Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.1 Murcia ene. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.1.229171

Corruption and Sexual Scandal: The Importance of Politician Gender

Corrupción y escándalo sexual: La importancia del género de un político

Magdalena Żemojtel-Piotrowska1, Alison Marganski2, Tomasz Baran3 and Jaroslaw Piotrowski4

1Gdansk University (Poland).

2Virginia Wesleyan College (Poland).

3Warsaw University (Poland).

4University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Poznan Campus (Poland).

ABSTRACT

The current experimental study analyzes individuals' reactions to politicians involved in scandals as a function of scandal type and politician sex (N = 798). Corruption and sexual scandals were considered. The results indicate that female politicians were judged more harshly than male politicians involved in scandals regardless of the type of scandal. Scandal affected not only assessment of their morality but also competence, contrary to assessment of men. The results were discussed in reference to expectancy violations theory and shifting standards theory which predicts more negative evaluation of women involved in immoral behavior despite lack general prejudices toward women in politics.

Key words: political scandal, gender stereotypes, expectancy violations theory, shifting standards theory.

RESUMEN

Esta investigación experimental analiza las reacciones individuales hacia los políticos involucrados en algún escándalo, según el tipo de escándalo y al género del político (N=798). Fueron considerados los escándalos sexuales y la corrupción. Los resultados indicaron que las féminas ligadas a la política fueron juzgadas con mayor severidad y recibieron peores críticas que los políticos masculinos, esto independiente del tipo de escándalo. Para las féminas, el escándalo no solo afectó a aspectos de su moralidad, sino también de su competencia profesional, algo que no pasa si el político es un hombre. Los resultados fueron discutidos dentro del marco de referencia de la teoría de incumplimiento de expectativas ("expectancy violations theory") y de la teoría de cambios en los estándares, las cuales predicen una evaluación y percepción mayormente negativa hacia las mujeres que se ven involucradas en algún tipo comportamiento inmoral, aun a pesar de que no exista prejuicio sobre la participación de las mujeres en la política.

Palabras clave: escándalo politicos; estereotipos de género; teoría de incumplimiento de expectativas; teoría de cambios en los estándares.

Introduction

A political scandal is any action or event involving a politician that is regarded as illegal, corrupt, or unethical and prompts general public outrage. Given the potential for political scandals to destabilize the status quo, the topic of political scandals has received attention from numerous scholars in psychology, political sciences, journalism or law. Regardless of the scientific disciplines, most studies focus on one type of scandal, mainly corruption or sexual (Cepernich, 2008; Maier, 2011; Puglisi & Snyder, 2011; Wiid, Pitt, & Engstrom, 2011) and on male politicians in established democracies (Berinsky et al., 2010; Kumlin & Esaiasson, 2012; Maier, 2011; Vivyan, Wagner, & Tarlov, 2012). In this research, we focus on how reactions to politicians involved in scandals might differ as a function of the type of scandal and the gender of the politician while also considering factors that may be responsible for influencing electability.

Politician involvement in scandals

Political scandals can be particularly offensive situations whereby an individual possessing a public position violates a constitutional order, i.e. norms regulating the use of power; (Neckel, 2005; Thompson, 2000). Scandals may disrupt moral foundations by going against societal expectations, and they can be especially dangerous to political image, lessening support for those who are involved (Maier, 2011). Further, scandals have the potential to influence politicians' likeability and electoral chances (Vivyan, Wagner, & Tarlov, 2012). Since a politician's image is significantly based on assessment of their moral traits (Wattenberg, 1991), and morality (together with competence) dominates in our assessment of others (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014; Brambilla, Rusconi, Sacchi, & Cherubini, 2011) including perceptions of politicians (Bertolotti, Catellani, Douglas, & Sutton, 2013; Wojciszke & Klusek, 1996), scandals can negatively influence individuals' views of transgressors and dampen support from voters.

Two theories offer explanation as to why scandal involvement may differentially impact male and female politicians on assessment and electability: expectancy violations theory (Burgoon, 1978; Jussim, Coleman, & Lerch, 1989) and shifting standards theory (Biernat 2003; Biernat & Manis, 1994). Expectancy violations theory assumes that people have various expectations about how others should think and behave (Burgoon, 1978). Violations of expected behavior results in negative moral evaluations (Jussim, Coleman, & Lerch, 1989), uncertainty, and lower credibility ratings (Burgoon & Hale, 1988). Although this theory refers to communication (verbal and non-verbal), it could be used to assess particular behaviors including political acts (see Smith, Smith Powers, & Suarez, 2005). Shifting standards theory offers more in-depth predictions about how the same act could lead to more or less negative assessment, depending on personal characteristics of offenders (Biernat, 2003).

One of the most important personal characteristics of a politician is gender, and, related to it, gender role expectations and stereotypes (see e.g. Eagly, 1987; Fiske, Haslam, & Fiske, 1991; Wiliams & Best, 1990), which provide standards for assessing others as assumed by shifting standards theory (Biernat, 2003; Biernat & Manis, 1994) and which has been visible in leadership roles (Eagly & Karau, 2002). The abovementioned theories complement one another and, taken together, offer a plausible explanation for the impact of scandal involvement on politicians' assessment as it relates to their gender. The first focuses on the content of stereotypes, which is the source of expectations that could be violated by politicians and result in their negative assessment on particular dimensions. It also addresses the issue of cultural context of assessment. The second assumes that assessment of political misconduct performed by women and men could be the effect of using different standards for evaluation, explaining to what extent the image of politicians may be disrupted by scandal involvement. Additionally, it addresses the issue of personal beliefs of the assessor. In sum, the first answers the question regarding which dimension is important for assessment and the second answers the question how this dimension may be used to assess both sexes.

Politician gender and assessment of transgressors

Previous research has found that female politicians are affected by gender stereotypes (Johns & Shepard, 2007; Sanbonmatsu, 2002). Gender stereotypes do not directly affect women's electability and expectations toward women and men in politics are quite similar (Brook, 2014; Dolan, 2014) and stereotypes of women (but not men) in politics are different from general gender stereotypes (Schneider & Bos, 2014). Despite this recently described lack of overt prejudice toward women in politics, the question whether women and men involved in political scandals are assessed in similar ways is still worth of investigation. Since gender stereotypes in politics presume that females are honest (Kahn, 1992), this expectation could lead to more rigid standards in assessment of immoral behaviors of women (see Biernat, 2003). When combined, expectancy violations theory and shifting standards theory may provide a possible explanation for this effect. Expectancy violations theory assumes that the same immoral act will be judged differently when committed by a woman versus a man due to different expectations that exist toward both sexes. According to shifting standards theory (Biernat, 2003; Biernat & Manis, 1994), different standards of evaluations exist for certain groups members, and these members tend to be assessed in reference to the standards prescribed to that particular group. There could be higher standards for moral behavior of women, so the same immoral act will be assessed more negatively when a female politician is involved compared to a male. Integrating both theoretical frameworks, we argue that scandals can result in a disproportionately large loss of support for female politicians who are involved in them.

Emerging research has begun to investigate politicians' gender and how it may relate to individuals' perceptions, but it has nevertheless offered inconsistent and complex results (McGraw, Timpone, & Bruck, 1993; Ogletree, Coffee, & May, 1992; Smith, Smith Powers, & Suarez, 2005; Stewart et al., 2013). For instance, older studies examined politicians' sex and revealed that women involved in scandals suffer less negative effects than males (e.g. Ogletree, Coffee & May, 1991), yet other research has pointed to the harsher treatment of female politicians (McGraw, Timpone, & Bruck, 1993). Some studies have even suggested that the sex of a politician plays no obvious role (Bhatti, Hansen, & Leth, 2013; Smith, Smith-Powers, & Suarez, 2005).

As Biernat & Manis (1994) suggested, the effects predicted by shifting standards theory are present mostly among people who believe in sex stereotypes. For this reason, it is possible that female politicians involved in scandals would be treated more harshly than men, if participants endorse sex stereotypes. Therefore, it is important to measure the belief about the capacity of men versus women in politics.

Expectancy violation theory supplements shifting standard theory by indicating the importance of cultural and political context in which the assessment of behavior is performed. The most important recent works on gender stereotypes are reported for American society (Brooks, 2014; Dolan, 2014). However, little known about political contexts other than that of the United States and its relation to perceptions of women and men in politics. The post-communist context sets the specific conditions in relation both to gender stereotypes and to scandal perception. Although the former communist system did not discriminate against women in their professional careers, the actual number of women in politics was rather low and they were not encouraged in the political arena (Siemieńska, 1994). Currently, their political representation is similar to that reported in democratic countries without a communist past. For instance, women make up 24.35% of members in the Polish parliament and they also represent 19.35% of those in the U.S. Congress (Interparliamentary Union, 2015). The more serious differences are visible in perceptions of political systems. In postcommunist countries, trust toward politicians is low and political class is perceived as dishonest and corrupted (Johnson, 2005; Puchalska, 2005). For this reason, the standards for evaluation of politicians' honesty could be lower than in established democracies, regardless a politician sex.

The current study

The primary purpose of this research is to examine individuals' perceptions of politicians involved in scandals and whether they differ based on the type of scandal and/or the politicians' sex. Currently, research on the impact of politician sex and misconduct offers inconsistent findings, potentially due to the lack of diverse samples, lack of control for level of prejudice, and lack of control for severity in scandal type. To address these problems, we used an experimental design for the direct examination of possible differences in reactions to male and female politicians' misbehavior in differing types of scandal scenarios. We based our predictions on assumptions derived from integration of expectancy violations theory and shifting standards theory. In order to add current knowledge to the field and shed light on ambiguous results, we also examined attitudes toward women in politics (e.g. whether people believe that they are worse than men in political roles), and we concentrated on scandals involving corruption and sexual misbehavior due to the regularity of their occurrences in political world (Puglisi & Snyder, 2011). We also controlled for the severity of scandalous situations, focusing on serious scandals only as they have a stronger impact on political image.

Additionally, we included assessments of morality and competence as dependent variables due to their importance in shaping people's perceptions of politicians (Brambilla et al., 2011; Wojciszke & Klusek, 1996) including gender stereotypes in politics, as competence, integrity and having moral traits have been seen as important in assessing politicians (Schneider & Bos, 2014). Last, we included assessment of electoral chances and assessment of the extent to which politician could represent voters' interests, as both variables are important when considering politician sex. As Sanbonmatsu (2002, 2005) noted, women are believed to have lower electoral chances; therefore, not voting for them may be seen as more rational than doing it. Self-interest, on the other hand, is related to assessment of politicians' morality. Assessment of morality becomes higher when people believe that the assessed individual acts on their behalf. Alternatively, when people believe that the assessed individual acts against their self-interest, assessment of morality declines (Cislak & Wojciszke, 2006). The belief that women or men will better represent voters' interests is also an important factor in gender-based voting decisions (Sanbonmatsu, 2002).

Since corruption and sex scandals are congruent with "male" stereotypes (Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993), and voters expect women to be more honest and rigid in fulfilling moral standards (Kahn, 1992), it is predicted that voters would have lower standards for male morality and higher standards for female morality (Biernat, 2003) and they expect immoral behaviors from men over women, in line with expectations violation theory (Burgoon, 1978; Jussim, Coleman, & Lerch, 1989). By this logic, scandals would be more destructive for women than men. While Smith and colleagues (2005) did not find support for this hypothesis, it may be due to limitations inherent in their study. First, they used various types of scandalous scenarios, with abuse of power as confounding variable. Second, they did not control the severity of scandals in a pilot test. In an attempt to address these issues, we focus on serious scandalous situations related to abuse of power. Further, Smith et al. (2005) used one general assessment measure, which included statements related to both competence and morality combined, so it is difficult to determine whether scandals affect assessments of men and women in the same way on both dimensions. It is expected that politicians' characteristics assessments on morality and competence will mediate the relationship between politician scandal involvement and electability, although specific predictions are not made due to the limited understanding of this in the research base.

Method

Pre-test Study 1. In the first pilot study, Study 1, 24 participants (12 men and 12 women) who were recruited from a local community and ranged in age from 32 to 52 years old were asked to provide assessments of scandalous situations. In particular, they were asked to assess three aspects of a scandal: to what extend described action is (1) immoral, (2) socially destructive, and (3) negative. Descriptions were written in the form not allowing for identification of the transgressor's sex or age. They contained 3-4 sentences describing the politician's position (e.g. deputy, senator, etc.) and action (e.g. a sexual proposal toward subordinates). Information stating that the situation was under investigation and denial of any involvement on behalf of the politician were also included. Each participant assessed only one type of scandal on three dimensions (i.e., immoral, socially destructive, negative) with each scale ranging from 1 - absolutely no, to 5 - absolutely yes. Based on these evaluations, one description of a corruption scandal and one of a sexual scandal were chosen, so that the evaluations of both situations were balanced. For assessment of immorality, the mean score for a sexual scandal was M = 4.54 (SD = 0.93) and the mean score for a corruption scandal was M = 4.58 (SD = 0.60), t(23) = -0.25, p = .401. The assessment of social destructiveness revealed M = 4.42 (SD = 0.88) for a sexual scandal and M = 4.54 (SD = 0.72) for scandal involving corruption, t(23) = -0.72, p = .239. Last, the mean for assessment of negativity was M = 4.54 (SD = 0.78) for a sexual scandal and M = 4.58 (SD = 0.65) for a corruptive one, t(23) = - 0.27, p = .394.

Pre-test Study 2. A manipulation check was done independently in Study 2 with the scenarios used in the main study. In this pilot study, 277 individuals (53% men) in age from 25 to 60 participated. All data were collected anonymously. Participants were offered extra points in the research panel's loyalty program that they could exchange for small gifts. Participants were randomly invited to take part in the study. Basic demographic characteristics were controlled to reflect characteristics representative of Polish Internet users. We excluded 14 participants (5%) due to giving accidental answers (all answers denoting "no opinion") and 29 subjects who answered that they were familiar with situation (in fact, each story was artificial). After reading the scandalous situation description, participants were asked to assess (on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 - definitely not a scandal to 7 - definitely a scandal) whether the described situation could be labeled as a scandal.

In order to check if both scandalous situations were perceived as scandals and if politician sex did not affect the extent to which participants assessed this situation as a scandal, one-way ANOVA was performed. There was main effect of scandal, F(2, 239) = 115.06, p < .001, ŋ2 = 0.50. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction revealed no difference between sexual (M = 5.24, SD = 1.27) and corruption (M = 4.91, SD = 1.31) scandals, n.s., and they both differed from a neutral situation (M = 2.36, SD = 1.01),p < .001. Sex of politician did not affect assessment of situation as scandalous, F(1, 239) = 0.62, n. s. Thus, both types of scandalous situations were perceived by the subjects, to the same extent, as a scandal.

Participants and procedure

The present study followed the two pilot studies. It was conducted with a heterogeneous sample of individuals living in Poland. Eight hundred and sixty-seven participants were recruited by use of Ariadna, an online research panel. All data were collected anonymously. Participants were offered extra points in research panel's loyalty program that they could exchange for small gifts.

A 3 x 2 experimental design was used that included varying scandal types (i.e., corrupt vs. sexual vs. control group) and politicians' sex (male vs. female). The participants' sex was not included in the design, as the preliminary analyses found no significant effect for it. This may indicate that men and women hold similar beliefs/view about politicians, even if the views they have differ as a function of politician sex. Each participant assessed only one type of scandal. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental conditions. They first answered questions related to personal demographic data (e.g. age, sex, level of education), then answered questions about attitudes toward women in politics, and subsequently read the scenario describing the politician and his/her involvement in a scandal. They were then asked for their assessment of the politician.

Data from 798 participants were used for final analysis (N = 798). Participants under the age of 18 years were excluded, along with those who gave accidental responses (i.e. choosing only 4 denoting "I have no opinion" in all questions and measures), and with time reactions exceeded +/- 3 SD. Males comprised over half the sample (55.8%), and the age of participant ranged from 18 to 77 years old (Mage = 31.52, SD = 12.91). Regarding education, 10.0% had elementary education, 41.4% secondary level education, 22.4% high school education, and 26.2% had an academic education (BA or MA). All participants were Poles.

Materials

Politicians' gender. The politicians' gender was predetermined in the scenarios provided to participants, with each participant being randomly assigned to either a male or female politician and assessed only one type of politician.

Type of scandal. The type of scandal conditions included corruption, sexual misbehavior, and a control group of no scandal. Each description contained information about politician's name, the family name, age (42), education (high, foreign trade MA gained at local university), and a short 2-sentenced account about the scandalous situation that occurred (i.e., corruption, sexual, or none). The corruption scandal condition involved a scenario where the politician accepted a financial bribe from an external source in exchange for changing the status of land from agrarian to utilitarian, resulting in higher worth of this land. The sexual scandal condition consisted of a situation where the politician made sexual proposals to subordinates. In both conditions, the description contained information about a pending prosecutor investigation and the refusal to admit to any wrongdoing by the politician. In the control group, the same description of the politician was provided, but no scandalous situation was mentioned.

Measures

Assessment. We concentrated on two aspects regarding the impact of scandalous situations: the possible negative impact on citizens' voting decisions and the impact on two separate aspects of evaluation: morality and competence. Participants were asked to what extent the politician could be described in terms of positive characteristics relating to morality and competence, each on 7-point scale (1 - completely not to 7 - absolutely yes). The list of traits was taken from Self-Assessment Questionnaire, which served as a measure of self-esteem in competence and morality domains by B. Wojciszke (personal information); seven were related to morality (i.e. loyal, disinterested, honest, upright, truthful, just, frank), and seven to competence (organized, consequent, effective, smart, clever, energetic, efficient). The reliability of the scales used to assess morality and competence were .92 and .87 (Cronbach's alpha), respectively. Exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation (two factors a priori assumed) revealed that morality and competence established separate factors (Eigen value for morality factor was 5.48 and competence factor 4.94, together they explained 74.45 % of variance).

Electability. After reading all the information, participants were asked about their willingness to vote for the described politician, to what extent such person could be a good representative of their interests, and how they assess the electoral chances of this politician (1 - definitely no to 7 - definitely yes). As all these items were highly correlated, so we decided to combine them in one measure labeled electability. The reliability of this measure was α = .91.

Attitudes toward women in politics. Opinion about the capacity of women versus men in politics was measured by asking respondents to complete a single item question: In your opinion, are women in politics? (1- significantly less capable than men, to 4- equally capable as men, to 7 - significantly more capable than men). In general, women were believed to be less capable than men by 17.3% of respondents, 69% admitted no differences between sexes, and 13.6 % believed in higher capacity of women.

Results

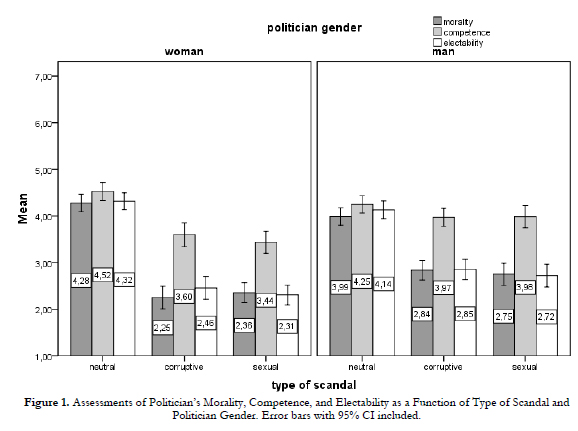

In the current study, multifactorial ANOVA tests were performed for the 2 (politician gender: male vs female) by 3 (type of scandal: corruption vs sexual vs neutral condition) experimental design for assessment of morality, competence and electability. The effects of politician gender and involvement in scandals are reported at Figure 1. All analyses were performed with controlling the impact of attitudes toward women in politics.

Participant sex and its impact on assessment of politician

There was no effect of participant's sex on competence assessment, F(1, 786) = 0.87, n. s., morality assessment, F(1,786) = 0.28, n. s., or electability, F(1, 786) = 2.05, p = .153. Also, all interactions between participant's sex and politician's gender were insignificant (all Fs < 1), as well as interactions between participant's sex and type of scandal (all Fs < 1).

Morality assessment

The politician's gender directly affected morality, F(1,786) = 7.22, p = .007, ŋ2 = .01, but congruent with predictions, interactions between politician's gender and scandal were also significant, F(1, 786) = 9.86,p < .001, ŋ2 = .02. To answer the question if women are assessed more harshly than men in scandalous scenarios, planned contrasts analyses were performed (with both scandalous situations given opposite weights than neutral condition). Analysis shows a significant difference between morality assessment in the scandalous situation for women (M = 2.31, SD = 1.21) and men (M = 2.80, SD = 1.27), t(447.70) = - 4.31, p < .001, d = -0.40. However, in the neutral condition women were assessed as more moral than men, t(313) = 2.20, p = .029. There were no differences between two types of scandals for assessment of men morality, t(241.40) = 0.54, p = .933, and women morality, t(209.26) = -0.64, p = .526.

Competence assessment

The politician's gender affected also competence, F(1,786) = 6.27, p = .012, ŋ2 = .01, but congruent with predictions, again interaction between politician's gender and scandal were significant, F(1,786) = 6.27, p = .012, ŋ2 = .01. To answer the question if women are assessed more harshly than men in scandalous scenarios, planned contrasts analyses were performed (with both scandalous situations given opposite weights than neutral condition). Women's competence (M = 3.51, SD = 1.31) was also assessed as lower than men's (M = 3.98, SD = 1.22), t(792) = - 4.02, p < .001, d = - 0.29. However, in the neutral condition women were assessed as more competent than men, t(313) = 2.02, p = .044. Again, the scandal type was no impact on assessment of competence for men, t(792) = -0.08, p = .574, and women, t(792) = 0.98, p = .329.

Electability of politicians

Analyses detected main effect of politician gender for electability, F(1, 786) = 5.30, p = .005, ŋ2 = .01 and interaction between politician gender and scandal type, F(1,786) = 6.01, p = .014, ŋ2 = .01. Planned contrasts analysis revealed that in scandalous situations voters declared higher support for men (M = 2.80, SD = 1.32) than for women (M = 2.37, SD = 1.22), t(447.78) = 3.56, p = .001, d = 0.34. However, in the neutral condition there were no gender differences for electability [t(313) = 1.39, p = .166]. Again, there were no differences for electability between two scandalous situations for men, t(241.32) = 0.80, p = .393, and for women, t(207.88) = 0.92, p = .358.

Discussion

Based on our unified view of expectancy violations theory and shifting standards theory, we analyzed and interpreted the effects of scandal on political image and electoral chances of politicians with respect to their gender. We focused on two types on scandals (i.e., corruption and sexual), which were serious violations of social norms, and we controlled the impact of personal attitudes toward women in politics. Further, we examined the impact of scandal on politician assessment on two fundamental dimensions (i.e., morality and competence).

Turning to focus on theory, both of those identified assume that women are assessed more harshly when they are involved in scandals than their male counterparts: due to higher levels of expectations of their honesty (expectancy violation theory) and more rigid standards for assessment of their morality (shifting standards theory). Shifting standards theory assumes the importance of personal beliefs of voters in assessment of misconducts, which is why we controlled for personal attitudes toward women in politics. Further, based on expectancy violation theory, we predicted that cultural context will play an important role in the assessment of scandals (i.e., the impact of scandal on assessment will be generally rather low, regardless of politician sex).

As expected, the findings of current research contradict the results that have been reported by Smith et al. (2005), but they confirm the assumptions derived from expectancy violation theory and shifting standards theory when taken together. Congruent with our hypothesis, the results suggested that female politicians involved in scandals were assessed less favorably on all dimensions (i.e., electability, morality, and competence) when compared to male politicians. For male politicians, involvement in scandals did not affect competence assessment, contrary to what was found for the women.

Because we focused on serious scandals, the findings of current study differ from studies on less serious norm violations such as those dealing with controversies. When women are involved in more visible norm violations, a contrast effect may be more likely to appear (see Biernat, 2003; Mos-kovitz, 2005), resulting in more negative assessments of female politicians. Thus, in line with some research (Stewart et al., 2013), this might point to the importance of studying the severity of norm violating behaviors as well as social group comparisons in the future.

The impact of scandal involvement on assessment of morality and competence could be explained by different standards and expectations toward women and men in politics. Since females may be perceived as more moral than men (Kahn, 1992), as found also in the neutral condition of current study, they may be held to by higher standards (Biernat, 2003). When they are found to be in violation of these expectations, they are judged more harshly. In contrast, since men are more commonly seen in politics and observed in media cases of political scandals (Thompson, 2000), they may already be expected to be involved in such acts when compared to female politicians. Overall, the results indicate that female politicians involved in scandals are assessed more negatively than male politicians who engage in the very same behavior, and this is congruent with the old findings of McGraw, Timpone, and Bruck (1993).

Naturally, one could expect that the observed differences in results could be caused by different cultural context (i.e. United States versus Poland). However, in the neutral condition, we found sex differences in morality assessments similar to these reported by Kahn (1992) and Schneider and Bos (2014). Cultural context did not influence the expectations toward women and men in politics, but it influenced the impact of scandal involvement on assessment. Generally, all effect sizes were rather low, pointing lower expectations toward politicians' honesty, regardless of their gender.

The findings of this research study could be useful in explaining the interaction between politician gender and scandal type. On a general level, women in politics are assessed in a positive light when they are not involved in any type of scandal, their electability is not affected by gender stereotypes (Brooks, 2014; Dolan; 2014), and the expectations toward them are similar to men (Schneider & Bos, 2014). However, when a woman violates what is expected of her (i.e., sexual and corruptive scandal), she is considered more flawed (i.e., less moral and less competent), which highlights more subtle inequities that may exist.

The negative effect of transgressions on female politicians' image is probably the cost of higher ethical standards expectations, which is congruent with shifting standard theory predictions. So, while research suggests that one's sex does not influence the chances of being elected to office (Ford, 2002), there may be a hidden barrier to having them actually getting in. When placing that in the context of this research, it shows that women in politics are seen just as favorably, if not more, than males when they have not violated any expectations (i.e., control group). This research shows women are more disadvantaged in regard to perceptions when involved in the same unethical acts as their male counterparts. While public attitudes about gender roles generally have changed to support women into office (Brooks, 2014; Dolan, 2014), they may not have changed when it comes to judgment placed on their behavior.

The described findings have not only theoretical meaning, but they also allow for predictions when face saving endeavors of offenders will have a chance for successful realization. Women are initially perceived as more moral, as the results pointed to (again, see Kahn, 1992), but in line with expectancy violations theory and shifting standards theory, these higher expectations lead to more negative assessment of women involved in the very same behavior as men, which may make it more difficult for their redemption. For this reason, women need to invest more effort to manage their political image when they are involved in scandals and perhaps any negative behavior. As our study suggests, scandals affect not only assessment of their morality, but also of their competence. Therefore, female politicians especially need to pay attention to managing public image should scandals emerge.

Limitations and suggestions for further work

It should be noted that the effects in the present experiments were generally very weak, but it is congruent with theoretical predictions and it was partially the result of the sample size. Therefore the interpretation of current findings should be made with caution. Because our study was conducted in a post-transitional society, our results could be affected by political context. In the post-communist countries, politicians are perceived as immoral and corrupt, as the level of interpersonal and political trust is low and social cynicism level is high (Boski, 2010; Johnson, 2005; Puchalska, 2005). However, in the United States, people may expect honesty and moral virtues from their political leaders (Basinger & Rottinghaus, 2012). Despite cultural differences, we expect that the basic mechanisms operate and remain the same for established democracies and post-transitional countries. Nevertheless, since most studies pertaining to political scandals have been conducted in English-speaking populations (Berinsky et al., 2010; Puglisi & Snyder, 2011; Vivyan, Wagner, & Tarlov, 2012) and Western democracies (Cepernich, 2008; Kumlin & Esaiasson, 2012; Maier, 2011), research in other contexts such as this one must continue to help better understand scandals across various political conditions.

Another limitation of the current study stems from the descriptions of the scandalous situations, which may be considered too fake. The descriptions were based on events that have occurred, but prepared in a more general way and so that they would be balanced in the seriousness of the offense. In the future, it may be interesting to assess actual scandals reported in media in aspects of negativity and costs while simultaneously controlling the involved politicians' sex. In the pilot study, sex neutral descriptions were used, albeit even these "no-sex" descriptions could be automatically prescribed to men, as the politician role is more often prescribed to them (Kovacs, 2011; Sanbonmatsu, 2002). Future research should also continue to explore sex as a political variable and how impacts careers, particularly when politicians are involved in scandalous situations, and what resulting consequences may arise.

In the present study, politicians denied involvement in the scandals (as it is typical reaction in Polish political culture), but it would also be recommended to conduct an additional study on the impact of politicians' reaction to the scandal, as Smith et al. (2005) already did. Finally, it should be noted that there are many different types of scandals that can occur, and we by no means were exhaustive in our selections. Sexual and corruptive scandals are not the only kinds of immoral behaviors manifested by politicians, so it is recommended that future research consider alternate forms of misbehavior as well as varying degrees of it.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ariadna Research Panel for support in collecting data and Rachel Calogero for her comments on the early stage of this paper.

References

1. Abele, A., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Communal and agentic content in social cognition: A dual perspective model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 195-255. [ Links ]

2. Basinger, S.J., & Rottinghaus, B. (2012). Skeleton in White House closets: A discussion on modern presidential scandals. Political Science Quarterly, 127, 213-239. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-165X.2012.tb00725.x. [ Links ]

3. Berinsky, A.J., Hutchings, V.L., Mendelberg, T., Shaker, L., & Valentino, N.A. (2010). Sex and race: Are Black candidates more disadvantaged by sex scandals? Political Behavior, 33, 179-202. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9135-8. [ Links ]

4. Bertolotti, M., Catellani, P., Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2013). The "Big Two" in political communication: The effect of attacking and defending politicians' leadership in morality. Social Psychology, 44, 117-128. doi: 10.1027/1864-933 5/a000141. [ Links ]

5. Bhatti, Y., Hansen, K. M., & Olsen, A. L. (2013). Political hypocrisy: The effect of political scandals on candidate evaluations. Acta Politica, DOI: 10.1057/ap.2013.6. [ Links ]

6. Biernat, M. (2003). Toward a broader view of social stereotyping. American Psychologist, 58, 1019-1027. [ Links ]

7. Biernat, M., & Manis, M. (1994) Shifting standards and stereotype-based judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 5-20. [ Links ]

8. Boski, P. (2010). Central-Eastern Europe or Post-Communist Europe? Always behind the West? Presentation on conference: From the totalitarianism toward democracy in Central-Eastern Europe. Warsaw, November 2010. [ Links ]

9. Brambilla, M., Rusconi, P., Sacchi, S., Cherubini, P. (2011). Looking for honesty: The primary role of morality (vs. sociability and competence) in information gathering. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 135-143. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.744. [ Links ]

10. Brooks, D.J. (2014). He runs, she runs: Why gender stereotypes do not harm women candidates. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

11. Burgoon, J. K. (1978). A communication model of personal space violation: Explication and an initial test. Human Connection Research, 4, 129-142. [ Links ]

12. Burgoon, J. K., & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Communication Monographs, 55, 58-79. [ Links ]

13. Cepernich, C. (2008). Landscapes of immorality: Scandals in Italian press (1998-2006). Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 9, 95-109. doi: 10.1080/15705850701825568. [ Links ]

14. Cislak, A., & Wojciszke, B. (2006). The role of self-interest and competence in attitudes toward politicians. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 37, 203-212. [ Links ]

15. Dolan, K. (2014). When does gender matter? Women candidates and gender stereotypes in American elections. Oxford University Press. D0I: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199968275.001.0001. [ Links ]

16. Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

17. Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573-598. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.109.3.573. [ Links ]

18. Fiske, A. P., Haslam, N., & Fiske, S. E. (1991). Confusing one person with another: What errors reveal about the elementary forms of social relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 656-674. [ Links ]

19. Ford, L. E. (2002). Women and politics: The pursuit of equality. Boston, MA, US: Houghton Mifflin Company. [ Links ]

20. Glaser, J., & Salovey, P. (1998). Affect in electoral politics. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 156-172. [ Links ]

21. Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993). Gender stereotypes and the perceptions of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 119-147. [ Links ]

22. Inter-parliamentary Union (2015). Women in national parliaments. Retrieved on 20 January 2015 from www.ipu.org. [ Links ]

23. Johns, R., & Shepard, M. (2007). Gender, candidate image and electoral preference. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 7, 436-438. [ Links ]

24. Johnson, I. (2005). Political trust in societies under transformation. International Journal of Sociology, 35, 63-84. [ Links ]

25. Jussim, L., Coleman, L. M., & Lerch, L. (1987). The nature of stereotypes: A comparison and integration of three theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 536-545. [ Links ]

26. Kahn, K. F. (1992). Does being male help? An investigation of the effects of candidate gender and campaign coverage on evaluations of U.S. Senate candidates. The Journal of Politics, 54, 497-517. [ Links ]

27. Kepplinger, H. M. (2005). Die mechanismen der skandalierung. Die macht der medien und die möglichkeietn der bettroffen (The mechanisms of scandalization in media). Munchen: Olzon Verlag. [ Links ]

28. Kovacs, M. (2011). Political representation and representation of politicians: The "Think politician think male" phenomenon. Paper on Political Psychology Networking Conference for the Post-Communist Region, POLBERG, Budapest, 24-26 November, 2011. [ Links ]

29. Kumlin, S. & Esaiasson, P. (2012). Scandal fatigue? Scandal elections and satisfaction with democracy in Western Europe, 1977-2007. British Journal of Political Science, 42, 263-28. DOI: 10.1017/S000712341100024X. [ Links ]

30. Maier, J. (2011). The impact of political scandals on political support: An experimental test of two theories. International Political Science Review, 32, 283-302. doi: 10.1177/0192512110378056. [ Links ]

31. McGraw, K. M., Timpone, R., & Bruck, G. (1993). Justifying controversial political decisions: Home style in the laboratory. Political Behavior, 15, 289-308. [ Links ]

32. Neckel, S. (2005). Political scandals: an analytic framework. Comparative Sociology, 4(1-2), 101-114. [ Links ]

33. Puchalska, B. (2005). Polish democracy in transition? Political Studies, 53, 816-832. [ Links ]

34. Puglisi, R., & Snyder, J.M. (2011). Newspaper coverage of political scandals. The Journal of Politics, 73, 931-950. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000569. [ Links ]

35. Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 20-34. [ Links ]

36. Sanbonmatsu, K. (2005). Do parties know that women win? Party leader beliefs about women's electability. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association's Annual Meeting, Washington DC, 1-25. [ Links ]

37. Schneider, M.C., & Bos, A. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Political Psychology, 35, 245-266. DOI: 10.1111/pops.12040. [ Links ]

38. Siemieńska, R. (1994). Women in the period of systemic changes in Poland. Journal of Women's History, 5, 70-90. doi: 10.1353/jowh.2010.0283. [ Links ]

39. Smith, E. S., Smith-Powers, A., & Suarez, G. A. (2005). If Bill Clinton were a woman: The effectiveness of male and female politicians' account strategies following alleged transgressions, Political Psychology, 26, 115-134. [ Links ]

40. Stewart, D.D., Rose, R. P., Rosales, F. M., Rudney, P. D., Lehner, T.A., Miltich G., Snyder C., & Sadecki, B. (2013). The value of outside support for male and female politicians involved in a political sex scandal. The Journal of Psychology, 153, 375-394. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2012.744292. [ Links ]

41. Thompson, J. B. (2000). Political scandal: Power and visibility in the media age. Polity Press. [ Links ]

42. Vivyan, N., Wagner, M., & Tarlov, J. (2012). Representative misconduct, voter perceptions and accountability: evidence from the 2009 House of Commons expenses scandal. Electoral Studies, 31, 750-763. [ Links ]

43. Wattenberg, M. (1991). The rise of candidate-centered politics: Presidential elections of the 1980s. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

44. Wiliams, J. E., & Best, D. L. (1990). Sex and psyche: Gender and self viewed cross-culturally. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

45. Wiid, R., Pitt, L.E., & Engstrom, A. (2011). Not so sexy: public opinion of political sex scandals as reflected in political cartoons. Journal of Public Affairs, 11, 137-147. doi: 10.1002/pa.401. [ Links ]

46. Wojciszke, B., & Klusek, B. (1996). Moral and competence-related traits in political perception. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 27, 319-325. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Magdalena A. Żemojtel-Piotrowska.

Gdansk University,

Institute of Psychology,

Bazynskiego 4 Street, 80-952

Gdansk (Poland).

E-mail: psymzp@ug.edu.pl

Article received: 06-06-2015

revised: 01-02-2016

accepted: 04-02-2016