Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Anales de Psicología

versão On-line ISSN 1695-2294versão impressa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.31 no.1 Murcia Jan. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.1.168581

Adaptation and psychometric properties of the SBI-U scale for Academic Burnout in university students

Adaptación y propiedades psicométricas de la escala SBI-U sobre Burnout Académico en estudiantes universitarios

Joan Boada-Grau1, Enrique Merino-Tejedor2, José-Carlos Sánchez-García3, Aldo-Javier Prizmic-Kuzmica4 y Andreu Vigil-Colet1

1 Universitat Rovira i Virgili

2 Universidad de Valladolid

3 Universidad de Salamanca

4 Escuela de Alta Dirección y Administración

ABSTRACT

The objective of the present study was to draw up a Spanish adaptation for university students of the School Burnout Inventory (SBI) 9-item scale. This entailed a double adaptation, on the one hand from English into Spanish and then from secondary school students to university students. The scale was applied to 578 university students (25.7% men; 74.3% women) from different regions in Spain. The findings indicate that the University students-SBI has the same structure as the original version in English for secondary school students. This was confirmed by factor analysis that pointed to the existence of three factors: Exhaustion, Cynicism and Inadequacy. Furthermore, the three subscales showed acceptable reliability (between .77 and .70) In addition to this, indications of validity were found using eighteen external correlates and seven contrast scales. Finally the SBI-U constitutes a potentially useful instrument for evaluating academic burnout in university students.

Key words: Academic burnout; SBI; university; Spanish version; instrumental study.

RESUMEN

El objetivo del presente trabajo ha sido desarrollar una adaptación española a estudiantes universitarios de la escala School Burnout Inventory (SBI) de 9 ítems. Así, se llevó a cabo una doble adaptación, por un lado, del inglés al español y, por otro, de estudiantes de secundaria a universitarios. La escala se aplicó a 578 estudiantes universitarios (25.7% hombres; 74.3% mujeres) de diversas zonas de España. Los resultados muestran que el SBI-Universitarios tiene la misma estructura que la versión original inglesa para estudiantes de secundaria, ello se ha constatado el mediante análisis factorial confirmatorio que ha indicado la existencia de tres factores: Agotamiento, Cinismo e Inadecuación. Por otro lado, las tres subescalas presentan una fiabilidad aceptable (entre .77 y .70). Además, se aportan indicios de validez a través de dieciocho correlatos externos y siete escalas de contraste. Finalmente, el SBI-U se configura como un instrumento potencialmente útil para evaluar el burnout académico en estudiantes universitarios.

Palabras clave: Burnout académico; SBI; universidad; versión española; estudio instrumental.

Introduction

In the mid seventies of the last century, Freudenberger used the construct burnout to define the deterioration process in the care and professional attention that users receive in services organisations such as healthcare and education centres, etc. Later on, Maslach (1976) referred to the burnout experienced by employees who provide services to people. Maslach and Jackson (1981) defined it as an inadequate response to chronic emotional stress, whose main features are physical, psychological and emotional exhaustion (emotional fatigue), a cold attitude towards others (depersonalization) and a feeling of inadequacy concerning the tasks they have to carry out (low personal fulfilment).

Burnout syndrome has been studied in many professions. The most prominent of these are healthcare workers such as nursing staff, physiotherapists and external emergency workers (Bernaldo & Labrador-Encinas, 2007; Figueiredo, Grau, Gil-Monte, & García, 2012), university professors (Otero, Santiago, & Castro, 2008), teachers (Pishghadam & Sahebjam, 2012), carers of the elderly (Menezes, Fernández, Hernández, Ramos, & Contador, 2006) and of minors (Jenaro-Río, Flores-Robaina, & González-Gil, 2007), council workers (Boada-Grau, De-Diego, & Agulló, 2004), traffic police (Aranda, Pando, Salazar, Torres, & Aldrete, 2009), prison officers (Hernández-Martín, Fernández-Calvo, Ramos, & Contador, 2006), firemen (Moreno-Jiménez, Morett, Rodríguez, & Morante, 2006) and state and private companies (Salanova, Grau, Llorens, & Schaufeli, 2001; Salanova, Schaufeli, Llorens, Peiró, & Grau, 2000; Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, 2002). Other collectives are currently being researched such as sports players (Arce, De Francisco, Andrade, Arce, & Raedeke, 2010) and adolescents (Salmela-Aro, 2012).

Numerous studies have applied the MBI-General Survey scale (MBI-GS) (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) to students, alt-hough it was originally designed to evaluate burnout in the general population. Research studies on academic burnout have basically focussed on students in healthcare. Key among these are the studies of medical students (De-Abreu, Grosseman, De-Oliva, & De-Andrade, 2011; Backović, Živojinović, Maksimović, & Maksimović, 2012; Costa, Santos, Rodrigues, & Vieira, 2012; Kains & Piquard, 2011; Prinz, 2012; Santen, 2010; Young, Fang, Golshan, Moutier, & Zisook, 2012), of nursing students (Botti, Foddis, & Giacalone-Olive, 2011), of odontology students (Campos, Jordani, Zucoloto, Bonafé, & Maroco, 2012; Divaris, Polychronopoulou, Taoufik, Katsaros, & Eliades, 2012), gynaecology and obstetrics (Nalesnik, Heaton, Olsen, Haffner, & Zahn, 2004), pharmacy students (Ried, Motycka, Mobley, & Meldrum, 2006) and physiotherapy students (González, Souto, Fernández, & Freire, 2011). Studies have also been carried out (Martínez, Marques, Salanova, & Lopes da Silva, 2002; Schaufeli et al.2002) with university students studying sciences, social sciences and humanities.

In addition to the above, Schaufeli, Martínez, Marqués-Pinto, Salanova and Bakker (2002) designed a specific burn-out scale for students, called the MBI-Student Survey (MBI-SS). This scale focuses on burnout due to the demands of studying as well as displaying an attitude of indiference towards ones studies, and feeling competent as a student. There have been studies carried out with university students (Adie & Wakefield, 2011; Gan, Shang, & Zhang, 2007; Martínez & Marques Pinto, 2005; Martínez et al., 2000-2001; Palacio, Caballero, González, Gravini, & Contreras, 2012; Rostami, Reza, & Schaufeli, 2012; Salanova, Martínez, Bresó, Llorens, & Grau, 2005).

Previous studies had been carried out in countries such as: Spain (Salanova et al., 2005; Martínez, Marques, Salanova, & Lopes da Silva, 2002), Portugal (Martínez & Marques Pinto, 2005; Martínez et al., 2000-2001), China (Gan et al., 2007), Colombia (Palacio et al., 2012), Iran (Rostami, Reza, & Schaufeli, 2012) and England (Adie & Wakefield, 2011).

Another more recent line of research is that initiated by Salmela-Aro et al. (2009), who designed and validated the School-Burnout Inventory scale (SBI-9). This instrument has been applied to students in higher education (university and non-university) from Finland (Salmela-Aro & Kunttu, 2010), to adolescent students from Spain (Moyano & Riaño-Hernández, 2013), from Peru (Merino, Delgadillo, & Caballero, 2013) and from Colombia (Aguilar-Bustamante & Riaño-Hernandez, 2013).

However, as some authors point out, (Caballero, Hederich, & Palacio, 2010; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Leskinen, & Nurmi, 2009) we need to construct and validate specific scales to evaluate academic burnout in particular. Hence, the contribution of this study is that it presents an instrument that enables us to evaluate academic burnout in university students given that a scale of these characteristics has never been published before in Spanish.

Following on from the above the present instrumental study (Montero & León, 2007) sets three objectives. Based on studies of burnout in job environments (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006) and in academic environments (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009; Salmela-Aro & Kunttu, 2010; Martínez et al., 2002, Schaufeli et al., 2002) it puts forward an academic burnout model for university students. In the first objective 1, the Salmela-Aro et al., (2009) academic model in Spanish is expected to have three factors: Exhaustion due to the demands of university work, Cynicism concerning the meaning of university, and A sense of inadequacy at university. As far as reliability is concerned, the Cronbach alphas are expected to be acceptable (objective 2) for all three factors, and finally, the convergent validity (objective 3) was checked by correlating the three academic burnout factors with various indicators such as social demographic data, irritation, psychological wellbeing, depression, personality, self-regulation and self-efficacy.

Method

Participants

The sample was made up of 578 university and post-graduate students from different Autonomous Communities in Spain. The data was gathered by three Spanish universities (Universitat Rovira i Virgili-Tarragona, Universidad de Salamanca and Universidad de Valladolid) and one EADA Business School (Escuela de Alta Dirección y Administración). 25.7% of the sample were men and 74.3% women (M= 21.6; SD=4.94). The types of studies were undergraduate (61.9%), diploma (28%), graduate studies (9%) and masters (1%). 49.9% of the sample were in their first year, 20% in the second, 9.2% in the third, 15.4% in the fourth, 25% in the fifth and 15% were on postgraduate or masters courses.

Instruments

- The School Burnout Inventory (SBI-9; Salmela-Aro et al., 2009) (See Annex 1) was drawn up for the purpose of evaluating burnout among adolescents in secondary education (16 year olds). The version we present has undergone a double adaptation. It was first translated from English into Spanish and the contents were then adapted from secondary school students to university students. The first adaptation was carried out following the steps set down in the scientific literature on adapting evaluation instruments (Muñiz & Bartram, 2007): Translation by experts of the items into Spanish, a discussion group on the translation of the items followed by their back-translation into English and a final check to make sure that the two versions are equivalent. Group techniques such as brainstorming and focus group were used in the second adaptation and were applied to various groups of university students. The scale consists of 9 items assessed on a Likert type scale (from 1= Completely disagree to 6= Completely agree) and 3 sub-scales (Exhaustion, Cynicism and Inadequacy). In order to distinguish it from the original version the Spanish version was labelled SBI-U.

- The Spanish version of the Irritation Scale (IS; Merino, Carbonero, Moreno, & Morante, 2006) consists of 8 items and 2 subscales. It enables us to diagnose irritation, which is defined as a state of progressive psychological fatigue that cannot be relieved with normal rest periods. Irritation may also arise when a person feels there is a discrepancy between a given state of affairs and their achievement of an important personal goal. The first subscale is called Emotional irritation (reliability = .86) and is made up of 5 items (for example, "3.-When other people talk to me it makes me irritated"); the second is called Cognitive irritation (reliability = .87) and is made up of 3 items (for example, find it hard to switch off after work"). The Likert responses were gathered using a 7 point scale (from 1.-Very much disagree to 6.-Very much agree) .

- The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Sanz & Vázquez, 1998) has been adapted into Spanish for university students. It enables us to evaluate general subclinical states of depression. It is a single factor scale with a reliability of .83. It is made up of 21 items that deal with sadness, pessimism, etc. and are assessed on a four-point Likert scale.

- The Overall Personality Assessment Scale (OPERAS; Vigil-Colet, Morales-Vives, Camps, Tous, & Lorenzo-Seva, 2013) is an instrument based on a model of the five big personality factors. According to this model, human behaviour depends mainly on five personality traits: Extraversion, Responsibility, Emotional Stability, Agreeableness and Openness to Experience. The scale consists of a total of 40 items, the responses to which are based on a 5-point scale. The factors are: Extraversion (alpha = .86; for example, "2.-I'm the life of the party"), Emotional Stability (alpha = .86; "32.-I often change mood"), Responsibility (alpha = .77; "5.-I always keep my word"), Amiability (alpha = .71; "12.-I respect others") and Openness to Experience (alpha = .81; "24.-I like trying out new things").

- The Self-Regulation Scale (SRS; Luszczynska, Diehl, Gutiérrez-Doña, Kuusinen, & Schwarzer, 2004) consists of 7 items which are answered using a four point scale (1= not at all to 4= a lot) and its configuration is one dimensional. Self-regulation is regarded as a dispositional variable that is responsible for being able to regulate oneself in a wide range of situations. Hence controlling alertness is a key component when it comes to overcoming obstacles. The scale's internal consistency in the different transcultural studies that have been carried out ranges between .63 and .87. Here is one example of an item: "7.-I keep focussed on my goals and do not allow anything to divert me from them".

- The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES; Sanjuán, Pérez, & Bermúdez, 2000) assesses the stable feeling of personal competency in coping effectively with a large variety of stressing situations. This is a one-dimensional instrument made up of 10 items with a 10-point response format (1= Completely disagree to 10= Very much agree) .An example of one item is: "5.-Thanks to my qualities and resources I can overcome unforeseen situations". The studies were carried out with samples featuring different nationalities and showed considerable internal consistency for the scale (between .79 and .93).

- Finally, we also used certain correlates, also known as external indicators (Streiner & Norman, 2008), in the form of questions that the respondents had to answer. One of them was answered using a scale of 10 anchors (1=Completely disagree to 10=Very much agree). These referred to support from tutors and professors, the class schedule load, the furniture and classroom conditions, and professor non-attendance of classes without prior notice. Others were answered providing specific details or stating how often they did certain things. For example, students were asked how often they had woken up at night thinking about things related to a certain subject, what they had studied over the weekends, etc.

Procedure

Non-probabilistic sampling was used, which is also known as random accidental sampling. Students participated on a voluntary and anonymous basis and their personal identification data was not registered. The data was always gathered inside the classroom on a group basis following the consent of the professor teaching the subject. An expert psychologist was always present during the application of the questionnaire to solve any possible queries that the university students might have.

Data Analysis

Taking into account that we already had a hypothesis concerning the questionnaire's factor structure, gven that the original version had put forward three factors, we carried out a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in order to verify this structure. Once the scale's factor structure was defined we used other scales and external indicators to analyse its reliability and criterion validity. The data were analysed using the programmes SPSS 19.0 and Mplus 5.1.

Results

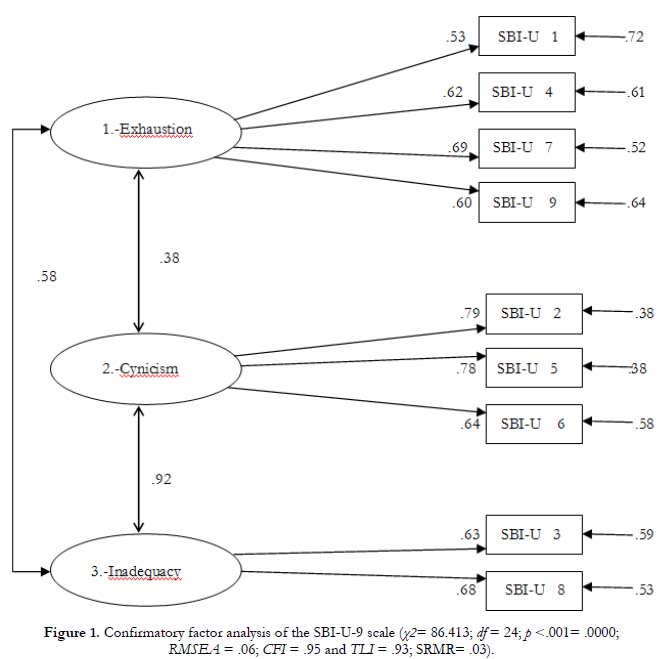

A CFA was performed on the polychoric correlation matrix given that the items seemed to be on an ordinal scale. We used the fit indices put forward by Hu and Bentler (1999), the comparative fit index (CFI), the non-normative fit index (NFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Although there is no absolute consensus, acceptable cut-off values for the first two tend to be equal to or above .90 whereas values below .08 were considered acceptable and equal to or under .05 excellent for the RMSEA (Browne & Cudek, 1993).

In our case the SBI-U showed an acceptable fit with the three factor model initially put forward by Salmela-Aro et al. (2009), and it came up with the following indicators: CFI = .95; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = .06 (90% reliability interval, .047 - .078; RMSEA approximate fit test <.05, p=.098). Consequently the indicator values were close to optimum.

Figure 1 shows the resulting model. Although we had initially considered a three factor structure, given the close relationship between two of them, we thought that a two factor model might be more suitable than the three factor structure. However, when the model was contrasted using CFA, creating a new factor by joining the items of factors 2 and 3, the model's fit decreased significantly (Δχ2 = 26.72; p <.001).

The questionnaire's dimensionality was established and Table 1 shows the scales' descriptive statistics, reliabilities and validity ratios. Reliability is between .70 and .77 which means that it can be considered acceptable if we take into account the small number of items that make up each of the subscales.

Table 1 also displays the correlations between the three scales and eighteen external correlates and five scales (Irritation, BDI, OPERAS, SRS and GSES). The three academic burnout factors (Exhaustion due to the demands of university work, Cynicism concerning the meaning of university and A sense of inadequacy at university) displayed relations with the different measures in the expected direction and correlated positively with irritation (emotional and cognitive) and general depression, whereas the third factor also showed a positive correlation with emotional stability (Sense of inadequacy at university). Furthermore, the three factors displayed negative correlations with extraversion, self-regulation and general efficacy. More specifically, we found different negative correlations such as between: Exhaustion concerning university work (F1) and emotional stability; Cynicism concerning the meaning of university (F2) and emotional stability, responsibility and amiability; and between A sense of inadequacy at university (F3) and responsibility, amiability and openness to experience).

As regards the external correlates, the three subscales that make up academic burnout were associated with various of these. We found three direct correlations, (for example, the number of the academic year, the Sundays they had devoted to studying, competition among colleagues, faculty absenteeism, etc.) plus nineteen inverse correlations (such as for example, support from tutors and professors, the class schedule load, level of comfort of furniture, transport, etc.).

Discussion

In the present study we present the psychometric properties of the SBI-U-9, a brief instrument that enables us to evaluate academic burnout (exhaustion, cynicism, inadequacy) in university students and this is the first time this scale has been presented in Spanish.

The findings from the confirmatory factor analysis of the SBI-U-9 support the three factor model (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, & Jokela, 2008) tested on a sample of Finnish teenage students (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009) and Spanish students (Moyano & Riaño-Hernández, 2013). The SBI-U-9 and MBI-SS scales have three subscales, whose contents are similar (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009; Schaufeli et al., 2002). We can therefore affirm that the study's first objective was totally confirmed.

The second objective was corroborated given that the reliability of the three factors was found to be appropriate.

Salmela-Aro et al. (2009) reliability ratios for the three subscales were: Exhaustion (.80), Cynicism (.80) and Inadequacy (.67). The ratios in the Spanish version were acceptable ranging between .70 and .77. Moyano and Riaño-Hernández's (2013), adaptation into Spanish the SBI, and tested on adolescents obtained similar reliabilities: Exhaustion (.57), Cynicism (.63) and Inadequacy (.49). As regards the MBI-SS (Schaufeli et al., 2002) the resulting reliabilities in university students for the three subscales that make up the scale were as follows: From .74 to .79 (Spanish), from .69 to .82 (Portuguese) and from .67 to .86 (Dutch).

As far as criterion validity is concerned, a review of the literature shows that burnout is related to irritation (Merino-Tejedor et al., 2006), depression (Ahola & Hakanen, 2007), personality (Hudek-Knezevic, 2011), self-regulation (Gurcay, 2009), self efficacy (Skaalvik, 2007) and certain external indicators (Salanova et al., 2000) such as age, profession, etc. The results of the present study found significant correlations between the three factors of the SBI-U scale and the abovementioned variables. They thus meet our objective in that they confirm the proposed validity ratios. In the study we are presenting what stands out primarily is the correlation between academic burnout and depression, which ranges between .29 and .41. Although the instruments used to measure depression were different, the association between academic burnout and depression was also found by Moyano and Riaño-Hernández (2013) in their research study, where the correlations ranged from .31 to .48.

By way of conclusion we can state that the SBI-U-9 scale's psychometric properties, in its Spanish version, are satisfactory. Thus, the CFA clearly confiráis the structure of the three original factors. Furthermore, the reliability estimates were acceptable and there is clear evidence of validity. We can consequently state that the present scale in Spanish is useful for evaluating academic burnout in university students.

The study has at least two drawbacks: On the one hand, more longitudinal studies need to be carried out in order to further determine the relationship between academic burn-out and other variables such as the year of the student's course (for example, the first year versus the fourth year), the number of repeat subjects, the type of repeat subjects (for example, education, psychology, medicine, engineering, economics, law, etc.), etc. Furthermore, the validation of a psychometric instrument is a dynamic process which does not end once it has been constructed and published (Padilla, Gómez, Hidalgo, & Muñiz, 2006). Hence new studies are likely to contribute new data both on academic burnout and on the scale we have presented. Finally, this study uses a convenience sample to adapt the scales and this limits the validity of the findings. Having said this, this is relatively common practice in research studies in the behavioural sciences (Alonso-Tapia & Rodríguez-Rey, 2012; Boada-Grau & Gil-Ripoll, 2011; Boada-Grau, Sánchez-García, Prizmic-Kuzmica, & Vigil-Colet, 2012). However, as Highhouse and Gillespie (2008) point out, quite often the use of incidental samples does not constitute an important threat to a study's validity and on the other hand, the present study, despite the fact that the sample is a convenience sample, incorporates students from different faculties.

References

1. Adie, J., & Wakefield, C. (2011). Perceptions of the teaching environment, engagement and burnout among university students on a sports-related degree programme in the UK. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 10, 74-84. [ Links ]

2. Aguilar-Bustamante, M., & Riaño-Hernandez, D. (2013). Propiedades psicométricas del "School Burnout Inventory" SBI en población colombiana adolescente (Psychometric properties of the "School Burnout Inventory" SBI in teenage Colombian population). Paper presented at the 34th Interamerican Congress of Psychology, 15-19 July, Brasilia (Brazil). [ Links ]

3. Ahola, K., & Hakanen, J. (2007). Job strain, burnout, and depressive symptoms: A prospective study among dentists. Journal of Affective Disorders, 104, 103-110. [ Links ]

4. Alonso-Tapia, J., & Rodríguez-Rey, R. (2012). Situaciones de interacción y metas sociales en la adolescencia: Desarrollo y validación inicial del Cuestionario de Metas Sociales (CMS) (Situations interaction and social goals in adolescence: Development and initial validation of the Social Goals Questionnaire). Estudios de Psicología, 33, 191-206. [ Links ]

5. Aranda, C., Pando, M., Salazar, J. G., Torres, T.M., & Aldrete, M. G. (2009). Social support, burnout syndrome and occupational exhaustion among Mexican traffic police agents. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 12, 585-592. [ Links ]

6. Arce, C., De Francisco, C., Andrade, E., Arce, I., & Raedeke, T. (2010). Adaptación española del Ahtlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ) para la medida del burnout en futbolistas (Spanish adaptation of Ahtlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ) to measure burnout in players). Psicothema, 22, 250-255. [ Links ]

7. Backović, D., Živojinović, J. I., Maksimović, J., & Maksimović, M. (2012). Gender differences in academic stress and burnout among medical students in final years of education. Psychiatria Danubina, 24, 175-181. [ Links ]

8. Bernaldo, M., & Labrador-Encinas, F. J. (2007). Evaluación del estrés laboral y burnout en los servicios de urgencia extrahospitalaria (Assessment of job stress and burnout in-hospital emergency services). International Journal of Clinicaland Health Psychology, 7, 323-335. [ Links ]

9. Boada-Grau, J., De-Diego, R., & Agulló, E. (2004). El burnout y las manifestaciones psicosomáticas como consecuentes del clima organizacional y de la motivación laboral (The burnout and psychosomatic manifestations consistent climate as orgamzational and work motivation). Psicothema, 16, 125-131. [ Links ]

10. Boada-Grau, J., & Gil-Ripoll, C. (2011). Measure of human resource management practices: Psychometric properties and factorial structure of the questionnaire PRH-33. Anales de Psicología, 27, 527-535. [ Links ]

11. Boada-Grau, J., Sánchez-García, J. C., Prizmic-Kuzmica, A-J., & Vigil-Colet, A. (2012). Work health and hygiene in the transport industry (TRANS-18): Factorial structure, reliability and validity. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 15, 357-366. [ Links ]

12. Botti, G., Foddis, D., & Giacalone-Olive, A. M. (2011). Preventing burnout in nursing students. Soins, 755, 21-23. [ Links ]

13. Browne, M. W., & Cudek, R. (1993). Alternate ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

14. Caballero, C. C., Hederich, C., & Palacio, J. E. (2010). El burnout académico: delimitación del síndrome y factores asociados con su aparición (The academic burnout: delineation of the syndrome and factors associated with its development). Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 42, 131-146. [ Links ]

15. Campos, J. A., Jordani, P. C., Zucoloto, M. L., Bonafé, F. S., & Maroco, J. (2012). Burnout syndrome among dental students. Revista Brasileira Epidemiologia, 15, 155-165. [ Links ]

16. Costa, E. F., Santos, S., Rodrigues, A. T., & Vieira, E. (2012). Burnout syndrome and associated factors among medical students: A cross-sectional study. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 67, 573-580. [ Links ]

17. De-Abreu, A. T, Grosseman, S., De-Oliva, E. F., & De-Andrade, T. M. (2011). Burnout syndrome among internship medical students. Medical Education, 45, 1146-1150. [ Links ]

18. Divaris, K., Polychronopoulou, A., Taoufik, K., Katsaros, C., & Eliades, T. (2012). Stress and burnout in postgraduate dental education. European Journal of Dental Education, 16, 35-42. [ Links ]

19. Figueiredo, H., Grau, E., Gil-Monte, P. R., & García, J. A. (2012). Síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo y satisfacción laboral en profesionales de enfermería (Burnout, work and job satisfaction in nurses). Psicothema, 24, 271-276. [ Links ]

20. Gan Y., Shang J., & Zhang Y. (2007). Coping flexibility and locus of control as predictors of burnout among chinese college students. Social Behavior and Personality, 35, 1087-1098. [ Links ]

21. González, R., Souto, A., Fernández, R., & Freire, C. (2011). Regulación emocional y burnout académico en estudiantes universitarios de Fisioterapia (Emotional regulation and academic burnout in university students Physiotherapy). Revista de Investigación en Educación, 9, 7-18. [ Links ]

22. Gurcay, D. (2009). Factors predicting teachers' collective efficacy beliefs. Journal of Education, 36, 119-128. [ Links ]

23. Hernández-Martín, L., Fernández-Calvo, B., Ramos, F., & Contador, I. (2006). El síndrome de burnout en funcionarios de vigilancia de un centro penitenciario (The staff burnout syndrome surveillance in prisons). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6, 599-611. [ Links ]

24. Highhouse, S., & Gillespie, J. Z. (2008). Do samples really matter that much? In C. E. Lance & R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Received doctrine, verity, and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 247-266). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

25. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. [ Links ]

26. Hudek-Knezevic, J. (2011). Personality, organizational stress, and attitudes toward work as prospective predictors of professional burnout in hospital nurses. Croatian Medical Journal, 52, 538-549. [ Links ]

27. Jenaro-Río, C., Flores-Robaina, N., & González-Gil, F. (2007). Síndrome de burnout y afrontamiento en trabajadores de acogimiento residencial de menores (Burnout syndrome coping workers and residential care for children). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7, 107-121. [ Links ]

28. Kains, E., & Piquard, D. (2011). The burnout of medical students. Revue Medicale de Bruxelles, 32, 424-430. [ Links ]

29. Luszczynska, A., Diehl, M., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., Kuusinen, P., & Schwarzer, R. (2004). Measuring one component of dispositional self-regulation: Attention control in goal pursuit. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 555-566. [ Links ]

30. Martínez, I. M., & Marques Pinto, A. (2005). Burnout en estudiantes universitarios de España y Portugal y su relación con variables académicas (Burnout in university students from Spain and Portugal and its relation to academic variables). Aletheia, 21 , 21-30. [ Links ]

31. Martínez, I. M., Marques Pinto, A., & Lopes da Silva, A.L. (2000-2001). Burnout em estudantes do ensino superior (Burnout in students of higher education). Revista Portuguesa de Psicologia, 35, 151-167. [ Links ]

32. Martínez, I. M., Marques, A., Salanova, M., & Lopes da Silva, A. (2002). Burnout en estudiantes universitarios de España y Portugal. Un estudio transcultural (Burnout in university students from Spain and Portugal. A cross-cultural study). Ansiedad y Estrés, 8, 13-23. [ Links ]

33. Maslach, C. (1976). Burned-out. Human Behavior, 5, 16-22. [ Links ]

34. Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement o experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99-113. [ Links ]

35. Menezes, V. A., Fernández, B., Hernández, L. Ramos, F., & Contador, I. (2006). Resiliencia y el modelo Burnout-Engagement en cuidadores formales de ancianos (Resilience and Burnout-Engagement model in nursing formal caregivers). Psicothema, 18, 791-796. [ Links ]

36. Merino, C., Delgadillo, A., & Caballero, R. (2013). ¿Burnout en adolescentes?: Validez estructural del inventario de burnout escolar (SBI) (Burnout in adolescents: structural validity School Burnout Inventory (SBI)). Paper presented at the 34th Interamerican Congress of Psychology, 15-19 July, Brasilia (Brazil). [ Links ]

37. Merino-Tejedor, E., Carbonero, M.Á., Moreno-Jiménez, B., & Morante, M-E. (2006). La escala de irritación como instrumento de evaluación del estrés laboral (The scale of irritation as an assessment tool of work stress). Psicothema, 18, 419-424. [ Links ]

38. Montero, I., & León, O. G. (2007). A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7, 847-862. [ Links ]

39. Moreno-Jiménez, B., Morett, N. I., Rodríguez, A., & Morante, M. E. (2006). La personalidad resistente como variable moduladora del síndrome de burnout en una muestra de bomberos (The hardy personality as a moderating variable of burnout in a sample of firefighters). Psicothema, 18, 413-418. [ Links ]

40. Moyano, N., & Riaño-Hernández, D. (2013). Burnout escolar en adolescentes españoles: Adaptación y validación del School Burnout Inventory (School burnout in Spanish adolescents: Adaptation and validation of School Burn-out Inventory). Ansiedad y Estrés, 19, 95-103. [ Links ]

41. Muñiz, J., & Bartram, D. (2007). Improving international tests and testing. European Psychologist, 12, 206-219. [ Links ]

42. Nalesnik, S., Heaton, J., Olsen, C., Haffner, W., & Zahn, C. (2004). Incorporating problem-based learning into an obstetrics/gynecology clerkship: Impact on student satisfaction and grades. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 190, 1375-1381. [ Links ]

43. Otero, J. M., Santiago, M. J., & Castro, C. (2008). An integrating approach to the study of burnout in University Professors. Psicothema, 20, 766-772. [ Links ]

44. Padilla, J. L., Gómez, J., Hidalgo, M. D., & Muñiz, J. (2006). La evaluación de las consecuencias del uso de los tests en la teoría de la validez (The evaluation of the consequences of test use in the theory of validity). Psicothema, 18, 307-312. [ Links ]

45. Palacio, J. E., Caballero, C. C., González, O., Gravini, M., & Contreras, K. P. (2012). Relación del burnout y las estrategias de afrontamiento con el promedio académico en estudiantes universitarios (Relationship of burnout and coping strategies with academic average in college students). Universitas Psychologica, 11, 535-544. [ Links ]

46. Pishghadam, R., & Sahebjam, S. (2012). Personality and emotional intelligence in teacher burnout. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15, 227-236. [ Links ]

47. Prinz, P. (2012). Burnout, depression and depersonalisation - psychological factors and coping strategies in dental and medical students. GMS Zeitschriftfür Medizinische Ausbildung, 29, 10-15. [ Links ]

48. Ried, L., Motycka, C., Mobley, C., & Meldrum, M. (2006). Comparing burnout of student pharmacists at the founding campus with student pharmacists at a distance. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 70, 114-126. [ Links ]

49. Rostami, Z., Reza, M., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2012). Dose interest predicts academic burnout? Interdisciplinari Journal of Contemporany Research in Business, 3, 877-885. [ Links ]

50. Salanova, M., Grau, R., Llorens, S., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2001). Exposición a las tecnologías de la información, burnout y engagement: el rol modulador de la autoeficacia profesional (Exposure to information technology, burnout and engagement: the role of self-efficacy training). Revista de Psicología Social Aplicada, 11, 69-90. [ Links ]

51. Salanova, M., Martínez, I.M., Bresó, E., Llorens, S., & Grau, R. (2005). Bienestar psicológico en estudiantes universitarios: Facilitadores y obstaculizadores del desempeño académico. (Psychological well-being in college students: Facilitating and hindering academic performance) Anales de Psicología, 21 , 170-180. [ Links ]

52. Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W.B., Llorens, S., Peiró, J.M., & Grau, R. (2000). Desde el "burnout" al "engagement": ¿una nueva perspectiva? (From the "burnout" to "engagement": A new perspective?) Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 16, 117-134. [ Links ]

53. Salmela-Aro, K. (2012). Gendered pathways in school burnout among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 89-95. [ Links ]

54. Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Pietikäinen, M., & Jokela, J. (2008). Does school matter? The role of school context for school burnout. European Psychologist, 13, 1-13. [ Links ]

55. Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J. E. (2009). School-Burnout Inventory (SBI) - Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25, 48-57. [ Links ]

56. Salmela-Aro, K., & Kunttu, K. (2010). Study burnout and engagement in higher education. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 38, 318-332. [ Links ]

57. Sanjuán, P., Pérez, A.M., & Bermúdez, J. (2000). Escala de autoeficacia general: datos psicométricos de la adaptación para población española (General self-efficacy scale: Psychometric data of adaptation to Spanish population). Psicothema, 12, 509-513. [ Links ]

58. Santen, S. A. (2010). Burnout in medical students: examining the prevalence and associated factors. Southern Medical Journal, 103, 758-763. [ Links ]

59. Sanz, J., & Vázquez, C. (1998). Fiabilidad, validez y datos normativos del inventario para la depresión de Beck (Reliability, validity and normative data for depression inventory Beck). Psicothema, 10, 303-318. [ Links ]

60. Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701-716. [ Links ]

61. Schaufeli, W. B., Martínez, I., Marqués-Pinto, A., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Studies, 33, 464-481. [ Links ]

62. Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. (2002). The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71-92. [ Links ]

63. Skaalvik, E. M. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 619-625. [ Links ]

64. Streiner, D. L., & Norman, G. R. (2008). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

65. Vigil-Colet, A., Morales-Vives, F., Camps, E., Tous, J., & Lorenzo-Seva, U. (2013). Development and validation of the Overall Personality Assessment Scale (OPERAS). Psicothema, 25, 100-106. [ Links ]

66. Young, C., Fang, D., Golshan, S., Moutier, C., & Zisook, S. (2012). Burnout in premedical undergraduate students. Academic Psychiatry, 36, 11-16. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Joan Boada-Grau.

Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona),

Centre de Recerca d'Avaluació i Mesura de la Conducta (CRAMC),

Carretera de Valls, s/n.

43007 Tarragona (Spain),

E-mail: joan.boada@urv.cat

Article received: 9-2-2013

Revision received: 7-8-2013

Accepted: 3-9-2013