Dear Editor,

BK polyomavirus (BKV) causes latent, asymptomatic infection in immunocompetent individuals. In the setting of immunosuppression BKV can reactivate and lead to BK virus nephropathy (BKVN) in renal transplant recipients.1 BKVN is one of the main causes of allograft failure in renal transplant patients. Acute rejection and different viral infections should be considered in differential diagnosis of renal allograft dysfunction. Electron microscopy (EM) could help to distinguish BKV from other viral factors in allograft tissue.2 Herein, we described inclusions due to BKV seen by EM in a renal transplant biopsy and we discussed potential role of EM in diagnosis of BKVN.

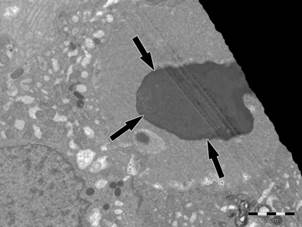

A 49 years old woman had renal transplantation from non-relative donor 2 years ago. Although she was asymptomatic, her serum creatinine level was increased gradually during last 3-4 months (from 1.2 mg/dl to 1.7 mg/dl). Her primary renal disease was unknown. She had been under the treatment of tacrolimus 2 + 1 mg, prednisolone 5 mg, mycophenolate sodium 3 × 360 mg. Physical examination was normal. Serum creatinine was 1.82 mg/dl, urine microscopy was normal. 154 mg/day proteinuria was obtained. ANA was positive, though ENA was negative. Anti CMV IgM was negative, whereas serum BK/JC PCR was positive. Serum tacrolimus level was 9.5 ng/ml. Transplant renal doppler ultrasonography revealed normal findings. Renal biopsy was performed. Intranuclear inclusions, cytoplasmic and nuclear enlargement in tubular epithelial cells and tubular necrosis were seen on light microscopy. These biopsy findings might suggest viral infection of the renal allograft. Immunohistochemical analysis of the renal biopsy for CMV was negative, but study with SV40 antigen could not be performed as it was not available in our center. Intranuclear spherical viral particles were seen in some tubular epithelial cells on EM (Fig. 1). Viral particles were in paracrystalline structure and about 30 nm in diameter. They were differentiated from inclusions of adenovirus with 80-100 nm in diameter (Fig. 2). Finally, BKVN was diagnosed.

Fig. 2 Intranuclear inclusions in higher magnification. Spherical viral particles with a diameter of 30 nm (60,000×).

BKVN is one of the well-known reasons of morbidity in renal transplant patients. It occurs with a prevalence of 1-10% in renal transplant patients and graft loss is up to 80%.3,4 BKVN occurs mostly during the first year after transplantation and it is characterized only by deterioration of renal functions, usually without any symptoms.1 Early diagnosis is important to prevent allograft dysfunction in kidney transplant patients. Our patient was also declared no symptoms, but only a gradual increase in serum creatinine was observed in the second year of follow up.

The pathogenesis of BKVN is characterized by high grade BKV replication in renal-tubular epithelial cells of renal allograft. Necrosis of tubular cells let BKV leak into the tissue and blood, and then inflammatory cell infiltration to interstitium occurs. This leads to tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and therefore impaired graft function. Intensive immunosuppressive therapy is the leading risk factor in the development of BKVN.4

Plasma and urine polymerase chain reaction (PCR), urine cytology, and urine electron microscopy (EM) can be performed in diagnosis of BKVN whereas renal biopsy is the gold standard method.3,5 Multiple biopsy should be performed because of multi-focal involvement to prevent sampling errors and biopsy specimen should contain medullary parenchyma as the virus is more likely to present in the medulla.5 Intranuclear inclusions, lysis or necrosis of tubular cells showing tubulointerstitial inflammation could be observed on light microscopy. However, changes observed during light microscopy are not pathognomonic for BKVN. Immunohistochemistry (SV40 staining) and EM should be performed.6

Herpes simplex virus, adenovirus, CMV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) should also be considered in differential diagnosis as they may cause similar histologic findings. Immunohistochemistry and EM can be helpful in differential diagnosis.6-8 Viral particles of BKV are characteristically 30-50 nm in diameter and occasionally form crystalloid structures, whereas inclusions due to family of herpesviridae (including Herpes simplex, EBV and CMV) and adenoviruses are bigger in size (120-150 nm and 70-90 nm respectively).2,6,9,10

In our patient, size of the viral particles was 30 nm in average. Although light microscopic detection of intranuclear inclusions suggested viral infection of renal allograft, it was the EM that defined dimensions of inclusions and helped the diagnosis. In conclusion, EM evaluation of allograft biopsy may be important in the differential diagnosis of different viral infections of allograft.