Introduction

Many people claim to be experts in nutrition yet have very limited knowledge and do not offer protection to the public. Providing knowledge of nutrition is realised through true nutrition education. Educational programs for nutrition have a direct impact on the knowledge of nutrition and nutritional behaviours 1.

A dietician is a health professional who has a Bachelor's degree specialising in foods and nutrition, as well as a period of practical training in a hospital and a community setting. It takes at least four years of full-time study at a university to qualify as a dietician. Many dieticians further their knowledge by pursuing a Master's or Doctoral degree. Dieticians apply the science of nutrition to promote health, treat and prevent malnutrition and provide therapeutic dietary guidelines for patients, clients and the public in health and illness.

The majority work in the treatment and prevention of disease in hospitals, health maintenance organizations, private practice, or other health care facilities. In addition, a large number of dieticians continue to work in community and public health settings and academia and research. A growing number of dieticians work in the food and nutrition industry, in business, sports nutrition, and corporate wellness programs 2.

Understanding and applying nutrition knowledge and skills to all aspects of health care are extremely important, and all health care professions need basic training to effectively assess dietary intake and provide appropriate guidance, counselling, and treatment to their patients 3. Despite this, it is widely recognized that most health care professionals receive little nutrition training and are ill-equipped to assess their patients’ diets and nutritional status as well as provide nutrition counselling 4,5. The quantity of formalized nutrition education is shrinking in curricula of health professions (physicians, nurses and pharmacists), including dietitians 6. There must be consensus among the healthcare professions as to the depth of nutrition education and the stage of training at which these integrations should occur. In view of the importance of assessing nutrition knowledge in nutrition practitioners and nutrition education programmes at university, it appears essential to evaluate gaps in nutrition education and training within individual health professions.

Objective

Currently, there is an absence of research evaluating the nutrition knowledge of students undertaking nutrition and dietetic studies and dietician practitioners in Spain. The present research aims to describe the level of general nutrition knowledge in students enrolled in the B.Sc. degree in Human Nutrition and Dietetics and already graduated dieticians, and compare knowledge status across different occupations. The secondary aim was to investigate the variation in knowledge among the cohort according to academic year, years of experience and area of expertise.

Material and Methods

Study population

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted. Food and Nutritional Sciences students or dieticians in Spain, aged 17 to 65 years, of any gender, were eligible to participate in this study. Other health-related or none health-related professionals were excluded.

Procedures

An online anonymous survey was sent, during September and October 2018, to a random sample of Food and Nutritional Sciences students and dieticians to assess basic nutritional knowledge, self-reported attitudes and practices. The survey was only intended for dieticians in Spain or who practice in Spain. The application of the questionnaire was supervised and processed by trained health professionals and researchers. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data collection

For the collection of research data, permission from the participants was obtained. The subjects were requested to participate in the study on a voluntary basis and were informed that their information would remain confidential and the data would only be used for research purposes. Questionnaire items were developed by a registered dietician and a researcher in the field of nutrition. The survey included 7 demographic and 16 survey statements.

Demographic Information Form

This form comprised 7 relevant socio-demographic questions such as the gender and age of the participant, whether he/she is a Food and Nutritional Science student or a graduated dietician, the academic year (if a student), the graduation year, years of practice and area of expertise (if dietician). These were included in the survey to collect a general description of the participants and to run statistical analysis according to these groups.

Nutritional knowledge

A total of 16 items were developed to cover four areas of nutrition knowledge: personal beliefs and dietary aspects (section A, 5 items), eating recommendations (section B, 3 items), degrees of evidence (section C, 5 items) and studies funding (section D, 3 items). Different types of question styles were used including open-ended, multiple-choice and agree or disagree. Five items on personal beliefs (e.g. ‘Do you think that university contributes an outdated knowledge?’) and diet-related opinions (e.g. the use of additives; benefits of a gluten-free diet) were assessed with multiple-choice questions. A ‘NR/DK’ option was also available for one of the items, as it removed pressure from participants and also ensured answers are not randomly assigned. Three multiple-choice items were included to assess eating recommendations (e.g. ‘Is eating five times a day recommended for a healthy diet?’; How many eating times would you recommend to a patient?; Which is the recommended proportion of macronutrients to be met daily?). The last item was assessed with a short open-ended question within the multiple-choice, to leave space for possible alternatives. A series of five items assessed knowledge of degrees of evidence (e.g. ‘Which type of study provides the greatest degree of evidence?’). Three items were developed regarding the financing of studies. One of the items was presented as ‘agree or disagree’ question type; the other two were presented as multiple-choice question type. A ‘none of the answers’ option was also available for one of the two last items, to again removed pressure from participants.

Statistics

Data were coded numerically and statistically analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 24.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY: USA). A descriptive analysis was performed for the socio-demographic variables. Within-group differences for ‘occupation’, ‘academic year’, ‘years of experience’ and ‘area of expertise’ were assessed with one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test. P-values were considered statistically significant if p<0.05.

Results

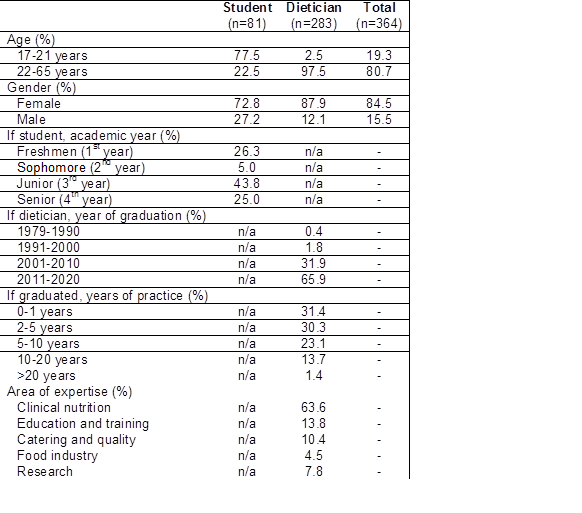

A sample of 364 participants, of both genders, was eligible to participate and took the survey in 2018. Subjects were aged 17 to 62 years, mean age 27.9 ± 7.26. n=81 (22.3%) were students and n=283 (77.7%) were dieticians. All survey responses were complete, but there were n=23 withdraws from the data due to failure to comply with the inclusion criteria. Baseline socio-demographic results are displayed in percentages in Table 1.

Female representation of the collective was predominant in the sample. Most of the students at university were in their 3rd and 4th year, and most of the dieticians graduated in the last 10 years. Already graduated dieticians had mostly 1 to 5 years of experience. Varieties of areas of expertise were represented in the study, among which, clinical nutrition and educations and training dominated the group.

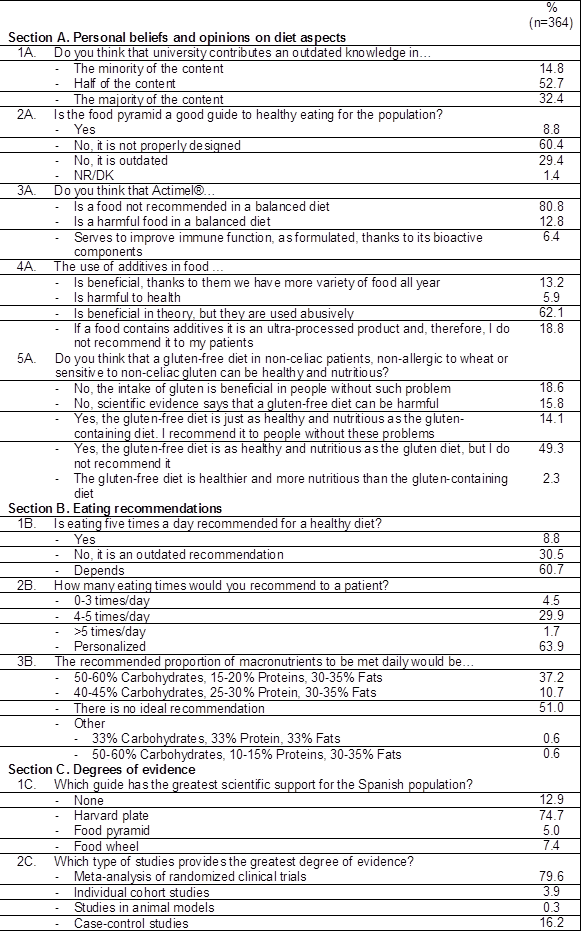

The items that contribute to subjects’ general nutritional knowledge are displayed inTable 2, divided in the aforementioned four areas: personal beliefs and dietary aspects (section A), eating recommendations (section B), degrees of evidence (section C) and studies funding (section D).

Table 2 Percentage of response to each survey question, sorted in sections A to D.

Results expressed as percentages (%) unless otherwise stated.

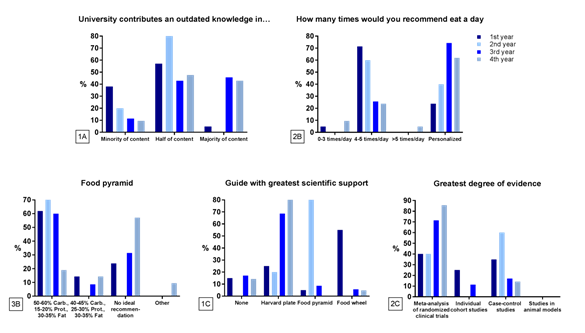

To further elucidate the differences between responses to personal beliefs and dietary aspects (section A), eating recommendations (section B), degrees of evidence (section C) and studies funding (section D) items, subjects were divided into different groups for analysis, according to discipline, academic year, years of experience and area of expertise. Only items which resulted in statistically significant differences in each group were represented (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Dieticians suggested there is no ideal distribution of macronutrients along the day, but if they had to dictate a distribution it would be 50-60% carbohydrates, 15-20% proteins and 30-35% fats. On the other hand, students believed that a distribution of 50-60% carbohydrates, 15-20% proteins and 30-35% fats would be ideal. Only students proposed alternative distributions such as 33% carbohydrates, 33% protein and 33% fats or 50-60% carbohydrates, 10-15% proteins and 30-35% fats (Figure 1, 3B). Harvard plate was considered the guide with the greatest scientific support for the Spanish population by dieticians, followed closely by students. However, the food pyramid was the least commended to be the best guide (Figure 1, 1C). Both groups agreed on meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials to be the study type which provides the greatest degree of evidence; although some students supported case-control studies and only dietician mentioned the studies in animal models (Figure 1, 2C). A 44.5% of dieticians asserted that studies financed by the industry have no credibility or reliability, while 30.4% believes industry may finance studies as long as they declare the conflict of interest and their results are objective and reproducible. The remaining 25.1% did not opt for any of the two previous options. Students followed the same trend (Figure 1, 2D).

Figure 1 Statistically significant differences in responses to items 3B (p=0.007), 1C (p=0.012), 2C (p=0.016) and 2D (p=0.023), according to occupation.

As years pass at university, the number of students who believe university contributes an outdated knowledge in the majority of the content increases (Figure 2, 1A). With regards to how many times would the participants recommend eat per day, freshmen and sophomore students support eating 4-5 times/day, while juniors and seniors would personalize the recommendation depending on the patient (Figure 2, 2B). 4th year students suggested there is no ideal distribution of macronutrients along the day. However, 1st, 2nd and 3rd year students believed that a distribution of 50-60% carbohydrates, 15-20% proteins and 30-35% fats would be the one to follow. Only students in 4th year proposed other distributions (Figure 2, 3B). Harvard plate was considered the guide with the greatest scientific support for the Spanish population by 3rd and 4th year students. However, 1st and 2nd year students recognise the food wheal and the food pyramid, respectively, the best guide (Figure 2, 1C). Juniors and seniors agreed that meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials are the studies which provides the greatest degree of evidence. None of the students considered studies in animal models having a good degree of evidence (Figure 2, 2C).

Figure 2 Statistically significant differences in responses to items 1A (p=0.001), 2B (p=0.002), 3B (p<0.001), 1C (p<0.001) and 2C (p=0.029), according to academic year.

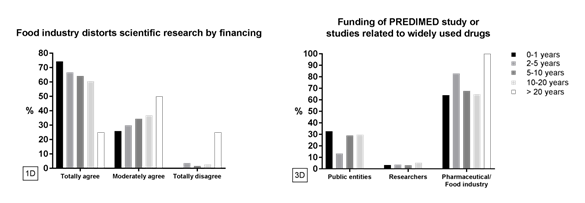

Statistically significant differences could only be seen for items 1D and 3D ("Do you think food industry distorts scientific research by financing?" and "Who do you think has funded the PREDIMED study or studies related to widely used drugs?") when analysing the data by years of experience. The most experienced dieticians (>20 years’ experience) agreed that pharmaceutical industry and food industry with high conflict of interest were the source of funding of PREDIMED study or studies related to Diazepam, Sintrom and Omeprazole (Figure 3, 3D), but generally did not think the funding distorts the research (Figure 3, 1D); while the less experienced dieticians (<10 years’ experience) debated between public entities and pharmaceutical or food industry (Figure 3, 3D) and opined that the food industry distorts results by financing.

Fig. 3 Statistically significant differences in responses to item 1D (p=0.04) and 3D (p=0.025), according to years of experience.

According to area of expertise, dieticians committed to food industry strongly believed the ideal proportion of macronutrients to be met daily would be 50-60% carbohydrates, 15-20% proteins and 30-35% fats. On the contrary, dieticians dedicated to clinical nutrition, education and training and catering and quality suggested there is no ideal recommendation. Researchers were divided between the latter options (Figure 4, 3B). Most of the dieticians belonging to the five different areas of expertise totally agreed that food industry distorts scientific research by financing, except for researchers who moderately agreed or totally disagreed, and educators who moderately agreed (Figure 4, 1D).

Discussion

This study has highlighted there are inconsistencies in the dietary knowledge and attitudes towards dietary advice, the degrees of evidence and opinions regarding funding of studies between human nutrition practitioners.

Such conflicts, in addition to directly affecting health through the use of wrong messages, can have a detrimental effect on the behaviour, motivation and attitudes of an individual. It is essential that the edu cation and training of health professionals, including nutritionists, has a consistent approach to ensure reliable dietary advice is given 3.

It may be speculated that these conflicts seem to be largely due to inadequate training and education of students, the future profes sionals; indeed, there is growing evidence that the nutrition content of health professionals courses is inadequate 7. In fact, 31.8% of the studied population conceded the majority of the content taught by Universities is outdated, followed by a 53.2% who considers half of the content is obsolete. Technology has made the library obsolete and what society needs from education is shifting. Universities should adapt to changing needs of the workplace, and provide future professionals the required best setting for the combination of updated practical and academic study.

When analyzing in detail the results of the survey, it is observed how most of the respondents consider that the food pyramid is poorly designed or obsolete. A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition8 shows the pyramid and other official guidelines are most likely obsolete. The Food Guide Pyramid is an American icon. At the base are breads, cereal and pasta, up to 11 servings a day. Vegetables and fruits are next, with two-to-five servings a day. As the pyramid narrows, it suggests eating fewer dairy products, eggs and meat servings. At the tip are fats and sweets, to be used sparingly. The pyramid's problem might be that it assumes that only fat calories can make people gain weight, but the reality is, it's too many calories from whatever the source they are intake.

It should be taken into account there is a diverse range of healthy eating guides currently existing across different countries (Healthy Eating Pyramid in Australia 9, China’s pagoda 10, Canada’s rainbow 11, France’s staircase 12, Japan’s spinning top 13, Belgium’s inverted triangle 14) and all of them are adjusted to the gastronomy and culture of each specific country. Dietary guidelines for the Spanish population are summarised graphically in a pyramid model 15. However, a high percentage of participants considered the Harvard plate (Healthy Eating Plate) as the guide with greatest scientific support for the Spanish population, which is indeed gaining more adepts as it is certainly based more on science and research basis. Nevertheless, Healthy Eating Plate was designed by experts at Harvard School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School for the US population, as an alternative to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s MyPlate 16, and should not be taken as a reference for the Spanish population.

Actimel® was not considered a recommendable product in a balanced diet by most of the respondents; however, the marketing company included in the formulation of the product an additional component, vitamin B6. This endorsed the use of the EFSA health claim for vitamin B6, which indicates that vitamin B6 contributes to normal functioning of the nervous system. However, claims may have a ‘halo’ effect, influencing consumer perceptions of foods and increasing consumption when unnecessary 17.

Regarding the use of additives in food, the majority considered is beneficial in theory, but they are used abusively, closely followed by those who believe if a food contains additives it is an ultra-processed product. This concept was devised by a Brazilian nutrition researcher Carlos Monteiro 18, used to refer to the processing of substances derived from foods (e.g. baking, hydrogenation). They generally include a large number of additives such aspreservatives,sweeteners, sensory enhancers,colorants, flavours and processing aids, but little or nowhole food. Ultra-processing creates attractive, hyper-palatable, cheap, read to eat food products that are characteristically energy-dense, fatty, sugary or salty and generally obesogenic. Therefore, participants would not recommend the use or intake of additives to their patients. Neither would they recommend a gluten-free diet in non-celiac, non-allergic to wheat or sensitive to non-celiac gluten patients, although considering the gluten-free diet as healthy and nutritious as the gluten-containing diet. This taught results as contradictory as the gluten-free diet itself, as some evidence indicates that there are significant drawbacks to following the gluten-free diet. Even so, people without diagnosed gluten issues are trying the diet to assist in the management of other medical issues without much evidence 19. In fact, 2% of the respondents sustained the gluten-free diet is healthier and more nutritious than the gluten-containing diet.

More long-term studies to determine the optimal number of times a day to eat are needed. The American Heart Association concludes that there is not enough evidence to prove that changing the number of times we eat has a significant impact on weight or cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure, triglycerides, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. The key is not the number of times we eat, but rather what we choose to eat 20. Therefore, the vast majority of the ones polled affirmed that eating five times a day is recommended for a healthy diet depending on the case and that they would personalize the eating times of their patients, being congruent in their responses. However, on the contrary, 30% marked 4-5 times/day as the recommended eating times, but at the same time considered that recommendation as outdated, being incongruent with their responses. This suggests that self-administered questionnaires are likely to affect the quality of the data collected and have biasing influences 21.

In regard to the recommended proportion of macronutrients to be met daily, half of the survey respondents consider there is no ideal recommendation, closely followed by a believe that 50-60% carbohydrates, 15-20% proteins and 30-35% fats should be the daily macronutrient distribution. It is surprising that there is no consensus among professionals for this formulated question, and that practically 50% think in one way and 50% in another, that is, some believe in a recommendation of specific macronutrients and others do not. In any case, the European Food and Safety Authority (EFSA) proposed, in 2010, that the total intake of carbohydrates should range between 45% to 60% of the total energy intake (25 g of which should be fiber) 22. However, this recommendation has been questioned. The recommended dietary allowance for digestible proteins for adults is 10-35% of energy intake 23, or a minimum of 0.83 g/kg body weight based on the EFSA 2012 position statement 24. For healthy individuals, the EFSA also proposed in 2010 that lipids should be in the range of 20-35%, and that the replacement of SFA by MUFAs and PUFAs was considered to be crucial 25. It is clear that an individualized approach would require clinical experience and the consideration of relevant clinical parameters. Not less surprising is that, as scientific branch health professionals, 20% of the subjects are unaware of the degree of evidence a study provides.

The practice of evidence-based medicine seeks to use individual expertise along with the best available clinical evidence. In this regard, many health professionals in this study struggled answering about the best available scientific evidence of the recommendations they give to a patient. The concepts of level of evidence and grade of recommendation are essential to be well established in health practitioners, as the level of the evidence and the strength of the recommendation indicate the extent to which it can be trusted that implementing a recommendation will bring more benefits than risks. As to the funding of big studies, such as PREDIMED study or studies related to Diazepam, Sintrom and Omeprazole, and the distortion of the results, respondents were again incongruent in their answers. A high percentage agreed that pharmaceutical industry and food industry funding the studies have high conflict of interest, but simultaneously considered the results are objective. Besides, while considering PREDIMED study and others of great evidence, they also considered distorted by the financing of the industry.

Regarding how much evidence the beneficial effect of alcohol on cardiovascular disease has, there was a very equitable distribution among participant’s beliefs. However, alcohol seems to exhibit a cardioprotective effect 30 and there are many meta-analysis supporting this body of evidence 26-29.

Conclusion

This study documents concerns about the deficiency of general nutritional knowledge of Human Nutrition and Dietetic students and already graduated dieticians. It identifies that significant conflicts exist not only in dietary advice aspects but also in knowledge regarding scientific degrees of evidence. The reasons for the lack of consistency are multifactorial, but certainly include considerable gaps of adequate nutrition education. Elimination of this conflict is crucial if the health of the nation is to be improved. There is great potential for the nutrition content at universities to be further developed.

Study limitations

There were a number of limitations to the present study. Although the demographic characteristics of participants were representative, the response rate to the distributed surveys was not the greatest. Therefore, it is possible that the results do not accurately reflect the knowledge of the larger group of dieticians. The tool employed to evaluate nutrition knowledge was designed to represent some of the general knowledge assumed to be required for a minimum good practise of the profession. Thus, this research could not evaluate the application of professional knowledge. Lastly, the cross-sectional design is vulnerable both to random and systematic measurement errors and cannot determine the changes in each individual’s nutrition knowledge.