INTRODUCTION

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is a broad term that includes epithelial malignancies occurring in the lip, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and paranasal sinuses (1). The location of the tumor, along with other factors, including the inflammatory status or the application of anticancer measures (e.g., surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy) exposes HNC patients to a high risk of malnutrition (2).

The available literature suggests that malnutrition is associated with worse quality of life (3-5), an essential part of cancer treatment to maximize the patient's sense of well-being. For this reason, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) designed the Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) as to obtain a validated tool to assess quality of life in cancer patients, taking into consideration physical, emotional, social and functional factors (6).

Despite the importance of nutritional status in HNC patients, nutritional support according to the medical treatment of the HNC is not always uniform or well-defined. The established guidelines for post-operative nutrition, including the recommendations for EN when patients are unable to achieve adequate oral intake, mainly address the early post-operative period rather than the months following surgical intervention. Information regarding the use of EN in the months following surgery, especially in HNC patients, is still limited (7).

To the best of our knowledge, no data relating the quality of life to the type of nutritional treatment of Italian HNC patients who underwent surgical intervention are available in the literature. Therefore, the aim of this cross-sectional study was to evaluate the nutritional status and the quality of life of HNC patients in the post-operative phase undergoing different nutritional support.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY POPULATION AND NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT

Fifty-four patients with HNC who underwent surgical intervention and were referred to the Unit of Clinical Nutrition of the Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy were included in this cross-sectional study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the local Ethics Committee approved study. All patients underwent clinical examination, in which weight was measured with a TANITA BC-410 scale and height using a stadiometer. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Nutritional biochemical parameters were assessed through conventional laboratory methods. Each patient also received dietary counselling from dietitians; total energy and protein intake were calculated according to the 2021 European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines on clinical nutrition in cancer, which recommends fulfilling energy requirements ranging between 25 and 30 kcal/kg/day and protein intake above 1 g/kg/day and, if possible, up to 1.5 g/kg/day. Lastly, patients answered the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire evaluating their quality of life (8).

QUALITY OF LIFE ASSESSMENT

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a validated questionnaire used in international clinical trials to assess the quality of life of cancer patients. The QLQ-C30 version 3.0 is currently the standard version of the QLQ-C30 and should be used in all new studies, unless investigators wish to maintain compatibility with an earlier version of the QLQ-C30 (9).

The validated questionnaire includes five functional scales, three symptom scales, a global health status/quality of life (QoL) scale and six single item measures. Every multi-item scale comprises a diverse set of items, with no repetition amongst scales. All scales and single-item measures have a score ranging from 0 to 100. A high score for a functional scale represents a healthier level of functioning, a high score for global health status/QoL represents better quality of life, whereas a high score for a scale/symptom item represents a higher presence of symptoms/problems.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 28.0 Macintosh program. The results are expressed for parametric data as mean ± standard deviation while for non-parametric data as median and range. The Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric data was used to compare individual groups while the Chi-squared test was used to compare percentages. The values p < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study population comprised fifty-four patients (32 males; 22 females) with a median age of 69 (range: 57-77 years) years. All participants were clinically evaluated for the nutritional status over a median period of two months (range: 1-4) after the surgical intervention. Mean body weight at the nutritional evaluation was 61.8 ± 9.7 kg with a mean BMI of 22.4 ± 3.2 kg/m2. Five patients (9.3 %) were classified as underweight and 14 (25.9 %) as overweight. In terms of nutritional support, 26 patients (48.1 %) were fed through total EN, while the remaining (n = 28) were admitted to the nutritional evaluation only with oral nutrition (ON). ON participants received oral nutritional supplements (ONS) when dietary intake did not cover all nutritional needs. In addition, EN patients were on percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), due to the estimated mean time of use.

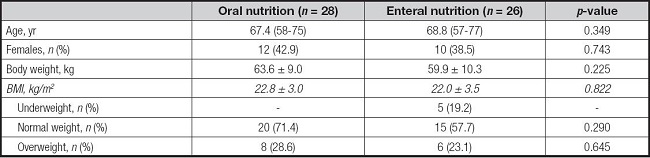

When dividing patients by type of nutritional support (ON vs EN) no significant differences were found for demographic and clinical nutrition parameters (Table I). As expected, all of the underweight patients were on EN.

Table I. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to the nutritional support.

*Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation or number and percentage (%), as appropriate.

BMI: body mass index.

NUTRITIONAL STATUS

Significant differences were found between ON and EN patients for several biochemical parameters of nutrition risk (Table II).

Table II. Laboratory values according to the nutritional support.

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

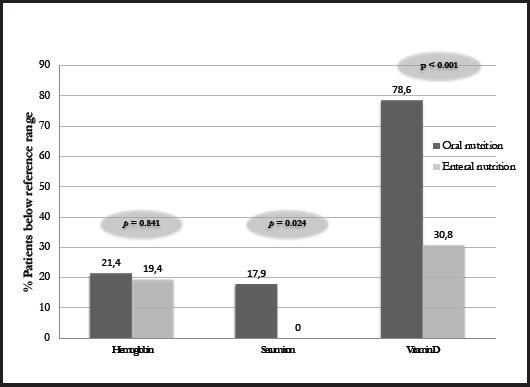

In fact, higher levels of hemoglobin, lymphocytes, iron, folic acid, and vitamin D levels were observed in EN patients with respect to those on. A higher percentage of patients on ON were found to be below the reference limits for hemoglobin and significantly for serum iron and vitamin D compared to patients on EN, indicating a better nutritional profile of patients who were undergoing an EN support (Fig. 1).

QUALITY OF LIFE ASSESSMENT

The EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire, developed to assess the quality of life in cancer patients, was submitted to all the patients at admission. Patients on EN had a higher mean score on Global Health Status/QoL (63.8 ± 17.6) than those on ON (55.4 ± 20.3), although the difference was not significant. Furthermore, when asked “How would you rate your general health status during the last week?”, which was one of the questions used to assess global health status, significantly (p < 0.001) higher scores were found for EN patients (5.1 ± 1.3) compared to those on ON (4.1 ± 1.3). On the other hand, no significant differences were found according to the nutritional support in relation to symptom scale scores, including some highly nutrition-related symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, constipation, or diarrhea. However, it is noteworthy that ON patients had lower scores, meaning less symptomatology, on the items of nausea and vomiting (4.2 ± 11.7 vs 9.0 ± 14.3), dyspnea (9.5 ± 17.8 vs 14.1 ± 23.4) and loss of appetite (15.5 ± 16.8 vs 23.1 ± 22.6) than EN patients. In fact, a higher percentage of ON patients reported having no symptoms related to dyspnea compared to EN patients (75 % vs 69.2 %) (p = 0.636), loss of appetite (53.6 % vs 42.3 %) (p = 0.407), and significantly for vomiting (100 % vs 76.9 %) (p = 0.007). Moreover, ON patients had a higher score for diarrhea (10.7 ± 25.7), in comparison with EN patients (7.7 ± 23.7) indicating that participants on EN had a lower presence of diarrhea symptoms compared to those on ON.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study conducted in HNC Italian post-operative patients aimed at evaluating nutritional status and quality of life in the post-operative phase with EN or ON support. EN patients reported higher levels of hemoglobin, lymphocytes, iron, folic acid and vitamin D than those on ON, suggesting a better nutritional status. In addition, patients on EN seem to have a better quality of life, as they had higher mean QoL scores and reported significantly higher scores for the question pertaining to general health status as compared to the ON group. However, this difference should not be evaluated in isolation as patients with ON reported less symptoms of nausea or dyspnea compared to patients with EN, although the differences found were not statistically significant.

HNC patients are at high risk of malnutrition due to several factors that may hinder food intake, commonly leading to weight loss that may be accompanied by alterations in key biochemical parameters. Malnourished patients usually present with anemia, which can increase symptoms of fatigue, weakness, dizziness and even shortness of breath (10). In our study, ON patients reported lower hemoglobin, iron and folic acid, with around 20 % showing iron levels below the reference ranges, while all patients on EN had levels within the reference range. This finding is in line with the literature, in which enteral support in patients undergoing various medical therapies (11-13) was associated with improved nutritional status. Other studies of the same context, such as that of Löser et al., revealed higher hemoglobin levels in well-nourished people with respect to malnourished HNC patients (14). Similarly, Capuano et al. found a significant correlation between weight loss, low hemoglobin values and systemic inflammation in HNC patients (15).

Another usual biochemical alteration in malnourished patients is vitamin D deficiency. In the present study, we reported that more than half of the patients had low vitamin D levels, reaching almost 80 % of patients treated with ON compared to 30 % of patients treated with EN, in line with what Orell-Kotikangas et al. (16) reported in HNC patients. Low vitamin D levels have been reported to affect efficacy of medical therapies, being involved in the immune system and acting a key role for the maintenance of optimal health status, especially in cancer patients. Hence, it is extremely important to maintain normal circulating levels. Another biochemical parameter that is often taken into account to assess nutritional status in these patients is albumin, although its efficacy is much debated in the literature as it is a parameter sensitive to inflammatory status. Despite the growing interest in albumin in HNC patients undergoing surgery due to its possible association with post-surgical complications and survival (14,17), no significant differences were observed for albumin levels between patients on EN and ON in our sample, with no patients being below reference values.

As far as quality of life is concerned, HNC patients have an impaired quality of life due to complications related to surgical and medical treatments, and the deteriorated quality of life is one of the factors that most undermines medical treatment. It is widely recognized that the nutritional status of cancer patients can influence their quality of life, being malnourished patients those with a worse quality of life (3-5). However, the scientific evidence to determine which nutritional support is most appropriate depending on the patient's treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery) is still limited due to the heterogeneity of the samples of the available studies. In our study of post-operative HNC patients, EN patients reported better quality of life, as measured by the total score of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire, than patients with ON, although the difference was not statistically significant. This finding is in line with other previous studies, such as that of Van Bokhorst-de Van der Schuer et al., who reported that EN improved the quality of life of HNC patients despite they have included only severely malnourished patients who began EN support in the pre-operative period (18). But in contrast, Rogers et al. reported a worse quality of life associated with long-term use of EN in HNC survivors who had previously undergone surgery (19). With regard to the results of items relating symptoms, a lower percentage of ON patients experienced nausea and vomiting, dyspnea and loss of appetite as compared to EN patients. Such reduced reporting of symptoms can be explained, for nausea and vomiting, to a lack of tolerance to EN or continuous EN for several hours, these being the most common side effects of this type of nutritional support (20), and for dyspnea, by the possible association with another clinical condition such as dysphagia in patients with EN compared to those receiving ON, despite not all the available studies are in accordance with this hypothesis (14,21,22).

The study has several limitations that need to be taken into account. First, this is an observational study in which only one measurement of exposure and outcome was made, so it does not allow us to infer causality or rule out residual confounding factors, nor can we rule out the probability of chance findings. Second, our sample comprised a limited number of subjects and needs to be expanded. In addition, important factors that could influence the main results, such as body composition, type of treatment or other risk factors related to HNC were not considered. However, the present study has the strength of having included all HNC patients who underwent surgery after diagnosis of cancer and may provide new evidence on the most appropriate method of nutritional support in the post-operative period for these patients, although further research is needed to optimize nutritional support in these patients.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, although the use of EN should be evaluated in each patient due to possible side effects or complications, especially in case of long-term use, our study suggests that in post-operative HNC patients the use of EN could have a positive effect on the nutritional status and quality of life of these patients. Considering malnutrition as an important factor for the well-being of these patients, more research is needed to better understand the optimal nutritional support for HNC patients in the post-operative phase.