INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a public health problem in our country, with increasing morbidity and mortality (1). Living kidney donors are a population potentially at risk of developing CKD (2,3). Initial studies showed the apparent safety of kidney donation (4); however, subsequent studies have revealed that the donation process is an independent risk factor that increases the probability of developing CKD (2). It is recognized that the presence of metabolic syndrome (MS) and cardiometabolic risk factors (CMFRs) increase the risk of CKD HR: 1.30 (95 % CI, 1.24-1.36) (5); OR: 2.48 (95 % CI, 1.33-4.62) (6); OR: 1.43 (95 % CI, 1.18-1.73) (7). This risk has also been demonstrated in kidney donor patients in which the presence of MS was associated with an increased risk of developing CKD (8).

Renal transplantation is the treatment of choice for preserving quality of life in patients with CKD (1,2). When considering renal donors, it is essential to carry out protocols for evaluating short- and long-term risks associated with the immediate nephrectomy procedure and future possible development of CKD (7,8). According to the Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors, some absolute contraindications for LKD are glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, candidates with IgA nephropathy, donor candidates with active malignancy, donor candidates with kidney disease that causes kidney failure, pregnancy, and an albumin excretion rate greater than 100 mg/dL (13). However, the opinion of the Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors regarding candidates for living kidney donation with diabetes mellitus, MS, obesity, or hypertension are permissive and leave decision-making regarding the acceptance or rejection of donors with these comorbidities open to clinical judgment and the individual circumstances of the cases involved (14).

Based on these guidelines, some hospitals with renal transplantation programs have chosen to be permissive and accept kidney donors with CMRFs or even MS, leaving the treatment for these alterations undescribed not only before donation but also after donation, with no emphasis on any follow-up protocol to correct these alterations.

From our perspective, if donation is an independent risk factor for the development of CKD, the additional presence of metabolic syndrome and CMRFs in kidney donors increases the probability of developing CKD. Based on the above, the objective of this study was to describe changes in CMRFs and MS over time in LKD. The findings generated by this study will be used to establish a checklist for use in transplant programs regarding the selection, evaluation, and follow-up criteria for living kidney donors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

This was a retrospective cohort study in LKD to identify the presence of CMRFs and MS over time. Clinical, biochemical, and anthropometric parameters registered in the medical records at the time of donation and at the last visit at the outpatient clinic were evaluated. Medical records of LKD were reviewed from April 2010 to December 2015. All medical records that had complete information and a follow-up of at least 6 months after donation were included in the study. Medical records with incomplete information or with less than 6 months of follow-up after donation were excluded. The study was carried out according to the STROBE principles, performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and approved by the hospital's Ethics and Research Committee with the registration number DI/16/105B/03/065.

OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS OF VARIABLES

The CMRFs considered in this study were serum glucose concentrations ≥ 100 mg/dL; triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL; and body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 (to define overweight) or ≥ 30 kg/m2 (to define obesity) according to the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO). High systolic blood pressure (SBP) was defined as SBP between 120 and 129 mmHg, and high diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was defined as DBP ≥ 80 mmHg, according to the American Heart Association (15). The diagnosis of MS was made according to the modified criteria of the Adult Treatment Panel III (16) considering the presence of three or more of the following criteria that were taken from the data available in the medical records: 1) fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL; 2) triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; 3) SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg; and 4) obesity or overweight according to BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (17). We also analyzed variables that are known to be associated with CMRFs: tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption, and uric acid ≥ 6.8 mg/dL. The presence or absence of a family history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or CKD was recorded. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula, and a GFR of 90-130 mL/min/1.73 m2 was considered a normal value.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

According to the data distribution, media and standard deviations or media and interquartile ranges were used, categorical variables were reported in absolute numbers and frequencies, and the Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test was used to compare differences.

Paired Student's t-tests were used to compare changes in the CMRFs and MS in the same donor over time before nephrectomy. In the secondary analysis, we used univariate logistic regression to describe the association of CMRFs and MS with GFRs less than 90, 70 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. A 95 % CI and two-sided p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF KIDNEY DONORS

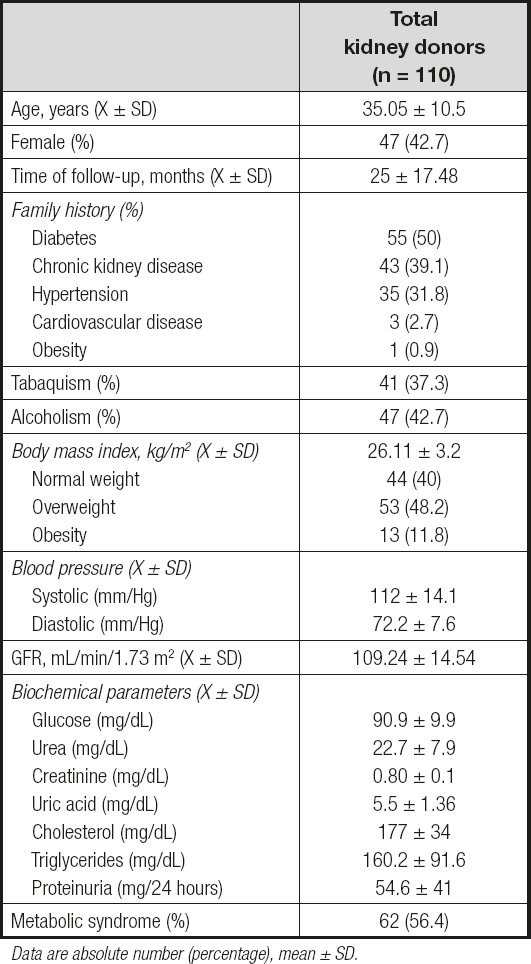

The study included 63 (57.3 %) men and 47 (42.7 %) women with a mean age of 35.05 ± 10.5 years (Table I). Patients were followed for 25 ± 17.48 months after nephrectomy. In terms of family history, 50 % of the subjects reported relatives with diabetes; 39.1 % had a history of kidney disease; 31.8 % had a history of systemic arterial hypertension; 2.7 % had a history of heart disease; and 0.9 % had a history of obesity. Similarly, 37.3 % of patients had a history of tobacco use, and 42.7 % had a history of alcohol consumption. With an average BMI of 26 ± 11 kg/m2, 40 % of patients had a normal weight, 48.2 % had overweight, and 11.8 % had obesity, according to the WHO criteria. Regarding blood pressure, mean SBP was 112 ± 14.1 mmHg, and mean DBP was 72.2 ± 7.6 mmHg. Among biochemical parameters a mean glucose of 90.9 ± 9.9 mg/dL, triglycerides of 160.2 ± 91.6 mg/dL, and serum creatinine of 0.8 ± 0.1 mg/dL were observed. In terms of metabolic syndrome 62 patients met the criteria of MS prior to nephrectomy (56.4 %).

CHANGES IN BODY MASS INDEX AND IN CLINICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL PARAMETERS IN KIDNEY DONORS DURING FOLLOW-UP

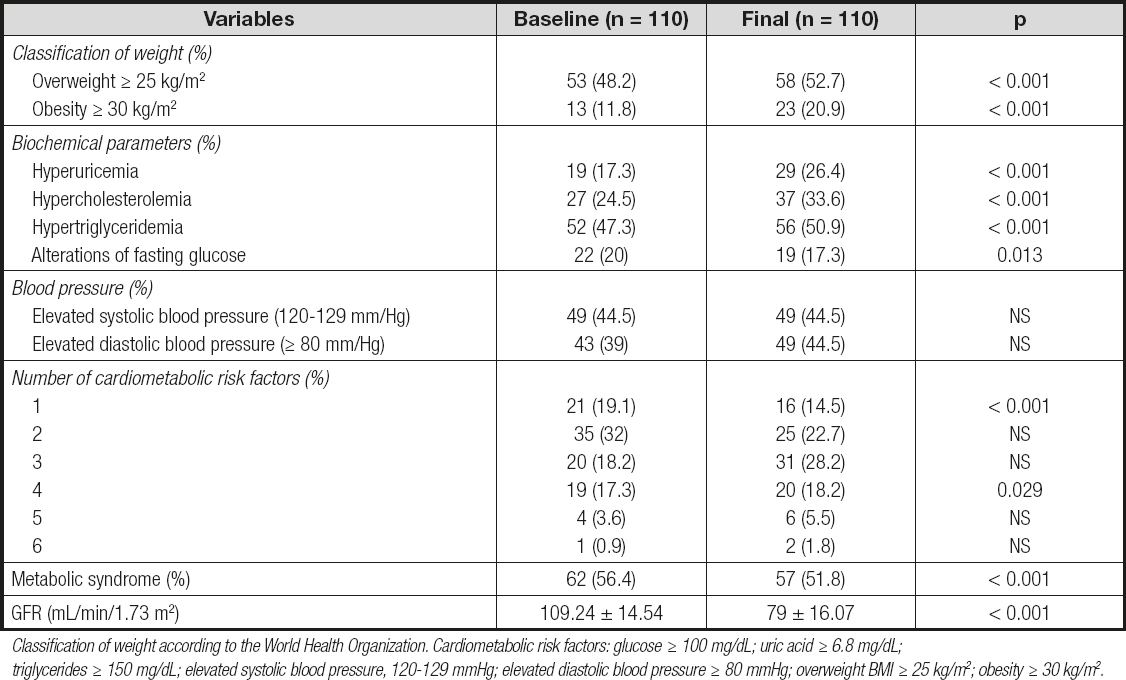

The paired comparison between baseline and final BMIs showed significant differences, with an increase in the percentage of donors who were overweight (48.2 % to 52.7 %, p < 0.001) or obese (11.8 % to 20.9 %, p < 0.001) (Table II).

Table II. Changes in body mass index, clinical and biochemical parameters in kidney donors during follow-up

Classification of weight according to the World Health Organization. Cardiometabolic risk factors: glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL; uric acid ≥ 6.8 mg/dL; triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; elevated systolic blood pressure, 120-129 mmHg; elevated diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mmHg; overweight BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2; obesity ≥ 30 kg/m2.

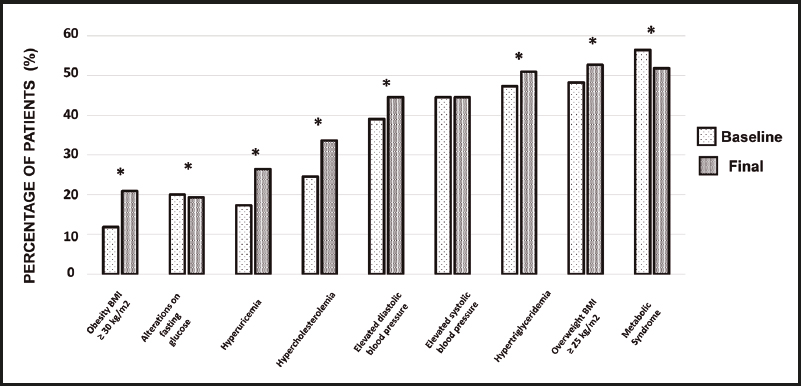

Regarding biochemical parameters, the percentage of patients with hyperuricemia increased from 17.3 % to 26.4 % (p < 0.001), that of subjects with hypercholesterolemia increased from 24.5 % to 33.6 % (p < 0.001), and the percentage of patients with hypertriglyceridemia increased from 47.3 % to 50.9 % (p < 0.001), with a statistically significant decrease in patients with fasting glucose alterations. Before donation, 19.1 % of patients had at least one risk factor; 32 % had two factors; 18.2 % had three factors; 17.3 % had four factors; 3.6 % had five factors; and 0.9 % had six factors. At the end of follow-up there was a significant decrease in patients with one or two risk factors, and a significant increase in patients with four risk factors was observed (Table II). A reduction in the percentage of patients with metabolic syndrome from 56.4 % to 51.8 % (p < 0.01) was also observed. On the other hand, in the evaluation of GFR a significant decrease was observed from 109.24 mL/min/1.73 m2 to 79 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p < 0.01) across the entire patient population. The percentage of change for each cardiometabolic factor between baseline and the end of follow-up is shown in figure 1.

ASSOCIATION OF CARDIOMETABOLIC RISK FACTORS WITH DECREASED GLOMERULAR FILTRATION RATE

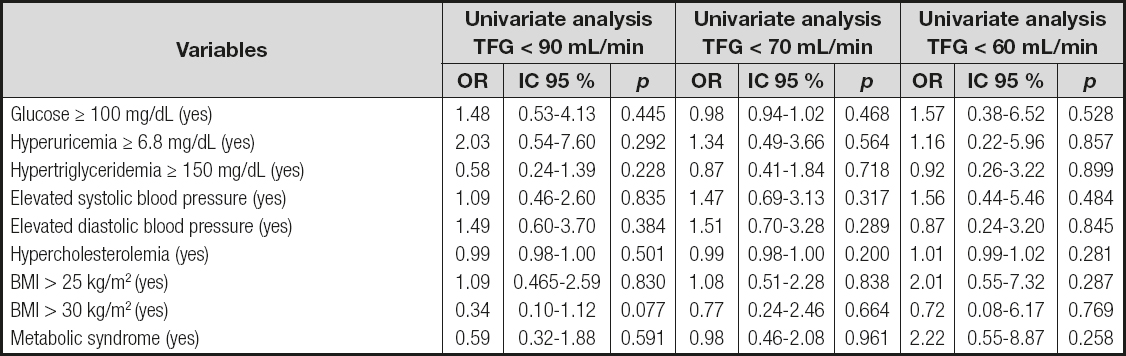

At the end of follow-up the following was documented: eleven patients with GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; fifty-seven patients with GFR < 70 mL/min/1.73 m2; and eighty-two patients with GFR < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2. In the univariate logistic regression analysis there was no association between CMRFs and decreased GFR (Table III).

DISCUSSION

Our results show a high number of LKD with one or more CMRFs and MS before and after nephrectomy. Likewise, at the end of follow-up a significant increase in patients with a single CMRF, such as overweight, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hyperuricemia, or hypertriglyceridemia, was documented, and we also observed an increase in the combination of 3, 4, 5, and 6 CMRFs. Although we observed a decrease in the percentage of patients with MS, their frequency was still greater than 50 %.

The Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors with respect to candidates for living kidney donation with diabetes mellitus, MS, obesity, or hypertension are permissive and leave decision-making open to clinical judgment and individual circumstances. No consensus exists on the acceptance or rejection of a donor who suffers from these comorbidities or who may have more than one CMRF, and only one recommendation exists for those specifically diagnosed with MS (13).

In 2005, in the Amsterdam Forum, it was established that individuals with a family history of diabetes or with a diagnosis of diabetes should not be donors due to the potential risk of developing diabetic nephropathy (4). The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends a systematic review of the risk of developing DM, such as: 1) family history of type-2 diabetes mellitus; 2) obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2); 3) alcohol consumption; 4) black, Andean or Native American individuals; 5) hypertension; 6) dyslipidemia; and 7) age over 40 years (18). However, despite these recommendations our study identified LKD with a positive family history of diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertriglyceridemia. Likewise, a significant increase in LKD with obesity and overweight was documented at the end of follow-up.

It has been established that overweight and obesity are risk factors for the development of kidney disease (19). In a cohort of 2,585 patients who have been monitored since 1978, it was found that for each unit of standard deviation of BMI, obesity increased the risk of developing kidney disease by 23 % (20). In the same way, Hsu et al., after adjusting for variables such as blood pressure and diabetes mellitus, reported that the risk of developing advanced chronic kidney disease increased proportionally with BMI (21). Therefore, in overweight subjects the risk for CKD was 1.87; for patients with class-1 obesity the risk was estimated at 3.57; for patients with type-2 obesity the risk was 6.12; and for patients with extreme obesity the estimated risk reached 7.07 (21). On the other hand, Whan et al. found that in overweight patients the risk of developing hypertension was 1.30, and in patients with obesity it was 1.50 (22).

Our study allowed us to identify that 44.5 % of the subjects already had elevated systolic blood pressure according to the new classification of the American Heart Association. Hypertension is a well-established and independent risk factor for the development of CKD (23). The study by Shulman et al. showed that 5.9 % of the participants in the Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program had serum creatinine levels greater than or equal to 1.5 mg/dL, while 2.3 % of 8,683 patients with repeated serum creatinine measurements had a significant loss of renal function at 5 years of follow-up (24). In addition to the above, our study allowed us to document a high frequency of hyperuricemia after donation. Hyperuricemia has been established as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease due to preglomerular arteriopathy and tubulointerstitial inflammation (25).

Our study also revealed a high frequency of renal donors with metabolic syndrome. Studies have associated MS with an increased risk of CKD. A meta-analysis published in 2003 by Thomas et al. (31) identified that MS increased the risk of having a GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 by up to 55 %. Other studies have reported how MS increases the risk of CKD from 30 % (5) to 88 % (26). Similarly, the individual components of MS, such as elevated blood pressure, hypertriglyceridemia, and impaired fasting glucose, were associated with an increased risk of loss of renal function (27). Likewise, as more of the components of MS become present, the risk for CKD also increases (27). The study by Feng Sun et al. observed that the presence of one CMRF increased the risk of developing CKD by 14 %, while the presence of five components increased the risk by 2.72 times (5).

In this paper we identified a decrease in the GFR expected for LKD. However, the inferential analysis between risk factors and the decrease in GFR did not reveal a greater association between the presence or number of CMRFs and the presence of MS; however, there is clear evidence that this association can be observed from the third or fifth year of follow-up (28-32). A Mexican study published by Cuevas-Ramos et al. evaluated the impact of MS on GFR in renal donors. The study showed that the presence of MS before nephrectomy was an independent risk factor that increased the risk of having a GFR < 70 mL/min/1.73 m2 by 2.2 times (8). On the other hand, the meta-analysis by Thomas et al. analyzed eleven prospective studies and revealed that MS and its components were significantly associated with an increased risk of developing CKD (27). Based on all the above, our results show a high percentage of LKD with CMRFs and MS.

The strategies established to date do not seem to improve CMRFs, so it is important to change and strictly supervise other strategies for modifying lifestyles and habits in LKD in order to modify CMRFs and reduce the frequency of MS. Studies have shown efficacy in reducing the progression of kidney damage with the application of strategies to improve CMRFs (29). Mexico currently has a high frequency of MS (30). With inadequate nutritional habits and sedentary lifestyles (31) the Mexican population has diets characterized by high sodium load, refined carbohydrates, and processed foods (31-33).

Although the study protocol for LKD in our hospital requires patients with MS to have multidisciplinary evaluations in nutrition, endocrinology, and internal medicine to reduce their body weight, it is the Transplant Committee who conditions the donation-to-be until the LKD has demonstrated a change in lifestyle and a significant decrease in body weight. Unfortunately, our results suggest that, in general, LKD resume lifestyles that favor the development of overweight, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.

With a donation rate of 22 transplants per million inhabitants (34), our country needs an increased donation rate to address the high incidence of patients with kidney disease (9). However, our results suggest that we need standardized protocols for LKD that are more stringent and consider excluding patients with CMRFs and MS due to the clear association with the development of kidney disease in other studies. This should be accompanied by a federal policy from the Ministry of Health that favors deceased donor programs. The rate of deceased donors in our country is insufficient (34). Although there are advances in legislative policies with laws that favor universal donation, there are still barriers that limit deceased donor processes such as a poor culture of donation; the limited infrastructure of hospitals, which cannot carry out procurement processes; no tissue banks; an insufficient number of transplant surgeons, and a complicated distribution and allocation system for organs, tissues, and cells (35). All these barriers must be addressed if deceased donor rates are to be improved and the number of living renal donors is to be reduced in our country.

We need to consider the different limitations of the present study. First, we could not use the definition for MS offered by the Adult Treatment Panel III, and we used different criteria according to the available data recorded in the medical records; and second, we analyzed the data of a small sample size. In conclusion, our study reveals a high percentage of LKD with CMRFs and MS, which is perhaps a reflection of a public health problem in our country. It is shown that after nephrectomy, there is an increased incidence of obesity and overweight in addition to other CMRFs. We must evaluate kidney donation protocols and consider stricter criteria in the selection of LKD, emphasizing follow-up protocols to address CMRFs and MS, accompanied by promotion of an infrastructure policy that favors deceased donor programs.