INTRODUCTION

Corynebacterium spp. are aerobic, gram-positive rods, which are in normal skin flora bacteria in humans. It is also abundant in soils and waters. They can form biofilms and be found in the hospital environment, surfaces, and medical equipments [1]. They are frequently isolated in cultures, but they were previously often considered contaminants. However, they can sometimes cause nosocomial infections in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients [2]. Factors such as advanced age, frailty, chronic lung disease, immunosuppression, prolonged hospitalization, use of medical instruments are the reported risk factors. Corynebacterium spp. can be difficult to manage due to increased antibiotic resistance [1, 2].

Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIEDs) were discovered in the early 1960s, and the number of patients which CIED applied increasing year-by-year [3]. The total number of CIED installed per 1,000,000 people per year is 247, and with the aging of the population [4, 5]. It is predicted that these devices will be installed more and more in our country as in the world over the years [3].

CIED infections could be observed as pocket infections, occult bacteremia, and infective endocarditis (IE) (wire or cap). Pocket infections are the most common (60%) and local inflammatory changes in the pocket area (pain, redness, swelling, warmth, discharge or decomposition of the overlying skin) could be observed [4, 5]. Sometimes, pocket infection could be accompanied by bacteremia. However, bacteraemia could be observed without signs of infection in the pocket area [3, 4, 5]. IE is the third clinical presentation, being observed in 10-23% of all CIED infections [3]. The prevalence of CIED infections in CIED recipients is nearly 5% within 3.5 years post implantation [6]. The rate of those associated with CIED among all IE cases is around 10% in our country and in the world [3]. Corynebacterium spp. with demonstrated biofilm forming ability has been associated with cardiac device-associated infective endocarditis and there are few cases in the literature [6, 7, 8].

Hereby, we report a case report of a 55-year old man with Corynebacterium spp. cardiac device-related infective endocarditis. With this rare case, we aimed to contribute to the literature and to present that blood culture growth, which is often overlooked, can be encountered with a complicated CIED infection.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old man presented to our hospital with a 20-day history of fever. He denied other symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain, abdominal pain, cough, diarrhea, or dysuria. His past medical history was limited to having hypertension, congestive heart failure, history of coronary artery bypass grafting surgery 2 years ago and placement of a biventricular pacemaker 6 months ago. On his clinical examination, vital signs were as follows: his temperature was 39°C, blood pressure 136/84 mm/Hg, heart rate was 108 beats/minute, respiratory rate 22/minute and oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. No murmur was detected. Peripheral signs of IE such as Janeway lesions, Splinter haemorrhage and Osler's nodules were absent. There were rales in both lung bases on lung auscultation. The remainder of his medical examination was unremarkable. Due to his personal medical history, a transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed without vegetation detected.

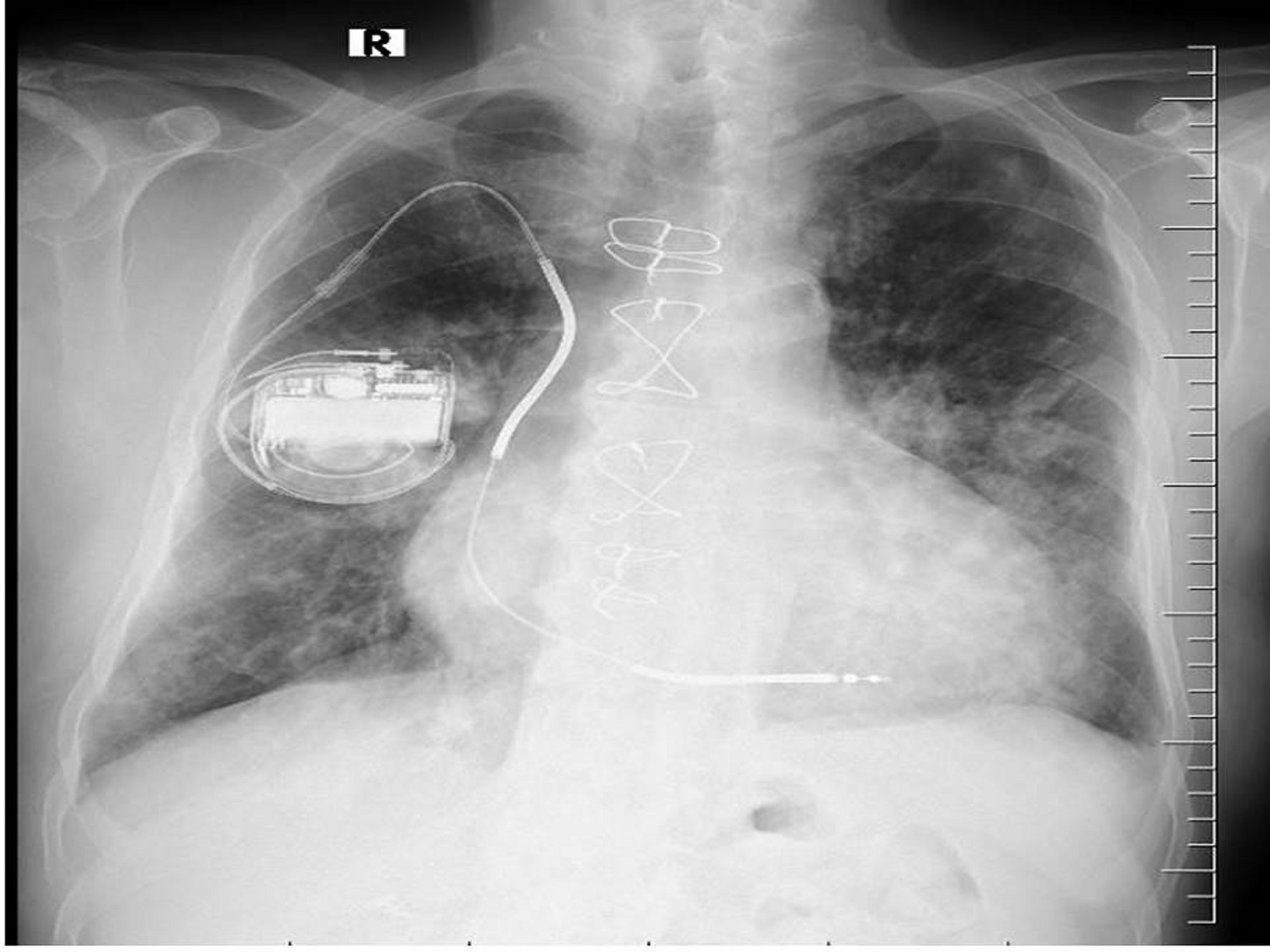

The patient was hospitalized for further examination with a prediagnosis of IE. Since the patient did not have a clear focus of infection (he had no signs of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, etc., and other viral-zoonotic infections), IE was considered as a preliminary diagnosis because he only had a CIED as a risk factor. Initial laboratory studies showed a white blood count of 18.9 x 109/L, a haemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dL and a platelet count of 192,100 /L. Urine analysis was showed 2+ blood, protein 1+. Biochemical blood analysis showed: normal electrolytes, liver and kidney function test and C reactive protein (CRP) at 10.4 mg/dl. There was no serological test results for HIV, HBV, HCV, CMV or EBV infection. A chest X-ray had bilateral basal infiltration and intracardiac device (ICD) (Figure 1). Ceftriaxone 1x2 g/day intravenous (i.v.) was begun empirically after six bottles of blood cultures were obtained. The blood culture samples incubated to BACTEC 9240 (Becton Dickinson Instrument System, Sparks, USA) and in six of them Corynebacterium spp. grew up. Phoenix100™ performed identification of the microorganism (Becton Dickinson Instrument System, Sparks, USA). The antibiotic susceptibility of the microorganism was determined be sensitive to vancomycin and linezolid, and resistance to cephalosporins, penicillin, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, meropenem, and clindamycin. Accordingly, ceftriaxone was stopped and vancomycin 1x2 g/day i.v. was started. The patient was consulted with cardiologist again with a prediagnosis of IE for trans-oesophageal echocardiography (TEE). The TEE revealed 0.9 mm dimensions mobile vegetation on the tricuspid valve anterior leaflet. After 72 hours of the treatment, surveillance blood cultures did not return negative. The CIED was removed and sent for culture and sensitivity. The same bacterial growth was obtained. After the removal of the CIED, the blood culture turned negative.

After a total of 6 weeks of vancomycin treatment, considering the significant improvement of the health conditions, the patient was discharged. One month after the discharge, a transesophageal echocardiogram was performed and showed no vegetation of the valve leaflets and he did not report any complications. At the three-month follow-up, he was in good health, afebrile, and had not relapse.

DISCUSSION

Permanent pacemaker (PPM), intracardiac defibrillator (ICD), and cardiac resynchronization therapy device (CRTD) are the most common CIEDs. The reported incidence of IE in patients with these devices is 0.5-5.7% and 1.8-10/1000 device year [9, 10]. Approximately 10% of all IE cases and in Turkey 7% of IE cases were reported to be associated with CIED [3]. The presented case had ICD associated IE. In 80% of IE cases, the causative agent is streptococci or staphylococci. Because of the increase in cases with health care associated infections in recent years, Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) are more common agents while the proportion of viridans streptococci decreased relatively [3]. The patient we presented had CIED and was diagnosed as IE due to Cornyebacterium spp., Cornyebactrium subtype classification could not be made.

Skin flora bacteria Corynebacterium spp. can cause IE, especially in the presence of artificial valves and other intracardiac devices. If they reproduce in all blood culture sets of patients who have been pre-diagnosed as having IE, it should be kept in mind that these microorganisms may also be causative, and the growth should not be considered contamination [3]. In the present case, Corynebacterium spp. grew in all (6/6) of the blood culture samples. He had no pocket infection findings.

The diagnosis of CIED-associated endocarditis is made by the presence of vegetation at the tip of the wire in a patient with signs and symptoms of systemic infection, with or without pocket infection or bacteremia/fungemia [3]. The presented case had blood culture positivity and vegetation at the tricuspid valve (diagnosed with TEE). He also had fever as symptom of systemic infection.

TTE and TEE may not be sufficient to exclude CIED-associated endocarditis. According to the guideline, 18F-FDG PET/CT or SPECT/CT marked leukocyte scintigraphy should be requested to exclude CIED-associated endocarditis [3]. The presented case's vegetation was detected in the TEE examination.

In previous studies Corynebacterium spp. have been associated with CIED-associated endocarditis [7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. In a study examining 30 IE episodes due to Corynebacterium spp., the median age of the patients was 71 years and 77% of them were male. C. striatum (n=11) and C. jeikeium (n=5) were the most common species [12]. In the literature, Corynebacterium spp. were defined into subtypes by using the VITEK 2 Compact (Biomerioux, France) automated system and the 16S rDNA sequence analysis methods [7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. Our patient was a 55-year old man and the subspecies analysis could not be performed because such examinations could not be performed in our center.

Multidrug-resistant C. striatum infections have occurred in patients who have been in the hospital for a long time and have been exposed to broad-spectrum antibiotics, as well as in patients who have intracardiac or endovascular devices, or who are immunocompromised [11]. Our patient was not immunocompromised and had an ICD. He also had no history of hospitalisation or antibiotic use. The antibiotic susceptibility of the microorganism was determined be sensitive to vancomycin and linezolid.

The duration of the treatment should be 2-4 weeks in wire endocarditis and 4-6 weeks in valve endocarditis with the removal of the device. In the treatment of septic patients with unstable hemodynamics, gentamicin, cefepime, or meropenem may be added to vancomycin treatment [3]. The presented case was treated with vancomycin for 6 weeks, and the device was removed.

CONCLUSIONS

The presented case is a rare Corynebacterium spp. cardiac device-related infective endocarditis case. Corynebacterium spp. are usually overlooked as contaminants in blood cultures, but they can also cause IE, which is a serious disease, especially in patients with cardiac devices. Corynebacterium spp. are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics, making treatment more difficult. In order to cure the patient, the infected devices needs also be removed. Furthermore, IE can be misdiagnosed using TTE, necessitating the use of further diagnostic procedures such as TEE. There are few reports of CIED caused by Corynebacterium spp., and more research is needed. This report demonstrated the importance of repeating blood cultures and TEE, for the diagnosis of CIED.