Humiliation represents a complex construct that can be understood as an interaction in which an individual is led by others to a position of subjugation or inferiority, but also as a distinctive emotion, experienced by victims who are subjected to a degrading or insulting act (Fernández et al., 2015; Hartling & Luchetta, 1999; Walker & Knauer, 2011). Various authors have emphasized the severity and intensity that characterize humiliation on a psychological level (Lindner, 2002; Otten & Jonas, 2014). Stewart et al. (2019) identified it as one of the most frequent aversive experiences in social contexts, where its impact can influence collective judgments and values (Barnhart, 2020; Gerson, 2011; Palshikar, 2005), publicly attacking personal and/or group dignity (Gilbert 1997; Kaufmann et al., 2011; Statman, 2000).

Bullying, or harassment, consists of behavior aimed at causing harm to a victim, and is characterized by its intentionality, its temporal repetition, and by the existence of power imbalance between the parties involved. (Olweus, 1993). Traditionally, bullying has been studied as a social dynamic between peers within the school environment; however, it is not an exclusive phenomenon of said context, since it can involve other participants, such as the harassment that a teacher exerts on a student (Twemlow & Fonagy, 2005), and occur in different environments, as is the case of workplace bullying (Żenda et al., 2021).

Numerous studies highlight that humiliation and bullying are closely related phenomena (Barrett & Scott, 2018; Kafle et al., 2022; Kaplan & Mutchinik, 2019; Merle, 2005; Thomaes et al., 2011; Walker & Knauer, 2011), based on the fact that being the target of abuse involves personal degradation (Harter et al., 2003; Markman et al., 2019; Meltzer et al., 2011). This results in disturbing and traumatic interactions for victims that can culminate in very serious and long-lasting consequences (Elison & Harter, 2007; Leask, 2013). In this sense, humiliation has been linked to extremely alarming outcomes, such as terrorism (Lindner, 2001; McCauley, 2017), genocides (Lindner, 2002; Strozier & Mart, 2017), massacres in educational centers (Aronson, 2001; Harter et al., 2003; Larkin, 2009), psychopathologies (Collazzoni et al., 2017; Farmer & McGuffin, 2003; Selten & Ormel, 2023; Toh et al., 2023), or suicide (Sadath et al., 2024; Torres & Bergner, 2012).

Consequently, victimization resulting from bullying points humiliation as a crucial variable (Collazzoni et al., 2017; Fisk, 2001; Markman et al., 2019; Meltzer et al., 2011; Merle, 2005), because it is a common emotion that harms the personal and social well-being of the victims (Barber et al., 2013; Giacaman et al., 2007; Ortega-Jiménez et al., 2023; Vargas-Núñez, 2021). However, there are few studies that explore humiliation as a subjective experience (Fernández et al., 2023), or from a clinical point of view (Collazzoni et al., 2014; Sadath et al., 2024). This denotes that humiliation constitutes a very complex topic (Fernández et al., 2015) that has been relatively neglected within empirical research (Ginges & Atran, 2008; Leidner et al., 2012). In fact, the examination of the existing literature reveals a clear absence of consensus regarding its approach (Elshout et al., 2017), which emphasizes that its nature must be elucidated, in addition to its underlying mechanisms and its profound implications; especially the impact that it exerts on the victim of bullying, given that it is the only way to understand the relationship between these two phenomena.

The present work is intended to investigate bullying victimization from the theoretical prism of humiliation, understanding bullying as a dynamic of recurrent abuse or mistreatment that implies an imbalance of power and that takes place in specific social contexts, such as academic or work-related. For this purpose, the following objectives are established: 1) to review the concept of humiliation and its nature, according to the literature on this phenomenon; 2) to review the main consequences derived from the emotional experience of humiliation; and 3) to analyze the relationship between humiliation and bullying victimization, integrating existing evidence and offering an updated and innovative perspective on the topic in question.

Method

The methodology used corresponds to the narrative review (Sukhera, 2022). Data collection was managed by the first author between December 15 (2023) and February 15 (2024). The main database examined was PubMed, although the bibliographic sources PsycInfo, Dialnet, Latindex, Academia, JSTOR, and ResearchGate were also used. The established exclusion criteria were: 1) articles not available or not accessible; 2) articles that do not contain information related to the objectives of the study, or whose subject matter is not relevant to their achievement. The following inclusion criteria were set: 1) articles about humiliation; 2) articles about other emotions closely related to humiliation (shame and anger); 3) articles on self-conscious emotions that discuss social and clinical implications; 4) articles on bullying/harassment that consider humiliation as a variable; 5) articles on specific contexts that harbor victimization dynamics potentially mediated by humiliating acts; 6) theoretical articles that expose models related to the cognitive appraisal of the situation, emotional regulation, and/or social judgments and attributions. To carry out the search, different combinations were used with the following keywords and Boolean operators: («humiliation») AND («bullying» OR «harassment» OR «mistreatment») AND («shame» OR «anger») AND («social» OR «health») AND («consequences» OR «effects»). Likewise, the search process involved the recognition of several reference lists of studies related to the topic investigated, as well as the examination of book reviews present in the bibliographic sources consulted. No search restrictions were applied, nor was an inter-rater reliability procedure carried out. Articles in languages other than Spanish and English were examined with the help of online translation tools.

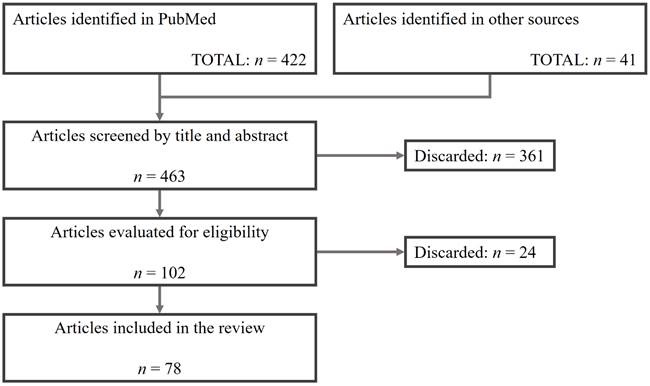

Figure 1 represents a synthesis of the article search and selection process. From a total of 463 articles identified, 361 were discarded through a screening process that involved reading the title and abstract. The remaining 102 articles were evaluated for eligibility by reading their content in full, and 24 were discarded because they did not provide relevant information for the present work or because they did not fully satisfy the established criteria.

Of the 78 articles selected to constitute the theoretical body of the review, 43.6% are original articles, 42.3% are review articles, 11.5% are books or book chapters, 1.3% are opinion articles, and 1.3% are case studies. Regarding the language of the articles, 93.6% of them are written in English, 2.6% in Spanish, 1.3% in French, 1.3% in Italian, and 1.3% in Polish. Regarding the year of publication, 2.6% were published between 1960 and 1969, 3.8% between 1980 and 1989, 7.7% between 1990 and 1999, 20.5% between 2000 and 2009, 43.6% between 2010 and 2019, and 21.8% after 2020. Finally, in relation to the geographical context, 42.3% of the publications belong to the United States, 11.5% to the United Kingdom, 7.7% to the Netherlands, 6.4% to Spain, 3.8% to Italy, 3.8% to Norway, 2.6% to Australia, 2.6% to Canada, 2.6% to Poland, and 1.3% to each of the following countries: Argentina, Belgium, China, Finland, France, India, Ireland, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Palestine, Sweden, and Switzerland. Information regarding the characteristics of the selected articles is shown in Supplementary table 1.

Results

Humiliation: concept and nature

Humiliation began to be conceptualized as an aversive experience linked to the internalization of a painful stimulus (Spiegel, 1966). The approach to this phenomenon as an aversive experience is coherently connected with other later approaches (Payne, 1968; Rothstein, 1984), in which the fear of humiliation is highlighted as a barrier that discourages individual achievement in order to avoid public affront (Hartling & Luchetta, 1999). These early approaches accentuated an emotional and a social facet of humiliation, and also made visible its evident hurtful nature, underlining the importance of analyzing its manifestations and implications in different contexts and situations (Kaufmann et al., 2011; Lazare, 1987; Miller, 1988).

The literature review reveals that humiliation has been the subject of multiple conceptualizations over time (Collazzoni et al., 2014; Elshout et al., 2017). The social field of psychology has focused on studying it as a self-conscious emotion (Fernández et al., 2015). These emotions arise from the evaluation of one’s behavior with respect to social standards, and are characterized by an awareness that emerges from external reactions towards oneself (Park & Lewis, 2021). Therefore, they fulfill an adaptive function (Sznycer, 2019) and play a fundamental role in the construction of self-concept (Conroy et al., 2015). In this sense, the threat related to a devalued self-representation can produce great deterioration at a personal level (Dickerson et al., 2008; Merle, 2005), since negative judgments by others determine the way in which people perceive themselves within a social framework (Alicke et al., 2005). Thus, humiliation is defined as a particularly intense self-conscious emotion (Otten & Jonas, 2014), which arises when a person is unfairly degraded by others, so that a devaluation of the “self” can be internalized (Fernández et al., 2015; 2018).

Diverse studies have linked humiliation with shame (Elshout et al., 2017; Klein, 1991; Lazare, 1987; Leidner et al., 2012; Miller, 1988), determining the differential aspects (Dorahy, 2017; Fernández et al., 2015; Gilbert, 1997), and even equating these two emotions (Elison & Harter, 2007; Hartling & Luchetta, 1999; Thomaes et al., 2011). The latter has been questioned, since humiliation is associated with vindictive results that are unrelated to shame in its strictest sense (Elshout et al., 2017). However, it is important to consider that shame is a term that can represent different types of emotional experience depending on the language: in the Spanish-speaking context, shame can be understood as something similar to embarrassment or shyness, but also as an intense emotion that emphasizes a social concern for image and public reputation (Hurtado-de-Mendoza et al., 2010; 2013). Referring to this second meaning of the term, the literature shows that there are common elements between shame and humiliation, given that both self-conscious emotions share a negative view of oneself (Gilbert, 1997) and involve the internalization of a devalued identity (Fernández et al., 2015). On the other hand, this shared devaluation is only perceived as unfair in the case of humiliation (Elison & Harter, 2007; Fernández et al., 2015; Miller, 1988); while the experience of shame is more focused on the judgment that arises when one’s own or social ideals are not achieved (Dolezal, 2022; Klein, 1991). Such a distinction confirms that shame involves a personal sense of responsibility that in the experience of humiliation is attributed to other people (Dorahy, 2017; Gilbert, 1997). In light of the above, it is worth highlighting the “paradox of humiliation”, which refers to the contradiction resulting from internalizing a devaluation of the “self” imposed by others if it is considered unfair (Fernández et al., 2015).

Another emotion frequently associated with humiliation is anger (Combs et al., 2010; Elshout et al., 2017; Harter et al., 2003; Negrao et al., 2005), based on the fact that both share the appraisal of unfairness (Elison & Harter, 2007; Fernández et al., 2015) and the impulse to retaliate (Cramerus, 1990; Torres & Bergner, 2012). Despite these convergences, the individual entity seems to play a very different role in these two emotions: unlike anger, humiliation involves the actions of others being experienced as an exposure of self-perceived deficiencies (Negrao et al., 2005). Thus, humiliation entails a loss of power and authority that could explain how this emotion leads to behavioral passivity that hides a desire for confrontation (Leidner et al., 2012).

In relation to the above, it has been postulated that the factor that allows us to differentiate shame and anger from humiliation lies in the two cognitive appraisals that uphold this last emotion. Fernandez et al. (2015) establish that 1) people who simultaneously experience devaluation and unfairness are more likely to feel humiliated; while 2) those who internalize a devaluation that they do not consider unfair tend to feel shame; and 3) those who do not internalize devaluation, but do perceive unfairness, are more susceptible to feel anger.

Consequences of humiliation

In accordance with the cognitive duality that characterizes humiliation (Fernández et al., 2015), it has been related to discrepant behavioral tendencies (Leidner et al., 2012). On the one hand, humiliation can trigger an active confrontation based on violent behavior (Aronson, 2001; Barnhart, 2020; Larkin, 2009; Lindner, 2002; Thomaes et al., 2011; Torres & Bergner, 2012; Walker & Knauer, 2011) that is commanded by an intense desire for revenge (Cramerus, 1990; Elison & Harter, 2007; Lindner, 2001; Strozier & Mart, 2017); and on the other hand, humiliation can be responsible for an absence of confrontation in which the victim tends to avoidance (Mann et al., 2016), to inaction (Ginges & Atran, 2008; Leidner et al., 2012), or even to a state of helplessness (Leask, 2013) that culminates in suicide (Meltzer et al., 2011; Sadath et al., 2024; Torres & Bergner, 2012). This peculiar combination of indignation and helplessness has been interpreted as a type of “contained rage” in which violent actions are repressed, but which over time can lead to destructive consequences of different kinds and magnitudes (Ginges & Atran, 2008; Torres & Bergner, 2012). In consistent relation to the above, being a victim of humiliation has also been associated with various adverse psychological conditions (Giacaman et al., 2007; Leask, 2013), such as depression (Farmer & McGuffin, 2003), paranoia (Collazzoni et al., 2017), schizophrenia (Selten & Ormel, 2023), or psychosis (Toh et al., 2023).

Relationship between humiliation and bullying victimization

Within the framework of bullying, humiliation represents the emotion that arises in response to an interpersonal dynamic in which the victim’s “self” is threatened as a result of a demonstrative exercise of power intended to denigrate or outrage. For this reason, research focused on studying harassment considers humiliation as an emotional consequence closely linked to practices of intimidation, mistreatment and abuse (Barrett & Scott, 2018; Meltzer et al., 2011).

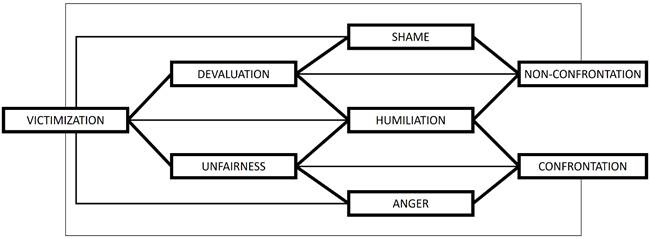

From the processual model of emotional regulation (Gross, 2014) it is possible to understand the experience of humiliation in a context of bullying victimization (Fernández et al., 2018; 2022; 2023). In this regard, the abuse exerted on victims causes them to make a cognitive appraisement of the situation that constitutes the causal determinant of their emotional response (Moors et al., 2013); in turn, the cognitive-emotional interaction of victims also influences their subsequent behavioral pattern (Chick, 2019). Considering that these associations are influenced by individual and contextual factors (Fernández et al., 2018; 2023), the harassment suffered exerts an indirect effect on the humiliation experienced via devaluation and unfairness, as well as an indirect effect on the behavior displayed through cognitive appraisals and emotional response (Figure 2).

One of the keys of the theoretical framework of emotional regulation is that the emotion experienced can change if action is taken in any of the phases of the process. Actions such as active coping or cognitive emphasis have the potential to reduce the internalization of devaluation and, therefore, to attenuate the experience of humiliation in favor of the emotion of anger (Fernández et al., 2022).

A situation in which humiliation occurs admits three perspectives: that of the perpetrator, that of the witnesses, and that of the victim (Klein, 1991). The power imbalance inherent in bullying favors the perpetrators, but exposes and degrades the victims (Collazzoni et al., 2014; Palshikar, 2005), who are unable to disengage themselves from the judgment of others due to their need for acceptance and self-respect (Statman, 2000). Fernández et al. (2018) reported that the hostility shown by the perpetrator increased the perception of unfairness underlying the humiliation and, consequently, the experience of said emotion was increased, while social status could facilitate the internalization of devaluation, also promoting the emotional response of humiliation. Markman et al. (2019) found that when an authority figure publicly humiliates a victim, one of the main influencing factors in the experience of humiliation was perceiving that the perpetrator’s actions were motivated by negative intentions. Salmivalli et al. (2021) positively correlated being a perpetrator of bullying and social status, as well as being a victim of bullying and rejection. These findings suggest that the threat to the victim’s self-concept could be conditioned by the image that witnesses form of the victim based on the characteristics of the humiliating situation, which constitutes, precisely, part of the fear that a person harbors when faced with the possibility of being humiliated (Gerson, 2011).

Although it is not an essential factor for its occurrence (Combs et al., 2010; Fernández et al., 2023; McCauley, 2017), the presence of witnesses has been considered a prototypical element of humiliation (Elshout et al., 2017), and it has been alleged that victims feel a greater degree of devaluation if the episode occurs in front of an audience (Combs et al., 2010; Elison & Harter, 2007; Walker & Knauer, 2011), especially if the audience contributes to reinforce said act (Mann et al., 2017). However, the influence of witnesses seems to be lower when there is no perceived intentionality for doing the public humiliation (Combs et al., 2010), which suggests that it could be related to the unfairness component (Walker & Knauer, 2011). In this respect, Fernández et al. (2023) confirmed that witnesses play a key role in intensifying the emotional experience of humiliation, and proposed two possible explanations for this effect: 1) the victim perceives the underlying devaluation in a more unfair way; and 2) if the devaluation is accompanied by hostility, the audience facilitates the internalization of said devaluation.

Salmivalli et al. (2021) stated that a higher predisposition to the defense promotes a lower prevalence of bullying. In general terms, victims are more likely to cope with the bullying situation through strategies focused on addressing the problem directly than through strategies aimed at managing the resulting emotions (Tenenbaum et al., 2011). In this regard, coping based on conflict resolution has been positively associated with mental health (Lai et al., 2023). Agency, understood as the victim’s ability to actively respond to the perpetrator, has been considered an important protective factor in humiliating situations (Wojciszke et al., 2011), which is closely related to the basic need for control (Fiske, 2010). Fernández et al. (2022) found that victims who actively reacted to the humiliating situation experienced this emotion to a lesser extent than those who did not. Consequently, responding with agency could mitigate the emotional experience of humiliation, due to a greater perception of control over the situation and over one’s own behavior. These findings are especially relevant in bullying contexts, since training victims to confront abuse adaptively could be an effective strategy to protect their psychological well-being (Lai et al., 2023).

Many young people are humiliated daily at school, so it is a widespread phenomenon (Elison & Harter, 2007; Merle, 2005). Humiliation in a context of school bullying is constituted as a cultural practice in which are deployed “superiorization” and “inferiorization” processes that lead victims to assume the disqualifications that others attribute to them (Kaplan & Mutchinik, 2019). This is particularly worrying, given that youth is a period of vulnerability in which such adversities can drastically impact the psychological and social well-being of those who experience them (Thapar et al., 2022; Stewart et al., 2019; Vargas-Núñez, 2021). Likewise, observational learning of humiliating acts can promote a collective moral disengagement among young people, perpetuating the social implementation of this type of behavior (Thornberg et al., 2021).

On the other hand, it has been highlighted that “public humiliation” is an exercise frequently used by teachers (Barrett & Scott, 2018; Markman et al., 2019) that has potentially harmful effects for students (Cook et al., 2014). Furthermore, a significant relationship has been demonstrated between students who reported having experienced abuse during their training and the subsequent practice of mistreatment during their professional performance (Moscarello et al., 1994; Twemlow & Fonagy, 2005). In this regard, students who have been victims are unlikely to report these episodes, either for fear of retaliation or for fear of prolonging the negative consequences of the situation (Markman et al., 2019).

Although the workplace context is not exempt from humiliating dynamics, not all of them are illegitimately conceived (Calabrò, 2021; Fisk, 2001). In fact, derogatory treatment has become so common in some professional settings that it is often ignored rather than reported (Kafle et al., 2022). Due to its nature and consequences, humiliation not only has serious repercussions at the individual level, but also corrupts the work environment and relationships between people employed in the organization (Żenda et al., 2021). For this reason, the workplace is considered one of the main sources of discrimination for certain collectives (Ortega-Jiménez et al., 2023). In this respect, it is worth noting that women are one of the groups most affected by this problem (Calabrò, 2021; Kafle et al., 2022).

Discussion and conclusions

While studies on bullying in different contexts abound, those focused on humiliation as an emotional experience are scarce. This disparity highlights the need to integrate both phenomena, since humiliation is an inherent variable in any manifestation of abuse (Meltzer et al., 2011). To this end, it is essential to adopt the perspective of victims and consider that they tend to internalize a devaluation that they perceive as unfair after having been degraded and/or exposed by others (Fernández et al., 2015).

Humiliation can be especially harmful for the victim when it is experienced in social settings, since the perception of being humiliated in front of other people can intensify the psychological impact (Fernández et al., 2023). Various studies reviewed show that, in terms of social well-being, humiliation has an extremely negative impact on those who suffer it, as well as on the prevailing normative order (Aronson, 2001; Barber et al., 2013; Giacaman et al., 2007; Ginges & Atran, 2008; Palshikar, 2005; Torres & Bergner, 2012; Vargas-Núñez, 2021). In this sense, the victim could experience difficulties in maintaining healthy interpersonal relationships as well as in establishing new bonds, due to the perception of contempt and distance and to the feelings of exclusion, degradation, and alienation (Kaufmann et al., 2011).

Considering the high prevalence of bullying in different environments (school, work, community, family), it is essential to implement measures aimed at preserving the personal and social well-being of the population. A possible key factor to mitigate the effects of this problem could lie in the promotion of strategies based on actively coping with the situation (Fernández et al., 2022). However, a multifaceted approach to this phenomenon would require the implementation of broader actions, such as promoting culture and education, encouraging social support, enforcing zero tolerance policies, and favoring both inclusion and diversity.

In summary, the humiliation resulting from bullying not only affects the victims individually, but also has a strong impact on social well-being at a more general level. Therefore, its management requires initiatives that not only focus on acting on victims, but also transform the social dynamics that allow and perpetuate harassment. Hence, it is essential to establish rules of coexistence based on respect, empathy, and collaboration, as well as the implementation of protocols that emphasize responsibility for one’s own actions and in which resources aimed at raising awareness among the population are prioritized, especially to the new generations.

texto en

texto en