My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Archivos Españoles de Urología (Ed. impresa)

Print version ISSN 0004-0614

Arch. Esp. Urol. vol.62 n.1 Jan./Feb. 2009

Our experience in treatment of renal tumours with venous involvement

Tratamiento quirúrgico del tumor renal con extensión venosa

Joaquín Ulises Juan Escudero, Macarena Ramos de Campos, Pedro Navalón Verdejo, Sergio Cánovas López1, Milagros Fabuel Deltoro, Francisco Serrano de la Cruz Torrijos, Francisco Ramada Benlloch, Emilio Marques Vidal and Juan Martínez León1

Urology Service and Urolog y Cardiac Surgery Department1. Universitary General Hospital Valencia. Valencia. Spain.

SUMMARY

Objectives: Renal carcinoma accounts for 3% of malignant urological tumors. The existence of tumor thrombus in the venous system is more infrequent, and, despite it was believed until recently its presence worsened the diagnosis of the disease, currently it is accepted that in the absence of metastatic or lymph node disease, surgery is the treatment of choice and potentially curative for these tumors.

Methods: Between June 2003 and November 2007 eight patients with renal disease and venous thrombus underwent surgery; two of them wereT3c and six T3b; in five of them surgery was carried out in association with the heart surgery team in our centre. Three of them underwent surgery with extracorporeal circulation. Mean patient age was 56 years.

Results: Tumor thrombus was grade I in one patient, grade II in 4 patients, grade III in one patient, and grade IV in two patients. In all patients with tumor grade

> III, as well as two with grade II, surgery was performed in conjunction with the department of heart surgery. The operation with extracorporeal circulation, deep hypothermia, cardioplegia, and antegrade and retrograde brain perfusion was performed in grades III and IV. Midline incision was performed, with or without sternotomy, depending on the level of the thrombus. Hemorrhage was the most frequent perioperative complication.

Discussion: It is essential to know the exact level of the cephalic extreme of the tumor thrombus to design the proper surgical strategy; for that, we can use MRI, CT scan or ultrasound. Therefore, surgical approach, multidisciplinary cooperation and use of extracorporeal circulation will depend on such extension of the thrombus and concurrent factors of the patient. A good surgical strategy, as well as early surgery may avoid the use of venous filters preoperatively.

Conclusions: Venous wall invasion seems to be related with a greater incidence of lymph node disease, but these patients are candidates to intention-to-cure radical surgery. Thrombus level is not a prognostic factor per se, but it should be taken into consideration for surgical planning. After radical surgery survival rates achieved are similar to those of tumors without venous thrombus.

Key words: Renal tumour. Venous involvement. Surgical treatment.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: El carcinoma renal supone un 3% de los tumores malignos urológicos. Más infrecuente es la existencia de trombo tumoral dentro del sistema venoso y, si bien hasta hace poco se pensaba que su existencia ensombrecía el pronóstico de esta enfermedad, actualmente se acepta que en ausencia de enfermedad metastásica o ganglionar, la cirugía es el tratamiento de elección y potencialmente curativo para estos tumores.

Métodos: Entre Junio de 2003 y Noviembre de 2007 hemos intervenido un total de 8 pacientes con enfermedad renal y trombo venoso, de los cuales 2 eran T3c y seis T3b, cinco de ellos fueron intervenidos junto con el servicio de cirugía cardiaca de nuestro centro. Tres de ellos fueron intervenidos con circulación extracorpórea (CEC). La media de edad de los pacientes fue de 56 años.

Resultados: El trombo tumoral era grado I en un paciente, grado II en 4 pacientes, grado III en 1 paciente y grado IV en dos pacientes. Todos los pacientes con grado tumoral igual o mayor de III, así como dos grado II, fueron intervenidos conjuntamente con el servicio de cirugía cardiaca, realizando en los grado III y IV la intervención con circulación extracorpórea, hipotermia profunda con parada cardiorrespiratoria y perfusión cerebral anterógrada y retrógrada. Se realizó incisión media con o sin estereotomía media dependiendo del nivel del trombo. La complicación más frecuente acaecida peroperatoriamente fue la hemorragia.

Discusión: Es esencial conocer el nivel exacto de la extensión cefálica del trombo tumoral para diseñar una adecuada estrategia quirúrgica, para lo que nos podemos valer de la resonancia magnética (RM), de la tomografía computerizada (TC) y de la ecocardiografía. Así el abordaje quirúrgico, la colaboración multidisciplinar y el empleo de CEC dependerá de dicha extensión y de los factores concomitantes presentes en el enfermo. Una buena estrategia quirúrgica, así como una cirugía temprana pueden evitar el uso de filtros venosos de forma preoperatoria.

Conclusiones: La invasión de la pared venosa parece estar relacionada con una mayor incidencia de enfermedad ganglionar, pero estos pacientes son candidatos a la cirugía radical con intención curativa. El nivel del trombo, si bien puede dificultar la cirugía, no es un factor pronóstico per se, y si debe ser tenido en cuenta para la planificación quirúrgica. Tras la cirugía radical se alcanzan cifras de supervivencia superponibles a los tumores sin trombo venoso tumoral.

Palabras clave: Tumor renal. Extensión venosa. Tratamiento quirúrgico.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma has the highest mortality rate of all urological malignant tumours and consists on the 3% of all of them (1). In the last years, due to the high incidental detection rate during the study of any other pathology. We have assisted to an increase of its incidence of about the 2.5% each year although its mortality has not reached a decrease as it would be foreseeable. This is due to a change in its aggressiveness because of pathogenic and environmental factors that have led to a negative modification of its biology. It is more frequent among men, on the sixth and the seventh decade of life.

The main pathogenic factor is smoking. Obesity and hypertension treatment have been demonstrated to be risk factors too independent on smoking. Leaving smoking has been demonstrated as the strongest way to primarily prevent renal cancer (2).

As we commented previously, thanks to the extended use of ultrasound and computed tomography the number of incidental tumours has raised to 50% of all cases. The classical triad of hematuria, pain and flank mass only is presented in about 10% of patients. To achieve a good diagnosis, MR and CT are mandatory, abd result very useful to plan a surgical treatment.

Nowadays it is accepted the 1997 modified TNM classification where changes in T1,T2 and T3 stages were introduced, separating venous extension between up and below the diaphragm, as well as introducing nodal involvement since it was not observed in Robson's classification. Pathological findings, nodal involvement and presence of metastases have been proved as the main prognostic factors in these patients (3,4).

Venous involvement was supposed to worse their prognostic, but currently we know that patients who undergo salvage nefrectomy have a survival ratio at five years from abuot the 45 and 70%, may be the cephalic extension of the thrombus present more controversies, but in this way, involvement of the venous wall has a fateful prognostic.

In this work we report our experience in diagnosis and treatment of renal cell carcinoma with venous involvement, analyzing surgical techniques and results from these technique.

Material and methods

Between July 2003 and November 2007 we made an amount of 8 radical nefrectomies in our hospital with vena cava thrombus excision in the treatment of T3b and T3c patients. Mean age was 56 years (range 25-80) half of them were male. We used ECC with circulatory arrest, deep hypothermia anterograde and retrograde perfusion to assist thrombectomy in 3 patients. Preoperatively, all patients underwent detailed anamnesis, physical exam, computed tomography of the pelvis, abdomen and thorax and vascular and urographic CT, four patients underwent MR and all of them completed an ultrasonografic heart study. We collect and analyze intraoperative and postoperative complications. Patients underwent CT controls for their surveillance at 3,6,9 and 12 months, every 6 months from then on and one each year later on.

Results

Five of the patients presented hematuria at the time or before the time of diagnosis, three of them refered flank pain too. Of the other three, one was an incidental diagnosis after the labor and absolutely incidental in other two. All of them presented a good Karnofsky preoperatively (all above 80). Five patients were smokers at the time of diagnosis or have left the habit on the last five years, two of them took antihypertensive treatment. A Renal mass was palpable in two patients.

In order to use an standard for classification of venous involvement we used CT with vascular and urographic study, accomplishing the diagnosis with ecocardiography that confirmed the auricular involvement in two of our patients. MR was done in our four first cases.

Five cases were right and three were left kidneys. The length of the tumours ranged from 4 to 17cm (media 8,5). Tumour thrombus following Montie et al classification were degree I in one patient, degree II in 4 patients, degree III in one patient and degree IV in two patients.

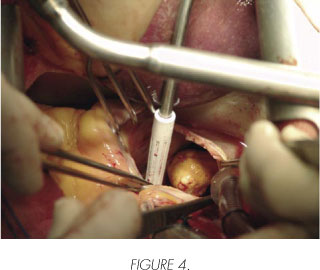

All patients with degree III or more and two in degree II underwent surgery with the help of cardiovascular surgeons, undergoing ECC in degree III and IV, in these cases we made a thoraco-abdominal incision with medium esthernotomy, mobilizing liver and colon to achieve a better control of the affected kidney pedicle.

To the three patients operated in our service we made a subxifoid incision, upper or infraumbilical if necessary in order to mobilise later colon to expose the vena cava and aorta at both sides and a wide upper caval dissection avoiding to damage it in order to create a good scenary previously to clamp it. We removed the ostium of the affected kidney in all cases.

In both techniques, the first step is the dissection of the affected pedicle dissect later the vena cava and aorta. Then we control the pedicle separately with a vessel loop and so do we with the aorta and the cava. The first step is to remove the kidney in order to proceed later to the excision of the venous thrombus opening the cava vein infradiaphragmatic or infra and supra diaphragmatic with auricular acces too in degrees II and IV. The last step we made was to remove the ostium of the renal vein.

The case on degree III underwent extraction of a filter on cava vein, so we made a safe access to it opening right atrium and avoiding embolism. One of the cases on degree IV presented an embolism of a lung artery, so it was necessary to open right pulmonary artery to extract it.

Mean operative time was 210 minutes (range 150-300). Mean blood loss was 470cc (range 200-2000cc). We used a system to recovery blood from the operative field. A media of 2,3 transfussions were indicated intra and postoperatively (range 0-6). We didn't notice any other mayor complication during surgery, all patients were discharged the eight day postoperative. None of our patients presented neurological alterations postoperatively.

In two of the eight tumours resected, we found venous wall invasion that did not achieve to the ostium. In four cases tumoral thrombus component was identified with extension far away the renal vein, being in all the rest of cases hematic the component of the thrombus.

Just 1 patients had Furhmen degree 1, 3 degree 2 and 4 degree 3. Resection limits were negative for tumour in all cases.

Currently the follow-up range is from 1 to 48 months, two of the patients have died, media of disease free survival was 38 months, one of our patients presented recurrent disease on the month 38 of follow up and another one on the seventh month.

Discussion

Until the decade of 90, the most commonly system used to clasiify renal tumours was the modification of Flocks and Kadesky made by Robson (2). This system presents a problem for tumours on stage III, and includes in the same stage neoplasms with nodal and vascular involvement, and as now we know the first ones present worst prognostic and the second ones are due to be treated with salvage surgery successfully. Separation between both kinds of affectation reports similar survival rates for stages II and III.

TNM introduced an advance in classification as it distinguishes between nodal and venous involvement, so it is 1997 TNM classification the one we use nowadays. This classification separates the tumours according to the thrombus level on T3b renal vein and cava vein subdiaphragmatic involvement and T3c supradiaphramatic involvement. We have used Montie et al classification because we consider it is more useful at the time of planning surgery, and it is helpful to make the level of the thrombus more comprehensive.

The presence of non reducible varicocele, low extremity edema, dilatation of abdominal superficial veins, or mass on right atriumin the context of renal kidney tupours is indicative of venous involvement. In our patients, the most common sign was hematuria, being the renal mass less common.

Sensitivity rates for CT to detect venous involvement rages for 78% on renal vein to 98% on cava vein. Indirect signs of venous involvement are, icrease on venous diameter, decrease of density and filling defects and collateral circulation (1,2). MR is a safe diagnostic technique, avoids renal toxicity of iodated contrasts and is considered by many autors (6,7) to be the elective one to explore the venous invasion in inferior cava vein, and it is able to distinguish between haematic and tumoral thrombus. So we consider it elective on allergic patients to iodate contrast media and those with renal impairment, echo gradient secuences represent the most effective way to determine the thrombus extension and detection allowing reconstruct venograms. Paramagnetic contrast is a useful weapon to difference simple thrombus of tumoral ones (8).

In our experience, CT offers a better image quality, higher sensitivity to detect venous thrombus and the capability to obtain vascular and urographic images in only one time if necessary, and this is quite useful to plan surgery. It is a cheaper and more accessible exploration. In all our patients, the thrombus level described on CT did not differed from the one seen intraoperatively, but in two of our four firs cases the level described on MR did. Just because of this we stopped performing MR routinely in our patients. The mayor problem for radiological exams is to determinate accurately the invasion of the venous wall of the thumour, and this is an ominous prognostic factor for this patients and most of the times we have to wait to pathological findings to ensure there is no wall invasion. Venocavography has been used to complete the study of these patients when MR or CT are not enough to achieve an accurate diagnostic, but nowadays its use is out of order. Transesophagic echography is an invasive procedure with a high efficacy and in many times do not improve CT or MR accuracy. Coronary angiography may be necessary in order to plan ECC depending on the cardiovascular risk and patient's comorbidity.

Venous involvement in renal cell carcinomas has usually been considered as a poor prognostic factor, but in recently it has been demonstrated that 5 years survival rate in these patients with no metastatic disease rises to 70% (2,9). Prognostic value of upper extension of the thrombus is still under disclosure, but in our experience, to divide it on upper or lower diaphragmatic extension, distinguishing the atrium involvement and the relation with the liver has helped us to decide the optimal surgical technique and the approach to the tumour. We think that Montie et al classification is the most adequate to plan surgical treatment, but it has a problem to distinguish between upper or lower thrombus respect to the liver and atrial involvement, and in our opinion it has a great importance in order to plan liver mobilisation and to perform ECC.

We do not agree with other authors (10,11) of the convenience to put a cava filter preoperatively, we prefer to start antithromboembolic therapy early and avoid to delay surgery as much as possible. An optimal and fast preoperative planning avoids using filter in most cases.

The aim of every oncological surgery must be the complete resection of the tumour and thrombus, but this surgery often requires a multidisciplinary approach including urological, cardiovascular surgeons as well as anaesthesiologist and oncologists. The first item to determinate whether to chose one access to the tumour will depend on the level of the thrombus, traditionally for a thrombus above the diaphragm an toracoabdominal laparotomy was needed, but nowadays some advantages have been described with a Chevron incision extended on inverted T with or without Langebuch manoeuvre in order to mobilise the liver, we still think that the firs incision offers a good exposition of the retroperitoneal structures and allows an easier access to retrohepathic cava vein (12). In case of only infradiaphragmatic thrombusmultiple accesses have been described as hemichevron, chevron plus xifoid extension or subcostal incision (9,13,14). So, based on the anterior comments we use laparotomy as the incision of choice and it allows us to extend the incision upper to de sternum. Also we try not to move, as much as possible, the cava vein in order to not spread the thrombus at least before to clamp the cava (15).

The use of ECC seems to be unnecessary for level I and II tumours, it its controversial its use on level II tumours, but we used it because of the risk to extract the filter, in order to extract it on safely we designed a double access to cava vein plus an incision on atrium. It is less controversial to use ECC in thrombus above de diaphragm, mainly whe it gets to right atrium. ECC allows to make an extended dissection avoiding massive bleeding and to achieve a better surgical field because of the better surgical field (5,16). On the other hand, as disadvantages we find the higher risk of solid organs ischemia, coagulopathy and neurological events. Some author prefers not to do it if the thrombus level does not get to the atrium or to do moderate hypothermia on suprahepathic thrombus (15).

Less frequent is the invasion of the venous wall either renal or cava vein. In these cases and those chronically obstructed, it is indicated to resect affected vascular wall (17) with or without interposition of synthetic polyethylene patch. In our series we systematically extract the ostium of the renal vein indepently of the suspicion on its affection we think it does not rise surgical risk and may determinant on prognostic.

It is more controversial to make lymphatic node dissection, because, although it does not offer any advantage on metastasic disease, nor increases morbidity, its usefulness is not yet demonstrated in cases with located or locally advanced tumour in therms of oncological results (17).

Intraoperative mortality varies between 6 and 10% depending on series (10,18). The first cause of death in these patients is massive lung thromboembolism and strokes. In our series, we did not find remarkable morbidity, although it is too short to extract consistent conclusions.

Metastasic or nodal disease results in a decrease of free disease survival, but venous and fatty tissue involvement implication on survival seems to be more controversial (19). Ficarra et al (3) describe a risk stratification on three groups low risk, with those on lower diaphragmatical level of thrombus or fatty tissue infiltration, an intermediate risk group with lower diaphragmatic and fatty tissue infiltration or suprarenal involvement and a high risk group including suprdiaphragmatic thrombus, gerota's involvement and infradiaphragmatic and suprarenal affectation. Survival is of 67 to 117, 24 and 12 months respectively (2). Survival rates at five years in patients with no metastatic disease and venous involvement veries from 30 to 72% (18) in patients undergoing salvage surgical therapy.

Conclusions

Venous wall infiltration increases the risk of nodal affection but venous thrombus is not so related with nodal involvement or metastasic disease, because of this, these patients are candidates to salvage surgical therapy.

In our experience, the level of thrombus has changed the surgical approach, but it has nor been a prognostic factor itself, so it has to be taken in account to plan surgery. We think as other authors, that employing ECC is a very useful technique when Thrombus level is over suprahepatic veins, and it does not increase morbidity and allows an easier access to cava vein, so we think it is recommendable when a prepared surgical team is familiar with this technique, so a multidisciplinary approach is mandatory on these tumours.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Joaquin Ulises Juan Escudero

Avenida Juan Carlos I, 7

03370 Redován. Alicante. (Spain).

chimojuan@hotmail.com

Accepted: 30th January, 2008.

References and recomended readings (*of special interest, **of outstanding interest)

1. Rodríguez A and Sexton WJ: Management of locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer control 2006; 13: 199. [ Links ]

2. Lungberg B, Hanbury DC, Kuczyk, MA, Merseburger, and AS: European Urology Association Guidelines on renal cell carcinoma. European Urology 2007; 4. [ Links ]

3. Ficarra V, Galfano A, Guille F, Schips L, Tostain J, Mejean A et al.: A new staging system for locally advanced (pT3-4) renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter European study including 2,000 patients. J Urol 2007; 178: 418. [ Links ]

4. Haferkamp A, Bastian P J, Jakobi H, Pritsch M, Pfitzenmaier J, Albers P et al.: Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus extension into the vena cava: prospective long-term follow-up. J Urol 2007; 177: 1703. [ Links ]

5. Montie JE, el Ammar R, and Pontes JE: Renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombi. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1991; 173: 107. [ Links ]

6. Boorjian S A and Sengupta: Renal cell carcinoma: vena caval involvement. BJU International 2007; 1239. [ Links ]

7. Blute M L, Boorjian S A, Leibovich B C, Lohse C M, Frank I, and Karnes R J: Results of inferior vena caval interruption by greenfield filter, ligation or resection during radical nephrectomy and tumor thrombectomy. J Urol 2007; 178: 440. [ Links ]

8. Cuevas C, Raske M, Bush W H, Takayama T, Maki J H, Kolokythas O et al.: Imaging primary and secondary tumor thrombus of the inferior vena cava: multi-detector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2006; 35: 90. [ Links ]

9. Kirkali Z and Van P H: A critical analysis of surgery for kidney cancer with vena cava invasion. Eur Urol 2007; 52: 658. [ Links ]

10. García O D, Fernandez F E, de V E, Honrubia A, Moya J L, Abella V. et al.: [Surgical stratification of renal carcinoma with extension into inferior vena cava]. Actas Urol Esp 2005; 29: 448. [ Links ]

11. Wellons E, Rosenthal D, Schoborg T, Shuler F, and Levitt A: Renal cell carcinoma invading the inferior vena cava: use of a "temporary" vena cava filter to prevent tumor emboli during nephrectomy. Urology 2004; 63: 380. [ Links ]

12. Wotkowicz C, Libertino J A, Sorcini A, and Mourtzinos A: Management of renal cell carcinoma with vena cava and atrial thrombus: minimal access vs median sternotomy with circulatory arrest. BJU Int 2006; 98: 289. [ Links ]

13. Jibiki M, Iwai T, Inoue Y, Sugano N, Kihara K, Hyochi N et al.: Surgical strategy for treating renal cell carcinoma with thrombus extending into the inferior vena cava. J Vasc Surg 2004; 39: 829. [ Links ]

14. Modine T, Haulon S, Zini L, Fayad G, Strieux-Garnier L, Azzaoui R et al.: Surgical treatment of renal cell carcinoma with right atrial thrombus: Early experience and description of a simplified technique. Int J Surg 2007. [ Links ]

15. Ruibal M, Álvarez L, Chantada V, Blanco A, Fernández E, and González M: Cirugía del carcinoma renal con trombo tumoral en vena cava. aurícula. Actas Urol Esp 2003; 27: 517. [ Links ]

16. Marshall FF, Reitz BA, and Diamond DA: A new technique for management of renal cell carcinoma involving the right atrium: hipotermia and cardiac arrest. J Urol, 1984; 131: 103. [ Links ]

17. Ciancio G and Soloway M: Resection of the abdominal inferior vena cava for complicated renal cell carcinoma with tumour thrombus. BJU Int 2005; 96: 815. [ Links ]

18. Tsui Y, Goto A, Hara I, and Ataka K: Vena caval involvement by renal cell carcinoma. Surgical resection provides meaningful long-term survival. Journal of vascular surgery 2001; 33: 789. [ Links ]

19. Shinsaka H, Fujimoto N, and Matsumoto T: A rare case of right varicocele testis caused by a renal cell carcinoma thrombus in the spermatic vein. Int J Urol 2006; 13: 844. [ Links ]

text in

text in