My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Anales de Psicología

On-line version ISSN 1695-2294Print version ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.31 n.1 Murcia Jan. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.1.166591

Supporting people with Autism Spectrum Disorders in leisure time: Impact of an University Volunteer Program, and related factors

Apoyos en ocio para personas con Trastorno de Espectro Autista: Impacto de un Programa de Voluntariado y factores relacionados

Carmen Nieto1, Eva Murillo2, Mercedes Belinchón1, Almudena Giménez3, David Saldaña4, Ma-Angeles Martínez5 y María Frontera6

1Departamento de Psicología Básica, Facultad de Psicología (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) (Spain)

2Departamento Interfacultativo de Psicología Evolutiva y de la Educación (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) (Spain)

3Departamento de Psicología Básica, Facultad de Psicología (Universidad de Málaga) (Spain)

4Departamento de Psicología Evolutiva y de la Educación, Facultad de Psicología (Universidad de Sevilla) (Spain)

5Departamento de Ciencias de la Educación, Facultad de Educación (Universidad de Burgos) (Spain)

6Departamento de Psicología y Sociología, Facultad de Educación (Universidad de Zaragoza) (Spain)

ABSTRACT

Social participation has positive effects on mental and physical health, and it can be taken as an indicator of quality of life. However, the participation of people with disabilities in their communities is still scarce, especially for people with autism.

The impact on individual satisfaction produced by a university volunteer program (APUNTATE) aimed at supporting people with autism in leisure activities was evaluated. A questionnaire of impact assessment, that identifies those areas where the impact is greater, was completed by 159 families of users and 230 volunteers.

Users and volunteers reported a very high level of satisfaction with the program, but personal characteristics of users slightly influenced the scores. The structured organization of the program, and the continued training and support received by volunteers were the highest valued aspects. The adaptation of supports to the individual needs of users and volunteers was another relevant factor to explain the results.

The evaluation obtained shows that volunteering programs to promote the participation of people with ASD can be successfully implemented in public universities. These programs can increase the personal development, facilitate a change of attitude towards people with disabilities and can improve future employment prospects of students.

Key words: Autism; volunteering; recreation and leisure; program evaluation.

RESUMEN

La participación social tiene efectos positivos en salud mental y física, y puede tomarse como un indicador de calidad de vida. Sin embargo, la participación de personas con discapacidad en su comunidad es aún escasa, especialmente para las personas con autismo. En este trabajo evaluamos el grado de satisfacción con un programa de voluntariado universitario dirigido a personas con autismo para apoyar actividades de ocio y tiempo libre (APUNTATE).

Un total de 159 familias de usuarios y 230 voluntarios cumplimentaron un cuestionario de satisfacción que identificó las áreas en las que el programa tenía más impacto. Los resultados mostraron una alta satisfacción general tanto en usuarios como en voluntarios, aunque algunas características personales de los usuarios generaron leves diferencias. Los aspectos más valorados fueron la organización del programa, la formación y tutorización continua que se ofrecía a los voluntarios. Otra característica del programa, ampliamente valorada, fue la capacidad de éste de adaptar los apoyos a las necesidades individuales de usuarios y voluntarios.

Este trabajo pone de manifiesto que la universidad pública puede implementar con éxito programas de apoyos para promover la participación social. Estos programas pueden favorecen el desarrollo personal, favorecer el cambio de actitudes hacia las personas con discapacidad y mejorar las perspectivas de empleo de los estudiantes.

Palabras clave: Autismo; voluntariado; ocio y tiempo libre; evaluación de programas.

Introduction

Participating in social activities and contexts is crucial for social and personal development. Being involved in formal and informal activities with other people provides opportunities to interact, to develop skills and to make new friends. It also provides meaning and purpose to life (Law & King 2000). Several studies show that participating in daily-life social activities, recreation and leisure has positive effects on physical and mental health (Kolehmainen et al., 2011; González & Extrema, 2010; Hilton, Crouch & Israel, 2008; Law & King, 2000; Tinsley & Eldredge, 1995). Consequently, the level of involvement in these activities has been considered an indicator of quality of life as well as a social right (Schalock, 1996).

People with disabilities have few chances of accessing community environments and participating in social activities, which put them at risk of social exclusion (Cowart, Saylor, Dingle & Mainor, 2004; Hilton et al., 2008). When they take part in a social activity, their interaction is mostly limited to a physical contact and can rarely be considered a true social interaction (Hughes et al., 2002; Solish, Perry & Minnes, 2010). Children with a disability tend to be more passive and to spend more time playing at home than their typically developing peers (Geisthardt, Brotherson & Cook, 2002). They are also more prone to practice activities alone (Buttimer & Tierney, 2005; Orsmond, Krauss & Seltzar, 2004). Their lack of social involvement extends to adolescence and to the adulthood, worsening with age (Newton & Honer, 1993; Orsmond et al., 2004). Adolescents and adults with disabilities go less frequently to cinema or shopping, spend less time visiting their friends at home, and, in general, are much less involved in their communities (Kampert & Goreczny, 2007).

This reduced social participation seems to be the result of personal and environmental factors. With regard to the first ones, Law et al. (2004) studied 427 children with different physical disabilities and a broad range of adaptive abilities, concluding that the level of participation was linked to age, functional and communication abilities, autonomy, and motor skills. Other studies also show that people with autism spectrum disorders (hereinafter, ASD) are more socially impaired than people with other disabilities and conditions (Houchhaser & Engel-Yeger, 2010; Solish et al., 2010).

Hilton et al. (2008) found that people with ASD participate in formal social activities, although they are scarcely involved in informal (leisure and physical) activities. Furthermore, as they grow older, the number of social activities becomes reduced. Such argument is consistent with the findings of Orsmond et al. (2004) in a sample of adolescents and adults with ASD. In this study, 46% of the participants failed to report any relation with peers in either structured or informal social contexts.

With regard to contextual factors, income has been pointed out as one of the factors that most seriously restricts social participation of people with disabilities (Law et al., 2004). Attitudes have also been identified as important barriers to participation in leisure activities (e.g. Fichten, Schipper & Cutler, 2005; Perry, Ivy, Conner & Shelar, 2008; Phoenix, Miller & Schleien, 2002). However, interacting with people with disabilities contributes to change attitudes. Thus, Fichten et al. (2005) found that a continued contact between students with and without disabilities within a volunteer program reduced discomfort and it improved non-disabled volunteers' self-concept. "Keeping in touch" reduced their social distance and increased the probability that people with disabilities were involved in future interactions.

According to the former results, recent studies have emphasized the need to develop programs especially designed to provide disabled people with more opportunities of social participation (García-Villamisar & Dattilo, 2010). However, and specifically in the case of people with autism, volunteer programs only seem to reduce the negative influence of contextual factors on social participation when they fulfill two conditions (Fitchen et al., 2005): (1) they provide a continued period of contact, and (2) the person with autism is prepared to anticipate possible difficulties. These programs also represent an opportunity for people with low income to access to some specific contexts and activities. However, at present, in many countries such as Spain, the offer of this kind of services is still scarce (Belinchón, 2001; Belinchón, Hernández & Sotillo, 2008).

Over the last years, it has been observed an increase of volunteer programs, particularly of volunteer programs that encourage social participation of people with disabilities. A closer examination of the effects of these programs reveals that not only they benefit the users of the service, but also the volunteers and the extended community get some benefits. Post & Neimark (2007), for example, reported that the participation in a volunteer program had a positive impact on happiness, mood, self-esteem, social skills and contacts, and mental health. Yates (1995) (cited in Phoenix, Miller & Schleien, 2002) concluded that volunteering in the youth helps to establish a social connection with other people, to develop a moral and political consciousness, and to perceive that every person can influence the society. Volunteering also develops social and personal responsibility (Moore & Allen, 1996). Similarly, Phoenix et al. (2002) referred to the adoption of a philosophy of inclusion as a consequence of volunteering.

Many of these programs offer relatively unstructured or unstable services, and the evaluation of their effects and quality of service is scarce or non-existent. (i.e. Wardell, Lishman & Whalley, 2000). There are nevertheless some highly structured and regulated programs where volunteer recruitment, training, support and evaluation are carefully carried out. Those programs may consume a greater amount of resources, particularly during the initiation and training periods. However, their volunteers show an intrinsic motivation, since they expect to acquire new abilities, and they are more prone to commitment. This seems to indicate that the quality of the voluntary work is far more effective when it is structured and well organized, although it inevitably entails greater costs for the organization.

Universities can provide potentially ideal settings to organize structured, low cost and efficient volunteering programs, inasmuch as (a) universities receive every year groups of young people with high motivation for training, (b) universities are primarily aimed to teaching and research, although they also aspire to promote social change, (c) students rotation or continued evaluation are not considered as disadvantages, since both are inherent to the standard functioning of universities, and, (d) universities can develop integrated programs of training, research, and social action.

In this study we will analyze the perceived impact1 and satisfaction of participants with the Program for University Supports for people with Autism Spectrum Disorders (APUNTATE, in its Spanish acronym). It is our aim to illustrate how a satisfactory volunteering program to support leisure activities for people with ASD can be implemented in public universities. We will compare the perceived impact of this program by users taking into account some personal and contextual variables that could influence on social participation. We considered that a support may be adequate when it is personcentered, that is: it is individualized, ecological and based on personal choices and preferences.

APUNTATE provided individualized support for people with ASD of different ages during their leisure time, in their usual environments. The program was initiated at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid in 2001, being later offered in other four Spanish public universities (Zaragoza, Sevilla, Burgos and Málaga)2 until 2011.

Up to now, a total of 1202 people with ASD and 1416 university students have participated in APUNTATE. Briefly described, the program runs through five stages in each academic year: (1) publicity of the program amongst universities and families, (2) selection and recruitment of families and volunteers, (3) volunteer training, (4) provision of individualized supports, and (5) program evaluation by all the participants (users with ASD, families, volunteers, and managers of the program). Each volunteer was assigned to a person with ASD and provides to him/her four hours per week of support during leisure. The activities volunteers and users with ASD did together were based on the users' preferences and choices and were developed in the community. Volunteers received, in addition to initial training, individualized support along the program by a counselor (called "mentor") with larger experience in the field.

All actions planned for each phase of the program were highly structured and supervised, in order to ensure coordination amongst the five participating universities. At the end of year, volunteers received an academic accreditation for the training received.

In this study we analyze the perceived impact and satisfaction of participant families and volunteers with the program APUNTATE, as well as the relationship between these measures and some personal and contextual factors. Data for this study were collected during the academic year 2009/2010.

As a general hypothesis, we maintain that providing an adequate support for leisure to people with ASD may have a global positive impact regardless personal factors like age, communicative abilities or behavioral flexibility. However, differences attributable to some personal and/or contextual factors may be obtained if impact is assessed more in depth.

Method

Participants

All participants (185 families, 290 volunteers) were informed about the research project and invited to participate. Only data from those participants who agreed to be involved were considered.

Participant families. Families of 159 individuals with a diagnosis of ASD aged 3 to 43 (M = 11.98, SD = 8.59) answered the questionnaire. Male to female ratio was 4.3:1, and 48% participated in the program for the first time.

In order to facilitate data analysis, the sample was first divided into three age groups (3 to 7, 8 to 12, and over 12 years), and then classified into three variables considered as relevant to social participation in previous studies: participants' communicative abilities, level of flexibility, and the recreational resources available in their communities2 (see Table 1).

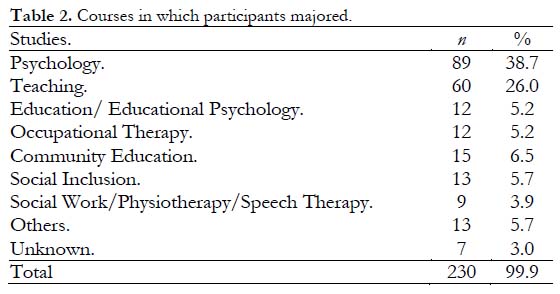

Volunteers. 230 university or higher-education students answered the questionnaire, being 205 (89%) females and 25 males. Their distribution by degrees is presented in Table 2.

Demographic details were also collected, including gender and their main motivations to participate.

Instruments

Two questionnaires/ (families and volunteers) were elaborated for this study based on the Volunteering Impact Assessment Toolkit (Institute for Volunteering Research, 2004). This questionnaire was originally designed to measure the impact of programs in five domains or Capitals (Physical, Economic, Human, Social and Cultural), as well as to assess both their expected and unexpected effects.

In our study, only four capitals were assessed: Physical Capital refers to effects on health or wellness; Economic Capital describes the financial and economic profits obtained from participating in the program; Human Capital relates to the acquisition of skills and personal development; finally, Social Capital refers to creating a more cohesive community, and helping to increase mutual understanding. Although not originally designed for people with ASD, the Volunteering Impact Assessment Toolkit yields a componential vision of the effects, or henceforth "impact", which seemed to us especially suitable to the aims of this study, since social participation can affect to a variety of dimensions of the quality of life (emotional, well-being, interpersonal relations, etc.) (see Schalock, 1996). In addition, the questionnaire fits the great heterogeneity of participants in our program (users with ASD of different ages, levels of ability, difficulties and resources, as well as volunteers of different ages, degrees, universities, and geographical regions).

Questionnaire for Families. The APUNTATE Impact Questionnaire for Families of People with ASD has two sections. The first one anonymously collects personal information (gender, age, communication abilities and behavioral flexibility), as well as data of a contextual factor (recreational resources in the community). The second section includes 38 items (see Table 3): Physical Capital, 12 items, (e.g. 'level of satisfaction with amount of support"), Economic Capital, 3 items, (e.g. "this volunteering has supported direct or indirectly your family economy"); Human Capital, 12 items, (e.g. "capacity of users to express preferences and choices"); and Social Capital, 11 items, (e.g. "opportunities for your child to relate to other people"). Each item was scored within a five-point Likert scale, according to the degree of satisfaction or change perceived, ranging from 1 as "not satisfied" to 5 as "very satisfied". The questionnaire also includes an item related to general satisfaction with the program, graded from 1 to 4.

Questionnaire for Volunteers. The APUNTATE Impact Questionnaire for Volunteers has also two sections. The first one anonymously collects personal information including degree and motivation to enroll in the volunteer program. The second part includes 47 items, graded 1 to 5, and grouped according to the same domains as in the questionnaire for users (see Table 4): Physical Capital, 12 items, (e.g. "level of satisfaction with support received by mentors and the rest of the team"); Human Capital, 11 items, (e.g. "personal development", "perception that their personal performance had a positive effect on others"), Economic Capital, 12 items, (e.g. "opportunity to access free training", "benefit for future career"), and Social Capital, 12 items, (e.g. "feeling of participating in the community"). Once again, an overall satisfaction item graded 1 to 4 was included.

Procedure

Questionnaires were distributed at the end of the academic year either through e-mail or via personal distribution. Questionnaires for users were completed by their parents or tutors.

Results

Families

Overall satisfaction and profile of impact. The overall satisfaction with the program was high for 92.2% of the families. The high rating of the program was also reflected in the small percentages of little/no satisfaction responses to items (8.9%). Data by capitals and items (Table 3) reveal higher mean scores in Physical and Economic Capitals.

Item-by-item analysis. The "quality of service" and the "access to service" were the most highly rated items. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of the Type of Capital [F (3, 228) = 27.77, p < .001]. T-test comparisons using the Bonferroni correction showed significant differences (p < .001) between Physical (M = 4.1, SD = .52) and Social Capitals (M = 3.8, SD = .44), as well as between Economic (M = 4.1, SD = .82) and Social Capitals (M = 3.8, SD = .44). Significant differences (p < .001) were found between Human Capital (M = 3.6, SD = .51) and all the others types of Capital: Physical (M = 4.1, SD = .52), Economic (M = 4.1, SD = .82) and Social (M = 3.8, SD = .44). Differences between Physical and Economic Capital were not significant.

The impact perceived was rated as high or very high by at least 70% of families in 17 out of the 38 items in the questionnaire (Table 3). Results were particularly positive in the case of "quality of service" (90.6% reported being very or quite satisfied). That supports were provided in the everyday context of the person with ASD and that they were individualized was especially valued. Families also highlighted the economic aspects, in the sense that they would not have been able to pay for such a service. An increase in the motivation of family toparticipate in supportprograms for people with autism/disabilities was observed. This was also the case for the motivation of users to perform and enjoy activities outdoors, the increase of opportunities to interact, and the trust on volunteer programs. Negative results were only found in relation to the interest of families to participate in other community activities.

Influence of personal variables. We conducted an ANOVA with three factors (age group, communication skills and behavioral flexibility) in order to explore the potential effects of these factors on general satisfaction expressed with the program. Group age and communication skills had three levels; behavioral flexibility had four levels according to the classification shown in Table 1. Both communicative and flexibility levels are based on the Autistic Spectrum Inventory (Riviére, 1997). In flexibility, we have kept the four original levels of the Inventory, but in communication we have combined levels 3 and 4 due to the lack of users with conversational abilities in our sample. Results show no main effect of age, flexibility or communication skills on user's satisfaction. However, a significant interaction was found between behavioral flexibility and age group (F (6,113) = 2.347; p = .036). Pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni correction showed that the families of users in the level 2 of behavioral flexibility (great resistance to change) were less satisfied with the program when they belong to the older group than when they belong to either the younger group (2.83 vs. 3.60; p = .044) or to the middle one (2.83 vs. 3.68; p = .028). That means that families of adolescents and adults with great problems dealing with change are satisfied with the program, but less than families of younger participants with a similar behavioral inflexibility.

Age. As mentioned earlier, we found no differences on general satisfaction among age groups. However, we compared the impact perceived in every area of each Capital, in order to assess those differences between age groups in which specific aspects could be considered as improved due to the program effect. We compared the global items (A, B and C) of each Capital using a one-way ANOVA. When differences in the global item were found, we compared the rest of the items of the area using the same method. We found no differences between age groups on items regarding Physical, Economic or Social Capital. However, considering the global items of Human Capital, an interaction effect between those items and the age group was found. Results showed differences between age groups on the global item regarding personal development (F (2,154) = 3.098; p = .048). Families of users in the youngest group report a higher contribution of the program to their personal development than the families of the oldest group (M = 2.68, SD = .468 vs. M = 2.45, SD = .50; p = .048). Taking into account the specific items of this area, we found an age group effect on the sense of self-esteem of users [F (2,146) = 3.190; p = .044], being greater the increase on sense of self-esteem on youngest users group that on oldest one (M = 2.571, SD = .499 vs. M = 2.326, SD = .518; p = .047). No significant differences were found between age groups on the item regarding the improvement on the user's capacity to express preferences, but results showed a significant effect of age group on the item regarding the user's motivation to do new things [(F(1, 150)= 5,449; p = .005]. As it was observed for self-esteem, the motivation to do new things increases more, due to the program effect, on the youngest group than in the oldest group (M = 2.771, SD = .423 vs. M = 2.468, SD = .504; p = .004). We also found differences between age groups on global item concerning the change on user's general abilities. The program seems to have a greater effect on general abilities of users from the youngest group than on users belonging to the middle group (M = 3.964, SD =.686 vs. M=3.531, SD = .581; p = .002) or to the oldest group (M =3.964, SD = .686 vs. M =3.49, SD = .618; p <.001). Focusing on specific items of this area, results showed a significant effect of age group on item regarding the user' daily Ufe activities [F(2,150)= 6.666; p = .002]. These activities, in the youngest group, seem to have changed more than in the users of the middle group (M = 2.482, SD = .504 vs. M = 2.224, SD = .421; p = .011) or the oldest group (M = 2.482, SD = .504 vs. M = 2.195, SD = .401; p = .004). Finally, no differences were found between age groups on global item regarding the user's general health and wellness.

Communication abilities. As mentioned earlier, no significant differences were found on overall satisfaction with the program related to this variable. We conducted one-way ANOVAs to analyze the differences on global items of each Capital related to users' communication abilities. No significant effects of communication abilities on the global items scores were found.

Behavioral flexibility. We conducted the same analysis of global items of each Capital considering behavioral flexibility. Results showed a significant effect of behavioral flexibility on the perception of the help received from the volunteer [F(3,148)= 3.273; p = .023]. Families of users on level 2 of behavioral flexibility showed less satisfied with the help received that families of users on level 3, that is, with less problems dealing with change (M = 2.625, SD = .659 vs. M = 2.90 SD = .295; p=.066). The analysis of specific items of this area showed no differences related to behavioral flexibility regarding the increase of leisure activities or in the availability of other resources from other organizations. However, we found marked differences on the item referring to the loss of opportunities if the service stopped [F (3,145) = 6.369; p < .001]. On this item, results showed a difference between the users on level 4 (with more behavioral flexibility) and the rest of users. That means that the service provides more opportunities to users on level 1 that to users on level 4 (M = 2.885, SD =.325 vs. M = 2.516, SD = .676; p = .010), and this pattern is repeated for users on level 2 (M = 2.833, SD =.461 vs. M=2.516, SD = .676; p = .029) and level 3 (M = 2.919, SD =.274 vs. M=2.516, SD =.676;p < .001). There were no significant differences on global items concerning Human, Economic and Social Capitals related to behavioral flexibility.

Influence of contextual variables: Recreational resources available in the community. We conducted a one-way ANOVA taking the resources available in the community as factor and the general satisfaction with the program as dependent variable. Results showed that differences on satisfaction with the program related to resources availability in the community does not reach the statistical significance, showing only a marginal probability [F (3, 152) =2.229; p = .087].

Considering the global items of each Capital, on Physical Capital we found differences related to resources availability on global item regarding level of innovation and creativity to adapt to the user's needs [F(3,153)= 3.821;p = .011]. Families of users with some resources in their community (Level 2) are more satisfied with this aspect than families of users who lack resources in their environment (Level 1), but these differences does not reach the statistical significance and only show a marginal probability (M = 2.785, SD = .516 vs. M = 2.368, SD =.830). This is the case too for families of users with sufficient resources available in their community (Level 3) (M = 2.848, SD = .364 vs. M = 2.368, SD = .830). The innovation to adapt to the user's needs seems to be easier, and to have a more positive effect, when there are some resources in the environment. This adaptation is not necessary when there is a great variety of resources (Level 4), but cannot be possible when there are no resources at all (Level 1).

Regarding global items of Human, Economic or Social Capitals, no significant differences were found.

Volunteers

Motivation. The main reason stated by the volunteers to enroll in this program was helping others in a 70% (n = 98) of cases. The remaining 30% stated they were enrolled to improve their own training.

Overall satisfaction and profile of impact. The overall satisfaction with the program reported by volunteers was very high for 50.9% of them and quite high for 43.9%. Only 4.3% responded they were little satisfied and 0.9% that they were not satisfied. Therefore, overall positive satisfaction can be said to represent 94.8%. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted that showed a significant effect of the type of Capital [F (3, 183) = 7.65;p < 0.001]. T-test comparisons using the Bonferroni correction showed significant differences p = 0.001) between Physical (M = 4.2, SD = 0.54) and Social Capitals (M = 3.9, SD = 0.46) and Physical (M = 4.2, SD = 0.54) and Human Capitals (M = 3.9, SD = 0.54).

Item-by-item analysis. The impact expressed by volunteers on individual items was rated as high or very high by at least 70% of users in 34 out of the 38 items in the questionnaire (see Table 4). In Physical Capital, 93.0% of volunteers were very satisfied or fairly satisfied with "access to training", "amount of information" (88.3%), "quality of information" (89.1%), "support received" by the team (90.4%), and the "knowledge of the volunteer's aims" by users (93.0%). With respect to Human Capital, volunteers recognized an increase in their "personal development" (89.2%), "feelings of being contributing to social improvement" (94.0%) and "perception that their personal performance had a positive effect on others" (95.2%). Concerning Economic Capital, the "lack of cost" (89.9%), "benefit" for future career (90.7%), and information about different routes to "professional development" (93.4%) were rated highly. Finally, in Social Capital, they recognized an increase in their "interest to participate in activities" related to disabilities/autism (88.6%), the "feeling of participating in the community" (85.9%) and "motivation to help others" (82.4%).

Influence of personal variables. We analyzed the relationship between satisfaction and impact of this program and two personal variables of volunteers: "type of degree" (Degrees related to Psychology, Education, Social Work and similar vs. Other Studies), and "motivation to participate in the program" (Helping Others or Improving Training). No significant differences were obtained in relation to degree neither in the reported main motivation, probably because the group of volunteers was relatively homogeneous on both these variables.

Discussion

The study reported here focuses on the issue of the impact perceived by families of people with ASD and university students after participating in a university program aimed at accompanying people with ASD in leisure activities (APUNTATE program). The study examines personal and contextual factors that, according to previous studies, can influence the perception of this impact, both when measuring the "overall satisfaction" of participants and when analyzing separately the impact on socalled "Physical, Human, Economic and Social Capitals" -Institute for Volunteering Research, 2004).

The APUNTATE program has been positively evaluated by its participants (92.5% of families of users and 94.8% of volunteers reported a very high or quite high overall satisfaction with the program). This high level of satisfaction has shown to be independent of the users with ASD's conditions (age, level of communicative competence, behavioral flexibility, and/or the leisure resources available in the community), as well as of the degree and main motivation to participate in the program of volunteers.

Consistently with previous studies (Moore & Allen, 1996; Phoenix et al., 2002; Fichten et al., 2005; Post & Neimark, 2007), our results allow us to conclude that the participation in this program has a very positive impact on both the professional prospects of volunteers and on their personal development. The excellent evaluation obtained, confirms the intrinsic value of providing opportunities to participate in social activities, and could be taken as evidence of possible benefits of future programs intended to promote the participation of people with ASD (Belinchón, Hernández & Sotfflo, 2008; García-Villamar & Dattilo, 2010).

Although it is not immediately obvious, part of the benefits perceived by the participant families are due to the individualized and naturalistic character of supports provided to users, as well as to the continuous training and support offered to volunteers. The adaptation to the users' individual needs, the fact that the accompaniment is carried out in every-day life contexts, and the volunteers' training and supervision have been proved to be especially important for families. On their side, volunteers valued most the training contents and its quality, the continuous supervision, and the accreditation that the Program offered them. All these factors, together with the lack of cost for both users and volunteers, could explain the high levels of satisfaction obtained.

Families of users with ASD perceived that carrying out social activities accompanied by volunteers had a very positive effect on the personal development of their sons and pupils, helping them to acquired new skills (i.e., daily life skills, interaction with other people, motivation to involve in activities outdoors, etc.). This high level of satisfaction with the Program's effects on these abilities was mainly perceived by the group of families of the youngest users, what is congruent with previous studies that found that age can negatively affect social participation (Newton & Honer, 1993; Orsmond et al., 2004; Kampert & Goreczny, 2007), and that a high percent-age of adolescents and adults with ASD have no friendly relations with peers (Orsmond et al., 2004). Specific studies with adolescents and adults are needed to exam this negative trend. Badia, Orgaz, Verdugo, Ullán & Martínez (2011) analyzed the influence of individual and environmental factors on the participation of youngsters and adults with developmental disabilities (people with Intellectual Disabilities and Cerebral Palsy) in leisure activities. They found that participation in social activities is more closely related to perceived barriers that to disability-related factors. In this vein, it is important to carry out studies with adolescents and adults with ASD. Besides, recently, Carter, Harvey, Taylor & Gotham (2013) are highlighting the promotion of a successful transition to community participation from educative contexts. They consider that students with ASD are leaving high school without the preparation and connections needed to engage meaningfully in their communities Programs like APUNTATE can help to promote this transition.

The improvement of the ability of users to actively participate by expressing their preferences and choices was also valued very positively. This result is of especial relevance, not only because it appears as related to an improvement in the level of communication abilities of users, but because it is one of the definition dimensions of current models of Quality of Life (Schalock, 1996).

Another interesting aspect that emerges from results obtained concerns the need to develop creative ways to promote social participations of people with an important behavioral inflexibility. Such a finding may be reflecting that communities are yet not prepared to offer resources for participation to people with major needs of support as people with ASD. Families have had repeated experiences of failure in social settings and the Program offers individualized support, well adapted to their needs, that gets to stimulate the participation within the familiar context. However, this effect it is not generalized to other settings.

On their hand, the high levels of satisfaction declared by the volunteers seem to be related to the close match between their motivations and the activities offered by APUNTATE. Most of the volunteers were majoring in courses related to Psychology, Education or attention to people with special needs (91.2%), being their main motivations (independently of their studies) to help others (70%) or to acquire extra training (30%). Moreover, according to Wardell et al. (2000), a highly structured organization, a rigorous process of selection, and the provision of continued training, support and supervision to volunteers, are the characteristics of the programs that better satisfy the goals of volunteers, being all of them characteristics that APUNTATE fulfilled.

The results of this study clearly suggest that the success and efficacy of volunteering programs supporting to leisure of people with ASD depend on several factors related both to the design of supports provided, and the structure of the Program itself.

First, the quality of the supports provided is of paramount importance to satisfy the users' expectations. They are better valued when (a) they are individualized, (that means, adapted to the users' personal conditions and needs); (b) they are carried out in their daily community environment; (c) they contribute to an improvement on skills, and (d) they enable the users to exercise their rights of self-determination and participation.

Second, the impact perceived by the volunteers is highly attached to the level of organization of the program, being the most valuable that (a) the program provides training and continued support, (b) the program facilitates an extended contact with people with ASD and their environment, (c) the program offers the opportunity to learn to anticipate and adequately respond (in technical terms, but also in terms of the ethics and attitudes) to the needs and preferences of people they provide support to, and (d) the participation in the program of students is formally and informally recognized, what improves their employment prospects.

The volunteers also perceived that their participation in APUNTATE had a very high impact on their personal development and skills (mainly on social and communication skills), on their career development (gaining experience and benefiting their employment prospects), and on the perception of their social contribution (feeling that they are active elements of social change, transforming and improving their community) .These perceptions also resulted in a change of attitudes that could be extended to the local community and other disabilities. Previous data (Belinchón, Henández & Sotillo, 2008) showed that, after participating in the program, volunteers diminished the negative stereotypes towards disability in general (and particularly towards ASD), increase the recognition of their social rights (a dimension also included in the Quality of Life model), and wanted to lead the society to a more inclusive philosophy.

Finally, the positive evaluation received points out to the convenience of keeping leisure programs apart from therapeutic interventions, as well as to the importance of focusing on individual needs rather than on the family requirements for respite. These aspects should be taken into account when organizing programs aimed to increase the social participation of people with ASD and other disabilities.

Conclusions

The organizations responsible for volunteer programs can benefit enormously from assessing in depth the impact of their activity, as has been previously shown by other studies (Esmond & Dunlop, 2004) and our own results also show. Specific assessment tools such as the Volunteering Impact Assessment Toolkit used in this study, that allow to identify the areas where the impact of the program is greater, or systematic analysis of records of the activities carried out daily by volunteers and users, give important clues for a better understanding of both users' and volunteers' needs and expectations. Consequently, it allows to create the conditions that may increase their level of satisfaction with the program, as well as to design new strategies and to optimize resources.

Universities have at their disposal the people (volunteer students, and families with a person with ASD), the opportunity to offer training and support by highly qualified professionals, and the capacity to provide official accreditation to training. Thus, Universities constitute privileged contexts to organize volunteer programs aimed to increase leisure and opportunities for social participation of people with ASD or other disabilities. These programs can facilitate a change of attitude towards people with disabilities that could be extended to the local community. And these programs can increase future employment prospects of students.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amparo Mosquera for her work adapting the Volunteering Impact Assessment Toolkit.

1 The term "impact" is used here to refer to the effect, generally positive, that an activity or program is on the condition of person after a period of practice

2 APUNTATE was sponsored by Obra Social de Caja Madrid and the participating universities, being free of charge for both users and volunteers. More information about the program itself can be found in Belinchón & Murillo (2006).

References

1. Badia, M., Orgaz, B. M., Verdugo, M. A., Ullán, A. M. & Martínez, M. M. (2011). Personal factors and percerved barners to participation in leisure activities for Young and adults with developmental disabilities, Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2055-2063. [ Links ]

2. Belinchón, M. (2001). Situación y Necesidades de las Personas con Trastornos del Espectro Autista en la Comunidad de Madrid. (Situation and Needs of People with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Community of Madrid). Madrid: Martin & Macías. [ Links ]

3. Belinchón, M., Hernández, J. M. & Sotillo, M. (2008). Personas con Síndrome de Asperger: Funcionamiento, Detección y Necesidades. (People with Asperger Syndrome: Functioning Detection and Needs). Madrid: CPA-UAM. [ Links ]

4. Belinchón, M. & Murillo, E. (2006). Apoyos universitarios a personas con Trastornos Autistas y Trastornos del Espectro: Programa APUNTATE. (University support for people with autism spectrum disorders: APUNTATE Program) In AETAPI (Ed.), Investigación e Innovación en Autismo. Premios "Ángel Riviére", segunda y tercera ediciones 2004-2006 (Research and innovation in autism. Angel Rivière Awards, second and third editions, 2004-2006) (pp. 168-206). Cádiz: AETAPI. [ Links ]

5. Buttimer, J. & Tierney, E. (2005). Patterns of leisure participation among adolescents with a mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 9, 25-42. [ Links ]

6. Carter, E. W., Harvey, M. N., Taylor, J. L. & Gotham, K. (2013). Connecting youth and young adults with autism spectrum disorders to community life. Psychology in the Schools, 50, 888-898. [ Links ]

7. Cowart, B. L., Saylor, C. F., Dingle, A. & Mainor, M. (2004). Social skills and recreational preferences of children with and without disabilities. North AAmerican Journal of Psychology, 6, 27-42. [ Links ]

8. Esmond, J. & Dunlop, P. (2004). Developing the volunteer motivation inventory to assess the underlying motivational drives of volunteers in Western Australia. Perth: Lotterywest & CLAN WA Inc. [ Links ]

9. Fichten, C. S., Schipper, F. & Cutler, N. (2005). Does volunteering with children affect attitudes toward adults with disabilities? A prospective study of unequal contact. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50, 164-173. [ Links ]

10. García-Villamisar, D & Dattilo, J. (2010). Social and clinical effects of a leisure program on adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54, 611-619. [ Links ]

11. Geisthardt, C. L., Brotherson, M. J. & Cook, C. C. (2002). Friendships of children with disabilities in the home environment. Education & Training in Mental Retardation & Developmental Disabilities, 37, 235-252. [ Links ]

12. González, V. & Extrema, N. (2010). Daily life activities as mediators of relationship between personality variables and subjetive well-being among older adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 124-129. [ Links ]

13. Hilton, C. L., Crouch, M. C. & Israel, H. (2008). Out-of-school participation patterns in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 554-563. [ Links ]

14. Houchhaser, M. & Engel-Yeger, B. (2010). Sensory processing abilities and their relation to participation in leisure activities among children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (HFASD). Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 746-754. [ Links ]

15. Hughes, C., Copeland, S. R., Wehmeyer, M. L., Agran, M., Xinsheng, C. & Hwang, B. (2002). Increasing social interaction between general education high school students and their peers with mental retardation. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 14, 387-402. [ Links ]

16. Institute for Volunteering Research (2004). Volunteering Impact Assessment Toolkit a Practical Guide for Measuring the Impact of Volunteering. London: Institute for Volunteering Research. [ Links ]

17. Kampert, A. L. & Goreczny A. J. (2007). Community involvement and socialization among individuals with mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28, 278-286. [ Links ]

18. Kolehmainen, N., Francis, J. J., Ramsay, C.R., Owen, C., McKee, L. & Rosembaum, P. (2011). Participation in physical play and leisure: developing and theory- and evidence-based intervention for children with motor impairments. BMC Pediatrics, 11 (100), 1-8. [ Links ]

19. Law, M., & King, G. (2000). Participation! Every child's goal. Today's Kids in Motion, 1, 10-12. [ Links ]

20. Law, M., Finkelman, S., Hurley, P., Rosenbaum, P., King, S., King, G. & Hanna, S. (2004). Participation of children with physical disabilities: relationships with diagnosis, physical function, and demographic variables. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11, 156-162. [ Links ]

21. Moore, C. W. & Allen, J. P. (1996). The effects of volunteering on the young volunteer. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 17, 231-258. [ Links ]

22. Murillo, E., López, I. & Belinchón M. (2008). El voluntariado universitario como recurso de apoyo y de formación: La experiencia del Programa APÚNTATE. (University volunteering as a resource for support and training: the experience of APUNTATE Program.). Revista Siglo Cero, 39, 63-79. [ Links ]

23. Newton, S. & Honer, R. (1993). Using a social guide to improve social relationships of people with severe disabilities. Journal of the Association for persons with Severe Handicaps, 18, 36-45. [ Links ]

24. Orsmond, G. I., Krauss M. W. & Seltzer M. M. (2004). Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 245-256. [ Links ]

25. Perry, T. L., Ivy, M., Conner, A. & Shelar, D. (2008). Recreation student attitudes towards persons with disabilities: considerations for future service delivery. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 7, 4-14. [ Links ]

26. Phoenix, T., Miller, K. & Schleien, S. (2002). Better to give than receive. Parks & Recreation, 37, 26-33. [ Links ]

27. Post, S. & Neimar, J. (2007). Why good things happen togoodpeople: The exciting new research that proves the link between doing good and living a longer, healthier, happier life. New York: Broadway Books. [ Links ]

28. Schalock, R. L. (1996). Quality of life. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation. [ Links ]

29. Solish, A., Perry, A. & Minnes, P. (2010). Participation of children with and without disabilities in social, recreational and leisure activities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23, 226-236. [ Links ]

30. Tinsley, H. E. & Eldredge, B. D. (1995). Psychological benefits of leisure participation: A taxonomy of leisure activities based on their need-gratifying properties. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 123-132. [ Links ]

31. Wardell, F., Lishman, J. & Whalley, L. J. (2000). Who volunteers? British Journal of Social Work, 30, 227-248. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Carmen Nieto.

Departamento de Psicología Básica.

Facultad de Psicología.

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

28049 Madrid (Spain).

E-mail: carmen.nieto@uam.es

Article received- 21-1-2013

Revision received 24-1-2013

Accepted 28-11-2013