Key Messages

1. There is certainty that a good quality diet implies a lower risk of developing sarcopenia.

Low fiber and vitamin C consumption were found to increase the risk of sarcopenia.

Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH), Mediterranean, ovolactovegetarian and Brazilian traditional diets were associated with a lower risk of sarcopenia.

Introduction

The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EGWSOP) defines sarcopenia as the syndrome characterized by the progressive and generalized loss of muscle mass and strength with a risk of adverse problems such as disability, poor quality of life and death1. Sarcopenia is a pathology with great implications for the daily life of the people affected, however, a single diagnostic criterion has not yet been established.

Various attempts have been made to standardize diagnostic criteria and cut-off points for diagnosing sarcopenia, most of them using combinations of measures of muscle mass, muscle strength, and gait speed. Among them, the most used definitions are the EGWSOP (2010) and the revised EGWSOP2 (2019)2. The EWGSOP recommends the use of the presence of both defining factors (loss of muscle mass and decrease in strength) for diagnosis1.

In accordance with the Petermann-Roche et al. systematic review, the prevalence of sarcopenia worldwide ranged from 10% to 27% in people 60 years old and over. In addition, the occurrence of severe sarcopenia in this age group fluctuated between 2% and 9%. These prevalence rates of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia varied considerably according to the classification and cut-off point used in each study2.

Parallelly, the relationship between sarcopenia and metabolic syndrome (MS) is interesting. Skeletal muscle is a major organ of insulin-induced glucose metabolism. In addition, loss of muscle mass is closely linked to insulin resistance and MS. In recent years, it has become clear that sarcopenia is closely related to MS, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), and cardiovascular disease. Skeletal muscle loss and accumulation of intramuscular fat are responsible for impaired muscle contractile function and metabolic abnormalities2. MS forms a cluster of metabolic dysregulations including insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia, central obesity, and hypertension. The pathogenesis of MS encompasses multiple genetic and acquired entities3. The prevalence of T2D patients who live in old age is increasing. This longer life expectancy directly results from improvements in treatment and follow-up appointments. Likewise, the number of patients with sarcopenia is increasing4. Muscle loss and intramuscular fat accumulation could be linked to MS through a complex interaction of factors including feeding behavior, physical activity, body fat, oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokines, insulin resistance and hormonal changes, and mitochondrial dysfunction5. There is a high proportion of MS in middle-aged and non-obese elderly people with sarcopenia, with MS being positively connected to sarcopenia in this age group6. MS and sarcopenia are also interrelated through insulin resistance, adipose tissue, chronic inflammation, vitamin D deficiency and other factors. Parallelly, a decrease in muscle mass and strength is associated with the development of MS, as well as physical inactivity has been linked to a major risk factor for both MS and sarcopenia7 as well as MS can be associated with sarcopenic obesity. Also, a study demonstrated that sarcopenia is independently associated with the risk of MS and might have a dose-response relationship8.

At the same time, another factor to consider is food intake, since it falls to about 25% between 40-70 years. Compared to younger people, older adults eat slower, have less sense of hunger, eat less at each meal, and snack less food between meals. This translates into a monotonous diet that can lead to inadequate nutrient intake. Thus, a vicious circle is created in which muscle mass and physical capacity are decreased9, the first one being one of the criteria for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Food patterns can be defined as the quantities, proportions, variety, or combination of different foods and drinks in diets, and the frequency with which they are habitually consumed10. One of the most studied pattern is the Mediterranean diet. This food pattern consists of antioxidants, anti-inflammatory micronutrients and n-3 fatty acids and is characterized by a high intake of monounsaturated fat and fiber11. Other food patterns examples are the Western diet and prudent pattern12. All the reviewed literature states that new researches are needed in the future to reach definitive conclusions on the most beneficial dietary pattern11-13.

Considering this, the aim of this systematic review was to explore the relationship between dietary patterns and the development of sarcopenia, focusing this objective on population with metabolic syndrome diagnostic criteria, due to its great relevance and the lack of in-depth literature reviews in this area.

Methodology

Design

This systematic review was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines (PRISMA)14 and was registered in PROSPERO with the number of register CRD42022369071.

Criteria for inclusion of studies

The inclusion criteria were defined as adult population (18 years and over), all sexes, diagnosed with MS or one of their components (obesity, dislypemia, hypertension and insulin resistance) and which contrast the relationship between sarcopenia and dietary pattern, with a cross-sectional, randomized controlled trials (RCT) or cohort design and published in English or Spanish language. Systematic reviews, congress publications, and populations with specific pathologies not related to MS as oncological pathologies and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease were defined as exclusion criteria.

Bibliographical search method

The strategy search used in the mentioned databases (Web of Science (all collections) and Scopus) can be found in supplementary material 1. The search was carried out in May 2023.

Selection of studies and data management

A first investigator (DCP) searched in the databases, downloaded the articles and eliminated the duplicated. After that, a first filtering phase was carried out by title and abstract by two independent researchers (DCP, PYG), both blinded to the opinions of the other. The discrepancies between DCP and PYG were contrasted by a third author (IDF). Having decided which articles were chosen, a complete reading of the articles was carried out by DCP, LBJ and AMD, following this, the read articles were selected for analysis. Afterwards, DCP and LBJ completed the data extraction about those articles: names of the authors, year of publication, place where the sample of the study that has been carried out was found, type of study, numerical data of the sample analyzed in each article (sample size, arithmetic average and age range, and distribution by sex), instrument used to collect information on diet, and conclusions. AMD, AFS and VMS participated in the cross-checked data extraction. The software used for the selection of studies was Excel®.

Assessment of methodological quality

A determination of the methodological quality and the risk of bias of the included studies was made following the Critical Appraisal Checklist of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)15 and the specific checklist for cross-sectional, cohort or RCT studies for each article according to their design.

The checklist for prevalence data uses nine items, each component was scored as “Yes”, “No”, “Unclear” or “Not applicable”. With 1-3 scores of “Yes”, the risk of bias rating was considered high, with 4-6 scores of “Yes” it was considered moderate and with “7-9” it was considered low. The JBI checklist for cohorts uses eleven criteria, and the JBI for RCT uses thirteen criteria, in these cases, with 1-4 ‘Yes’ scores the risk of bias rating was considered high, with 5-8 ‘Yes’ scores it was considered moderate and with 9-11 ‘Yes’ (9-13 for RCT) the score was of low risk. For inclusion in the review, articles were required to have a moderate or low-risk of bias score.

Synthesis methods

A qualitative synthesis of the data was carried out using a summary table of findings. It was completed according to the effect of nutritional patterns on sarcopenia, divided into three groups; the group of studies that use dietary survey, the group of articles that used Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and other one with the articles that used other methods to asses feeding. Specific effect measures were used for each one of the articles, these being mainly the Odds Ratio and the beta coefficients, accompanied by the p-value or the 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

Results

Study selection

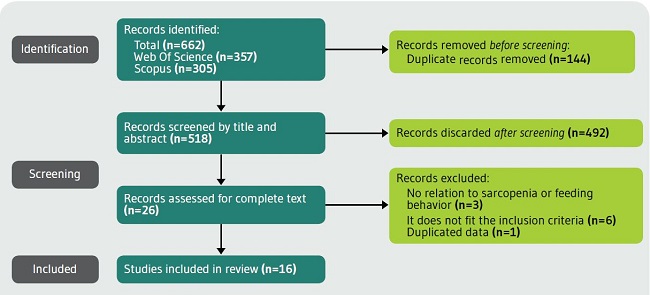

The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) shows the results of the process of revision. Also, the PRISMA checklist can be found as supplementary material 2. In total, 662 articles were found, 144 were eliminated because they were duplicated, and therefore 518 articles were analyzed by title. They were analyzed by title, abstract and complete text. The including articles were the following16-30. Articles excluded after full-text evaluation can be checked in supplementary material 3.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the chosen studies can be seen in Tables number 1-3. Twelve cross-sectional studies16-19,21,23-26,28,29, three cohort studies20,27,30 and one RCT22 were analyzed. The results were grouped according to the dietary data collection methods used. Four studies used a dietary survey (25%)19,21,25,30, in five the information collection method was the FFQ (31.2%)17,20,24,28,29 and seven used neither FFQ nor dietary survey (43.8%)16,18,22,23,26,27. The earliest published study included was from 201424. Seven of the studies were conducted in Asia (43.8%)17,19,23,27-29, five in Europe (31.2%)18,20,21,24,26 and four in America (25%)16,22,25,30. The total sample studied was 21453.

Analysis of risk of bias

After applying the JBI cohorts, cross-sectional or RCT studies checklists, respectively, no articles were removed due to high risk of bias. The obtained results were 1/3 moderate-risk and 2/3 low-risk for cohort studies, 1/1 low-risk in RCT, 11/12 low-risk and 1/12 moderate-risk for the cross-sectional studies. The complete analysis and evaluation items for each checklist can be found in supplementary material 4.

Results of individual studies

For the synthesis, the studies were divided into three categories: the articles that used the dietary survey, the articles that used the FFQ31 and the articles that used other different methods, such as the Brief Self-administered Diet History Questionnaire (BDHQ)32, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)16 and the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) test, which measures therapeutic adherence and its impact on the prevention of cardiovascular disease33.

Regarding the four articles that used the dietary survey (Table 1) it was observed that low fiber intake in individuals with MS21 and diabetic individuals who consumed less protein than recommended25 was related to a higher risk of developing sarcopenia, otherwise, diet and physical exercise in diabetic men30 and a diet that fulfill the recommendations about carbohydrate intake19 were associated with a lower risk of developing sarcopenia.

Table 1. Results of studies in which the data collection method is the dietary survey.

| First author, year of publication | Location | Type of study | Sample | Diet information collection instrument | Main results | Method of measuring sarcopenia | Diagnostic criteria for MS | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rahi et al. 201430 | Canada | C | N=156 (Mage: 74.6, SD=4.2) (39.7% women) | Three non consecutive 24 hours’ dietary recall. Then adapted score for C-HEI (Canadian healthy eating index) | After 3 years of follow up, diabetic males with Hight diet quality and stable physical activity were the group with best muscle strength maintaining, compared to the other groups with low diet quality or low physical activity (p=0.031). High quality diet includes high scores for fruits and vegetables intake, total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium, while there were no differences with the other groups in protein intake. These results were not conclusive in females. | Changes in muscle strength | Diabetes | Moderate risk |

| Montiel-Rojas et al. 202021 | Europe | CS | N=981 (Mage: 72, SD=4) (58% women) | 7-day dietary survey | Elder women with higher fiber intake than average had higher strength muscle index compared to those below (24.7 ±0.2% vs. 24.2 ±0.1%; p=0.011). While in men, the same association was only evident in those without MS. It suggests a beneficial impact of fiber intake on skeletal muscle mass in older adults. | DXA | All criteria | Low risk |

| Lee JH, et al.202119 | South Korea | CS | N=3828 (57.2% women) | 24 hours dietary survey | An increment of 100 calories of total and 1 increment for carbohydrate intake (g/kg/day), showed a protective power for the development of SO, with OR=0.95 (0.91-0.99) and OR=0.83 (0.74-0.94), respectively | DXA | Obesity | Low risk |

| Fanelli SM, et al. 202125 | EE. UU. | CS | N=2583, 31 years and older (40.4% women) | 24 hours dietary survey | Adults with diabetes had more frequency of physical limitations (mean: 68.0 in low protein intake (<0.8 g/kg/day) and 64.6 in normal protein intake (>0.8 g/kg/kg) than those with non-diabetes (mean: 73.8 in low protein intake and 72.6 in normal protein intake), and adults with diabetes who consumed less protein than recommended had further increased limitations | Grip strength and dynamometer | Diabetes | Low risk |

Explanation of the studies found which use a dietary survey (of various amounts of times) specifying their most important characteristics.

C: Cohort; CI: Confidence interval; CS: Cross-sectional; DXA: Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; Mage: Mean age; MS: Metabolic syndrome; SD: Standard deviation.

Regarding the FFQ, according to the studies that used it (Table 2), which were 5 of the total of 16 articles, daily red meat consumption20 (OR=0.25), a diet high in carbohydrates24 (OR=0.70), the ovolactovegetarian diet17, the DASH diet28 (OR=0.20) and the healthy beverage index29 (OR=0.20) were associated with a lower risk of developing sarcopenia.

Table 2. Results of studies in which the information collection method is the FFQ.

| First author, year of publication | Location | Type of study | Sample | Diet information collection instrument | Main results | Method of measuring sarcopenia | Diagnostic criteria for MS | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atkins, et al. 201424 | England | CS | N=4252 (Mage: 70.3) | FFQ | Eating a diet high in carbohydrates was related to reduced risk of sarcopenia in the elderly (OR=0.7; 95%CI: 0.5-1.0). | MAMC and FFMI | Insulin resistance | Low risk |

| Pereira da Silva, et al. 201820 | Portugal | C | N=521 (Mage: 67.51) (77.8% women) | FFQ | Daily red meat consumption was associated with a lower risk of developing sarcopenia (OR=0.25; 95%CI: 0.1-0.7; p=0.006) | Bioimpedance | All criteria | Moderate risk |

| Rasaei N, et al. 201928 | Iran | CS | N=301 (100% women) | FFQ | The association between DASH diet and SO was significantly negative (OR=0.20; 95%CI: 0.05-0.77; p=0.01), the risk of sarcopenia reduced by 80% | Bioimpedance | Obesity | Low risk |

| Chen,et al. 202117 | China | CS | N=3795 | FFQ | The ovolactovegetarian dietary pattern was a protective factor against the development of SO (95%CI: 0.60-0.97; p=0.02) | Bioimpedance | Obesity | Low risk |

| Rasaei N, et al. 202329 | Iran | CS | N=210 (100% women) | FFQ | There was a negative association between healthy beverage index and the risk of SO (OR=0.2; 95%CI: 0.35-1.01; p=0.05) | Bioimpedance | Obesity | Low risk |

Description of the studies found that use the FFQ specifying their most important characteristics.

C: Cohort; CI: Confidence interval; CS: Cross-sectional; FFMI: Fat-free mass index; FFQ: Food Frequency Questionnaire; OR: Odds ratio; Mage: Mean age; MAMC: Midarm muscle circumference; SO: Sarcopenic obesity.

Other data collection methods that made up the third block (Table 3) which were grouped 7 of the 16 articles analyzed are BDHQ, own validated scales and MEDAS.

Table 3. Results of studies that include various methods of collecting information, neither FFQ nor dietary survey.

| First author, year of publication | Location | Type of study | Sample | Diet information collection instrument | Main results | Method of measuring sarcopenia | Diagnostic criteria for MS | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abete, et al. 201918 | Spain | CS | N=1535 (Mage: 65.6) (48% women) | MEDAS | Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and vitamin C intake appeared as protective factors for the development of sarcopenia in individuals with metabolic syndrome. A statistically significant association was found between diabetes and high consumption of (p<0.05). | DXA | Overweight or obesity | Low risk |

| Cydne Perry, et al. 201916 | EE. UU. | CS | N=36 (Mage: 70.7) (58% women) | Resting energy expenditure (REE) | An increase in protein in the diet implies a decrease in grip strength (p<0.001) and, therefore, is related to a higher risk of developing sarcopenia. | Handgrip strength, skeletal muscle mass (bioimpedance) | Obesity | Low risk |

| Lee H, et al. 201919 | South Korea | CS | N=1802 (Mage: 55.72) (100% women) | Own validated survey | There was a correlation between middle-aged women’s SO and their dietary patterns. In unbalance diet pattern the risk of SO increases 1.715 times (95%IC: 1.050-2.801; p<0.05) | DXA | Obesity | Low risk |

| Takahashi, et al. 202023 | Japan | CS | N=351 (Mage: 66.6) (45.3% women) | BDHQ | In women, prevalence of sarcopenia was lower in the group with habitual miso soup consumption (18.8% vs. 42.3%; p=0.018). For adjusted regression model, habitual miso consumption was associated with a lower risk of sarcopenia (OR (95%CI) 0.2 (0.06-0.62)), while this wasn’t found among males. | Hand grip strength | Diabetes | Moderate risk |

| Aparecida Silveira, et al. 202022 | Brazil | RCT | N=111 (93.7% women) | DieTBra dietary intervention | DieTBra improves handgrip strength. Brazilian traditional diet has also been associated with a reduction in total body fat (p=0.041) and body weight (p=0.003) in severely obese individuals. | Hand grip strength | Obesity | Low risk |

| Kawano, et al. 202127 | Japan | C | N=362 (36.7% women) | BDHQ | Energy intake was associated with muscle mass loss in older participants (<65 years) (OR (95%CI, 0.94 (0.88-0.996)); p=0.037, while this was not found in younger participants. So insufficient energy intake is associated with muscle mass loss in older people with T2D. | Skeletal muscle index | Diabetes | Low risk |

| Marcos-Pardo, et al. 202126 | Europe | CS | N=629 (Mage: 56.4) (63% women) | MEDAS | A low protein diet was connected to an increased risk of developing sarcopenia. The consumption of more than one portion per day of red meat was a protective factor for sarcopenia development (OR=0.126-0.454; all p<0.01) | DXA | Obesity | Low risk |

Explanation of the studies found which use the rest of the data collection methods, specifying their most essential characteristics.

BDHQ: Brief Self-Administered Diet History Questionnaires; C: Cohort; CI: Confidence interval; CS: Cross-sectional; DASH: Dietary approaches to stop hypertension; DieTBra: Extra-virgin olive oil + a traditional Brazilian diet; FFMI: Fat-free mass index); FFQ: Food Frequency Questionnaire; Mage: Mean age; MAMC: Midarm muscle circumference; OR: Odds ratio; MEDAS: Mediterranean diet adherence screener; RCT: Randomized clinical trial; SO: Sarcopenic obesity; T2D: Type 2 Diabetes.

The BDHQ questionnaire confirmed that T2D diabetes patients, not having reached the daily protein requirements, increased the probability of developing sarcopenia27 (OR=0.94); and miso soup intake was confirmed as preventive of developing sarcopenia in women23 (OR=0.2).

Two articles based on MEDAS showed that the Mediterranean diet is related to an increase in grip strength26 (OR=0.126-0.454) and a protective factor against sarcopenia18.

The rest of the studies categorized the following as facilitators of the development of sarcopenia: diabetes and the consumption of more saturated fats and less vitamin C, a low amount of vitamins B6, C18, unbalanced diets19 and increased protein in the diet16. Brazilian traditional diet improves handgrip strength and has also been associated with a reduction in total body fat in severely obese individuals22.

Discusión

This systematic review aimed to explore the relationship between feeding patterns and the development of sarcopenia in patients with metabolic syndrome criteria.

According to our findings, specific dietary patterns such as the ovolactovegetarian, DASH, Mediterranean and DieTBra diets, as well as diets with high content in fiber and carbohydrates were associated with a reduced risk of developing sarcopenia, also, our results suggest that a good quality diet (a term used to quantify the general healthiness of a dietary pattern based on its components)34 reduces the risk of developing sarcopenia, an assertion that is reinforced by articles on malnutrition, especially proteo-energetic35, including unbalanced diets.

In relation to specific patterns, the ovolactovegetarian, and DASH diets were described as protectives against sarcopenia in this population17,28. These diets have a high daily vegetable and fruit content, and both foods have been associated with a reduced risk of sarcopenia in older adults36. Parallelly, Mediterranean diet was also associated with a lower risk of developing sarcopenia18. This pattern that has also previously been associated with less abdominal fat accumulation36 and its also associated in other studies with a low risk of development sarcopenia37,38 and with a “mioprotective” effect39. Also, the DieTBra was found as a protective diet against sarcopenia. This diet is characterised as a healthy dietary pattern based on the consumption of rice, beans, a small portion of lean meat, raw and cooked vegetables together with fresh fruits, bread and milk22.

Metabolic syndrome is characterised by the accumulation of intramuscular fat, and other components, leading to the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways5,40. The above diets include a large number of anti-inflammatory nutrients that could be beneficial for this population, in turn reducing the risk of sarcopenia as an inverse association has been observed between adherence to anti-inflammatory nutrient-based dietary patterns and odds of sarcopenia and low muscle strength41.

Regarding specific foods, low-fiber diets21 were associated with an increased risk of sarcopenia. High fiber intake, also present in the DASH diet, has also been linked to a reduction in inflammation due to its action on glucose absorption and microflora42. Low vitamin C intake was also associated with an increased risk of sarcopenia18. Patients with MetS have been reported to consume less vitamin C, which also contributes to regulating low-grade inflammatory processes43.

In the case of protein intake, it was observed that some articles confirm that low protein intake was related to an increased risk of sarcopenia4,25,26 being found the consumption of red meat a protective factor against sarcopenia20,26 and this same result has been observed by other authors in older adults44. However, Cydne Perry et al.16 observed contrary results, observing that high protein intake led to a greater risk of developing sarcopenia. This disparity can best be understood as described by Dhillon R and Hasni S45: “A decrease in the body’s ability to synthesize protein, coupled with an inadequate intake of calories and/or protein to sustain muscle mass, is common in sarcopenia”. This raises doubts as to whether the problem is intake or the body’s capacity for synthesis.

Continuing with the macronutrients, carbohydrates stand out. Its low consumption is the one that best adapts as a predictor of the development of sarcopenia among all the macronutrients. It has also been seen that a diet high in carbohydrates intake was related to a reduced risk of sarcopenia in the elderly population19,24 as carbohydrates are the first source of energy for the muscles41. Also, total energy intake was associated with muscle mass loss in older people but was not in young individuals27.

Finally, Takahashi et al.23 revealed that miso soup, was found also as a protective food against sarcopenia. It includes vitamins, minerals, vegetable proteins, microorganisms, salts, carbohydrates, and fat.

The results of this study must be taken with caution since it has a series of limitations. Heterogeneous results were observed in the influence of diet and the occurrence of sarcopenia in patients with metabolic syndrome since diet is a very broad variable. This is due to the fact that most of the included studies analyze specifically, whether it is a dietary pattern or a specific macronutrient, and this in addition to the wide variety in the collection of information, as each author used a scale or a method of collecting information about a different eating pattern. That makes it difficult to obtain a specific conclusion now that macro and micronutrients can be specifically studied within the diet, dietary patterns for instance the Mediterranean and ovolactovegetarian or the intake of certain foods. Moreover, this heterogeneity prevented carried out a meta-analysis. However, having separated it by charts in the synthesis according to the collection method, it is expected that this limitation is controlled. Since systematic reviews were not included as inclusion criteria, relevant information may have been lost.

Regarding the strengths, a large number of articles have been analyzed in this review. Together with a unification of the diagnostic criteria and an updated and novel review of the evidence on this topic, especially focused on patients with metabolic syndrome criteria, which may be key for the implementation of guidelines in clinical practice.

In this way, the line of work in the future is justified with the general population that is increasingly getting older. In addition, it could be interesting to carry out work in which to determine the relationship between dietary patterns, but in a standardized way, using the same tool in each group of study, which would lead to greater clarity when extracting the results of the study. We also highlight the value of developing a decalogue or similar guidelines that severe as a dietary guide for patients at risk to improve their diet and prevent sarcopenia. Future research should be deepened to determine the role of eating patterns, isolated nutrients and specific foods to provide advances in this field.

Conclusions

In sum, there is evidence that a good quality diet implies a lower risk of developing sarcopenia in people with metabolic syndrome criteria. Low fiber and vitamin C consumption were associated with an increase of the risk of sarcopenia. Ovolactovegetarian, Mediterranean, DASH and DieTBra diets were found as protective against sarcopenia. Also, diets that fulfil the recommendation about carbohydrates intake, daily red meat consumption and miso soup were associated with a lower risk of sarcopenia too. No solid conclusions were found regarding high or low protein intake and its relationship with sarcopenia. It is of particular interest that appropriate dietary patterns are followed in the metabolic syndrome population for the prevention and improvement of sarcopenia.