Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Nutrición Hospitalaria

versión On-line ISSN 1699-5198versión impresa ISSN 0212-1611

Nutr. Hosp. vol.36 no.6 Madrid nov./dic. 2019 Epub 24-Feb-2020

https://dx.doi.org/10.20960/nh.2324

Original Papers

Veinticinco años de cruce duodenal. Cómo cambiar al cruce

Twenty-five years of duodenal switch. How to switch to the duodenal switch

Twenty-five years of duodenal switch. How to switch to the duodenal switch

INTRODUCTION

Duodenal switch (DS) surgery consists of two operations, vertical gastrectomy (VG) plus biliopancreatic bypass (BPD). DS is the most complex technique in bariatric surgery for morbid obesity (MO). The DS combines restriction of food intake and malabsorption in the small intestine. Scopinaro started the DBP in 1976 (1).

Hess (2) describes it as: a) VG eliminates major gastric curvature, reduces gastric volume, and intake and allows for normal emptying; and b) derives post-pylorus intake from duodenum to ileum, DBP, to cause malabsorption.

Hess (3) recommends measuring the entire small intestine, without tension, from Treitz to ileocecal valve and uses 50% of its proximal length as a bilio-pancreatic loop (BPL), 10% distal as a common loop (CL) and 40% of the intermediate length as digestive loop (DL).

Marceau (4,5) made standard DBP until 1991 and then switched to DS and is the first author to publish it (6) in 1993 as parietal gastrectomy plus DBP.

Lagacé (7) reported the first good results of the DS in 61 patients in 1995 and Marceau in 1998 (8) compared 252 DBP with distal gastrectomy and 465 DS with an operative mortality of 1.7%.

Hess (9) and Baltasar (10 11 12 13 14 15 16-17) describe the gastric part of the operation as vertical gastrectomy (VG) and creation of a gastric tube (GT). Anthone (18) and Almogy (19) called it longitudinal gastrectomy and Rabkin (20), gastrectomy of the greater curvature.

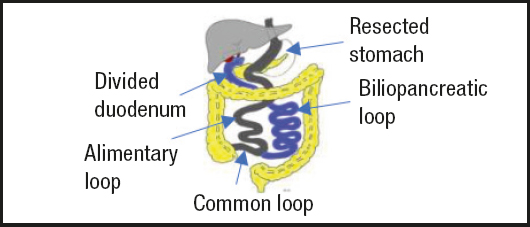

The DS (21 22 23 24 25-26) became standardized in the 1990s (Fig. 1). Hess (9) modified the procedure by intussusception and suturing the serosa of the VG in the following 188 cases to reduce the incidence of leakage at the staple line. Ren (27) made the first complete LDS in July 1999 and Baltasar (28) made the first LDS in Europe in 2000 (29). Paiva (30) in Brazil and Scopinaro (31) in Italy made the first standard laparoscopic DBP in 2000.

Quetelet reported the use of body mass index (BMI = kg/m2) to measure weight results, but after reviewing 7,410 patients, our mathematician (32) developed the concept of predictive BMI (PBMI) taking as a control an initial BMI (IBMI) greater than 25.

The percentages of lost weight loss (%EWL) are not the same in a subject with MO grade 2 as in a subject with triple obesity (TO), and thus we only measure BMI in excess of 25. %EWL would then be the predictive BMI = BMI x 0:4 + 11.75. This concept has already been used positively by others (33) (Fig. 1).

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

Open duodenal switch (ODS) by laparotomy

The patient is placed in Trendelenburg’s forced position. The operation is performed by three surgeons through a transverse supraumbilical incision between both costal margins (Fig. 2A and B). Once in the abdomen, the round and falciform ligaments are severed and the gallbladder and appendix are removed.

The entire intestine is measured starting distally, from the ileocecal valve, and the common loop (CL) is marked as 10% of the intestine. The alimentary loop (AA) corresponds to 40% of the most proximal bowel and is divided with a linear stapler. The proximal 50% is the biliopancreatic loop (BPL) and begins in the proximal duodenum, D1. The AA distal to the junction with BPL and the AC joined by a jejune-ileal anastomosis (JIA) with continuous monoplane absorbable suture, and the mesenteric defect is closed with a non-absorbable suture.

The stomach is exposed, and a 12 mm nasogastric tube is introduced as a guide to the lesser curvature. The major gastric curvature is devascularized with ultrasonic scalpel from 3 cm distal to the pylorus to the angle of His. The entire major gastric curvature is devascularized with ultrasonic scalpel from 3 cm distal to the pylorus up to the angle of His. The stomach is divided sequentially with staplers from pylorus to the esophagus-gastric junction and removed including the major gastric curvature. In the minor curvature, the gastric tube (GT) remains, which is reinforced with continuous invaginated suture and includes the separate omentum and both gastric walls, to avoid torsion and leakage.

A retro duodenal tunnel is created, distal to the right gastric artery, and the duodenum is divided at D1 with a linear stapler. An inverted suture reinforces the duodenal stump.

The proximal AA passes retro colic on the right and a duodenum ileal anastomosis (DIA) is performed with continuous resorbable suture. The operation has four suture lines (gastric reinforcement, ADI, AYR and the distal duodenal stump). Two drains are placed, one next to the GT and the other in the DIA.

The abdominal incision is closed in two layers with continuous Maxon. After weight loss, the scar length is reduced to one third (Fig. 2B) and allows the abdominoplasty edge to reach the pubic area (Fig. 2C). We started the ODS on March 17th, 1994 and the average surgical time was 91 minutes.

Laparoscopic duodenal switch (LDS)

It is also performed by a team of three surgeons. Six ports are used. An Ethicon #12 optical trocar enters the abdomen, under vision, at the lateral edge of the right rectus muscle, through three fingertips and below the costal margin, and is the main working port. A 10 mm supraumbilical port is used for the midline camera (Fig. 3). The remaining four 5 mm trocars are Ternamian type ones that do not slide. We placed two sub-costal on the right and left, one in the left hypochondrium and one in the epigastrium used to retract the liver. The rest of the procedure is as in the open technique.

All anastomosis is manual monolayer, starting with the self-locking sliding stich of Serra-Baltasar (38,39) and ending with the Cuschieri knot (40). To avoid serous lesions, the entire intestine is measured with forceps marked 5 cm apart. The stomach is removed without a protective bag. A Maxon suture closes the 12 mm port. We started the LDS on September 5th, 2000 (41). The average operating time was 155’ after the first 50 cases.

At discharge, patients received prescriptions with multivitamin complex (Centrum Forte), vitamin A - 20,000 IU, vitamin D - 50,000 IU, calcium carbonate 1,000 mg and ferrous sulfate 300 mg vitamins B1 and B12.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

A total of 950 consecutive MO patients (518 ODS and 432 LDS) were operated on from 1994 to 2011, after full multidisciplinary preoperative evaluation and legal informed consent; 782 were women (82.3%) and 168 were men (17.7%). The average age was 35 years (24-63). Four hundred and seventy-four foreign nationals (376 from the United States, six from Canada, 71 from Norway and 23 from England) were operated on by the same surgical staff in the private clinic.

The average IMCI (kg/m2) was 49.23 (women 49.26 and men 49.07). Obesity range: a) non-severe obesity, grade 2 with comorbidities (IMCI < 40), 110 patients (mean 37.66); b) morbid obese (IMCI 40-50), 464 patients (mean 45.11); c) super-obese (SO) (BMI 50-60), 272 patients (mean 54.32); and d) patients with triple obesity (TO) and IMCI > 60, 104 patients (mean > 66.50) and one patient with IMCI-100 (IMCI-100).

Regarding comorbidities, 115 patients suffered from type 2 diabetes (DMII), 103 from hypertension, five from heart disease, 62 from dyslipidemias, 19 from obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), 16 from osteoarthritis and one from cerebral pseudotumor.

RESULTS

MAIN INTRAOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONSD

Three patients required a tracheotomy for oral intubation failure and severe desaturation, without incidents.

In three patients, the 12 mm gastric tube did not pass beyond the cardias and the stapling of the stomach was done under visual control.

Surgical mortality at 30 days occurred in six ODS patient (1.38%). The causes were: a) leak in DIA: 1; b) leak in AYR, rhabdomyolysis and multiorgan failure: 1; c) pulmonary embolism: 2; d) leak in the duodenal stump: 1; and e) leak in its angle of His: 1. Two LDS patients died (0.38%) by pulmonary emboli. The average mortality of both groups was 0.84%.

POSTOPERATIVE MORBIDITY

Leaks

There were 46 leaks for a total leak rate of 4.84%.

Leaks in the His angle: twenty-one cases (2.3% incidence). They were treated with stenting in ten cases, drainage or laparotomy and Roux-en-Y shunt in three cases. One of the patients died.

Leakage of the duodenal stump: a patient suffered a leak in the duodenal stump that was repaired but died of sepsis. Since then, we protect all stapled duodenal stump with an inverting suture and there have been no further leaks.

ADI leaks: twenty-four cases (2.5% incidence) as it is the most difficult anastomosis. Nineteen of them suffered early leaks, which were successfully treated with drainage or the anastomosis was performed again. Five cases presented late leaks (up to 2-14 years later) and required a new operation and redoing the anastomosis. In one case, the leak occurred three years after surgery, as a gastro pleural fistula, and was treated with total gastrectomy.

RY leakage: a patient had a small bowel diverticulum 100 cm from the ileocecal valve that was removed, and an open RY was performed at the site without incident. There was a new leakage and diagnostic radiological tests did not clarify the cause. With late diagnosis, he was reoperated, suffered rhabdomyolysis, and died.

Pulmonary embolism

Two patients with IBMI-70 and IBMI-65 had embolism despite prophylactic therapy and died. Deep vein thrombosis in one case was successfully treated.

Liver

Liver disorders: twelve patients suffered early alterations in liver function, with significant bilirubin elevations (up to 15 and 29) and resolved with medical treatment.

Liver failure: two patients suffered liver failure (0.2%). The first occurred in a patient six months after surgery; she was included in the liver transplantation urgent list but died in the absence of a donor. The second patient suffered liver failure three years after surgery and received a successful liver transplant plus reversal of BPD. She is healthy four years later. One patient has died 13 years after ODS from alcoholism.

Protein-caloric malnutrition (PCM)

Thirty-three patients (3.3%) developed PCM and 24 required CL lengthening. Thirteen of them were open and without complications. In eleven cases, the CL was lengthened laparoscopically and in two of them the small intestine was injured by the dissection forceps, which were easily perforated by weakness of the wall (Fig. 4). Both leaks were diagnosed intraoperatively and repaired but died later due to new leaks. Multiple mucosal hernias were found in the weak muscle wall between the vessels at the mesentery. These types of hernias have not been previously reported. Therefore, we recommend laparotomy for intestinal lengthening.

Pancreatic-cutaneous fistula: both fistulas and skin lesions healed spontaneously (Fig. 5).

Hypoglycemia: two patients had recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia requiring BPD reversal.

Evisceration: four cases without consequences after adequate repair.

Late intestinal obstruction: seven cases (incidence of 0.73%). We treated two in our unit and the others were treated in other units, with resection of the small intestine.

Beriberi: three cases presented vitamin B1 deficiency with neurological symptoms, gait changes and spontaneous fall. All were successfully corrected. This serious complication requires urgent administration of intravenous B-1.

Fractures: they were due to malabsorption of Ca requiring vitamin D25 plus Ca. Two cases occurred that are asymptomatic after adequate care.

Toxic megacolon: it was due to pseudomembranous colitis 16 years after surgery. The patient required a subtotal colectomy 22 cm from the anus, with terminal ileostomy. Later, the ileum was attached to the rectum.

Miscellaneous: pneumonia (four cases), seroma (four cases), wound infection (15 cases), gastrointestinal bleeding (five cases, three of which require laparotomy) and catheter-related sepsis (three cases).

LONG-TERM MORTALITY

An undiagnosed acute appendicitis occurred at two years and an internal hernia intestinal necrosis at three years. There were other causes of death not related to the DS (cancer, melanoma, myocardial infarction, etc.).

WEIGHT LOSS RESULTS

Final BMI (FBMI) was measured in 60% of 914 patients per year and in 30% at eight years. The mean IMCI of 49.3 fell to an average BMI of 30 (Fig. 6), and the percentage of BMI loss (PPIMC) was 80% at 12 months (Fig. 6).

Figure 6 shows the fall in the average BMI in blue, which fell by about 30, and the % of follow-up in red.

Figure 7 shows, in blue, the expected BMI of 30 and in red, the percentage of predictive BMI depending on the range of the initial BMI and exceeding 100% from 12 months onwards.

Therefore, the %EWL has been excellent in the series and is probably better than with any other obesity operation.

It should be noted that the DS is as effective in super/superobese when the %PIMC Esp is measured as shown in figure 8.

CORRECTION OF COMORBIDITIES

Type II diabetes

The DS is a very effective operation to treat diabetes; 98% of our patients are normoglycemic, with normal glycosylated hemoglobin. Two non-diabetic patients suffered severe hypoglycemic phenomena and the BPD had to be reversed. Hypertension was corrected in 73% of cases and sleep apnea in 100%.

QUALITY OF LIFE

We use the Horia-Ardelt classification (41) of the BAROS scale to evaluate changes in patients’ quality of life. Changes after surgery included: self-esteem, physical activity, social activity, work activity, and sexual activity on a scale from -1 to +1. The average score was 2.03 out of a maximum of three points in 348 patients, which means a significant improvement in their quality of life.

Gastrointestinal symptoms were rated from a minimum of 1 as excellent to a maximum of 5 as very bad. In the 558 patients assessed, food intake of all types was 1.4, vomiting 1.3, appetite 1.96, stool type (from pasty to liquid) 2.2, frequency (from unproblematic to intolerable) 1.8, stool odor 3.35 and abdominal swelling 2.26. Therefore, the sum of all measures was 12.14, for a total score of 5 (excellent) to 35 (poor). The worst side effect was the bad smell of the feces, with an average of 3.35.

DISCUSSION

The DS has never been a popular therapy among surgeons, possibly because of its complexity. Hess (6) describes how after watching a video of us in Seattle-1996, at the ASBS meeting, he modified the procedure with a major curvature suture and had only one leak in 188 cases (17).

Due to its difficulty, very few surgeons continued to make the DS and, in fact, a subdivision was created in the ASBS called “The Switchers”, with its own logo. It remained unpopular and we had to meet, for years, outside the congress venue as a separate group of 25-30 surgeons.

On the contrary, “the switchers” have continued doing the intervention and many patients, even extranational, knew of its advantages and sought this therapy. We have not hidden the difficulties of the operation or, above all, its complications. More than 72 bariatric surgeons visited us and we have intervened live in several national and foreign congresses. Our LDS video was awarded the second prize at IFSO 2002 in Sao Paulo (42). Three patients required an emergency tracheotomy (43,44).

In 2000 we had to use one no removable rigid stent (45) for leaks and then we changed to removable ones (46). Nine patients had required a total gastrectomy (47). In three patients we used a Roux-en-Y diversion shunt (48,49) for the leaks and this is accepted today as the most effective (50).

Liver disorders (51,52) and even failures requiring transplantation (53 54-55) may occur, but also in gastric bypass (56), bronchial fistulas (57) or pancreatic fistulas (58), calorie-protein malnutrition (59) and the need for lengthening (60) to correct them with possible leaks (61) due to herniated defects of the intestinal wall.

At the 2004 consensus conference, Buchwald (62) stated that in OM, ideally, surgery should be considered for patients with obesity above class I (BMI 30-34.9) and associated comorbid conditions. It should have low morbidity and mortality, while providing an optimal and sustained PSP with minimal side effects. No bariatric technique is 100% successful or durable in all patients, nor is there a single standard procedure, and probably never will be. In addition, surgery cannot be the solution for the 1.7 billion OM that populate the earth.

GV leaks are a cause of significant morbidity manifested in the specific GV meetings of Deitel and Gagner (63). Prior to the 1990s, this complication was rare and CD surgeons (switchers) were the first to communicate it. The serosa inverting suture of the line of staples with omentum prevents GT torsion and leakage (13).

The DS is a long and difficult procedure that requires expert and experienced surgeons. Operative mortality should be < 1% and morbidity < 5%. Our LDS mortality is low (0.38%). As patients with DS have four suture lines, early detection of leaks is essential.

Mason (64) called attention to tachycardia as the first warning sign of leakage and no patient should be discharged with tachycardia.

Duncan (65) has discharged more than 2,000 patients early in outpatient surgery programmed without a stay. Our stay after LDS is 2-3 days; we instruct (66) patients to take pulse and temperature digitally and we are notified of these parameters every four hours, for two weeks, in a telematic database. Patients with significant changes in these parameters need immediate and urgent consultation.

DeMaria (67) reported that 450 institutions and 800 surgeons participated in the BSCOE two-year (2007-2009) program. Only 0.89% of the 57,918 patients underwent LDS.

English (68) reports in ASMBS-2016 that obesity has increased alarmingly over the past five decades in the United States, from 13.4% to 36.4% in 2014. The indirect costs of obesity and the overall economic impact are estimated at $1.42 trillion, 8.2% of gross domestic product and more than double defense spending. Obesity is the fifth most important risk factor for mortality in the world. In ASMBS-2016, 215,666 operations were performed in 795 accredited centers (GV: 58.1%) and although 1,187 BPDs were made, only 0.6% were CDs and 26% LDSs.

Nelson (69), using 2007-2010 BOLD data, identified 78,951 patients undergoing GBP or CD. Of these patients, 98% had GBP and only 2% had DS. The DS was associated with longer operating times, blood loss and longer hospital stays. Early reintervention rates were higher in the DS group (3.3% vs 1.5%). BMI drop was significantly higher in DS cases at all follow-up intervals (p > 0.05). In the MO (BMI > 50) there was also a greater fall at two years, 79% DS versus 67% GBP. The improvement in comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension and sleep apnea) was superior with DS (all p < 0.05).

The reintervention rate was 14%. Reviews, including conversions, may soon exceed the number of primary procedures in bariatrics, suggesting the need to develop better evidence-based algorithms to minimize the use of new operations. It is clear that still the number of failures is very high and more effective initial operations are needed.

In 2005, Hess (9) described 1,150 patients with DS and IMCI-50.9. In 15 years there were eight reversals (0.61%) and 37 revisions (3.7%). DMII cured in 98% of patients. The 19 adolescents (aged 14-18 years) improved, advocating for DS as the best operation in adolescents. He also concluded that the DS is a safe and effective operation.

Iannelli (70), in 110 patients with BMI > 50, found a reduction in the rate of postoperative complications when performing two-stage DS. When studying the procedure, only 39 patients (35.5%) required VG and 74.5% of patients avoided BPD.

Biertho (71) made DS in 1,000 patients in 2006-2010. The conversion rate in the laparoscopy group was 2.6%. There was one postoperative death (0.1%) due to embolism. The mean hospital stay was shorter with LDS than with ODS. Complications were 7.5%, with no significant differences.

Biertho (72) treated 566 patients between 2011 and 2015 with LDS with a mean BMI of 49 and no mortality at 90 days. The average hospital stay was 4.5 days. Mayor complications greater in 30 days occurred in 3.0% of patients and minor complications in 2.5%. The %EWL was 81% at 12 months, 88% at 24 months and 83% at 36 months. Patients with HbA1C above 6% decreased from 38% to 1.4%. Readmission was 3.5% and only 0.5% of patients needed a new operation. The short- and medium-term complication rate of LDS is like in any mixed bariatric procedures with excellent metabolic results.

Biron (73) studied the quality of life of 112 patients and 8.8 years follow-up and observed improvement in the disease-specific quality of life in the short and long term.

Prachand (74) observed 152 patients with GBP with %EWL-54% in 198 patients with DS and %EWL-68% and showed that the DS was more effective.

Strain (75) states the DS provides better %EWL than DS in patients with severe obesity. Average weight decreased 31.2% after DS and 4.8% after GBP.

Topart (76.77) performed 83 DS and 97 GBP between 2002 and 2009, with IMCI-55. After three years of follow-up, the average %EWL was 63.7% after GBP and 84.0% after DS (p > 0.0001). Results were significantly better with DS than with GBP.

Våge (78) treated 182 consecutive patients with DS between 2001 and 2008 without 30-day mortality. One patient needed surgery due to one leak, three patients due to bleeding and one due to bile leaks. Six patients (3.2%) underwent surgical BPD revisions, reflecting data similar to ours (3.3%).

Søvik (79) showed better %EWL after DS than with GBP in OM patients. The average BMI decreased 31.2% after GBP and 44.8% after DS.

Angrisani (80) reports in 2018 that 685,874 bariatric operations were performed worldwide; 92.6% were primary interventions, 7.4% were revisions, 96% surgical and 4% endoluminal. They were VG 53.6%, GBP 30.1%, OAGB (single anastomosis gastric bypass) 4.8% and only 1.3% were LDS.

In summary, DS patients consistently reduce BMI more than GBP patients. So why are there so few DS patients?

Rabkin (81) reports that the DS is not associated with extensive nutritional deficiencies. Annual laboratory studies, following any type of bariatric operation, appear to be sufficient to identify unfavorable trends. In selected patients, additional iron and calcium supplements are necessary.

Keshishian (82) performed a preoperative needle liver biopsy on 697 patients with DS. There was transient worsening of AST (13% of baseline, p < 0.02) and ALT (130-160% of baseline, p < 0.0001) up to six months after DS. And he observed a progressive improvement of three degrees in NASH severity and 60% in hepatic steatosis at three years after DS.

TYPE II DIABETES

Buchwald (83) reports that DS and BPD have diabetes resolution rates in excess of 90%. In comparison, the GBP rate is approximately 70%. Tsoli (84) showed that VG was comparable to BPD in DTII resolution but lower in dyslipidemia and blood pressure.

In 2004, Baltasar (85) treated a patient with low BMI-35 with BPD without VG with excellent results at ten years.

Våge (86) thinks that DS is effective in DMII, hypertension and hyperlipidemia and that duration of diabetes and age are the most important preoperative predictors.

According to Eisenberg (87), refractory hyper insulinemic hypo glycaemia after surgery is very rare and its pathophysiology has not yet been fully elucidated. Partial pancreatectomy is associated with significant potential morbidity and should not be recommended. Reversion of BPD is the simplest therapy and the best operation for such hypoglycemia, and we did so for two of the patient samples.

In the staged DS, what part of the operation should be done first? The BPD or VG? Most surgeons recommend doing VG first.

Marceau (88) treated 1,762 patients from 2001 to 2009, all scheduled for DS. As the first stage he treated 48 isolated BPD without VG and 53 VG isolated cases. Long-term %EWL results and resolution of metabolic abnormalities were better with BPD alone than with isolated VG. Full DS %EWL were superior than the two-stage ones. VG and BPD contribute independently to beneficial metabolic outcomes.

Moustarah (89) treated 49 SO patients with BPD without VG. The initial weight was 144 kg and the IMCI was 52.54 kg. The drop in BMI of 14.5 kg/m2 was very significant (p < 0.001).

BPD without VG has rarely been used as a single weight loss procedure, but in patients whose clinical indications justify omission of VG, isolated BPD has better weight loss results. In this series, %EWL at two years compares favorably with other bariatric operations.

The advantage is that BPD without VG is reversible, and VG can be added at any later time. We believe that, with these results in mind, we should do BPD first since it is a totally reversible procedure and easier than VG especially in SSO as it is performed in a lower part of the abdomen. The VG, in addition, can be added more easily later if necessary and at any time.

We should not forget the extraordinarily high participation of Spanish surgeons in the development of BPD techniques. Larrad and Sánchez (90,91) developed a BPD technique and made several very important publications. Thus, did Solano and Resa (92), Ballesteros (93) and Hoyuela (94).

The contribution of Sánchez-Pernaute and Torres (95) of the Hospital Clinic Hospital in making a variant of the LDS with the single anastomosis (SADI) is very important and is also becoming a popular operation worldwide.

A major problem with DS patient follow-up is that other physicians and/or surgeons may not understand how to prevent or treat their long-term complications. DS patients follow-up is very important. Upon discharge, a detailed technical explanation of the operation is provided, as well as an extensive explanatory sheet explaining the laboratory analyses needed for life, each of the possible complications and their correction.

The determination of serum albumin is the most important long-term data for detecting PCM. Monitor PTH and vitamin D25 to detect calcium malabsorption and prevent pathology. Iron deficits should be treated with intravenous Fe.

In addition to leaks, the most serious long-term complication of DS is PCM. Surgical correction is simple by the jejune-jejunal anastomosis technique called “kiss-operation” to lengthen the AC, preferably by laparotomy.

MO patients should receive the DVD at the time of their operation, so that, if a new operation is necessary, the surgeon knows in detail the original technique.

The support of the Endocrinology, Nursing and Nutrition teams is essential throughout the process.

A SWITCH TO THE DUODENAL SWITCH

A wake-up call to switch to the DS

Halawani (96) states that one-third (34.9%) of United States adults are obese. In 2011-2015, the number of LDS in the United States was less than 1%. The LD should be added to the practice of the Centers of Excellence in Obesity (CEO).

DS gives a superior %EWL and has a lower rate of weight recovery. In addition, it is better than GBP, preserves the pylorus and produces slower gastric emptying. With adjustments to the length of the AC and the size of the gastric tube, any obese patient can be a DS candidate.

Patients with BMI < 50 may also be candidates. The DS is a viable option due to its flexibility. The surgeon can adjust the size of the GT and alter the impact of the restriction. The length of the CL can be variable.

The DS is good in chronic patients, who use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids. The early death rate compared with GVL (0.28%) is slightly higher (0.43%), although it is still considered as a complex high-risk procedure and the results should be viewed with caution.

The DS is very versatile and may offer comprehensive management of obesity and its metabolic comorbidities. With dedication, adequate training, and comprehensive education, the CD can be implemented in practice.

CONCLUSIONS

DS techniques are not common for OM management. The DS is the most complex technique and its learning curve is longer than in other operations. To standardize the technique, it took us at least 25 cases in ODS and 50 in LDS. The DS is safe and the most effective in terms of long-term weight loss results.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

All procedures involving human participants were conducted in the studies cited in this document in accordance with the ethical standards of national and institutional research committees and with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies cited.

REFERENCES

1. Scopinaro N, Gianetta E, Civalleri D, et al. Two years of clinical experience with biliopancreatic bypass for obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1980;33:506-14. [ Links ]

2. Hess DS, Hess DW. Biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch. Obes Surg 1998;8:267-82. [ Links ]

3. Hess D. Limb measurements in duodenal switch. Obes Surg 2003;13:966. [ Links ]

4. Marceau P, Biron S, St Georges R, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion with gastrectomy as surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Obes Surg 1991;1:381-7. [ Links ]

5. Marceau S, Biron S, Lagacé M, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion, with distal gastrectomy, 250 cm and 50 cm limbs: long-term results. Obes Surg 1995;5:302-7. [ Links ]

6. Marceau P, Biron S, Bourque RA, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion with a new type of gastrectomy. Obes Surg 1993;3:29-3. [ Links ]

7. LagacéM, Marceau P, Marceau S, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion with a new type of gastrectomy: some previous conclusions revisited. Obes Surg 1995;5:411-8. [ Links ]

8. Marceau P, Hould FS, Simard S, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. World J Surg 1998;22:947-54. [ Links ]

9. Hess DS, Hess DW, Oakley RS. The biliopancreatic diversion with the duodenal switch: results beyond 10 years. Obes Surg 2005;15:408-16. [ Links ]

10. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M. Hybrid bariatric surgery: duodenal switch and bilio-pancreatic diversion. VCR 1996;12:16-41. Disponible en: www.youtube.com/watch?v=3mNnZte3W_I&feature=youtu.be [ Links ]

11. Baltasar M, Bou R, Cipagauta LA, et al. Hybrid bariatric surgery: bilio-pancreatic diversion and duodenal switch - Preliminary experience. Obes Surg 1995;5:419-23. [ Links ]

12. Baltasar A, Del Río J, Bengochea M, et al. Cirugía híbrida bariátrica:cruce duodenal en la derivación bilio-pancreática. Cir Esp 1996;59:483-6. [ Links ]

13. Baltasar A, Del Río J, EscriváC, et al. Preliminary results of the duodenal switch. Obes Surg 1998;7:500-4. [ Links ]

14. Baltasar A, Bou R, MiróJ, et al. Cruce duodenal por laparoscopia en el tratamiento de la obesidad mórbida: técnica y estudio preliminar. Cir Esp 2001;70:102-4. [ Links ]

15. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M, et al. Duodenal switch: an effective therapy for morbid obesity-intermediate results. Obes Surg 2001;11:54-8. [ Links ]

16. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M. Open duodenal switch. Video. BMI 2011;1.5.4(356-9). Disponible en:www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0nTzeUDI5o [ Links ]

17. Baltasar A. Hand-sewn laparoscopic duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:94-6 [ Links ]

18. Anthone G, Lord R, DeMeester T, et al. The duodenal switch operation for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg 2003;238(4):618-28. [ Links ]

19. Almogy G, Crookes P, Anthone G. Longitudinal gastrectomy as a treatment for the high-risk super-obese patient. Obes Surg 2004;14:492-7. [ Links ]

20. Rabkin RA. Concept. The duodenal switch as an increasing and highly effective operation for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 2004;14:861-5. [ Links ]

21. Baltasar A. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a misnomer. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:127-31. [ Links ]

22. Baltasar A. La Real Academia Nacional de Medicina dice…La “Gastrectomía Vertical” es el término correcto. BMI-Latina 2012;2:2-4. Disponible en:www.bmilatina.com [ Links ]

23. Biron S, Hould FS, Lebel L, et al. Twenty years of biliopancreatic diversion: what is the goal of the surgery? Obes Surg 2004;14:160-4. [ Links ]

24. Marceau P, Biron S, Hould FS. Duodenal switch: long-term results. Obes Surg 2007;17:1421-30. [ Links ]

25. Marceau P, Biron S, Hould FS, et al. Duodenal switch improved standard biliopancreatic diversion: a retrospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009;5:43-7. [ Links ]

26. Biertho L, Biron S, Hould FS. Is biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch indicated for patients with body mass index <50 kg/m? Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:508-15. [ Links ]

27. Ren CJ, Patterson E, Gagner M. Early results of laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch: a case series of 40 consecutive patients. Obes Surg 2000;10:514-23. [ Links ]

28. Baltasar A, Bou R, MiróJ, et al. Avances en técnica quirúrgica. Cruce duodenal por laparoscopia en el tratamiento de la obesidad mórbida: técnica y estudio preliminar. Cir Esp 2001;70:102-4. Disponible en:www.youtube.com/watch?v=GSfzgYYxZJ8 [ Links ]

29. Weiner RA, Blanco-Engert R, Weiner S, et al. Laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch: three different duodeno-ileal anastomotic techniques and initial experience. Obes Surg 2004;14:334-40. [ Links ]

30. Paiva D, Bernardes L, Suretti L. Laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion for the treatment of morbid obesity:initial experience. Obes Surg 2001;11:619-22. [ Links ]

31. Scopinaro N, Marinari G, Camerini G. Laparoscopic standard biliopancreatic diversion: technique and preliminary results. Obes Surg 2002;12:241-4. [ Links ]

32. Baltasar A, Pérez N, Serra C, et al. Weight loss reporting: predicted BMI after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2011;21:367-72. DOI:10.1007/s11695-010-0243-7 [ Links ]

33. Molina A, Sabench F, Vives M, et al. Usefulness of Baltasar's expected body mass index as an indicator of bariatric weight loss surgery. Obes Surg 2016;26. DOI:10.1007/s11695-016-2163-7 [ Links ]

34. Baltasar A, Bou R, MiróJ, et al. Laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch: technique and initial experience. Obes Surg 2002;12:245-8. [ Links ]

35. Baltasar A, Bou R, J MiróM, et al. Laparoscopic duodenal switch: technique and initial experience. Chir Gastroenterol 2003;19:54-6. [ Links ]

36. Baltasar A. Video case report. Hand-sewn laparoscopic duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:94-6. [ Links ]

37. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M, et al. Laparoscopic hand-sewn duodenal switch. Video. BMI-Latina 2012;2:11-3. [ Links ]

38. Serra C, Pérez N, Bou R, et al. Sliding self-locking first stitch and Aberdeen knots in suture reinforcement with omentoplasty of the laparoscopic gastric sleeve staple line. Obes Surg 2014;24:1739-40. DOI:10.1007/s11695-014-1352-5 [ Links ]

39. Baltasar A, Bou R, Serra R, et al. Use of self-locking knots in running intestinal bariatric sutures. Glob Surg 2015;2:100-1. DOI:10.15761/GOS.1000132 [ Links ]

40. Cuschieri A, Szabo Z, West D. Tissue approximation in endoscopic surgery: suturing and knotting. Informa Healthcare;1995. ISBN-13:9781899066032 [ Links ]

41. Oria HE, Moorhead H. Updated bariatric analysis and reporting outcome system (BAROS). Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009;5:60-6. [ Links ]

42. Baltasar A, Bou R, MiróJ, et al. Hand sutured laparoscopic duodenal switch V13. V13. Obes Surg 2002;12:483. Disponible en:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=egoBphA1s90 [ Links ]

43. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M, et al. Emergency tracheotomy in morbid obesity. Sci Forschen. Obes Open Access 2017;3(2). DOI:10.16966/2380-5528.132 [ Links ]

44. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M, et al. Difficult intubation and emergency tracheotomy in morbid obesity. BMI-Latina 2013;3:4-7. [ Links ]

45. Baltasar A. Wall-stent prosthesis for severe leak and obstruction of the duodenal switch. Obes Surg 2000;10(2):29. [ Links ]

46. Serra C, Baltasar A, Andreo L, et al. Treatment of gastric leaks with coated self-expanding stents after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 2007;17:866-72. [ Links ]

47. Serra C, Baltasar A, Pérez N, et al. Total gastrectomy for complications of the duodenal switch, with reversal. Obes Surg 2006;16:1082-6. [ Links ]

48. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M, et al. Use of a Roux limb to correct esophago-gastric junction fistulas after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 2007;17:1409-10. [ Links ]

49. Baltasar A, Serra C, Bengochea M, et al. Use of Roux limb as remedial surgery for sleeve gastrectomy fistulas. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008;4:759-63. [ Links ]

50. Mcheimeche H, Dbouk S, Saheli R, et al. Double Baltazar procedure for repair of gastric leakage post-sleeve gastrectomy from two sites:case report of new surgical technique. Obes Surg 2018;28:2092-5. [ Links ]

51. Baltasar A, Serra C, Pérez N, et al. Clinical hepatic impairment after the duodenal switch. Obes Surg 2014;14:77-8. [ Links ]

52. Baltasar A. Liver cirrhosis and bariatric operations. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006;16:579-81. [ Links ]

53. Baltasar A. Liver failure and transplantation after duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:c93-6. [ Links ]

54. Castillo J, Fábrega E, Escalante C, et al. Liver transplantation in a case of steatohepatitis and subacute hepatic failure after biliopancreatic obesity surgery diversion for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 2001;11:640-2. [ Links ]

55. Cazzo E, Pareja JC, Chaim EA. Falencia hepática após derivações bilio-pancreáticas: uma revisão narrativa. Sao Paulo Med J 2017;135. E-pub:10 de noviembre de 2016. DOI:10.1590/1516-3180.2016.0129220616 [ Links ]

56. Ossorio M, Pacheco JM, Pérez D, et al. hepático fulminante a largo plazo en pacientes sometidos a bypass gástrico por obesidad mórbida. Nutr Hosp 2015;32:430-43. [ Links ]

57. Díaz M, Garcés M, Calved J, et al. Gastro-bronchial fistula: long term or very long-term complications after bariatric surgery. BMI-Latina 2011;5:335-7. [ Links ]

58. Bueno J, Pérez N, Serra C, et al. Fistula pancreato-cutánea secundaria a pancreatitis postoperatoria tras cruce duodenal laparoscópico. Cir Esp 2004;76:184-6. [ Links ]

59. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M, et al. Malnutrición calórico-proteica. Tres tipos de alargamiento de asa común. BMI-Latina 2011;5:96-7. [ Links ]

60. Baltasar A, Serra C. Treatment of complications of duodenal switch and sleeve gastrectomy. En: Deitel M, Gagner M, Dixon JB, et al. (eds.). Handbook of obesity surgery. Toronto: FD Comunicación;2010. pp. 156-61. [ Links ]

61. Baltasar A, Bou R, Bengochea M. Fatal perforations in laparoscopic bowel lengthening operations for malnutrition. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:572-4. Disponible en:www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hw_aPYLjGXI [ Links ]

62. Buchwald H. 2004 ASBS. Consensus conference statement bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: health implications for patients, health professionals, and third-party payers. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2005;1:371-81. [ Links ]

63. Dietel M, Gagner M, Erickson AL, et al. Third International Summit. Current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011;7:749-59. [ Links ]

64. Mason R. Diagnosis and treatment of rapid pulse. Obes Surg 1995;3:341. [ Links ]

65. Duncan T, Tuggle K, Larry Hobson L, et al. PL-107. Feasibility of laparoscopic gastric bypass performed on an outpatient basis. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011;7:339-54. [ Links ]

66. Baltasar A. WhatsApp Assistance in bariatric surgery. J Obes Eating Disord 2017;3(1)28. ISSN:2471-8203. DOI:10.21767/2471-8513.100017 [ Links ]

67. DeMaria E, Pate V, Warthen M, et al. Baseline data from American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery - Designated bariatric surgery centers of excellence using the Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:347-35. [ Links ]

68. English W, DeMaria M, Brethauer SA, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States in 2016. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14:259-63. [ Links ]

69. Nelson D, Blair KS, Martin M. Analysis of obesity-related outcomes and bariatric failure rates with the duodenal switch vs gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Arch Surg 2012;147:847-54. [ Links ]

70. Iannelli A, Schneck AS, Topart P, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy followed by duodenal switch, in selected patients versus single-stage duodenal switch for super-obesity: case-control study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:531-8. [ Links ]

71. Biertho L, Lebel S, Marceau S, et al. Perioperative complications in a consecutive series of 1000 duodenal switches. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:63-8. [ Links ]

72. Biertho L, Simon-Hould F, Marceau S, et al. Current outcomes of laparoscopic duodenal switch. Ann Surg Innov Res 2016;10:1. DOI:10.1186/s13022-016-0024-7 [ Links ]

73. Biron S, Biertho L, Marceau S. Long-term follow-up of disease-specific quality of life after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14(5):658-64. Accepted SOARD 3291. [ Links ]

74. Prachand V, DaVee R, Alberdy JA. Duodenal switch provides superior weight loss in the super-obese (BMI >50) compared with gastric bypass. Ann Surg 2006;244:611-9. [ Links ]

75. Strain CW, Gagner M, Inabnet WB, et al. Comparison of effects of gastric bypass and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch on weight loss and body composition 1-2 years after surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:31-6. [ Links ]

76. Topart P, Becouarn G, Salle A. Five-year follow-up after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal Switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011;7:199-205. [ Links ]

77. Topart P, Becouarn G, Ritz P. Weight loss is more sustained after bilio-pancreatic diversion with duodenal switch than Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in super-obese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:526-30. [ Links ]

78. Våge V, Gåsdal R, Lakeland C, et al. The biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch (BPDDS): how is it optimally performed?Obes Surg 2011;21:1864-9. [ Links ]

79. Søvik T, Karlsson J, Aasheim E, et al. Gastrointestinal function and eating behavior after gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:641-7. [ Links ]

80. Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2013. Obes Surg 2015;25:1822-32. DOI:10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z [ Links ]

81. Rabkin R, Rabkin JM, Metcalf B, et al. Nutritional markers following duodenal switch for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 2004;14:84-90. [ Links ]

82. Keshishian A, Zahriya K, Willes EB. Duodenal switch has no detrimental effects on hepatic function and improves hepatic steatohepatitis after 6 months. Obes Surg 2005;15:1418-23. [ Links ]

83. Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2009;122:248-56.e5. [ Links ]

84. Tsoli M, Chronaiou A, Kehagias I. Hormone changes and diabetes resolution after biliopancreatic diversion and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a comparative prospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:667-78. [ Links ]

85. Baltasar A. Historical note: first diabetes metabolic operation in Spain. Integr Obes Diabetes 2015;2:180-2. DOI:10.15761/IOD.1000140 [ Links ]

86. Våge V, Roy M, Nilsen M, et al. Predictors for remission of major components of the metabolic syndrome after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Obes Surg 2013;23:80-6. DOI:10.1007/s11695-012-0775 [ Links ]

87. Eisenberg D, Azagury D, Ghiassi S, et al. ASMBS statement on postprandial hyper-insulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;371-8. [ Links ]

88. Marceau P, Biron S, Marceau S, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion-duodenal switch: independent contributions of sleeve resection and duodenal exclusion. Obes Surg 2014;24:1843-9.DOI:10.1007/s11695-014-1284-0 [ Links ]

89. Moustarah F, Marceau S, Lebel S, et al. Weight loss after duodenal switch without gastrectomy for the treatment of severe obesity: review of a single institution case series of duodeno-ileal intestinal bypass. Can J Surg 2010;53(4):S51. [ Links ]

90. Larrad A, Moreno B, Camacho A. Resultados a los dos años de la técnica de Scopinaro en el tratamiento de la obesidad mórbida. Cir Esp 1995;58:23-2. [ Links ]

91. Larrad A, Sánchez-Cabezudo C, De Cuadros Borrajo P, et al. Short-, mid- and long-term results of Larrad biliopancreatic diversion. Obes Surg 2007;17:202-10. [ Links ]

92. Solano J, Resa JJ, Fatas JA, et al. Derivación bilio-pancreática laparoscópica para el tratamiento de la obesidad mórbida. Aspectos técnicos y análisis de los resultados preliminares. Cir Esp 2003;74(6):347-50. [ Links ]

93. Ballesteros M, González T, Urioste A. Biliopancreatic diversion for severe obesity:long-term effectiveness and nutritional complications. Obes Surg 2016;26:38-44. DOI:10.1007/s11695-015-1719-2 [ Links ]

94. Hoyuela C, Veloso E, Marco C. Derivación bilio-pancreática con cruce duodenal y su impacto en las complicaciones posoperatorias. Cir Esp 2006;80(Supl 1):1-250 175. [ Links ]

95. Sánchez-Pernaute A, Rubio M, Torres A, et al. Proximal duodenal-ileal end-to-side bypass with sleeve gastrectomy: proposed technique. Obes Surg 2007;17:1614-8. DOI:10.1007/s11695-007-9287-8 [ Links ]

96. Halawani HM, Antanavicius G, Bonanni F. How to switch to the switch:implementation of biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch into practice. Obes Surg 2017;27(9):2506-9. DOI:10.1007/s11695-017-2801-8 [ Links ]

Received: November 26, 2018; Accepted: May 10, 2019

texto en

texto en