Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Nutrición Hospitalaria

versión On-line ISSN 1699-5198versión impresa ISSN 0212-1611

Nutr. Hosp. vol.34 no.5 Madrid sep./oct. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.20960/nh.1037

Eating disorders during the adolescence: personality characteristics associated with anorexia and bulimia nervosa

Trastornos de la conducta alimentaria durante la adolescencia: perfiles de personalidad asociados a la anorexia y a la bulimia nerviosa

Belén Barajas-Iglesias1,2, Ignacio Jáuregui-Lobera3, Isabel Laporta-Herrero2 and Miguel Ángel Santed-Germán2

1Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa. Zaragoza, Spain.

2Facultad de Psicología. Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED). Madrid, Spain.

3Section of Nutrition and Bromatology. Universidad Pablo de Olavide. Seville, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Previous studies provide relevant information about the relationship between personality and eating disorders (ED). The involvement of personality factors in the etiology and maintenance of ED indicates the need of emphasizing the study of the adolescent's personality when diagnosed of ED.

Objectives: The aims of this study were to analyze the adolescent's personality profiles that differ significantly in anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN), and to explore the most common profiles and their associations with those subtypes of eating disorders (ED).

Methods: A total of 104 patients with AN and BN were studied by means of the Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory (MACI).

Results: The personality profiles that differ significantly in both AN and BN were submissive, egotistic, unruly, forceful, conforming, oppositional, self-demeaning and borderline. The most frequent profiles in AN were conforming (33.33%), egotistic (22.72%) and dramatizing (18.18%) while in the case of BN those profiles were unruly (18.42%), submissive (18.42%) and borderline (15.78%). We did not find any associations between the diagnostic subgroup (AN, BN) and the fact of having personality profiles that could become dysfunctional.

Conclusions: Bearing in mind these results, it may be concluded that there are relevant differences between personality profiles associated with AN and BN during adolescence, so tailoring therapeutic interventions for this specific population would be important.

Key words: Personality. Anorexia nervosa. Bulimia nervosa. Adolescence.

RESUMEN

Introducción: estudios previos aportan información relevante sobre la relación entre la personalidad y los trastornos de conducta alimentaria (TCA). La implicación de los factores de personalidad en la etiología y el mantenimiento de los TCA indica la necesidad de enfatizar el estudio de la personalidad del adolescente cuando se diagnostique un TCA.

Objetivos: los objetivos del presente estudio fueron explorar los perfiles de personalidad más frecuentes asociados a la anorexia nerviosa (AN) y a la bulimia nerviosa (BN) en adolescentes y analizar aquellos perfiles de personalidad que diferencian de manera significativa a ambos subtipos de TCA.

Métodos: un total de 104 pacientes con diagnóstico de AN y BN fueron estudiados mediante el Inventario Clínico para Adolescentes de Millon (MACI).

Resultados: los perfiles de personalidad que difieren significativamente entre AN y BN fueron los perfiles sumiso, egocéntrico, rebelde, rudo, conformista, oposicionista, autopunitivo y tendencia límite. Los perfiles de personalidad más frecuentes en la AN fueron el conformista (33,33%), el egocéntrico (22,72%) y el histriónico (18,18%), mientras que en la BN los más prevalentes fueron el rebelde (18,42%), el sumiso (18,42%) y el límite (15,78%). No encontramos ninguna asociación entre el subgrupo diagnóstico (AN, BN) y el hecho de tener perfiles de personalidad que podrían llegar a ser disfuncionales.

Conclusiones: existen diferencias relevantes entre los perfiles de personalidad asociados a la AN y la BN durante la adolescencia, por lo que sería importante adaptar las intervenciones terapéuticas para esta población específica.

Palabras clave: Personalidad. Anorexia nerviosa. Bulimia nerviosa. Adolescencia.

Introduction

The relationship between personality characteristics and eating disorders (ED) has been analyzed in many studies (1-3). Studies on ED have been developed from two different points of view. Following a categorical perspective, studies have focused on the comorbidity between personality disorders (PD) and ED. On the other hand, from a dimensional view (based on the continuum of personality traits), studies have analyzed the relationships of different personality characteristics with ED. Considering the first perspective, some authors have studied the presence of borderline personality disorder (BPD) in patients with bulimia nervosa (BN), anorexia nervosa (AN), women at risk of developing an ED and women without any psychopathology. These authors have concluded that patients with BN were those with the highest rate of borderline personality traits as well as PD (4). In another study, various authors compared a sample of patients with AN-restrictive type (AN-RT) vs patients with BN by means of the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI-II) (5). They found a higher frequency of PD of cluster A and C (schizoid and avoidant) in AN-RT and PD of cluster B (histrionic) in case of BN (6). In addition, higher frequency of obsessive PD in AN (39.77%) and the highest prevalence of histrionic PD in BN patients (46.66%) have also been confirmed (2).

Previous categorical studies provide relevant information about the relationship between personality and ED. Nevertheless, those studies have certain limitations. The methodological variability inter-studies is based on differences related to the participants' sex and age, the use of patients with different ED severity and course and differences with respect to the diagnostic criteria used, among others. Based on these reasons, it is important to understand personality pathology in a dimensional way thus clarifying differences among ED groups (7).

When personality is studied as a dimension, it has been shown that women with AN have a personality style defined by rigidity, over-control, obsessionality and perfectionism (8,9). Studies focused on women with BN have highlighted some characteristics such as impulsivity, disorganization and affective lability (10,11). Following the dimensional perspective, recent studies have been focused on the temperament and its neurobiological correlates in ED. In this regard, AN patients are characterized by rigidity, anxiety, reward insensitivity and altered interoceptive awareness (12-15).

Adolescence is a period with relevant biological, psychological and sociocultural changes. These changes require a high level of flexibility in order to get the adult period of life successfully. In this regard, adolescence is a period of vulnerability with respect to the development of ED (16). The involvement of personality factors in the etiology and maintenance of ED (17) indicates the need of emphasizing the study of the adolescents' personality when diagnosed with ED. Personality patterns have been shown to be useful to predict symptomatology and prognosis as well as the results of treatment (18). Longitudinal studies show that the initial evaluation of personality characteristics is useful to identify patients with bad prognosis and, at the same time, it is a proper tool in order to select the most effective therapeutical approaches (19).

Bearing in mind the above mentioned comments, it seems necessary to remark the study of personality (from a dimensional point of view) in adolescents with disordered eating from different theoretical frameworks, thus improving the treatment results of these patients. In the current study, following the Millon's model, we aim to add some research data in the field of personality in adolescents with ED. On the one hand, the Millon's model is useful to explore personality as a dimension. As a result, it is possible to obtain personality profiles as a continuum thus giving better information. On the other hand, the Millon's model permits the development of categorical analyses, which leads to possible comparisons between our results and those reported in previous studies about the comorbidity between ED and PD in adults. This is possible due to the similarity between the Millon's personality dimensions and the PD as listed in DSM-IV-TR (20). There is a shortage of research on personality of ED adolescent patients following the Millon's model. There is a controlled study with adolescent females suffering from ED by means of the Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory (MACI). This study concluded that the ED group showed significantly higher scores on self-demeaning, borderline and inhibited profiles, when compared with the control group (21).

The current study shows personality profiles following the Millon's model. Millon stated (22,23) that personality could be defined as a complex pattern of psychological characteristics which are deeply rooted and mainly unconscious. These intrinsic and general traits are the result of a complicated matrix of biological determinants and learning, thus yielding an idiosyncratic way of perceiving, feeling, thinking, behaving and relating to others. Despite some types of personality are prone to develop more pathological varieties in the future, it must be noted that in the current study it is not possible to refer to PD but to personality profiles. This is due to the fact that at the participants' age it is not possible to refer to stable and long-term patterns of personality as the DSM-IV-TR (20) establishes for PD. The objectives of this study were: a) to analyze differences in the personality profiles of AN and BN patients (considering the average scores in each profile); b) to analyze the frequency of patients presenting each personality profile in the group of AN and BN; and c) to assess the possible associations between diagnostic subgroups and the presence of specific personality profiles. Summarizing, this study aims to provide a better understanding of the personality types associated to AN and BN in adolescents and to contribute to the development of adequate treatment protocols specifically focused on each type of ED.

Methods

PARTICIPANTS

The sample comprised 104 participants aged between 13 and 18 years (15.47 ± 1.43). There were seven men (6.7%) and 97 women (93.3%). The sample was selected from the population of patients requiring treatment in the University Hospital-Eating Disorders Unit (EDU) of Zaragoza (Spain).Data were collected between January 2008 and June 2012. The method used for this study was non-probabilistic intentional sampling, selecting those participants who met the following inclusion criteria: a) AN (n = 66) or BN (n = 38) diagnosis; and b) having obtained valid scores in MACI (a MACI protocol must be invalidated when the validity and transparency scales are not properly performed). The existence of a neurological disease and mental retardation were the excluded. ED not otherwise specified (EDNOS) were also excluded due to the presence of mixed symptomatology of both AN and BN, and bearing in mind that the aim of this study was to explore characteristics of personality specifically associated to AN and BN. All participants in this study were outpatients and they were under their first treatment. The demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in table I. The AN group consisted of 66 patients and the group of BN comprised 38 patients.

INSTRUMENTS

The diagnosis of ED was performed by means of clinical interviews following the DSM-IV-TR criteria (20) and was carried out by the EDU psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. In order to complete the clinical assessment, a series of questionnaires was administered. Thus the Eating Attitudes Test-40 (EAT-40) (24,25) and the Bulimic Investigatory Test, Edinburgh (BITE) (26,27), were used.

The personality profiles associated with the ED subtypes were analyzed with the MACI (5). This inventory is a self-administered instrument, which consists of 160 items (answered true/false), designed for ages between 13 and 19 years and individually performed. It has been adapted for a Spanish population providing differentiated scales by age and sex as well as adequate levels of reliability and validity (construct, internal and external validity) (28).

The MACI evaluates seven clinical syndromes, twelve personality profiles and eight scales of evolutionarily normal concerns, which by excess or defect could influence the comorbidity. Following the objectives of this study, we focus on the 12 personality profiles, which are: 1) introversive; 2A) inhibited; 2B) doleful; 3) submissive; 4) dramatizing; 5) egotistic; 6A) unruly; 6B) forceful; 7) conforming; 8A) oppositional; 8B) self-demeaning; and 9) borderline. Additionally, it has a reliability scale (W) and three modifier scales: (X) disclosure, (Y) desirability and (Z) debasement.

All raw scores of MACI become base rate scores (BRS) by means of normative groups and based on the objective prevalence rates. The BRS are expressed on a linear scale of 115 points, thus yielding four possible ranges: (0-60) unlikely presence of the profile, concern or syndrome; (61-74) slightly probable; (75-84) moderately probable; and (≥ 85) highly probable.

PROCEDURE

This is an ex post facto design conducted in the above-mentioned EDU. The patients' process of evaluation included individual interviews and it was completed with the subsequent application of the questionnaires, including the MACI. This inventory was administered in all cases at the beginning of the treatment in the EDU. When patients are referred to EDU (generally from pediatrics) after detecting eating symptoms or weight loss, clinical interviews and application of questionnaires are the first step of the therapeutical process. At the beginning of treatment, patients' nutritional status varies depending on different factors (pathology, when patients have been referred, etc.). Both diagnosis and personality evaluation are the first part of treatment in the EDU. Professionals of EDU established the corresponding diagnosis and some patients' demographic data were collected among those who met the inclusion criteria and who attended the EDU between January 2008 and June 2012. Access to the patients' medical records was conducted exclusively for research purposes and written informed consent was obtained from participants and their parents. During the data collection process, any identifiable material was discarded and the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants who became part of the database were assured.

Results

By means of a dimensional (continuum) perspective of personality, the differences between AN and BN patients with respect to the personality profiles were analyzed comparing the BRS mean scores in each personality profile. Table II shows the results obtained by means of an ANOVA including all MACI personality profiles. Significant intergroup differences were found for the following profiles: submissive, egotistic, unruly, forceful, conforming, oppositional, self-demeaning and borderline. Patients with AN showed a profile with BRS mean scores more submissive (F [1] = 3.26; p < 0.05), egotistic (F [1] = 4.26; p < 0.05) and conforming (F [1] = 22.85; p < 0.05) than the BN group. In contrast, BN patients obtained higher mean scores on the following profiles: unruly (F [1] = 6.35; p < 0.05), forceful (F [1] = 6.44, p < 0.05), oppositional (F [1] = 8.41; p < 0.05), self-demeaning (F [1] = 8.64; p < 0.05) and borderline (F [1] = 8.64; p < 0.05). Finally, no significant differences in the introversive, inhibited, doleful and dramatizing profiles were found.

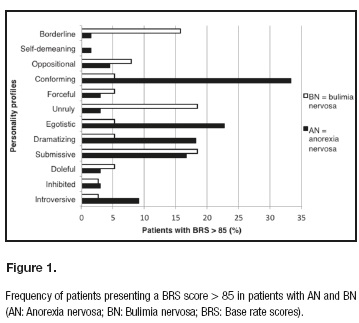

When a categorical perspective is used (specific personality profiles based on a cut-off point of 85 for the BRS), the frequency of the personality profiles associated to the AN and BN groups are those shown in figure 1. In order to determine the presence of a personality profile, a new dichotomous variable was created: "presence/not presence of each personality profile". A criterion of BRS > 85 was applied in each personality profile. Afterwards, the possible significant association between "to have/not to have a specific personality profile" and "to suffer from AN or BN" was analyzed by means of contingency tables and performing the X² test. Significant associations between the conforming (X² [1] = 7.775, p < 0.05), egotistic (X² [1] = 5.739, p < 0.05), unruly (X² [1] = 7.226, p < 0.05) and borderline (X² [1] = 7.827, p < 0.05) profiles and having AN or BN were found. The most common profiles in the AN group were conforming (33.33%) and egotistic (22.72%), while in patients with BN the unruly (18.42%) and borderline (15.78%) profiles appeared more frequently. No significant associations between the inhibited, introversive, doleful, submissive, dramatizing, forceful, oppositional and self-demeaning profiles and the diagnosis of AN or BN were found.

Finally, based on the categorical perspective, it was analyzed whether the presence of AN or BN might increase the number of personality profiles in a person (considering a cut-off point of BRS > 85) or not. In this regard, the association between the variable "to have/not to have at least one personality profile with BRS scores > 85" and "to suffer from AN or BN" was analyzed by means of the X² test. As a result, the frequency of patients in the AN group having BRS scores > 85 in at least one profile was 65.15%, while in the group of BN that percentage was 55.26%. In the AN group, 28.78% of patients had a unique profile with BRS scores > 85, 22.72% showed scores > 85 in two profiles, 9.09% in three profiles and 4.54% showed BRS scores > 85 in four personality profiles. In the case of the BN group, 28.94% had a personality profile with BRS scores > 85, 18.42% showed two profiles with BRS scores > 85 and 7.89% had three profiles with BSR scores > 85. Any significant associations between the variable "to have/not to have at least one personality profile with BRS scores > 85" and "to suffer from AN or BN" (X2; [1] = 0.996, p > 0.05) were found.

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to analyze possible differences with respect to personality profiles (considering the mean scores in each of those profiles) between AN and BN groups. A second objective was to analyze the frequency of patients presenting each personality profile in both AN and BN groups. Finally, a third objective was to explore whether there were some associations between the diagnostic groups and the presence of specific personality profiles. This is one of the few studies based on the personality profiles of adolescents with ED since most of the published studies have focused their research on adult populations.

Bearing in mind the differences in personality profiles between patients with AN and BN, from a dimensional point of view, significant differences in the following profiles were found: submissive, egotistic, unruly, forceful, conforming, oppositional, self-demeaning, borderline and tendency to impulsivity.

Specifically, AN patients show a more submissive profile, with higher egotistic and conforming levels. On the contrary, BN patients show higher scores on the following traits: unruly, forceful, oppositional, self-demeaning and borderline.

In general, previous research reports a higher frequency of personality disorders of cluster B among BN patients, the most frequent one being the borderline PD and ranging 34-40% (29,30). Another study reported that obsessive personality is one of the most common features among AN patients (mainly restrictive type) (31). These previous results would confirm our findings, having obtained a significant difference in the conforming (obsessive) and borderline profiles. The unruly (antisocial), forceful (sadistic), oppositional (passive-aggressive) and self-demeaning (self-destructive) scale, which also appear higher in our group of BN patients, could be related to different pathologies included in the cluster B of PD, thus confirming previous findings (3,4,6).

With regards to the frequency of the personality profiles in this study, one of the results we highlight is that the most prevalent AN profiles are conforming, egotistic and histrionic.

Following the Millon's theory, the conforming profile could be assimilated to obsessive traits or, at high levels, to the characteristics of the obsessive-compulsive PD as described in the DSM (5). Therefore, our results are consistent with those studies reporting that the obsessive traits are characteristic of AN patients (32).

Considering frequency, the second profile showed in our AN group is the egotistic personality. Once again, following Millon's theory, this personality is parallel to the narcissistic personality of the DSM. Therefore, our findings do not agree with some previous research, suggesting that narcissism is a core characteristic of BN (33).

Regarding the histrionic profile, our results seem to disagree with others which have found an increased frequency of PD of cluster B (histrionic) in BN (6) or those studies which have pointed out that histrionic personality is more characteristic of BN (31). Therefore, previous research seems to emphasize that the histrionic personality is more related to BN, whereas in our sample of AN, this type of personality is the third in order of prevalence, followed by conforming and egotistic. The discrepancy between our results and those reported in previous research could be explained by the limitations of the categorical perspective. This categorical perspective is clinically useful, but data are affected by vagueness and not homogeneous criteria for PD. On the contrary, the dimensional analysis performed in the current study does not force categorizing and permits a more comprehensive analysis of the relative strength of personality traits in the different ED subtypes.

With regards to personality profiles in BN, the most prevalent in our sample are the unruly, the submissive and the borderline. Millon found that those individuals scoring high in unruliness usually show the typical appearance, temperament and behavior of the antisocial PD of the DSM. Studies generally report the cluster B of DSM as the most frequent in the case of BN, including the antisocial personality, this being less prevalent than the borderline type (30,31).

The submissive profile is also quite common in our sample of BN. Millon suggests that submission is parallel to the dependent PD of the DSM. These findings seem to be different from those previously reported, in which the dependent personality is related to AN (34).

There seems to be a consensus about the fact that the most common PD among BN patients is the borderline type, ranging between 9 and 40% of cases according to different authors (30,35). In this case, our results confirm this usual finding.

Finally, regarding the analysis of the presence of personality profiles in AN and BN, which could become dysfunctional, our results indicate no significant associations between the two diagnostic groups and the presence of personality profiles with high BRS scores. These results do not coincide with previous studies in adolescents which have reported a higher prevalence of PD in AN (36), or with previous findings in adults emphasizing a higher prevalence of PD in BN (4). No relationships among the different subtypes of ED have been found in our sample. At the same time, our results show the presence of various personality profiles in each participant. Nevertheless, a different frequency of personality profiles in each ED subtype is confirmed, as it has been previously mentioned.

To sum up, despite the consistent research with respect to the different personalities in AN and BN patients, the core of the link between personality and ED remains unclear. Millon updated his personality and PD theory considering more evolutionary, phylogenetic and human development-based principles (23). The evolutionary model (evolution-based theory) consists of four basic poles apart in order to describe the different personality prototypes. These poles are: a) pleasure-pain polarity; b) active-passive polarity; c) self-other polarity; and d) thought-feeling polarity. Based on these polarities Millon builds a classification system (taxonomy). Prototypes of personality may be strong, weak or neutral considering each specific element of the classification (37). Our results, by means of the Millon's theory, show that the differences found between AN and BN are based on differences related to the adaptation styles (active-passive polarity). AN patients have a more submissive profile (dependent), egotistic (narcissist) and conforming (compulsive). All of them were conceptualized by Millon as passive types of personality with regards to adaptation, thus leading to a passive accommodation. On the contrary, in the case of BN patients higher scores in the following profiles were found: rebel (antisocial), eruptive (sadistic), oppositional (passive-aggressive), intropunitive (self-destructive) and borderline. Apart from the self-destructive type, the rest of profiles tend to use an active adaptation so intervening in one's surrounds. In our opinion, the self-destructive style might score higher in cases of BN due to the presence of purging behaviors and its relationship with self-injurious characteristics of this type of personality. Considering the borderline profile, Millon considers a polarity between active and passive attitudes when dealing with the environment, resulting dysfunctional bearing in mind the adaptation polarity.

With regards to the active-passive polarity, the differences found between AN and BN in our study could be related to the neurobiological differences between the different ED subtypes. It must be noted that neurobiological vulnerabilities have a relevant contribution in the pathogenesis of AN and BN. Several studies consider that alterations in neural serotonin modulation contribute to dysphoric temperament, which in turns implies an emotional disturbed regulation as well as disturbances in the rewarding circuitry. Consequently, these patients would be at higher risk for ED (38).

This work should be considered as an exploratory initial one in order to systematize and organize some relevant variables. Some limitations of this study are: a) the use of a self-reported personality assessment; b) the shortage of specific research on adolescent populations, which prevents us from comparing our results with other similar ones; and c) the possible influence of the patients' clinical status on the evaluation of personality characteristics.

New studies in adolescent populations are required in order to confirm these preliminary findings. Henceforth, it would be more appropriate to use larger samples in order to compare the results obtained by the MACI with those obtained by means of clinical interviews. In addition, other variables should be taken into account to improve the analyses (e.g., different coping strategies) (39). Finally, it would be appropriate to include nutritional status assessment at the moment of personality evaluation. It is also important that future studies include groups of different diagnostic categories (restrictive vs purging types of ED) and a longitudinal (prospective) design.

An important contribution of this study is the clinical relevance of eating symptoms, at least in relation to the personality traits, which in some cases become maladaptive and interfere with the treatment of these patients. Longitudinal studies support the relevance of personality subtypes in order to classify ED due to the importance of assessing personality characteristics aimed to better identify bad prognostics. In addition, it is useful to orientate therapeutical interventions (19). Therefore, the assessment of personality profiles (active/passive) in both AN and BN might support the selection of the most effective treatments in order to regulate the polarity balances. Considering our results, AN patients should modify their passive reactions towards the environment with more active strategies (for example, by means of problem solving strategies) while in the case of BN patients treatment should focus on more passive adaptation strategies (for example, decreasing impulsive behaviors and promoting abstract thinking).

Finally, there are several studies which report a correlation between the clinical recovery of PD and a better course of ED (40). Therefore, it is possible to construct a theoretical structure in order to perform more adequate therapeutic programs considering the specific needs of each type of ED in adolescents, taking into account the different clinical and personality profiles.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

1. Espelage DL, Mazzeo SE, Sherman R, Thompson R. MCMI-II profiles of women with eating disorders: A cluster analytic investigation. J Personal Disord 2002;16(5):453-63. [ Links ]

2. Jáuregui Lobera I, Santiago Fernández MJ, Estébanez Humanes S. Trastornos de la conducta alimentaria y la personalidad. Un estudio con el MCMI-II. Aten Primaria 2009;41(4):201-6. [ Links ]

3. Turner BJ, Claes L, Wilderjans TF, Pauwels E, Dierckx E, Chapman AL, et al. Personality profiles in eating disorders: Further evidence of the clinical utility of examining subtypes based on temperament. Psychiatry Res 2014;219(1):157-65. [ Links ]

4. Pérez IT, Del Río Sánchez C, Mas MB. MCMI-II borderline personality disorder in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psicothema 2008;20(1):138-43. [ Links ]

5. Millon T. Manual of Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory. Minneapolis: National Computer System; 1993. [ Links ]

6. Martín PM, Motos A, Del Águila E. Personalidad y trastornos de la conducta alimentaria: un estudio comparativo con el MCMI-II. Rev Psiquiatr Psicol Niño Adolesc 2001;1:2-8. [ Links ]

7. Marañón I, Echeburúa E, Grijalvo J. Are there more personality disorders in treatment-seeking patients with eating disorders than in other kind of psychiatric patients? A two control groups comparative study using the IPDE. Int J Clin Heal Psychol 2007;7(2):283-93. [ Links ]

8. Bruch H. Island in the river: The anorexic adolescent in treatment. Adolesc Psychiatry 1979;7:26-40. [ Links ]

9. Strober M. Personality and symptomatological features in young, nonchronic anorexia nervosa patients. J Psychosom Res 1980;24(6):353-9. [ Links ]

10. Bulik CM, Beidel DC, Duchmann E, Weltzin TE, Kaye WH. Comparative psychopathology of women with bulimia nervosa and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1992;33(4):262-8. [ Links ]

11. Casper RC, Hedeker D, McClough JF. Personality dimensions in eating disorders and their relevance for subtyping. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992;31(5):830-40. [ Links ]

12. Cassin SE, Von Ranson KM. Personality and eating disorders: A decade in review. Clin Psychol Rev 2005;25(7):895-916. [ Links ]

13. Fassino S, Pierò A, Gramaglia C, Abbate-Daga G. Clinical, psychopathological and personality correlates of interoceptive awareness in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and obesity. Psychopathol 2004;37(4):168-74. [ Links ]

14. Harrison A, O'Brien N, López C, Treasure J. Sensitivity to reward and punishment in eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 2010;15;177(1-2):1-11. [ Links ]

15. Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Masters K. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(12):2215-21. [ Links ]

16. Connan F, Campbell IC, Katzman M, Lightman SL, Treasure J. A neurodevelopmental model for anorexia nervosa. Physiol Behav 2003;79(1):13-24. [ Links ]

17. Vitousek K, Manke F. Personality variables and disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol 1994;103(1):137-47. [ Links ]

18. Steiger H, Bruce K. Personality traits and disorders in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. In: Brewerton T, ed. Clinical handbook of eating disorders: An integrated approach; 2004. pp. 207-28. [ Links ]

19. Thompson-Brenner H, Eddy KT, Franko DL, Dorer DJ, Vashchenko M, Kass AE, et al. A personality classification system for eating disorders: A longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry 2008;49(6):551-60. [ Links ]

20. American Psychiatric Association. APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Text Revision; 2000. [ Links ]

21. Liley LJ, Watson HJ, Seah E, Priddis LE, Kane RT. A controlled study of personality traits in female adolescents with eating disorders. Clin Psychol 2013;17(3):115-21. [ Links ]

22. Millon T. Modern psychopathology. A biosocial approach to maladaptative learning and functioning. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1969. [ Links ]

23. Millon T. Toward a new personology: An evolutionary model. New York: Wiley; 1990. [ Links ]

24. Castro J, Toro J, Salamero M, Guimerá E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Validation of the Spanish version. Evaluación Psicológica 1991;7(2):175-89. [ Links ]

25. Garner DM, Garfinkel PE. The Eating Attitudes Test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 1979;9(2):273-9. [ Links ]

26. Henderson M, Freeman CP. A self-rating scale for bulimia: The "BITE." Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:18-24. [ Links ]

27. Moya TR, Bersabé R, Jiménez M. Fiabilidad y validez del Test de Investigación Bulímica de Edimburgo (BITE) en una muestra de adolescentes españoles. Psicol Conductual 2004;12(3):447-61. [ Links ]

28. Aguirre G. Adaptación española del MACI. Inventario clínico para adolescentes de Millon. TEA Ediciones: Madrid; 2004. [ Links ]

29. Attie I, Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC. A developmental perspective on eating disorders and eating problems. In: Lewis M, Miller SM, eds. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 409-20. [ Links ]

30. Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Weltzin TE, Kaye WH. Temperament in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1995;17(3):251-61. [ Links ]

31. Wonderlich SA, Swift WJ, Slotnick HB, Goodman S. DSM-III-R personality disorders in eating-disorder subtypes. Int J Eat Disord 1990;9(6):607-16. [ Links ]

32. Anderluh MB, Tchanturia K, Rabe-Hesketh S, Treasure J. Childhood obsessive-compulsive personality traits in adult women with eating disorders: Defining a broader eating disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(2):242-7. [ Links ]

33. Johnson CL. Treatment of eating-disordered patients with borderline and false-self/narcissistic disorders. In: Johnson CL, eds. Psychodynamic treatment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. pp. 165-93. [ Links ]

34. Marcos YQ, Cantero MCT, Acosta GP, Escobar CR. Trastornos de personalidad en pacientes con un trastorno del comportamiento alimentario. An Psiquiatr 2009;25(2):64-9. [ Links ]

35. Díaz M, Carrasco JL. La personalidad y sus trastornos en la anorexia y en la bulimia nerviosa. In: E. García-Camba, ed. Avances en trastornos de la conducta alimentaria anorexia nerviosa, bulimia nerviosa, obesidad. Barcelona: Masson; 2001. pp. 93-106. [ Links ]

36. Bottin J, Salbach-Andrae H, Schneider N, Pfeiffer E, Lenz K, Lehmkuhl U. Persönlichkeitsstörungen bei jugendlichen Patientinnen mit Anorexia und Bulimia nervosa. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 2010;38(5):341-50. [ Links ]

37. Millon T, Davis R. Trastorno de la personalidad: conceptos, principios y clasificación. Trastornos de la personalidad. Más allá del DSM-IV. Barcelona: Masson; 1998. [ Links ]

38. Duvvuri V, Bailer UF, Kaye WH. Altered serotonin function in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. In: Müller CP, Jacobs BL, eds. Handbook of the behavioral neurobiology of serotonin. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2010. pp. 715-29. [ Links ]

39. Jáuregui-Lobera I, Estébanez S, Santiago-Fernández MJ, Álvarez-Bautista E, Garrido O. Coping strategies in eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2009;17(3):220-6. DOI: 10.1002/erv.920. PMID: 19274619. [ Links ]

40. Grilo CM, Pagano ME, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG, et al. Natural course of bulimia nervosa and of eating disorder not otherwise specified: 5-year prospective study of remissions, relapses, and the effects of personality disorder psychopathology. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(5):738-46. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Belén Barajas Iglesias.

Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa.

Av. San Juan Bosco, 15.

50009 Zaragoza, Spain.

e-mail: belenbarajas@hotmail.com

Received: 14/02/2017

Accepted: 26/03/2017