In recent years, there has been a considerable rise in the use of social networks, technology, the internet and digital tools for maintaining interpersonal, especially romantic, relationships (Reyes, 2020). While they represent, to a certain extent, a mere extension of the traditional interactive functions of keeping or losing contact with others, they have also facilitated the use of various techniques for breaking up a relationship, such as ghosting (Biolcati et al., 2021). This type of online behaviour consists of suddenly or gradually interrupting or cutting off all communication with a partner, as a means of unilaterally terminating the communication and, as a result, the romantic relationship (LeFebvre, 2017). This action can therefore be interpreted as a way of ending a relationship in which there was a romantic interest or bond (Koessler et al., 2019a). Although the idea of ending a relationship by interrupting all communication has certainly existed for a long time, nowadays, due to the massive increase in the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in relationships, ghosting has been shown to be an emergent strategy in romantic relationships (Freedman et al., 2019). Aspects of this behaviour include: a) not responding to phone calls or messages, b) stopping following or blocking the partner on social networks, c) allowing posts to be marked as “seen” but not responding to them, and d) gradually reducing communication (Navarro et al., 2020a). This behaviour differs from other relationship termination strategies because the rejected partner often has no idea what has happened, as there has been no verbal explanation of the disinterest; as a result, the rejected partner has to try to interpret what the other person’s lack of communication implies (Freedman et al., 2019; Navarro et al., 2020a).

According to recent research, certain factors which could encourage this behaviour have been linked to the increased use of technology, especially the use of online communication with a romantic interest that occurs in couples, which involves certain conditions and risks, including a) the perception of flexibility in the partner’s level of commitment, b) the minimization of discomfort when rejecting unwanted suitors, c) the lack of eye contact and general depersonalization, which makes it easier to end a relationship, and d) the risk of a increasing lack of interest in the romantic relationship. Thus, those involved in the relationship may experience greater changeability and variability in online emotional relationships, since the online context makes it easier both to start relationships and to end them, due to the relative anonymity, disinhibition, and/or fewer social consequences involved when rejecting someone online (Rad & Rad, 2018; Reyes, 2020; Timmermans et al., 2020).

It therefore follows that ghosting can be considered a form of psychological and emotional partner violence, since it is a passive-aggressive interpersonal tactic which generates a feeling of helplessness and prevents the possibility of asking questions, expressing emotions or receiving feedback, all of which could help the rejected partner to process emotionally the painful experience of rejection and breakup (Rad & Rad, 2018); it can also cause an emotional impact on the victims when they are rejected, which includes feelings of surprise, uncertainty, anger, sadness, and confusion. The experience of being rejected is understood by the victim as unfair, especially since no explanations are given (Pancani et al., 2021), and such a lack of confrontation can eventually lead victims to consider that they were the guilty party responsible for the breakup (LeFebvre, 2017).

Another key aspect to consider is that the excessive use of mobile devices and social networks in romantic relationships leads to the emergence of abusive dating behaviour, as it creates more opportunities for perpetrators to carry out abusive behaviour, thus increasing the risks for victims (Víllora et al., 2019). Here, Navarro et al. (2020b) identify a significant association between increased internet use, time and online activity, and a greater risk of involvement in various manifestations of psychological violence in couple relationships (cyberdating abuse, CDA), including romantic ghosting (Biolcati et al., 2021). Furthermore, the more people follow their online friends and acquaintances on social networks, the more likely they are to be initiators and recipients of ghosting (Navarro et al., 2020b). Similarly, Timmermans et al. (2020) recognize that the increased use of online platforms could encourage ghosting by providing the tools which facilitate it, such as the possibility of blocking or deleting applications in order to interrupt the communication.

A recent study by Powell et al. (2021) also suggests that involvement in ghosting could be related to greater use and abuse of ICT, and therefore, the excessive use or addiction to social networks -in other words, the uncontrolled use of online applications- could be related to a greater risk of ghosting. Although there has been little research into it, this association may not only contribute significantly to our understanding and to the conceptual definition of this phenomenon in the romantic context but may also provide new insights into the existing relationships between the various aspects of behaviour displayed in the area of online relationships (Rosero-Bolaños et al., 2022).

As regards the consequences of ghosting, studies such as those by Timmermans et al. (2020) and Navarro et al. (2020a) suggest that it has an impact on the victims’ self-esteem, general well-being and mental health, as they feel powerless to defend themselves and see themselves as increasingly lonely. Along these lines, Rad and Rad (2018) conclude that ghosting can cause the contradictory feelings of relief at ending a relationship, mixed with uneasiness at the way the other person rejects or is rejected. Lefebvre and Fan (2020) examined victims’ strategies to reduce their feelings of uncertainty when experiencing ghosting, and found that they process uncertainty and ambiguity by changing the way they select a partner and seek better interpersonal communication in the future to avoid repeating the experience.

As for measuring the phenomenon of ghosting, there have been very few studies which present scales or questionnaires, and a complete lack of studies in the Latin American context. Vagaš and Miško (2018) designed an instrument to evaluate and predict ghosting in the workplace, exploring the relationships and communication between employees of a company where no sentimental interests were involved. After the factor analysis, a single factor was identified, which they called the Global Ghosting Indicator, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .95. They came to the conclusion that employee ghosting is a form of negative behaviour, predominantly aimed at ignoring and avoiding contact between members of the same company. Recently, Jahrami et al., (2023) designed the GHOST scale (The Ghosting Questionnaire) based on Shannon-Weaver’s (1949) communication theory, to explore the experience of ghosting from the victim’s perspective. As a result, a unidimensional scale composed of eight items was validated which evaluates aspects such as negligence, delay in responding, ambiguity, communication barriers, absence, inconsistency in responding, vulnerability, and withdrawal on the part of the “ghosters”. The final scale reported optimal psychometric properties for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, as well as adequate reliability values (Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega = .74). In the Colombian context, there have been very few studies on ghosting. Pinzón-Salcedo (2019) found, in the romantic context, that the perpetrators avoid confrontation, while victims face “symbolic grief” as they are denied a traditional breakup; instead, although some breakups are definitive, they are more often gradual, with postponed conversations and cancelled arrangements, until the relationship finally fizzles out when contact is totally lost.

Without belittling the contribution made by these studies, they mainly focus on processes of general interpersonal communication and ghosting in the workplace; it is therefore necessary to advance in our knowledge of how to measure ghosting specifically in the context of romantic relationships, considering the roles involved from the theory of roles in relationship violence and focusing on exploring the emotional impact caused.

Taking all this into account, the present study aims to analyse the psychometric properties of a romantic ghosting scale designed for a Colombian sample. As well as assessing the roles of involvement and the emotional impact of ghosting (a pioneering proposal in the Latin American and Colombian context), the scale analyses its place in the framework of addiction to social networks, which is on the rise in young adults, and where there is generally agreed to be a gap in our knowledge about how the construct relates to this condition. The starting hypothesis is that the Romantic Ghosting Scale (RG-C) will show optimal psychometric properties for a Colombian sample.

Method

Participants

The sample was incidental and consisted of 691 young adults aged between 18 and 40 (M = 24.03; SD = 4.47), of whom 62.4% (n = 431) were women and 37.6% (n = 260) were men. A 65.8% of the participants were from the city of Pasto, and 34.2% from other areas of Colombia, with 86.5% from urban and 13.5% from rural areas. The education levels were 19.8% high school, 8.2% technical, 3.9% technological, 60.1% undergraduate, and 8% postgraduate. Regarding marital status, 67% of participants were single and 33% reported having a partner. As for the socioeconomic stratum of the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), 32.4% of the participants belonged to the low-low stratum (1), 40.5% to the low stratum (2), 20.8% to the medium-low stratum (3), 5.6% to the middle stratum (4), and 0.6% to the medium-high stratum (5). The average time of use of social networks was 53.9% between 4 to 8 hours a day and 46% from 1 to 3 hours a day.

Instruments

The RG-C scale was designed from the theory of ghosting and adapted to relational violence, allowing us to delimit the role of involvement and the emotional impact of the phenomenon. The starting model contains two dimensions which assess the roles of victim and aggressor, including behaviour such as blocking profiles, gradual termination of communication, not responding to messages, making excuses to avoid explanations, and the normalization of ghosting; the third dimension assesses the emotional impact, such as perceived sadness and anger, feelings of guilt, injustice, uncertainty, and confusion (Freedman et al. 2019; Koessler et al. 2019a; Koessler et al. 2019b; LeFebvre, 2017; Navarro et al., 2020a). Initially, three experts (two in the theory of ghosting and one in psychometrics) were responsible for the content validity, assessing the pertinence, relevance, and clarity of the items; next, a pilot test was carried out to assess how easy the items were to understand. By following these procedures, an initial scale of 18 Likert-type items was produced. The first 10 items are assessed using a dual response system based on the premise: “How often does/did the person use this behaviour against you?”; “How often do/did you use this behaviour against them?” Next, we proceeded with the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the scale, and finally a correlation was made with the variable of addiction to social networks. To do this, we used the Social Network Addiction Questionnaire (SNA), validated for Colombia by Rosero-Bolaños et al. (2022). This is made up of 24 Likert-type items, divided into three factors: 1) Obsession with social networks (OB), 2) Lack of personal control in the use of social networks (LPC), and 3) Excessive use of social networks (EU). The original SNA reports optimal internal consistency values for both the total scale (total α = .95) and for each factor: αOB= .93; αLPC= .82; αEU= .89 (Rosero-Bolaños et al., 2022).

Procedure

The study was instrumental and transversal, with a single group (Ato et al., 2013), and it presented a minimal risk to the integrity and mental health of the participants, as it did not exceed the risks usually found in daily life (American Psychological Association, 2017). The research was framed in Law 1090 dated 2006 (Congreso de la República de Colombia, 2006), and Resolution 8430 dated 1993 (Ministerio de Salud de Colombia, 1993), which establish the scientific, technical, and administrative standards for health research in Colombia. The provisions of the Helsinki Declaration (WMA, 1964) were fully met. The study was endorsed by the ethics committee of the University of Nariño within the framework of Agreement No. 60 dated March 2023 (Vice Chancellor’s Office for Research and Social Interaction). The participants were of legal age and were given information regarding the objectives and methodology of the study. The voluntary and anonymous nature of participation in the study was emphasized at all times. The data was collected using the Google forms platform, for which an informed consent form was signed.

Data analysis

First, we performed descriptive analyses, both on the sociodemographic variables and on the items of the scales. A Mardia analysis was included to determine the presence or absence of multivariate normality in the data using the R program (R Development Core Team, 2008) and the MVN library (Kormaz et al., 2015). Next, content validation was carried out by expert judges and the V-Aiken index was obtained for each item. The judges were selected using the criteria proposed by Skjong and Wentworth (Escobar & Cuervo, 2008) of: a) experience, b) reputation in the scientific community, c) availability and motivation, and d) impartiality.

To validate the construct, cross-validation was carried out, which consists of dividing the total sample into two random subsamples, the first used for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the second for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This procedure follows the classic practice of making sequential use of the two analyses to explore the distribution of the items and then confirm the basic theoretical model of the measurement scale (Brown, 2006; Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). The EFA was carried out using the Factor 9.2 program (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006), taking into account the Kaiser Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy indices, Bartlett’s sphericity, communality values, item saturations, factorial loadings obtained in the distribution of the configuration matrix, and total variance explained. The principal axis extraction method and the promax rotation method were used. In the EFA process, items with communalities below .30 and saturations below .40 were rejected (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014).

The CFA was carried out using the EQS 6.2 program (Bentler & Wu, 2012); to do this, we chose the least squares (LS) estimation method with robust scaling (Bryant & Satorra, 2012), which is recommended for categorical variables when there is no multivariate normality (Morata-Ramírez & Holgado-Tello, 2013). To assess the fit of the models, the following indices were used: Satorra-Bentler chi-square (χ2S-B) (Satorra & Bentler, 2001), chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df) (≤ 5), the comparative fit index (CFI) (≥ .90), the non-normality fit index (NNFI) (≥ .90), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (≤ .07), and the root mean square value of the covariance residuals (SRMR) (≤ .07) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was also assessed to compare the models obtained: the lower the value, the better (Brown, 2006).

The internal consistency analysis was carried out using the McDonald’s omega index (ɷ ≤ .70), which is recommended for categorical variables in which there is no multivariate normality (Elosua-Oliden & Zumbo, 2008), calculated with the Factor 9.2 program (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006). Composite reliability (CR) was also measured, which indicates the general reliability of a set of items, with a CR cut-off value of .70 (Hair et al., 2005; Raykov, 1997). To assess the correlation between the variables, the Rho Spearman with the social network addiction scale was used, with a significance level of .05.

Results

The Mardia analysis yielded an asymmetry coefficient of 171.68 (p < .001) and a Kurtosis coefficient of 69.38 (p < .001), which indicates non-compliance with the assumptions of multivariate normality, and descriptive analyses were obtained for both the general scale and for each of the items (Table 1). From the EFA, 3 items with communalities below .30 and saturations below .40 were rejected (RV - RA 6; IE 16 and 17), leaving a total of 15 global items, of which the first 10 were divided into two categories (aggression and victimization).

Table 1. Table of descriptive statistics and response frequencies for each item.

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Sk | K | Fr/% | Fr/% | Fr/% | Fr/% | Fr/% | ||

| 1. | RA | 2.40 | 1.21 | 0.49 | -0.66 | 191/27.6% | 168/24.3% | 170/24.6% | 75/10.9% | 43/6.2% |

| RV | 2.44 | 1.13 | 0.37 | -0.64 | 156/22.6% | 166/24% | 185/26.8% | 76/11% | 29/4.2% | |

| 2. | RA | 1.91 | 1.20 | 1.14 | 0.21 | 359/52% | 113/16.4% | 99/14.3% | 48/6.9% | 34/4.9% |

| RV | 2.02 | 1.14 | 0.86 | -0.24 | 277/40.1% | 135/19.5% | 120/14.4% | 53/7.7% | 21/3% | |

| 3. | RA | 2.55 | 1.31 | 0.32 | -1.05 | 198/28.7% | 134/19.4% | 164/23.7% | 109/15.8% | 62/9% |

| RV | 2.53 | 1.21 | 0.30 | -0.85 | 164/23.7% | 146/21.1% | 183/26.5% | 95/13.7% | 41/5.9% | |

| 4. | RA | 2.42 | 1.23 | 0.46 | -0.76 | 202/29.2% | 161/23.3% | 176/25.5% | 84/12.2% | 46/6.7% |

| RV | 2.46 | 1.14 | 0.46 | -0.76 | 156/22.6% | 166/24% | 193/27.9% | 74/10.7% | 34/4.9% | |

| 5. | RA | 2.30 | 1.30 | 0.65 | -0.72 | 257/37.2% | 144/20.8% | 139/20.1% | 72/10.4% | 58/8.4% |

| RV | 2.31 | 1.21 | 0.61 | -0.50 | 195/28.2% | 140/20.3% | 153/22.1% | 49/7.1% | 40/5.8% | |

| 7. | RA | 2.02 | 1.23 | 0.98 | -0.15 | 327/47.3% | 133/19.2% | 108/15.6% | 58/8.4% | 39/5.6% |

| RV | 2.06 | 1.17 | 0.89 | -0.09 | 255/36.9% | 137/19.9% | 120/17.4% | 41/5.9% | 29/4.2% | |

| 8. | RA | 1.72 | 1.12 | 1.49 | 1.24 | 418/60.5% | 98/14.2% | 82/11.9% | 34/4.9% | 28/4.1% |

| RV | 2.02 | 1.17 | 0.90 | -0.15 | 257/37.2% | 111/16.1% | 114/16.5% | 40/5.8% | 25/3.6% | |

| 9. | RA | 2.53 | 1.25 | 0.40 | -0.86 | 174/25.2% | 180/26% | 159/23% | 102/14.8% | 55/8% |

| RV | 2.44 | 1.12 | 0.40 | -0.49 | 141/20.4% | 156/22.6% | 185/26.8% | 58/8.4% | 30/4.3% | |

| 10. | RA | 1.82 | 1.09 | 1.23 | 0.63 | 359/52% | 146/21.1% | 92/13.3% | 44/6.4% | 21/3% |

| RV | 2.12 | 1.12 | 0.74 | -0.26 | 221/32% | 143/20.7% | 136/19.7% | 42/6.1% | 22/3.2% | |

| 11. | EI | 2.99 | 1.28 | 0.00 | -1.01 | 108/15.6% | 133/19.2% | 195/28.2% | 133/19.2% | 105/15.2% |

| 12. | EI | 3.35 | 1.27 | -0.31 | -0.95 | 69/10% | 114/16.5% | 165/23.9% | 182/26.3% | 154/22.3% |

| 13. | EI | 2.88 | 1.19 | -0.08 | -0.81 | 102/14.8% | 154/22.3% | 221/32% | 131/19% | 73/10.6% |

| 14. | EI | 3.34 | 1.47 | -0.35 | -1.25 | 115/16.6% | 75/10.9% | 118/17.1% | 128/18.5% | 195/28.2% |

| 15. | EI | 3.96 | 1.19 | -1.00 | 0.07 | 39/5.6% | 48/6.9% | 114/16.5% | 173/25% | 302/43.7% |

| 18. | EI | 3.15 | 1.36 | -0.17 | -1.14 | 109/15.8% | 104/15.1% | 162/23.4% | 146/21.1% | 137/19.8% |

Note.1 = Never/No, 2 = Hardly ever/On few occasions, 3 = Sometimes/Maybe, 4 = Nearly always/I probably would, 5 = Always/I definitely would; Fr = Frequency, Sk = Skewness, K = kurtosis, RV = Role of victim, RA = Role of aggressor, EI = Emotional impact.

As for the content validation, the judges suggested that the wording of some items be changed. The V-Aiken values for each item and for validity were optimal, obtaining a V-Aiken Total = .88 (V-Aiken pertinence = .9; V-Aiken clarity = .93, and V-Aiken relevance = .83), which indicates a high level of agreement and concordance between the judges. Item 7 obtained the lowest score (.67). Once the adjusted version was obtained, a pilot test was carried out with 38 young adults to evaluate how easy the items were to understand. We received five comments suggesting improvements to the wording of some of the statements.

As regards the construct validation, the EFA analysis indicated a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin-KMO sample adequacy test of .811, and a significant Bartlett sphericity (χ2= 5021.69; df = 276; p ≤ .001). The communalities (h2) ranged between .307 (item RA-7) and .692 (item IE-14), which are acceptable results. Next, the factorial configuration was verified with a free distribution which suggests that all the items are distributed in three factors, which is consistent with the theoretical dimensions proposed; the factor saturations were also optimal and ranged between .511 (item RA-5) and .830 (item IE-14), making a total explained variance of 47.02% (Table 2).

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of the Ghosting Scale.

| Dimension/factor | Item | F1 | F2 | F3 | h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression/perpetrator (You to him or her) | RA-1 | .643 | .419 | ||

| RA-2 | .645 | .416 | |||

| RA-3 | .776 | .604 | |||

| RA-4 | .719 | .526 | |||

| RA-5 | .511 | .309 | |||

| RA-7 | .531 | .307 | |||

| RA-8 | .604 | .386 | |||

| RA-9 | .596 | .359 | |||

| RA-10 | .667 | . | .442 | ||

| Victimization (He or she to you) | RV-1 | .608 | .383 | ||

| RV-2 | .670 | .457 | |||

| RV-3 | .706 | .502 | |||

| RV-4 | .722 | .552 | |||

| RV-5 | .695 | .485 | |||

| RV-7 | .648 | .421 | |||

| RV-8 | .615 | .393 | |||

| RV-9 | .653 | .441 | |||

| RV-10 | .659 | .442 | |||

| Emotional Impact | EI-11 | .741 | .556 | ||

| EI-12 | .806 | .659 | |||

| EI-13 | .727 | .534 | |||

| EI-14 | .830 | .692 | |||

| EI-15 | .706 | .502 | |||

| EI-18 | .707 | .521 | |||

| Explained variance | 6.28% | 26.71% | 14.02% | ||

| Total variance explained | 47.02% | ||||

Note.Extraction method: Main Axes. Rotation: promax. h2= communalities.

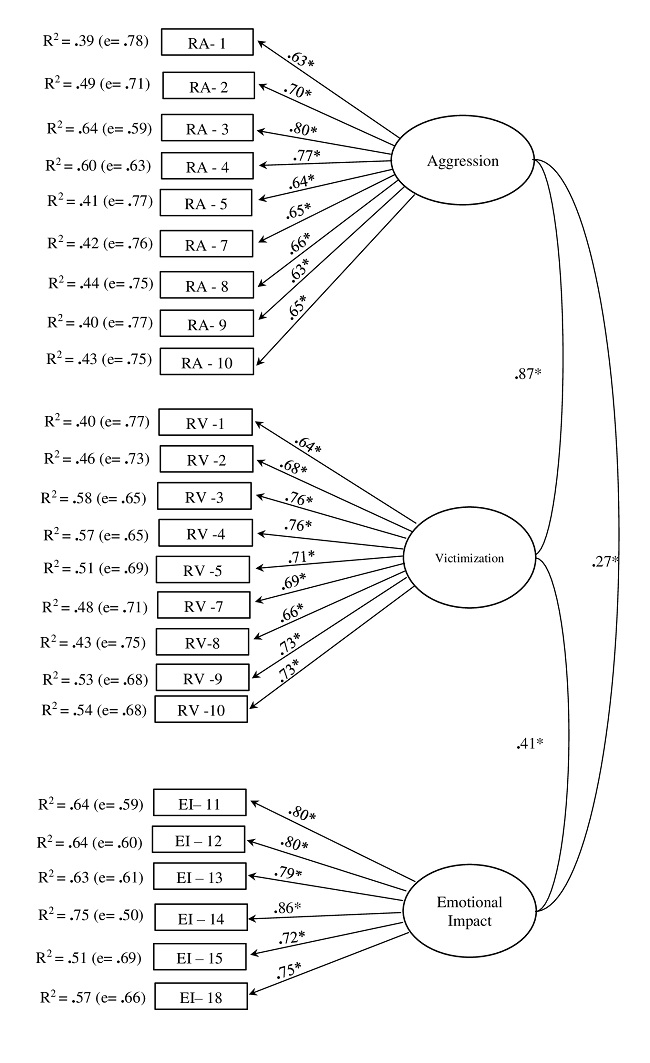

The CFA of the 3-factor structure suggested by the EFA showed optimal fits, in addition to adequate factor weights and measurement errors: χ2S-B = 411.14; χ2S-B/ (249)= 1.65; p < .001; NNFI = .990; CFI = .992; RMSEA = .042 (90% CI [.035, .049]); SRMR = .075; AIC = 1310.32 (see Figure 1).

The internal consistency values of Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ɷ) obtained for the factors of the romantic ghosting questionnaire were optimal, as were the composite reliability (CR) indices (see Table 3).

Table 3. Internal consistency values.

| Scale | Factor/dimension | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | McDonald’s Omega (ɷ) | Composite Reliability (CR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RG-C | RV | .90 | .91 | .89 |

| RA | .86 | .88 | .89 | |

| IE | .87 | .88 | .89 | |

| SNA | SMO | .89 | .90 | --- |

| LPC | .79 | .81 | --- | |

| EU | .87 | .83 | --- |

Note.RV = Role of victim; RA = Role of aggressor; SNA = Social networks addiction; SMO = Social media obsession; LPC = Lack of personal control; EU = excessive use of social networks.

Finally, the correlations with the dimensions of the Social Network Addiction Scale indicated a moderate, low value respectively; .331 (p ≤ .01) between the emotional impact of ghosting and excessive use of social networks and .281 (p ≤ .01) between the emotional impact of ghosting and lack of personal control.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to analyse the psychometric properties of a ghosting scale designed for the romantic context (RG-C) in young Colombian adults. The design of the instrument started from the theoretical basis that romantic ghosting can be understood as a way of ending romantic relationships by interrupting or cutting off all the implicit communication in a relationship through the use of electronic devices and the internet (Freedman et al., 2019; Koessler et al., 2019a). This enabled us to check the theoretical robustness of the three-factor model: the role of the aggressor, the role of the victim, and emotional impact. These dimensions were initially subjected to content validation, the results of which suggested that the conceptual structure which was used to later design the items meets the criteria of clarity, relevance and pertinence. As regards construct validity, the EFA suggested that the items are distributed in a way that fits in with the three theoretical dimensions proposed. During the process, we had to delete three items. Next, the CFA confirmed these three factors, highlighting the possibility of evaluating the extra value of emotional impact, unlike the existing scales, which focus only on assessing the communication processes occurring in the role of involvement.

Factor analysis, in general, highlights the relevance of evaluating specific behaviour that perpetrators use against victims, such as cutting off communication, not answering calls, and blocking the other person on social networks or applications in order to end a relationship (or potential romantic relationship) without giving any explanation. These findings help confirm the importance of analysing the roles of involvement in ghosting (Navarro et al., 2020a), and complement our understanding of the duality of the phenomenon as described in some studies, which distinguish between the non-initiators/recipients and the initiators/“ghosters” (Koessler et al., 2019b; LeFebvre, 2017). Along these lines, one of the relevant items in the “role of the aggressor” factor of the CFA was the one referring to gradually reducing contact (RA-3), which is probably one of the commonest practices used by perpetrators; this aspect is reflected in the “role of the victim” factor (RV-3), since this item scored highly in the statistics, suggesting that this practice is a key part of the construct and should be seen as a common way of terminating a relationship with sentimental interest. This finding agrees with the research of Koessler et al. (2019a) and LeFebvre and Fan (2020), who also found this to be the most widespread kind of behaviour, and that the speed with which it happens can vary from a gradual decrease to the sudden termination of all contact.

As for the second factor, “role of the victim”, one of the key aspects is the important contribution of the item that assesses the use of excuses or pretexts to avoid communication (RV-4), by which victims of this phenomenon receive excuses or pretexts from the aggressor to avoid communication, thus ending the relationship. As Vagaš and Miško (2018) explained, interrupting communication by avoiding the people affected is a common practice in ghosting.

Regarding the dimension of “emotional impact”, both the EFA and CFA corroborate that it is necessary to take into account the emotional responses associated with the phenomenon to produce an accurate, up-to-date theoretical delimitation of the construct. It is widely recognized, therefore, that perceived emotions such as sadness, anger, confusion, and guilt are key features, in line with the studies by Rad and Rad (2018), Navarro et al. (2020a), and Pancani et al. (2021), who showed how being ignored online and experiencing the breakup of a romantic relationships is linked to these feelings, and that it increases the risk of psychological distress, emotional dysregulation, loneliness, and anxiety. Likewise, indifference or isolation in interactive online contexts can be considered a form of passive violence, since the person who suffers indifference can be emotionally affected (Lucio et al., 2018). One of the items in the CFA that contributes significantly to measuring this dimension refers to feeling angry when the partner, or potential partner, “blocks” you from social networks without giving any explanation (IE-14). This agrees with Pancani et al. (2021), who highlighted that the abrupt termination of communication leads to victims of ghosting experiencing greater anger, especially if the reasons for the breakup are considered unfair.

Regarding the correlations between the dimensions of ghosting and addiction to social networks, the results showed a low-moderate link between these constructs, which is a positive finding, since ghosting is conceptually different from the notion of behavioural addiction, although they share certain aspects of behaviour and components. The analysis suggests that despite being different concepts, they show a certain degree of association because they both occur in the online context. Although both phenomena take place when using social networks, addiction is more focused on developing intrapersonal processes aligned with dependency and abuse, while ghosting focuses more on interpersonal development supported mainly by the use of social networks to end a romantic relationship mediated by technology. Thus, the analyses show a link between the emotional impact of the ghosting scale and a lack of personal control and excessive use of social networks, which opens up the possibility of understanding the place of this phenomenon in the use of technology, and suggests that such abuse can eventually affect the decision to use ghosting in relationships. These findings are consistent with Powell et al. (2021), who suggested that the use of ghosting goes hand in hand with an increased use of technology in romantic relationships. Thus, excessive use and addiction to social networks could probably lead to a greater risk of involvement in the different roles of ghosting, and therefore a greater emotional impact.

In conclusion, the RG-C scale shows optimal psychometric properties in terms of content and construct validity, in addition to optimal reliability values, which demonstrates its suitability and basic theoretical robustness, meaning that it can be used to measure romantic ghosting in a population of young Colombian adults.

This study contributes to the field of research into online violence with a pioneering scale for Colombia which allows us to measure this emerging online behaviour used when couples break up. Finally, the results of this study could also have practical implications by guiding therapeutic or psycho-educational processes aimed at managing the impact of a romantic breakup carried out on ICT. Similarly, the study opens up future lines of research, such as the study of guilt in ghosting and the theoretical differentiation between phenomena such as cricketing, benching, haunting, cushioning, and breadcrumbing, among others.

This study has its limitations, such as the size and type of sample and the use of self-administered questionnaires, which can be affected by social desirability, in addition to the fact that the cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to measure the impact of the phenomenon over time. We suggest that in future research, longitudinal studies could be used, extending the study sample and analysing behaviour at a range of ages and in different cultural contexts.

texto en

texto en