There is currently a broad consensus on the importance of creating an adequate climate of coexistence to ensure the smooth functioning of schools (Álvarez et al., 2023; Guzmán & Sepúlveda, 2023). The concept of school coexistence is complex, multifaceted, and dynamic (Córdoba et al., 2016). This paper follows an operational definition, understanding coexistence as the network of relationships established between the members of the educational community, with positive coexistence being that which is based on democratic values such as mutual respect, tolerance, solidarity, or interest in the common good (Del Rey et al., 2008). In this sense, positive coexistence has been considered a clear indicator of positive school climate, giving relevance to the quality of relationships between members of the educational community (Del Rey et al., 2017). Not surprisingly, among the benefits of interventions based on the concept of positive coexistence, some of a relational nature have been highlighted, such as their capacity to foster the construction of peer support networks (Córdoba et al., 2016) or to promote the acquisition of the values necessary to live together in a democratic society (Torrego et al., 2022).

Despite the relevance of the concept, interest in school coexistence is relatively recent. In recent decades, there has been a shift from a reactive model of coexistence, based almost exclusively on the application of sanctions, to a preventive one (Carbajal & Fierro, 2021). Without rejecting the convenience of punitive measures, especially in the case of serious misdemeanours and crimes, preventive models emphasise the active participation of the school community in the construction of a positive climate of coexistence (Torrego et al., 2022). All the foregoing implies transforming pedagogical and organisational practices, integrating a perspective based on inclusion and equity that allows students to acquire the conflict resolution skills necessary to live together in a democratic society (Carbajal & Fierro, 2021).

In line with emerging coexistence management models, Organic Act 3/2020 of 29th December, amending Organic Act 2/2006 of 3rd May on Education (LOMLOE, as per its Spanish acronym), requires schools to draw up a coexistence plan. In this plan, schools must implement the activities programmed to create an appropriate climate of coexistence, as well as the rights and duties of the members of the educational community and the corrective measures in the event of infringement of the regulations (Gálvez-Algaba & García-González, 2022).

For their part, the regulations governing coexistence plans in the 17 Spanish Autonomous Communities have as a common element the consideration of educational establishments as spaces for participation that require the commitment of teachers, students, and families to improve coexistence. Therefore, they agree that schools should promote dialogue and cooperation between members of the educational community, fostering the development of pro-social behaviour (Azqueta et al., 2023).

To this end, Spanish schools have been incorporating a wide variety of actions into their coexistence plans. The Spanish Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (2023) provides for up to 18 types of programmes for the improvement of school coexistence, among which peer support programmes, bullying prevention programmes, gender-based violence prevention programmes, and gender equality programmes stand out due to their wide dissemination.

In this context, some researchers highlight the importance of peer support programmes (Andrés & Gaymard, 2014; Giménez-Gualdo et al., 2021; Torrego et al., 2021). Such programmes are based on enhancing positive interaction among students, covering a wide range of actions, such as encouraging participation, training pupil helpers, tutors and/or mediators, democratic rule-making, or the development of moral values (Avilés & Tognetta, 2021). Its main purpose is to transform schools so that they evolve towards a model of coexistence based on democratic participation and peaceful and autonomous conflict resolution (Fierro & Carbajal, 2019).

Peer support programmes have wide institutional backing. Most governments of autonomous communities recommend their implementation and promote the training of the teachers who coordinate them (Spanish Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2023). Among peer support programmes, school mediation programmes have had the greatest impact on the Spanish education system (Viana-Orta, 2019). Student helper programmes have received less attention, despite the fact that recent studies show they have positive effects on school coexistence (Bueno et al., 2023; Torrego et al., 2021) and that they are widely implemented in schools (Muslares, 2023).

Similar to other peer support programmes, student helper programmes are based on giving students an active role in building a positive climate of coexistence. After passing a selection process, student helpers are trained in social and communication skills, teamwork, emotional self-regulation, and conflict resolution (Cowie, 2020). Their duties cover functions such as favouring student inclusion, promoting dialogue in conflict situations (Avilés, 2017), or identifying bullying cases (Torrego et al., 2021).

The Strategic Plan for School Coexistence (Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport, 2017) highlights the need to develop research that contributes to the improvement of school coexistence. Although much research has been conducted on specific programmes, there are hardly any systematic reviews in the field of school coexistence (Tapullima-Mori et al., 2024). Some of the systematic reviews found are Sarasola and Ripoll (2019), focused on evaluating the effectiveness of anti-bullying programmes in Spain; Benítez et al. (2021), which focuses on the socio-emotional skills of school mediators; or Tapullima-Mori et al. (2024), which reviews the effectiveness of various programmes for the improvement of school coexistence. No systematic reviews have been found that specifically address the evaluation of student helper programmes. Taking into account this gap, this paper undertakes a systematised review of the literature aiming at obtaining an overview of the effects and limitations of the student helper programmes developed in Spain. Their results could be of interest both to schools and to guide future research. The study is based on the following research questions: 1) What is the overall evaluation, by students and teachers, of the student helper programmes researched in Spain?, 2) What are the evaluation differences between students and teachers?, 3) What specific benefits do participants report?, 4) What are the shortcomings and limitations of the programmes under study?, and 5) What proposals for improvement do the researchers suggest?

Method

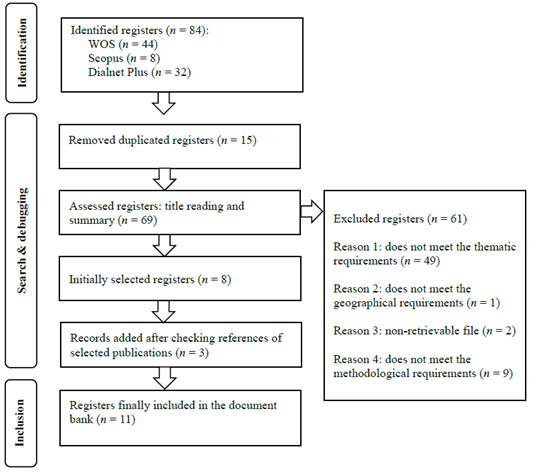

A systematised literature review was conducted following the SALSA protocol: Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, Analysis) and the PRISMA statement, as well as Codina’s (2020a) recommendations for reviews in the field of Human and Social Sciences.

The procedure followed in the four phases that make up the SALSA protocol is detailed below.

Search

The search process took place in June 2023 and was conducted by three expert researchers in the field of pedagogy and psychology. Searches were conducted in the databases with the highest impact, Web of Science and Scopus, in accordance with Codina’s recommendations (2020a). Following these author’s suggestions for systematised reviews in the Spanish context, the bibliographic portal Dialnet was also searched. The relevance of Dialnet in the field of education sciences was considered, as well as the fact that this bibliographic portal includes journals indexed in other prestigious databases such as Latindex.

The name of the programmes investigated was considered when selecting the keywords, which firstly led to the choice of the term “alumnado ayudante”. Likewise, other terms linked to these programmes in scientific publications on the subject were investigated and chosen by consensus: “ayuda entre iguales” and “apoyo entre iguales”. On the other hand, since the aim of the research was to learn about the effects and limitations of specific programmes, the key word “programme” was included.

Finally, the equivalent terms in English were searched for: “Peer support”, “peer helping peers”, “school”, and “program”. This led us to review publications by Helen Cowie, a pioneer in this line of research. Given the frequency with which peer support programmes have been used in the field of health sciences, the term “health” was used to exclude such programmes from the search.

Searches in Dialnet were conducted in Spanish, using the Dialnet Plus tool, applying the equations and geographical and subject filters specified in Table 1. Searches in Scopus and Web of Science were conducted in English, and the search equations were formed as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Search strategy.

| Database | Search equation |

|---|---|

| Dialnet Plus | “Peer support” AND “programme”. Filters applied: “journal article”; Dialnet subjects: “psychology and education”; Countries: “Spain” |

| “Student helper” AND “programme”. Filters applied: “journal article”; Dialnet subjects: “psychology and education”; Dialnet subsubjects: “education”, “Psychology and education: generalities”; Countries: “Spain” | |

| “Peer support”. Filters applied: “journal article”; Dialnet subjects: “psychology and education”; Dialnet subsubjects: “education”; Countries: “Spain” | |

| Scopus | (AFFILCOUNTRY (Spain) TITLE-ABS-KEY (“peer support” AND “school” AND “program” AND NOT “health”) SUBJAREA (psyc OR soci)) |

| (AFFILCOUNTRY (Spain) TITLE-ABS-KEY (“peer helping peers” AND “school” AND “program” AND NOT “health”) SUBJAREA (psyc OR soci)) | |

| Wos | (((((TS= (peer helping peers)) AND TS=(School)) AND TS=(program)) AND DT=(Article) AND CU=(Spain)) NOT ALL=(health)) AND PY= (2000-2023) |

| Web Of Science Categories (Refine): Education Educational Research / Psichology multidisciplinary |

Evaluation

The evaluation started by removing duplicate records. The researchers then independently read the titles and abstracts of the papers found, and applied the eligibility criteria specified in Table 2. As can be seen in the table, both pragmatic criteria (thematic, temporal, spatial, etc.) and quality criteria (type of publication and methodology used) were used.

Table 2. Eligibility criteria.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Theme | Student helper programme to improve coexistence in primary and/or secondary education. | Other programmes to improve coexistence. Other levels of the education system. |

| Type of publication | Articles published in indexed journals. Retrievable file. | Article published in a non-indexed or non-retrievable journal. Monographs, doctoral theses and other types of publication. |

| Methodology | Qualitative, quantitative or hybrid. Details research results. | Literature review. Does not report methodology or research results. |

| Geographical location | At least one Spanish educational establishment participates. | Only educational establishment located in other countries participate. |

| Time range | 2000 - June 2023 | Publications before 2000 or after June 2023 |

The application of the above-mentioned criteria allowed the first selection of articles to be made for inclusion in the databank. In cases where the eligibility of the article was in doubt, the researchers read the full text and made a joint decision. Once the first selection had been made, the bibliographic references of the selected articles were reviewed in order to detect other potentially eligible papers that might have been overlooked in the initial searches. To this end, we read the abstract of the references which, based on their title, appeared to meet the eligibility criteria, and included in the final databank those papers which did meet the criteria.

Analysis

We started by compiling the characteristics of the selected articles in an Excel table. Following Codina’s (2020b) recommendations, a structured format was used, collecting data on the following categories: authors of the work and year of publication, educational stage, autonomous community, type of study, research methodology, research design, and data collection techniques.

The results reported in each paper were then compiled, coding the information inductively using the system of categories and subcategories specified in Table 3, which was based on the research questions previously formulated.

Table 3. Coding system. Categories and subcategories for data analysis.

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Overall assessment | General perception |

| Advantages | |

| Assessment according to role | Student helpers |

| Students helped | |

| Specific effects | Application for help |

| Social and communication skills helpers | |

| Socio-emotional skills helped | |

| Conflict resolution | |

| Contradictory findings | |

| Moral connection of students | |

| Challenging bullying | |

| Moral connection of teachers | |

| Shortcomings and limitations | Selection procedure |

| Clash of expectations | |

| Lack of confidence | |

| Complex cases | |

| Programme dissemination | |

| Coordination | |

| Culture shock | |

| Proposals | Selection |

| Dissemination and communication | |

| Coordination | |

| Additional organisational measures |

Summary

The steps defined by Codina (2020b) were followed to write the final report, starting by reporting the results obtained in each phase of the PRISMA flow. This was followed by a descriptive synthesis to present the basic characteristics of the selected research, and finally a qualitative synthesis detailing the findings of the systematised review in relation to each research question.

Results

Selection of articles

As can be seen in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1), of the 84 records found, 15 were removed due to duplicity. The application of the eligibility criteria to the remaining 69 articles resulted in the selection of eight. A total of 52 papers were excluded on pragmatic grounds and nine on quality grounds. Taking into account the small size of the resulting database, the bibliographic references of each of the selected articles were reviewed. This process identified three additional articles that met the eligibility criteria and they were included in the final database, which consisted of 11 articles.

Descriptive summary

In terms of geographical area, the establishments located in Castilla y León (n = 6. 24%) and Madrid (n = 6. 24%) predominated. In the other Autonomous Communities, the number of investigations is lower: Castilla-La Mancha (n = 4.16%); Catalonia (n = 3, 12%); Galicia (n = 3, 12%); Andalusia (n = 2, 8%); Canary Islands (n = 1.4%).

As can be seen in Table 4, with reference to the level of education, most of the research was conducted in secondary education (n = 10). Only the work of Rey and Ortega (2001) also included primary school students. On the other hand, from a temporal point of view, four papers were published between 2000 and 2009, four between 2010 and 2019, and three after 2020.

Table 4. Descriptive summary of selected studies.

| Authors and year of publication | Educational stage | Autonomous community | Study type | Research method | Design of the research | Data collection techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrés, S., & Barrios, A. (2006) | Secondary education | Madrid | Empirical | Qualitative | Action-research | Discussion group |

| Andrés, S., & Gaymard, S. (2014) | Secondary education | Madrid | Empirical | Hybrid | Quasi-experimental with control group / case study | Questionnaire, focus group and in-depth interview |

| Avilés, J.M., & Petta, R. (2018) | Secondary education | Catalonia, Galicia, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Madrid | Empirical | Quantitative | Cross-sectional comparing centres with and without support equipment | Questionnaire |

| Avilés, J. M., & Tognetta, L. (2021) | Secondary education | Catalonia, Galicia, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Madrid | Empirical | Quantitative | Cross-sectional comparing centres with and without support equipment | Questionnaire |

| Avilés, J.M., Tognetta, L., & Petta, R. (2020) | Secondary education | Catalonia, Galicia, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Madrid | Empirical | Quantitative | Cross-sectional comparing centres with and without support equipment | Questionnaire |

| Avilés, J.M., Torres, N., & Vian, M.V. (2008) | Secondary education | Castilla y León | Empirical | Quantitative | Quasi-experimental with control group | Questionnaire |

| Avilés, J.M., Torres, N., & Vian, M.V. (2009) | Secondary education | Castilla y León | Empirical | Quantitative | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire |

| Barrio, C., Barrios, A., Granizo, L., Van der Meulen, K., Andrés, S., & Gutiérrez, H. (2011) | Secondary education | Madrid | Empirical | Qualitative | Case studies | Questionnaire including open-ended questions |

| Giménez-Gualdo, A. M., Galán, D., & Moraleda, A. (2021) | Secondary education | Canary Islands, Galicia, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Madrid | Empirical | Quantitative | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire |

| Martín, J. M., & Casas, J. A. (2019) | Secondary education | Andalusia | Empirical | Quantitative | Quasi-experimental with control group | Questionnaire |

| Rey, R., & Ortega, R. (2001) | Primary and Secondary education | Andalusia | Empirical | Qualitative | Action-research | Participant observation, interview and focus group |

Note.In the case of international research (Avilés & Tognetta, 2021; Avilés & Petta, 2018; Avilés et al., 2020; Barrio et al., 2011), only results from centres located in Spain are reported.

The table also shows that all the papers selected are empirical in nature. Most of them used quantitative methodology (n = 7), while a minority used qualitative (n = 3) or hybrid methodology (n = 1). Of the former, two used a quasi-experimental design, with pre-test and post-test measures and a control group. Five papers used a cross-sectional design, taking measurements at a single point in time. In the qualitative studies (n = 3), action-research designs (n = 2) stand out, using techniques such as participant observation, focus group discussions, and interviews. Only one paper opted for a case study design (n = 1), conducting a content analysis of a questionnaire with open-ended questions. Finally, the hybrid methodology study (n = 1) was based on a quasi-experimental design with a control group and was complemented with a case study, collecting data through a focus group and a semi-structured interview.

Qualitative summary

A summary of the analysis of the results reported in the papers reviewed follows below. The analysis was carried out on the basis of the five previously defined categories (see Table 3): overall assessment, assessment according to role, specific effects, shortcomings, and limitations, and proposals.

Regarding the first category, overall assessment, a generally positive perception of the student helper programme was found among members of the educational community (Avilés et al., 2008, 2009; Andrés & Gaymard, 2014; Barrio et al., 2011; Giménez-Gualdo et al., 2021; Rey & Ortega, 2001). Both teachers and students considered that the implementation of the programme had beneficial effects on school coexistence, and called for its continuous development.

As for the second category, assessment according to role, some differences were found in the perception of the programme according to the role played. In particular, Andrés and Barrios (2006), Avilés et al. (2008; 2009), and Rey and Ortega (2001) found that both student helpers and teachers had a more positive perception of the programme compared to the students receiving the service, who were more critical of its quality.

With regard to the third category, which focused on the evaluation of the specific effects of the programmes under analysis, three main types of effects were found: improvement in the social and communication skills of the student helper, improvement in the help-seeking and conflict resolution skills of the student helper, and increase in the moral connection of students and teachers in the face of bullying. However, it should be noted that the work also reported some paradoxical and contradictory effects. All these effects are set out in more detail below.

Firstly, an improvement in the social competence of student helpers was found. Thus, Martín and Casas (2019) found that the assistant students showed better scores in social competence and less involvement in bullying and cyberbullying roles, compared to the control group, as a result of their participation in the specific training for this role. In a similar vein, Giménez-Gualdo et al. (2021) reported an improvement in social, civic, language, and digital skills. In a similar vein, Barrio et al. (2011) and Rey and Ortega (2001) found improvements in the self-esteem and self-efficacy of student helpers.

Secondly, changes were found in students’ ability to ask for help and to resolve conflicts constructively. Several studies reported that helped students showed an increase in help-seeking behaviour (Andrés & Gaymard, 2014; Rey & Ortega, 2001), especially in situations of bullying victimisation (Avilés et al., 2008; Avilés & Petta, 2018). Other studies reported emotional relief, improved conflict resolution skills and increased feelings of protection among students (Barrio et al., 2011; Rey & Ortega, 2001). Similarly, Andrés and Gaymard (2014) found a decrease in disruptive behaviour in the classroom and Avilés et al. (2008) reported a significant decrease in the incidence of socially abusive behaviour. Despite the above, studies with a quasi-experimental design showed some divergent results. Therefore, Avilés et al. (2008) found the aforementioned decrease in social abuse but no significant differences in the incidence of physical and verbal abuse between the control and experimental groups. Andres and Gaymard (2014) reported a paradoxical effect, with an increase in the perception of conflict in the experimental group. In contrast, Martín and Casas (2021) found a decrease in aggression, victimisation, cyber-aggression, and cyber-victimisation scores.

Thirdly, specific effects of the student helper programme were found on the way bullying situations are perceived, favouring a greater moral sensitivity towards victims and improving the ability to offer and ask for help. Therefore, Avilés and Petta (2018) compared centres with and without support teams, finding significant differences between the two, with lower causal misattribution by victims, a more negative image of perpetrators, and greater ability of victims to ask for help in centres with support teams. Similarly, Avilés and Tognetta (2021) found that the student helper programme had a positive impact on moral development, promoting greater sensitivity towards victims and a discourse capable of questioning the legitimacy of bullying behaviour. In a similar vein, Martín and Casas (2019) found less involvement in bullying and cyberbullying roles, while Rey and Ortega (2001) observed greater moral sensitivity towards victims. As far as teachers are concerned, Avilés et al. (2021) found greater teacher moral connectedness and propensity to intervene in bullying in schools with student helpers, with the difference being statistically significant.

To return on the issue of the general categories of analysis of the results found in the research, the fourth category focused on the study of the shortcomings and limitations reported by participants in student helper programmes. In this sense, Andrés and Barrios (2006) identified some dysfunctionalities in the choice of student helpers, which led to the selection of some students with unsuitable attitudes, which had a negative impact on the performance of their duties. On the other hand, the evolution of the programmes revealed a confrontation between the high initial expectations of student helpers and the results achieved (Andrés & Barrios, 2006; Rey & Ortega, 2001). For their part, the student helpers recognised difficulties in intervening, especially in cases of aggression or rejection of the service (Andrés & Gaymard, 2014), and identified the distrust of the potentially helped students as a limiting factor (Rey & Ortega, 2001). As regards the link between student helpers and teaching staff, difficulties in communication, coordination, and low teacher involvement were identified in some cases (Andrés & Barrios, 2006; Rey & Ortega, 2001).

Finally, the last category of analysis of the results reported in the selected papers included the proposals for improvement formulated by the researchers. Therefore, Andrés and Barrios (2006) and Avilés et al. (2008) proposed improving the selection procedure for student helpers, giving more control to the teaching staff and favouring a prior process of reflection by the students on the ideal profile for the role. Andrés and Barrios (2006), Andrés and Gaymard (2014), Avilés et al. (2008), and Rey and Ortega (2001) proposed improving information dissemination mechanisms and opening new channels of communication so that students in need of help could overcome their fears. They also proposed to improve the collaboration between the assistantship team and the teaching staff by reviewing the support and supervision mechanisms provided to assistants. Given the complexity of the roles of student helpers, Rey and Ortega (2001) emphasised the importance of providing adequate psychological and strategic support from the guidance team. Finally, several studies recommended implementing, together with the student helper programme, other didactic and organisational measures aimed at eradicating bullying and improving coexistence (Avilés et al., 2008; Giménez-Gualdo et al., 2021), promoting a democratic culture of conflict resolution in schools (Andrés & Barrios, 2006).

Discussion

The results of the review show the scarcity of research on the effects of student helper programmes in Spanish schools, despite the fact that they have been implemented for twenty-five years and are relevant for the educational community (Luengo, 2017; Muslares, 2023; Torrego et al., 2021; Torrego et al., 2022), which highlights a certain dissociation between the life of schools and research. Furthermore, strong disparities within territories have been found, which could be related to the linking of the research teams, given that most of the work has been directed from the Universities of Valladolid and Alcalá de Henares. It would therefore be desirable to increase the number and geographical scope of research in order to obtain further evidence on the effectiveness of student helper programmes.

The assessed programmes are inspired by Cowie’s model (2011), requiring adequate planning and training of the participating teachers and students (Bueno et al., 2023), which implies a significant economic and time investment (Rey & Ortega, 2001). Likewise, the lack of acceptance by the educational community could generate fragility in the commitment of teachers and students, giving rise to the dysfunctionalities identified in some of the studies reviewed (Andrés & Barrios, 2006). All this suggests the need to provide schools with funding for the development of the programme (Bueno et al., 2023), training the teachers responsible and assigning them specific hours of dedication.

The studies reviewed confirm the positive impact of student helper programmes on improving coexistence, reporting improvements in the social and communication skills of student helpers (Andrés & Barrios, 2006; Andrés & Gaymard, 2014; Avilés et al, 2008 and 2009), improvements in helper students’ help-seeking and conflict resolution skills (Andrés & Gaymard, 2014; Barrio et al., 2011; Rey & Ortega, 2001) and greater moral sensitivity towards victims, along with collective questioning of bullying behaviour (Avilés & Petta, 2018; Avilés & Tognetta, 2021).

However, the students helped show a worse assessment of the programme, which suggests the need to improve the mechanisms of accompaniment and supervision (Andrés & Barrios, 2006; Avilés et al., 2009; Rey & Ortega, 2001). Reluctance towards the programme seems to be related to variables such as the weakness of the participatory culture and the rigidity of the school organisation (Andrés & Barrios, 2006; Sala et al., 2021), the lack of trust towards assistants, or the fear that they will not keep confidentiality. Future studies should explore these concerns in greater depth through qualitative designs, using their results to improve the effectiveness of programmes (Nieto-Bravo et al., 2023).

Quasi-experimental studies show that the programme alone does not reduce the frequency of bullying, which is consistent with previous findings in English-speaking countries (Cowie & Smith, 2013). However, there is an open debate on this issue (Gómez & Gaymard, 2014). Both the findings of some reviewed works (Avilés et al., 2009, 2020; Gómez & Gaymard, 2014; Rey & Ortega, 2001) and those of Cowie (2020) show a greater sensitivity and protection towards victims, as well as an improvement in coping skills, an issue that may be key to address current phenomena such as cyber-rumour (Bravo et al., 2022). On the other hand, the increase in the perception of conflict reported by Barrio et al. (2011) may not reflect an increase in violence, but rather a greater awareness and sensitivity of students to violence. Similarly, Menesini and Salmivalli (2017) stress the need for programmes to be developed over several years in order to achieve significant cultural transformations to reverse the bullying dynamics in schools. In contrast, most programmes analysed in this review were of one academic year’s duration, which could explain the lack of significant direct effects on the bullying variable. All the foregoing suggests that it would be advisable to extend the duration of the programmes and to carry out longitudinal studies that would allow us to know their long-term effects on the bullying variable.

On the other hand, it is considered necessary to investigate indirect indicators related to the minimisation of bullying. Some of them are reported in the works analysed: sense of security (Andrés & Gaymard, 2014), better emotional regulation (Martín & Casas, 2019), or emotional relief and better problem solving (Barrio et al., 2011). It is suggested that future research should better identify these changes during the programme by exploring the perspectives of children and adolescents through action research designs (Cowie & Fernandez, 2006).

The main limitations of this work are related to the geographical restrictions in the search and the exclusive selection of papers focused on evaluating the effects of student helper programmes. Research on other peer support systems and programmes commonly integrated in coexistence plans were excluded. This approach could introduce biases in the results, as suggested by Torrego et al. (2022), who advocate evaluating student helper programmes in conjunction with other organisational and curricular variables that influence the creation of a positive climate of coexistence. Despite these limitations, the results confirm the preventive value of student helper programmes, supporting the findings of previous research in other geographical contexts.

Conclusions

This review has found consistently reported benefits in the student helper programmes developed and researched in Spain. They are effective in integrating new students, encouraging demand for help and preventing, or correcting situations of social exclusion. Student helpers improve their social skills and self-confidence, becoming role models for their peers. In addition, a social support network is established to deal with situations of bullying, developing the educational community’s critical moral assessment of bullying and questioning the legitimacy of abuse. Teachers also play a more proactive role, which in previous studies has been related to more victims asking for help. However, the research found is limited, some of it being more than 15 years old. Therefore, it would be necessary to obtain further evidence to evaluate the effects of the student helper programme. In addition, the duration of the assessed programmes should be extended to several school years, and the effects on school coexistence in the medium and long term should be investigated.

The limitations and proposals for improvement found in the studies analysed indicate the advisability of optimising the implementation of the programme in schools, improving teacher training, the selection channels for assistants, the internal dissemination of the programme, and the processes of supervision and coordination by the teaching staff. On a practical level, this requires funding, better delineation of the programme coordination role, as well as a specific time allocation for this role. At the research level, action research designs could contribute to programme improvement by creating a continuous flow of information on the impact of improvements being made, the needs identified and the effects on participants.

texto en

texto en