart & Kauser, 2018; Zayas & Solari, 1994), and Asian-American (Chao, 1994, 2001) has revealed certain benefits of parental strictness without warmth (authoritarian parenting). For example, authoritarian parenting has detrimental consequences on European-American children, but not on African American children (Deater-Deckard et al., 1996), who even report advantages such as assertiveness and independence (Baumrind, 1972).

Asian-American families have received special attention given how they tend to prioritize preserving their culture of origin, which can be different from that of the host country (i.e., US) in certain aspects (Chao, 1994, 2001). In this context, authoritarian parenting seems to not be related to harmful consequences in Asian-American individuals and even adolescents raised in authoritarian families do very well in school (Chao, 1994, 1996, 2000, 2001), especially those from China, Japan, and South Korea (Chao, 2000). As Chao (2000) points out, Asian-American adolescents from authoritarian families tend to maintain the highest grades. In the same line, some research conducted in poor and risky neighborhoods also identified some benefits associated with authoritarian parenting (Baldwin et al., 1990; Furstenberg et al., 1999).

In addition, results on the optimal parenting style reveal inconsistent empirical findings; authoritative parenting is not always related to universal benefits (Chao, 2001; Palacios et al., 2022). To explain these discrepant findings on optimal parenting styles, some studies suggest the importance of social and cultural context (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). It is speculated that, despite having the same parents, there may be variations in the degree to which children feel loved, valued, and strongly connected to their family (i.e., the so-called family self-perceptions) depending on the specific background (Baumrind, 1972; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996; Martinez et al., 2021). For instance, among ethnic minorities, who are more likely to live in more dangerous neighborhoods with fewer opportunities, the use of strictness, despite the lack of warmth, could make children find in their parents the security and protection that the community does not offer (Baldwin et al., 1990; Furstenberg et al., 1999). It is argued that in authoritarian homes (characterized by less warmth and more strictness), European-American children may feel that their parents are intrusive, unloving, and uncaring, while African-American children may feel loved, valued, and recognized by their family (Baumrind, 1972; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996).

Chinese Culture: Limited Research and Mixed Results on Optimal Parenting

In any part of the world it is possible to study parenting based on warmth and strictness and its relation to child adjustment. However, optimal parenting, mainly studied in Western countries (e.g., United States and Europe), may not be the same for Eastern countries. Families in Eastern societies, including Asian and Arab cultures, are raising children within a cultural context that is typically characterized by collectivist and vertical values (Rudy & Grusec, 2001; Triandis, 1989). The individual (e.g., the child) might be a part of a collective (e.g., the family) in which the relationships between the members (e.g., parents and child) are hierarchical and non-egalitarian (Chen et al., 1997; Dwairy et al., 2006; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). Traditional societies (e.g., Turkey or China) seem to have especially delimited social roles. Relationships tend to be lower on egalitarianism, but higher on power distance, which could be related in the context of the family to a higher frequency of the use of strictness, but less of warmth. However, unlike in Western countries, the relationship with parents based on authority and discipline could be accepted by the children (Kisbu et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023).

Within Asian societies, China has been studied for decades in part due to its cultural characteristics especially influenced by Confucianism (Chao, 1994; Leung et al., 1998) and the pursuit of jen as the core virtue of life (Chen et al., 2020). According to the principles of Confucian thought, an individual is defined by his or her relationships with others, relationships are organized hierarchically, and social order and harmony are preserved if each party fulfills the responsibilities and requirements of role relationships (Chao, 1994; Ho, 1986; Leung et al., 1998). In the Chinese culture, parents and children are expected to assume certain roles to keep the home running smoothly and to foster family harmony (Ho, 1986; Leung et al., 1998; Yang, 1986). Parents are required to govern, teach, and discipline their children (e.g., chiao shun and guan) (Chao, 1994; Nelson et al., 2006), whereas children are required obey, honor, and respect their parents (e.g., filial piety) (Leung et al., 1998; Wu & Chao, 2011). Because of family interdependence, child adhering to socially desirable and culturally approved behavior directly affects the family as a whole (Ho, 1986; K. Yang, 1986). For example, academic success is especially valued in Chinese families (Chen & Uttal, 1988; Sue & Okazaki, 1990). If children perform poorly academically, they will have disappointed their parents, but also parents will have failed in socialization by being inadequate rulers and caretakers of their family (Chao, 1994, 2000). It has been suggested that parenting based on parental strictness and authority, without making use of involvement and warmth, fits very well with Chinese cultural traits (Ho, 1986). However, empirical findings about the optimal parenting style among Chinese families offer mixed results.

On the one hand, some evidence seems to suggest benefits associated with a parenting style characterized by strictness without warmth (i.e., the authoritarian style) (Chao, 1994, 1996, 2000, 2001). In this sense, studies with immigrant families in the United States (the so-called Chinese-American homes) have revealed that authoritarian parenting is associated with important benefits, especially academically (Chao, 1994, 2001). However, for their counterparts from European-American families, authoritarian parenting is related to poor developmental outcomes (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994). Other scholars, who have examined ethnic differences in adolescent achievement in the United States, indicate that Chinese-American and other Asian students had the highest grades regardless of family type (maybe due to the cultural repercussions of doing well in school) (Steinberg, Dornbusch, et al., 1992).

The benefits of authoritarian parenting are also found in some studies conducted in China (Ekblad, 1986; Leung et al., 1998; Li et al., 2010; Quoss & Zhao, 1995). Compared to children from Western countries, it is possible that children from the People's Republic of China (PRC) might feel loved, valued, and protected by their family (the collective) even though their parents tend to be stricter and show less warmth (e.g., praising, hugging, and kissing the child) (Chao, 2000). In this sense, the authoritarian style appears to have no detrimental consequences and is even associated with positive outcomes, such as family satisfaction (Quoss & Zhao, 1995), less depression (Li et al., 2010), and good school adjustment (Ekblad, 1986; Leung et al., 1998; Li et al., 2010). However, benefits related to authoritarian parenting practices have been identified (e.g., using shame to correct sons), without considering the relationship of parental practices with the two dimensions (Ekblad, 1986). Another limitation is that parenting styles are based on global measures for each style (mainly authoritative and authoritarian), but without considering the two main dimensions and the four types of families (Leung et al., 1998; Li et al., 2010; Quoss & Zhao, 1995).

On the other hand, emergent research from China, mainly focused on parenting practices, also seems to suggest the benefits of parental strictness accompanied by high warmth (i.e., authoritative parenting) (Chen et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2000; Xia et al., 2015). According to these studies, parenting practices that define the authoritative parenting (i.e., the authoritative style), such as those found in European-American families, seem to also be positive in the People's Republic of China (PRC) (Wang et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2004). However, comparisons are mainly limited to some parenting practices corresponding to authoritative or authoritarian parenting styles without considering the two dimensions (i.e., warmth and strictness) to define the four parenting styles (Chen et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2004). Additionally, some inconsistent results have been described when the effect of authoritarian practices are examined. For example, monitoring and involvement (common to authoritative parents) were related to more school adjustment and less behavioral problems, but parental support (a parental practice based on greater warmth) was surprisingly related to more behavioral problems (see Xia et al., 2015). The limited emergent evidence seems to detect the positive effect of discipline and surveillance (parental strictness), but within a relationship based on dialogue, affection, and trust between parents and children (parental warmth) (Xia et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2017).

Toward a Cross-cultural Paradigm Based on Three Parenting Stages

Optimal parenting may not be the same all over the world (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). Currently, a new paradigm of optimal parenting has been suggested based on three historical stages, extending the traditional paradigm of only two stages (i.e., authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles) to include the indulgent parenting style (for a review, see Garcia et al., 2019). According to the old paradigm, two optimal stages of optimal parenting (i.e., authoritative and the authoritarian parenting) have been suggested over the past century. The first historical stage corresponded to the benefits of parenting characterized by strictness without warmth (i.e., the authoritarian style). At the beginning of the last century, John B. Watson (Watson, 1928) advised parents about the risk of spoiling their children with unnecessary displays of warmth, while proposing strict parenting to get children to develop regular habits and self-discipline. Laurence Steinberg (Steinberg, 2001) supports the idea that, for contemporary industrialized societies, parenting based on strictness is effective only when combined with warm parenting (i.e., the authoritative style or second stage). Furthermore, current emergent research in the digital era seriously questions if parenting based on strictness is still needed to achieve the highest child and adolescents' personal and social well-being. The three stages occur simultaneously in different contexts, settings, and cultures, so for each specific context the optimal one must be analyzed.

Specifically, the so-called third stage of optimal parental socialization (i.e., the indulgent style) seems to have empirical support based on a growing body of research mainly conducted in European and Latin American countries (Calafat et al., 2014; Climent-Galarza et al., 2022; Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Garcia & Serra, 2019; Martinez & Garcia, 2007, 2008; Martinez et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2013; Villarejo et al., 2020). In contrast to the main findings from studies with European-American families, parenting based on warmth without strictness (i.e., the indulgent style) is associated with optimal scores in different indicators of adjustment and competence such as self-concept and self-esteem (Martinez & Garcia, 2007; Perez-Gramaje et al., 2020), cognitive and affective empathy (Fuentes et al., 2022), less drug use (Riquelme et al., 2018; Villarejo et al., 2023), including motivations for drinking and non-drinking (Garcia, Serra, et al., 2020), greater internalization of social values and environmental values (Queiroz et al., 2020), school achievement, and other academic outcomes (Fuentes et al., 2019; Reyes et al., 2023). In this sense, it seems that the indulgent style might be associated with equal or even more positive scores than the authoritative style. It is possible that adolescents might especially benefit from close relationships with their parents based on warmth, without strictness (Martinez-Escudero et al., 2023). Some emergent results extend the benefits of the third emerging stage (i.e., warmth without strictness) beyond adolescence (Garcia, Serra, et al., 2018; Martinez-Escudero et al., 2020; Martinez-Escudero et al., 2023). Indulgent parenting seems to be associated with positive scores once parenting socialization is over, throughout adulthood (Alcaide et al., 2023; Palacios et al., 2022). As in adolescence, adult children who were raised by warm but not strict parents during the socialization years exhibit good adjustment and competence according to different indicators (Climent-Galarza et al., 2022; Garcia, Fuentes, et al., 2020; Gimenez-Serrano, Garcia, et al., 2022).

The Present Study

Regardless of the cultural and country context, it is important to detect optimal parenting styles, especially in Eastern societies, which are based on different cultural norms and values than Western ones. Contemporary China has undergone significant social, cultural, and economic changes that might affect families (Li, 2020). As Li (2020) summarized in her review, Chinese parents traditionally were expected to act as emotionally distant educators and disciplinarians of their children, but the role of parents has evolved during modern social transformations from the Confucian hierarchical ideal based on parental authority and child obedience to more egalitarian relationships between family members. Today, in Chinese societies, parents are more involved in child-rearing and warmer with their children than their predecessors. However, the optimal Chinese parenting based on warmth and strictness (i.e., authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful) still remains unclear. Additionally, family studies in People's Republic of China (PRC) have serious methodological shortcomings, and even discrepant and contradictory empirical findings.

One of the most important goals of parental socialization is for children to achieve self-confidence as competent members of their society (Baumrind, 1978; Maccoby, 1992; Veiga et al., 2023). Self-esteem arises from an overall appraisal of oneself as a valuable person with good qualities (Gudjonsson & Sigurdsson, 2003; Rosenberg, 1965) and is associated with important benefits for health and well-being as well as protection against emotional and behavioral problems (Coopersmith, 1967; Ybrandt & Armelius, 2010). However, not all children develop a good confidence in themselves and in their abilities. Low self-esteem is related to broad aspects of maladjustment. The lower the self-esteem, the higher the likelihood of aggressive behaviors, including proactive and reactive aggression (Yang et al., 2023). Meta-analytic evidence suggests that low self-esteem may have a significant potential negative impact on real-world life experiences, rather than merely being an epiphenomenon of failure in relevant life domains (Orth et al., 2012). Low self-esteem is related to high levels of negative affect, health problems, poor satisfaction with life, depression, and anxiety (Orth & Robins, 2013; Orth et al., 2012; Sowislo & Orth, 2013).

But global self-worth is formed from appraisal in different relevant personal areas (i.e., self-concept) (Chen et al., 2020; Garcia, Martinez, et al., 2018; Marsh & Martin, 2011; Shavelson et al., 1976). Self-perceptions as a competent student who is able to adapt to school demands (the so-called academic self-concept) are positively related to school performance (Marsh & Martin, 2011; Veiga et al., 2015), as well as being processes conducive to learning (Marsh & Shavelson, 1985; Musitu-Ferrer et al., 2019). However, lower academic self-concept is associated with higher likelihood of problems in school and low academic achievement (Marsh & Martin, 2011). Additionally, the correct adjustment of the individual to society also requires other dimensions of self-concept which are quite relevant (Esnaola et al., 2020). The non-academic components of self-concept (social, emotional, family, and physical) have also been positively associated with well-being and psychosocial adjustment (Fuentes et al., 2020; Fuentes et al., 2011). By contrast, low social self-concept is a risk factor for drug use (Fuentes et al., 2020) and low levels of emotional self-concept are associated with likelihood of anxious insecure attachment (Cornella-Font et al., 2020), whereas low family and physical self-concept are associated with increased risk of childhood trauma (Cornella-Font et al., 2020) and eating disorders (Maiz & Balluerka, 2018), respectively.

The present study analyzes the relationship between parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful) and scores among adolescent and young adult children based on one unidimensional (self-esteem) but also multidimensional approach which includes the academic dimension (academic self-concept) and other non-academic but highly relevant dimensions for personal and social adjustment (social, emotional, family, and physical self-concept). Low self-esteem and self-concept are not only explained by parenting, but also by broad intrafamily and extrafamily influences, as well as multiple biological, personal, social, and cultural factors (Harter et al., 1993; Orth et al., 2012; Shavelson et al., 1976). However, despite the multiple influences, parenting has consistently been identified as a protective or risk factor for self-concept and self-esteem problems (Fuentes et al., 2020; Lamborn et al., 1991; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Probably due to the importance of academic achievement in Asian culture, many studies in Chinese families have focused on academic outcomes (e.g., grade point average), without considering other relevant adjustment criteria. Another limitation of previous studies is examining the effect of parental socialization only while it is occurring (e.g., in adolescents), but not beyond, once parental socialization has ended (in adult children). It is expected that parenting styles characterized by high warmth (authoritative and indulgent) would be related to more self-esteem and self-concept (academic, social, emotional, family, and physical) than those parental styles without warmth (authoritarian and neglectful).

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample was composed of 1,282 participants ranging from 12 to 31 years of age (M = 17.68, SD = 3.37), 676 females (52.7%) and 606 males (47.3%). Participants included 581 adolescents (45.3%) ranging from 12 to 18 years (M = 15.08, SD = 3.14) and 701 young adults (54.7%) ranging from 19 to 31 years (M = 19.84, SD = 1.53). The software G-power 3.1 was used to estimate the statistical power (Faul et al., 2009). The a priori power analysis revealed that a lowest sample of 1,200 participants was needed to identify the medium-low effect size usually described for parenting styles, f = . 12 (Cohen, 1977; Garcia et al., 2008; Lamborn et al., 1991) based on a statistical power of .95 (Type I and Type II errors, α = .05; 1 - β = .95). Considering the study's sample size (N = 1,282, α = β = .05), a sensitivity power analysis indicated that statistically significant differences with a slightly lower small effect size can be detected in the main effects between the four parenting styles (f = .116) (Cohen, 1977; Garcia, Martinez, et al., 2018; Lamborn et al., 1991).

The adolescent participants were recruited from high schools. The heads of all potential participating high schools were invited to participate. When a high school declined the invitation, another school was selected until completing the sample size required (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Riquelme et al., 2018). Young adults were recruited in undergraduate education courses (Garcia et al., 2021; Manzeske & Stright, 2009). This study follows ethic principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data were compiled by using an online survey. The survey consisted of mandatory questions. To guarantee data protection measures, identifiers of participants, as well as survey data, were gathered in different and separate archives; sensitive files were protected and passwords to web directories were stored in an encryption-protected system (Garcia et al., 2021). The questionnaires were studied for doubtful response patterns, such as describing implausible inconsistencies between responses in positively and negatively worded items (Garcia et al., 2011; Garcia et al., 2021; Tomás & Oliver, 2004). All participants in the present study were Chinese-speaking, as were their parents and four grandparents, had received approval from their parents (in the case of adolescents), had given written consent, and anonymity of their responses was assured.

Measures

Parenting Styles

Parental Warmth was assessed with the 20 items included in the Warmth/Affection Scale (WAS) of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) (Rohner et al., 1978). The WAS scale evaluates the degree to which children perceive their parents as loving, responsive, and involved. Example of items are “Let me know they love me” and “Talk to me in a warm and loving way” [“他们会向我展示他们爱我” and “他们用亲密的方式与我交流”]. The alpha value was .922. Parental strictness was assessed with the 13 items included in the Warmth/Affection Scale (WAS) of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) (Rohner et al., 1978). The PCS scale evaluates the degree to which children perceive their parents are strict and exert control over their behavior. Example of items are “Tell me exactly how to do my work” [“他们会清楚地告诉我该如何做事”] and “Insist that I do exactly as I am told” [“他们坚持要我按照他们要求的方式做事”]. The alpha value was .769. Young adults answered the adult version of the WAS and PCS. Both the WAS and PCS have a 4-point response scale ranging from 1 = almost never is/was true to 4 = almost always is/was true. Previous research has shown that the WAS and PCS for adolescent and adult children are measures with very good psychometric properties that have been used in over 60 cultures worldwide, including China (Khaleque & Ali, 2017; Khaleque & Rohner, 2002; Khaleque & Rohner, 2012; Rohner, 2005). Higher scores on both WAS and PCS scales express higher parental warmth and strictness.

Parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful) were defined by splitting the sample on parental warmth and parental strictness by median-split procedure (i.e., 50th percentile) based on sex and analyzing the two parenting variables simultaneously (Alcaide et al., 2023; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994). Authoritarian families scored above the median on strictness, but below on parental warmth. Authoritative families scored over the median on both warmth and strictness. Indulgent families scored above the median on warmth, but below on strictness. Neglectful families scored below the median on both parental variables.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed using the Rosenberg Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). It consists of 10 statements that evaluate overall feelings of self-worth and self-acceptance. Example of items are “I am able to do things as well as most other people” [“我有能力和别人做的一样好”] and “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself” [“通常来讲,我对自己很满意”]. It follows a 4-point response scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Higher rates in the scale express higher self-esteem. Cronbach's alpha value for this scale was .788.

Self-concept

Self-concept based on academic and non-academic dimensions (social, emotional, family, and physical) was measured with the Chinese AF5 Multidimensional Self-Concept Scale (Chen et al., 2020). The AF5 scale was designed to evaluate self-concept based on five dimensions: academic, social, emotional, family, and physical (Garcia & Musitu, 1999; Garcia, Martinez, et al., 2018). The academic subscale evaluates how one perceives their role performance as a good student (or worker). An example of an item is “I do my homework well (professional works)” [“我的工作(学业)很出色”]. The social subscale evaluates how one perceives their performance in social and interpersonal relationships. An example of an item is “I make friends easily” [“我很容易交到朋友”]. The emotional subscale evaluates how one perceives their emotional state and their responses to specific situations. An example of an item is “Many things make me nervous” [“很多事情让我感到很紧张”]. The family subscale evaluates how one perceives their participation, integration, and involvement in the family. An example of an item is “My family is disappointed with me” [“我的家人对我感到失望”] (reversed item). The physical subscale evaluates how one perceives their own appearance and physical condition. An example of an item is “I take good care of my physical health” [“我照顾我的外型”]. The AF5 has good psychometric properties (Chen et al., 2020; Fuentes et al., 2011; Garcia, Martinez et al., 2018; Murgui et al., 2012; Tomás & Oliver, 2004). Both exploratory factorial (Garcia & Musitu, 1999), as well as confirmatory factorial analyses (Fuentes et al., 2011; Murgui et al., 2012; Tomás & Oliver, 2004) tested and confirmed its factorial structure based on five different but related dimensions. Additionally, the AF5 scale showed an invariant factorial structure by sex, age, and different languages such as Portuguese (Garcia et al., 2006), Brazilian-Portuguese (Garcia, Martinez, et al., 2018), English (Garcia et al., 2013), and Chinese (Chen et al., 2020). The AF5 has not shown method effects related to its negatively worded items (Garcia et al., 2011; Tomás & Oliver, 2004). The AF5 scale has 30 items (six for each dimension) and a 99-point response scale ranging from 1 = complete disagreement to 99 = complete agreement. Greater scores on AF5 subscales represent a higher self-concept. Cronbach's alphas for the AF5 subscales were: academic subscale = .867, social subscale = .781, emotional subscale = .729, family subscale = .748, and physical subscale = .671.

Data Analyses

A 4 × 2 × 2 multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted for self-esteem and self-concept (academic, social, emotional, family, and physical) with the independent variables being parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful), sex (females vs. males), and age group (adolescents vs. young adults). Follow-up univariate F tests were applied in each source in which multivariate statistically significant differences were found. Statistical results on the univariate tests were also followed up by post hoc comparisons (Bonferroni) among all possible pairs of means.

Results

Parenting Style Groups

The participants were distributed by parenting styles according to their levels of both parental warmth and strictness (see Table 1). The authoritative parenting (M = 68.74, SD = 5.21) and indulgent parenting (M = 68.78, SD = 5.27) styles were associated to higher levels of warmth than the authoritarian parenting (M = 52.32, SD = 8.33) and neglectful parenting (M = 53.08, SD = 6.62). Furthermore, authoritative (M = 38.14, SD = 2.47) and authoritarian parenting (M = 38.76, SD = 3.30) were associated with greater levels of strictness than indulgent (M = 31.56, SD = 3.10) and neglectful parenting (M = 30.94, SD = 3.68).

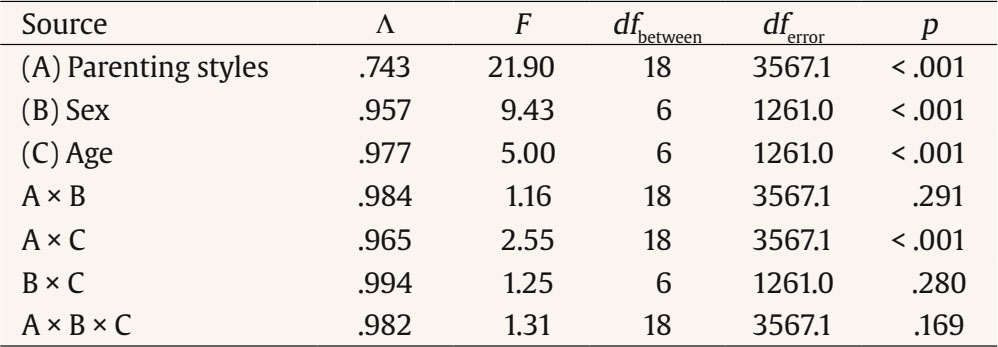

Multivariate Analyses

Differences reached the statistically significant differences for the main effects of parenting style, Λ = .743, F(18, 3567.1) = 21.90, p < .001; sex, Λ = .957, F(6, 1261.0) = 9.43, p < .001; and age, Λ = .977, F(6, 1261.0) = 5.00, p < .001, and for the interaction effects between parenting and age, Λ = .965, F(18, 3567.1) = 2.55, p < .001 (see Table 2).

Sex and Age-related Differences

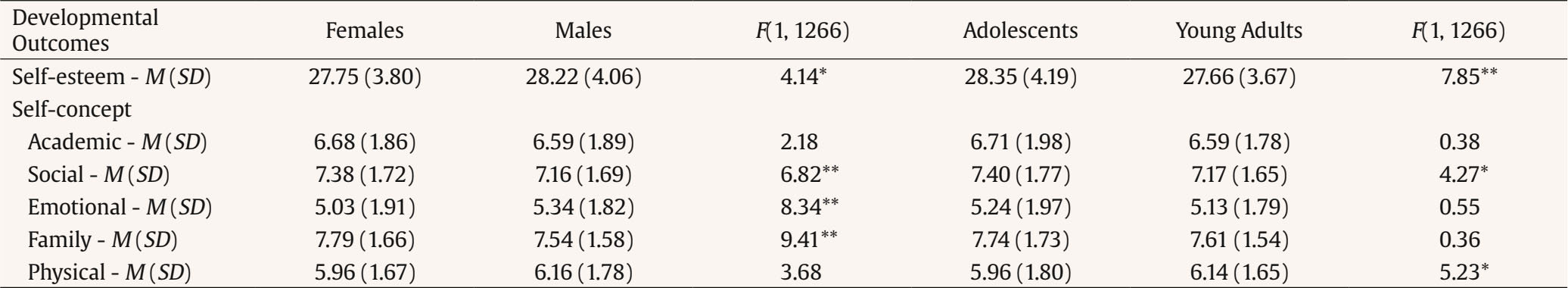

Although not the focus of the study, some sex- and age-related differences reached statistically significant level (see Table 3). Regarding sex-related differences, male individuals reported greater self-esteem than female individuals. On the contrary, female individuals showed greater social and family self-concept, but lower emotional self-concept, than male individuals. Regarding age-related differences, adolescents reported higher self-esteem and social self-concept than young adults, whereas young adults had higher physical self-concept than adolescents.

Parenting Styles

Overall, parenting styles characterized by greater warmth were associated with greater scores on self-esteem and self-concept than parenting without warmth (see Table 4). Additionally, the interaction between parenting style and age was statically significant on self-esteem, F(3, 1266) = 6.61, p < .001, academic self-concept, F(3, 1266) = 5.85, p < .001, emotional self-concept, F(3, 1266) = 3.69, p = .012, and family self-concept, F(3, 1266) = 4.92, p = .002.

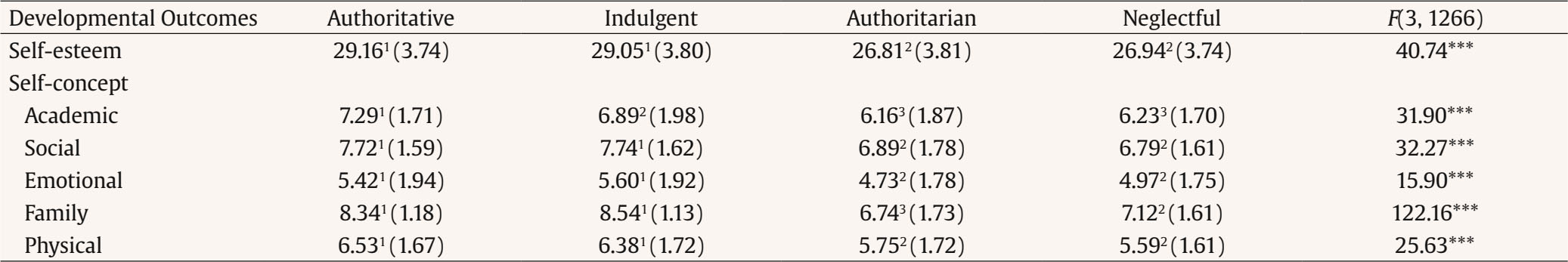

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics Mean and Standard Deviations (in parenthesis) for Parenting Style and Univariate F-values on Developmental Outcomes Based on Self-esteem and Self-Concept

Note. 1 > 2 > 3***p < .001.

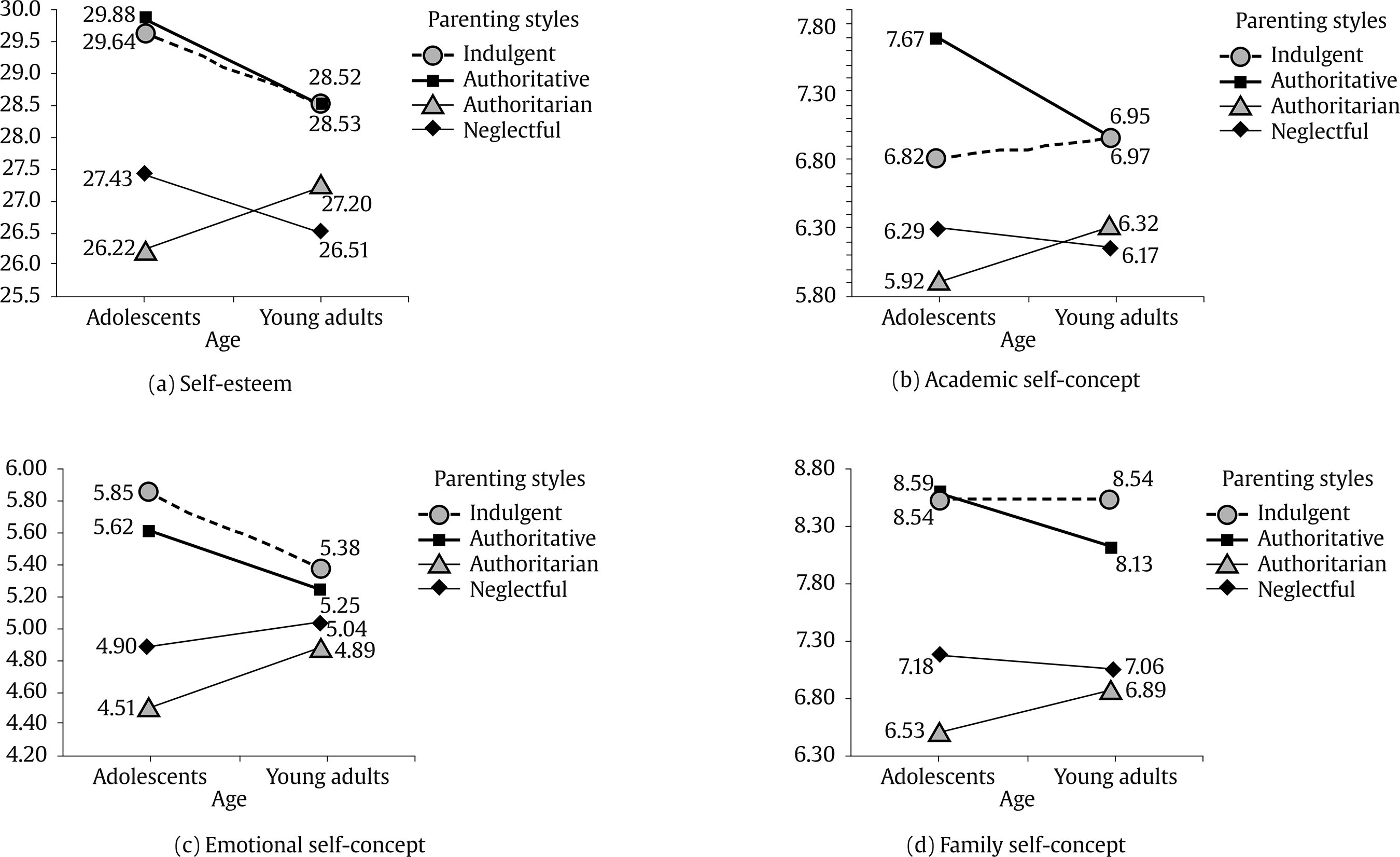

With regard to self-esteem, authoritative and indulgent parenting were related to higher scores in self-esteem than the authoritarian and neglectful styles. The family profile by age revealed higher differences between parenting styles in adolescence than in young adults. Overall, an age-related decrease in self-esteem was found in warm families, but the highest scores for both adolescents and young adults corresponded to those raised in authoritative and indulgent homes (see Figure 1, section A). Parenting characterized by a lack of warmth was related to poor self-esteem. However, the lowest scores among adolescents were associated with authoritarian parenting, while among young adults the lowest scores were associated with neglectful parenting.

Figure 1. Interaction of Parenting Styles by Age. (a) Self-esteem, (b) academic self-concept, (c) emotional self-concept, and (d) family self-concept.

A similar pattern as in self-esteem was found in self-concept dimensions. The highest scores on the academic dimension were associated with the authoritative style, the lowest corresponded to authoritarian and neglectful styles, and the indulgent parenting was in a middle position. The family profile by age revealed an interesting trend among warm families and the authoritative parenting was associated to higher academic self-concept in adolescence, but not in young adulthood (see Figure 1, section B). Fewer scores related to age were found among authoritative families, and it was observed that young adults raised by authoritative parents scored equally as their peers from indulgent homes. Again, poor academic self-concept was related to non-warm parenting in the adolescent and young adult groups.

Individuals with authoritative and indulgent parents reported higher social self-concept than their peers from authoritarian and neglectful families. Regarding emotional self-concept, warm parenting (i.e., authoritative and indulgent styles) was associated with higher scores than non-warm parenting (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful styles). This general pattern was more pronounced among adolescents than in young adults (see Figure 1, section C). Although relatively lower scores related to age were observed among authoritative and indulgent homes (the opposite seems to appear among authoritarian families), young adults raised in warm parenting families also tend to report the highest emotional self-concept.

Differences in family self-concept revealed that individuals with authoritative and indulgent parents scored more positively than their peers from authoritarian and neglectful homes (within non-warmth styles, authoritarian were related to lower scores than neglectful parenting). The family age profile revealed an interesting pattern in adolescence and young adulthood. Adolescents from indulgent homes tend to score more similarly than peers from authoritative homes, whereas young adults tend to report better scores when raised by indulgent parents compared to those from authoritative homes (see Figure 1, section D). Conversely, authoritarian and neglectful parenting were associated with low family self-concept. In adolescence the lowest scores corresponded to the authoritarian parenting whereas in young adulthood both authoritarian and neglectful parenting were associated with the lowest scores. Finally, regarding differences in physical self-concept, authoritative and indulgent parenting were related to higher scores compared to authoritarian and neglectful parenting.

Discussion

The present study examined optimal parenting styles among both adolescents and young adult children from the People's Republic of China. Parenting was examined using the classical theoretical framework based on two dimensions (warmth and strictness) and four parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful) whereas socialization outcomes were examined using self-esteem and self-concept based on five dimensions. The results showed a relatively common pattern in the association of parenting styles with self-esteem and self-concept in China, although with some different nuances in adolescence and young adulthood. Overall, parenting styles characterized by warmth were more beneficial for adolescents and young adults to develop good confidence both in themselves (self-esteem) and in their abilities in different areas required for good personal and social adjustment (self-concept).

Authoritative and indulgent parenting were associated with better scores in self-esteem compared to authoritarian and neglectful parenting. Like self-esteem, parenting styles based on warmth (i.e., authoritative and indulgent) were related to higher self-concept than parenting without warmth (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). The highest academic self-concept corresponded to the authoritative parenting, the lowest to parenting without warmth (authoritarian and neglectful), and the indulgent style was in a middle position. In the social and emotional self-concept, authoritative and indulgent parenting were also related to better scores than authoritarian and neglectful parenting. In family self-concept, the authoritative and indulgent styles were related to high scores, while the authoritarian and neglectful parenting were associated with low scores (the lowest scores correspond to the authoritarian style). Finally, in terms of physical self-concept, individuals raised by authoritative and indulgent parents reported higher scores than their peers from authoritarian and neglectful parents.

Parenting-related differences revealed a relatively common but not equal age-profile among adolescents and young adults in self-esteem and academic, emotional, and family self-concept. Interestingly, the highest academic self-concept was related to the authoritative style, but only in adolescence. Young adults raised by authoritative parents showed the same levels of academic self-concept as their peers from indulgent parents. Also, the differences observed between the highest and lowest scores in self-esteem and academic, emotional, and family self-concept tended to be greater in adolescence compared to young adulthood. However, adolescents and young adults who grew up in indulgent homes scored more optimally than their peers with authoritarian and neglectful parents. Finally, adolescents from authoritarian families had the lowest scores, while young adults raised by authoritarian and neglectful parents obtained similar and the most negative scores, except in self-esteem (the lowest scores corresponded to neglectful parenting).

According to some research with Chinese families conducted in the United States (Chao, 1994, 2001) and the People's Republic of China (Leung et al., 1998; Quoss & Zhao, 1995), the authoritarian style would be effective in favoring healthy development, but the present findings seriously contradict previous evidence. One of the main goals of socialization is for children to become autonomous and independent adults in their society. Self-esteem (i.e., feeling appreciated and as valuable as other members of society) is a socialization outcome (Baumrind, 1978; Rosenberg, 1965). However, according to the present findings, Chinese adolescents and young adults raised by authoritarian parents do not seem to develop confidence in their abilities to function in society. The global evaluation as a valuable person with good qualities (self-esteem) arises from the subjective appraisal in academic and non-academic domains (i.e., multidimensional self-concept) (Esnaola et al., 2023; Marsh & Shavelson, 1985). Interestingly, the present study revealed that negative correlates of authoritarian style in self-esteem seem to extend to self-concept as well.

Academic success is important in any society, but especially in China (Ho, 1986). Influenced by Chinese cultural values, performance in school represents the success (or failure) of the child, but above that it also represents the degree of success of his or her parents because they have the obligation to care for and protect the family (Chao, 2000). According to previous evidence, adolescents would benefit from strict parenting without warmth especially at school (Chao, 2001; Quoss & Zhao, 1995). However, the present study shows that adolescents and young adults raised in strict and non-warm homes (authoritarian) appear to be unsuccessful in school (culturally, their parents are also unsuccessful), at least in terms of valuing their learning qualities (academic self-concept). Therefore, findings from the present study seriously question previous empirical evidence about the benefits of the Chinese authoritarian style especially in terms of school adjustment (Chao, 1994, 2001). But school is only one of the important aspects of the psychosocial adaptation of the individual to society (Marsh & Shavelson, 1985). Non-academic self-concept profiles (social, emotional, family, and physical dimensions) also provide important new evidence on the detrimental consequences associated with the authoritarian style.

Previous studies detect benefits associated with strict but not warm parenting (authoritarian style), whereas parental warmth (i.e., when parents tend to express love verbally, give approval and praise, and be there for children if needed) was associated with behavioral and emotional problems in Chinese adolescents (Xia et al., 2015). It would be expected that the authoritarian style would also be associated with good self-perception in psychosocial adjustment (non-academic dimensions of self-concept) (Leung et al., 1998; Quoss & Zhao, 1995). However, the present study shows that adolescents and young adults raised in authoritarian households rate their abilities to relate to peers and make friends (social self-concept), to regulate emotions in difficult situations (emotional self-concept), and their appearance and physical abilities (physical self-concept) very negatively. Additionally, the findings on the relationship of authoritarian style in another of the non-academic dimensions of self-concept, the family dimension, provide crucial new evidence to the literature.

The data from the present study seriously contradict an idea widely supported to explain some benefits associated with authoritarian parenting: that children raised in authoritarian homes develop a good self-perception of their family (Chao, 1994; Ho, 1986). Some scholars argue that family practices based on discipline and strictness fit very well with the Chinese cultural principle of parental authority and rule and that of obedience and loyalty on the part of children, so that warmth and involvement would be unnecessary, as strict parental guidance could be understood as a sign of love and care (Chao, 2000; Quoss & Zhao, 1995). As some students have pointed out, Chinese children with authoritarian parents would feel loved and appreciated by their family (Chao, 1996). However, according to the present study, adolescents and young adults raised in homes characterized by discipline and strictness, but without involvement and warmth (the authoritarians), do not seem to feel appreciated and valued by their family, at least in terms of family self-concept (they obtained the lowest scores).

On the contrary, the present findings revealed that parenting styles characterized by parental warmth are associated with more positive scores than non-warm parenting styles. The authoritative style seems to be as effective as the indulgent style for self-esteem and non-academic self-concept, and even better than indulgent parenting for academic self-concept (in adolescents, but not in young adults). Some previous emerging studies conducted in China found that the authoritative style was beneficial while the authoritarian style was detrimental (Chen et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2004), but without analyzing the effects associated with the other two parenting styles (i.e., indulgent and neglectful) because they did not classify parenting practices according to the two dimensions of the model (i.e., warmth and strictness) that defines the four parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful). However, parenting research based on the two-dimensional theoretical model with four parenting styles, which has been widely tested in Western societies (e.g., Europe and United States) (Calafat et al., 2014; Lamborn et al., 1991), has been little used in Eastern societies, such as China. Therefore, the present study extends the study of parenting based on the two-dimensional model with four parenting styles from the Western to the Eastern societies making it possible to detect the positive parenting style across the world with the same theoretical framework (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Garcia et al., 2019; Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Martinez & Garcia, 2007; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). The present study revealed differences in self-concept and self-esteem not only between the two parenting styles characterized by strictness (authoritarian and authoritative) but also between the four parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful).

In the ancient Chinese society, and perhaps when there is a risk of acculturation and loss of identity (Chinese families in foreign countries), hierarchical relationships based on ruling and teaching (by parents) and obedience and loyalty (by children) can guide children and strongly bond family members, which may explain the developmental benefits identified in classical studies (Ho, 1986). By contrast, in contemporary China there seems to be an evolution of the role of parents from traditional forms based on hierarchy and order to more egalitarian relationships between parents and children, although families today continue to be strongly influenced by collectivism (Xia et al., 2015). In this sense, it is possible that the optimal parenting style could be affected by contemporary Chinese culture. Parental warmth (common to indulgent and authoritative parenting) seems to be beneficial for positive development, probably because of more egalitarian relationships among family members, whereas strictness seems to be unnecessary (in terms of self-esteem and non-academic self-concept), except for academic self-concept (but only in adolescence, not in young adulthood). The results of the present study partially coincide with other previous emerging research focused on parenting practices and their consequences on the emotional and academic development of Chinese adolescents: warm practices were positively related to emotional and academic development, while strict practices were also beneficial but only for academic development (Wang et al., 2007).

Although perhaps to a lesser extent than before, academic achievement is still highly valued socially in contemporary China and therefore seems to affect not only children, but the family as a whole (especially the parents). Chinese adolescents may succeed in secondary and high school and pursue university studies (being the pride of their family), but also fail in their academic goals (bringing shame on the family) (Li, 2020). The greatest benefits of authoritative compared to indulgent parenting were found in the adolescent group (but not in young adults) in academic self-concept, an important indicator of academic adjustment, probably because in the Chinese society school adjustment is one of the most socially valued areas of psychosocial adjustment. The present results suggest that higher academic outcomes (e.g., academic self-concept) may require parental strictness but in combination with warmth (i.e., authoritative parenting), especially in adolescence which is a period of higher vulnerability and difficulties. By contrast, in the young adult group (once socialization is complete), those who were raised in authoritative households (warmth and strictness) scored equally as their peers from indulgent homes (warmth without strictness), which seems to suggest that the benefits of strictness might be especially good in adolescence, but unnecessary once parental socialization is over (adulthood). It is possible that for young adults, who are not under the supervision and care of parents and are more mature than in adolescence, the greatest benefits related to academic outcomes (e.g., self-concept) could be related to parental warmth regardless of strictness (i.e., authoritative and indulgent).

Although not the central focus, sex- and age-related differences were found. Adolescents scored higher than young adults on self-esteem and social self-concept, but lower on physical self-concept. Additionally, male individuals reported higher self-esteem than female individuals. In terms of self-concept, female individuals had higher social and family self-concept than male individuals, whereas male individuals scored higher than female individuals in emotional self-concept. Sex-and age-related differences in self-esteem and self-concept do not seem to be the same as in Eastern countries, but the main effects of sex and age align with previous research conducted in China (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2020).

The present study extends the analysis of differences in socialization outcomes as a function of parenting styles based on warmth and strictness to China, although some cautions should be noted. We cannot determine a causal relationship between parenting and socialization outcomes (self-esteem and self-concept) because the methodology is not experimental. However, differences in self-esteem and self-concept related to parenting styles have a similar pattern (main benefits related to parental warmth) to that of studies conducted in the United States and Europe. In addition, the present study examines parenting during adolescence and beyond (among young adults, once parental socialization has ended) based on a cross-sectional rather than longitudinal design. Although we cannot draw conclusions about the evolution of self-esteem and self-concept throughout adolescence among the individuals of the four households (i.e., authoritarian, authoritative, indulgent, and neglectful), the strategy followed in the present study is often used in research with adult children. Therefore, findings based on a cross-sectional design are preliminary and should be confirmed in longitudinal studies. In addition, the respondents were adolescents and young adults rather than their parents, but some evidence highlights that children are more reliable than parents.

Optimal parenting has been examined for decades. The two-dimensional theoretical model, widely used in Western societies (e.g., United States and Europe), considers the combined effects of warmth and strictness, but has been scarcely used in Eastern societies, especially in China. Contrary to some evidence on the benefits of strictness without parental warmth, especially for academic performance, the present results showed the poor results in self-esteem, non-academic self-concept (social, emotional, family, and physical) and academic self-concept associated with the authoritarian style. Future studies should continue to examine optimal parenting worldwide and, particularly, in China, based on the two-dimensional theoretical model (Maccoby & Martin, 1983) to identify if positive parenting is based on strictness without warmth (the authoritarian style or first stage), strictness with warmth (the authoritative style or second stage), or warmth without strictness (the indulgent style or third stage) (Garcia et al., 2019). The results of the present study provide clear evidence of differences in self-concept and self-esteem in China depending on parenting styles. Although broad benefits of warmth without strictness in self-esteem and non-academic self-concept are observed (indulgent parenting), optimal parental socialization in China seems to be based on warmth and strictness (authoritative parenting or second stage), especially for academic success but only during adolescence (in terms of academic self-concept). Future studies should examine Chinese parenting styles in adolescence and beyond with longitudinal studies to identify optimal parenting in broad indicators of psychosocial development, particularly academic adjustment.