INTRODUCTION

Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (RTS) is a genetic disorder, passed down through families in an autosomal dominant fashion, originated from abnormalities in CREBBP (locus cromosoma 16p13.3) or EP300 (locus cromosoma 22q13.2) genes. RTS estimated prevalence varies from 1:100.000 to 1:300.000 births, with no observed differences related to gender. RTS is clinically characterised by distinctive facial features, broad and radially deviated thumbs and first toes, short stature, microcephaly and moderate to severe intellectual disability. Additional features include ocular abnormalities, hearing loss, respiratory difficulties, heart and kidney congenital defects, cryptorchidism, feeding problems, recurrent infections, severe constipation, odontostomatology disorders and a higher risk of malignancies [1, 2].

Odontostomatology disorders in patients with RTS are quite frequent but not so well-known by odontology and paediatrics professionals due to the syndrome being extremely rare. In 1990 Hennekam et al. [3] underwent the largest case study and compared it with the existing literature. In their work they observed in the jaws a high frequency of two or more talon cusps in patients with RTS. This finding, rarely appearing in the healthy population or in relation to other syndromes, strongly helped in the field of dysmorphology to link the presence of talon cups with the diagnosis in suspected RTS patients.

In this work we describe the odontostomatologic findings in a child patient with RTS and we update the existing literature.

CLINICAL CASE

A 5-year-old child diagnosed with RTS after a genetic study, visits the dental practice in Health Center Seminario in Saragossa, Spain, for her first OD evaluation. The initial OD exploration is quite limited due to the reticence of the patient to be examined. Nevertheless, we observe first-phase mixed dentition with deciduous teeth cohabiting with the first permanent molar. We highlight the presence of tartar in the lower incisors, both in the buccal/labial (Figure 1) and the lingual (Figure 2) regions. There is no presence of cavities. We also observe macroglossia and lingual interposition in the anterior area (Figure 3) that produced anterior open bite. The patient's mother refers to her habit to stick out her tongue, especially during the night that we link with the latter OD manifestation.

Figure 1. Tartar in the lower incisors in first-phase mixed dentition with deciduous teeth cohabiting with the first permanent molar.

Figure 2. Tartar in the lower incisors in the buccal/labial zone in first-phase mixed dentition with deciduous teeth cohabiting with the first permanent molar. Importar tabla

The patient is derived for therapy to the oral and dental unit for patients with special needs in Hospital San Juan de Dios in Saragossa, due to the special requirement to sedate these patients for OD assistance in order to evaluate and treat them appropriately. Eliminating the lingual interposition habit is desirable, but given the special circumstances of the patient, the use of some equipment that prevents this habit should be considered. This could help eliminating the presence of anterior open bite. Similarly, dental prophylaxis is advisable to sanitize the oral cavity and allow a more detailed inspection of the dental pieces. Once sedated, a professional cleaning was performed, removing all the tartar from the oral cavity. The occlusion is kept under surveillance.

DISCUSSION

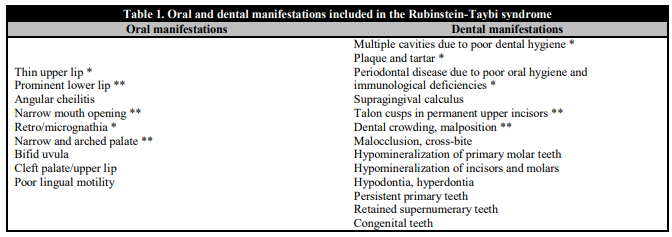

RTS can be linked with a variety of oral and dental disorders. In Table 1 we describe the OD manifestations, more frequently described in recent literature for the last 15 years [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. The patient of this clinical case echibited the following oral manifestations: prominent lower lip, narrow mouth opening, narrow and arched palate, history of angular cheilitis, micrognathia and poor lingual motility. On the other hand, the dental manifestations included the presence of plaque and tartar, bleeding from gingival areas due to poor dental prophylaxis, and malocclusion in the form of an anterior open bite. All of these OD findings are observed in 40-60% of patients diagnosed with RTS.

Table 1. Oral and dental manifestations included in the Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome

* Present in more than 40% of the patients. ** Present in more than 60% of the patients.

Dental treatments for pathologies in children with RTS, given the complexity and lack of cooperation due to their age and mental disability often require a variety of sedation techniques including in some cases, general anesthesia. Previous reports show that, due to the anatomical characteristics of the oral cavities of children with RTS and their frequent gastroesophageal reflux, the process of intubation can be difficult and present risks of aspiration in the tracheobronchial tract [15].

All in all, pediatric patients with RTS frequently exhibit certain OD disorders and so we consider essential to raise awareness and educate professionals of the importance of referring them to the pediatric dentist from 1 year of age and performing check-ups every 6 months. Dental treatment can often become difficult due to the need of different sedation techniques. We recommend collaboration with anesthesiologists in order to carry out a safe and effective treatment.