INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis, a condition commonly associated with advanced age, is characterized by a reduction in bone mass density and a concomitant deterioration of bone microstructural integrity, leading to an increased susceptibility to fractures (1). The overall prevalence of osteoporosis results in more than 10 million fragility fractures annually, a number that is expected to rise in the coming years due to the aging global population (2). Importantly, osteoporosis-related fragility fractures linked are associated with a significant reduction in quality of life and increased disability.

Currently, there are 2 different approaches to manage osteoporosis: antiresorptive and osteoanabolic drugs. Antiresorptive agents block the osteoclast-mediated bone resorption process. Typical antiresorptive agents are monoclonal antibodies such as Denosumab—targeting RANKL—an activator of pre-osteoclast maturation or bisphosphonates such as alendronate, which induce osteoclast apoptosis. On the other hand, drugs such as teriparatide, a truncated PTH derivative (3), or abaloparatide, a PTH analog (4) have an osteoanabolic function, stimulating osteoblasts proliferation. Both antiresorptive and osteoanabolic drugs have important adverse effects associated to prolonged used, something difficult to avoid in a chronic disease such as osteoporosis (3,5). No new agents had come to market in the last few years except for romosozumab, an anti-sclerostin antibody with a dual antiresorptive and osteoanabolic action (6). However, although treatment with romosozumab dramatically reduces the occurrence of fragility fractures in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis (7), clinical trials showed an increased cardiovascular risk in patients on romosozumab (7). In addition, the cost of treatment per patient with romosozumab is significantly higher than that of other anti-osteoporotic drugs, something that would negatively impact the national health system. Hence, an emergency clinical need exists to develop cost-effective and long-term safe osteoporosis treatments.

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in using mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)-based approaches to improve bone regeneration (8). MSCs are multipotent cells with self-renewal capacity, which makes them promising candidates for therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine (9). Importantly, MSCs from osteoporotic individuals seem to have an increased adipogenic capacity at the expense of their osteogenic potential. Therefore, we hypothesize that the enhancement of this osteogenic capacity in MSCs would be a valid approach for osteoporosis treatment. We propose to increase this osteogenic potential of MSCs by silencing key genes with anti-osteogenic activities.

The Wnt/β-catenin (10) and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) signaling (11) pathways play major roles in bone formation. The activation of these pathways drives the transcription of genes, such us alkaline phosphatase (ALPL), osteocalcin (BGLAP) and the Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), which regulate osteoblast differentiation, extracellular matrix synthesis, and bone mineralization. Previous works from our group have shown that silencing inhibitors of the BMP (Smurf1) or the Wnt/b-catenin (Sfrp1) pathways lead to a significant increase in the osteogenic capacity of MSCs in vitro in MSCs from osteoporotic patients (12,13). Moreover, we designed a system to specifically silence those genes at the endogenous MSCs (14). Our system is based on the use of a particular type of lock nucleic acid-antisense oligonucleotides (LNA-ASOs), known as GapmeRs. These molecules consist of a single-stranded deoxyribonucleotide typically composed by 14-20 bp, which specifically binds to its mRNA target creating a DNA/RNA hybrid duplex that will be then recognized by the RNAseH leading to the degradation of the targeted mRNA (15). The GapmeR construct includes a central DNA sequence flanked by 2 RNA sequences modified for heightened resistance to endonucleases, ensuring optimal efficacy and durability (13). The silencing produced by the GapmeRs is transient and does not cause permanent changes to the DNA, thus reducing possible unwanted side effects. This method is clinically safe enabling the translation of this treatment into the routine clinical practice (16). In fact, some treatments currently used in clinical practice are based in the use of ASOs (17), such as eteplirsen for treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) (18), or nusinersen for treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (19). To specifically deliver the GapmeRs to endogenous MSCs, these molecules are encapsulated within hybrid nanoparticles and specifically directed to the BM-MSCs using aptamers that recognize these cells. We have shown that silencing Sfrp1 in vivo, at the level of the endogenous MSCs, using this system is a viable approach to increase bone mass in an osteoporotic mouse model. Targeting this inhibitor of the Wnt/b-catenin in vivo using this gapmeR-nanoparticles-aptamer system increases bone mass in osteoporotic mice by up to 30 % (12,14). Our current aim is to increase bone-formation efficiency of our system. For this purpose, in this work we tested the feasibility of targeting another signaling pathway that has an anti-osteogenic activity, the NF-kB pathway, with the notion that the simultaneous silencing of Sfrp1 and a putative target from the NF-kB pathway will significantly increase the previous percentage.

The NF-kB signaling pathway includes 3 integral components: the NF-kB dimer, the IKK complex, and the IκB protein (15). Although the NF-kB dimer is constitutively present in the cytosol of cells it is kept in an inactive state by the action of the IkB proteins. IkB proteins have a domain called the destruction box, which is rich in serine residues. When the cell receives a signal activating the NF-kB pathway, serine residues in the destruction box domain are phosphorylated by the IKK protein kinases, thus inducing the degradation of the IkB protein and the release of the NF-kB dimer. Once released, this dimer can translocate to the nucleus and regulate the expression of target genes (15). The NF-kB pathway exhibits 2 distinct modalities known as the canonical and alternative pathways. In the canonical route, the IKK complex is composed by Ikkα, Ikkβ, and Nemo. Ikkβ serves as the primary kinase responsible for phosphorylating the serine residues within the IkBα destruction box. The phosphorylation of IkBα leads to the release of the NF-kβ dimer, which translocates into the nucleus (15). In contrast, the non-canonical or alternative route depends on Nik, which is a constitutively active but normally degraded protein. When the cell receives an activation signal from the NF-kB pathway, the degradation of Nik stops and Nik phosphorylates the Ikkα protein, thus leading to a subsequent release of the NF-kB dimer, which again translocates into the nucleus (15). The NF-kB canonical and no canonical pathways are involved in many processes, such as cell proliferation and survival, DNA damage repair, and immunity (20). NF-kB inactivation has been associated with an increased osteoblast activity and bone formation (21) suggesting that inactivation of this pathway could be a likely approach for further enhancing bone formation in our model (22).

The NF-kB signalling pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating various basic cellular functions, including viability, migration, chemotaxis, and proliferation, particularly in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). NF-kB is a family of transcription factors that control the expression of genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses, as well as cell survival, differentiation, and apoptosis (23). In MSCs, NF-kB activation is crucial for maintaining cellular viability by regulating anti-apoptotic genes and promoting resistance to stress-induced cell death. Moreover, NF-kB influences the migratory and chemotactic capabilities of MSCs, which are essential for their therapeutic potential in tissue repair and regeneration. This pathway modulates the expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules, thereby guiding MSCs migration towards injury sites (24). NF-kB also plays a significant role in cell proliferation by regulating the expression of cyclins and other cell cycle-related proteins, ensuring proper cell cycle progression and proliferation. These multifaceted roles underscore the importance of NF-κB signalling in the functional regulation of MSCs and its potential implications in clinical applications. Besides its implication in bone formation and basic cellular functions, the NF-kB pathway plays a crucial role in the regulation of inflammation, which indirectly impacts bone formation. Ageing and, in women, the decline in estrogen levels after menopause, lead to a significant increase of inflammation in the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment, resulting in the establishment of a hostile environment. This inflammatory environment prevents the differentiation of MSCs into osteoblasts promoting their adipocytic differentiation (25). The activation of the NF-kB pathway in BM MSCs directly contributes to the establishment of this hostile microenvironment. Once this pathway has been activated in MSCs, these cells would produce a set of pro-inflammatory cytokines, that, in turn, exacerbate inflammation, further hindering bone regeneration.

We propose that silencing key genes of the canonical and/or non-canonical NF-kB pathways in MSCs would increase their osteogenic capacity, thus increasing the efficiency of our previous model based on the sole silencing of Sfrp1. Importantly, this approach would not only enhance osteogenic differentiation but could also modulate the composition of the MSCs secretome, thus reducing the presence of pro-inflammatory factors. This immunomodulatory effect would create a permissive BM microenvironment that would facilitate bone regeneration. Both strategies aim to effectively increase bone mass, offering a promising treatment approach for diseases characterized by reduced bone mass, including osteoporosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CELL CULTURE

C3H10T1/2 (Clone 8, Ref. CCL-226, ATCC, Manassas, VA, United States), an immortalized murine MSCs line was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10 % Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin. Cell passage was performed using TrypLE Express (Ref. 12604-013, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA United States).

GapmeR DESING

Antisense LNA GapmeRs were purchased from Exiqon (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). A non-specific GapmeR Negative Control A (Ref. 339515 LG00000002-DDA) was used as a control GapmeR, and specific GapmeRs were used to target Ikkα (Ref. LG00824583-DDA), IKKβ (Ref. LG00824663-DDA), Nemo (Ref. LG00824633) and Nik (Ref. LG00824353).

CELL TRANSFECTION

Lipofection was performed in a 24-well plate using Dharmafect (Ref. T-2001-01, Dharmacon, Horizon Discovery, Cambridge, United Kingdom), following the manufacturer's instructions for use. Cells were seeded at 12,500 cells/cm2 24 hours before transfection. Two hours before transfection, cells were washed twice with PBS 1X and culture medium was replaced with Opti-MEM (Ref. 31985047, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Walthman, MA, United States). GapmeR concentration used was 20nM. Transfection was performed following the manufacturer's instructions for use. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 hours, an equal volume of culture medium was added. Finally, 48 hours after transfection, the medium was removed and the cells were washed once with PBS, and culture medium was added.

RNA EXTRACTION AND CONVERSION TO CDNA

Cells were washed twice with PBS prior to collect the mRNA using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Walthman, MA, United States). After TRIzol addition, the plate surface was scrapped to maximize the material collected. RNA was extracted following the manufacturer's instructions for use. mRNA retrotranscription was performed with the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (RR037A, Takara Bio Inc, Shiga, Japan) following the manufacturer's instructions for use. The resulting cDNA was diluted 4 times with ddH2O to perform gene expression analysis by semi-quantitative PCR.

GENE EXPRESSION ANALYSIS

Gene expression levels were measured using semi-quantitative PCRs TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, United States). To test gene silencing, the following TaqMan assays were used: Mm00432529_m1 (Ikkα), Mm01222247_m1 (Ikkβ), Mm00494927_m1 (Nemo), Mm00444166_m1 (Nik). To analyze gene expression of the NF-kβ pathway target genes, the following TaqMan assays were used: Mm00446190_m1 (Il-6) and NFkB1A (Mm00477798_m1). For normalization, we used the mouse housekeeping GAPDH gene (Assay Mm99999-915_G1).

FLOW CYTOMETRY AND APOPTOSIS ASSAY

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (556547, BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, United States) was used following the manufacturer's instructions for use. Forty-eight hours after transfection, 100,000 cells per condition were transferred into 2 flow cytometry tubes and washed twice with 1× PBS at 4 °C. The cells were, then, resuspended in 100 µL of Binding Buffer and 2.5 µL of Annexin V-FITC labelled antibody was added to 1 tube for each condition. After 30 minutes incubation in the dark, cells were washed twice with 1X PBS at 4 °C and resuspended in 100 µL of Binding Buffer. Finally, 2.5 µL of 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) was added to each tube just before flow cytometry.

CELL PROLIFERATION ASSAY

Cells were transfected in 24-well plates as previously explained and harvested 48 h after transfection. Afterwards, different cell numbers (100, 200, 300 and 400 cells per well) were seeded onto a 96-well plate in triplicates and allowed to attach overnight. Then, cells were allowed to proliferate for 1, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 days. To determinate cells viability at different timeframes, culture media was substituted by complete DMEM (10 % FBS and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin) containing 0.5 mg/mL of 3-(4.5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and cells were incubated for 4 hours. Then, the media was changed to 100 µL of 2-propanol and incubated at 37ºC for 10 minutes. Finally, absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a plate lector Eon (BioTek, Winooski, VT, United States). The results are represented as the increase in cell number vs the previous day.

CELL MIGRATION ASSAY

Cell migration capacity after transfection with the GapmeRs was analyzed by a wound healing assay. For this, C3H10T1/2 cells were seeded at high confluence in a 6-well plate (25,000 cells/cm2) and then transfected following the standard protocol. Wounds were performed using a 0.1-20 µL pipette tip to produce wounds 300 µm wide. In a Nikon Eclipse Ti (Nikon Instruments Inc. Melville, NY, United States), pictures of the 6 different fields were taken every 3 hours for a total of 15 hours. The live cell microscope maintained the cells at 37 °C under normoxic conditions. Finally, we measured the area of the wound every 3 hours with the NIS-Elements software (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, United States), and determine the average wound area per time and condition.

TRANSWELL MIGRATION ASSAY

A total of 7000 transfected cells resuspended in 200 µL of serum-free media were seeded per upper chamber of a 6.5 mm Transwell with 8 µm Pore Polycarbonate Membrane Insert (3422, Corning, Somerville, Massachusetts, United States). Cells were incubated with 100 ng/mL Stromal cell-Derived Factor-1 (SDF-1, Ref. 10118-HNAE, Sino Biological Inc., Houston, Texas, United States) in 600 µL of serum-free media in the lower chamber for 24 hours at 37 °C. After incubation, to avoid background signal, cells that did not migrate through the membrane were eliminated by washing the upper chamber twice with 1× PBS and cleaning it with a cotton swap. Finally, cells were stained with 600 µL 1.01 µg/mL DAPI (Ref. 62248, ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockforf, United States) in 1X PBS for 10 minutes and kept in 1× PBS until 4-5 fields per well at 10× pictures were taken in a fluorescence or phase contrast microscope. Graph represents average cell number per well.

RESULTS

NF-KB PATHWAY INACTIVATION IN THE MSCS CELL LINE C3H10T1/2

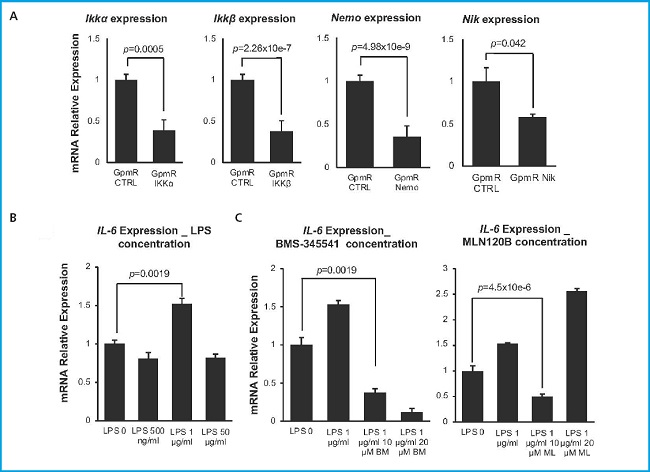

We hypothesized that silencing key genes in the NF-kB pathway may led to a reduced overall activity of the pathway, thus increasing the osteogenic potential of MSCs. To put this hypothesis to the test, we first needed to efficiently silence these genes and confirm the inactivation of the pathway in the murine MSCs cell line C3H10T1/2. We selected 4 key components of the canonical and non-canonical pathways: Ikkα, Ikkβ, Nemo and Nik and designed specific GapmeRs to achieve gene silencing. The expression of the targeted genes was assessed by qPCR 48 hours after transfection with these GapmeRs (Fig. 1A). Transfection with a non-specific gapmeR was used as a control in all the experiments (GpmR Ctrl). We observed a statistically significant silencing of 61.2 % of Ikkα, 62.1 %of Ikkβ, 64.5 % of Nemo and 43 % of Nik vs control.

Figure 1. Silencing of NF-kβ pathway in the C3H10T1/2. A. Relative expression of targeted genes. Expression was measured 48 hours after transfection with specific GapmeRs. Absolute values were normalized vs those obtained after transfection with a control GapmeR (n = 4). B. Relative expression of Il-6 after treatment with different concentrations of LPS. Expression was measured 18 hours after growing C3H10T1/2 with LPS 0.5, 1 and 50 μg/mL to activate NFkβ pathway (n = 3). C. Relative expression of Il-6 with commercial inhibitors BMS-345541 and MLN120B in the presence of 1 μg/ml LPS (n = 3). Bars show standard deviation of mean values.

Once we confirmed the silencing of the different targets, we needed to make sure that those levels of silencing led to a significant inhibition of the NF-kB pathway. For this purpose, we needed to establish a method to monitor the activation of the NF-kB signaling pathway. Activation of this pathway in MSCs in vitro is generally achieved through incubation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (26). To determine the optimal concentration of LPS for pathway activation in our experimental settings, we measured the activation of the pathway in response to different concentrations of LPS by evaluating the increase in Il-6 expression levels, a direct target of this pathway (27). We conducted a screening in untransfected cells using 3 different concentrations of LPS (0.5 µg/mL, 1 µg/mL, and 50 µg/mL) (Fig. 1B). Our results indicate that a concentration of 1 µg/mL LPS leads to a significant increase in Il-6 expression levels and thus, is optimal for NF-kβ pathway activation. This amount of LPS, maintained in the culture media for 18 hours, resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in Il-6 expression.

Simultaneously, we determined the appropriate concentration of commercial inhibitors of the NF-kB pathway (BMS-345541 and MLN120B) that effectively block its activation without inducing toxicity in the C3H10T1/2 cell line (Fig. 1C). These molecules would be used as controls of pathway inhibition in our experiments. Two different concentrations of each inhibitor were tested, 10 µM and 20 µM in cells cultured in the presence of 1 mg/mL LPS. With both inhibitors a concentration of 10 µM was found to significantly inhibit the surge in Il-6 expression in response to LPS. In the case of the BMS-345541 inhibitor, a higher reduction in Il-6 expression was detected when the concentration used was 20 µM due to the toxic effect of this condition that would lead to a significant increase in cell death.

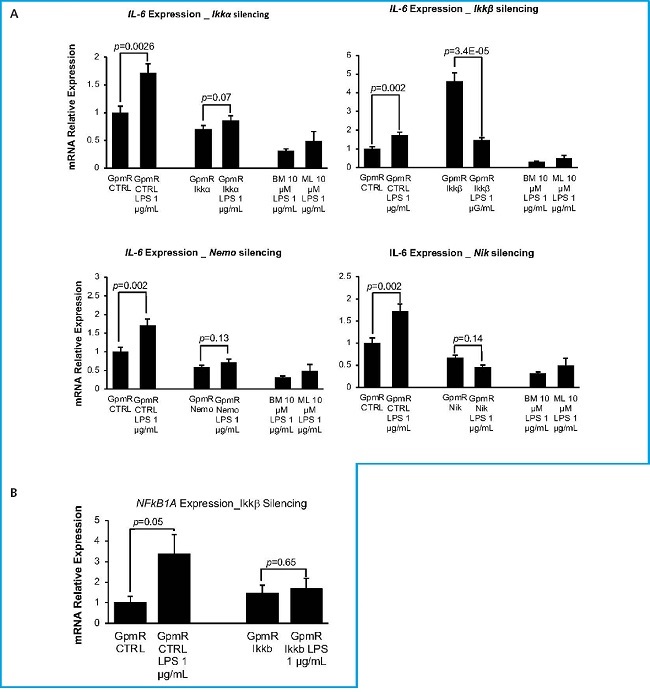

Once the appropriate concentrations of LPS and inhibitors were determined, we were set to verify that the inhibition of the different components of the NF-kB pathway with the specific GapmeRs did indeed lead to a reduction in the activity of the pathway. Therefore, we compared the expression of Il-6 in transfected cells grown in LPS to that of cells transfected with the control GapmeR grown in the same inductive conditions. The decrease in the level of pathway activity achieved by the silencing of each of the genes was compared to that achieved by the commercial inhibitors BMS-345541 and MLN120B (Fig. 2A). The results show that cells transfected with Ikkα, Nemo and Nik GapmeRs did not respond to LPS by increasing Il-6 expression confirming that the silencing of those genes greatly impacts the activity of the pathway. Results obtained with cells where IKKβ had been silenced where somewhat different. The graph shows that Il-6 expression significantly increases in cells where Ikkβ has been silenced vs the gpmR control group without LPS. Since it has been described that Ikkβ silencing could have an effect on the expression of negative regulators of the pathway, such as IkBa, which sequester NF-κB in the cytoplasm, affecting both basal and stimulated activity, we decided to analyze the expression of an alternative target of the NF-κB pathway, the NFkB1A (28) gene (Fig. 2B) to provide insights into whether the observed effects on Il-6 are specific to its regulatory mechanisms or reflect a broader alteration in NF-kB signaling. In this case, the pattern of NFkB1A, unlike Il-6, would support the negative effect of Ikkβ silencing on general NF-kB activity.

Figure 2. Relative Expression of Il-6 in silenced cells treated with LPS. Expression of Il-6 (A) or NFkB1A (B) measured 48 hours after transfection with specific GapmeRs. Representative experiment. Cells transfected with control GapmeR (GpmR Ctrl) or GapmeRs-specific for the silencing of target genes (GpmR IKKα, GpmR IKKβ, GpmR Nemo, GpmR Nik) were grown in the absence (LPS 0) or presence (LPS 1 mg/mL) of lipopolysaccharide and different inhibitors of the NF-κβ signaling pathway (BM and ML) used at a 10mM concentration. BM stands for inhibitor BMS-345541 and ML stands for inhibitor MLN120B. Graph shows values from a representative experiment. Bars show standard deviation of mean values.

EVALUATION OF THE BIOSAFETY OF SILENCING NF-KB GENES IN THE MURINE MSCS CELL LINE C3H10T1/2

Since the NF-kB pathway regulates various cellular responses, including cell proliferation, migration, and survival, we decided to analyze the effect of Ikkα, Ikkβ, Nemo and Nik silencing these basic cellular functions.

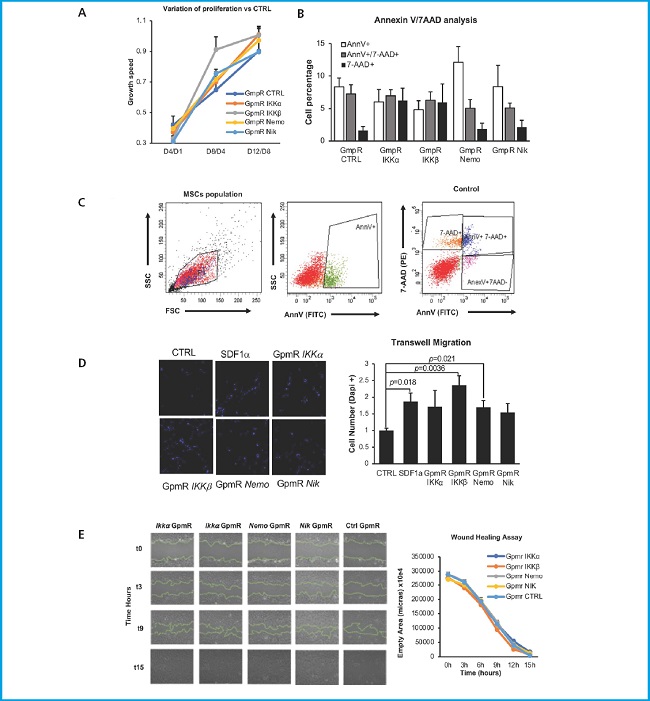

To analyze the proliferation of the transfected cells, we performed an MTT assay (Fig. 3A). Results are represented as the increase in cell number vs the previous day. No significant differences were observed between the silenced cells and control, except for Ikkβ silenced cells at the D8/D4 point exhibiting a significant increase in proliferation. Nevertheless, this increase was resolved at the last day, a point at which proliferation levels were comparable to those of the control.

Figure 3. Evaluation of the biosafety of MSCs C3H10T1/2 cell line expressing low levels of NF-κβ key genes. A. Effect of target inhibition on cell proliferation. Results from the MTT analysis to measure the effect of target gene inhibition on cell proliferation ability. The results are expressed as the difference of each endpoint relative to the previous one (n = 2). B. Effect of target inhibition over the response to chemotactic agents. C3H10T1/2 migration capacity in response to SDF-1α. To the left, representative images of transfected cells that migrated through the transwell membrane stained with DAPI (magnification 10×). To the right, quantification of migrating cells. The number of migrating cells in each case is normalized vs the number of cells transfected with the control GpmR migrating in the absence of SDF-1α. Representative result (n = 5). C. Effect of target genes inhibition over MSCs viability. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells marked with AnnV and/or 7-AAD. AnnV+ are early apoptotic cells, AnnV+/7-AAD+ are late apoptotic cells, and 7-AAD+ are necrotic cells (n = 3). For all experiments, graph express the mean values of 5 or 3 experiments, as indicated. Bars show standard deviation of the mean values.

CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling is involved in the chemotaxis and homing of stem cells (29). Since one of the known targets of the NF-kB pathway in other cells is C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) (30), the receptor for the stromal cell derived factor 1 (SDF-1 α) (27), we decided to analyze if silencing the different genes could affect the capacity of transfected cells to respond to this chemotactic agent (Fig. 3B). Therefore, we performed a chemotaxis analysis using a transwell migration assay. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were added to the upper side of a 0.8 transwell membrane and exposed to medium containing SDF-1 on the lower chamber of the transwell. Cells were allowed to migrate towards the lower part of the transwell membrane for 24 hours. Cells that had migrated and were attached to the lower part of the transwell membrane were stained with DAPI and detected using fluorescence microscopy. The results are normalized to gapmeR control-transfected cells exposed to SDF-1. The negative control (CTRL corresponding to cells not exposed to SDF-1α) showed a significantly lower migration than that of cells exposed to SDF-1α (SDF-1α). However, no significant differences were found between the chemotactic response to SDF-1α of the cells where the different genes of the NF-kB pathway have been silenced and non-transfected cells.

Finally, to analyze the effect of Ikkα, Ikkβ, Nemo and Nik silencing on MSCs viability, we performed an Annexin/7-AAD assay (Fig. 3C) 48 hours after transfection, using annexin V (AnnV) and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD). AnnV marks cells undergoing apoptosis, as it binds to phosphatidylserine when this phospholipid translocates to the outer part of the cell membrane, one of the early signs of apoptosis. Conversely, 7-AAD marks cells in late apoptosis, as it binds to DNA but cannot penetrate intact cell membranes, thus only entering the cells when cellular integrity is compromised. We can detect viable cells (Ann-/7-AAD-), early apoptotic cells (Ann+/7-AAD-), late apoptotic cells (Ann+/7-AAD+), and dead cells (Ann-/7-AAD+). Although a tendency to an increase of apoptotic cells was observed upon transfection with the gapmeR for the Nemo silencing, this difference was no significant, suggesting that the silencing of genes from the NF-kB signaling pathway has no effect on cell viability.

DISCUSSION

MSCs-based approaches had been proposed as an alternative to improve bone regeneration. We have previously managed a 30 % increase in the osteogenic potential of osteoporotic MSCs by silencing Sfrp1, an inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (14). We hypothesize that it would be possible to further increase this osteogenic potential by silencing key genes of the NF-kB canonical and non-canonical pathways. This hypothesis originates from the previously explained role of the pathway in reducing bone mass, both directly through the inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and indirectly through the increase of inflammation levels in the BM microenvironment.

Regarding its anti-osteogenic activity, the NF-kB signaling pathway influences osteogenesis through different mechanism. NF-kB binds to the promoter of Smurf1 and Smurf2, both inhibitors or the BMP pathway, and increases their transcription (22). In addition, NF-kB inhibits the activity of Fos-related antigen 1 (Fra-1) (31). This protein, part of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) family, regulates the expression of various genes involved in osteoblast differentiation and bone matrix production. In relation to the indirect influence of NF-kB in bone formation, this pathway plays a major role in establishing the BM pro-inflammatory microenvironment. Loss of estrogen increases the activity of Th17 (32) cells, and, consequently, proinflammatory cytokines such as Interleukine-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukine-17 (IL-17) and receptor activator of NF-kβ (RANKL) (33). These molecules work by activating the NF-kβ signaling pathway, thus perpetuating the activation of Th17 lymphocytes by producing cell survival factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, the activation of the NF-kβ pathway inhibits the anti-inflammatory activity of B lymphocytes. B cells reduce the pro-inflammatory environment and increase bone formation producing osteoprotegerin (OPG) (33), while T cells have a pro-inflammatory action (34). These pro-inflammatory cytokines also inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by increasing the expression of sclerostin and decreasing the synthesis of RUNX2, IBSP and BGLAP (35). All this combined results in major differentiation of MSCs into adipocytes, decreasing their differentiation into osteoblasts, thereby compromising bone homeostasis.

To silence the selected target genes of the NF-kB pathway we designed a specific gapmeR for each target gene which binds to the mRNA molecule by inducing its degradation by the RNase H. The silencing caused by this system is transient and does not cause permanent changes to the DNA, thereby ensuring its safety. Silencing target genes with GapmeRs was confirmed by qPCR. The expression of target genes is significantly reduced after transfection vs the control GapmeRs, indicating an efficient silencing of those genes. Although the different expression of the targeted genes between control cells and those transfected with the correspondent GapmeR were rarely > 65 %, this reduction in gene expression is enough to produce substantial changes in cellular behavior, protein production, and overall phenotype. For instance, in therapeutic contexts, even the partial knockdown of a gene involved in a disease can result in meaningful clinical improvements (36,37).

Once the efficiency of GapmeRs in silencing gene expression was evaluated, we needed to perform an essay to make sure that the inhibition of target genes effectively reduced NF-kB signaling. IL-6 serves as a marker of pro-inflammatory activity, showing clear responses to pathway activation levels (27). Ikkα, Ikkβ, Nemo and Nik targeting showed a statistically significant reduction of Il-6 expression upon activation with LPS 1 µg/mL for 18 hours vs control (Fig. 2A), meaning that NF-kB is effectively inhibited even in the presence of an inducer. This underscores the fact that a small percentage of gene silencing could have substantial effects on cell phenotype, particularly in the case of Nik silencing where a significant decrease of Il-6 expression is achieved. Interestingly, we found that cells where Ikkβ had been silenced showed a significant increase in Il-6 expression without LPS. However, expression levels of NFKBIA—another direct target of the NF-kB pathway—did follow the expected expression pattern and were downregulated in Ikkβ-silenced cells. The differences in the effects of Ikkβ silencing on Il-6 and NFkBIA (IκBα) expression highlight the complex nature of NF-kB signaling regulation. When Ikkβ is silenced, the canonical NF-kB pathway is inhibited, as evidenced by the decreased expression of NFKBIA. However, the increased Il-6 expression could be due to compensatory mechanisms such as the activation of the MAPK/ERK or JNK pathways, which can independently regulate IL-6 production (38). Moreover, the NF-κB pathway involves intricate feedback loops, and silencing IKKβ might disrupt these loops, leading to an unexpected upregulation of Il-6 as a compensatory response (39).

NF-kB pathway is not only involved in inflammation but in other cell functions such as cell proliferation. Therefore, we needed to make sure that the changes introduced in the MSCs did not affect basic cell functions. Although the results of our MTT assays showed a significant difference in Ikkβ-silenced cells at the midpoint. Of note, this difference disappears at the endpoint when its proliferation matches the control. This suggests that this difference found at midpoint is not due to a true increase in their proliferation capacity. No other significant differences were found. Therefore, these results suggest that the silencing target genes does not affect the cells proliferative capabilities.

On the other hand, reducing NF-kB pathway activity by silencing target genes could reduce CXCR4 expression affecting the MSCs behavior in the bone marrow. However, the results of our transwell migration assay eliminated this possibility in our system since no statistically significant differences were found between the different conditions. These results suggest that NF-kB silencing is not affecting the ability of the transfected cells to respond to chemotactic agents. In fact, MSC chemotaxis could be regulated by other signaling pathways that are not affected by the silencing of NF-kB components. For instance, chemokine receptors such as CXCR4 are also regulated by the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signalling pathways, which might maintain chemotactic responses independently of NF-kB (40).

To be able to use a pro-regenerative approach involving silencing of any of the targeted genes in vivo, we also needed to guarantee the safety of this change and check that silencing of the targeted genes was not touching the cells viability. Therefore, we conducted a flow cytometry analysis with AnnV and 7-AAD. Our results show no significant differences at this level between control and the silenced cells. However, Nemo-silenced cells seem to have more apoptotic cells, and Ikkα and Ikkβ-silenced cells seem to have more percentage of necrotic cells. However, none of these differences were significant confirming that silencing targeted genes does not affect the cells viability.

Our study demonstrates that targeted silencing of key genes in the NF-kB pathway could be used as an approach to enhance the osteogenic potential of MSCs without compromising their viability, proliferative capabilities, or chemotactic behavior. The significant reduction in Il-6 expression upon silencing key components of the pathway underscores the critical role of the NF-kB pathway in modulating inflammatory responses within the BM microenvironment. Moreover, the transient nature of gene silencing via GapmeRs ensures the safety and reversibility of changes, making this approach viable for potential clinical applications.

The combination of silencing genes from the NF-kB signalling pathway with the previously proven silencing of Sfrp1 in endogenous MSCs (12,14) could synergistically enhance the pro-osteogenic properties of osteoporotic MSCs. Our previous research has shown that silencing Sfrp1—an inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway—leads to a 30 % increase in osteogenic potential (14). Therefore, combining the silencing of Sfrp1 with key genes from the NF-kB signalling pathway may further amplify the regenerative effects, offering a robust strategy to fight osteoporosis and other bone-related conditions. Future research should focus on in vivo studies to validate these findings and explore the long-term effects of combined pathway modulation on bone homeostasis and regeneration. Additionally, investigating the interplay between NF-kB and other signalling pathways involved in MSC differentiation and function could provide deeper insights into optimizing regenerative strategies.