My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Anales de Psicología

On-line version ISSN 1695-2294Print version ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.29 n.2 Murcia May. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.2.148251

Theoretical proposals in bullying research: a review

Propuestas teóricas en la investigación sobre acoso escolar: una revisión

Silvia Postigo, Remedios González, Inmaculada Montoya and Ana Ordoñez

Department of Personality, Evaluation and Psychological Treatments, University of Valencia

ABSTRACT

Four decades of research into peer bullying have produced an extensive body of knowledge. This work attempts to provide an integrative theoretical framework, which includes the specific theories and observations. The main aim is to organize the available knowledge in order to guide the development of effective interventions. To that end, several psychological theories are described that have been used and/or adapted with the aim of understanding peer bullying. All of them, at different ecological levels and different stages of the process, may describe it in terms of the relational dynamics of power. It is concluded that research needs to take this integrative framework into account, that is to say to consider multi-causal and holistic approaches to bullying. For the intervention, regardless of the format or the target population, the empowerment of the individuals, and the social awareness of the use and abuse of personal power are suggested.

Key words: Bullying; peer violence; theoretical framework; review.

RESUMEN

Cuatro décadas de investigación sobre acoso entre iguales han conseguido un extenso cuerpo de conocimientos. Este trabajo pretende ofrecer un marco teórico integrador que incluya las teorías y observaciones específicas realizadas hasta el momento. El objetivo es organizar los conocimientos disponibles para orientar en el desarrollo de investigaciones/intervenciones eficaces. Para ello se describen las diversas teorías psicológicas que se han utilizado y/o adaptado para comprender el acoso, en relación a las variables más relevantes. Dichas teorías específicas, muestran el acoso en diferentes niveles ecológicos y momentos del proceso, y pueden describirlo en términos de dinámicas relacionales de poder. Se concluye la necesidad de investigar teniendo en cuenta este marco teórico integrador, que considera la multicausalidad y la perspectiva holística del acoso. En la intervención, cualquiera que sea su formato o población objetivo, se sugiere procurar el empoderamiento de los individuos y la concienciación social en cuanto al uso y el abuso del poder personal.

Palabras clave: Bullying; violencia entre pares; marco teórico; revisión.

Introduction

Peer harassment has always occurred, but over the last few decades of the twentieth century there was an increased amount of research due to the necessary changes in social attitude, as evidenced by a simple bibliometric analysis (Figure 1). Since then, an important body of knowledge has been built up, making it possible to find exercises of meta-analysis (Card & Hodges, 2008; Card, Stucky, Sawalami, & Little, 2008; Cook, Williams, War, Kim, & Sadek, 2010; among others) and review (Salmivalli, 2010; Stassen, 2007; among others) in recent literature. However, some myths about bullying, which need to be corrected, persist in our societies, such as that it is "something normal", "makes you stronger" or that the best option is "to ignore the bully" (Stassen, 2007) . Similarly, in science it is necessary to carry out a reflection which not only focuses on observations and results, but also on the psychological theories that support or can support them (e.g. Rigby, 2004; Sánchez, Ortega & Menesini, 2012). Rarely, isolated theories or data can provide the necessary framework with which it is possible not only to understand a complex reality, but to change it. Thus, this paper aims to summarize the theories that, implicitly or explicitly, underlie the most relevant and consistent observations about bullying, integrating them into a comprehensive framework that can guide both the research and development of effective interventions. However, before starting this work it is necessary to dwell briefly on the definition of the phenomenon.

Harassment situations were defined as those in which a student is exposed, repeatedly and over time, to negative actions carried out by another student or group (Olweus, 1993). The starting point of current international research is a more precise and relatively accepted definition of bullying, which considers it as: a) a subtype of violence, physical and/or psychological, that is intentional and systematic, and not provoked by the victim, b) a relationship of dominion/submission, or asymmetric power relationship, characterized by an imbalance of power between the bully, who abuses his power, and the victim, who cannot stop the aggressions (Carrera, DePalma, & Lameiras, 2011; Ombudsman, 2007; Salmivalli, 2010; Stassen, 2007). However, there are three basic problems with this definition, which directly affect the study of the incidence, and indirectly, the study of the causes and consequences of harassment. These problems are related to linguistic and cultural differences, the perception of the students, and the study of the different types of aggression.

Linguistic and Cultural Differences

The term "peer harassment" encompasses a broad and complex reality, also known as school harassment, peer victimization, or bullying. The early research distinguished bullying behavior carried out by a group (mobbing) from that produced by a single individual (bullying) (Olweus, 1993), a distinction that today is ignored. Internationally, but not without some controversy (see Carrera et al., 2011), the term "bullying" now groups the studies on peer harassment or victimization, as shown in databases such as the American Psychological Association Database. However, the differing terms that name this reality in different countries may be considered as not only linguistic differences, but cultural, describing similar phenomena with a different incidence rate (Nansel et al., 2004) and local features (Carrera et al., 2011; Lee, 2011).

Perceptions of Parents, Teachers and Students

Bullying, as identified by researchers, differs -qualitatively and quantitatively- from that of parents, teachers and especially students, who tend to perceive a lower incidence rate, not to distinguish between forms or types of aggression, and/or to exclude those types that are more indirect in nature (Carrera et al., 2011; Law, Shapka, Hymel, Olso, & Waterhouse, 2012, Stassen, 2007). Therefore, the first step in any intervention should be to inform and raise awareness of the nature of bullying, placing particular emphasis on covert forms of aggression.

Types of Aggression

From a phenomenological point of view, the aggressions can be classified by following two criteria that give 6 types (Table 1). The first relates to the nature of aggression, which can be physical, verbal and/or relational. The second concerns the possibility of identifying the perpetrator, which establishes a continuum between direct or overt, and covert or indirect aggressions.

It has been important to distinguish between types of aggression, because it has made the covert forms of aggression visible. Regarding this, significant age and sex-related differences have been observed which indicate that: a) physical aggressions are the least frequent and decrease with age, while verbal and indirect aggressions are more common and may increase or remain stable with age (as they depend on social cognitive development) (Ombudsman, 2007; Cerezo & Ato, 2010; Merrell, Buchanan, & Tran, 2006; Stassen, 2007); and b) boys tend to use more physical aggression than girls, who use more indirect or relational forms of aggression (Ombudsman, 2007; Hess & Hagen, 2006; Postigo, Gonzalez, Mateu, Ferrero, & Martorell, 2009; Stassen, 2007).

However, it is also true that physical and relational aggressions tend to take place together (Card et al., 2008), and that their causes and specific correlates are not well known yet. In addition, bullying literature often interchanges the terms "indirect", "relational" and even "social" aggression, which are similar but not the same, as some studies suggest (Archer & Coyne, 2005; Card et al., 2008; Merrell et al., 2006). Finally, there are other current types of aggressions that have not been included in this categorization, which possibly encompass several categories, given their diffuse limits and nature. These aggressions, included in the term cyberbullying occur outside the school, by using social networks (e.g. Facebook, Twitter or Tuenti) and any electronic device (mobile phone, email or Messenger, among others) (Garaigordobil, 2011). Currently under increasing investigation, they seem to be similar to other traditional forms of harassment, at least in terms of the personal characteristics and stability of the roles involved and their consequences (Aoyama, 2010; Law et al., 2012). Nevertheless, their incidence rate seems to be higher, while the influence of age and sex seems to be lower (Aoyama, 2010; Garaigordobil, 2011; Tokunaga, 2010).

Integrative Theoretical Model

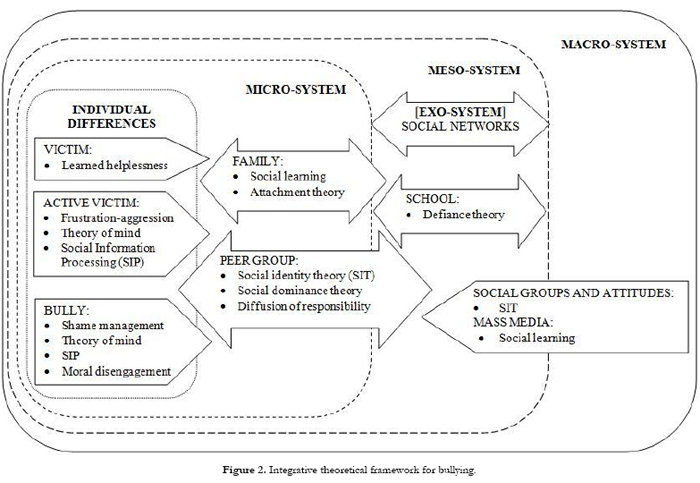

Two broad theories and many more specific ones have been used to study and intervene in peer harassment. They can be grouped together. The two broad theoretical models which have been applied to the study of bullying are: a) the contextual-ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1987), which sorts almost every variable with an influence on bullying into increasing ecological levels of inclusiveness, and seems to provide an adequate explanation of harassment in different cultures (Lee, 2011); and b) the transactional model of development (Sameroff, 1987), which emphasizes the reciprocity between personal and contextual factors in any developmental event, including peer bullying (Boulton, Smith, & Cowie, 2010; Gendron, Williams, & Guerra, 2011; Georgiu & Fanti, 2010). Integrating these two theoretical models makes it possible to create a global framework in which every specific theory can be dealt with (Figure 2). These specific theories explain the influence and interaction of different variables, and can also be grouped according to their underlying process: restorative, developmental or group processes. The following sections summarize these theories and some of the related variables, from the individual to the macro-contextual ecological level, taking into account the type of underlying process.

Individual Differences

Most of the variance in the phenomenon of victimization and harassment by peers appears to be due to individual differences (Lee, 2011; Salmivalli, 2010). The personal characteristics (and deficits) of victims and bullies has been one of the most widely studied areas of bullying. These studies point to two types of explanations: harassment derives from restorative processes carried out by the victim and the bully who has an aggressive personality, and/or harassment, like other forms of social behavior, stems from a developmental process of learning (Table 2).

Restorative Processes

Learned helplessness (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978) is the most widely used theory with which to explain the reaction of the typical victim. This type of passive victim responds submissively to violence, and exhibits mild assertive behavior and low levels of self-esteem and dominance (Card & Hodges, 2008; Cook et al, 2010; Estevez, Martinez, & Musitu, 2006; Olthof, Gossens, Vermande, Aleva, & van der Meulen, 2011). Their greatest handicap when facing up to the aggression lies in their isolation from the peer group (Cerezo & Ato, 2010; Newman, Holden, & Nelville, 2005; Salmivalli, 2010), and their lack of emotional regulation skills (Sánchez et al., 2012). Submitted to the constant terror of not knowing when, how or why the next attack will occur, they tend to blame themselves, feel ashamed, develop feelings of hopelessness, and end up withdrawing from the group that excluded them. Without social support, they can only compensate for the direct effects of violence by surrendering control.

In contrast, the active victim responds to violence with violence, so that is also called provocative or aggressive victim, victimized aggressor, or bully-victim. The dynamics of this role is explained by the frustration-aggression model (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939; Tam & Taki, 2007), wherein the effect of violence is compensated for by transferring the arousal provoked by the insult or humiliation to other circumstances or against others, that is to say by bullying others. They show a combination of the behavior and characteristics of the passive victim and the bully (Card & Hodges, 2008; Cook et al, 2010; Unnever, 2005) and represent a minority, but high risk group, due to their personal characteristics, the severe psychological suffering, and the great likelihood of their being involved in bullying during various stages of their time at school (Burk et al., 2011).

As far as the bullies are concerned, it has been suggested that they would try to obtain, through the dominion/submission relationship, the sense of proficiency they lack in other areas or forms of behavior, which are considered as risk factors (Lam & Liu, 2007; Salmivalli, 2010; Stassen, 2007). For example, they can compensate for a low academic and family self-concept by building a good physical and social self-concept that stems from aggression (Estevez, Martinez, & Musitu, 2006; Laible, Carlo, & Roesch, 2004). However, these processes fail to provide a full explanation for their behavior, and there is adverse evidence for such a causal relationship (Boulton et al., 2010).

Other restorative processes are proposed by the shame management theory (Ahmed, Harris, Braithwaite & Braithwaite, 2001), and restorative justice (Morrison, 2006), which have been studied in different cultures. These theories place the origins of the aggressions in the primitive moral reasoning of the bully, who is not completely conscious of the harm caused to the victim. From this reasoning, the bullies justify their aggression by projecting their own shame onto the victim, which is considered as a moral emotion related to personal identity (Ahmed and Braithwaite, 2006). From this theoretical context, it has been observed that bullies who learn to recognize their shame in a constructive way, instead of projecting it, tend to desist from violence (Ahmed, 2006). Moreover, this kind of explanation may be related to group processes described by the social identity theory (Tajfel, 1984) -which is explained below-, since identity and its related shame can be derived from membership of a low prestige social group. Likewise, this theory agrees with the socio-cognitive theories -which are outlined below- by emphasizing the influence of moral emotions, such as shame, on the bullying phenomenon.

Developmental processes

These processes and their related theories attempt to explain the aggressions of both the bully and the bully-victim, considering them as forms of learned social behavior mediated by socio-cognitive processes. For example, the theory of mind (Premack & Woodruff, 1978) highlights the role of empathy, pointing out that empathy and bullying mutually and negatively predict each other (Stavrinides, Georgiu, & Theofanus, 2010). The bully and his followers have developed their theory of mind, inferential abilities or cognitive empathy, but show deficits in moral and emotional aspects of empathy (Gini, Albiero, Benelli, & Altoé, 2007; Laible et al., 2004). The result is morally disengaged behavior, so they can imagine and predict the effects of the aggression but not feel them with the victim (Ortega, Sánchez, & Menesini, 2002), make external and exculpatory attributions of causality (Avilés & Monjas, 2005), and experience feelings of pride rather than guilt or shame (Sánchez et al., 2012). It should be noted here that there are gender differences in the content of causal attributions, so that female victims are considered more provocative, and the male, more cowardly (Postigo et al., 2009).

The social information processing model (Crick & Dodge, 1994) has distinguished between reactive and proactive aggression. The first is in line with the frustration-aggression model (Dollard et al., 1939) cited above, and describes vengeful aggressions resulting from a misinterpretation of social information, a perception of ambiguous signals as threats, and attributions of hostility. This generates an intense emotion of anger that, in the absence of sufficient self-control, gives rise to the aggression (Calvete & Orue, 2010). In contrast, proactive aggression arises from social learning processes (Bandura, 1973), that is from modeling the cognitive processing that emphasizes aggressive behavior as being more effective than others, in which the individual feels less competent. These aggressions are not provoked, but instrumental, intentional and deliberate, so they do not need elicitors, but are reinforced by the satisfaction (pride) (Calvete & Orue, 2010). This type of aggression is learned, but from whom? Answering this question involves analyzing other ecological levels, because the individual differences fall short of providing a full explanation of harassment.

Micro-system of bullying

The micro-system of bullying refers to the immediate contexts in which the child or adolescent is directly involved (Figure 2). These contexts are mainly the family system, whose influence is explained by developmental processes, and the peer group, whose study refers to the notion of bullying as a group phenomenon (mobbing) (Table 3). However, from this ecological level, bullying may also be explained in terms of the interpersonal relationship (Garcia, 1997). This description emphasizes the negotiation and complementation of the mental models of bully and victim, which refer to the mental state, the self-concept and the characteristic style of information processing.

Developmental Processes: The family system

The theories that describe the influence the family has on bullying are the social learning model (Bandura, 1973), which would explain the modeling of violence and asymmetrical power relationships through exposure to them; and the attachment theory (Bowlby, 1979), which would explain the aggressions as a result of the development of an insecure or ambivalent attachment. Although these issues have only been the subject of limited study, some authors (Laible et al., 2004; Unnever, 2005) have suggested that: a) the bullies' families may exhibit a high degree of both conflict and exposure to violence, which favor the development of an avoidant attachment, b) the victims' families may have an over-protective rearing style and exert great personal control, while c) the active victims refer to inconsistent parenting styles, and punitive, hostile or abusive treatment, leading to the development of an anxious and insecure attachment. In a more recent study, Arseneault, Bowes, and Shakoor (2010) found evidence that does not support these conclusions, and suggest their influence may not be the same in all situations. However, it has been observed that the parent-child relationship and the children's involvement in the dynamics of bullying may influence each other over time (Georgiu and Fanti, 2010).

Group processes: The peers

Saying that bullying is a group phenomenon implies that its motives are regarded as social rather than individual, that the victim and the bully are not the only ones involved in the phenomenon, that group norms influence the process, and that harassment probably serves to organize the socio-affective group and the implicit power hierarchies (Rigby, 2004; Salmivalli, 2010). The processes that underlie these dynamics are group-referred and belong to the field of social psychology.

Two theories explain the function of bullying within and for the group: the social identity theory -SIT-(Tajfel, 1984), and the social dominance (Sidanius, 1993) or resource control theory (Hawley, 1999). Both consider the reactive and, especially, the proactive aggression as an expression of a system of social values, and motivated by gaining social recognition and a powerful position within the peer group (Hawley, 2003; Salmivalli, Ojanen, Hampaa, & Pets, 2005). Both may explain the imbalance of power that seems to spontaneously occur among peers and the existence of socially prestigious bullies -because they successfully combine aggressive and prosocial behavior- (Salmivalli, 2010; Vaillancourt, Hymel, & McDougall, 2007). Furthermore, they explain the increase in aggressions during the periods in which the hierarchy is uncertain, for example, the beginning of the course, after the holidays, or the transition to another educational level, among others (Olthof et al., 2011; Pellegrini & Long, 2002; Powell, Brisson, Bender, Jenson, & Forrest-Bank, 2011).

According to the SIT foundation, the aggressions are part of a multifaceted process of social control (Farmer & Xie, 2007). The members of a group are provided with a social identity, which may be positive or negative if compared with other groups, and not only describes, but prescribes, which forms of behavior are appropriate for them (Ojala &Nesdale, 2004; Salmivalli, 2010). Group norms determine how, in which situations and against whom aggressions are allowed. Specifically, it was found that bullies would be motivated to commit aggressive acts either to safeguard their social standing if they belong to a popular group, or to positively distinguish themselves from another rejected group (Jones, Haslam, York, & Ryan, 2008; Nesdale, Milliner, Duffy, & Griffiths, 2009; Ojala & Nesdale, 2004; Olthof & Gossens, 2008). It is only when the social hierarchy is uncertain that those who have neither a high nor a low standing in the social hierarchy, but only an average one, can become aggressive, and the aggressions become more frequent and widespread (Farmer & Xie, 2007; Pellegrini & Long, 2002).

The peer group has an even greater influence on bullying than where other types of antisocial behavior are concerned (Espelage, Holt, & Henkel, 2003). The dynamics of the social roles can affect personal characteristics, such as self-concept, not only defining it depending on the group membership, but also by altering the expectations generated by a positive self-concept in the context of a positive or negative reputation among peers (Salmivalli et al., 2005). Likewise, popularity and social adjustment may occur together with aggression, increasing school disengagement trajectories (Troop-Gordon, Visconti, & Kuntz, 2011). From the foundation of SIT applied to harassment, the existence of clusters of adolescents with a similar level of aggression (Farmer & Xie, 2007; Jones et al., 2008), or with a similar level of prosocial behavior is also inferred (Salmivalli, 2010). Thus, friends can help protect each other from harassment when friendships arise from motives of affiliation and encourage empathy (Laible et al., 2004), or they can function as risk factors when they are aggressors or victims (Güroglu, van Lieshout, Haselager, & Scholte, 2007; Lam and Liu, 2007).

From an evolutionary perspective, the social dominance theory (Sidanius, 1993) explains prejudice and aggression resulting from a natural human predisposition to create hierarchies, whose function is not to provide the individual with a recognizable social identity, but to minimize social conflicts. In this context, harassment is considered as a strategy to gain mastery and control of social resources (Hawley, 1999, 2003), so the need to have a better social standing motivates aggressive behavior (Buelga, Cava, & Musitu, 2011; Powell et al., 2011). However, these variables seem to relate more to male harassment than female (Postigo et al., 2009). This theoretical perspective suggests that the bully is just a social control agent, and bullying minimizes social conflicts by focusing them on one or more individuals. As far as this is concerned, it has been observed that the fewer the victims in the group, the lower the level of overall aggressions, and the group (including the bystanders) tends to place greater blame on the victims for their own situation (Salmivalli, 2010) .

Although the group as a whole does not directly attack the victims, it is usually involved as it neither defends them nor rejects the bully (Rigby, 2004). Likewise, there are group factors that promote the "persecution" of difference, such as group cohesion, a high degree of hierarchy, and a rigid socio-affective structure (Carrera et al., 2011; Güroglu et al., 2007; Olthof & Gossens, 2008). The social roles involved in bullying can be described in a two-dimensional continuum: bullying attitude (positive, negative, neutral or indifferent) and behavior (involved or not involved) (Olweus, 2001).

Besides those of the bully and the victim, the most commonly studied roles are the assistants and followers of the bully, the victim defenders, and the uninvolved (Salmivalli, 2010). However, what makes the witnesses assume each role? The roles of bully and victim appear to depend more on individual and macro-contextual factors (Lee, 2011), while the behavior of witnesses seems to be mainly determined by the interaction between individual and group factors. Thus, in her recent review of bullying as a group phenomenon, Salmivalli (2010) notes that bystanders may decide not to intervene guided by group processes of behavioral inhibition, known as "diffusion of responsibility" and "pluralistic ignorance", which explains the behavioral dimension of the continuum, while the attitude dimension is explained by developmental and socio-cognitive processes, which are related to cognitive empathy and the theory of mind, among other personal characteristics. However, given the influence of both meso and macro-systems on the attitudes to violence, they should also be considered.

Meso and macro-system of bullying

The meso-system includes all the individual immediate contexts and the interactions between them (Figure 2). It is the least commonly studied level in peer harassment, with the exception of some school system variables, whose influence is explained by restorative processes (Table 4). Although there are no studies into the impact of the relationship between parents and teachers, it might be included here.

The macro-system includes the socio-cultural context in which individuals and groups develop (Figure 2). Along with individual differences, it seems to be the most influential factor in bullying and victimization (Lee, 2011). From this level, bullying is explained as a developmental learning process, which describes the effects of mass media (television, video games, Internet), or a group process, described by the SIT (Tajfel, 1984). The causes of bullying lie beyond the school, the family or even the teen culture itself. They could be located in the wider society and the historical socio-cultural differences between groups and their identities, as they are defined by religion, ethnicity, social classes and the sex/gender system, among others. Both types of processes are linked and operate through the generation and transmission of social attitudes that validate aggressions and harassment as a form of social interaction.

Restorative Processes: The School System

The school may encourage risky situations when it gives priority to competitiveness and academic success over individual concerns, and discipline is punitive and inconsistently applied, because the students try to compensate for the negative school climate they perceive, displaying behavior against the system -for example, assaulting others- (Cerezo & Ato, 2010; Gendron et al., 2011; Stassen, 2007). The influence of such factors on bullying has been explained by the theory of defiance (Sherman, 1993). This theory places the causes of violence in the perception of a basic injustice in the school code rules that motivates some children and adolescents to challenge them. It clearly highlights the influence of structural symbolic violence which is implicit in the social order, and in the school system, on individual aggressive behavior, as observed by Ttofi & Farrington (2008).

Reviewing previous correlational studies, Card and Hodges (2008) provide indirect evidence to this theory and conclude that both harassment and victimization are related to low levels of school adjustment. However, bullying behavior is related to a lack of confidence in the school system itself (Cunningham, 2007; Martinez-Ferrer, Murgui, Musitu, & Monreal, 2008), while victimization is only associated to academic failure (Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010). Furthermore, it was found that the school climate interacts with individual characteristics, such as self-esteem. If both are positive, the aggressions decrease, whereas a high self-esteem in the context of a negative school climate may increase the incidence of bullying, especially in the case of active victims (Cook et al., 2010, Gendron et al., 2011; Lee, 2011).

Developmental Processes: Modeling of Violence in Mass Media

The influence of the mass media on bullying is explained by developmental processes of social learning (Bandura, 1973). There is evidence that the recreation and glorification of violence on television encourage indifference and desensitization, and generate hostile and aggressive attitudes that mediate the effect of exposure to violence and the establishment of bullying dynamics (Coyne & Archer, 2005; Kuntsche et al., 2006). According to these studies, the effects of exposure to violence differ according to the socio-cultural context, the amount of violence, and the time spent watching television. Violent video games seem to have the same effect, although it is not the violence itself, but the degree of competitiveness involved, which increases aggression in children and adolescents (Adachi & Willoughby, 2011). However, for exposure to violent models to have a learning effect, their behavior should also be associated with a reward, and this has not been empirically studied yet.

As to competitiveness, the differential influence of collectivist vs. individualistic societies has been studied, noticing that collectivist cultures are less likely than individualistic to promote harassment (Lee, 2011). Presumably this is related to competition strategies inherent to the latter, but no specific studies have been found to support this idea.

Group Processes: Social norms and attitudes about the use of violence

The influence of the hostile feelings and attitudes among different social groups on bullying is explained by the SIT (Tajfel, 1984). For example, it has been observed that immigrant adolescents may suffer more victimization than natives, whether or not the harassment is related to ethnicity (Ombudsman, 2007; Strohmeier, Spiel, & Gradinger, 2008). And it is not only a matter of prejudice, which would justify the aggression, but also depends on the bully's perception of personal power and social identity. When both are negative, they are more likely to experience anxiety and hostility towards immigrants (increasing the likelihood of an aggression), to a greater degree than what is experienced under the same circumstances towards natives (Azzam, Beaulie, & Bugental, 2007). The underlying rule seems to state that "it is permissible to attack the stranger or someone different from me if I feel my identity and/or my personal power is threatened ". This kind of process could be extended to students from other parts of the same country, another city, another school or even another classroom, but no specific studies in the context of bullying have been found. Furthermore, there is evidence that both the level of harassment and victimization of immigrant students differ depending on the socio-cultural context and their ethnic diversity (Vervoort, Scholte, & Overbeek, 2010), highlighting the need to contextualize the research into bullying, and to consider the linguistic differences as what they are, expressions of different cultures.

SIT can also explain other rules about the use of violence: those concerning the sex/gender system. The studies focusing on this area are based on the basic and obvious idea that our society is sexist and this matters, pointing out some critical observations for research: a) the treatment of sexual and homophobic harassment as a subtype of bullying, whenever it is treated, may be disguising and minimizing this behavior, b) the masculinization of the phenomenon neglects important analysis of the origins and consequences of female violence, c) those variables related to sex and gender that are under investigation, with very few exceptions, are biologically based, and d) addressing bullying from a single, reductionist and essentialist perspective, regardless of the identity issues (social, ethnic, and gender, among others), avoids questioning it in political terms, and criticizing the social order and the social use of violence (Brown, Chesney-Lind, & Stein, 2007; Carrera et al., 2011; Felix & McMahon, 2006; Postigo et al., 2009; Rigby, 2004).

When looking closely at the influence of the sex/gender system, sexism and the associated stereotypes, it has been observed that bullying usually occurs between members of the same sex and, when it crosses genders, it is generally from boys towards girls (Felix & McMahon, 2006; Pellegrini & Long, 2002; Rigby, 2004). The witnesses are more likely to intervene in an assault if the victim and the bully are of the same sex as them (Hawkins, Pepler, & Craig, 2001). There is a positive relationship between high scores in Masculinity and aggressive behavior in both sexes (Gini & Pozzoli, 2006, Young & Sweating, 2004). Cognitive development in preschool predicts aggressive or disruptive behavior in boys, while in girls it predicts prosocial behavior (Walker, 2005). In turn, prosocial behavior predicts a high self-esteem in girls, but not in boys (Laible et al., 2004); while a lack of empathy predicts aggression in boys, but not in girls (Gini et al., 2007). Furthermore, bullying behavior may be less adaptive for girls, since female bullies seem to suffer more, and to exhibit less personal maladjustment and group acceptance than male bullies (Postigo et al., 2009).

But perhaps the most interesting observation is that the different forms of bullying follow gender norms, which are known even by 7-year-old children (Giles & Heyman, 2005). This has been related with the socio-affective resource competition proposed by the social dominance theory (Hawley, 1999). In this sense, it has been observed that boys overtly bully other boys to be accepted by the most aggressive and popular ones, trying to demonstrate competence and be considered as masculine, and so ascend in the social hierarchy (Gini & Pozzoli, 2006; Olthof & Goosens, 2008). Sothey also avoid any behavior that could be considered feminine, and victimization due to deviations from the gender stereotype. Instead, girls tend to covertly attack other girls to be accepted by the boys in general, and to preserve their social appeal based on femininity, because the use of direct violence is considered unacceptable (Hess & Hagen, 2006; Olthof & Goosens, 2008). However, laboratory tests have shown that the preference of girls and women for the covert forms of aggression is not biological (Bjorkqvist, 2001), although it does seem to be favored by the fact that they exhibit a greater range of social skills than boys at the same age (Postigo et al., 2009). The most comprehensive explanation lies in the concept of differential socialization by gender, since teens know that deviations from sexual stereotypes, among others, make them more vulnerable to victimization (Arseneault et al., 2010; Carrera et al. 2011; Young & Sweating, 2004). In fact, sexual preferences disappear when, instead of behavior in public, the private disposition to aggression is assessed (Nesdale et al., 2009; Tam & Taki, 2007). This points to how the social context influences individual behavior and highlights the close relationship between harassment, the sex/gender system and the foundation of the SIT.

Bullying Process and its Consequences

One more issue may be added to the problems involved in the delimitation of the bullying phenomenon: the lack of any studies of the process from a time perspective that go beyond the use of longitudinal methodologies. In this sense, only generic descriptions of the stages of bullying (Leymann, 1996; Olweus, 1993), and a qualitative study from the bullies' point of view (Lam & Liu, 2007) were found from the literature review carried out for this paper. According to these studies, the bullying process is described below in four phases (Table 5).

Bullying requires a previous phase, a context in which its occurrence is possible, probable and even profitable. At this early stage, the social hierarchy of the group is not clearly established and the potential bully may explicitly reject violence (Farmer & Xie, 2007; Lam & Liu, 2007; Leymann, 1996). Harassment probably began with indiscriminate attacks, by means of which the bully assesses the individual reactions of potential victims, which may vary between assertiveness, avoidance, perplexity, submission or reactive aggression. These attacks usually begin after a critical incident, or are based on a salient feature of the victims (Carrera et al., 2011, Jones et al., 2008; Olweus, 1993), but what seems essential is to pervert the potential conflict in such a way that it cannot be solved (Leymann, 1996). Thus, those who are trapped in the conflict, responding to bullying with submission or anger, or those with the most fragile social support network, are more likely to become victims; while others will learn that it is better to bully than to be bullied (Lam & Liu, 2007; Newman et al., 2005).

Real harassment begins in the second phase, since the aggressions are focusing on one or more subjects (Lam & Liu, 2007; Olweus, 1993). With each aggression, the power asymmetry between the bully and the victim becomes stronger. If the victim seems to be an easy target for humiliation, this will come to justify harassment itself (Garcia, 1997; Lam & Liu, 2007), and the bully will feel "provoked" by the victim (Aviles & Monjas, 2005). In the third phase, the process is already established: both victim and bully have adopted their identity, and the group recognizes them as such (Jones et al., 2008; Lam & Liu, 2007). The stigmatization of the victim generates psychological damage that is not always visible, as it is usually in the fourth and final phase when the consequences of this demoralization process become clear and evident. The process ends when the victim leaves the school, the bully gives up violence or simply changes his/her victim (Lam & Liu, 2007; Leymann, 1996).

Furthermore, as proof of the complexity of bullying, some consequences of these dynamics seem to be causes as well. Specifically, reciprocal causal relationships between adjustment and self-concept problems and bullying behavior have been observed (Boulton et al., 2010); as have relationships between the typical internalization problems of the victims (anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts) and the victimization itself (Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010).

Discussion

Bullying is a subtype of circular violence, a phenomenon that feeds on itself and, as stated in the definition (e.g. see Vaillancourt et al., 2007), lies in the abuse of power. While this article focuses on recent studies (especially review and meta-analysis), chronologically, the study of peer harassment has been expanding the focus from the individual to the group and/or macro-contextual variables (although there are exceptions). The present work summarizes specific theories that have been applied to the comprehension of the phenomenon, ascending within this systemic order of inclusiveness, and taking into account the relationships between different ecological levels. These theories underlie the most consistent observations, so research can be guided by an integrative framework, which organizes the knowledge gained and explains the variability observed in different cultural contexts (Boulton et al., 2010; Gendron et al., 2011; Georgiu & Fanti, 2010; Lee, 2011).

This integrative perspective suggests that, at different levels, every specific theory is consistent and relevant to the understanding of peer victimization. Thus, all show a common element which is the essential characteristic of bullying: the establishment of hierarchical social relationships that, taken to extremes, end in a dominion/submission relationship (Farmer & Xie, 2007; Olweus, 2001). The aggressions (whether they are proactive or reactive, overt or covert) are a struggle dynamic for power, a way to obtain or regain control and an auspicious social identity (Hawley, 1999; Jones et al., 2008; Lam & Liu, 2007). Therefore, the only way to prevent bullying and treat its effects must be to empower the children and adolescents. That is, make an effort for them to be able to freely relate, feel, think, do and be, with guaranteed rights and duties.

The holistic approach to the use and abuse of personal power implies taking into account all the ecological levels. Thus, research will be able to assess the causal influences both quantitatively and qualitatively, and study their relationships. In this sense, many endeavors have been carried out, such as those studies focused on interaction between variables (e.g. Laible et al., 2004), the qualitative analysis of the teenagers' discourses on bullying (e.g. Lam & Liu, 2007), and the reviews and meta-analysis of quantitative variables (e.g. Card & Hodges, 2008; Cook et al., 2010). However, these studies have not yet been integrated within a broader bullying framework that enables specific theories to be used as links between different research and intervention areas.

To develop efficient interventions, some authors suggest the research must assume multi-causality, putting together all the pieces of the puzzle, and promote holistic and ecological approaches (Carrera et al., 2011; Salmivalli, 2010). Nevertheless, whatever the intervention format (e.g. individual or group), the core must be the concept of personal power. Thus, the development of specific interventions is required for targeted populations, whether they are defined by social role, age, gender and/or the immigrant experience, since power dynamics vary depending on these variables. Lastly, certain parameters of the bullying process that affect the power dynamics need to be defined, such as the phase and the predominant type of aggression, among others.

Specifically, as Burk et al. (2011) suggest, it would be useful to develop specific interventions for active victims, especially at an early age, since they can already be involved in bullying and continue for several years. It is also important not to forget the influence of the peer context, so that focusing on empowering witnesses may be faster, more useful and more effective than dealing with bullies, followers or their assistants (Salmivalli, 2010). Furthermore, there should always be emphasis on considering the influence of socio-cultural issues, the ethnic diversity of the group, and the sex/gender system, since all of them shape both the form and nature of the harassment, its causes and consequences (Postigo et al., 2009). As far as the latter is concerned, it would be useful to reverse the trend of bullying masculinization, dealing with sex and gender beyond the restriction of their study as simple dichotomous biological variables (Brown et al., 2007; Carrera et al., 2011; Rigby, 2004; Stassen, 2007). Finally, research has to focus on one of its major gaps, that is to identify which theory (and variable/s) is more relevant than another in every bullying process; so that may facilitate the development of effective interventions. Likewise, it will be useful to delve deeper into the role of mass media and technology, not only because of the influence they exert on the establishment of bullying dynamics and the opportunities they provide for exposure to violence and ways in which it can be used perversely, but especially due to the possibilities they afford for both raising awareness of bullying and reaching the adolescents.

Conclusions

This paper provides a relatively simple framework, both broad and flexible, within which all the theories, factors and actors involved in the bullying process may be included. Currently, a great deal is known about this area, and we are able to understand the process by which bullies and groups come to abuse and moral "perversion", which is the essence of harassment. We therefore believe that the integration of theories and findings may be useful for future research. This integrative approach may also be applied to the development of interventions. Although the ecological levels cannot be tackled all at once and do not all have the same relevance in all cases, they must be taken into account both in research and intervention. We believe that any intervention should be able to provide tools and strategies with which to reach individual awareness of personal power and to use it (through competition with oneself and not with another person) in the construction of an auspicious social identity. However, this effort requires changing the socio-cultural substrate that carries the emergence of the bullying phenomenon. Therefore, whatever the format or targeted population of the intervention, it is necessary to focus on two main aspects: the empowerment of individuals, and the raising of social consciousness concerning the use of personal power as a form of self-knowledge and recognition of others, regardless of their personal identity, ethnicity, gender or social status, among other things.

References

1. Abramson, L.Y., Seligman, M.E.P., & Teasdale, J. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F%2F0021-843X.87.1.49 [ Links ]

2. Adachi, P.J. C., & Willoughby, T. (2011). The effect of video game competition and violence on aggressive behavior: Which characteristic has the greatest influence? Psychology of Violence, 1(4), 259-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2Fa0024908 [ Links ]

3. Ahmed, E. (2006). Understanding bullying from a shame management perspective: Findings from a three-year follow-up study. Educational and Child Psychology, 23(2), 25-39. [ Links ]

4. Ahmed, E., & Braithwaite, V. (2006). Forgiveness, reconciliation, and shame: Three key variables in reducing school bullying. Journal of Social Issues, 62(2), 347-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1540-4560.2006.00454.x [ Links ]

5. Ahmed, E., Harris, N., Braithwaite, J., & Braithwaite, V. (2001). Shame Management through Reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

6. Aoyama, I. (2010). Cyberbullying: What are the psychological profiles of bullies, victims, and bully-victims? Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 71(10-A), 3526. [ Links ]

7. Archer, J., & Coyne, S.M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 212-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207%2Fs15327957pspr09032 [ Links ]

8. Arseneault, L., Bowes, L., & Shakoor, S. (2010). Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: 'Much ado about nothing'? Psychological Medicine, 40, 717-729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0033291709991383 [ Links ]

9. Avilés, J., & Monjas, I. (2005). Estudio de incidencia de la intimidación y el maltrato entre iguales en la educación secundaria obligatoria mediante el cuestionario CIMEI (Avilés, 1999) -Cuestionario sobre intimidación y maltrato entre iguales- (Study of incidence of intimidation and bullying in compulsory secondary education through the questionnaire CIMEI (Avilés, 1999)-Questionnaire on intimidation and bullying.) Anales de Psicología, 21(1), 27-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.21.L27091 [ Links ]

10. Azzam, T. I., Beaulieu, D. A., & Bugental, D. B. (2007). Anxiety and hostility to an outsider, as moderated by low perceived power. Emotion, 7, 660-667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F1528-3542.7.3.660 [ Links ]

11. Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning theory analysis. New York: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

12. Björkqvist, K. (2001). Social defeat as a stressor in humans. Physiology & Behavior, 73(3), 435-442. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0031-9384%2801%2900490-5 [ Links ]

13. Boulton, M.J., Smith, P.K., & Cowie, H. (2010). Short-term longitudinal relationships between children's peer victimization/bullying experiences and self-perceptions: Evidence for reciprocity. School Psychology International, 31(3), 296-311 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0143034310362329 [ Links ]

14. Bowlby, J. (1979). The Making and Breaking of Afectional Bonds. London: Tavistock. [ Links ]

15. Bronfenbrenner, U. (1987). La Ecología del Desarrollo Humano (The Ecology of Human Development). Madrid: Paidós. [ Links ]

16. Brown, L.M., Chesney-Lind, M., & Stein, N. (2007). Patriarchy matters. Toward a gendered theory of teen violence and victimization. Violence Against Women, 13(12), 1249-1273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077801207310430 [ Links ]

17. Buelga, S., Cava, M., & Musitu, G. (2011). Reputación social, ajuste psicosocial y victimización entre adolescentes en el contexto escolar (Social reputation, psychosocial adjustment and victimization among adolescents in the School). Anales de Psicología, 28(1), 180-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.28.L140652 [ Links ]

18. Burk, L.R., Armstrong, J.M., Park, J.H., Zahn-Waxler, C., Klein, M.H., & Essex, M.J. (2011). Stability of early identified aggressive victim status in elementary school and associations with later mental health problems and functional impairments. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(2), 225-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10802-010-9454-6 [ Links ]

19. Calvete, E., & Orue, I. (2010). Cognitive schemas and aggressive behavior in adolescents: The mediating role of social information processing. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(1), 189-200. [ Links ]

20. Card, N. A., & Hodges, E. V. E. (2008). Peer victimization among schoolchildren: Correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 451-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2Fa0012769 [ Links ]

21. Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., & Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79(5), 1185-1229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x [ Links ]

22. Carrera, M.V., DePalma, R., & Lameiras, M. (2011). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of bullying in School settings. Educational Pscyhology Review, 23, 479-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9171-x [ Links ]

23. Cerezo, F., & Ato, M. (2010). Estatus social, género, clima del aula y bullying entre estudiantes adolescentes (Social status, gender, classroom climate and bullying among teenage students). Anales de Psicología, 26(1), 137-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.26.1.92131 [ Links ]

24. Coyne, S.M., & Archer, J. (2005). The relationship between indirect aggression and physical aggression on television and in real life. Social Development, 14(2), 324-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-9507.2005.00304.x [ Links ]

25. Cook, C.R., Williams, K.R., Guerra, N.G., Kim, T.E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimizations in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020149 [ Links ]

26. Crick, N.R., & Dodge, K.A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social-information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 11, 74-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74 [ Links ]

27. Cunningham, N.J. (2007). Level of bonding and perception of the school environment by bullies, victims, and bully-victims. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(4), 457-478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0272431607302940 [ Links ]

28. Dollard, J., Doob, C.W., Miller, N.E., Mowrer, O.H., & Sears, R.R. (1939). Frustration and Aggression. New Haven: Yale University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F10022-000 [ Links ]

29. Estévez, E., Martínez, B., & Musitu, G. (2006). Self-esteem in adolescent offenders and victims in school: A multidimensional perspective. Psychosocial Intervention, 15(2), 223-233. [ Links ]

30. Espelage, D.L., Holt, M.K., & Henkel, R.R. (2003). Examination of peer-group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Development, 74(1), 205-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2F146 78624.00531 [ Links ]

31. Farmer, T.W., & Xie, H. (2007). Aggression and school social dynamics: The good, the bad, and the ordinary. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 461-478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jsp.2007.06.008 [ Links ]

32. Felix, E.D., & McMahon, S.D. (2006). Gender and multiple forms of peer victimization: How do they influence adolescent psychosocial adjustment? Violence and Victims, 21 (6), 707-725. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891%2Fvv-v21i6a003 [ Links ]

33. Garaigordobil, M. (2011). Prevalencia y consecuencias del cyberbullying: Una revisión (Prevalence and consequences of cyberbullying: A review). International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 11(2), 233-254. [ Links ]

34. García, J. (1997). Un modelo cognitivo de las interacciones matón-víctima (A cognitive model of bully-victim interactions). Anales de Psicología, 13(1), 51-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.13.1.30711 [ Links ]

35. Gendron, B.P, Williams, K.R., & Guerra, N.G. (2011). Analysis of bullying among students within schools: Estimating the effects of individual normative beliefs, self-esteem, and school climate. Journal of School Violence, 10(2), 150-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010.539166 [ Links ]

36. Georgiou, S.N., & Fanti, K.A. (2010). A transactional model of bullying and victimization. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 13(3), 295-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11218-010-9116-0 [ Links ]

37. Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2006). The role of masculinity in children's bullying. Sex Roles, 54, 585-588. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9015-1 [ Links ]

38. Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2007). Does empathy predict adolescents' bullying and defending behavior? Aggressive Behavior, 33, 467-476. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.20204 [ Links ]

39. Giles, J.W., & Heyman, G.D. (2005). Young children's beliefs about the relationship between gender and aggressive behaviour. Child Development, 76(1), 107-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-8624.2005.00833.x [ Links ]

40. Güroglu, B., van Lieshout, C.F.M., Haselager, G.J.T., & Scholte, R.H.J. (2007). Similarity and complementary of behavioral profiles of friendship types and types of friends: Friendships and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(2), 357-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00526.x [ Links ]

41. Hawkins, D.L.; Pepler, D.J., & Craig, W.M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development; 10(4), 512-527. [ Links ]

42. Hess, N.H., & Hagen, E.H. (2006). Sex differences in indirect aggression. Psychological evidence from young adults. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 27, 234-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.11.001 [ Links ]

43. Hawley, P.H. (1999). The ontogenesis of social dominance: A strategy-based evolutionary perspective. Developmental Review, 19, 97-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/drev.1998.0470 [ Links ]

44. Hawley, P.H. (2003). Strategies of control, aggression and morality in preschoolers: an evolutionary perspective. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 85(3), 213-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0965(03)00073-0 [ Links ]

45. Jones, S.E., Haslam, S.A., York, L., & Ryan, M.K. (2008). Rotten apple or rotten barrel? Social identity theory and children's responses to bullying. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26(1), 117-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/026151007X200385 [ Links ]

46. Kunstche, E., Pickett, W., Overpeck, M., Craig, W., Boyce, W., & de Matos, M.G. (2006). Television viewing and forms of bullying among adolescents from eight countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(6), 908-915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.007 [ Links ]

47. Laible, D.J., Carlo, G., & Roesch, S.C. (2004). Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy and social behaviours. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 703-716. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.adolescence.2004.05.005 [ Links ]

48. Lam, D.B. & Liu, A.W.H. (2007). The path through bullying -A process model from the inside story of bullies in Hong Kong secondary schools. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(1), 53-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10560-006-0058-5 [ Links ]

49. Law, D.M., Shapka, J.D., Hymel, S., Olson, B.F., & Waterhouse, T. (2012). The changing face of bullying: An empirical comparison between traditional and internet bullying and victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 226-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.004 [ Links ]

50. Lee, C.H. (2011). An ecological systems approach to bullying behaviors among middle school students in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(8), 1664-1693. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260510370591 [ Links ]

51. Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 165-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414853 [ Links ]

52. Martinez-Ferrer, B., Murgui, S., Musitu, G., & Monreal, M.C. (2008). The role of parental support, attitudes toward school, and school self-esteem in adolescents. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 8(3), 679-692. [ Links ]

53. Merrell, R., Buchanan, R., & Tran, O.K. (2006). Relational aggression in children and adolescents: A review with implications for school settings. Psychology in the Schools, 43(3), 345-360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fpits.20145 [ Links ]

54. Morrison, B. (2006). School bullying and restorative justice: Toward a theoretical understanding of the role of respect, pride, and shame. Journal of Social Issues, 62(2), 371-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1540-4560.2006.00455.x [ Links ]

55. Nakamoto, J., & Schwartz, D. (2010). Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development, 19(2), 221-242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00539.x [ Links ]

56. Nansel, T., Craig, W., Overpeck, M., Saluja, G., Ruan, W., & the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Bullying Analyses Working Group (2004). Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 158, 730-736. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Farchpedi.158.8.730 [ Links ]

57. Nesdale, D., Milliner, E., Duffy, A., & Griffiths, J.A. (2009). Group membership, group norms, empathy, and young children's intentions to aggress. Aggressive Behavior, 35(3), 244-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.20303 [ Links ]

58. Newman, M.L., Holden, G.W., & Delville, Y. (2005). Isolation and the stress of being bullied. Journal of Adolescence, 2, 343-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.08.002 [ Links ]

59. Ojala, K., & Nesdale, D. (2004). Bullying and social identity: The effects of group norms and distinctiveness threat on attitudes towards bullying. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 22, 19-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348%2F026151004772901096 [ Links ]

60. Olthof, T., & Gossens, F.A. (2008). Bullying and the need to belong: Early adolescents' bullying-related behaviour and the acceptance they desire and receive from particular classmates. Social Development, 17(1), 24-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-9507.2007.00413.x [ Links ]

61. Olthof, T., Goossens, F.A., Vermande, M.M., Aleva, E.A., & van der Meulen, M. (2011). Bullying as strategic behavior: Relations with desired and acquired dominance in the peer group. Journal of School Psychology, 49(3), 339-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.03.003 [ Links ]

62. Olweus, D. (1993). Conductas de acoso y amenaza entre escolares (Bullying: What We do and What We Know). Madrid: Morata. [ Links ]

63. Olweus, D. (2001). Peer harassment: A critical analysis and some important issues. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized (pp. 3-20). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

64. Ombudsman (2007). School Violence: Bullying in Secondary Education 2000-2006. Madrid: Ministry of Education and Culture. [ Links ]

65. Ortega, R., Sánchez, V., & Menesini, E. (2002). Violencia entre iguales y desconexión moral: Un estudio transcultural (Peer violence and moral disengagement: A cross-cultural study). Psicothema, 14(Supl.), 37-49. [ Links ]

66. Pellegrini, A.D., & Long, J.D. (2002). A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20(2), 259-280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348%2F026151002166442 [ Links ]

67. Postigo, S., González, R., Mateu, C., Ferrero, J., & Martorell, C. (2009). Diferencias conductuales según género en convivencia escolar (Behavioral differences by gender in school life). Psicothema, 21(3), 453-458. [ Links ]

68. Powell, A., Brisson, D., Bender, K.A., Jenson, J.M., & Forrest-Bank, S. (2011). Patterns of aggressive behavior and peer victimization from childhood to early adolescence: A latent class analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(6), 644-655. [ Links ]

69. Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1, 515-526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00076512 [ Links ]

70. Reijntjes, A. K., Kamphuis, J.H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect: The International Journal, 34(4), 244-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009 [ Links ]

71. Rigby, K. (2004). Addressing bullying in schools. Theoretical perspectives and their implications. School Psychology International, 25(3), 287-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0143034304046902 [ Links ]

72. Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 112-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.avb.2009.08.007 [ Links ]

73. Salmivalli, C., Ojanen, T., Haampaa, J., & Peets, K. (2005). "I'm OK but you're not" and other peer-relational schemas: explaining individual differences in children's social goals. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 363-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.412.363 [ Links ]

74. Sameroff, A. J. (1987). The social context of development. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Contemporary Topics in Developmental Psychology (pp. 273-29). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

75. Sánchez, V., Ortega, R., & Menesini, E. (2012). La competencia emocional de agresores y víctimas de bullying (Emotional competence of aggressors and victims of bullying). Anales de Psicología, 28(1), 71-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.28.1.140542 [ Links ]

76. Sherman, L. (1993). Defiance, deterrence, and irrelevance: A theory of the criminal sanction. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 30, 445-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0022427893030004006 [ Links ]

77. Sidanius, J. (1993). The psychology of group conflict and the dynamics of oppression: A social dominance perspective. In W. McGuire & S. Iyengar (Eds.), Current Approaches to Political Psychology (pp. 183-219). Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

78. Stassen, K. (2007). Update on bullying at school: science forgotten? Developmental Review, 27, 90-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2006.08.002 [ Links ]

79. Stavrinides, P., Georgiu, S., & Theofanus, V. (2010). Bullying and empathy: A short-term longitudinal investigation. Educational Psychology, 30(7), 793-802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F01443410.2010.506004 [ Links ]

80. Strohmeier, D., Spiel, C., & Gradinger, P. (2008). Social relationships in multicultural schools: Bullying and victimization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5, 262-285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17405620701556664 [ Links ]

81. Tajfel, H. (1984). Grupos Humanosy Categorías Sociales (Human Groups and Social Categories). Barcelona: Herder. [ Links ]

82. Tam, F. W., & Taki, M. (2007). Bullying among girls in Japan and Hong Kong: An examination of the frustration-aggression model. Educational Research and Evaluation, 13, 373-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13803610701702894 [ Links ]

83. Tokunaga, R.S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 277-287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014 [ Links ]

84. Troop-Gordon, W., Visconti, K.J., & Kuntz, K.J. (2011). Perceived popularity during early adolescence: Links to declining school adjustment among aggressive youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 31(1), 125-151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0272431610384488 [ Links ]

85. Ttofi, M.M., & Farrington, D.P. (2008). Bullying: Short-term and long-term effects, and the importance of defiance theory in explanation and prevention. Victims & Offenders, 3(2-3), 289-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15564880802143397 [ Links ]

86. Unnever, J.D. (2005). Bullies, aggressive victims and victims: Are they distinct groups? Aggressive Behavior, 31, 153-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.20083 [ Links ]

87. Vaillancourt, T., Hymel, S., & McDougall, P. (2007). Bullying is power: Implications for school-based intervention strategies. In J.E. Zins, M.J. Elias & C.A Maher (Eds.), Bullying, Victimization, and Peer Harassment: A Handbook of Prevention and Intervention (pp. 317-338). Nueva York: Haworth Press. [ Links ]

88. Vervoort, M.H.M., Scholte, R.H.J., & Overbeek, G. (2010). Bullying and victimization among adolescents: The role of ethnicity and ethnic composition of school class. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10964-008-9355-y [ Links ]

89. Walker, S. (2005). Gender differences in the relationship between young children's peer-related social competence and individual differences in theory of mind. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 166(3), 297-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200%2FGNTP.166.3.297-312 [ Links ]

90. Young, R., & Sweating, H. (2004). Adolescent bullying, relationships, psychological well-being and gender-atypical behaviour: a gender diagnostic approach. Sex Roles, 50(7), 525-537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FB%3ASERS.0000023072.53886.86 [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Remedios González

University of Valencia

School of Psychology

Department of Personality, Evaluation and Psychological Treatments

Av. Blasco Ibáñez, 21

46010 Valencia (Spain)

E-mail: gonzalrb@uv.es

Artículo recibido: 5-3-2012

revisado: 20-7-2012

aceptado: 30-7-2012